Kenny Anthony. Ancient Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy Volume 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Contrasted with universal propositions there are particular propositions

(en merei) such as ‘Some Greeks are bearded’ (a particular afWrmative) or

‘Some Greeks are not bearded’ (a particular negative). In propositions of all

these kinds, Aristotle says, something is predicated of something else: e.g.

mortal is predicated of human in one case, and horse of Greek in another.

The presence or absence of a negative sign determine whether these

predications are afWrmations or negations respectively (1. 1. 24b17).

The items that enter into predications in propositions are called by

Aristotle terms (horoi). It is a feature of terms, as conceived by Aristotle,

that they can e ither Wgure as predicates themselve s or have other terms

predicated of them. Thus, in our Wrst example, human is predicated of

something in the Wrst sentence and has something predicated of it in the

second.

Aristotle assigns the terms occurring in a syllogism three distinct roles.

The term that is the predicate of the conclusion is the major term; the term

of which the major is predicated in the conclusion is the minor term; and the

term that appears in each of the premisses is the middle term (1. 4. 26a21–3).1

Thus, in the example given ‘mortal’ is the major term, ‘Greek’ the minor

term, and ‘human’ the middle term.

In addition to inventing these technical terms, Aristotle introduced the

practice of using schematic letters to bring out patterns of argument: a

device that is essential for the systematic study of inference and which is

ubiquitous in modern mathematical logic. Thus, the pattern of argument

we illustrated above is set out by Aristotle not by giving an example, but by

the following schematic sentence:

If A belongs to every B, and B belongs to every C, A belongs to

every C.2

If Aristotle wishes to produce an actual example, he commonly does it not

by spelling out a syllogistic argument, but by giving a schematic sentence

and then listing possible substitutions for A, B, and C (e.g. 1. 5. 27b30–2).

1 Aristotle’s use of these terms in the Prior Analytics is not consistent: the account given here,

from which he departs in considering the second and third Wgures of syllogism, has been

accepted as canonical since antiquity (see W. C. Kneale and M. Kneale, The Development of Logic

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962), 69–71).

2 Note that beside being cast in schematic form, Aristotle’s exposition of syllogisms follows

the pattern ‘If p and q, then necessarily r’ rather than ‘p, q therefore r’.

118

LOGIC

All syllogisms will contain three terms and three propositions; but given

that there are the four diVerent kinds of proposition Aristotle has distin-

guished, and that there are diVerent orders in which the terms can appear

in the premisses, there will be many diVerent syllogistic inference patterns.

Unlike our initial example, which contained only afWrmative universal

propositions, there will be triads containing negative and particular

propositions. Again, unlike our example in which the middle term

appeared in the Wrst premiss as a predicate and in the second as a subject,

there will be cases where the middle is subject in each premiss and cases

where it is predicate in each premiss. (By Aristotle’s preferred deWnition,

the conclusion will always have the minor term as its subject and the

major as its predicate.)

Aristotle grouped the triads into three Wgures (schemata) on the basis of

the position occupied in the premisses by the middle term. The Wrst Wgure,

illustrated by our initial example, has the middle once as predicate and

once as subject (the order in which the premisses are stated is immaterial).

In the second Wgure the middle term appears twice as subject, and in the

third Wgure it appears twice as predicate. Thus, using S for the minor, M for

the middle, and P for the major term, we have these Wgures:

(1) (2) (3)

S–M M–S S–M

M–P M–P P–M

Therefore, S–P S–P S–P

Aristotle was mainly interested in syllogisms of the Wrst Wgure, which he

regarded as alone being ‘perfect’, by which he probably meant that they had

an intuitive validity that was lacking to syllogisms in other Wgures (1. 4. 25b35).

Predication occurs in all propositions, but it comes in diVerent forms in the

four diVerent kinds of proposition: universal afWrmative, universal negative,

particular afWrmative, particular negative. Thus the predication S–P can be

either ‘All S is P’, ‘No S is P’, ‘Some S is P’, or ‘Some S is not P’. Within each

Wgure, therefore, we have many possible patterns of inference. In the Wrst

Wgure, for instance, we have, among many possibilities, the two following.

Every Greek is human. Some a nimals are dogs.

No human is immortal. Some dogs are white.

No Greek is immortal. Every animal is white.

119

LOGIC

Triads of these diVerent kinds were, in later ages, called ‘moods’ of the

syllogism. Both of the given triads exemplify the pattern of a syllogism of

the Wrst Wgure, but there is obviously a great diVerence between them: the

Wrst is a valid argument, the second is invalid, having true premisses and a

false conclusion.3

Aristotle sets himself the task of determining which of the possible

moods produces a valid inference. He addresses it by trying out the various

possible pairs of premisses and asking whether any conclusion can be

drawn from them. If no conclusion can be validly drawn from a pair of

premisses, he says that there is no syllogism. For instance, he says that if B

belongs to no C, and A belongs to some B, there cannot be a syllogism; and

he gives the terms ‘white’, ‘horse’, ‘swan’ as the test instance (1. 3. 25a38).

What he is doing is inviting us to consider the pair of premisses ‘No swan is

a horse’ and ‘Some horses are white’ and to observe that from these

premisses no conclusion can be drawn about the whiteness or otherwise

of swans.

His procedure appears, at Wrst sight, to be both haphazard and intuitive;

but in the course of his discussion he is able to produce a number of general

rules which, between them, are adequate to determine which moods yield

a conclusion and which do not. There are three rules which apply to

syllogisms in all Wgures:

(1) At least one premiss must be universal.

(2) At least one premiss must be afWrmative.

(3) If either premiss is negative, the conclusion must be negative.

These rules are of universal application, but they take more speciWc

form in relation to particular Wgures. The rules peculiar to the Wrst

Wgure are

(4) The major premiss (the one containing the major term) must be

universal.

(5) The minor premiss (the one containing the minor term) must be

afWrmative.

3 No valid argument has true premisses and a false conclusion, but of course there can be

valid arguments from false premisses to false conclusions, and invalid arguments for true

conclusions.

120

LOGIC

If we apply these rules we Wnd that there are four, and only four, valid

moods of syllogism in the Wrst Wgure.

Every S is M Every S is M Some S is M Some S is M

Every M is P No M is P Every M is P Every M is not P

Every S is P No S is P Some S is P Some S is not P

Aristotle also oVers rules to determine the validity of moods in the second

and third Wgures, but we do not need to go into these since he is able

to show that all second- and third- Wgure syllogisms are equivalent to

Wrst-Wgure syllogisms. In general, syllogisms in these Wgures can be

transformed into Wrst-Wgure syllogisms by a process he calls ‘conversion’

(antistrophe).

Conversion depends on a set of relations between propositions of

diVerent forms that Aristotle sets out early in the treatise. When we have

particular afWrmative and universal negative propositions, the order of the

terms can be reversed without alteration of sense: Some S is P if and only if

some P is S, and no S is P if and only if no P is S (1. 2. 25a5–10). (By contrast,

‘Every S is P’ may be true without ‘Every P is S’ being true.)

Consider the following syllogism in the third Wgure: ‘No Greek is a bird;

but all ravens are birds; therefore no Greek is a raven’. If we convert the

minor premiss into its equivalent ‘No bird is a Greek’ we have a Wrst-Wgure

syllogism in the second of the moods tabulated above. Aristotle shows in

the course of his treatise that almost all second- and third-Wgure syllogisms

can be reduced to Wrst-W gure ones by conversion in this manner. In the

rare cases where this is not possible he transforms the second- and third-

Wgure syllogisms by a process of reductio ad absurdum, showing that if one

premiss of the syllogism is taken in conjunction with the negation of its

conclusion as a second premiss, it will yield (by a deduction in the Wrst

Wgure) the negation of the original second premiss as a conclusion (1. 23.

41a21 V.).

Aristotle’s syllogistic was a remarkable achievement: it is a systematic

formulation of an impo rtant part of logic. Some of his followers in later

times—though not in antiquity or the Middle Ages—thought that syllo-

gistic was the whole of logic. Immanuel Kant, for instance, in the preface to

the second edition of his Critique of Pure Reason, said that since Aristotle logic

had neither advanced a single step nor been requi red to retrace a single

step.

121

LOGIC

In fact, however, syllogistic is only a fragment of log ic. It deals only with

inferences that depend on words like ‘all’ or ‘some’, which classify the

premisses and conclusions of syllogisms, not with inferences that depend

on words like ‘if’ and ‘then’, which, instead of attaching to nouns, link

whole sentences. As we shall see, inferences such as ‘If it is not day, it is

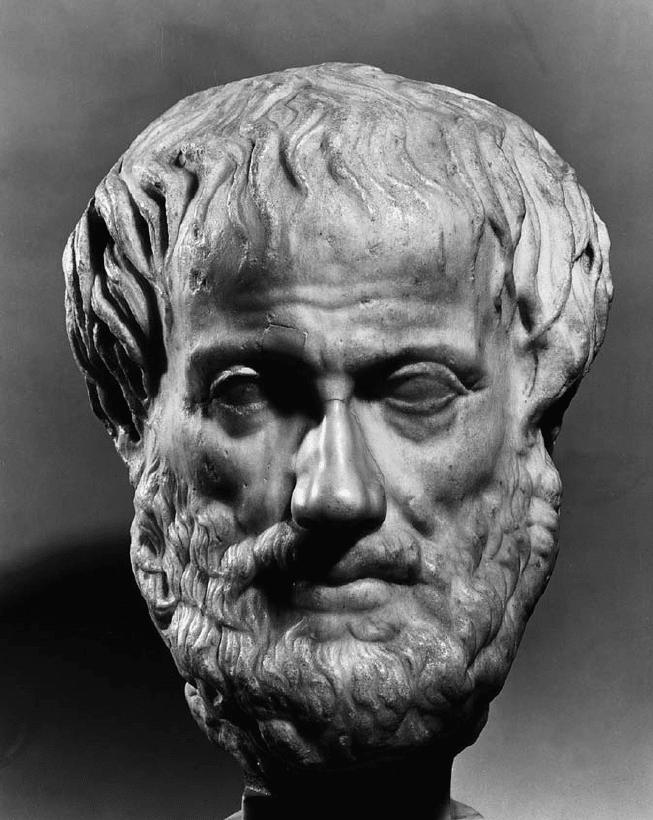

A head of Aristo tle attributed to Lys ippus (fourth century bc)

122

LOGIC

night; but it is not day; therefore it is night’ were formalized later in

antiquity. Another gap in Aristotle’s syllogistic took longer to Wll. Though

it was concerned above all with words like ‘all’, ‘every’, and ‘some’

(quantiWers, as they were later to be called), it could not cope with

inferences in which such words occurred not in subject place but some-

where in the grammatical predicate. Aristotle’s rules would not provide for

assessing the validity of inferences containing premisses such as ‘Every boy

loves some girl’ or ‘Nobody can avoid every mistake.’ It took more than

twenty centuries before such inferences were satisfactorily formalized.

Aristotle may perhaps, for a moment, have thought that his syllogistic

was sufWcient to deal with every possible valid inference. But his own

logical writings show that he realized that there was much more to logic

than was dreamt of in his syllogistic.

The de Interpretatione and the Categories

The de Interpretatione is principally interested, like the Prior Analytics, in general

propositions beginning with ‘every’, ‘no’, or ‘some’. But its main concern is

not to link them to each other in syllogisms, but to explore the relations of

compatibility and incompatib ility between them. ‘Every man is white’ and

‘No man is white’ can clearl y not both be true together: Aristotle calls such

propositions contraries (enantiai) (7. 17b4–15). They can, however, both be false,

if, as is the case, some men are white and some men are not. ‘Every man is

white’ and ‘Some man is not white’, like the earlier pair, cannot be true

together; but—on the assumption that there are such things as men—

they cannot be false together. If one of them is true, the other is false; if one

of them is false, the other is true. Aristotle calls such a pair contradictory

(antikeimenai) (7. 17b16–18).

Just as a universal afWrmative is contradictory to the corresponding

particular negative, so too a universal negative contradicts, and is contra-

dicted by, a particular afWrmative: thus ‘No man is white’ and ‘Some man is

white’. Two corresponding particular afWrmatives are neither contrary nor

contradictory to each other: ‘Some man is white’ and ‘Some man is not white’

can be, and in fact are, both true together. Given that there are men, the

propositions cannot, however, both be false together. This relationship was

not given a name: later followers called it the relationship of subcontrariety.

123

LOGIC

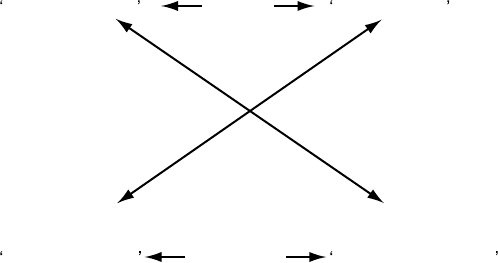

Contra

dictory

Contra dictory

Contrary

Universal affirmative Universal negative

Every man is white No man is white

Particular affirmative Particular negative

Some man is white Some man is not whiteSubcontrary

The relationships set out in the de Interpretatione can be set out, and have

been set out for centuries by Aristotle’s followers, in a diagram known as a

square of opposition.

The propositions that enter into syllogisms and into the square of

opposition are all general propositions, whether they are universal or

particular. That is to say, none of them are propositions about individuals,

containing proper names, such as ‘Socrates is wise’. Of course, Aristotle was

familiar with singular propositions, and one such, ‘Pittacus is generous’,

turns up in an example in the Wnal chapter of the Prior Analytics (2. 27. 70a25).

But its appearance is incongruous in a treatise whose standard assumption

is that all premisses and conclusions are quantiWed general propositions. In

the de Interpretatione singular propositions are mentioned from time to time,

principally to point a contrast with general propositions. It is a simple

matter, for instance, to form the contradictory of ‘Socrates is white’: it is

‘Socrates is not white’ (7. 17b30). But to Wnd a systematic treatment of

singular propositions we must turn to the Categories.

Whereas the Analytics operates with a distinction between propositions

and terms, the Categories starts by dividing ‘things that are said’ into

complex (kata symploken) and simple (aneu symplokes) (2. 1a16). An example of

a complex saying is ‘A man is running’; simple sayings are the nouns and

verbs that enter into such complexes: ‘man’, ‘ox’, ‘run’, ‘win’, and so on.

Only complex sayings can be statements, true or false; simple sayings are

neither true nor false. A similar distinction appears in the de Interpretatione,

where we learn that a sentence (logos) has parts that signify on their own,

124

LOGIC

while on the other hand there are signs that have no signiWcant parts.

These simple signs come in two diVerent kinds, names (Int.2.16a20–b5) and

verbs (Int.3.16b6–25): the two are distinguished from each other, we learn,

because a ver b, unlike a noun, ‘signiWes time in addition’, i.e. has a tense.

But in the Categories there is a much richer classiWcation of simple sayings. In

the fourth chapter of the treatise Aristotle has this to say:

Each one signiWes either substance (ousia), or how big, or what sort, or in relation to

something, or where, or when, or posture, or wearing, or doing, or being acted on.

To give a rough idea substance is e.g. human, horse; how big is e.g. four-feet, six-

feet; what sort is e.g. white, literate; in relation to something is e.g. double, half,

bigger than; where is e.g. in the Lyceum, in the forum; when is e.g. yesterday,

tomorrow, last year; posture is e.g. is lying, is sitting; wearing is e.g. is shod, is

armed; doing is e.g. cutting, burning; being acted on is e.g. being cut, being burnt.

(4. 1b25–2a4)

This compressed and cryptic passage has received repeated commentary

and has exercised enormous inXuence over the centuries. These ten things

signiWed by simple sayings are the categories that give the treatise its name.

Aristotle in this passage indicates the categories by a heterogene ous set of

expressions: nouns (e.g. ‘substance’), verbs (e.g. ‘wearing’), and interroga-

tives (e.g. ‘where?’ or ‘how big?’). It became customary to refer to every

category by a more or less abstract noun: substance, quantity, quality,

relation, place, time, posture, vesture, activity, passivity.

What are c ategories and what is Aristotle’s purpose in listing them? One

thing, at least, that he is doing is listing ten diVerent kinds of expression

that m ight appear in the predicate of a sentence about an individual

subject. We might say of Socrates, for example, that he was a man, that

he was Wve feet tall, that he was wise, that he was older than Plato, and that

he lived in Athens in the Wfth century bc. On a particular occasion his

friends might have said of him that he was sitting, wearing a cloak, cutting

a piece of cloth, and being warmed by the sun. Obviously, the teaching of

the Categories makes room for a variety of statements much richer than the

regimented propositions of the Prior Analytics.

The text makes clear, however, that Aristotle is not only classifying

expressions, pieces of language. He saw himself as making a classiWcation

of extra-linguistic entities, things signiWed as opposed to the signs that

signify them. In Chapter 6 we shall explore the metaphysical implications

of the doctrine of the categories. But one question must be addressed

125

LOGIC

immediately. If we follow Aristotle’s lead, we shall easily be able to categor-

ize the predicates in sentences such as ‘Socrates was pot-bellied’, ‘Socrates

was wiser than Meletus’. But what are we to say about the ‘Socrates’ in such

sentences? Aristotle’s list seems to be a list of predicates not of subjects.

The answer to this is given in the succeeding chapter of the Categories.

Substance—strictly so called, primarily and par excellence—is that which is neither

said of a subject nor is in a subject, e.g. such-and-such a man, such-and-such a

horse.

Second substances are the species and genera to which the primary substances

belong. Thus, such-and-such a man belongs in the species human, and the genus

of this species is animal; so both human and animal are called second substances.

(5. 2a11–19)

When Aristotle speaks of a subject in this passage, it is clear that he is

talking not about a linguistic expression, but about what the expression

stands for. It is the man Socrates, not the word ‘Socrates’, that is the Wrst

substance. The substance that appeared Wrst in the list of categories, it now

emerges, was second sub stance: so the sentence ‘Socrates was human’

predicated a second substance (a species) of a Wrst substance (an individual).

When Aristotle in this passage c ontrasts a Wrst substance with things that

are in a subject, what he has in mind as being in a subject are the items

signiWed by predicates in the other categories. Thus, if ‘Socrates is wise’ is

true, then Socrates’ wisdom is one of the things that are in Socrates (cf. 2.

1a25).

Aristotle goes through the categories, discussing them in turn. Some,

such as substance, quantity, and quality, are treated at length; others, such

as activity and passivity, are brieXy touched on; yet others, such as posture

and vesture, pass into oblivion. Detailed logical points are made in order to

mark the distinctions between diVerent categories. For example, qualities

often admit of degrees, while particular quantities do not: one thing can be

darker than another, but cannot be more four-foot-long than another

(7. 6a19; 8. 10b26). Within individual categories, further subclasses are

identiWed. There are, for instance, two types of quantity (discrete and

continuous) and four types of quality, which Aristotle illustrates with

the following examples: virtue, healthiness, darkne ss, shape. The criteria

by which he distinguishes these types are not altogether clear, and the

reader is left in doubt whether a particular item can occur in more than

one of these classes, or indeed in more than one category. Aristotle’s

126

LOGIC

commentators through the ages have laboured to Wll his gaps and reconcile

his inconsistencies.

The Categories contains more than the theory of categories: it deals also

with a mixed bag of other logical topics. It is clear that the treatise we have

was not written as a single whole by Aristotle, though there is no need to

question, as some scholars have done, that it is his authentic work.4

One cluster of topics discussed is that of homony my and synonymy.

These words are transliterations of the Greek words Aristotle uses; but

whereas the English words signify properties of bits of language, the Greek

words as he uses them signify properties of things in the world. Aristotle’s

account can be paraphrased thus: if A and B are called by the same name

with the same meaning, then A is synonymous with B; if A and B are called

by the same name with a diVerent meaning, then A is homonymous with

B. Because of peculiarities of Greek idiom, we have to tweak Aristotle’s

examples in English, but it is clear enough what he has in mind. A Persian

and a tabby are synonymous with each other because they are both called

cats; but they are only homonymous with the nine-tailed whip that is also

called a cat. The diVerence between homonymous and synonymous

things, Aristotle says, is that homonymous things have only the name in

common, whereas synonymous things have both the name and its deWni-

tion in common.

Aristotle’s distinction between homonymous and synonymous things is

an important one which is easily adapted—and was indeed later adapted by

himself—into a distinction between homonymous and synonymous bits of

language, that is to say between expressions that have only the symbol in

common and those that have also the meaning in common.

The study of homonymy was important for the treatment of fallacies in

arguments due to the ambiguity of terms used. It is undertaken for these

purposes in the Topics, and Aristotle gives rules for detecting it. ‘Sharp’, for

instance, has one meaning as applied to knives, and another as applied to

musical notes: the homonymy is made obvious because in the case of

knives the opposite of ‘sharp’ is ‘blunt’, whereas in the case of notes the

opposite is ‘Xat’ (Top. 1. 15. 106a13–14). In the course of his studies Aristotle

came to draw a distinction between mere chance homonymy (as in the

English word ‘bank’, which is used both for the side of a river and for a

4 With the exception of 8. 11 a10–18, an editorial insertion to link together two of the disparate

elements and to explain gaps in the treatment of the later categories.

127

LOGIC