Kenny Anthony. Ancient Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy Volume 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

assigning to it its ultimate principles of explanation. Thus Aristotle’s

Wrst philosophy is both the science of Being qua being, and also

theology.

Epicureans and Stoics devoted little attention to the ontological questions

that preoccupied Plato and Aristotle. One development, however, deserves

a brief remark.

In one of his letters Seneca writes to explain to a friend how things are

classiWed by species and genus: man is a species of animal, but above the

genus animal there is the genus body, since some bodies are animate and

others (e.g. rocks) are not. Is there a genus above body? Yes: there is the

genus of what there is (quod est): for of the things there are, some are bodily

and some are not. This, according to Seneca, is the supreme genus.

The Stoics want to place above this yet another, more primary genus. To these

Stoics the primary genus seems to be ‘something’—let me explain why. In nature,

they say, some things are and some things are not, and nature includes even those

things that are not—things that enter the mind, like Centaurs, giants and

whatever other delusory Wctions take on an image although they lack substance.

(Ep. 58. 11–15)

Here, we can see clearly identiWed a use of the verb ‘to be’ in the sense of

‘exist’ without any of the complications dating from Parmenides.4 This is a

great advance. On the other hand, in treating the existent and the non-

existent as two species of a single supreme ontological genus, namely

‘something’ (ti, quid ), the Stoics sowed the seed of centuries of philosophical

confusion. We shall meet the fruits of this confusion in later volumes. Its

most elaborate product is the ontological argument for the existence of

God; its most fashionable oVspring is the distinction between worlds that

are actual and worlds that are possible.

Despite the signiWcance of this Stoic development, it is not until we

come to the Neoplatonists that metaphys ics resumes its importance in the

ancient world as the prime element of philosophy. But in an author such

as Plotinus, metaphysics has taken such a theological turn that his teaching

is best considered in Chapter 9 devoted to the philosophy of religion.

4 See LS i. 163.

228

METAPHYSICS

7

Soul and Mind

T

he soul is much older than philosophy. In many places and in many

cultures human beings have imagined themselves surviving death,

and the ancient equivalents of the world ‘soul’ Wrst appear as an expression

for whatever in us is immortal. Once philosophy began, the possibility of an

afterlife and the nature of the soul came to be one of its central concerns,

straddling the boundary between religion and science.

Pythagoras’ Metempsychosis

Pythagoras, often venerated as the Wrst of philosophers, was also renowned

as a champion of survival after death. He did not, however, believe as many

others have done that at death the soul entered a diVerent and shadowy

world; he believed that it returned to the world we all live in, but it did so

as the soul of a diVerent body. He himself claimed to have inherited his soul

from a distinguished line of spiritual ancestors, and reported that he could

remember Wghting, some centuries earlier, as a hero at the siege of Troy.

Such transmigration (which need not continue for ever) was quite diVer-

ent from the blessed immortality of the gods, altogether exempt from

death (D.L. 8. 45).

Souls could transmigrate in this way, according to Pythagoras, not only

between one human and another, but also across species. He once stopped

a man whipping a puppy because he claimed to have recognized in its

whimper the voice of a dead friend (D.L. 8. 36). Shakespeare was struck by

this doctrine, and refers to it several times. Malvolio, catechized about

Pythagoras in Twelfth Night, tells us that his belief was

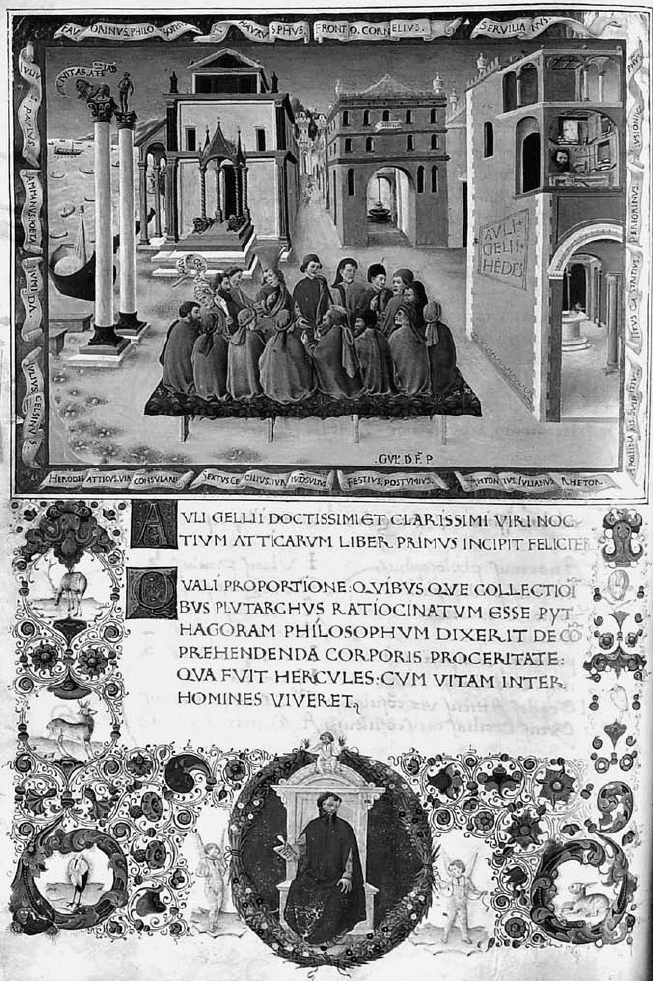

Pythagoras calculating for his disciples the height of long-dead Hercules (from a

Wfteenth-century manuscript of Aulus Gellius)

That the soul of our grandam might haply inhabit a bird.

(iv. ii. 50–1)

And when Shylock is abused in The Merchant of Venice, the possibility is raised

of migration in the reverse direction.

Thou almost mak’st me waver in my faith

To hold opinion with Pythagoras

That souls of animals infuse themselves

Into the trunks of men. (iv. i. 130–3)

Pythagoras did not o Ver philosophical arguments for survival and transmi-

gration; instead he claimed to prove it in his own case by identifying his

belongings in a previous incarnation. He was thus the Wrst of a long line of

philosophers to take memory as a criterion of personal identity (Diodorus

10. 6. 2). His contemporary Alcmaeon seems to have been the Wrst to oVer a

philosophical argument in this area, claiming, by a dubious inference from

an obscure premiss, that the soul must be immortal because it is in

perpetual motion like the divine bodies of the heavens (Aristotle, de An.

1. 2. 405a29–b1).

Empedocles adopted an elaborate version of Pythagorean transmigration

as part of his cyclical conception of history. As a result of a primeval fall,

sinners such as murderers and perjurers survive as wandering spirits for

thrice ten thousand years, incarnate in many diVerent forms, exchanging

one hard life for another (DK 31 B115). Since the bodies of animals are thus

the dwelling places of punished souls, Empedocles told his followers to

abstain from eating living things. In slaughtering an animal you might

even be attacking your own son or mother (DK 31 B137). Moreover,

transmigration is possible not only into animals but also into plants, so

even vegetarians should be careful what they eat, avoiding in particular

beans and laurels (DK 31 B141). After death, if you had to be an animal, it

was best to become a lion; if a plant, best to become a laurel. Empedocles

himself claimed to have experienced transmigration not only as a human

but also in the vegetable and animal realm.

I was once in the past a boy, once a girl, once a tree,

Once too a bird, and a silent Wsh in the sea.

(DK 31 B117)

231

SOUL AND MIND

In this early period, inquiry into the nature of the soul in the present life

seems to have been subsequent to speculation on its location in an afterlife.

All the earliest thinkers seem to have taken a materialist view: the soul

consisted either in air (Anaximenes and Anax imander) or Wre (Parmenides

and Heraclitus). It took some time, however, for the problem to be

addressed: how does a material element, however Wne and Xuid, perform

the soul’s characteristic functions of feeling and thought?

Heraclitus oVers only a splendid simile:

As a spider in the middle of its web notices as soon as a Xy damages any of its

threads, and rushes thither as though grieving for the breaking of the thread, so a

person’s soul, if any part of the body is hurt, hurries quickly thither as if unable to

bear the hurt of the body to which it is tightly and harmoniously joined. (DK 22

B67a)

This paragraph is the ancestor of m any philosophical attempts to explain

the capacities and behaviour of humans as the activities of a tiny animal

within—though later philosophers were more inclined to view the soul as

an internal homunculus than as an internal arthropod.

Perception and Thought

Empedocles was the Wrst philosopher to oVer a detailed account of

how perception takes place. Like his predecessors he was a materialist.

The soul, like everything else in the universe, was a compound of earth, air,

Wre, and water. Sensation takes place by a matching of each of these

elements, as they occur in the objects of perception, with their counter-

parts in our sense-organs. Strife and Love, the forces that in Empedocles’

system operate upon the elements, also have their part in this matching

procedure, which is governed by the principle that like is perceived

by like.

We see the earth by earth, by water water see,

The air of the sky by air, by Wre the Wre in Xame,

Love we perceive by love, strife by sad strife, the same.

(DK 31 B109)

The process seems to take place like this. Objects in the world give oV an

eZuence that reaches the pores of our eyes; sound is an eZuence that

232

SOUL AND MIND

penetrates our ears. If perception is to take place, the pores and the

eZuences have to match each other (DK 31 A86). This matching must,

of course, take place at the level of the elements, the fundamental

principles of explanation in Empedocles’ system. In some cases this is

simple: sound is carried by air, which is echoed by the air in the inner

ear. In the case of sight it is more complicated, and must be a matter of the

proportions of each of the elements, as suggested in the fragment above.

The most complex mixture of all the elements is blood, and as the blood

churns round the heart this produces thought. The reWned nature of the

blood’s constitution is what explains the wide-ranging nature of thought

(DK 31 B105, 107).

The crude nature of Empedocles’ materialism made him easy game for

later philosophers of mind. Aristotle complained that he had not distin-

guished between perception and thought. Others pointed out that other

things besides eyes and ears had pores: why then were sponges and

pumices not capable of perception? The atomist Democritus oVered an

answer to this question. The visual image was the product of an

interaction between eZuences from the seen object and eZuences

from the person seeing: this image or impression was formed in the

intervening air, and then entered the pupil of the eye (KRS 589). But

Democritus, like Empedocl es, was unable to oVer any remotely convin-

cing account of thought, and so, like him, fell foul of Aristotle’s

criticism.

The Presocratic whom later Greeks revered as a philosopher of mind was

Anaxagoras. Anaxagoras believed that the universe began as a tiny complex

unit which expanded and evolved into the world we know, but that at

every stage of evolution every single thing contains a portion of everything

else. This development is presided over by Mind (nous), which is itself

outside the evolutionary process.

Other things have a portion of everything, but Mind is unlimited and independent

and is unmixed with any kind of stuV, but stands all alone by itself. For if it was not

by itself, but was mixed with anything else, it would have a share in every kind of

stuV, since as I said earlier in everything there is a portion of everything. The

things mixed with it would prevent it from controlling everything in the way it

does now when it is alone by itself. For it is the Wnest and purest of all things, and it

has all knowledge of and all power over everything. All things that have souls, the

greater and the lesser, are governed by Mind. (KRS 476)

233

SOUL AND MIND

Anaxagoras distinguishes between souls, which are part of the material

world, and a godlike Mind, which is immaterial, or at least is made of a

unique, ethereal, kind of matter. Whereas for Empedocles like was known

by like, Anaxagoras’ Mind can know everything only because it is unlike

anything. There is not only the one grand cosmic Mind: some other things

(presumably humans) have a share in mind, so that there are lesser minds

as well as greater (KRS 476, 482).

Immortality in Plato’s Phaedo

Among those inXuenced by Anaxagoras was Socrates; but it is diYcult to be

sure what the historic Socrates truly thought about the soul and the mind.

Socrates in Plato’s Apology appears to be agnostic about the possibility of an

afterlife. Is death, he wonders, a dreamless sleep or is it a journey to another

world to meet the glorious dead? ‘We go our ways, I to die and you to live:

which is better, only God knows’ (40c–42a). The Platonic Socrates in the

Phaedo, however, is a most articulate protagonist of the thesis that the soul

not only survives death, but is better oV after death (63e).

The starting point of his discussion is the conception of a human being

as a soul imprisoned in a body. True philosophers care little for bodily

pleasures such as food and drink and sex, and they Wnd the body a

hindrance rather than a help in philosophic pursuits (64c–65c). ‘Thought

is best when the mind is gathered into itself, and none of these things

trouble it—neither sounds nor sights nor pain, nor again any pleasure—

when it takes leave of the body and has as little as possible to do with it’

(65c). So philosophers in pursuit of truth keep their souls detached from

their bodies. But death is the separation of soul from body: hence a true

philosopher has throughout his life in eVect been craving for death (67e).

Socrates’ interlocutors, Simmias and Cebes, Wnd his words edifying: but

Cebes feels obliged to point out that most people will reject the idea that

the soul can survive the body. They believe that at death the soul ceases to

exist, vanishing into nothingness like a puV of smo ke (70a). Socrates agrees

that he needs to oVer proofs that after a man’s death his soul still exists.

First he oVers an argument from opposites. If two things are opposites,

each of them comes from the other. If you go to sleep, you must have been

awake; if you wake up, you must have been asleep. If A becomes larger than

234

SOUL AND MIND

B, A must have been smaller than B; if A becomes better than B, A must

have been worse than B. So opposites like larger and smaller, better and worse,

come into being from each other. But death and life are opposites, and the

same holds here. If death comes from life, must not life in turn come from

death? Since life after death is not visible, it must be in another world

(70c–72e).

Socrates’ next argument sets out to prove the existence of a non-

embodied soul not after, but before, its life in the body. He argues Wrst

that knowledge is recollection, and then that recollect ion involves pre-

existence. We often see things, he says, that are more or less equal in size;

but we never see any two things in the world absolutely equal to each

other. Our idea of equality, therefore, cannot be derived from experience.

The approximately equal things we see are simply reminders of an absolute

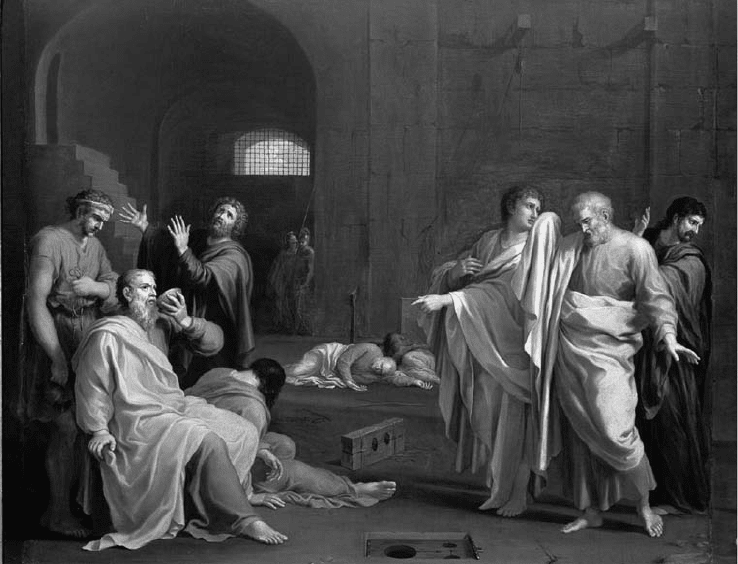

The death of Socrates has been the subject of many paintings. This one in the Uffizi is

by Claude Dufresnoy (1611–68).

235

SOUL AND MIND

equality we have encountered earlier. But this encounter did not take place

in our present life, nor by means of the senses: it must have taken place in a

previous life and by the operation of pure intellect. What goes for the Idea

of absolute equality must work also for other similar Ideas, like absolute

goodness and absolute beauty (73a–77d).

Thirdly, Socrates argues from the concepts of dissolubility and indissolu-

bility. Whatever can disintegrate, as the body does at death, must

be composite and changeable. But the Ideas with which the soul is

concerned are unchangeable, unlike the visible and fading beauties we

see with our eyes. Within the visible world of Xux, the soul staggers like

a drunkard; it is only when it returns within itself that it passes into the

world of purity, eternity, and immortality in which it is at home. If even

bodies, when mummiWed in Egypt, can survive for many years, it is hardly

credible that the soul dissolves at the moment of death. Instead, provided it

is a soul puriWed by philosophy, it will depart to an invisible world of bliss

(78b–81a).

In response to these arguments, Simmias oVers a diVerent conception of

the soul. Consider, he says, a lyre made out of wood and strings, which is

tuned by the tension of the strings. A living human body may be compared

to a lyre in tune, and a dead body to a lyre out of tune. It would be absurd

to argue that because attunement is not a material thing like wood and

strings, it could survive the smashing of the lyre. W hen the strings of the

body lose their tone through injury or disease, the soul must perish like the

tunefulness of a br oken lyre (84c–86e).

Cebes, too, has an objection to make. He agrees that the soul is tougher

than the body and need not come to an end when the body does; in the

normal course of life, the body suVers frequent wear and tear and needs

constant repair by the soul. But a soul might be immortal, in the sense that

it can survive death, without being imperishable, in the sense that it will

live for ever. Even if it transmigrates from body to body, perhaps one day it

will pass away, just as a weaver, who has made and worn out many coats in

his lifetime, one day meets his death and leaves a coat behind (86e–88b).

Socrates produces several reasons for rejecting Simmias’ analogy. Being

in tune admits of degrees; but no soul can be more or less a soul than

another. It is the tension of the strings that causes the lyre to be in tune,

but in the human case the relationship goes in the other direction: it is the

soul that keeps the body in order (92a–95e).

236

SOUL AND MIND

In response to Cebes, Socrates introduces a distinction between what

later philosophers would call the necessary and contingent properties of

things. Human beings may or may not be tall: tallness is a contingent

property of humans. The number three, however, cannot but be odd, and

snow cannot but be cold: these properties are necessary to them and not

just contingent. Coldness cannot turn into heat, and consequently snow,

which is necessarily cold, must either retire or perish at the approach of

heat (103a–105c).

We can generalize: not only will opposites not receive opposites, but

nothing that necessarily brings with it an opposite will adm it the opposi te

of what it brings. Now the soul brings life, just as snow brings cold. But

death is the opposite of life, so that the soul can no more admit death than

snow can admit heat. But what cannot admit death is immortal, and so the

soul is immortal. Unlike the snow, it does not perish, but retires to another

world (105c–107a).

Socrates’ arguments convince Simmias and Cebes in the dialogue, but

surely they should not have done so. Is it true that opposites always come

from opposites? And even when opposites do come from opposites, must

the cycle continue for ever? Even if sleeping has to follow waking, may not

one last waking be followed (as the Socrates of the Apology surmised) by

everlasting sleep? And however true it may be that the soul cannot abide

death, why must it retire elsewhere when the body dies, rather than perish

like the melted snow?

The Anatomy of the Soul

In the Phaedo the soul is treated as a single, uniWed entity. Elsewhere, Plato

oVers us account s of the soul in which it has diVerent parts with diVerent

functions. In the Phaedrus, having oVered a brief proof, reminiscent of

Alcmaeon, that soul must be immortal because it is self-moving, Plato

turns to describing its structure. Think of it, he says, as a triad: a charioteer

with a pair of horses, one good and one bad, driving towards a heavenly

banquet (246b). The good horse strives upwards, while the bad horse

constantly pulls the chariot downwards. The horses are clearly meant to

represent two diVerent parts of the soul, but their exact functions are never

made clear. Plato applies his analogy mainly in the course of setting out the

237

SOUL AND MIND