Kuppan T. Heat Exchanger Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

I34

Chapter

3

Enhanced version of TEMA specification sheet

Condensing details

Vaporization details

Warning and messages on any design, fabrication, or operation considerations or problems

3.2

Thermal Design Program-AEROTRAN

The salient features of the AEROTRAN program for the thermal design

of

air coolers are

given in Tables

3

and

4.

4

HEAT EXCHANGER DESIGN PROBLEMS

In

a broad sense, the design

of

a new heat exchanger means the selection of exchanger con-

struction type, flow arrangement, tube and fin material, and the physical size

of

an exchanger

to meet the specified heat-transfer and pressure-drop requirements. Two most common heat

exchanger design problems are the rating and sizing. For an existing exchanger, the perfor-

mance evaluation problem is referred to as the rating problem. The sizing problem is

also

referred to as the design problem. Rating and sizing problems are discussed here. For more

details on the rating and sizing problems, refer to Refs.

2

and

5

and Bell

[6].

4.1 Rating

Determination of heat-transfer and pressure-drop performance of either an existing exchanger

or an already sized exchanger is referred to as a rating problem. Inputs to the rating problem

include

[

11: (1) heat exchanger construction details,

(2)

flow arrangement,

(3)

overall dimen-

sions,

(4)

material details,

(5)

surface geometries and surface characteristics

(j

and

f

factors),

(6)

fluid flow rates,

(7)

inlet temperatures, and

(8)

fouling factors. The designers’s task

is

to

predict the fluid outlet temperatures, total heat-transfer rate, and pressure drop on each side.

Rating of a Compact Exchanger

The rating problems for a two-fluid direct-transfer type compact heat exchanger that has gas

as a worlung fluid at least on one side is discussed briefly here, and the detailed rating of a

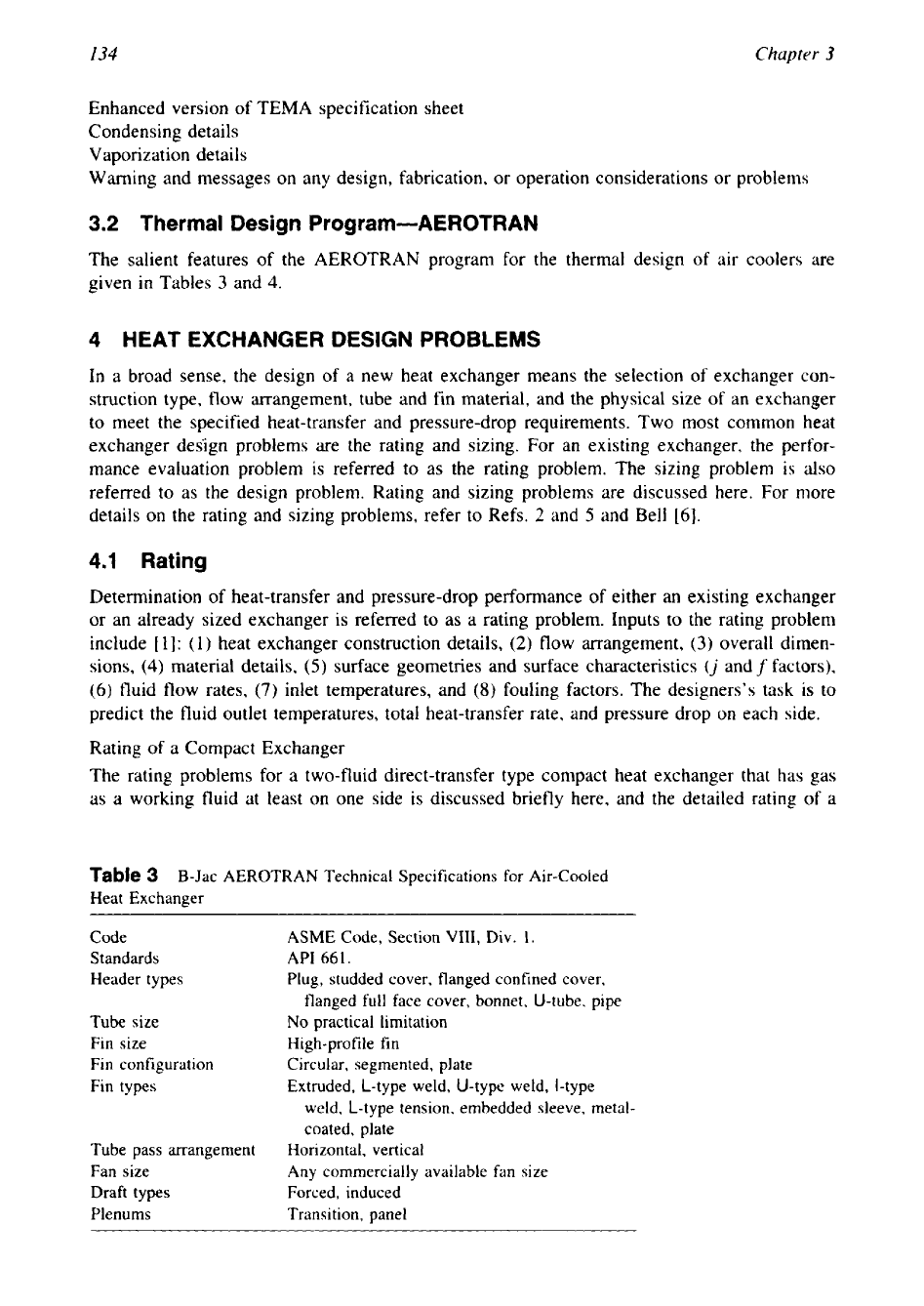

Table

3

B-Jac AEROTRAN Technical Specifications for Air-cooled

Heat Exchanger

Code ASME Code, Section

VIII,

Div.

1.

Standards

API

66

1.

Header types

Plug, studded cover, flanged confined cover,

flanged full face cover, bonnet, U-tube, pipe

Tube size

No practical limitation

Fin size

High-profile fin

Fin configuration

Circular, segmented, plate

Fin types

Extruded, L-type weld, U-type weld, I-type

weld, L-type tension, embedded sleeve, metal-

coated, plate

Tube pass arrangement

Horizontal, vertical

Fan size

Any

commercially available fan size

Draft types

Forced, induced

Plenums

Transition, panel

--

Heat Exchanger Thermal Design

I35

Table

4

B-Jac AEROTRAN Output

Optimization path

Design summary

Performance evaluation

Heat-transfer coefficients

MTDLMTD, heat flux

Pressure drop

Construction

of

bundle

Fan details

Heat exchanger specification sheet

Recap

of

designs

Condensing details

Warnings and messages

crossflow and counter-crossflow exchanger is described separately. Customarily, the E-NTU

method is employed for compact heat exchangers. Hence, the solution procedure is outlined

here using the E-NTU method. The basic steps involved in the analysis of a rating problem are

the determination of:

1.

Surface geometrical parameters

2.

Thermophysical fluid properties

3.

Reynolds numbers

4.

Surface characteristics,

j

and

f

5.

Corrections to the temperature-dependent fluid properties

6.

Heat-transfer coefficients

7.

Fin

effectiveness and overall surface effectiveness

8.

Thermal resistance due to conduction wall

9.

Overall heat-transfer coefficient

10.

NTU,

C*,

and exchanger effectiveness

E

11.

Heat transfer rate, outlet temperatures, and pressure drop on each side

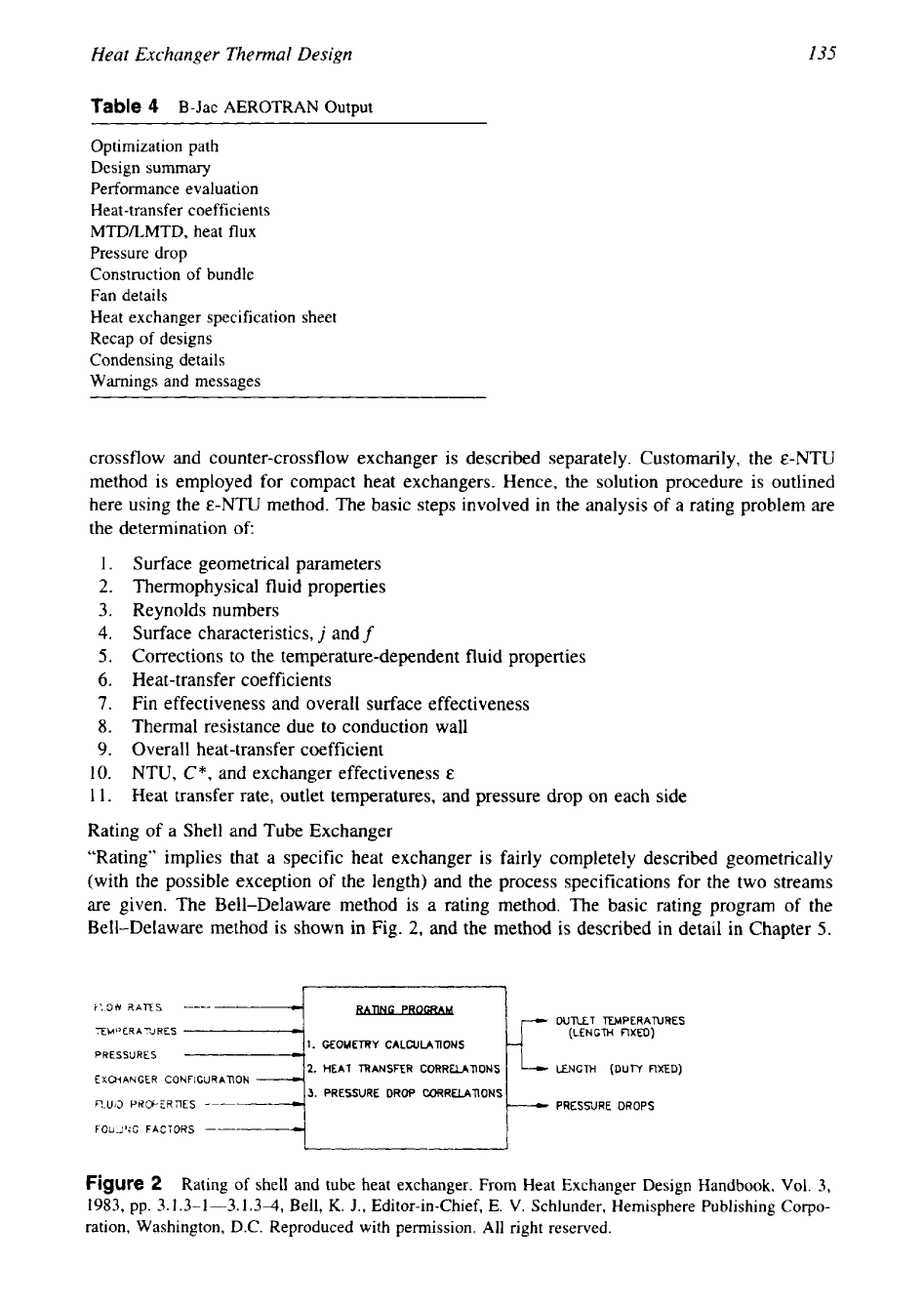

Rating of a Shell and Tube Exchanger

“Rating” implies that a specific heat exchanger is fairly completely described geometrically

(with the possible exception of the length) and the process specifications for the two streams

are given. The Bell-Delaware method is a rating method. The basic rating program

of

the

Bell-Delaware method

is

shown in Fig.

2,

and the method

is

described in detail in Chapter

5.

-

FLOW

RATES

EMPERAXRES

I=j

PRESSURES

1.

GEOMETRY

CALCULATIONS

OUTLET

TUvlPERATURES

(LENGTH

FIXED)

2.

HEAT

TRANSFER CORRELATIONS

EXCHANGER

CONFIGURATION

3.

PRESSURE DROP CORRELATIONS

fl.UID

PRWERTlES

PRESSURE

DROPS

FOULING

FACTORS

-

I

Figure

2

Rating

of

shell and tube heat exchanger. From Heat Exchanger Design Handbook, Vol.

3,

1983,

pp.

3.1.3-1-3.1.3-4,

Bell,

K.

J., Editor-in-Chief,

E.

V.

Schlunder, Hemisphere Publishing

Corpo-

ration, Washington, D.C. Reproduced with permission. All right reserved.

17

136

Chapter

3

1

2

3

4

1

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

IS

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

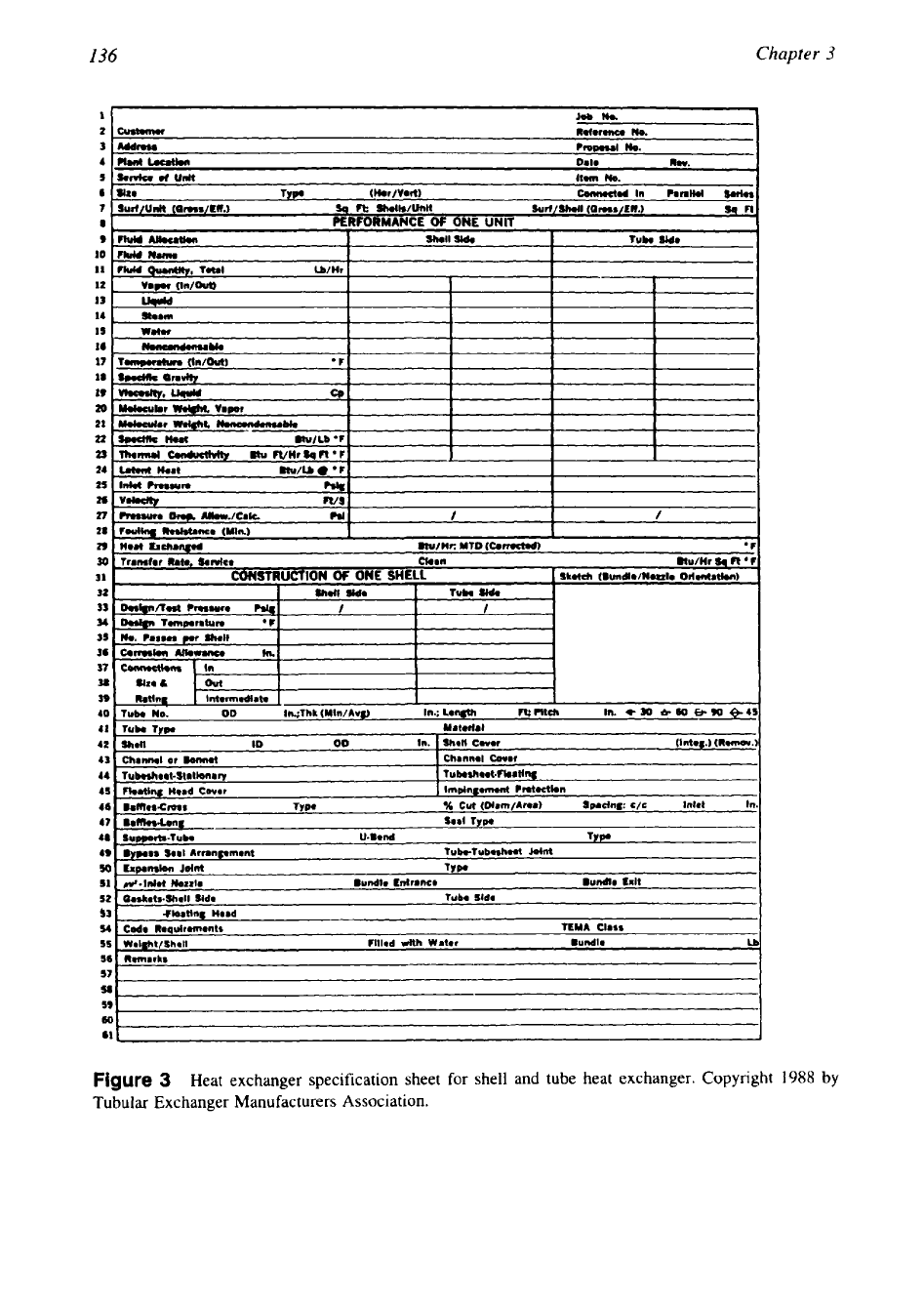

Figure

3

Heat exchanger specification sheet for shell and tube heat exchanger. Copyright

1988

Tubular Exchanger Manufacturers Association.

Heat Exchanger Them1 Design

137

(I.II~NT

JOIJ.

NO

L(

)(’All

ON

Dcsipn

Diitii

Shcct

ITEM

NO.

I%IIC

Fin

I

lcnl

Exchnnpr

2

No.

of

process

strcarndhlcrk

Flow:

cros~countcrlcms~-countcr

No.

blncks

scrlpar

pcr

train

3

DATA

FOR

ONE

TRAIN

4

Strciiin Iticntificiiiim

I

Units

I

A

I

t 3 I

c 1

U 1

E l

F

5

Fluid

Nnnic

1 1 1

1

I

I

I

I I

I I

43

JJ

Wcipht’Plock

-

dry

-

operating

\VciphtrTr;itn

-

operating

-

max

Inr

shipping

I

ti

i

I

I

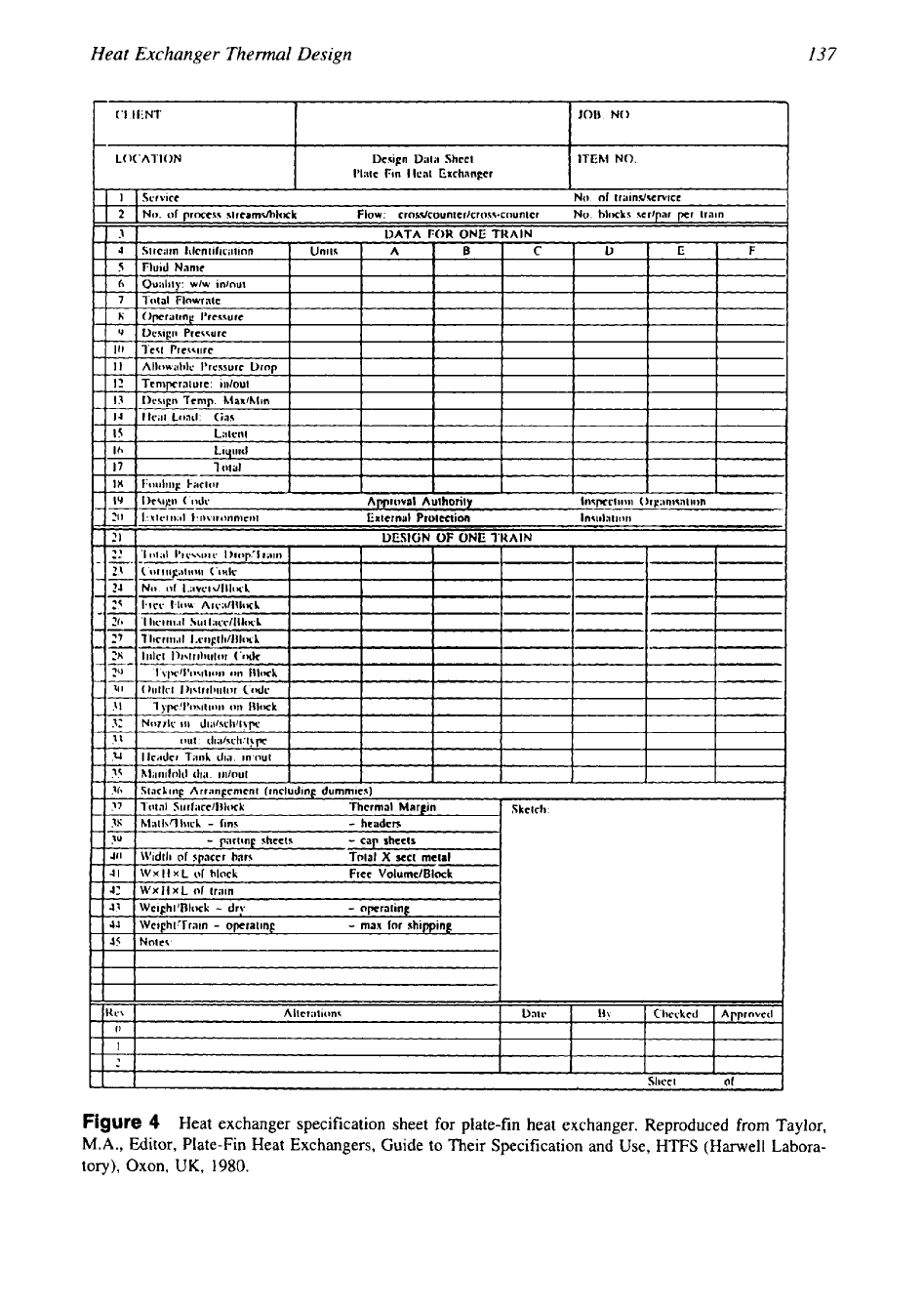

Figure

4

Heat exchanger specification sheet for plate-fin heat exchanger. Reproduced from Taylor,

M.A.,

Editor, Plate-Fin Heat Exchangers, Guide to Their Specification and Use, HTFS (Harwell Labora-

tory), Oxon,

UK,

1980.

I38

Chapter

3

4.2

Sizing

In a sizing problem, we determine the physical size (length, width, height, and surface area on

each side) of an exchanger. Inputs to the sizing problem are the fluid inlet and outlet tempera-

tures, flow rates, fouling factors, and the pressure drop on each side. The designer’s task is to

select construction type, flow arrangement, materials, and surface geometry on each side. With

the selection of construction types and surface geometries on each side, the problem then

reduces to the determination of the core dimensions for the specified heat-transfer and pressure-

drop performance. However, one can reduce the sizing problem to the rating problem by tenta-

tively specifying the dimensions, then predict the performance

[

11.

If the computed results do

not agree with the specified values, a new size

is

assumed and the calculations are repeated.

Size

of

a Heat Exchanger

For a given heat duty, the size of the heat exchanger is a function of the following parameters:

1.

Thermal effectiveness

2.

Fluid flow rate

3.

Secondary surface area per unit volume

4. Heat-transfer surface performance parameters

5.

Heat-transfer augmentation devices, if any

6,

Conductance ratio of the process fluids

Sensitivity Analysis

In a sizing problem, sometimes one is interested

in

determining the sensitivity of certain vari-

ables individually. For example, how does the heat transfer

vary

when changing the fin density

in

a compact heat exchanger with secondary surface? In such a case, one inputs a series of

values of fin densities at one time, runs the performance (rating) calculations, obtains a series

of results, and analyzes them.

Sizing of a Compact Heat Exchanger

The principle of compact heat exchanger sizing is discussed in Chapter

4,

Compact Heat

Exchanger Design.

Sizing of a Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger

Shell and tube heat exchanger design or sizing is based upon

(1)

design conditions, that is,

fluid flow rates, terminal temperatures, thermophysical fluid properties, and allowable pressure

drop;

(2)

assumptions, heat-transfer surface area, overall heat-transfer coefficient, or size,

length, or number of tubes; and

(3)

pressure

drop

across the heat exchanger

[7].

The design

conditions are fixed by overall plant design and determine the expected performance

of

the

exchanger, Trial-and-error calculations of the film coefficients area used to check the assump-

tions, which are also checked by an overall heat balance. Finally, the pressure drop is calculated

and compared with the allowable values. If the calculated pressure drop is too high, a new set

of assumptions

is

made and rechecked as before.

Heat Exchanger Optimization

The solution to the sizing problem in general is not adequate for the design of a new exchanger,

since other constraints in addition to pressure drop are imposed on the design, and the objective

of the design is to minimize the weight, volume, and heat-transfer surface, and minimum

pumping power, pressure drop, or other considerations in addition to meeting the required heat

transfer. This is achieved by heat exchanger optimization. Shah et al.

[8]

reviewed various

methods used in the literature for heat exchanger optimization and described numerical nonlin-

ear programming techniques.

Heat Exchanger Thermal

Design

139

4.3

Solution to the Rating and Sizing

Problem

Now let

us

discuss the basic steps involved in the solution of the two design problems, the

rating and sizing.

Rating

The basic steps involved

in

the solution to the rating problem are as follows

[9].

E-NTU Method.

1.

Compute

C*

and NTU from the input specifications.

2.

Determine

E

for known NTU,

C*,

and the flow arrangement,

3.

Compute

q

from

and outlet temperatures from

and compare with those of step

2.

LMTD Method.

1.

Compute

R

from

R

=

C,/C,.

2.

Assume the outlet temperatures to determine

P,

or assume

P

and calculate outlet tempera-

tures. Also calculate LMTD.

3.

Determine LMTD correction factor,

F.

4.

Determine q from

q

=

UAF(LMTD).

5.

Evaluate the outlet temperatures from known

q,

C,,

and

C,,,

and compare with those of

step

2.

6.

Repeat steps

2-5

until the desired convergence is achieved.

Solution to the Sizing Problem

In a sizing problem,

U,

C,,

Ch,

and the terminal temperatures are specified, and the surface

area

A

is to be determined. Or

U

may be calculated from the specified convective film coeffi-

cients and the fouling resistances. The basic steps involved in sizing

by

the

E-NTU

and LMTD

methods are as follows

[9].

E-NTU Method.

1.

Compute

E

from the specified inlet and outlet temperatures and calculate

C*.

2.

Determine NTU from known

E,

C*,

and the flow arrangement,

3.

Calculate the required surface area

A

from

A

=

(NTU)C,,,/U and from terminal tempera-

tures.

LMTD Method.

1.

Compute

P

and

R

from the specified inlet and outlet temperatures.

2.

Determine

F

from

F-P

curves for known

P, R,

and the flow arrangement.

3.

Calculate the heat transfer rate q and LMTD.

4.

Calculate

A

from

A

=

q/[U

F(LMTD)].

A trial-and-error approach is needed for the solution of the rating problem by the LMTD

method.

140

Chapter

3

5

COMPUTER-AIDED

THERMAL

DESIGN

In the present computer era, thermal design is almost exclusively performed by industry using

computers. Chenoweth et al.

[

101, Bell

[

111, and Palen

[

121 discuss computer-aided design

methods for shell and tube exchangers. Shah [13] discusses in detail the computer-aided ther-

mal design methodology for both compact and shell and tube exchangers. Although there are

similarities in the overall structure of the computer programs, the details

vary

significantly

between compact and shell and tube exchangers. In the following subsections, we discuss the

structure of a computer design method for thermal design of (1) compact heat exchangers and

(2)

shell and tube heat exchangers. Salient features of this computer program are discussed.

5.1

Overall Structure

of

a

Thermal Design Computer Program

The overall structure of a thermal design computer program for a compact heat exchanger (Fig.

5),

consists at a minimum of these subroutines [13]: (1) input subroutines,

(2)

geometry subrou-

tine,

(3)

fluid properties subroutine,

(4)

surface characteristics subroutine,

(5)

fin efficiency

subroutine,

(6)

E-NTU subroutine,

(7)

pressure drop subroutine,

(8)

rating problem subroutine,

(9)

sizing problem subroutine, (10) optimization subroutines, and (1 1) output subroutines.

Input Subroutines.

These serve (1) to feed the problem specifications/process data, and

(2)

to convert the given unit from one system to other. The input subroutine should be structured

to verify whether the input data is within normal ranges and to give a warning message if

any

inconsistency is found.

Geometry Subroutine.

The geometry subroutine calculates the various surface geometrical

parameters for commonly used surfaces. For uncommon surfaces, calculated values are fed

through the input subroutine or the terminal.

Fluid Properties Subroutine.

This subroutine provides fluid properties for commonly used

fluids in the form of specific or generalized correlations together with heat release/added curve.

For others, they may be transferred through input data. Methods or correlations should

be

incorporated for evaluating properties of fluid mixtures.

Surface Characteristics Subroutine.

For common surfaces,

j

and

f

versus Reynolds number

data may be stored in the subroutine, or correlations may be built in. For uncommon surfaces,

such information may be transferred through the input subroutine or through the terminal.

Fin Eficiency Subroutine.

This subroutine calculates the fin efficiency and overall surface

effectiveness for various types of extended surfaces.

E-NTU

Subroutine.

E-NTU formulas for all flow arrangements of interest are built into this

subroutine. The subroutine could be used for solving both the rating and sizing problems. That

means, for a rating problem, it computes

E

when NTU and

C*

are given, and for a sizing

problem it computes NTU when

E

and

C*

are given.

Pressure

Drop

Subroutine.

The friction factor

f

is fed through the surface characteristic sub-

routine. Provisions must be made to compute the pressure drop in manifolds, headers, turns,

or sudden area changes at manifold/header inlet/outlet sections.

Rating Problem Subroutine.

Since outlet temperatures are not known initially, they are there-

fore guessed, and the solution to the rating problem is iterated on the fluid properties once or

twice until the desired convergence is achieved.

Sizing Problem Subroutine.

All of the subroutines (except the rating problem subroutine)

discussed so far are used in sizing problem. The sizing problem is solved by first determining

Heat Exchanger Thermal Design

141

an approximate mass velocity

G

that accounts for both specified heat transfer and pressure

drop. The sizing problem is iterated on

G

until the desired convergence is met.

Optimization Subroutines.

In a sophisticated computer program, not only are the options of

solving straightforward rating and sizing problems available, but also optimization procedures

are incorporated. Such a program logically searches among feasible solutions and arrives at an

optimum objective function.

Output Subroutines.

These serve to print all the output results in the desired units along with

the desired input data and error messages. All important output results should be verified for

their basic validity.

Guidelines on Program Logic

Shah

[

131 lists several points that should be taken into account in the initial organization and

writing of the program:

1. The program should be written in a modular form containing many subroutines rather than

one big main program. This allows flexibility in thorough debugging and modification of

the program while running the program.

2.

Error messages subroutines should

be

inbuilt that monitor the warning and minor and

major errors for the input data and throughout the problem execution.

3.

All of the iterative calculations should have a maximum number of iterations specified.

4.

For a sophisticated computer program to be good, it must satisfy the requirements of

individuals with diverse yet specific interests. The program should provide correct answers

and ease of use, and it will be viable only as long its developers provide user support

[

101.

5.2

Program Structure for a Shell and Tube Exchanger

For a shell and tube exchanger, most of the structure of the subroutines mentioned

so

far are

common but the contents slightly

vary

as follows:

1.

Geometry subroutine: This should include the auxiliary calculations on the shell side and

a range of geometries including the shell type, number

of

shells

in

series, number

of

shells

in parallel, shell diameter, tube length, baffles and baffle cut, various shell-side clearances,

tube count, and nozzles.

2.

Various shell-side correction factors calculated for heat transfer and pressure drop.

3.

The thermal effectiveness subroutine:

P-NTU,

relations should be built in for all possible

flow arrangements and TEMA shells, including the check for “temperature cross.”

6

PRESSURE-DROP ANALYSIS, TEMPERATURE-DEPENDENT

FLUID PROPERTIES, PERFORMANCE FAILURES, FLOW

MALDISTRIBUTION, FOULING, AND CORROSION

6.1

Heat Exchanger Pressure-Drop Analysis

The term “pressure drop” refers to the pressure loss that is not recoverable in the circuit. The

determination of pressure drop in a heat exchanger is essential for many applications for at

least two reasons [9]:

1.

The operating cost of a heat exchanger is primarily the cost of the power to run fluid-

moving devices such as pumps, fans, and blowers. This pumping power,

P,,,

is proportional

to the exchanger pressure drop as given by

142

Chapter

3

P,

-MAP

-

__

P

where

M

is the mass flow rate,

Ap

is

the pressure drop, and

Q

is the fluid density.

2.

The heat-transfer rate can be significantly influenced

by

the saturation temperature change

for a condensing/evaporating fluid for a large pressure drop.

The principle

of

pressure-drop analysis for a heat exchanger is described by Kays

[14}

and is extended to all types of heat exchangers. In this section, pressure-drop analysis for

various types

of

heat exchangers as per Ref.

9 is

discussed.

Pressure Drop Evaluation for Heat Exchangers

The pressure drop associated with a heat exchanger may be considered as having two major com-

ponents:

(1)

pressure drop associated with the core or matrix, and

(2)

pressure drop in inlet and

outlet headers, manifolds, nozzles, or ducting due

to

change in flow area, flow turning, etc. In this

section, core pressure drop for extended surface exchangers, regenerators, and tubular exchangers

is presented, followed by the pressure drop associated with bends and flow turnings.

Pressure Drop Through a Heat Exchanger

The pressure drop on any one side consists

of

pressure losses due to sudden contraction at the

core inlet,

Ap,.?,

core pressure drop,

Ap2-3,

and the pressure rise due to sudden expansion at

the core outlet,

Ap3.+

Therefore, the total pressure drop on any one side of the exchanger

is

given by

Ap

=

ApI.2

+

Ap2.7

-

Ap7-j

(2)

Pressure drop through a heat exchanger is schematically shown in Fig.

6.

This figure is based

on Ref.

14.

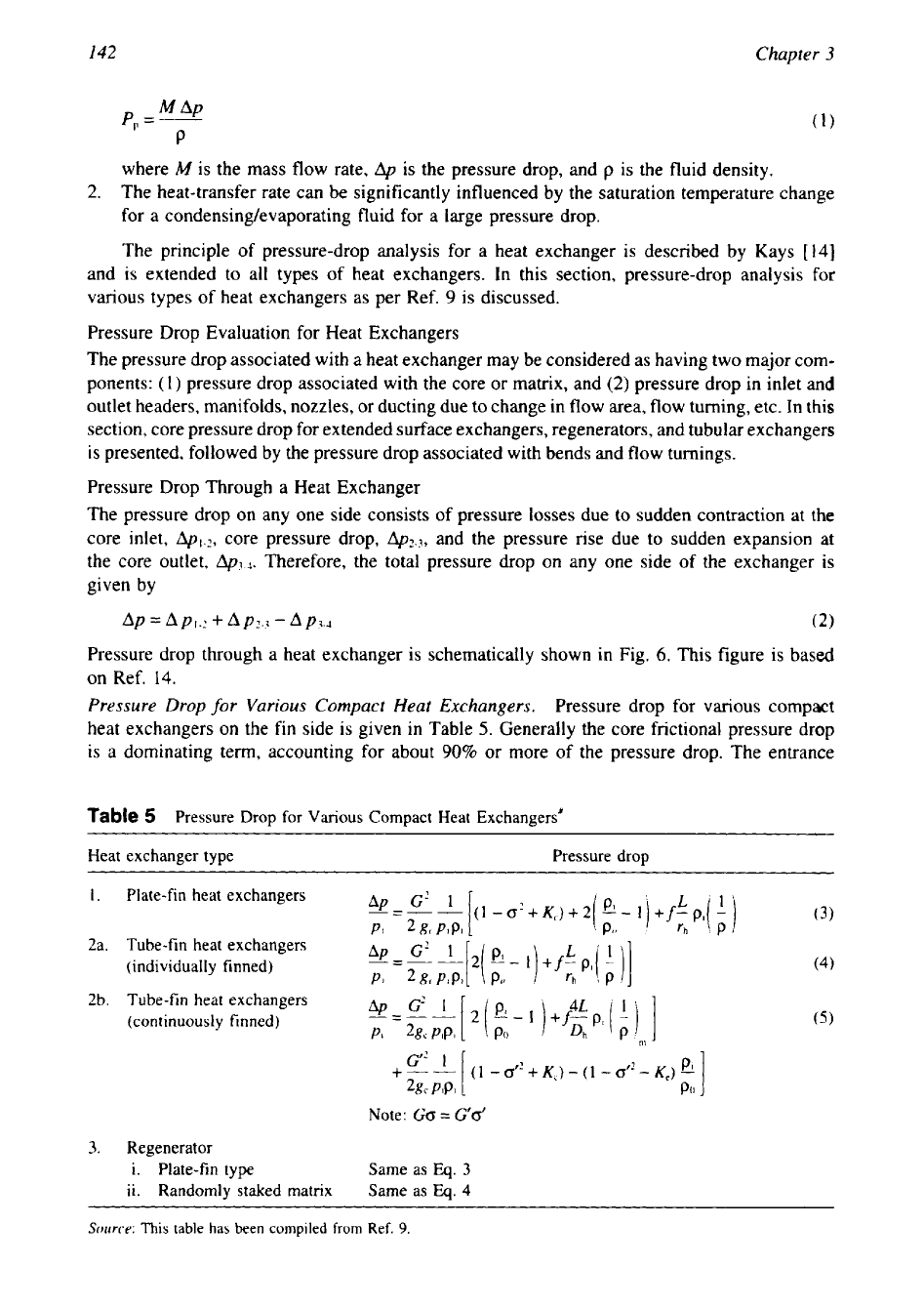

Pressure Drop for Various Compact Heat Exchangers.

Pressure drop for various compact

heat exchangers on the fin side is given in Table

5.

Generally the core frictional pressure drop

is a dominating term, accounting for about

90%

or more of the pressure drop. The entrance

Table

5

Pressure Drop

for

Various Compact Heat Exchangers’

Heat exchanger type Pressure drop

1.

Plate-fin heat exchangers

(3)

2a. Tube-fin heat exchangers

(individually finned)

(4)

2b. Tube-fin heat exchangers

(continuously finned)

PI

2gc

PIP1

4L

Note:

Go

=

G’d

3.

Regenerator

i.

Plate-fin type Same as

Eq.

3

ii. Randomly staked matrix

Same as

Eq.

4

Source:

This

table

has

been compiled from Ref.

9.

143

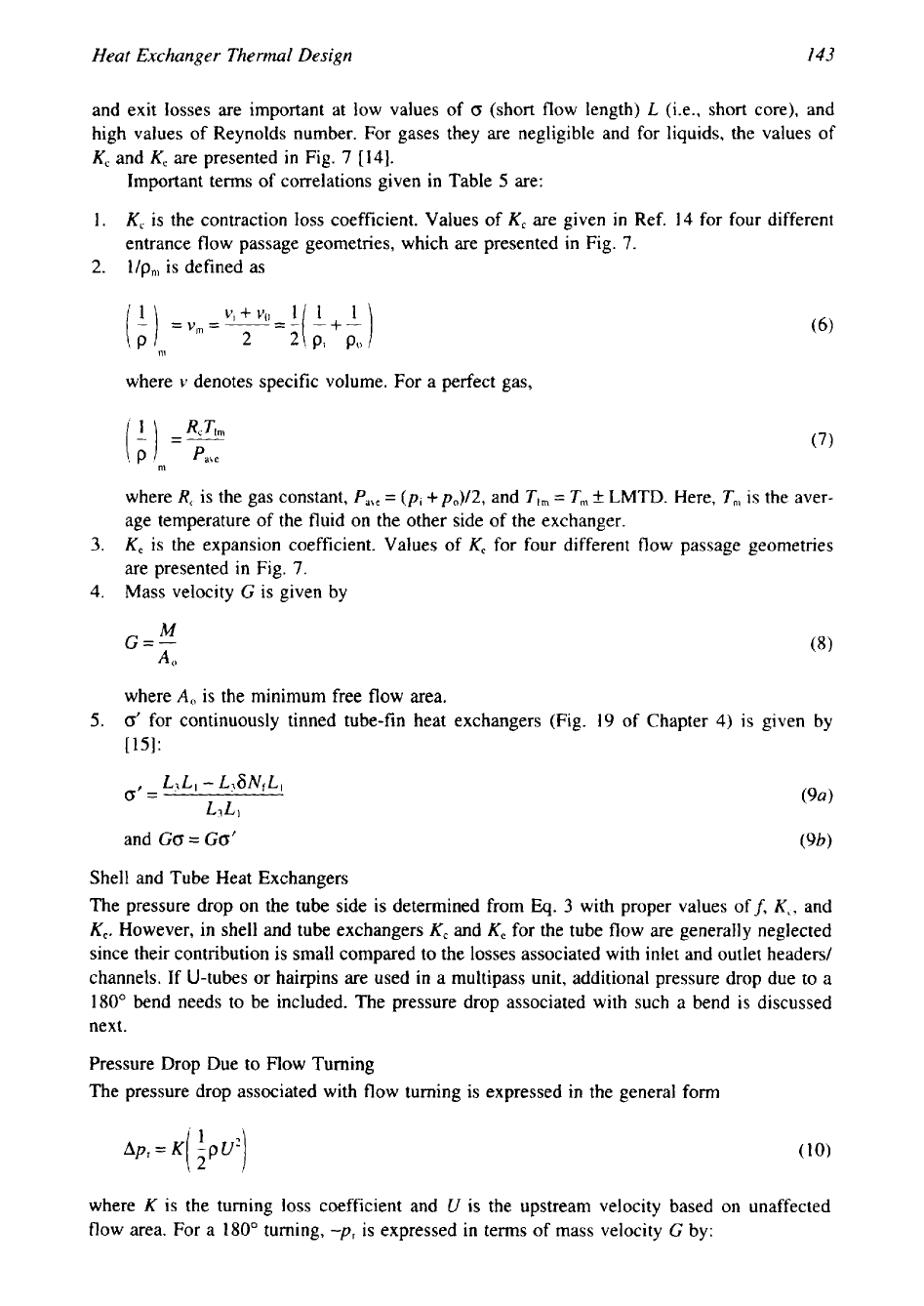

Heat Exchanger Thermal Design

and exit losses are important at low values of

0

(short flow length)

L

(i.e., short core), and

high values of Reynolds number. For gases they are negligible and for liquids, the values of

K,

and

K,

are presented in Fig.

7

[

141.

Important terms of correlations given in Table

5

are:

1.

K,

is the contraction loss coefficient. Values of

K,

are given in Ref.

14

for four different

entrance flow passage geometries, which are presented in Fig.

7.

2.

l/p,,,

is defined as

where

v

denotes specific volume. For a perfect gas,

(7)

where

R,

is the gas constant,

Pabe

=

(p,

+po)/2,

and

Tlm

=

T,,,

k

LMTD. Here,

T,

is the aver-

age temperature

of

the fluid on the other side of the exchanger.

3.

K,

is the expansion coefficient. Values of

K,

for four different flow passage geometries

are presented in Fig.

7.

4.

Mass velocity

G

is given by

where

A,

is the minimum free flow area.

5.

0'

for continuously tinned tube-fin heat exchangers (Fig.

19

of Chapter

4)

is given by

[15]:

Shell and Tube Heat Exchangers

The pressure drop on the tube side is determined from

Eq.

3

with proper values off,

K,,

and

K,.

However, in shell and tube exchangers

K,

and

K,

for the tube flow are generally neglected

since their contribution

is

small compared to the losses associated with inlet and outlet headers/

channels. If U-tubes or hairpins are used in a multipass unit, additional pressure drop due

to

a

180"

bend needs to be included. The pressure drop associated with such a bend is discussed

next.

Pressure Drop Due to mow Turning

The pressure drop associated with flow turning is expressed in the general form

where

K

is the turning loss coefficient and

U

is the upstream velocity based

on

unaffected

flow area. For a

180"

turning,

-pr

is

expressed in terms of mass velocity

G

by: