Kenny Anthony. Ancient Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy Volume 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

succeeded in doing so. The de Anima itself, as we have seen, contains a

passage that strongly suggests an immortal element in the human soul;

and in the very section of the work that sets out most clearly the theory of

the soul as the form of an organic body, Aristotle tells us that it is an open

question whether the soul is in the body as a sailor in a ship (2. 1. 413a9). But

that is a classic formulation of the dualist conception of the relation of soul

to body.

Hellenistic Philosophy of Mind

No ancient author between Aristotle and Augustine formulated a com-

parably rich philosophy of mind. The philosophical psychology of Epi-

curus show s little advance on that of Democritus. For him the soul, like

everything else, consists of atoms, which diVer from other atoms only in

being smaller and subtler, more Wnely structured even than those that

constitute the winds. It is nonsense to say that the soul is incorporeal:

whatever is not body is merely empty void. The soul has the major

responsibility for sensation, but only through its position in the body–-

soul compound. At death its atoms are dispersed and cease to be capable

of sensation because they no longer occupy their appropriate place in a

body (LS 14b).

The third book of Lucretius’ great poem On the Nature of Things is devoted

to psychology. He distinguishes initially between animus and anima (34–5).

The animus, or mind, is a part of the body just like a hand or foot; this is

shown by the fact that a body becomes inert once it has breathed its last

breath. The mind is a part of the anima, or soul; it is the dominant part,

located in the heart. The rest of soul is spread throughout the body and

moves at the behest of mind. Mind, soul, and body are closely interwoven,

as we see when fear causes the body to tremble and bodily wounds cause

the mind to grieve. Mind and soul must be corporeal or they could not

move the body—to move it they must touch it, and how could they touch

it unless they were themselves bodily (160–7)? Mind is very light and Wne

textured, like the bouquet of wine—a dead body, after all, weighs little less

than a live one. It is composed of Wre, air, wind, and a fourth nameless

element. Mind is more important than soul; once mind goes, soul follows

soon after, but m ind can survive great damage to soul (402–5).

248

SOUL AND MIND

Some say that the body does not perceive or sense anything, but only

the soul, conceived as an inner homunculus. Lucretius argues ingeniously

against this primitive view. If the eyes are not doing any seeing, but are

merely doors through which the mind sees, then we ought to be able to see

more clearly if our eyes have been torn out, because a man in a house can

see out much better if doors and doorposts are removed (367–9).

The goal of Lucretius’ discussion of mind and soul is to prove that they

are both mortal, and thu s to take away the grounds on which people fear

death. Water Xows out of a smashed vessel: how much faste r must soul’s

tenuous Xuid leak away once the body is broken! The mind develops with

the body and will decay with the body. The mind suVers when the body is

sick, and is cured by physical medicine. These are all clear marks of

mortality.

What has this bugbear, death, to frighten man,

If souls can die, as well as bodies can?

For, as before our birth we felt no pain,

When Punic arms infested land and main,

When heaven and earth were in confusion hurled,

For the debated empire of the world,

Which awed with dreadful expectation lay,

Sure to be slaves, uncertain who should sway:

So, when our mortal frame shall be disjoined,

The lifeless lump uncoupled from the mind,

From sense of grief and pain we shall be free;

We shall not feel, because we shall not be.

(830–40, trans. Dryden)

We are only we, Lucretius says in conclusion, while souls and bodies in one

frame agree.

The Epicureans gave an atomistic account of sense-perception, in particu-

lar of vision. Bodies in the world throw oV thin W lms of the atoms of which

they are made, which retain their original shape and thus serve as images

(eidola). These Xy around the world with astonishing speed, and perception

occurs when they make contact with atoms in the so ul. When we see mental

images, this is the result of even more tenuous Wlaments joining together in

the air, like spider’s web or gold leaf. Thus, the image of a centaur is the result

of the interweaving of a human image and a horse image; it can enter the

mind during sleep as well as when awake. We are always surrounded by

249

SOUL AND MIND

countless such Wne images, but we are only aware of those on which the

mind turns the beam of its attention (Lucretius 4. 722–85).

The Stoics, like the Epicureans, had a materialist concept of soul. We live

to the extent that we breathe, Chrysippus argued; soul is what makes us

live, and breath is what makes us breathe, so soul and breath are identical

(LS 53g). The heart is the seat of the soul: there resides the soul par excellence,

the master-faculty (hegemonikon) which sends out the senses to bring back

reports on the environment for it to evaluate. Sense-perception itself takes

place exclusively within the master-faculty (LS 53m). The master-faculty is

material like the rest of the soul, but it is capable of surviving, at least

temporarily, separation from the body at death (LS 53w). There is not,

however, any real personal immortality for the Stoics: at best, the souls of

the wise after death can be absorbed into the divine World Soul that

permeates and governs the universe.

Some Stoics compared the human soul to an octopus: eight tentacles

sprouted out from the master-faculty into the body, Wve of them being the

senses, one being a motor agent to eVect the movement of the limbs, one

controlling the organs of speech, and the Wnal one a tube to carry semen to

the generative organs. Each of these tentacles was made out of breath (LS

53h, l ).

It will be noted that of the eight tentacles Wve are aVerent, and three

eVerent. This reXects an important clariWcation the Stoics introduced into

philosophical psychology. Plato and Aristotle had been principally inter-

ested in dividing faculties of the soul hierarchically, on the basis of the

cognitive or ethical value of the objects of the faculty: thus intellect came

above sensation, and rational choice above animal desire. The Stoics were

well aware of the diVerence between the capacities of rational language

users and dumb animals (LS 53 t) but they regarded as equally important a

division of faculties that is vertical rather than horizontal. The distinction is

thus stated by Cicero, quoting Panaetius:

Minds’ movements are of two kinds: some belong to thought, and some to

appetition. Thought is principally concerned with the investigation of truth and

appetition is a drive to action. (OV 1. 132).

The distinction between cognitive and appetitive faculties cuts across the

distinction between sensory and intellectual faculties. In later antiquity and

in the Middle Ages philosophers came to accept the following scheme:

250

SOUL AND MIND

Intellect Will

Sensation Desire

This combines the Aristotelian distinction between the rational and the

animal level, with the Stoic distinction between the cognitive and appeti-

tive dimension.

Will, Mind, and Soul in Late Antiquity

It is often said that in classical philosophy there is no concept of the will. Some

have gone so far as to say that in Aristotle’s psychology the will does not occur

at all, and the concept was invented only after eleven further centuries of

philosophical reXection. Certa inly, it is undeniable that there is no Aristotel-

ian expression that exactly corresponds to the English expression ‘freedom of

the will’, and scholars have concluded that he had no real grasp of the issu e.

This criticism of Aristotle depends on a certain view of the nature of the

will. In modern times philosophers have often thought of the will as a

phenomenon of introspective consciousness. Acts of the will, or volitions,

are mental events that precede and cause certain human actions; their

presence or absence make the diVerence between voluntary and involun-

tary actions. The freedom of the will is to be located in the indeterminacy

of these introspectible volitions.

It is not clear how far the Epicureans and Stoics shared this conception

of the causation of human action, but it is certain that this concept of the

will is not to be found in Aristotle. But this is to his credit, for the concept is

radically Xawed and has been discredited in recent times. A satisfactory

philosophical account of the will must relate human action to ability,

desire, and belief. It must contain a treatment of voluntariness, a treatment

of intentionality, and a treatment of rationality. Aristotle’s treatises contain

ample material relevant to the study of the will thus understood, even

though his concepts do not exactly coincide with those that it would

nowadays be natural to employ.

Aristotle deWned vol untariness as follows: something was voluntary if it

was originated by an agent free from compulsion or error (NE 3. 1.

1110a1 V.). In his moral system an important role was also played by the

concept of prohairesis, or purposive choice: the choice of an action as part of

251

SOUL AND MIND

an overall plan of life (NE 3. 2. 1111b4 V.). His concept of the voluntary was

too clumsily deWned, and his concept of prohairesis too narrowly deWned, to

demarcate the everyday moral choices that make up our lives. The fact that

there is no English word corresponding to ‘prohairesis’ is itself a mark of

the awkwardness of the concept: most of Aristotle’s moral terminology has

been naturalized into all European languages.

Though he has a rich and perceptive account of practical reasoning,

Aristotle has no technical concept corresponding to our concept of inten-

tion: that is to say, of doing A in order to bring about B, of choosing means to

ends as well as pursuing ends for their own sake. Voluntariness is a broader

concept than intention: it includes whatever we bring about knowingly but

unintentionally, as an undesired consequence of action. Prohairesis is a

narrower concept: it restricts the goal of the intention to the enactment

of a grand pattern of life.

These defects in Aristotle’s treatment of the appetitive side of human life

are the truth behind the exaggerated claim that he had no concept of the

will. It was, indeed, the reXection of Latin philosophers which led to the

full development of the concept, and this reXection can be seen in copious

form in the writings of Augustine.

In the second and third centuries further developments called for

modiWcation of Aristotelian philosophy of mind. The physician Galen

(129–99) discovered that for the operation of the muscles nerves arising

from the brain and spinal cord have to be active. Thus the brain, rather

than the heart, should be regarded as the principal seat of the soul. But like

the Stoics, Galen distinguished between a sensory soul and a motor soul,

the former associated with aVerent nerves travelling to the brain, the latter

with motor nerves originating in the spinal cord.3

The peripatetic commentator Alexander of Aphrodisias, who X ourished

in the Wrst decades of the third century, identiW ed the Active Intellect of

the de Anima with the unmoved mover of Metaphysics K. Alexander thus

began a long tradition of interpretation which X ourished, in diVerent

forms, among later commentators, especially in the Arab world.

A human being at birth, he maintained, had only a material or physical

intellect; true intelligence is acquired only under the inXuence of the

3 M. R. Bennett, and P. M. S. Hacker, Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience (Oxford: Blackwell,

2003), 20.

252

SOUL AND MIND

supreme divine mind. In consequence, the human soul is not immortal:

the best it can do is to think immortal thoughts by meditating on the

Motionless Mover (de An. 90. 11–91. 6).

In reaction to the m ortalism of the Epicureans, Stoics, and later Peripa-

tetics, Plotinus set out, in Plato’s footsteps, to prove that the individual soul

is immortal. He sets out his case in one of his earliest writings, Ennead 4. 7

(2), On the Immortality of the Soul. If the soul is the principle of life in living

beings, it cannot itself be bodily in nature. If it is a body, it must be either

one of the four elements, earth, air, Wre, and water, or a compound of one

or more of them. But the elements are themselves lifeless. If a compound

has life, this must be due to a particular proportion of the elements in the

compound: but this must have been conferred by something else, the cause

that provides the recipe for and combines the ingredients of the mixture.

This something else is soul (4. 7. 2. 2).

Plotinus argues that none of the functions of life, from the lowliest form

of nutrition and growth to the highest forms of imagination and thought,

could be carried out by something that was merely bodily. Bodies undergo

change at every instant: how could something in such perpetual Xux

remember anything from moment to moment? Bodies are divided into

parts and spread out in space: how could such a scattered entity provide

the uniWed focus of which we are aware in perception? We can think of

abstract entities, like beauty and justice: how can what is bodily grasp what

is non-bodily? (4. 7. 5–8). The soul must belong, not to the world of

becoming, but to the world of Being (4. 8. 5).

Plotinus is aware that there are those who say that the soul, though not

a body itself, nonetheless is dependent on body for its existence. He recalls

Simmias’ contention in the Phaedo that the soul is nothing more than an

attunement of the body’s sinews. He neatly turns the tables on that

argument. When a musician plucks the strings of a lyre, he says, it is the

strings, not the melody that he acts upon; but the strings would not be

plucked unless the melody called for it (3. 6. 4. 49–80; 4. 7. 8).

Plotinus clearly maintains the personal immortality of individuals. It

would be absurd to suggest that Socrates will cease to be Socrates when he

goes from hence to a better world hereafter. Minds will survive in that

better world, because nothing that has real being e ver perishes (4. 3. 5).

However, the exact signiWcance of this claim is unclear, since Plotinus also

maintains that all souls form a unity, bound together in a superior World-

253

SOUL AND MIND

Soul, from which they have originated and to which they return (3. 5. 4).

We shall learn more about this World-Soul in Chapter 9, when we come to

discuss Plotinus’ theology.

One of those who learnt most from Plotinus’ speculations was the

young Augustine. His own original contribution to philosophy of mind,

however, is to be found in his writing on freedom. In his de Libero Arbitrio,

written in the year of his conversion to Christianity, he defends a form of

libertarianism that diVers both from the compatibilism we saw in an earlier

chapter when considering Chrysippus, and from the predestinarianism for

which the later, Christian, Augustine is notorious.

In the third book the question is raised whether the soul sins by

necessity. We have to distinguish, we are told, three senses of ‘necessity’:

nature, certainty, and compulsion. Nature and compulsion are incompat-

ible with volunt ariness, and only voluntary acts are blameable. If a sinner

sins by nature or by compulsion, the sin is not voluntary. But certainty is

compatible with voluntariness: it may be certain that X will sin, and yet X

will sin voluntarily and will rightly be blamed.

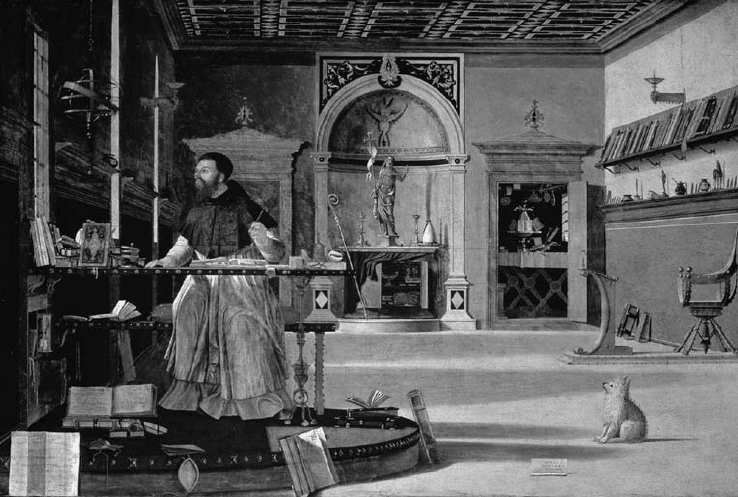

St Augustine in his study (Vittorio Carpaccio, S. Giorgio, Venice)

254

SOUL AND MIND

Consider Wrst the necessity of natu re. The soul does not sin by

necessity in the way that a stone falls by necessity of nature: the soul’s

action in sinning is voluntary. Both the soul and the stone are agents, but

the soul is a voluntary and not a natural agent. The diVerence is this: ‘it is

not in the stone’s power to arrest its downward motion, but unless the soul

is willing it does not so act a s to abandon what is higher for what is lower’

(iii.2).

As we saw in considering Chrysippus, voluntariness can be deWned by

reference to the power to do otherwise (liberty of indiVerence) or

by reference to the power to do what one wants (liberty of spontaneity).

In the de Libero Arbitrio Augustine combines the two approaches. The soul’s

motions are voluntary, because the soul is doing what it wants. ‘I do not

know what I can call my own’, Augustine says, ‘if the will by which I want

or reject is not my own.’ But the power to want is itself a two-way power.

‘The motion by which the will turns in this or that direction would not be

praiseworthy unless it was voluntary and placed within our power.’ Nor

could the sinner be blamed when he turns the hinge (cardo) of the will

towards the nether regions (iii. 3).

Augustine oVers to prove that wanting is in our power. The exact lines

of his proof are not clear. On one interpretation it goes like this. Doing X is

in our power if we do X whenever we want. But whenever we want, we

want. Therefore wanting is in our power. This seems too easy: surely the

Wrst premiss is incompl ete. It should read: Doing X is in our power if we do

X whenever we want to do X. The second premiss would then have to

read: Whenever we want to want to do X we want to do X. This would give

us Augustine’s conclusion: whatever X is, wanting X is in our power. But

one may question the second premiss. May we not have a second-order

want to want something, without having the Wrst-order want itself? When

Augustine wanted to be chaste, but not yet, was he really wanting to be

chaste, or only wan ting to wan t to be chaste?

If it is in my power to do X, in the sense earlier outlined by Augustine,

then it must be in my power not to do X. This weakens his argument to

show that wanting is in our power. For whatever plausibility there is in the

claim that if I want to want something I want it, there is none in the claim

that if I want not to want something then I do not want it. I may very

sincerely want to give up smoking: that does not prevent my passionate

want for a cigarette at this moment.

255

SOUL AND MIND

No doubt Augustine can respond by making distinctions between diVer-

ent kinds of wanting: but in the present context it would not be proWtable

to follow further his analysis of volition. The part of the de Libero Arbitrio

most relevant to the issue of determinism and freedom is his consideration

of the foreknowledge of God. Augustine believed that at any moment God

foreknew all future events. He can then construct the following argument

against the possibility of voluntary sin.

(1) God foreknew that Adam was going to sin.

(2) If God foreknew that Adam was going to sin, necessarily Adam was

going to sin.

(3) If Adam was necessarily going to sin, then Adam sinned necessarily.

(4) If Adam sinned necessarily, Adam did not sin of his own free will.

(5) Adam did not sin of his own free will.

The line of argument here is clearly the Christian heir to the discussion of

the sea-battle in Aristotle and the Master Argument of Diodorus: in each

case, in diVeren t ways, the necessity of a past state or event is used as a

starting point from which to derive the necessity of a future event. In the

Greeks the starting premiss is logical, here it is theological.

Augustine proposes to disarm the argument by the distinction between

certainty, on the one hand, and natu ral causation or compulsion, on the

other. I can know something without causing it (as when I know it because

I remember it). I can be certain that someone is about to do something

without in any way compelling him to do it. Accordingly, we can distin-

guish the senses of ‘necessity’ in the argument above. In the second

premiss, and the antecedent of the third premiss ‘necessarily’ must be

taken as ‘certainly’. In the fourth premiss and the consequent of the

third premiss ‘necessarily’ must be taken as ‘under compulsion’. Because

of the resulting equivocation in the third premiss, the argument fails.

Augustine’s response does not wholly convince: there is surely no exact

analogy between conjectural human knowledge of the future and omni-

temporal divine omniscience. The diYculties that his treatment leaves

unsolved were taken up by many future generations of Christian theolo-

gians; but his discussion can Wttingly be taken as representative of the Wnal

stage of reXection on determinism in antiquity.

256

SOUL AND MIND

8

How to Live:

Ethics

A

mong the sayings attributed to the earliest Greek philosophers, many

have a moral content. Thales, for instance, is credited with an early

version of ‘Do as you would be done by’: asked how we could best live, he

replied, ‘if we do not ourselves do what we blame others for doing’. In

more ambiguous vein, when asked by an adulterer if he should swear he

was innocent, he replied, ‘Well, perjury is no worse than adultery’ (D.L. 1.

37). Oracular utterances of a similar kind are to be found in Heraclitus: ‘It is

not good for men to get all they want’ (DK 22 B110); ‘a man’s character is

his destiny’ (DK 22 B117). Other philosophers took stances on particular

moral issues: thus Empedocles attacked meat-eating and animal sacriWce

(DK 31 B128, 139). But it is not until Democritus that we Wnd any sign of a

philosopher with a moral system.

Democritus the Moralist

Democritus was eloquent on ethical topics: sixty pages of his fragments, as

recorded in Diels–Kranz, are devoted to moral counsel. Much of it is of a

homespun, agony-aunt type: don’t take on tasks above your power, don’t

be envious of the rich and famous: think of all the people who are worse oV

than you are, and be contented with your lot (DK 68 B91). Do not try to

know everything, or you will end up knowi ng nothing (DK 68 B69). Don’t

blame bad luck when things go wrong through your own fault: you can

avoid drowning by learning to swim (DK 68 B119, 172). Accept favours only