Lefebvre A.H., Ballal D.R. Gas Turbine Combustion: Alternative Fuels and Emissions

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

240 Gas Turbine Combustion: Alternative Fuels and Emissions, Third Edition

secondary orice or the secondary spray within the orice. When the fuel

delivery is low, it all ows through the primary nozzle, and atomization qual-

ity tends to be high because a fairly high fuel pressure is needed to force the

fuel through the small ports in the primary swirl chamber. As the fuel sup-

ply is increased, a fuel pressure is eventually reached at which a valve opens

and admits fuel to the secondary nozzle. At this point, atomization quality

is poor because the secondary fuel pressure is low. With further increases

in fuel ow, the secondary fuel pressure increases, and atomization quality

starts to improve. However, there is an inevitable range of fuel ows, starting

from the point at which the valve opens, over which drop sizes are relatively

large. To alleviate this problem, it is customary to arrange for the primary

spray cone angle to be slightly wider than the secondary spray cone angle, so

that the two sprays coalesce and share their energy within a short distance

from the atomizer.

6.7.4 Spill return

This is basically a simplex atomizer, except that the rear wall of the swirl

chamber, instead of being solid, contains a passage through which the

fuel that is surplus to combustion requirements enters the spill line and is

returned to the fuel tank, as shown in Figure 6.13d. The main attraction of this

system is that the fuel-injection pressure is always high, even at the lowest

fuel ow rate, thus atomization quality is always excellent. Other attractive

features include an absence of moving parts and, because the ow passages

are designed to handle large ows all the time, freedom from “plugging” by

contaminants in the fuel. The principal drawbacks of the spill-return atom-

izer are high fuel-pump power requirements and a wide variation in spray

cone angle with change in fuel ow rate.

Another disadvantage of the spill system is that problems of metering

the ow rate are more complicated than with other types of atomizer, and

a larger-capacity pump is needed to handle the large recirculating ows.

For these reasons, interest in the spill-return atomizer for gas turbines has

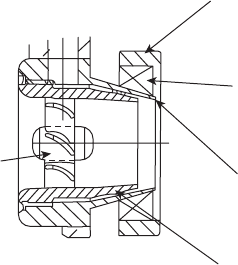

Secondar

y

Primary

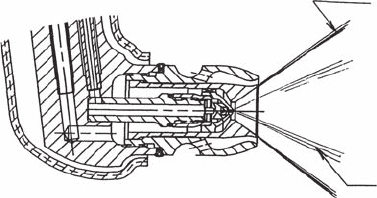

Figure 6.14

Dual-orice atomizer. (Courtesy of Parker Hannin Corporation.)

Fuel Injection 241

gradually declined, and for the past several decades its main application has

been to large industrial furnaces. However, if the aromatic content of gas

turbine fuels continues to rise, it could pose serious problems of blockage

by gum formation of the small passages of conventional pressure atomizers.

The spill-return atomizer, having no small passages, is virtually free from

this defect. Furthermore, by the judicious application of swirling air ow-

ing around the nozzle, it is possible to maintain a fairly constant spray cone

angle regardless of changes in fuel ow rate.

6.8 Rotary Atomizers

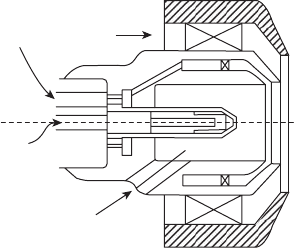

By far, the best known rotary atomizer is the “slinger” system, which was

developed by the Turbomeca company in France. It is used in conjunction

with a radial-annular combustion chamber, as illustrated in Figure 6.15. Fuel

is supplied at low pressure along the hollow main shaft and is discharged

radially outward through holes drilled in the shaft. These injection holes

vary in number from 9 to 18 and in diameter from 2.0 to 3.2 mm. The holes

may be drilled in the same plane as a single row, but some installations fea-

ture a double row of holes. The holes never run full; they have a capacity

that is many times greater than the required ow rate. They are made large

to obviate blockage. However, it is important that the holes be accurately

machined and nished because experience has shown that uniformity of

ow between one injection hole and another depends very much on their

dimensional accuracy and surface nish. Clearly, if one injection hole sup-

plies more fuel than the others, it will produce a rotating “hot spot” in the

exhaust gases, with disastrous consequences for the particular turbine blade

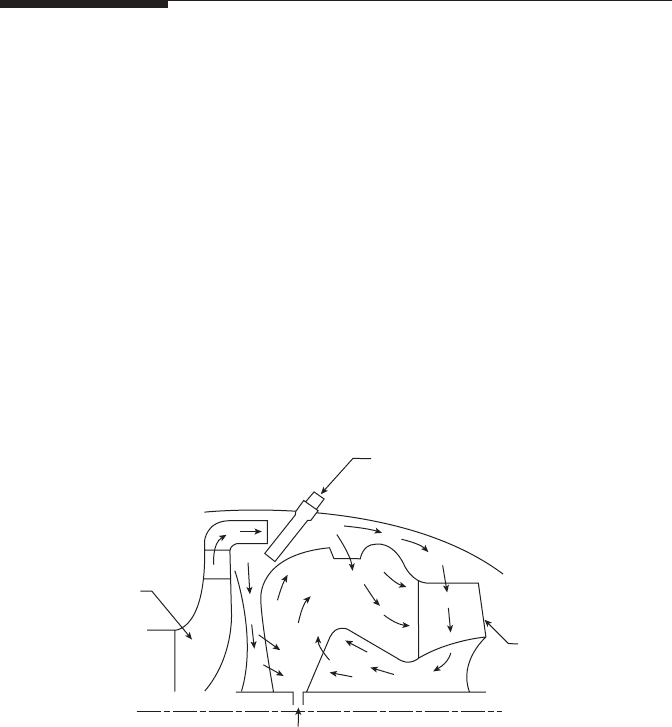

Fuel inlet

Hollow nozzle

guide vanes

Igniter

Compressor

Figure 6.15

Turbomeca slinger system.

242 Gas Turbine Combustion: Alternative Fuels and Emissions, Third Edition

on which the hot spot happens to impinge. Flow uniformity is also critically

dependent on the ow path provided for the fuel inside the shaft, espe-

cially in the region near the holes. Where there are two rows of holes, it is

very important to achieve the correct ow division between the two rows.

The internal geometry of the shaft is important in this regard.

The main advantages of the slinger system are its cheapness and simplic-

ity. Only a low-pressure fuel pump is needed, and the quality of atomization

is always satisfactory, even at speeds as low as 10% of the rated maximum.

The inuence of fuel viscosity is small, so the system has a potential multi-

fuel capability.

The main problems with the system appear to be those of igniter-plug loca-

tion, poor high-altitude relighting performance and, because of the long ow

path, slow response to changes in fuel ow. Wall cooling could also pose a

major problem if the system were applied to engines of high pressure ratio.

The system seems ideally suited for small engines of low compression

ratio, and this has been its main application to date. As the success of the

system depends on high rotational speeds, usually greater than 350 rps, it is

clearly less suitable for large engines where shaft speeds are much lower. In

the United States, slinger-type systems have been used successfully on sev-

eral engines produced by the Williams Research Corporation.

6.9 Air-Assist Atomizers

As discussed earlier, a basic drawback of the simplex nozzle is that if the

swirl ports are sized to pass the maximum fuel ow at the maximum fuel-

injection pressure, then the fuel pressure differential will be too low to give

good atomization at the lowest fuel ow condition. This problem can be

overcome by sizing the fuel ports for the highest fuel ow rate and then

using high-velocity air to augment the atomization process at low fuel ows.

A wide variety of designs of this type have been produced for use in indus-

trial gas turbines. Useful descriptions of these may be found in Mullinger

and Chigier [28].

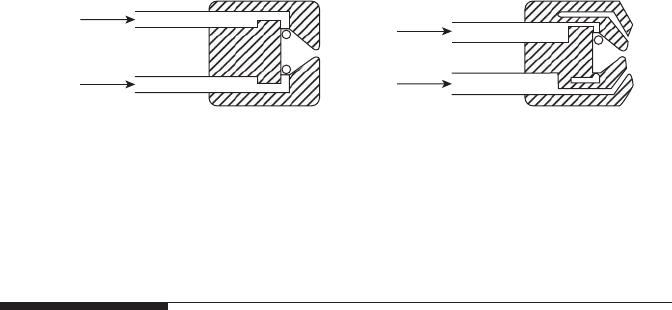

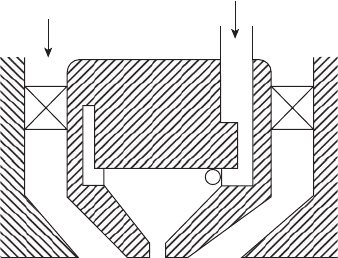

In the internal-mixing conguration, shown schematically in Figure 6.16a,

air and fuel mix within the nozzle before exiting through the outlet ori-

ce. The fuel is sometimes supplied through tangential slots to encourage a

conical spray pattern. However, the maximum spray angle is usually about

60°. As its name suggests, in the external-mixing form of the air-assist noz-

zle, the high-velocity air impinges on the fuel downstream of the discharge

orice, as illustrated in Figure 6.16b. Its advantage over the internal-mixing

type is that problems of back pressure are avoided because there is no inter-

nal communication between air and fuel. However, it is less efcient than the

internal-mixing concept, and higher airow rates are needed to achieve the

Fuel Injection 243

same degree of atomization. Both types of nozzles can effectively atomize

high-viscosity liquids.

6.10 Airblast Atomizers

In principle, the airblast atomizer functions in exactly the same manner as

the air-assist atomizer because both employ the kinetic energy of a owing

airstream to shatter the fuel jet or sheet into ligaments and then drops. The

main difference between the two systems lies in the quantity of air employed

and its atomizing velocity. With the air-assist nozzle, where the air is supplied

from a compressor or a high-pressure cylinder, it is important to keep the air-

ow rate down to a minimum. However, as there is no special restriction on

air pressure, the atomizing air velocity can be made very high. Thus, air-assist

atomizers are characterized by their use of a relatively small quantity of very

high-velocity air. However, because the air velocity through an airblast atom-

izer is limited to a maximum value (usually around 120 m/s), corresponding

to the pressure differential across the combustor liner, a larger amount of air is

required to achieve good atomization. However, this air is not wasted because

after atomizing the fuel, it conveys the drops into the combustion zone, where

it meets and mixes with the additional air employed in combustion.

Airblast atomizers have many advantages over pressure atomizers,

especially in their application to combustion systems operating at high

pressures. They require lower fuel-pump pressures and produce a ner

spray. Moreover, because the airblast atomization process ensures thorough

mixing of air and fuel, the ensuing combustion process is characterized by

very low soot formation and a blue ame of low luminosity, resulting in

relatively low ame radiation and a minimum of exhaust smoke. The merits

of the airblast atomizer have led to its installation in a wide range of aircraft,

marine, and industrial gas turbines.

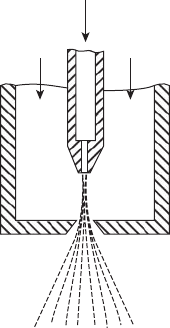

6.10.1 Plain-Jet Airblast

This is perhaps the simplest form of airblast atomizer, as illustrated in

Figure 6.17. It features a round jet of fuel that is injected along the axis of

(a) (b)

Fuel

Air

Fuel

Air

Figure 6.16

Schematic drawings of air-assist atomizers: (a) internal mixing; (b) external mixing.

244 Gas Turbine Combustion: Alternative Fuels and Emissions, Third Edition

a generally co-owing round jet of air. Although this type of atomizer has

relatively few applications in gas turbine combustion, it has some practical

signicance because much of our present knowledge on the effects of air

and fuel properties on the mean drop sizes produced in airblast atomization

was obtained with this type of atomizer, including the pioneering study of

Nukiyama and Tanasawa [29].

6.10.2 Prefilming Airblast

Most of the airblast atomizers now in service are of the prelming type, in

which the fuel is rst spread out into a thin continuous sheet and then sub-

jected to the atomizing action of high-velocity air. One example of a pre-

lming airblast atomizer designed for gas turbines is shown in Figure 6.18.

In this design, the atomizing air ows through two concentric air passages

that generate two separate swirling airows at the nozzle exit. The fuel ows

through a number of equispaced tangential ports onto a prelming surface

where it spreads into a thin, circumferentially uniform sheet before being

discharged at the atomizing “lip” or “edge” into the interface between the

two swirling airstreams. The amount of air employed in atomization is

constrained by the need to restrict atomizer size, partly in order to reduce

weight, but also to avoid weakening the combustor casing by large insertion

holes. Thus, modern prelming airblast atomizers normally operate with a

maximum air/fuel ratio (AFR) of around 3.

An important design choice is whether the two swirling airstreams should

be co-rotating or counter-rotating. The advantage of co-rotation is that the

two airstreams support each other in helping to create a strong primary-zone

Liquid

Air Air

Figure 6.17

Plain-jet airblast atomizer.

Fuel Injection 245

ow recirculation. The advantage of counter-rotation is that it promotes a

shearing action between the fuel and the atomizing air, which is benecial to

both atomization and fuel–air mixing. However, because the two swirl com-

ponents are in opposite directions, the resulting swirl strength may be so

small that the atomizing air does little to promote primary-zone ow recir-

culation. This drawback can be alleviated by making one airstream, usually

the outer, much stronger than the other.

Chin et al. [30] carried out an experimental study using a prelming injec-

tor that had the capability of reversing the direction of rotation of each of the

two air swirlers used in the design. The results demonstrated that a combi-

nation of co-rotating inner airstream and counter-rotating outer airstream

with respect to the rotational direction of the liquid lm, yields the lowest

SMD, as compared with other swirler congurations. The worst atomization

was achieved when both airstreams were swirling in opposite directions to

that of the liquid lm.

6.10.3 Piloted Airblast

This device is also known as a “hybrid” injector because it consists of a

prelming airblast atomizer with a simplex pressure-swirl nozzle located

on its centerline, as shown in Figure 6.19. The design objective is to over-

come the airblast atomizer’s inherent drawbacks of poor lean blowout

performance (see Chapter 5) and poor atomization during engine startup

when atomizing air velocities are low. At low fuel ows, all fuel is supplied

through the pilot nozzle, and a well-atomized spray is obtained, giving ef-

cient combustion at startup and idling. On aero engines, it also ensures

good high-altitude relight performance. At higher power settings, fuel is

supplied to both the airblast and pilot nozzles. The relative amounts are

Inner air swirler

Shroud

Outer air swirler

Fuel pre-filmer

Fuel swirler

Figure 6.18

Basic components of prelming airblast atomizer. (Courtesy of Parker Hannin Corporation.)

246 Gas Turbine Combustion: Alternative Fuels and Emissions, Third Edition

such that at the highest fuel ow conditions most of the fuel is supplied to

the airblast atomizer. By this means, the performance requirements of good

atomization at low fuel ows and low exhaust smoke at high fuel ows are

both realized.

Chin et al. have carried out a number of experimental and modeling stud-

ies on the performance of hybrid atomizers (see, e.g., References [31] and

[32]). These studies have focused on the interaction between the two separate

sprays and on the inuence of various atomizer design features on drop-size

distributions in the combined spray. The results obtained provide detailed

information for the modeling of combustors featuring hybrid atomizers and

also on the methods available to the designer for optimizing atomization

performance at various key combustor operating conditions.

6.10.4 Airblast Simplex

In its simplest form, the airblast simplex (ABS) atomizer comprises a simplex

pressure-swirl nozzle surrounded by a co-owing stream of swirling air.

Essentially, it is the same as an external-mixing air-assist atomizer; the only

difference is that atomizing air is supplied continuously and not just as and

when required. It also has much in common with the hybrid airblast atom-

izer, except that in the latter the pressure-swirl nozzle supplies only a small

fraction of the fuel at high-power conditions, whereas with the ABS concept

the pressure-swirl nozzle supplies all the fuel at all conditions. According to

Benjamin et al. [33], ABS atomizers offer the following advantages for aero-

engine applications:

1. They are easier and cheaper to manufacture than prelming airblast

atomizers.

2. The heat shielding required to inhibit fuel coking is simpler to design

and implement for the fuel passages of ABS atomizers than for the

Main fuel

Air

Air

Pilot fuel

Figure 6.19

Piloted airblast atomizer. (From Rizk, N.K., Chin, J.S., and Razdan, M.K., AIAA Paper 96-2628,

1996. With permission.)

Fuel Injection 247

small gaps between the inner and outer swirlers of prelming air-

blast atomizers.

3. A simplex nozzle has a higher altitude relight capability than a pre-

lming airblast atomizer for a given fuel pressure drop.

The main barrier to the practical implementation of ABS nozzles has been

that simplex atomizer sprays are known to “collapse” at elevated ambient

pressures. This drawback would appear to rule them out for application to

modern high-performance engines. However, Benjamin et al. have shown

that spray collapse is not signicant if the mass ratio of atomizing air to fuel

is maintained above about 3.

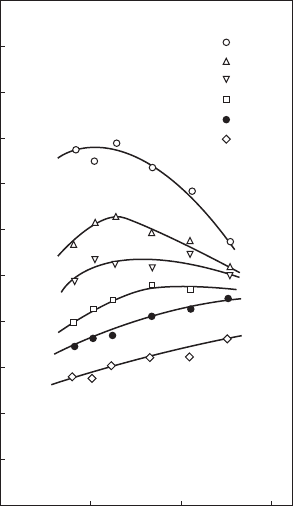

Suyari and Lefebvre [34] investigated the atomizing performance of an

ABS nozzle of the type shown in Figure 6.20. Measurements of SMD were

carried out using water, gasoline, kerosine, and diesel oil. Some of the results

obtained for kerosine are shown in Figure 6.21. From these and other data,

they drew the following conclusions:

1. The key factors governing atomization quality are the dynamic pres-

sure of the atomizing air and the relative velocity between the fuel

and the surrounding air.

2. For any given value of air velocity, a continual increase in fuel ow

rate from an initial value of zero produces an increase in SMD up to

a maximum value, beyond which further increases in fuel ow rate

causes SMD to decline.

3. The fuel ow rate at which the SMD attains its maximum value

increases with an increase in atomizing air velocity.

Air

Liquid

Figure 6.20

Schematic drawing of airblast simplex nozzle.

248 Gas Turbine Combustion: Alternative Fuels and Emissions, Third Edition

4. Whereas an increase in air velocity is usually benecial to atomiza-

tion quality, an increase in fuel velocity may help or hinder atomi-

zation, depending on whether it increases or decreases the relative

velocity between the fuel and the surrounding air.

In a more recent study, Maier et al. [35] also observed that for any given value

of air velocity, an increase in liquid ow rate initially increases the SMD up

to a maximum, followed by a continuous reduction in droplet size. Also in

agreement with Suyari and Lefebvre, they found that with increasing air

velocity, the maximum SMD moves to higher liquid ow rates, accompanied

by a simultaneous reduction of the maximum value.

A most useful outcome of this research was the nding that substantial

differences in atomization quality can be obtained depending on the relative

swirl orientations of the airow and the liquid sheet. For counter-rotating

swirls, the peaks in the SMD curves are identied as a collapse of the tulip

0

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Air-assist atomizer

P

A

= 101 kPa

Liquid = kerosine (JP-5)

∆P

A

/P

A

, %

110

SMD, µm

0.0025 0.0050

m

.

L

, kg/s

0.0075

1

2

3

4.22

5.77

7.9

Figure 6.21

Inuence of liquid ow rate and atomizing air velocity on mean drop size. (From Suyari, M.

and Lefebvre, A.H., Paper presented at Central States Combustion Institute Spring Meeting,

NASA-Lewis Research Center, Cleveland, OH, 1986. With permission.)

Fuel Injection 249

shape of the liquid sheet into the onion shape. For co-rotating swirls, the

tendency to collapse is much smaller [35].

6.11 Effervescent Atomizers

All the twin-uid atomizers described above, in which air is used either to

augment atomization or as the primary driving force for atomization, have

one important feature in common: the bulk liquid to be atomized is rst

transformed into a jet or sheet before being exposed to high-velocity air. An

alternative approach is to introduce the air directly into the bulk liquid at

some point upstream of the nozzle discharge orice. This air is injected at

low velocity and forms bubbles that produce a two-phase bubbly ow at the

discharge orice. When the air bubbles emerge from the nozzle, they expand

so rapidly that the surrounding liquid is shattered into droplets.

The advantages offered by effervescent atomization in gas turbine applica-

tions include the following:

1. Atomization is very good even at very low injection pressures and

low airow rates. When operating at a typical AFR of 0.03, mean

drop sizes are comparable to those obtained with airblast atomizers

at an AFR of 3.0.

2. The system has large holes and passages so that problems of “plug-

ging” are greatly reduced. This could be an important advantage

for combustion systems that burn residual fuels, slurry fuels, or any

other type of fuel where atomization is impeded by the necessity of

using large hole and passage sizes to avoid plugging of the nozzle.

3. The aeration of the spray created by the presence of the air bubbles could

prove benecial in alleviating soot formation and exhaust smoke.

4. The basic simplicity of the device lends itself to good reliability, easy

maintenance, and low cost.

One drawback to effervescent atomization is that the resulting spray is char-

acterized by a wide distribution of drop sizes, which typically correspond to

a Rosin–Rammler distribution parameter q of about 2. A more serious draw-

back, however, is the need for a separate supply of atomizing air, which must

be provided at essentially the same pressure as that of the fuel. Although this

air requirement is small, about 1% by mass of what is required by a prelm-

ing airblast atomizer, it necessitates a separate compressor. This drawback

would appear to rule it out for aircraft applications, but it should not be a

serious impediment to its installation in automotive, marine, and industrial

gas turbines.