Kenny Anthony. Ancient Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy Volume 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

lineaments of his ideal philosophical type of homoerotic love. When we

reach the point where we have a man and a boy and four horses all in bed

together, the metaphor has obviously got quite out of hand (256a).

The anatomy of the soul is more soberly described in the Republic.In

book 4 Socrates suggests that the soul contains three elements, just as his

imaginary state contains three classes. ‘Do we learn things with one part,’

he asks, ‘feel anger with another, and with yet a third desire the pleasures

of food and sex and the like? Or when we have such impulses are we

operating with our whole soul?’ (436a–b). He Wnds his answer by attending

to the phenomena of mental conXict. A man maybe thirsty and yet

unwilling to drink (perhaps because of doctor’s orders): this shows that

there is one part of the soul that reXects and a diVerent one that feels bodily

desires. The Wrst can be called reason (to logistikon) and the second appetite (to

epithymetikon; 439d). Now anger cannot be attributed to either of these

elements: not to appetite, for we may feel disgust at our own perverted

desires; not to reason, because children have tantrums before they reach

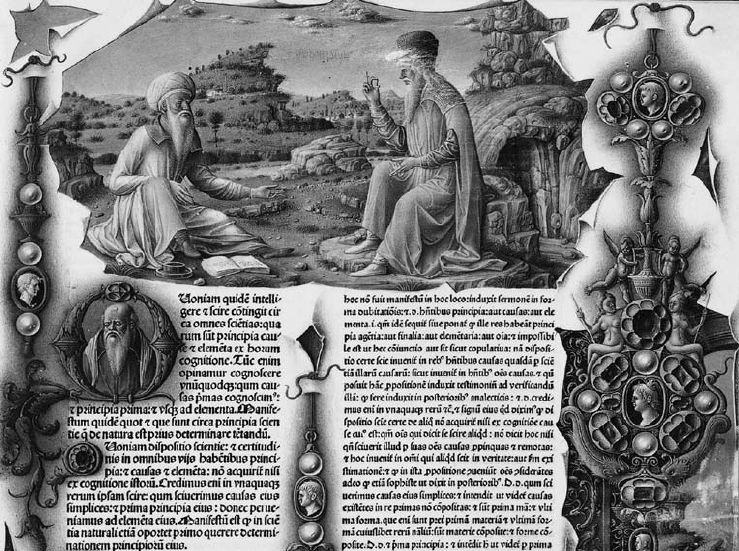

Plato’s vision of the soul as charioteer, as illustrated by Donatello in a medallion on a

portrait bust

238

SOUL AND MIND

the age of discretion. Since anger can conXict with reason and appetite, we

have to attribute it to a third element in the soul, which we can call temper

(to thymoeides; 441b). Justice in the soul is the harmony of these three

elements.

We meet the tripartite soul again in book 9 of the Republic. The lowest

element in it can be called the avaricious element, since money is the

principal means of satisfying the desires of appetite. Temper seeks power,

victory, and repute, and so may be called the honour-loving or ambitious

part of the soul. Reason pursues knowledge of truth: its love is learning. In

each man’s soul one or other of these elements may be dominant: he can

be classed accordingly as avaricious, ambitious, or academic. Each type of

person will claim their own life is the best life: the avaricious man will

praise the life of business, the ambitious man will praise a political career,

and the academic man will praise knowledge and understanding and the

life of learning. Naturally, Plato awards the palm to the philosopher: he has

the broadest experience and the soundest judgement, and the objects to

which he devotes his life are much more real than the illusory pleasures

pursued by his competitors (587a).

There are diVerences, it will be seen, between the accounts of the soul in

book 4 and in book 9. In the me antime Plato has introduced the Theory of

Ideas and has set out his plan of education for philosopher kings. Reason’s

task is no longer just to take care of the body: it is exercised in the

ascending scale of mental states and activities described in the Line: im-

agination, belief, and knowledge. At the end of book 9 we bid farewell to

the tripartite soul with a vivid picture. Appetite is a many-headed beast,

constantly sprouting heads of tame and wild animals; temper is like a lion,

and reason like a man. The beast is larger than the other two, and all three

are stowed away within a human being. We have come a long way from the

humble spider of Heraclitus.

The tripartite soul is not Plato’s last word in the Republic. In book 10 he

makes a contrast between diVerent elements in the reasoning part: one that

is confused by optical illusions, and another that measures, counts, and

weighs. Whereas in the earlier books the parts of the soul were distin-

guished by their desires, we now have a diVerence of cognitive power

presented as a basis for distinguishing parts.

In the same book Socrates oVers a new proof of immortality. Each thing

is destroyed by its characteristic disease: eyes by ophthalmia, and iron by

239

SOUL AND MIND

rust. Vice is the characteristic disease of the soul: but it does not destroy the

soul. If the soul ’s own disease cannot kill it, then it cannot be killed by

bodily disease and must be immortal (609d ). But what is immortal cannot

be an uneasily composite entity like the threefold soul. Such a soul is like a

statue in the sea covered with barnacles. The element of the soul that loves

wisdom and has a passion for the divine must be stripped of extraneous

elements if we are to see it in all its loveliness. Whether the soul seen in its

true nature would prove manifold or simple is left an open question

(611b V., 612a3).

In the Timaeus, however, the tripartite soul reappears, and its parts are

given corporeal locations. Reason sits in the head, the other two parts are

placed in the body, with the neck as an isthmus to keep the divine and the

mortal elements of the soul apart from each other. Temper is located

around the heart, and appetite in the belly, with the midriV separating the

two like the partition between the men’s and women’s quarters in a house.

The heart is the guardroom from which commands can be transmitted

around the body, via the circulating blood, when reason for some purpose

or other orders combat stations. The lowest part of the soul is kept under

control by the liver, which is particularly susceptible to the inXuence of

mind. The coiling of the bowels has the function of preventing appetites

from becoming insatiable (69c–73b).

Plato on Sense-Perception

While the Timaeus, like the earlier books of the Republic, anatomizes the soul

on the basis of desire rather than cognit ion, the dialogue does deal at some

length with the mechanisms of perception. The status of sense-perception

also attracted Plato’s attention in the Theaetetus in the course of the discus-

sion of Protagoras’ thesis that whatever seems to a particular person is true

for that person. Behind Protagoras Plato detects Heraclitus’ doctrine of

universal X ux.

If everything in the world is in constant change, then the colours we see

and the qualities we detect with our other senses cannot be stable, objective

realities. Rather, each of them is a meeting between one of our senses

and some appropriate transitory item in the universal maelstrom.

When the eye, for instance, comes into contact with a suitable visible

240

SOUL AND MIND

counterpart, the eye begins to see whiteness, and the object begins to look

white. The whiteness itself is generated by the intercourse between these

two parents, the eye and the object. The eye and its object are themselves

subject to perpetual change, but their motion is slow by comparison with

the speed with which the sense-impressions come and go. The eye’s seeing

of the white object, and the whiteness of the object itself, are two twins

which are born and can die together (156a–157b).

A similar tale can be told of other senses: but it is not clear how seriously

Plato means us to take this account of sensation. It occurs, after all, in the

course of a reductio ad absurdum argument against the Heraclitean thesis that

everything is always changing both in quality and in place. If something

stayed put, Socrates argues, we could describe how it looked, and if we had

a patch of constant colour, we could describe how it moved from place to

place. But if both kinds of change are taking place simultaneously, we are

reduced to speechlessness: we cannot say what is moving, or what is changing

colour. Each episode of seeing will turn instantly into an episode of non-

seeing, and perception becomes impossible (182b–e).

Nonetheless, the principle that seeing is an encounter between eye and

object is stated by Plato on his own account in the Timaeus and an explan-

ation is there oVered of the mechanism of vision. Within our heads there is

a gentle Wre, akin to daylight: this Wre Xows through our eyes and makes a

uniform column with the surrounding light: when this strikes an object,

shivers are sent back along the column, through the eyes, and into the

body to produce the sensation we call sight (45d). Colours are a kind of

Xame that streams oV bodies and is composed of particles so proportioned

to our sight as to yield sensation. These Xames travel towards the eye using

the original light column as a kind of carrier wave. Individual colours are

the product of diVerent mixtures of particles of four basic kinds: black,

white, red, and bright (67b–68d).

Aristotle’s Philosophical Psychology

Plato’s philosophy of mind has to be pieced together from fragments of

various dialogues, largely concerned with ethical and metaphysical issues.

The case is very diVerent when we come to Aristotle’s philosophical

psychology. Here, in addition to m aterial from ethical writings, we have

241

SOUL AND MIND

a systematic treatise on the nature of the soul (de Anima) and a number of

minor monographs on topics such as sense-perception, memory, sleep, and

dreams. Aristotle took over and developed some of Plato’s ideas, such as the

division of the soul into parts and faculties and the philosophical anal ysis of

sensation as encounter, but his fundamental approach diVers by being

rooted in the study of biology. The way in which he structured the soul

and its faculties inXuenced not only philosophy but science for nearly two

millennia.

For Aristotle the biologist the soul is not, as in the Phaedo, an exile from a

better world ill-housed in a base body. The soul’s very essence is deWned by

its relationship to an organic structure. Not only humans, but beasts and

plants have souls—not second-hand souls, transmigrants paying the pen-

alty of earlier misdeeds, but intrinsic principles of animal and veget able life.

A soul, Aristotle says, is ‘the actuality of a body that has life’, where life

means the capacity for self-sustenance, growth, and decay. If we regard a

living substance as a composite of matter and form, then the soul is the

form of a natural, or as Aristotle sometimes says, organic, body (de An. 2.1.

412a20,b5–6).

Aristotle gives several deWnitions of ‘soul’ which have seemed to some

scholars inconsistent with each other.1 But the diVerences between the

deWnitions arise not from an incoherent notion of soul, but from an

ambiguity in Aristotle’s use of the Greek word for ‘body’. Sometimes the

word means the living compound substance: in that sense, the soul is

the form of a body that is alive, a self-moving body (2.1. 412b17). Sometimes

the word means the appropriate kind of matter to be informed by a soul: in

that sense, the soul is the form of a body that potentially has life (2. 1. 412a22;

2. 2. 414a15–29). The soul is the form of an organic body, a body that has

organs, that is to say parts which have speciWc functions, such as the

mouths of mammals and the roots of trees.

The Greek word ‘organon’ means a tool, and Aristotle illustrates his

notion of soul by comparison both with inanimate tools and with bodily

organs. If an axe were a living body, its power to cut would be its soul; if an

eye were a whole animal, its power to see would be its soul. A soul is an

actuality, Aristotle tells us, but he makes a distinction between Wrst and

1 On this see J. Barnes, ‘Aristotle’s Concept of Mind’ (Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society (1972),

101–14); J. L. Ackrill, ‘Aristotle’s DeWnitions of Psyche’(Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society (1973), 119.

242

SOUL AND MIND

second actuality. When the axe is actually cutting, and the eye is actually

seeing, that is second actuality. But an axe in a sheath, and the eye of a

sleeper, retain a power that they are not actually exercising: that active

power is a Wrst actuality. It is that kind of actuality that the soul is: the Wrst

actuality of a living body. The exercise of this actuality is the totality of the

vital operations of the organism (2. 1. 412b11–413a3).

The soul is not only the form, or formal cause, of the living body: it is

also the origin of change and motion in the body, and above all it is also the

Wnal cause that gives the body its teleological orientation. Reproduction is

one of the most fundamental vital operations. Each living thing strives ‘to

reproduce its kind, an animal producing an animal, and a plant a plant, in

order that they may have a share in the everlasting and the divine so far as

they can’ (2. 4. 415a26–9, b16–20).

The souls of living beings can be ordered in a hierarchy. Plants have a

vegetative or nutritive soul, which consists of the powers of growth,

nutrition, and reproduction (2. 4. 415a23–6). Animals have in addition the

powers of perception, and locomotion: they possess a sensitive soul, and

every animal has at least one sense-faculty, touch being the most universal.

Whatever can feel at all can feel pleasure: and hence animals, who have

senses, also have desires. Humans in addition have the power of reason and

thought (logismos kai dianoia), which we may call a rational soul.

Aristotle’s theoretical concept of soul diVers from that of Plato before

him and Descartes after him. A soul, for him, is not an interior, immaterial

agent acting on a body. ‘We should not a sk whether body and soul are one

thing, any more than we should ask that question about the wax and the

seal imprinted on it, or about the matter of anything and that of which it is

the matter’ (2. 1. 412b6–7). A soul need not have parts in the way that a

body does: perhaps they are no more distinct than concave and convex in

the circumference of a circle (NE 1. 13. 1102a30–2). When we talk of parts of

the soul we are talking of faculties: and these are distinguished from each

other by their operations and their objects. The power of growth is distinct

from the power of sensation because growing and feeling are two diVerent

activities; and the sense of sight diVers from the sense of hearing not

because eyes are diVerent from ears, but because colours are diVerent

from sounds (de An.2.4.415a14–24).

The objects of sense come in two kinds: those that are proper to

particular senses, such as colour, sound, taste, and smell, and those that

243

SOUL AND MIND

are perceptible by more than one sense, such as motion, number, shape,

and size. You can tell, for instance, if something is moving either by

watching it or by feeling it, and so motion is a ‘common sensible’ (2. 6.

418a7–20). We do not have a special organ for detecting common sensibles,

but Aristotle says that we do have a faculty which he calls koine aisthesis,

literally ‘common sense’, but better translated, because of English idiom,

‘general sense’ (3.1. 425a27). When we encounter a horse, we may see, hear,

feel, and smell it: it is the general sense that uniWes these as perceptions of a

single object (though the knowledge that this object is a horse is, for

Aristotle, a function of intellect rather than sense). The general sense is

given by Aristotle several other functions: for instance, it is by the general

sense that we perceive that we are using the particular senses (3. 1.

425b13 V.), and it is by the general sense that we tell the diVerence between

sense objects proper to diV erent senses (e.g. between white and sweet) (3. 4.

429b16–19). This last move seems ill-judged: telling the diVerence between

white and sweet is surely not an act of sensory discrimination like telling

the diVerence between red and pink. What would it be like to mistake

white for sweet?

Aristotle’s most interesting thesis about the operation of the individual

senses is that a sense-faculty in operation is identical with a sense-object in

action: the actuality of the sense-object is one and the same as the actuality

of the sense-faculty (3. 2. 425b26–7, 426a16). Aristotle explains his thesis by

using sound and hearing as an example; because of diVerences between

Greek and English idiom I will try to explain what he means in the case of

the sense of taste.2 The sweetness of a cup of tea is a sense-object, something

that can be tasted. My ability to taste is a sense-faculty. The operation of the

sense of taste upon the object of taste is the same thing as the action of

the object upon my sense. That is to say, the tea’s tasting sweet to me is one

and the same event as my tasting the sweetness of the tea.

Aristotle is applying to the case of sensation his scheme of layers of

potentiality and actuality (2. 5. 417a22–30, b28–418a6). The tea is actually

sweet, whereas before the sugar was put in, it was only potentially sweet.

The sweetness of the tea in the cup is a Wrst actuality: the tea’s actually

tasting sweet to me is a second actuality. Sweetness is nothing other than

2 Aristotle complains that Greek lacks a word for what an object does to us when we taste it

(3. 2. 426a17). English does not, but it does lack a single word corresponding to the Greek word

for what a sound does to us when it makes us hear it.

244

SOUL AND MIND

the power to taste sweet to suitable tasters; and the faculty of taste is

nothing other than the power to taste such things as the sweetness of sweet

objects. Thus we can agree that the sensible property in operation is the

same thing as the faculty in operation, though of course the power to taste

and the power to be tasted are two diVerent things, one in an animal and

the other in a substance.

This seems a sound and important philosophical analysis of the concept of

sensation: it enables one to dispense with the notion, which has misled many

philosophers, that sensation involves a transaction between the mind and

some representation of what is sensed. Aristotle’s detailed explanations of the

chemical vehicles of sensory properties and the mechanism of the organs of

sensation are very diVerent matters, speculative theories long since super-

annuated. Though Aristotle is very critical of his predecessors in this area,

such as Democritus and the Plato of the Timaeus, his own accounts are no less

distant than theirs from the truth as discovered by the progress of science.

Besides the Wve senses and the general sense, Aristotle recognizes other

faculties which later came to be grouped together as the ‘inner senses’:

notably imagination (phantasia)(de An. 3. 3. 427b28–429a9), and memory, to

which he devoted an entire opuscule (de Memoria). Corresponding to the

senses at the cognitive level, there is an aVective part of the soul, the locus of

spontaneous felt emotion. This is introduced in the Nicomachean Ethics as part

of the soul that is basically irrational but which is, unlike the vegetative

soul, capable of being controlled by the reason. It is the part of the soul for

desire and passion, corresponding to appetite and temper in the Platonic

tripartite soul. When brought under the sway of reason it is the home of the

moral virtues such as courage and temperance (1. 13. 1102a26–1103a3).

For Aristotle as for Plato the highest part of the soul is occupied by mind

or reason, the locus of thought and understanding. Thought di Vers from

sense-perception, and is restricted—on earth at least—to human beings (de

An.3.3.427a18–b8). Thought, like sensation, is a matter of making judge-

ments; but sensation concerns particulars, while intellectual knowledge is

of universals (2. 5. 417b23). Aristotle makes a distinction between practical

reasoning and theoretical reasoning, and makes a corresponding division of

faculties within the mind. There is a deliberative part of the rational soul

(logistikon) which is concerned with human aVairs, and there is a scientiWc

part (epistemonikon) that is concerned with eternal truths (NE 6. 1. 1139a16; 12.

1144a2–3). This distinction is easy enough to understand; but in a famous

245

SOUL AND MIND

passage of the de Anima Aristotle introduces a diVerent distinction between

two kinds of mind (nous) which is very diYcult to grasp. Everywhere in

nature, he says, we Wnd a material element, which is potentially anything

and everything, and there is also a c reative element that works upon the

matter. So it is too with mind.

There is a mind of such a kind as to become everything, and another for making

all things, a positive state like light—for in a certain manner light makes potential

colours into actual colours. This mind is separable, impassible, and unmixed, being

in essence actuality; for the agent is always superior to the patient, and the

principle to the matter. Knowledge in actuality is the very same thing as the

object of knowledge. (de An.3.5.430a14–21)

In antiquity and the Middle Ages this passage was the subject of sharply

diVerent interpretations. Some—particularly among Arabic commenta-

The foremost Arabic interpeter of Aristotle, Averroes, is here represented by a

sixteenth-century illuminator of his commentary as receiving instruction from the

Philosopher

246

SOUL AND MIND

tors—identiWed the separable, active agent, the light of the mind, with God

or with some other superhuman intelligen ce. Others—particularly among

Latin commentators—took Aristotle to be identifying two diVerent facul-

ties within the human mind: an active intellect, which formed concepts,

and a passive intellect, which was a storehouse of ideas and beliefs.

The theorem of the identit y in actuality of knowledge and its object—

parallel to the corresponding thesis about sense-perception—was under-

stood, on the second interpretation, in the following manner. The objects

we encounter in experience are only potentially, not actually, thinkable,

just as colours in the dark are only potentially, not actually, visible. The

active intellect creates concepts—actually thinkable objects—by abstract-

ing universal forms from particular experience. These matterless forms

exist only in the mind: their actuality is simply to be thought. Thinking

itself consists of nothing else but being busy about such universals. Thus

the actualization of the object of thought, and the operation of the thinker

of the thought, are one and the same.

If the second interpretation is correct, then Aristotle is here recognizing

a part of the human soul that is separable from the body and immortal. In

a similar vein, in the Generation of Animals (2. 3. 736b27) Aristotle says that

reason enters the body ‘from out of doors’, being the sole divine element in

the soul and being unconnected with any bodily activity. These passages

remind us that in addition to the oYcial, biological notion of the soul that

we have been studying, there is detectable from time to time in Aristotle a

Platonic residue of thought according to which the intellect is a distinct

entity separable from the body.

This line of thought is nowhere more prominent than in the Wnal book

of the Nicomachean Ethics. Whereas in the Eudemian Ethics and in the books that

are common to the two treatises, the theoretical intellect is clearly a faculty

of the soul, and there is no suggestion that it is transcendent or immortal, in

book 10 of the Nicomachean Ethics the life of intellect is described as super-

human and is contrasted with that of the syntheton, or body–soul compound.

The moral virtues and practical wisdom are virtues of the compound, but

the excellence of intellect is capable of separate existence (10. 7. 1177a14,

b26–9; 1178a14–20). It is in this activity of the separable intellect that, for the

Nicomachean Ethics, human happiness supremely consists.

It is diYcult to reconci le the biological and the transcendent strains

in Aristotle’s thought. No theory of chronological development has

247

SOUL AND MIND