Kenny Anthony. Ancient Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy Volume 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

These qualiWcations mean that Epicurus’ hedonism is far from being an

invitation to lead the life of a voluptuary. It is not drinking and carousing,

nor tables laden with delicacies , nor promiscuous intercourse with boys

and women, that produce the pleasant life, but sobriety, honour, justice,

and wisdom. (D.L. 10. 132) A simple vegetarian diet and the company of a

few friends in a modest garden sufWce for Epicurean happiness.

What enables Epicurus to combine theoretical hedonism wit h practical

asceticism is his understanding of pleasure as being essentially the satis-

faction of desire. The strongest and most fundamental of our desires is

the desire for the removal of pain (D.L. 10. 127). Hence, the mere absence

of pain is itself a fu ndamental pleasure (LS 21a). Among our desires some

are natural and some are futile, and it is the natural desires to which the

most important pleasures correspond. We have natural desires for the

removal of the painful states of hunger, thirst, and cold, and the satisfac-

tion of these desires is naturally pleasant. But there are two kinds

of pleasure involved, for which Epicurus framed technical terms: there

is the kinetic pleasure of quenching one’s thirst, and the static pleasure

that supervenes when one’s thirst has been quenched (LS 21q). Both

kinds of pleasure are natural: but among the kinetic pleasures some are

necessary (the pleasure in eating and drinking enough to satisfy hunger

and thirst) and others are unnecessary (the pleasures of the gourmet)

(LS 21i, j).

Unnecessary natural pleasures are not greater than, but merely vari-

ations on, necessary natural pleasures: hunger is the best sauce, and eating

simple food when hungry is pleasanter than stufWng oneself with luxuries

when satiated. But of all natural pleasures, it is the static pleasures that

really count. ‘The cry of the Xesh is not to be hungry, not to be thirsty, not

to be cold. Someone who is not any of these states, and has good hope of

remaining so, coul d rival even Zeus in happiness’ (LS 21g).

Sexual desires are classed by Epicurus as unnecessary, on the grounds

that their non-fulWlment is not accompanied by pain. This may be surpris-

ing, since unrequited love can cause anguish. But the intensity of such

desire, Epicurus claimed, was due not to the nature of sex but to the

romantic imagination of the lover (LS 21e). Epicurus was not opposed to

the ful Wlment of unnecessary natural desires, provided they did no harm—

which of course was to be measured by their capacity for producing pain

(LS 21f). Sexual pleasure, he said, could be taken in any way one wished,

278

ETHICS

provided one respected law and convention, distressed no one, and did

no damage to one’s body or one’s essential resources. However, these

qualiWcations added up to substantial constraint, and even when sex did

no harm, it did no good either (LS 21g).

Epicurus is more critical of the fulWlment of desires that are futile: these

are desires that are not natural and, like unnecessary natural desires, do not

cause pain if not fulWlled. Examples are the desire for wealth and the desire

for civic honours and acc laim (LS 21g, i). But so too are desires for the

pleasures of science and philosophy: ‘Hoi st sail’, he told a favourite pupil

‘and steer clear of all culture’ (D.L. 10. 5). Aristotle had made it a point in

favour of philosophy that its pleasures, unlike the pleasures of the senses,

were unmixed with pain (cf. NE 10. 7. 1177a25); now it is made a reason for

downgrading the pleasures of philosophy that there is no pain in being a

non-philosopher. For Epicurus the mind does play an important part in

the happy life: but its function is to anticipate and recollect the pleasures of

the senses (LS 21l, t).

On the basis of the surviving texts we can judge that Epicurus’ hedon-

ism, if philistine, is far from being licentious. But from time to time he

expressed himself in terms that were, perhaps deliberately, shocking to

many. ‘For my part I have no conception of the good if I take away the

pleasures of taste and sex and music and beauty’ (D.L. 10. 6). ‘The pleasure

of the stomach is the beginning and root of all good’ (LS 21m). Expressions

such as these laid the ground for his posthumous reputation as a gour-

mand and a libertine. The legend, indeed, was started in his lifetime by a

dissident pupil, Timocrates, who loved to tell stories of his midnight orgies

and twic e-daily vomitings (D.L. 10. 6–7).

More serious criticism focused on his teaching that the virtues were

merely means of securing pleasure. The Stoic Cleanthes used to ask his

pupils to imagine pleasure as a queen on a throne surrounded by the

virtues. On the Epicurean view of ethics, he said, these were handmaids

totally dedicated to her service, merely whispering warnings, from time to

time, against incautiously giving oVence or causing pain. Epicureans did

not demur: Diogenes of Oenoanda agreed with the Stoics that the virtues

were productive of happiness, but he denied that they were part of

happiness itself. Virtues were a means, not an end. ‘I afWrm now and

always, at the top of my voice, that for all, whether Greek or barbarian,

pleasure is the goal of the best way of life’ (LS 21p).

279

ETHICS

Stoic Ethics

In support of the central role they assigned to pleasure, Epicureans argued

that as soon as ever y animal was born it sought after pleasure and enjoyed

it as the greatest good while rejecting pain as the greatest evil. The Stoic

Chrysippus, on the contrary, argued that the Wrst impulse of an animal was

not towards pleasure, but towards self-preservation. Consciousness begins

with awareness of what the Stoics called, coining a new word, one’s own

constitution (LS 57a). An animal accepted what assisted, and rejected what

hampered, the development of this constitution: thus a baby would strive

Zeno and Epicurus (plus swine) represented on a silver cup from Boscoreale, first

century ad

280

ETHICS

to stand unsupported, even at the cost of falls and tears (Seneca, Ep. 121, 15

LS 57b). This drive towards the preservation and progress of the consti-

tution is something more primitive than the desire for pleasure, since it

occurs in plants as well as animals, and even in humans is often exercised

without consciousness (D.L. 8. 86 LS 57a). To care for one’s own consti-

tution is nature’s Wrst lesson.

Stoic ethics attaches great importance to Nature. Whereas Aristotle

spoke often of the nature of individual things and species, it is the Stoics

who were responsible for introducing the notion of ‘Nature’, with a capital

‘N’, as a single cosmic order exhibited in the structure and activities of

things of many diVerent kinds. According to Diogenes Laertius (D.L. 7. 87),

Zeno stated that the end of life was ‘to live in agreement with Nature.’

Nature teaches us to take care of ourselves through life, as our constit ution

changes from babyhood through youth to age; but self-love is not Nature’s

only teaching. Just as there is a natural impulse to procreate, there is a

natural impulse to take care of one’s oVspring; just as we have a natural

inclination to learn, so we have a natural inclination to share with others

the knowledge we acquire (Cicero, Fin.3.65LS57e). These impulses to

beneWt those nearest to us should, according to the Stoics, be extended

outward to the wider world.

Each of us, according to Hierocles, a Stoic of the time of Hadrian, stands

at the centre of a series of concentric circles. The W rst circle surrounding

my individual mind contains my body and its needs. The second contains

my immediate family, and the third and fourth contain extensions of my

family. Then come circles of neighbours, at varying distances, plus the circle

that contains all my co-nationals. The outermost and largest circle encom-

passes the whole human race. If I am virtuous I will try to draw these circles

closer together, treating cousins as if they were brothers, and constantly

transferring people from outer circles to inner ones (LS 57g).

The Stoics coined a special word for the process thus picturesquely

described: ‘oikeiosis’, literally ‘homiWcation’. A Stoic, adapting himself to

cosmic nature, is making himself at home in the world he lives in. Oikeiosis

is the converse of this: it is making other people at home with oneself,

taking them into one’s domestic circle. The universalism is impressive, but

its limitation s were soon noted. It is unrealistic to think that, how ever

virtuous, a person can bestow the same aVection on the most distant

foreigner as one can on one’s own family. Oikeiosis begins at home, and

281

ETHICS

even within the very Wrst circle we are more troubled by the loss of an eye

than by the loss of a nail. But if the benevolence of oikeiosis is not universally

uniform, it cannot provide a foundation for the obligation of justice to

treat all human beings equally (LS 57h). Moreover, the Stoics believed that

it was praiseworthy to die for one’s country: but is not that preferring an

outer circle to an inner one?

Again, the universe of nature contains more than the human beings

who inhabit the concentric circles: what is the right attitude to those who

share the cosmos with us? Stoics, in some moods, described the universe as

a city or state shared by men with gods, and it was to this that they

appealed in order to justify the self-sacriWce of the individual for the sake of

the community. In their practical ethical teaching there is little concern

with non-human agents. Animals, certainly, have no rights against man-

kind: Chrysippus was sure that humans can make beasts serve their needs

without violating justice (Cicero, Fin.3.67LS57g).

The cosmic order does, however, provide not only the context but

the model for human ethical behaviour. ‘Living in agreement with

nature’ does not mean only ‘living in accordance with human nature’.

Chrysippus said that we should live as taught by experience of natural

events, because our individual natures were part of the nature of the

universe. Consequently, Stoic teaching about the end of life can be

summed up thus:

We are to follow nature, living our lives in accordance with our own nature and

that of the cosmos, doing no act that is forbidden by the universal law, that is to

say the right reason that pervades all things, which is none other than Zeus, who

presides over the administration of all that exists. (D.L. 7. 87)

The life of a virtuous person will run tranquilly beneath the uniform

motion of the heavens, and the moral law within will mirror the starry

skies above.

Living in agreement with nature was, for the Stoics, equivalent to living

according to virtue. Their best-known, and most frequently criticized,

moral tenet was that virtue alone was necessary and sufWcient for happi-

ness. Virtue was not only the Wnal end and the supreme good: it was also

the only real good.

Among the things there are, some are good, some are evil, and some are neither

the one nor the other. The things that are good are the virtues: wisdom, justice,

282

ETHICS

fortitude, temperance, and so on. The things that are evil are the opposites of

these: folly, injustice, and so on. The things that are neither one nor the other are

all those things that neither help nor harm: for instance, life, health, pleasure,

beauty, strength, wealth, fame, good birth, and their opposites, death, disease,

pain, ugliness, weakness, poverty, disrepute, and low birth. (D.L. 7.101 LS 58a)

The items in the long list of ‘things that neither help nor harm’ were called

by the Stoics ‘indiVerent matters’ (adiaphora). The Stoics accepted that these

were not matters of indiVerence like whether the number of hairs on one’s

head was odd or even: they were matters that arous ed in people strong

desire and revulsion. But they were indiVerent in the sense that they were

irrelevant to a well-structured life: it was possible to be perfectly happy

with or without them (D.L. 7. 104–5 LS 58b–c).

Like the Stoics, Aristotle placed happiness in virtue and its exercise, and

counted fame and riches no part of the happiness of a happy person. But he

thought that it was a necessary condition for happiness to have a sufWcient

endowment of external goods (NE 1. 10. 1101a14–17; EE 1. 1. 1214b 16).

Moreover, he believed that even a virtuous man could cease to be happy

if disaster overtook himself and his family, as happened to Priam (NE 1. 10.

1101a8). By contrast, the Stoics, with the sole exception of Chrysippus,

thought that happiness, once possessed, could never be lost, and even

Chrysippus thought it could be terminated only by something like mad-

ness (D.L. 7. 127).

IndiVerent matters, the Stoics conceded, were not all on the same level

as each other. Some were popular (proegmena) and others unpopular (apo-

proegmena). More importantly, some went with nature and some went

against nature: those that went with nature had value (axia) and those

that went against nature had disvalue (apaxia). Among the things that have

value are talents and skills, health, beauty, and wealth; the opposites of

these have disvalue (D.L. 7. 105–6). It seems clear that, according to the

Stoics, all things that have value are also popular; it is not so clear whether

everything that is popular also has value. Virtue itself did not come within

the class of the popular, just as a king is not a nobleman like his courtiers,

but something superior to a nobleman (LS 58e). Chrysippus was willing to

allow that it was permissible, in ordinary usage, to call ‘good’ what strictly

was only popular (LS 58h); and in matters of practical choice between

indiVerent matters, the Stoics in eVect encouraged people to opt for the

popular (LS 58c).

283

ETHICS

An action may fall short of being a virtuous action (katorthoma) and yet be

a decent action (kathekon). An action is decent or Wtting if it is appropriate to

one’s nature and state of life (LS 59 b). It is decent to honour one’s parents

and one’s country, and the neglect of parents and failure to be patriotic is

something indecent. (Some things, like picking up a twig, or going into the

country, are neither decent nor indecent.) Virtuous actions are, a fortiori,

decent actions: what virtue adds to mere decency is Wrst of all purity of

motive and secondly stability in practice (LS 59g, h, i). Here Stoic doctrine

is close to Aristotle’s teaching that in order to act virtuously a person must

not only judge correctly what is to be done, but choose it for its own sake

and exhibit constancy of character (NE 2. 6. 1105a30–b1). Some actions,

according to the Stoics, are not only indecent but sinful (hamartemata) (LS

59m). The diVerence between these two kinds of badness is not made clear:

perhaps a Stoic sinner is like Aristotle’s intemperate man, while mere

indecency may be parallel to incontinence. For while the Stoics, implaus-

ibly, said that all sinful actions were equally bad, they did regard those that

arose from a hardened and incurable character as having badness of a

special kind (LS 59 o).

The Stoic account of incontinence, however, diVers from Aristotle in an

important respect. They regard it not as arising from a struggle between

diVerent parts of the soul but rather as the result of intellectual error.

Incontinence is the result of passion, which is irrational and unnatural

motion of the soul. Passions come in four kinds: fears, desires, pain, and

pleasure. According to Chrysippus passions were simply mistaken judge-

ments about good and evil; according to earlier Stoics they were perturb-

ations a rising from such mistaken judgements (LS 65 g, k). But all agreed

that the path of moral progress lay in the correction of the mistaken beliefs

(LS 65a, k). Because the beliefs are false, the passions must be eliminated,

not just moderated as on the Aristotelian model of the mean.

Desire is rooted in a mistaken belief that something is approaching that

will do us good; fear is rooted in a mistaken belief that something is

approaching that will do us harm. These beliefs are accompanied by a

further belief in the appropriateness of an emotional response, of yearning

or shrinking as the case may be. Since according to Stoic theory, nothing

can do us good except virtue, and nothing can do us harm except vice,

beliefs of the kind exhibited in desire and fear are always unjusti W ed, and

that is why the passions are to be eradicated. It is not that emotional

284

ETHICS

responses are always inappropriate: there can be legitimate joy and justiWed

apprehension. But if the responses are appropriate, then they do not count

as passions (LS 65f). Again, even the wise man is not exempt from irregular

bodily arousals of various kinds: but as long as he does not consent to

them, they are not passions (Seneca, de Ira 2. 3. 1).

When Chrysippus says that passions are beliefs, there is no need to regard

him as presenting the passions, implausibly, as calm intellectual assess-

ments: on the contrary he is pointing out that the assents to propositions

that set a high value on things are themselves tumultuous events. When

I lose a loved one, it appears to me that an irreplaceable value has left my life.

Full assent to this proposition involves violent internal upheaval. But if we

are ever to be happy, we must never allow ourselves to attach such supreme

value to anything that is outside our control.5

The weakness in the Stoic position is, in fact, its refusal to come to terms

with the fragility of happiness. We have met a parallel temptation in

classical epistemology: the refusal to come to terms with the fallibility of

judgement. The epistemological temptation is embodied in the fallacious

argument from ‘Necessarily, if I know that p, then p’ to ‘If I know that

p, then necessarily p’. The parallel temptation in ethics is to argue from

‘Necessarily, if I am happy, I have X’ to ‘If I am happy, I have X necessarily’.

This argument, if successful, leads to the denial that happiness can

be constituted by any contingent good that is capable of being lost (Cicero,

Tusc. 5. 41). Given the frail, contingent natures of human beings as we

know ourselves to be, the denial that contingent goods can constitute

happiness is tantamount to the claim that only superhuman beings can

be happy.

The Stoics in eVect accepted this conclusion, in their idealization of the

man of wisdom. Happiness lies in virtue, and there are no degrees of virtue,

so that a person is either perfectly virtuous or not virtuous at all. The m ost

perfect virtue is wisdom, and the wise man has all the virtues, since the

virtues are inseparable (LS 61f). Like Socrates, the Stoics thought of

the virtues as being sciences, and all of them as making up a single science

(LS 61h). One Stoic went so far as to say that to distinguish between

courage and justice was like regarding the faculty for seeing white as

diVerent from the faculty of seeing black (LS 61b). The wise man is totally

5 Here I am indebted to an unpublished paper by Martha Nussbaum.

285

ETHICS

free from passion, and is in possession of all worthwhile knowledge: his

virtue is the same as that of a god (LS 61j,63f).

The wise man whom we seek is the happy man who can think no human

experience painful enough to cast him down nor joyful enough to raise his spirits.

For what can seem important in human aVairs to one who is familiar with all

eternity and the vastness of the entire universe? (Cicero, Tusc. 4. 37).

The wise man is rich, and owns all things, since he alone knows how to use

things well; he alone is truly handsome, since the mind’s face is more

beautiful than the body’s; he alone is free, even if he is in prison, since he is

a slave to no appetite (Cicero, Fin 3. 75). It was unsurprising, after all this,

that the Stoics admitted that a wise man was harder to Wnd than a phoenix

(LS 61n). They thus purchase the invulnerability of happiness only at the

cost of making it unattainable.

Since a wise man is not to be found, and there are no degrees of virtue,

the whole human race consists of fools. Shall we say, then, that the wise

man is a mythical ideal held up for our admiration and imitation (LS 66a)?

Hardly, because however much we progress towards this unattainable goal,

we have still come no nearer to salvation. Someone who is only two feet

from the surface is drowning as much as anyone who is 500 fathoms deep

in the ocean (LS 61t).

The Stoics’ doctrine of wisdom and happiness, then, oVers us little

encouragement to strive for virtue. However, later Stoics made a distinc-

tion between doctrine (decreta) and precepts (praecepta), the one being

general and the other particular (Seneca, Ep. 94, 1–4). While the doctrine

is austere and Olympian, the precepts, by an amiable inconsistency, are

often quite liberal and practical. Stoics were willing to give advice on the

conduct of marriage, the right time for singing, the best type of joke, and

many other details of daily life (Epictetus, discourses 4. 12. 16). The

distinction between doctrine and precepts is matched by a distinction

between choice and selection: virtue alone was good and choiceworthy

(D.L. 7. 89), but among indiVerent matters some could be selected in

preference to others. Smart clothes, for instance, were in themselves

worthless; but there could be good in the selection of smart clothes

(Seneca, Ep. 92, 12). Critics said that a selection could be good only if

what was selected was good (LS 64c). Sometimes, again, Stoics spoke as if

the end of life was not so much the actual attainment of virtue as doing

286

ETHICS

one’s best to attain virtue. At this point critics complained that the Stoics

could not make up their minds whether the end of life was the unattain-

able target itself, or simply ineVective assiduousness in target practice (LS

64f, c).

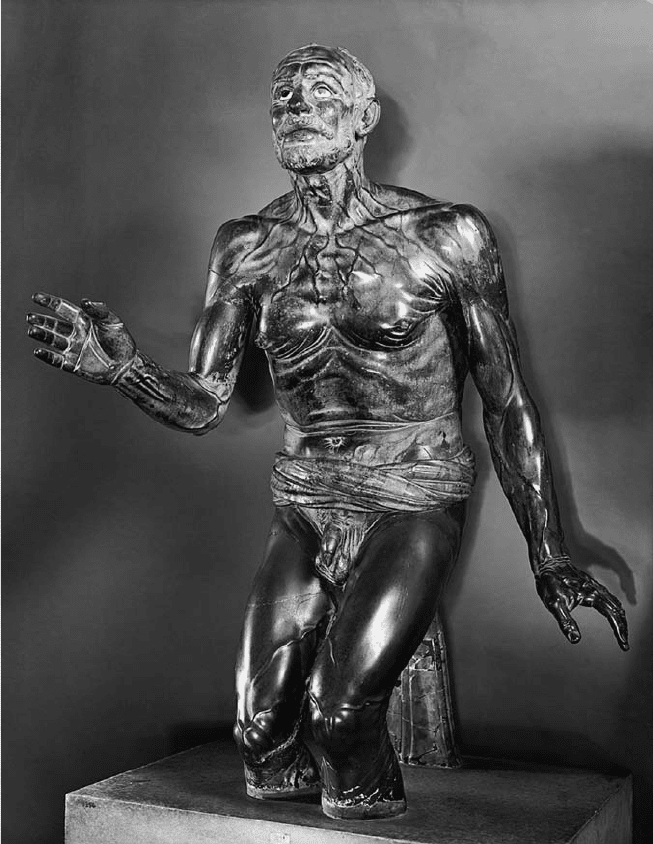

A Roman statue in the Louvre, traditionally entitled ‘The Death of Seneca’

287

ETHICS