Kenny Anthony. Ancient Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy Volume 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

moneylending institution) and homonymy of a more interesting kind,

which his followers called ‘analogy’ (NE 1. 6. 1096a27 V.). His standard

example of an analogical expression is ‘medical’: a medical man, a medical

problem, and a medical instrument are not all medical in the same way.

However, the use of the words in these diVerent contexts is not a mere

pun: medicine, the discipline that is practised by the medical man, provides

a primary meaning from which the others are derived (EE 7. 2. 1236 a15–22).

Aristotle made use of this doctrine of analogy in a variety of ethical and

metaphysical contexts, as we shall see.

In Aristotle’s logical writings we Wnd two diVerent conceptions of the

structure of a proposition and the nature of its parts. One conception can

trace its ancestry to Plato’s distinction between nouns and verbs in the

Sophist. Any sentence, Plato there insisted, must consist of at least one verb

and one noun (262a–263b). It is this conception of a sentence as constructed

from two quite heterogeneous elements that is to the fore in Aristotle’s

Categories and de Interpretatione. This conception of propositional structure has

also been paramount in modern logic since the time of Gottlob Frege, who

made a sharp distinction between words that name objects, and predicates

that are true or false of objects.

In the syllogistic of the Prior Analytics the proposition is conceived in quite

adiVerent way. The basic elements out of which it is constructed are terms:

elements that are not heterogeneous like nouns and verbs, but that can

occur indiVerently, without change of meaning, either as subjects or as

predicates.5 To be sure, two terms in succession (like ‘man animal’) do not

compose a sentence: other elements, a quantiWer and a copula, such as ‘is’,

must enter in if we are to have a proposition capable of occurring in a

syllogism, such as ‘Every man is an animal’. Aristotle shows little interest in

the copula, and his attention now focuses on the quantiWers and their

relations to each other. The features that diVerentiate subjects from

predicates drop out of consideration.6

One of the dysfunctional features of the doctrine of terms is that it

fosters confusion between signs and what they signify. When Plato talks

5 Cf. 43a25–31. Instead of a distinction between noun and verb we here have a distinction

between proper names (which are not predicates but of which things are predicated) and terms

(which are both predicates and predicated of).

6 Modern admirers of Frege naturally regard the theory of terms as a disaster for the

development of logic. Peter Geach has written, ‘Aristotle was logic’s Adam; and the doctrine

of terms was Adam’s fall’ (Logic Matters (Oxford: Blackwell, 1972), 290).

128

LOGIC

about nouns and verbs, he makes quite clear that he is talking about signs.

He clearly distinguishes between the name ‘Theaetetus’ and the person

Theaetetus whose name it is; and he is at pains to point out that the

sentence ‘Theaetetus Xies’ can occur even though what it tells us, namely

the Xying of Theaetetus, is not among the things there are in the world. It

takes him some trouble to bring out the distinction between signs and

signiWed, because of the lack of inverted commas in ancient Greek. This

valuable device of modern languages makes it easy for us to distinguish the

normal c ase where we are using a word to talk about what it signiWes, and

the special case in which we are mentioning a word to talk about the word

itself, as in ‘ ‘‘Theaetetus’’ is a name’. The doctrine of terms, on the other

hand, makes it all too easy to confuse use wit h mention.

Take a syllogism whose premisses are ‘Every human is mortal’,

‘Every Greek is human’. Shall we say, as Aristotle’s language sometimes

suggests, (e.g. APr.1.4.25b37–9) that here mortal is predicated of human,

and human is predicated of Greek? This does not seem quite right: what

occurs as a predicate is surely a piece of language, and so perhaps we

should say instead: ‘mortal’ is predicated of human and ‘human’ is predi-

cated of Greek. But then we seem to have four terms, not three, in our

syllogism, since ‘ ‘‘human’’ ’ is not the same as ‘human’. We cannot remedy

this by rephrasing the Wrst proposition thus: ‘mortal’ is predicated

of ‘human’. It is human beings themselves, not the words they use to

refer to themselves, that are mortal. There is no doubt that Aristotle

sometimes fell into confusion between use and mention; the wonder is

that, given the quicksand provided by the doctrine of terms, he did not do

so more often.

Aristotle on Time and Modality

A feature of propositions as discussed in the Categories and the de Interpretatione

is that they can change their truth-values. At Cat.1.5.4a24, when discussing

whether it is peculiar to substances to be able to take on contrary proper-

ties, he says ‘The same statement seems to be both true and false. If, for

example, the statement that somebody is sitting is true, after he has stood

up that same statement will be false.’ According to a common modern

conception of the nature of the proposition, no proposition can be at one

129

LOGIC

time true and at another false. A sentence such as ‘Theaetetus is sitting’,

which is true when Theaetetus is sitting, and false at another time, would

on this view be said to express a diVerent proposition at diVerent times, so

that at one time it expresses a true proposition, and at another time a false

one. And a sentence asserting that ‘Theaetetus is sitting’ was true at time t is

commonly treated as asserting that the proposition that ascribes sitting at

time t to Theaetetus is true timelessly. On this account, no proposition is

signiWcantly tensed, but any proposition expressed by a tensed sentence

contains an implicit reference to time and is itself timelessly true or false.

Aristotle nowhere puts forward such a theory according to which tensed

sentences are incompletely explicit expressions of timeless propositions. For

him uttered sentences do indeed express something other than themselves,

namely thoughts in the mind; but thoughts change their truth-values just

as sentences do (Cat.1.5.4a26–8).7 For Aristotle, a sentence or proposition

such as ‘Theaetetus is sitting’ is signiW cantly tensed, and is at some times

true and at others false. It becomes true whenever Theaetetus sits down,

and becomes false whenever Theaetetus ceases to sit.

There is, for Aristotle, nothing in the nature of the proposition as such

that prevents it from changing its truth-value: but there may be something

about the content of a particular proposition that entails that its truth-

value m ust remain Wxed.

Logicians in later ages regularly distinguished between propositions that

can, and propositions that cannot, change their truth-value, calling the

former contingent and the latter necessary propositions. The roots of this

distinction are to be found in Aristotle, but he speaks by preference of

predicates, or properties, necessarily or contingently belonging to their

subjects. In both the de Interpretatione and the Categories he discusses propos-

itions such as ‘A must be B’ and ‘A can be not B’: propositions later called

by logicians ‘modal propositions’.

In the de Interpretatione he introduces the topic of modal propositions by

saying that whereas ‘A is not B’ is the negation of ‘A is B’, ‘A can be not B’ is

not the negation of ‘A can be B’. A piece of cloth, for instance, has the

possibility of being cut, but it also has the possibility of being uncut.

However, contradictories cannot be true together. Hence the negation of

‘A can be B’ is not ‘A can be not B’ but rather ‘A cannot be B’. In the

7 The truth-value of a proposition is its truth or its falsity, as the case may be.

130

LOGIC

straightforward categorical statement, whether we take the ‘not’ as going

with the ‘is’ or the ‘B’ makes no practical diVerence. In the modal

statement, whether we take the ‘not’ as going with the ‘can’ or the ‘B’

makes a great diVerence. Aristotle likes to bring out this diVerence by

rewriting ‘A can be B’ as ‘It is possible for A to be B’, rewriting ‘A can be not

B’ as ‘It is possible for A to be not B’, and rewriting ‘A cannot be B’ as ‘It is

not possible for A to be B’ (Int. 12. 21a37–b24). This rewriting allows the

negation sign to be unambiguously placed, and brings out the relationship

between a modal proposition and its negation.

Modal expressions other than ‘possible’, such as ‘impossible’ and ‘neces-

sary’, are to be treated similarly. The negation of ‘It is impossible for A to be

B’ is not ‘It is impossible for A not to be B’ but ‘It is not impossible for A to be B’;

the negation of ‘It is necessary for A to be B’ is not ‘It is necessary for A to

be not B’ but ‘It is not necessary for A to be B’ (Int . 13. 22a2–10).

These modal notions are interrelated. ‘Impossible’ is obviously enough

the negation of ‘possible’, but more interestingly ‘necessary’ and ‘possible’

are interdeWnable. What is necessa ry is what is not possible not to be, and

what is possible is what is not necessary not to be. If it is necessary for A to

be B, then it is not possible for A not to be B, and vice versa. Moreover, if

something is necessary, then a fortiori it is possible, and if it is not possible,

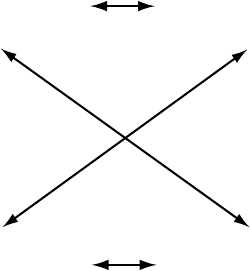

then a fortiori it is not necessary. Aristotle arranges the diVerent cases in a

square of opposition similar to that I exhibited above for categorical

propositions.

It is necessary for A to be B It is necessary for A not to be B

It is impossible for A not to be B It is impossible for A to be B

It is possible for A to be B It is possible for A not to be B

It is not necessary for A not to be B It is not necessary for A to be B

131

LOGIC

In each corner of this diagram the pairs of propositions are equivalent

to each other: this brings out the interdeWnability of the modal terms.

The operators ‘necessary’, ‘possible’, and ‘impossible’ in this square of

opposition are related to each other in a way parallel to the quantiWers

‘all’, ‘some’, and ‘no’ in the categorical square of opposition. As in the

categorical case, the propositions in the upper corners are contra ries: they

cannot both be true together, but they can both be false together. Pr opos-

itions in one corner are the contradictories of propositions in the diagonally

opposite corner. The pair of propositions in the upper corners entail the pair

of propositions immediately below them, but not conversely. Propositions

in the lower corners are compatible with each other: they can both be true

together, but they cannot both be false together (Int. 13. 22a14–35).

In this scheme all necessary propositions are also possible, though

the converse is not true. There is, however, as Aristotle remarks, another

use of ‘possible’ in which it is contrasted with ‘necessary’ and inconsistent

with it. In this other use, ‘It is possible that A is not B’ is not just consistent

with ‘It is possible that A is B’ but actually follows from it (Int. 12. 21b35). In

this use ‘possible’ would be equivalent to ‘neither necessary nor impossible’.

There is another word, ‘contingent’ (endechomenon), which is available

to replace ‘possible’ in this second use, and Aristotle often uses it for

that purpose (e.g. Apr. 1. 13. 32a18–21; 15. 34b25). Thus propositions can

be divided into three classes: the necessa ry, the impossible, and between

the two, the contingent (i.e. those that are neither necessary nor impos-

sible).

One of the most interesting passages in Aristotle’s Organon is the ninth

chapter of the de Interpretatione, in which he discusses the relation between

tense and modality in propositions. He begins by saying that for what is and

what has been, it is necessary that the afWrmati on or the negation should be

true or false (18a27–8). It transpires that he is not saying simply that if ‘p ’isa

present- or past-tense proposition, then ‘Either p or not p’ is necessarily

true: that is something that holds of all propositions, no matter what their

tense (19a30). Nor is he saying just that if ‘p’ is a present- or past-tense

proposition, it is either true or false: it turns out later that he thinks this is

true also of future-tense propositions. What he is saying is that if ‘p’isa

present- or past-tense proposition, then ‘p’ is a necessary proposition. The

necessity in question is clearly not logical necessity: it is not a matter of

logic that Queen Anne is dead. The necessity is the kind of necessity that is

132

LOGIC

expressed in the proverbs that what’s done cannot be undone, and that it is

no use crying over spilt milk (cf. NE 6. 2. 1139b7–11).

The central part of de Interpretatione 9 is an inquiry into whether this kind

of necessity that applies to present and past propositions applies also to all

future propositions . There are, no doubt, universally necessary truths that

apply to the future as well as to the present and to the past: but Aristotle’s

attention focuses on singular propositions such as ‘This coat will be cut up

before it wears out’, ‘There will be a sea-battle tomorrow’. The truth or

falsity of such propositions is not, on the face of it, entailed by any universal

generalization.

However, it is possible to construct a powerful argument to the eVect

that such a proposition about the future, if it is true, is necessarily true. If

A says that there will be a sea-battle tomorrow, and B says that there will

not be, then one or other will be speaking the truth. Now there are

relations between propositions in diVerent tenses: for instance, if ‘Socrates

will be white’ is now true, then ‘Socrates will be white’ has been true in the

past, a nd indeed was always true in the past. So—the argument goes—

If it was always true to say it is or will be, then it is impossible for that not to be or

to be going to be. But if it is impossible for something not to come about, then it

cannot not come about. But if it cannot not come about, then it is necessary for

it to come about. Therefore everything that is going to come about is, of necessity,

to come about. (9. 18b11–25)

The argument that Aristotle is considering began by supposing that

someone says, for example, ‘There will be a sea-battle tomorrow’ and

someone else ‘There will not be a sea-battle tomorrow’ and pointing out

that one or the other is speaking truly. But, he goes on, a similar prediction

might have been made long ago, ‘There will be a sea-battle ten thousand

years hence’, and this too, or its contradictory, will be true. Indeed, it

makes no diVerence whether any prediction has ever been made. If in the

whole of time either the proposition or its contradictory has been the

truth, it was necessary for the thing to come about. Since of whatever

happens ‘It will happen’ was always previously true, everything must

happen of necessity (9. 18b26–19a5).

It will follow, Aristotle says, that nothing is a matter of chance or

happenstance. Worse, there will be no point in deliberating and choosing

between alternatives. But in fact, he says, there are many obvious examples

133

LOGIC

of things turning out one way when they could have turned out another,

like a cloak that could have been cut up but wore out Wrst. ‘So it is clear

that not everything is or happens of necessity, but some things are a matter

of happenstance, and the afWrmation is not true rather than the negation;

and with other things one is true rather and for the most part, but still it is

open for either to happen and the other not’ (9. 19a18–22).

How then are we to deal with the argument to the eVect that everything

happens of necessity? Because Aristotle says that in some cases ‘the afWrma-

tion is not true rather than the negation’, some have thought that his

solution was that future contingent propositions lack a truth-value: not

only are they not necessarily true or false, they are not true or false at all.

However, this can hardly be what he means; for at 18b17 he says that it is

not open to us to say that neither ‘It will be the case that p’ nor ‘It will not

be the case that p’ is true. One reason he gives for this is that it is obviously

impossible that they should both be false; but that does not rule out their

both having some third value. His argument to rule this out is not

altogether clear, but it appears to be something like this: if neither ‘There

will be a sea-battle tomorrow’ nor ‘There will not be a sea-battle tomorrow’

is true today, then neither ‘There is a sea-battle today’ nor ‘There is not a

sea-battle today’ will be true tomorrow.

At the end of the discussion it seems clear that Aristotle accepts that

future contingent propositions can be true, but that they are not necessary

in the way that present and past propositions are. Everything is necessary-

when-it-is, but that does not mean it is necessary, period. It is necessary

that there should or should not be a sea-battle tomorrow, but it is not

necessary that there should be a sea-battle and it is not necessary that there

should not be a sea-battle (9. 19a30–2).

What is less clear is how Aristotle disarms the powerful argument he

built up in favour of universal necessity. The distinction just enunciated is

not sufWcient by itself to do so, for it does not take account of the appeal to

the past truth of future contingents that was part of the argument. Since

on his own admission the past is necessary, past truths about future events

must be necessary, and therefore the future events themselves must be

necessary. The solution must come through an analysis of the notion of

past truths: we must distinguish between truths that are stated in the past

tense, and truths that are made true by events in the past. ‘It was true ten

thousand years ago that there was going to be a sea-battle tomorrow’, for

134

LOGIC

all its past tense, is not really a proposition about the past. But this solution

is nowhere clearly enunciated by Aristotle, and the problem he set out

recurred in many diVerent forms in later antiquity and in the Middle Ages.8

In the Prior Analytics Aristotle explores the possibility of c onstructing

syllogisms out of modal propositions. His attempt to construct a modal

syllogistic is nowadays universally regarded as a gallant failure; and even in

antiquity its faults were realized. His successor Theophrastus worked on it

and improved it, but even so it must be regarded as unsatisfactory. The

reason for the lack of success has been well explained by Martha Kneale: it

is Aristotle’s indecision about the best way to analyse modal propositions.

If modal words modify predicates, there is no need for a special theory of modal

syllogisms. For these are only ordinary assertoric syllogisms of which the premises

have peculiar predicates. On the other hand, if modal words modify the whole

statements to which they are attached, there is no need for a special modal

syllogistic, since the rules determining the logical relations between modal state-

ments are independent of the character of the propositions governed by the modal

words.9

The necessary basis for a modal logic, she concludes, is a logic of unana-

lysed propositions such as was developed by the Stoics. This statement

needs qualiWcation. It is true that the Xowering of modal logic in the

twentieth century depended on just such a propositional calculus. But

there were also signiWcant developments in modal logic in the Middle Ages

within an Aristotelian context, when Aristotle’s own modal syllogistic was

superseded by much more sophisticated systems. Again, not all propos-

itions in which words such as ‘can’ and ‘must’ occur within the predicate

can be replaced by propositions in which the modal operator attaches to an

entire nested proposition. ‘I can speak French’, for instance, does not have

the same meaning as ‘It is possible that I am speaking French’. Aristotle

makes a distinction between two-way possibilities (such as a man’s ability to

walk, or not to walk, as he chooses) and one-way possibilities (Wre can burn

8 This passage of the de Interpretatione has also been the subject of voluminous discussion in

modern times. My interpretation owes a lot to that of G. E. M. Anscombe, whose ‘Aristotle and

the Sea-Battle’ of 1956 (From Parmenides to Wittgenstein (Oxford: Blackwell, 1981) ) is still, nearly Wfty

years on, one of the best commentaries on the passage. For a carefully argued alternative

account, see S. Waterlow, Passage and Possibility: A Study of Aristotle’s Modal Concepts (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1982), 78–109.

9 Kneale and Kneale, The Development of Logic, 91.

135

LOGIC

wood, and if it has wood placed on it, it will burn it, and there are no two

ways about it) (Int.22b36–23a11). The logic of the two-way abilities exercised

in human choice has not, to this day, been adequately formalized.

Stoic Logic

In the generation after Aristotle modal logic was developed in an interest-

ing way in the school of Megara. For Diodorus Cronos a proposition is

possible iV it either is or will be true, is impossible iV it is false and will never

be true, and is necessary iV it is true and will never be false.10 Diodorus, like

Aristotle, accepted that propositions were fundamentally tensed and could

change their truth-values; but unlike Aristotle he does not need to make a

sharp distinction between actuality and potentiality, since potentialities are

deWned in terms of actualities. Propositions, on Diodorus’ deWnitions,

change not only their truth-values but also their modalities. ‘The Persian

Empire has been destroyed’ was untrue but possible when Socrates was

alive; after Alexander’s victories it was true and necessary (LS 38e). For

Diodorus, as for Aristotle, a special necessity applies to the past.

It is a feature of Diodor us’ deWnition of possibility that there are

no possibilities that are forever unrealized: whatever is possible is or will

be one day true. This appears to involve a form of fatalism: no one can ever

do anything other than what they in fact do. Diodorus seems to have

supported this by a line of reasoning that became known (we know not

why) as the Master Argument. Starting from the premiss (1) that

past truths are necessary, Diodorus oVered a proof that nothing is possible

that neither is nor will be true. Let us suppose (taking an example used

in ancient discussions of the argument) that there is a shell in shallow

water, let us call it Nautilus, which will never in fact be seen. We can

construct an argument from this premiss to show that it is impossible for

it to be seen.

(2) Nautilus will not ever be seen.

(3) It has always been the case that

Nautilus will not ever be seen. (a plausible consequence of (2))

10 ‘IV ’ is a logician’s abbreviation for ‘if and only if ’.

136

LOGIC

Chrysippus, greatest of Stoic logicians, in a statue in the Louvre (third century ad)