Kenny Anthony. Ancient Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy Volume 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Epictetus’ dates are uncertain, but we know that he was banished from

Rome, along with other philosophers, by the emperor Domitian in ad 89.

Freed from slavery, though permanently lamed, he set up a school in

Epirus; his admirer Arrian published four books of his discourses and a

handbook of his main teachings (enchiridion). Epictetus is one of the most

readable of the Stoics, and has a rugged and jocular style, making constant

use of cross-talk with imaginary interlocutors. Because of this, many

people beside philosophers have found him attractive. Matthew Arnold

lists him, along with Homer and Sophocles, as one of three men who have

most enlightened him:

He, whose friendship I not long since won,

That halting slave, who in Nicopolis

Taught Arrian, when Vespasian’s brutal son

Cleared Rome of what most shamed him.

Typical of Epictetus’ style is the following passage on suicide, where he

imagines people suVering from tyranny and injustice addressing him thus:

Epictetus, we can no longer endure imprisonment in this bodikin, feeding it and

watering it and resting it and washing it, and being brought by it into contact with

so-and-so and such-and-such. Aren’t these things indiVerent, indeed a very

nothing, to us? Death isn’t an evil, is it? Aren’t we God’s kin, and don’t we

come from him? Do let us go back where we came. (1. 9. 12)

He responds as follows:

Men, wait for God. When he gives the signal and releases you from this service,

then you may go to him. For the time being, though, stay at the post where he has

stationed you.

Rather than seek refuge in suicide, we should realize that none of the

world’s evils can really harm us. To show this, Epictetus identi W es the self

with the moral will (prohairesis).

When the tyrant threatens and summons me, I answer, ‘Who is it that you are

threatening?’ If he says, ‘I will put you in chains,’ I respond, ‘It is my hands and my

feet he is threatening.’ If he says, ‘I will behead you,’ I respond, ‘It is my neck he is

threatening.’ ...Sodoesn’t he threaten you at all? No, not so long as I regard all this

as nothing to me. But if I let myself fear any of these threats, then yes, he does

threaten me. Who then is left for me to fear? A man who can master the things in

my own power?—There is no such man. A man who can master the things that

are not in my power?—Why should I trouble myself about him? (Disc. 1. 29)

108

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

In many periods Epictetus’ writings have been found comforting by those

who have had to live under the rule of tyrants. But in his own time the

person who was most impressed by them was himself the ruler of the

Roman world. Marcus Aurelius Antoninus became emperor in 161 and

spent much of his life defending the frontiers of the Roman Empire, now at

its furthest extent. Though himself a Stoic, he founded chairs of philoso-

phy at Athens for all of the major schools, Platonic, Peripatetic, and

Epicurean. During his military campaigns he found time to make entries

into a philosophical notebook, which has been known in modern times as

the Meditations. It is a collection of aphorisms and discourses on themes such

as the brevity of life, the need to work for the common good, the unity of

mankind, and the corrupting nature of power. He sought to combine

patriotism with a universalist viewpoint. ‘My city and country,’ he says, ‘so

far as I am Antoninus, is Rome; but so far as I am a man, it is the world.’ He

hails the universe as ‘Dear City of Zeus’.

One of Marcus Aurelius’ friends was the medical doctor Galen, who

came to Rome after being physician to the gladiators of Pergamum. His

voluminous writings belong rather to the history of medicine than to that

of philosophy, though he was a serious logician and once wrote a treatise

with the title That a Good Doctor Must Be a Philosopher. He corrected Aristotle’s

physiology on an important point which was crucial for a true appreciation

of the mind–body relationship. Aristotle had believed that the heart was

the seat of the soul, regarding the brain as a mere radiator to cool the

blood. Galen discovered that nerves arising from the brain and spinal cord

are necessary for the initiation of muscle contraction, and hence he

regarded the brain, and not the heart, as the primary seat of the soul.

Early Christian Philosophy

With Marcus Aurelius, Stoicism took its last bow, and Epicureanism was

already in retirement. Among the schools of philosophy to whom the

emperor assigned chairs in Athens, one was conspicuous by its absence:

Christianity. Indeed, Marcus instituted a cruel persecution of Christians,

and dismissed their martyrdoms as histrionic. One of those who was

executed in his reign was Justin, the Wrst Christian philosopher, who had

dedicated to him an Apologia for Christianity.

109

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

It was at the end of the second century that Christians Wrst made

substantial attempts to harmonize the religion of Jesus and Paul with the

philosophy of Plato and Aristotle. Clement of Alexandria published a set of

Miscellanies (Stromateis), written in the style of table talk, in which he argued

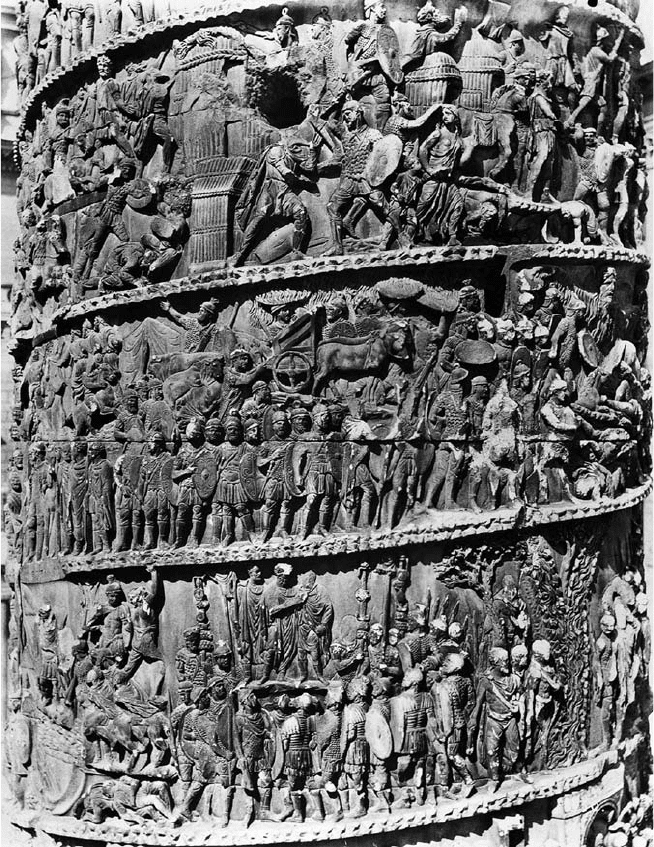

The campaigns of Marcus Aurelius, depicted on his column in Rome

110

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

that the study of philosophy was not only permiss ible, but necessary, for the

educated Christian. The Greek thinkers were pedagogues for the world’s

adolescence, divinely appointed to bring it to Christ in its maturity. Clement

enrolled Plato as an ally against dualist Christian heretics, he experimented

with Aristotelian logic, and he praised the Stoic ideal of freedom from

passion. In the manner of Philo, he explained away as allegorical aspects of

the Bible, and especially the Old Testament, which repelled educated Greeks.

In this he founded a tradition that was to have a long history in Alexandria.

Clement was an anthologist and a popularizer; his younger Alexandrian

contemporary Origen (185–254) was an original thinker. Though he

thought of himself primarily as a student of the Bible, Origen had sat at

the feet of the Alexandrian Platonist Ammonius Saccas, and he incorpor-

ated into his system many philosophical ideas which mainstream Christians

regarded as heretical. He believed, with Plato, that human souls existed

before birth or conception. Formerly free spirits, human souls in their

embodied state could use their free will to ascend, aided by the grace of

Christ, to a heavenly destiny. In the end, he believed, all rational beings,

sinners as well as saints, and devils as well as angels, would be saved and Wnd

blessedness. There would be a resurrection of the body which (according to

some of our sources) he believed would take spherical form, since Plato had

decreed that the sphere was the most perfect of all shapes.

Origen’s eccentric teaching brought him into conXict with the local

bishops, and his loyalty to Christianity laid him under the ban of the

empire. He was exiled to Palestine, where, against his pagan fellow Platonist

Celsus, he used philosophical arguments to defend Christian belief in God,

freedom, and immortality. He died in 254 after repeated torture in the

persecution of the emperor Decius.

The Revival of Platonism and Aristotelianism

While Christian philosophy was in its infancy, and while Stoicism and

Epicureanism were in decline, there had been a fertile revival of the

philosophy of Plato and Aristotle. Plutarch (c.46–c.120) was born in

Boeotia and spent most of his life there, but he had studied at Athens

and at least once gave lectures in Rome. He is best known as a historian

for his parallel lives of twenty-three famous Greeks paired with twenty-

111

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

three famous Romans, which in an Elizabethan translation by Sir Thomas

North provided the plot and much of the inspiration for Shakespeare’s

Roman plays. But he also wrote some sixty short treatises on popular

philosophical topics, which were collected under the title Moralia. He was

a Platonist and commented on the Timaeus. He wrote a number of

polemical treatises against the Stoics and Epicureans which contributed

to the decline of those systems: they bear parallel titles such as On the

Contradictions of the Epicureans and On the Contradictions of the Stoics or On Free Will

in Reply to Epicurus and On Free Will in Reply to the Stoics . One of the longest of

his surviving essays bears the title That Epicurus Actually Makes a Pleasant Life

Impossible, and another is an attack on an otherwise unknown work by

Colotes, one of Epicurus’ earliest disciples. Though his works are not

often read by philosophers for their own sake, they have long been

quarried by historians for the information they provide about their targets

of attack.

More important, initially, than the incipient revival of Platonism was

the beginning of a tradition of scholarly commentary on the Aristotelian

corpus. The oldest surviving commentary on a text is the second-

century work of Aspasius on the Ethics, which inaugurates the custom

of treating the Nicomachean Ethics as canonical. At the end of the century

Alexander of Aphrodisias was appointed to the Peripatetic chair in

Athens, and he produced extensive commentaries on the Metaphysics,

the de Sensu, and some of the logical works. In pamphlets on the soul,

and on fate, he presented his own developments of Aristotelian ideas.

Aristotle had spoken, obscurely, of an active intellect that was respon-

sible for concept formation in human beings. Alexander identiWed this

active intellect with God, an interpretation that was to have a great

inXuence on Aristotle’s later Arab followers, while being rejected by

Christians, who regarded the active intellect as a faculty of each individ-

ual human being.

Plotinus and Augustine

It was Plato, however, not Aristotle, who was to be the dominant philo-

sophical inXuence during the twilight of classical antiquity. Contemporary

with the Christian Origen, and a fellow pupil of Ammonius Saccas, was the

112

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

last great pagan philosopher, Plotinus (205–70). After a brief military career

Plotinus settled in Rome and won favour at the imperial court. He toyed

with the idea of founding a Platonic republic in Campania. His works were

edited after his death in six groups of nine treatises (Enneads) by his disciple

and biographer Porphyry. Written in a taut and diYcult style, they cover a

variety of philosophical topics: ethics and aesthetics, physics and cosmol-

ogy, psychology, metaphysics, logic, and epistemology.

The dominant place in Plotinus’ system is occupied by ‘the One’: the

notion is derived, through Plato, from Parmenides, where Oneness is a key

property of Being. The One is, in a mysterious way, identical with the

Platonic Idea of the Good: it is the basis of all being and the standard of all

value, but it is itself beyond being and beyond goodness. Below this supreme

and ineVable summit, the next places are occupied by Mind (the locus of

Ideas) and Soul, which is the creator of time and space. Soul looks upward to

Mind, but downward to Nature, which in turn creates the physical world.

At the lowest level of all is bare matter, the outermost limit of reality.

These levels of reality are not independent of each other. Each level

depends for its existence and activi ty on the level above it. Everything has

its place in a single downward progress of successive emanations from the

One. This impressive and startling metaphysical system is presented by

Plotinus not as a mystical revelation but on the basis of philosophical

principles derived from Plato and Aristotle. It will be examined in detail

in Chapter 9 belo w.

Plotinus’ school in Rome did not survive his death, but his pupils and

their pupils carried his ideas elsewhere. A Neoplatonic tradition throve in

Athens until the pagan schools were closed down by the Christian emperor

Justinian in 529. But it was Christians, not pagans, who transmitted

Plotinus’ ideas to the post-clas sical world, and foremost among them was

St Augustine of Hippo, who was to prove the most inXuential of all

Christian philosophers.

Augustine was born in a small town in present-day Algeria in 354. The son

of a Christian mother and a pagan father, he was not baptized as an infant,

though he received a Christian education in Latin literature and rhetoric.

Most of what we know of his early life comes from his own autobiography,

the Confessions, a portrait, by a biographer nearly as gifted as Boswell, of a

mind more capacious than Johnson’s.

113

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

Having acquired a smattering of Greek, Augustine qualiWed in rhetoric

and taught the subject at Carthage, a city which he described as ‘a cauldron

of unholy loves’. At the age of 18, reading Cicero’s Hortensius,hewasWred

with a love of Plato. For about ten years he was a follower of Manichaeism,

a syncretic religion which taught that there were two worlds, one of

spiritual goodness and light created by God, and one of Xeshly darkness

created by the devil. The distaste for sex left a permanent mark on

Augustine, though for several years in early manhood he lived with a

mistress and had with her a son, Adeodatus.

In 383 he crossed the sea to Rome and quickly moved to Milan, then the

capital of the western part of the now divided Roman Empire. There

he became friends with Ambrose, the bishop of Milan, a great champion

of the claims of religion and morality against the ruthless secular power of

the emperor Theodosius. The inXuence of Ambrose, and of his mother,

Monica, turned Augustine in the direction of Christianity. After a period of

hesitation he was baptized in 387.

For some time after his baptism Augustine remained under the philo-

sophical inXuence of Plotinus. A set of dialogues on God and the human

soul articulated a Christian Neoplatonism. Against the Academics set out a

detailed line of argument against Academic Scepticism. In On Ideas he

presented his own version of Plato’s Theory of Ideas: the Ideas have no

extra-mental existence, but they exist, eternal and unchangeable, in the

mind of God. He wrote On Free Choice on human freewill, choice, and

the origin of evil, a text still used in a number of philosophy departments.

He also wrote a donnish Platonic tract, the 83 DiVerent Questions. He also

wrote six books on music, and an energetic work On the Teacher,reXecting

imaginatively on the nature and power of words.

All these works were written before Augustine found his Wnal vocation

and was ordained as a priest in 391. He became after a short period bishop of

Hippo in Algeria, where he resided until his death in 430. He had a

prodigious writing career ahead of him, including his masterpiece

The City of God, but the year 391 marks an epoch. Up to this point Augustine

showed himself the last Wne Xower of classical philosophy. From then

onwards he writes not as the pupil of the pagan Plotinus, but as the father

of the Christian philosophy of the Middle Ages. We shall follow him into

this creative phase in the next volume of this work.

114

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

Augustine did not see himself, in his maturity, as a philosophical

innovator. He saw his task as the expounding of a divine message that

had come to him from Plato and Paul, men much greater than himself,

and from Jesus, who was more than man. But the way in which succeeding

generations have conceived and understood the teaching of Augustine’s

masters has been in great part the fruit of Augustine’s own work. Of all the

philosophers in the ancient world, only Aristotle had a greater inXuence

on human thought.

115

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

3

How to Argue:

Logic

L

ogic is the discipline that sorts out good arguments from bad

arguments. Aristotle claimed to be its founder, and his claim is no

idle boast. Of course, human beings had been arguing, and detecting

fallacies in other people’s arguments, since human society began; as John

Locke said, ‘God did not make men barely two legged and leave it to

Aristotle to make them rational.’ None the less, it is to Aristotle that we

owe the Wrst formal study of argumentative reasoning. But here as else-

where, there is Wrst of all a debt to Plato to be acknowledged. Following the

lead of Protagoras, Plato made important distinctions between parts of

speech, distinctions that form part of the basis on which logic is built. In

the Sophist he introduces a distinction between nouns and verbs, verbs being

signs of actions, and names being signs of the agents of those actions. A

sentence, he insists, must consist of at least one noun and at least one verb:

two nouns in succession, or two verbs in succession, will never make a

sentence. ‘Walks runs’ is not a sentence, nor is ‘Lion stag’. The simplest

kind of sentence will be something like ‘A man learns’ or ‘Theaetetus Xies’,

and only something with this kind of structure can be true or false (Sph.

262a–263b). The splitting of sentences into smaller units—of which this is

only one possible example—is an essential Wrst step in the logical analysis

of argument.

Aristotle left a number of logical treatises, which are traditionally placed

at the beginning of the corpus of his works in the following order:

Categories, de Interpretatione , Prior Analytics, Posterior Analytics, Topics , Sophistical

Refutations. This order is neither the one in which the works were written

nor the one in which it is most fruitful to read them. It is best to begin with

the consideration of the Prior Analytics, the most substantial and the least

controversial of his contributions to the discipline of logic which he

founded.

Aristotle’s Syllogistic

The Prior Analytics is devoted to the theory of the syllogism, a central

method of inference that can be illustrated by familiar examples such as

Every Greek is human.

Every human is mortal.

Therefore, Every Greek is mortal.

Aristotle sets out to show how many forms syllogisms can take, and which

of them provide reliable inferences.

For the purposes of this study, Aristotle introduced a technical vocabu-

lary which, translated into many languages, has played an important

part in logic throughout its history (1. 1. 24a10–b15). The word ‘syllogism’

itself is simply a transliteration into English of the Greek word ‘syllogismos’

which Aristotle uses for inferences of this pattern. It is deWned at the

beginning of the Prior Analytics: a syllogism is a discourse in which

from certain things laid down something diVerent follows of necessity

(1. 1. 24b18).

The example syllogism above contains three sentences in the indicative

mood and each such sentence is called by Aristotle a proposition (protasis): a

proposition is, roughly speaking, a sentence considered in respect of its

logical features. The third of the propositions in the example—the one

preceded by ‘therefore’—is called by Aristotle the conclusion of the syllogism.

The other two propositions we may call premisses, though Aristotle does not

have a consistent technical term to diVerentiate them.

The propositions in the above example begin with the word ‘every’: such

propositions are called by Aristotle universal propositions (katholou). They

are not the only kind of universal propositions: equally universal is a

proposition such as ‘No Greeks are horses’; but whereas the Wrst kind

of proposition was a universal aYrmative (kataphatikos), the second is a univer-

sal negative (apophatikos).

117

LOGIC