Leray J. Lagrangian Analysis and Quantum Mechanics: A Mathematical Structure Related to Asymptotic Expansions and the Maslov Index

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Lagrangian Analysis and Quantum Mechanics

A Mathematical Structure Related to

Asymptotic Expansions and the Maslov Index

Jean Leray

English translation by Carolyn Schroeder

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

Copyright C) 1981 by The Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means,

elcctronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information

storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in Monophoto Times Roman by Asco Trade Typesetting Ltd.,

Hong Kong, and printed and bound by Murray Printing Company in the United States

of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging In Publication Data

Leray, Jean, 1906-

Lagrangian analysis and quantum mechanics.

Bibliography: p.

Includes indexes.

1. Differential equations, Partial-Asymptotic theory. 2. Lagrangian functions.

3. Maslov index. 4. Quantum theory. I. Title.

QA377.L4141982 515.3'53

81-18581

ISBN 0-262-12087-9

AACR2

To Hans Lewy

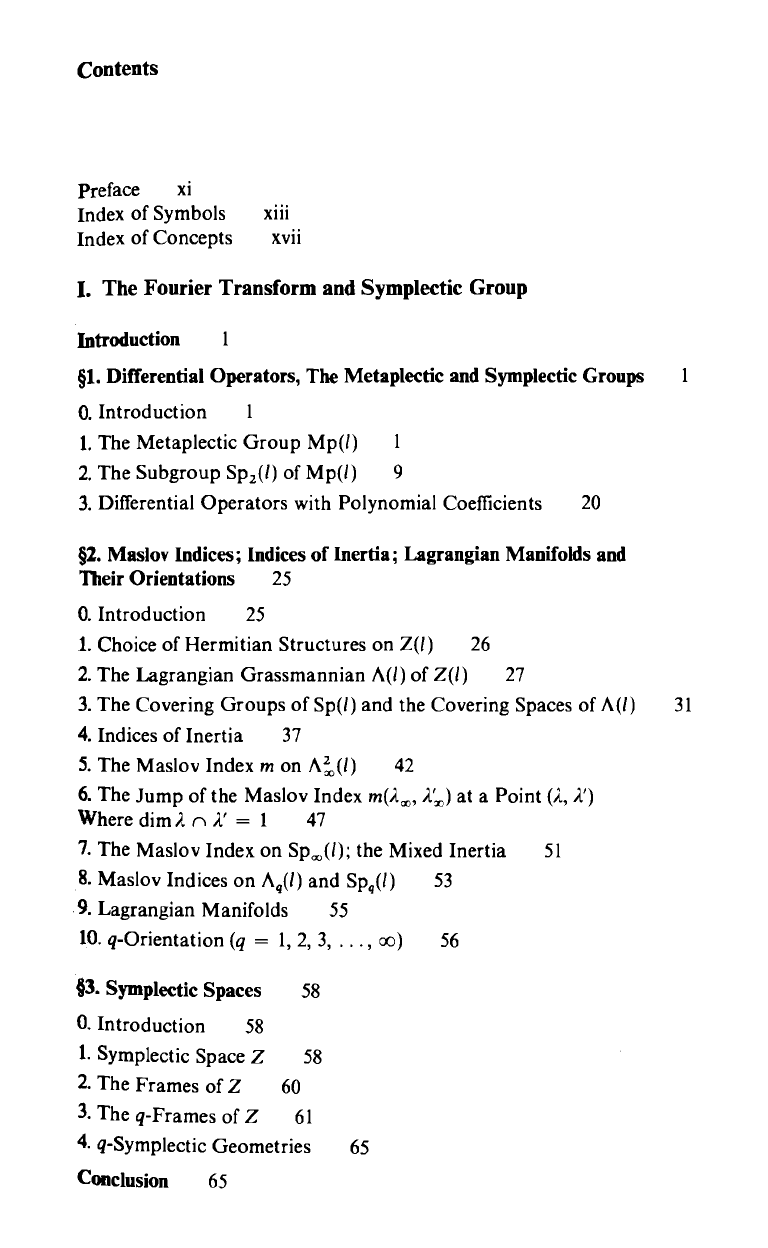

Contents

Preface

xi

Index of Symbols

xiii

Index of Concepts

xvii

I. The Fourier Transform and Symplectic Group

Introduction

1

§1. Differential Operators, The Metaplectic and Symplectic Groups

1

0. Introduction

1

1. The Metaplectic Group Mp(l)

1

2. The Subgroup Spz(l) of MP(l)

9

3. Differential Operators with Polynomial Coefficients

20

§2. Maslov Indices; Indices of Inertia; Lagrangian Manifolds and

Their Orientations

25

0. Introduction 25

1. Choice of Hermitian Structures on Z(1)

26

2. The Lagrangian Grassmannian A(l) of Z(1) 27

3. The Covering Groups of Sp(l) and the Covering Spaces of A(l)

31

4. Indices of Inertia

37

5. The Maslov Index m on A2 (1)

42

6. The Jump of the Maslov Index m(A., A..) at a Point (ti, A.')

Where dim;, n A.' = 1

47

7. The Maslov Index on Spa (l); the Mixed Inertia

51

8. Maslov Indices on A,(/) and Sp,,(/)

53

9. Lagrangian Manifolds

10. q-Orientation (q

= 1, 2,

55

3,

...,

cc)

56

§3. Symplectic Spaces

58

0. Introduction

58

1. Symplectic Space Z

58

2. The Frames of Z

60

3. The q-Frames of Z

61

4. q-Symplectic Geometries

65

Conclusion

65

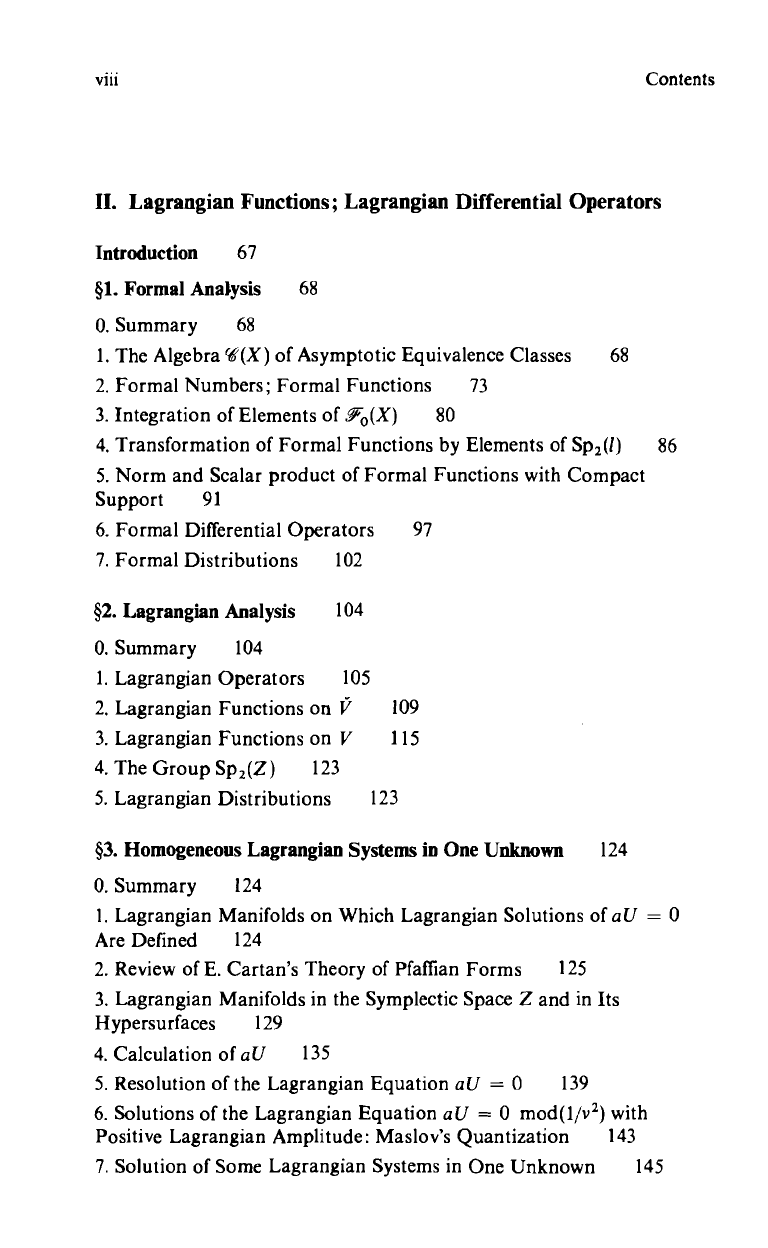

viii

Contents

II. Lagrangian Functions; Lagrangian Differential Operators

Introduction 67

§1. Formal Analysis

68

0. Summary

68

1. The Algebra W(X) of Asymptotic Equivalence Classes

68

2. Formal Numbers; Formal Functions

73

3. Integration of Elements of .FO(X)

80

4. Transformation of Formal Functions by Elements of Sp2(l)

86

5. Norm and Scalar product of Formal Functions with Compact

Support 91

6. Formal Differential Operators

97

7. Formal Distributions 102

§2. Lagrangian Analysis

104

0. Summary

104

1. Lagrangian Operators

105

2. Lagrangian Functions on V

109

3. Lagrangian Functions on V

115

4. The Group Sp2(Z)

123

5. Lagrangian Distributions

123

§3. Homogeneous Lagrangian Systems in One Unknown 124

0. Summary

124

1. Lagrangian Manifolds on Which Lagrangian Solutions of aU = 0

Are Defined

124

2. Review of E. Cartan's Theory of Pfaffian Forms

125

3. Lagrangian Manifolds in the Symplectic Space Z and in Its

Hypersurfaces

129

4. Calculation of aU

135

5. Resolution of the Lagrangian Equation aU = 0

139

6. Solutions of the Lagrangian Equation aU = 0 mod(1/v2) with

Positive Lagrangian Amplitude: Maslov's Quantization

143

7. Solution of Some Lagrangian Systems in One Unknown 145

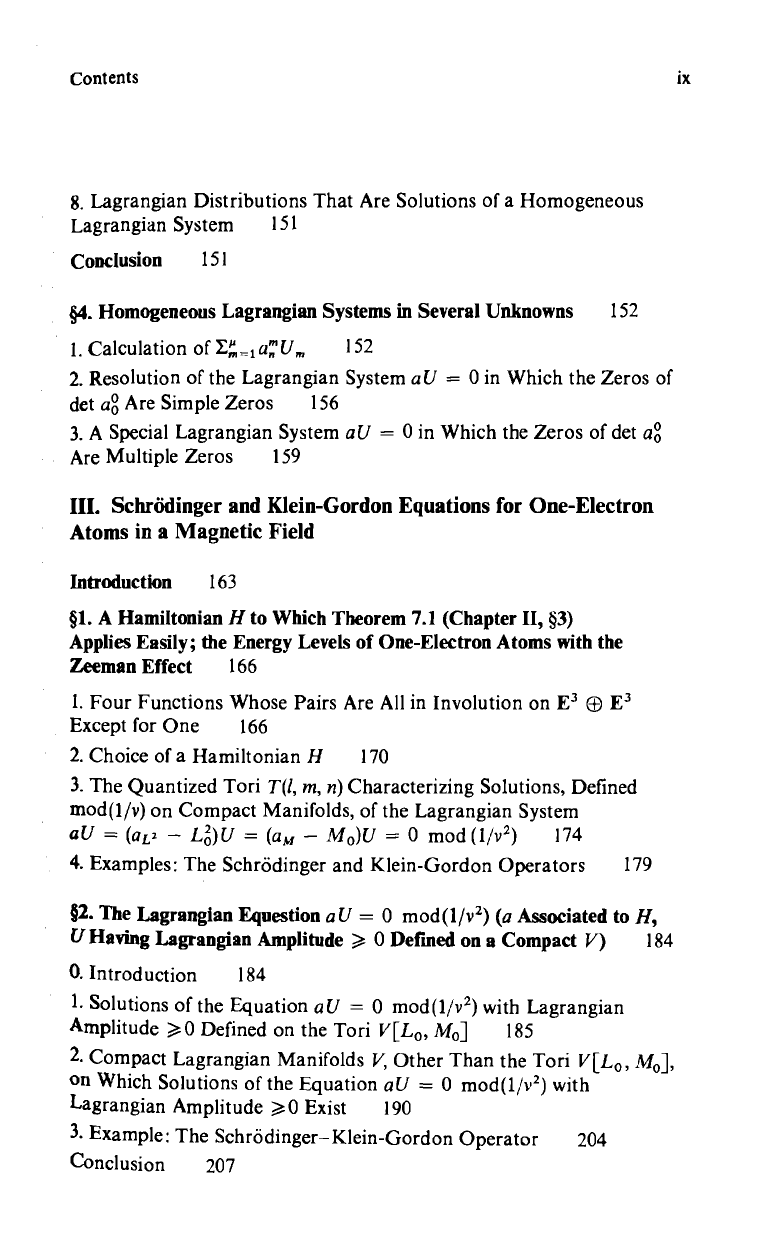

Contents

ix

8. Lagrangian Distributions That Are Solutions of a Homogeneous

Lagrangian System

151

Conclusion

151

§4. Homogeneous Lagrangian Systems in Several Unknowns

152

1. Calculation of Em_a' U,,

152

2. Resolution of the Lagrangian System aU = 0 in Which the Zeros of

det ao Are Simple Zeros

156

3. A Special Lagrangian System aU = 0 in Which the Zeros of det ao

Are Multiple Zeros

159

III. Schrodinger and Klein-Gordon Equations for One-Electron

Atoms in a Magnetic Field

Introduction

163

§1. A Hamiltonian H to Which Theorem 7.1 (Chapter II, §3)

Applies Easily; the Energy Levels of One-Electron Atoms with the

Zeeman Effect

166

1. Four Functions Whose Pairs Are All in Involution on E3 Q+ E3

Except for One

166

2. Choice of a Hamiltonian H

170

3. The Quantized Tori T(l, m, n) Characterizing Solutions, Defined

mod(1/v) on Compact Manifolds, of the Lagrangian System

aU = (aL2 - L2)U = (am - Mo)U = 0 mod (1/v2) 174

4. Examples: The Schrodinger and Klein-Gordon Operators

179

§2. The Lagrangian Equestion aU

= 0 mod(1/v2) (a Associated to H,

U Having Lagrangian Amplitude >, 0 Defined

on a Compact V) 184

0. Introduction

184

1. Solutions of the Equation aU

= 0 mod(1/v2) with Lagrangian

Amplitude >,0 Defined on the Tori V[L0, M0]

185

2. Compact Lagrangian Manifolds V, Other Than the Tori V[L0,

M0],

on Which Solutions of the Equation aU

= 0 mod(1/v2) with

Lagrangian Amplitude

30 Exist

190

3. Example: The Schrodinger-Klein-Gordon

Operator

204

Conclusion

207

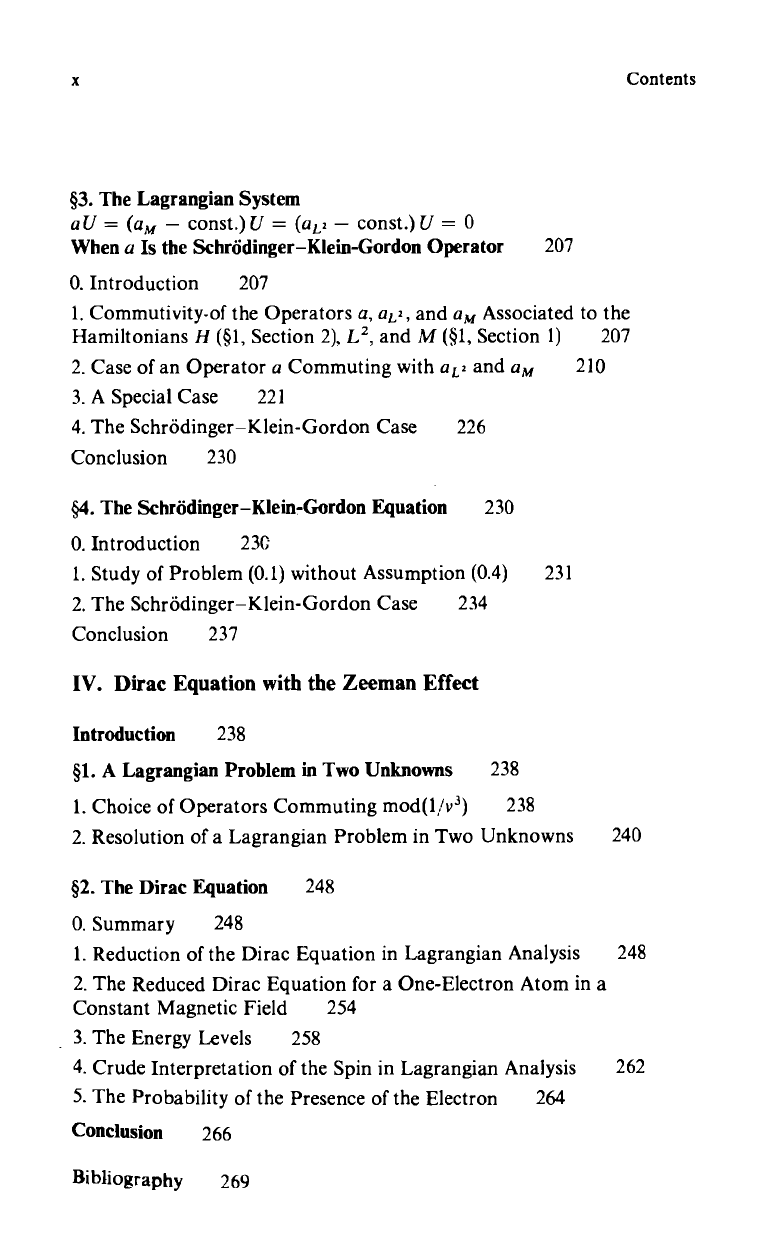

x

Contents

§3. The Lagrangian System

a U = (am - const.) U = (aL2 - const.) U = 0

When a Is the Schrodinger-Klein-Gordon Operator

207

0. Introduction 207

1. Commutivity-of the Operators a, aL=, and am Associated to the

Hamiltonians H (§1, Section 2), L2, and M (§1, Section 1)

2. Case of an Operator a Commuting with

aL2

and am

207

210

3. A Special Case

221

4. The Schrodinger-Klein-Gordon Case 226

Conclusion

230

§4. The Schrodinger-Klein-Gordon Equation

230

0. Introduction

230

1. Study of Problem (0.1) without Assumption (0.4)

231

2. The Schrodinger-Klein-Gordon Case

234

Conclusion

237

IV. Dirac Equation with the Zeeman Effect

Introduction

238

§1. A Lagrangian Problem in Two Unknowns

238

1. Choice of Operators Commuting mod(1!v3)

238

2. Resolution of a Lagrangian Problem in Two Unknowns

240

§2. The Dirac Equation

248

0. Summary

248

1. Reduction of the Dirac Equation in Lagrangian Analysis

248

2. The Reduced Dirac Equation for a One-Electron Atom in a

Constant Magnetic Field

254

3. The Energy Levels

258

4. Crude Interpretation of the Spin in Lagrangian Analysis

262

5. The Probability of the Presence of the Electron

264

Conclusion

266

Bibliography

269

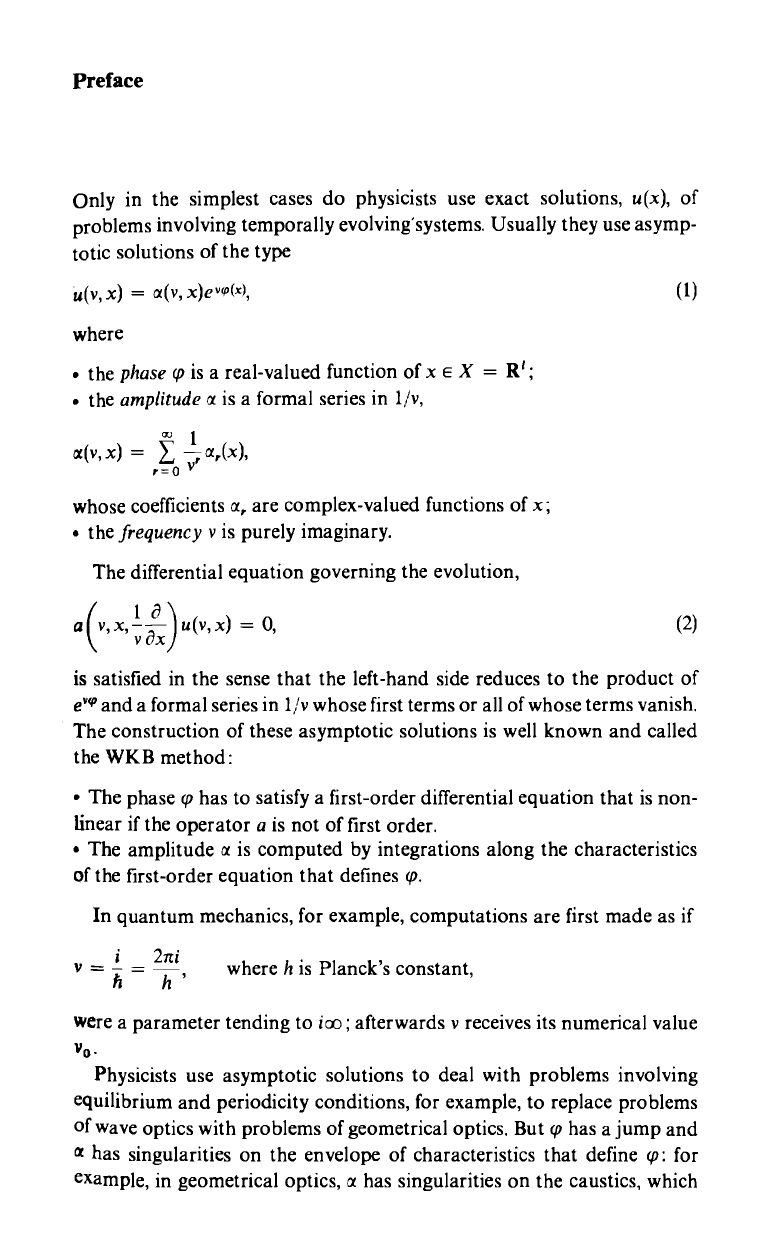

Preface

Only in the simplest cases do physicists use exact solutions, u(x), of

problems involving temporally evolving'systems. Usually they use asymp-

totic solutions of the type

u(v, x) = a(v, x)evw(x),

where

the phase (p is a real-valued function of x E X = R';

the amplitude a is a formal series in 1/v,

w 1

a(v, x)

=a V

whose coefficients a, are complex-valued functions of x;

the frequency v is purely imaginary.

The differential equation governing the evolution,

a(v,x 1 a lu(v,x)

= 0,

vaxf)

(1)

(2)

is satisfied in the sense that the left-hand side reduces to the product of

e'V and a formal series in l /v whose first terms or all of whose terms vanish.

The construction of these asymptotic solutions is well known and called

the WKB method:

The phase q has to satisfy a first-order differential equation that is non-

linear if the operator a is not of first order.

The amplitude a is computed by integrations along the characteristics

of the first-order equation that defines cp.

In quantum mechanics, for example, computations are first made as if

where h is Planck's constant,

were a parameter tending to ioo; afterwards v receives its numerical value

vv.

Physicists use asymptotic solutions to deal with problems involving

equilibrium and periodicity conditions, for example, to replace problems

of wave optics with problems of geometrical optics. But cp has a jump and

a has singularities on the envelope of characteristics that define cp: for

example, in geometrical optics, a has singularities on the caustics, which