Kenny Anthony. Ancient Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy Volume 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

On Divination and Astrology

One doctrine of the Stoics that Cicero vigorously contested was their belief

in divination. His dialogue On Divination takes the form of a conversation

between his brother and himself, with Quintus Cicero defending divination

and claiming that religion stands or falls with the belief in it, while Marcus

Cicero denies the equivalence and denounces divination as puerile super-

stition. Quintus draws some of his material from Chrysippus, who wrote

two books on divination, and collected lists of veridical oracles and dreams

(D 1. 6), while Marcus is indebted for many of his arguments to the

Academic sceptic Carneades.

Divination—the attempt to predict future events which on the face of

them are fortuitous—was practised in Rome in many ways: by the study of

the stars, the observation of the Xight of birds, by the inspection of the

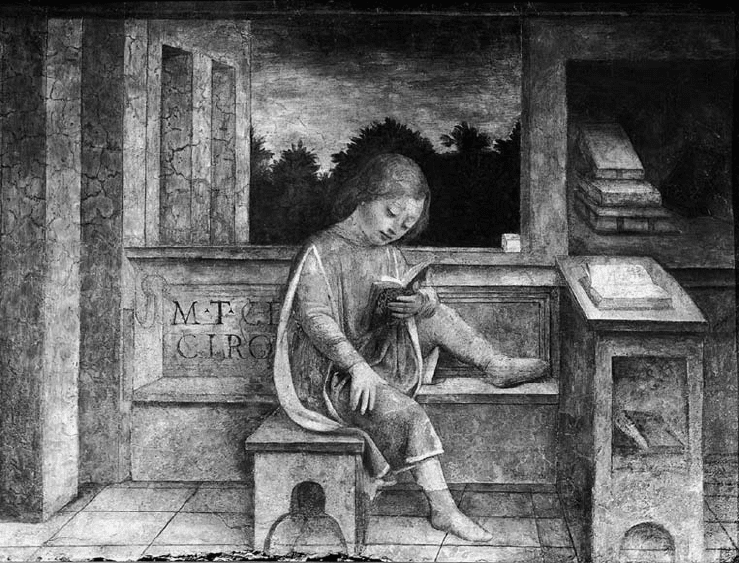

Marcus Tullius Cicero as a diligent schoolboy, in a fresco by V. Foppa

308

GOD

entrails of sacriWced animals, by the interpretation of dreams, and by the

consultation of oracles. Not all of these modes of divination are fashionable

in the modern world, but Cicero’s consideration of astrology is still, sadly,

relevant.

Quintus heaps up anecdotes of remarkable predictions by augurs, sooth-

sayers, and the like, and argues that in principle they are acting no

diVerently from the rest of us when we predict the weather from the

behaviour of birds and frogs or the copiousness of berries on bushes. In

both cases we do not know the reason that links sign and signiWed, but we

do know that there is one, just as when someone throws double sixes a

hundred times in succession we know it is not pure chance. Not all

soothsayers’ predictions come true: but then doctors too make mistakes

from time to time. We may not understand how they make their predic-

tions, but then we don’t understand the operation of the magnet either

(D 1. 86).

Quintus conWrms his empirical evidence with an a priori argument

drawn from the Stoics. If the gods know the future, and do not tell it to

us, then they do not love us, or they think such knowledge will be useless,

or they are powerless to communicate with us. But each of these alterna-

tives is absurd. They must know the future, since the future is what they

themselves decree. So they must communicate the future to us, and they

must give us the power to understand the communication: and that power

is the art of divination (D 1. 82–3). Belief in divination is not superstitious

but scientiWc, because it goes hand in hand with the acceptance of a single

united series of interconnected causes. It is that series that the Stoics call

Fate (D 1. 125–6).

Marcus Cicero beg ins his reply in a down-to-earth manner. If you want

to know what colour a thing is, you had better ask somebody sighted

rather than a blind seer like Tiresias. If you a sick, call a doctor, not a

soothsayer. If you want cosmology, you should go to a physicist, and if you

want moral advice, seek a philosopher, not a diviner. If you want a weather

forecast trust a pilot rather than a prophet.

If an event is a genuine matter of chance, then it cannot be foretold,

for in chance cases there is no equivalent of the causal series that

enables astronomers to predict eclipses (D 2. 15). On the other hand, if

future events are fated, then foreknowledge of a future disaster will not

enable one to avoid it, and the gods are kinder to keep such knowledge

309

GOD

from us. Julius Caesar would not have enjoyed a preview of his own

body stabbed and untended at the foot of Pompey’s statue. The predictions

that divines oVer us contradict each other: as Cato said, it is a wonder

that when one soothsayer meets a nother they can keep a straight face

(D 2. 52).

To match Quintus’ list of prophecies, Marcus compiles a dossier of cases

where the advice of divines was falsiWed or disastrous: both Pompey and

Caesar, for instance, had happy deaths foretold to them. Cicero treats

portents rather as Humeans were later to treat miracles. ‘It can be argued

against all portents that whatever was impossible to happen never in fact

happened; and if what happened was something possible, it is no cause for

wonder’ (D 2. 49). Mere rarity does not make a portent: a wise man is

harder to Wnd than a mule in foal.

The best astronomers, Cicero says, avoid astrological prediction. The

belief that men’s careers are predictable from the position of stars at their

birth is worse than folly: it is unbelievable madness. Twins often diVer in

career and fortune. The observations on which predictions are based are

quite erratic: astrologers have no real idea of the distances between heav-

enly bodies. The rising and setting of stars is something that is relative to an

observer: so how can it aVect alike all those born at the same time?

A person’s ancestry is a better predictor of character than anything in

the stars. If astrology was sound, why did not all the people born at the

same moment as Homer write an Iliad? Did all the Romans who fell in

battle at Cannae have the same horoscope (D 2. 94, 97)?

Finally, Cicero ridic ules the idea that dreams may foretell the future. We

sleep every night and almost every night we dream: is it any wonder that

dreams sometimes come true? It would be foolish of the gods to send

messages by dreams, even if they had time to Xit about our beds. Most

dreams turn out false, and so sensible people pay no attention to them.

Since we possess no key to interpret dreams, for the gods to speak to us

through them would be like an ambassador addressing the Senate in an

African dialect.

With surprisingly little embarrassment, Cicero admits that he himself

has acted as an augur—but only, he says, ‘out of respect for the opinion of

the masses and in the course of service to the state’. He would have

sympathized with the atheist bishops of Enlightenment France. But he

concludes by insisting that he is not himself an atheist: it is not only respect

310

GOD

for tradition, but the order of the heavens and the beauty of the universe

that makes him confess that there is a sublime eternal being that humans

must look up to and admire. But true religion is best served by rooting out

superstition (D 2. 149).

The Trinity of Plotinus

Philosophical theology in the ancient world culminates in the system of

Plotinus. It is thus summed up by Bertrand Russell: ‘The metaphysics

of Plotinus begins with a Holy Trinity: The One, Spirit and Soul. These

three are not equal, like the Persons of the Christian Trinity; the One is

supreme, Spirit comes next, and Soul last.’8 The comparison with the

Christian Trinity is inescapable; and indeed Plotinus, who died before the

church councils of Nicaea and Constantinople gave a deWnitive statement

of the relationships between the three divine persons, undoubtedly had an

inXuence on the thought of some of the Church fathers. But for the

understanding of his own thought it is more rewarding to look backwards.

With some qualiWcation it can be said that the One is a Platonic God,

Intellect (a more appropriate translation for nous than ‘spirit’) is an Aristo-

telian God, and Soul is a Stoic God.

The One is a descendant of the One of the Parmenides and the Idea of

Good in the Republic. The paradoxes of the Parmenides are taken as adumbra-

tions of an ultimately ineVable reality, which is, like the Idea of the Good,

‘beyond being in power and dignity’. ‘The One’, it should be stressed, is not,

for Plato and Plotinus, a name for the Wrst of the natural number series:

rather, it means that which is utterly simple and undivided, all of a piece,

and utterly unique (Ennead 6, 9. 1 and 6). In saying that the One and the

Good (Plotinus uses both names, e.g. 6. 9. 3) is beyond being he does not

mean that it does not exist: on the contrary it is the most real thing there

is. He means that no predicates can be applied to it: we cannot say that it is

this, or it is that. The reason for this is that if any predicate was true of it,

then there would have to be a distinction within it corresponding to the

distinction between the subject and the predicate of the true sentence. But

that would derogate from the One’s sublime simplicity (5. 3. 13).

8 A History of Western Philosophy (London: Allen & Unwin, 1961), 292.

311

GOD

Being has a kind of shape of being, but the One has no shape, not even intelligible

shape. For since its nature is generative of all things, the One is none of them. It is

not of any kind, has no size or quality, is not intellect or soul. It is neither moving

nor stationary, and it is in neither place nor time; in Plato’s words it is ‘by itself

alone and uniform’—or rather formless and prior to form as it is prior to motion

and rest. For all these are properties of being, making it manifold. (6. 9. 3. 38–45)

If no predicates can be asserted of the One, it is not surprising if we enmesh

ourselves in contradiction when we try to do so. Being, for a Platonist, is

the realm of what we can truly know—as against Becoming, which is the

object of mere belief. But if the One is beyond being, it is also beyond

knowledge. ‘Our awareness of it is not through science or understanding,

as with other intelligible objects, but by way of a presence superior to

knowledge.’ Such awareness is a mystical vision like the rapture of a lover

in the presence of his beloved (6. 9. 4. 3 V.).

Because the One is unknowable, it is also ineVable. How then can we

talk about it, and what is Plotinus doing writing about it? Plotinus puts

the question to himself in Ennead 5, 3. 14, and gives a rather puzzling

answer.

We have no knowledge or concept of it, and we do not say it, but we say

something about it. How then do we speak about it, if we do not grasp it. Does

our having no knowledge of it mean that we do not grasp it at all? We do grasp it,

but not in such a way as to say it, only to speak about it.

The distinction between saying and speaking about is puzzling. Could what

Plotinus says here about the One be said about some perfectly ordinary

thing like a cabbage? I cannot say or utter a cabbage; I can only talk about it.

What is meant here by ‘say’ , I think, is something like ‘call by a name’ or

‘attribute predicates to’. This I can do with a cabbage, but not with the One.

And the Greek word whose standard translation is ‘about’ can also mean

‘around’. Plotinus elsewhere says that we cannot even call the One ‘it’ or

say that it ‘is’; we have to circle around it from outside (6. 3. 9. 55).

Any statement about the One is really a statement about its creatures.

We are well aware of our own frailty: our lack of self-suYciency and our

shortfall from perfection (6. 9. 6. 15–35). In knowing this we can grasp the

One in the way that one can tell the shape of a missing piece in a jigsaw

puzzle by know ing the shape of the surrounding pieces. Or, to use a

metaphor closer to Plotinus’ own, when we in thought circle around the

312

GOD

One we grasp it as an invisib le centre of gravity. Most picturesquely,

Plotinus says:

It is like a choral dance. The choir circles round the conductor, sometimes facing

him and sometimes looking the other way; it is when they are facing him that they

sing most beautifully. So too, we are always around him—if we were not we

would completely vanish and no longer exist—but we are not always facing him.

When we do look to him in our divine dance around him, then we reach our goal

and take our rest and sing in perfect tune. (6. 9. 38–45)

We turn from the One to the second element of the Plotinian trinity,

Intellect (nous). Like Aristotle’s God, Intellect is pure activity, and cannot

think of anything outside itself, since this would involve potentiality. But

its activity is not a mere thinking of thinking—whether or not that was

Aristotle’s doctrine—it is a thinking of all the Platonic Ideas (5. 9. 6). These

are not external entities: as Aristotle himself had laid down as a universal

rule, the actuality of intellect and the actuality of intellect’s object is one

and the same. So the life of the Ideas is none other than the activity of

Intellect. Intellect is the intelligible universe, containing forms not only of

universals but also of individuals (5. 9. 9; 5. 7).

Despite the identity of the thinker and the thought, the multiplicity of

the Ideas means that Intellect does not possess the total simplicity which

belongs to the One. Indeed, it is this complexity of Intellect that convinced

Plotinus that there must be something else prior to it and superior to it.

For, he believed, every form of complexity must ultimately depend on

something totally simple.9

The intellectual cosmos is, indeed, boundlessly rich.

In that world there is no stinting nor poverty, but everything is full of life, boiling

over with life. Everything Xows from a single fount, not some special kind of

breath or warmth, but rather a single quality containing unspoilt all qualities,

sweetness of taste and smell, wine on the palate and the essence of every aroma,

visions of colours and every tangible feeling, and every melody and every rhythm

that hearing can absorb. (6. 7. 12. 22–30)

This is the world of Being, Thought, and Life; and though it is the world of

Intellect, it also contains desire as an essential element. Thinking is indeed

itself desire, as looking is a desire of seeing (5. 6. 5. 8–10). Knowledge too is

9 Dominic O’Meara, to whose Plotinus: An Introduction to the Enneads (Oxford: Clarendon Press,

1993) I am much indebted, calls this the Principle of Prior Simplicity (p. 45).

313

GOD

desire, but satisWed desire, the consummation of a quest (5. 3. 10. 49–50). In

the Intellect desire is ‘always desiring and always attaining its desire’ (3. 8.

11. 23–4).

How does Intellect originate? Undoubtedly Intellect derives its being

from the One: the One neither is too jealous to procreate, nor loses

anything by what it gives away. But beyond that Plotinus’ text suggests

two rather diVerent accounts. In some places he says that Intellect eman-

ates from the One in the way that sweet odours are given oV by perfume,

or that light emanates from the sun. This will remind Christian readers of

the Nicene Creed’s proclamation that the Son of God is light from light

(4. 8. 6. 10). But elsewhere Plotinus speaks of Intellect as ‘daring to

apostatize from the One’ (6. 9. 5. 30). This makes Intellect seem less like

the Word of the Christian Trinity, and more like Milton’s Lucifer.

From Intellect proceeds the third element, Soul. Here too Plotinus talks

of a revolt or falling away, an arrogant desire for independence, which took

the form of a craving for metabolism (5. 1. 1. 3–5). Soul’s original sin is well

described thus by A. H. Armstrong:

It is a desire for a life diVerent from that of Intellect. The life of Intellect is a life at

rest in eternity, a life of thought in eternal, immediate, and simultaneous posses-

sion of all possible objects. So the only way of being diVerent which is left for Soul

is to pass from eternal life to a life in which, instead of all things being present at

once, one thing comes after another, and there is a succession, a continuous series,

of thoughts and actions.10

This continuous, restless, succession is time: time is the life of the soul in its

transitory passage from one episode of living to the next (3. 7. 11. 43–5).

Soul is the immanent, controlling element in the universe of nature,

just as God was in the Stoic system, but unlike the Stoic God Soul is

incorporeal. Intellect was the maker of the universe, like the Demiurge of

the Timaeus, but Soul is intellect’s agent in managing its development. Soul

links the intelligible world with the world of the senses, having an inner

element that looks upwards to Intellect and an external element that looks

downwards to Nature (3. 8. 3). Nature is the immanent principle of

development in the material world: Soul, looking at it, sees there its own

10 A. H. Armstrong (ed.), The Cambridge History of Later Greek and Early Medieval Philosophy

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970), 251.

314

GOD

reXection. The physical world that Nature weaves is a thing of wonder and

beauty even though its substance is such as dreams are made of (3. 8. 4).

Plotinus’ theological system is undoubtedly impressive: but we may

wonder whatever kind of argument he can oVer to persuade us to accept

it. To understand this, we have to explore the system from the bottom up,

instead of looking from the top down: we must start not with the One, but

with matter, the outermost limit of reality. Plotinus takes his start from

widely accepted Platonic and Aristotelian principles. He understands Aris-

totle as having argued that the ultimate substratum of change must be

something which possesses none of the properties of the changeable bodies

we see and handle. But a matter which possesses no material properties,

Plotinus argued, is inconceivable.

If we dispense with Aristotelian matter, we are left with Aristotelian

forms. The most important such forms were souls, and it is natural to

think that there are as many souls as there are individual people. But here

Plotinus appeals to another Aristotelian thesis: the principle that forms are

individuated by matter. If we have given up matter, we have to conclude

that there is only a single soul.

To prove that this soul is prior to and independen t of body, Plotinus uses

very much the same arguments as Plato used in the Phaedo. He neatly

reverses the argument of those who claim that soul is dependent on body

because it is nothing more than an attunement of the body’s sinews. When

a musician plucks the strings of a lyre, he says, it is the strings, not the

melody, that he acts on: but the strings would not be plucked unless

the melody called for it.

How can an incorruptible World-Soul be in any way present to individ-

ual corruptible bodies? Plotinus, who liked marine metap hors, explained

this in two diVerent ways. The World-Soul he once compared to a man

standing up in the sea, with half his body in the water and half in the air.

But he thought that we should really ask not how soul is in body, but how

body is in soul. Body Xoats in soul, as a net Xoats in the sea (4. 3. 9. 36–42).

Without metaphor, we can say that body is in soul by depending upon it

for its organization and continued existence.

Soul governs the world wisely and well, but the wisdom that it exercises

in the governance of the world is not native to it, but must come from

outside. It cannot come from the material world, since that is what it

shapes; it must come from something that is by nature linked to the Ideas

315

GOD

that are the models or patterns for intelligent activity. This can only be a

world-mind or Intellect.

We have already encountered the arguments whereby Plotinus shows

that Intellect cannot be the ultimate reality because of the duality of

subject and object and because of the multiplicity of the Ideas. Thus, at

the end of our journey, we reach the one and only One.

Plotinus’ theology continued to be taught, with modiWcations, until

Western pagan philosophy came to an end with the closure of the school of

Athens. But his inXuence lived on, and lives on, unacknowledged, through

the ideas that were absorbed and transmitted by his Wrst Christian readers.

Most important of these was Aug ustine, who read him as a young man in

the transl ation of Marius Victorinus. The reading set him on the course

which led to his conversion to Christianity, and his Confessions and On the

Trinity contain echoes of Plotinus on many a page. In the last days of his life,

we are told, when the Vandals were besieging Hippo, he consoled himself

with a quotation from the Enneads: ‘How can a man be taken seriously if

he attaches importance to the collapse of wood and stones, or to the

death—God help us—of mortal creatures?’ (1. 4. 7. 24–5).

GOD

316

CHRONOLOGY

585 BC Thales predicts an eclipse

547 Anaximander dies

530 Pythagoras migrates to Italy

525 Anaximenes dies

500 Heraclitus in mid-life

470 Xenophanes dies

Democritus born

469 Socrates born

450 Parmenides and Zeno visit Athens

Empedocles in mid-life

444 Protagoras writes a constitution

427 Plato born

399 Socrates executed

387 Plato’s Academy founded

384 Aristotle born

347 Plato dies

336 Alexander king of Macedon

322 Aristotle dies

313 Zeno of Citium comes to Athens

306 Epicurus founds the Garden

273 Arcesilaus becomes head of the Academy

263 Cleanthes becomes head of the Stoa

232 Chrysippus succeeds as head of the Stoa

155 Carneades heads the Academy and visits Rome

106 Cicero born

55 Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura

44 Julius Caesar assassinated

30 Augustus becomes Emperor

52AD St Paul preache s in Athens

65 Suicide of Seneca