Kenny Anthony. Ancient Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy Volume 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

of change as the passage from potentiality to actuality, whether (as in

substantial change) from matter to form or (as in accidental change) from

one to another quality of a substance. These technical notions, which he

employed in such an astonishing variety of contexts, will be examined in

detail in later chapters.

Aristotle’s vision of the cosmos owes much to his Presocratic precursors

and to Plato’s Timaeus. The earth was in the centre of the universe: around it

a succession of concentric crystalline spheres carried the moon, the sun,

and the planets in their journeys around the visible sky. The heavenly

bodies were not compounds of the four terrestrial elements, but were

made of a superior Wfth element or quintessence. They had so uls as well as

bodies: living supernatural intellects, guiding their travels through the

cosmos. These intellects were movers which were themselves in motion,

and behind them, Aristotle argued, there must be a source of movement

not itself in motion. The only way in which an unchanging, eternal mover

could cause motion in other beings was by attracting them as an object of

love, an attraction which they express by their perfect circular motion. It is

thus that Dante, in the Wnal lines of his Paradiso, Wnds his own will, like a

smoothly rotating wheel, caught up in the love that moves the sun and all

the other stars.

Even the best of Aristotle’s scientiWc work has now only a historical

interest. The abiding value of treatises such as his Physics is in the philo-

sophical analyses of some of the basic concepts that pervade the physics of

diVerent eras, such as space, time, causation, and determinism. These are

examined in detail in Chapter 5. For Aristotle biology and psychology were

parts of natural philosophy no less than physics and chemistry, since they

too studied diVerent forms of physis, or nature. The biological works we have

already looked at; the psychological works will be examined more closely

in Chapter 7.

The Aristotelian corpus, in addition to the systematic scientiWc treatises,

contains a m assive collection of occasional jottings on scientiWc topics, the

Problems. From its structure this appears to be a commonplace book in

which Aristotle wrote down provisional answers to questions that were put

to him by his students or corresponde nts. Because the questions

are grouped rather haphazardly, and often appear several times—and are

sometimes given diVerent answers—it seems unlikely that they were

generated by Aristotle himself, whether as a single series or over a lifetime .

88

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

But the collection contains many fascinating details that throw insight into

the workings of his omnivorous intellect.

Some of the questions are the kind of thing a patient might bring to a

doctor. Ought drugs to be used, rather than surgery, for sores in the

armpits and groin? (1. 34. 863a21). Is it true that purslane mixed with salt

stops inXammation of the gums? (1. 38. 863b12). Does cabbage really cure a

hangover? (3. 17. 873b1). Why is it diYcult to have sex under water? (4. 14.

878a35). Other question s and answers make us see Aristotle more in the role

of agony aunt. How should one cope with the after-eVects of eating garlic?

(13. 2. 907 b 28–908a10). How does one prevent biscuit from becoming hard?

(21. 12. 928a12). Why do drunken men kiss old women they would never

kiss when sober? (30. 15. 953b15). Is it right to punish more seriously thefts

from a public place than thefts from a private house? (29. 14. 952 a16). More

seriously, why is it more terrible to kill a woman than a man, although the

male is naturally superior to the female? (29. 11. 951a12).

A whole book of the Problems (26) is devoted essentially to weather

forecasting. Other books contain questions that simply reXect general

curiosity. Why does the noise of a saw being sharpened set our teeth on

edge? (7. 5. 886b10). Why do humans not have manes? (10. 25. 893b17). Why

do non-human animals not sneeze or squint? (Don’t they?) (10. 50. 896b5; 54.

897a1). Why do barbarians and Greeks alike count up to ten? (15. 3. 910b23).

Why is a Xute better than a lyre as an a ccompaniment to a solo voice? (19. 43.

922a1). Very often, the Problems ask ‘Why is such and such the case?’ when a

more appropriate question would have been ‘Is such and such the case?’ For

instance, Why do Wshermen have red hair? (37. 2. 966 b 25). Why does a large

choir keep time better than a small one? (19. 22. 919a36).

The Problems let us see Aristotle with his hair down, rather like the table

talk of later writers. One of his questions is particularly endearing to those

who may have found it hard to read their way through his more diYcult

works: Why is it that some people, if they begin to read a serious book, are

overcome by sleep even against their will? (18. 1. 916b1).

The Legacy of Aristotle and Plato

When Alexander the Great died in 323, democratic Athens became uncom-

fortable even for an anti-imperialist Macedonian. Saying that he did not

89

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

wish the city that had executed Socrates ‘to sin twice against philosophy’,

Aristotle escaped to Chalcis, where he died in the following year. His will,

which survives, makes thoughtful provision for a large number of friends

and dependants. His library was left to Theophrastus, his successor as head

of the Lyceum. His own papers were vast in size and scope—those that

survive today total around a million words, and it is said that we possess

only one-Wfth of his output. As we have seen, in addition to philosophical

treatises on logic, metaphysics, ethics, aesthetics, and politics, they included

historical works on constitutions, theatre and sport, and scientiWc works

on botany, zoology, biology, psychology, chemistry, meteorology, astron-

omy, and cosmology.

Since the Renaissance it has been traditional to regard the Academy and

the Lyceum as two opposite poles of philosophy. Plato, according to this

tradition, was idealistic, utopian, other-worldly; Aristotle was realistic,

utilitarian, commonsensical. Thus, in Raphael’s School of Athens Plato, wear-

ing the colours of the volatile elements air and Wre, points heavenwards;

Aristotle, clothed in watery blue and earthy green, has his feet Wrmly on

the ground. ‘Every man is born an Aristotelian or a Platonist,’ wrote

S. T. Coleridge. ‘They are the two classes of men, besides which it is

next to impossible to conceive a third.’ The philosopher Gilbert Ryle in

the twentieth century improved on Coleridge. Men could be divided

into two classes on the basis of four dichotomies: green versus blue,

sweet versus savoury, cats versus dogs, Plato versus Ari stotle. ‘Tell me

your preference on one of these pairs’, Ryle used to say, ‘and I will tell

you your preference on the other three.’8

In fact, as we have already seen and will see in greater detail later, the

doctrines that Plato and Aristotle share are more important than those

that divide them. Many post-Renaissance historians of ideas have been less

perceptive than the many commentators in late antiquity who saw it as

their duty to construct a harmonious concord between the two greatest

philosophers of the ancient world.

It is sometimes said that a philo sopher should be judged by the import-

ance of the questions he raises, not the correctness of the answers he gives.

If that is so, then Plato has an uncontestable claim to pre-eminence as a

philosopher. He was the Wrst to pose questions of great profundity, many of

8 Preference for an item on the left of a pair was supposed to go with preference for the other

leftward items, and similarly for rightward preferences.

90

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

which remain open questions in philosophy today. But Aristotle too can

claim a signiWcant contribution to the intellectual patrimony of the world.

For it was he who invented the concept of Science as we understand it

today and as it has been understood since the Renaissance.

First, he is the Wrst person whose surviving works show detailed obser-

vations of natural phenomena. Secondly, he was the Wrst philosopher to

have a sound grasp of the relationship between observation and theory in

scientiWc method. Thirdly, he identiW ed and classiWed diVerent scientiWc

disciplines and explored their relationships to each other: the very concept

of a distinct discipline is due to him. Fourthly, he is the Wrst professor to

have organized his lectures into courses, and to have taken trouble over

their appropriate place in a syllabus (cf. Pol. 1. 10. 1258a20). Fifthly, his

Lyceum was the Wrst research institute of which we have any detailed

knowledge in which a number of scholars and investigators joined in

collaborative inquiry and documentation. Sixthly, and not least important,

he was the Wrst person in history to build up a research library—not simply

a handful of books for his own bookshelf, but a systematic collection to be

used by his colleagues and to be handed on to posterity.9 For all these

reasons, every academic scientist in the world today is in Aristotle’s debt.

He well deserved the title he was given by Dante: ‘the master of those who

know’.

Aristotle’s School

Theophrastus (372–287), Aristotle’s ingenious successor as head of the

Lyceum, continued his master’s researches in several ways. He wrote

extensively on botan y, a discipline that Aristotle had touched only lightly.

He improved on Ari stotle’s modal logic, and anticipated some later Stoic

innovations. He disagreed with some fundamental principles of Aristotle’s

cosmology, such as the nature of place and the need for a motionless

mover. Like his master, he wrote copiously, and the mere list of the titles of

his works takes up sixteen pages in the Loeb edition of his life by Diogenes

Laertius. They include essays on vertigo, on honey, on hair, on jokes, and

on the eruption of Etna. The best known of his surviving works is a book

9 See L. Casson, Libraries in the Ancient World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 28–9.

91

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

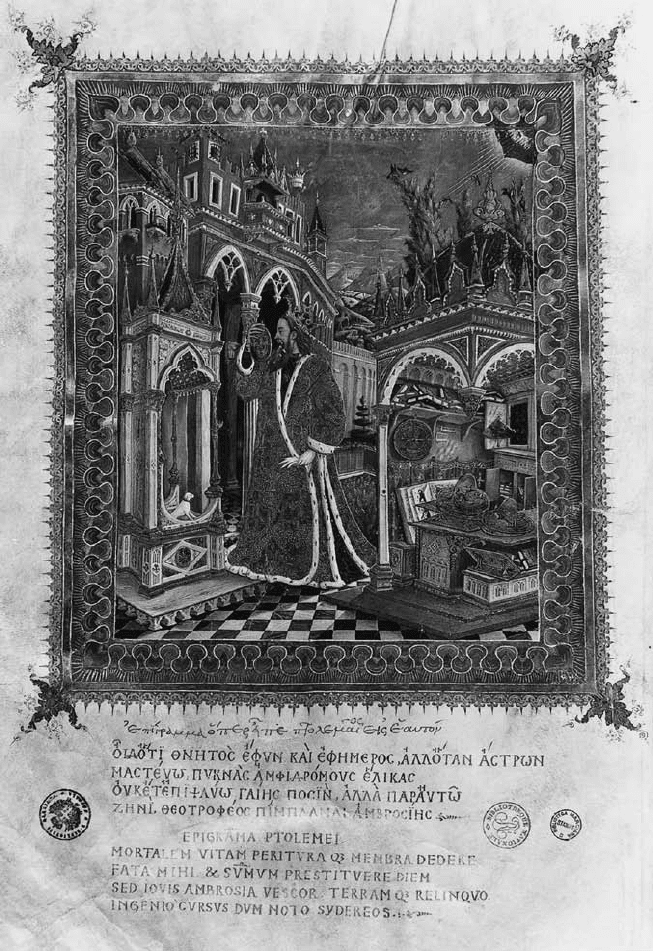

A Venetian representation of King Ptolemy and his library at Alexandria

entitled Characters, modelled on Aristotle’s delineation in his Ethics of

individual virtues and vices, but sketching them with greater reWnement

and with a livelier wit. He was a diligent historian of philosophy, and the

part of his doxography that survives, On the Senses, is one of our main sources

for Presocratic theories of sensation.

One of Theophrastus’ pupils, Demetrius of Phaleron, was an adviser to

one of Alexander’s generals, Ptolemy, who made himself king of Egypt in

305. It is possible that it was he who suggested the creation in the new city

of Alexandria of a library modelled on that of Aristotle, a project that was

carried out by Ptolemy’s son Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The history of

Aristotle’s own library is obscure. On Theophrastus’ death it seems to

have been inherited not by the next head of the Lyceum, the physicist

Strato, but by Theophrastus’ nephew Neleus of Skepsis, one of the last

surviving pupils of Aristotle himself. Neleus’ heirs are said to have hidden

the books in a cave in order to prevent them from being conWscated by

agents of King Eumenes, who was building up a library at Pergamon to rival

that of Alexandria. Rescued by a bibliophile and taken to Athens, the story

goes, the books were conWscated by the Roman general Sulla when he

captured the city in 86 bc, and shipped to Rome, where they were Wnally

edited and published by Andronicus of Rhodes around the middle of the

Wrst century bc (Strabo 609–9; Plutarch, Sulla 26).10

Every detail of this story has been called in question by one or another

scholar,11 but if true it would account for the oblivion that overtook

Aristotle’s writings between the time of Theophrastus and that of Cicero.

It has been well said that ‘If Aristotle could have returned to Athens in 272

bc, on the Wftieth anniver sary of his death, he would hardly have recog-

nized it as the intellectual milieu in which he had taught and researched

for much of his life.’12

It was not that philosophy at that date was dormant in Athens: far from

it. Though the Lyceum under Strato was a shadow of itself, and the

10 Puzzlingly, our best ancient catalogue of the Andronican edition appears to have been

made by a librarian at Alexandria. Is it possible that Mark Antony acquired the corpus from an

heir of the proscribed Sulla and shipped them oV to Cleopatra to Wll the gaps in her recently

destroyed library, just as her earlier lover Julius Caesar had pillaged the Pergamum library for

her beneWt?

11 See J. Barnes, in J. Barnes and M. GriYn, Philosophia Togata, vol. ii (Oxford: Clarendon Press,

1997), 1–23.

12 Introd. to LS, 1.

93

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

Platonic Academy under its new head Arcesilaus had given up metaphysics

in favour of a narrow scepticism, there were two Xourishing new schools of

philosophy in the city. The best-known philosophers in Athens were

members neither of the Academy nor of the Lyceum, but were the

founders of these new schools: Epicurus, who established a school

known as The Garden, and Zeno of Citium, whose followers were called

Stoics because he taught in the Stoa, or painted portico.

Epicurus

Epicurus was born into a family of Athenian expatriates in Samos, and paid

a brief visit to Athens in the last year of Aristotle’s life. During early travels

he studied under a follower of Democritus, and established more than one

school in the Greek islands. In 306 he set up house in Athens and lived

there until his death in 271. His followers in the Garden included women

and slaves; they lived in seclusion and ate simple fare. He wrote 300 books,

we are told, but all that survive intact are three letters and two groups of

maxims. His philosophy of nature is set out in a letter to Herodotus and a

letter to Pythocles; in the third letter, to Menoecus, he summarizes his

moral teaching. The Wrst set of maxims, forty in number, has been

preserved, like the three letters, in the life of Epicurus by Diogenes Laertius:

it is called Kyriai Doxai, or major doctrines. Eighty-one similar aphorisms

were discovered in a Vatican manuscript in 1888. Fragments from Epicurus’

lost treatise On Nature were buried in volcanic ash at Herculaneum when

Vesuvius erupted in ad 79. Painstaking eVorts to unroll and decipher them,

begun in 1800, continue to the present day. But for most of our knowledge

of his teachings, however, we depend on the surviving writings of his

followers, especially a much later writer, the Latin poet Lucretius.

The aim of Epicurus’ philosophy is to make happiness possible by

removing the fear of death, which is the greatest obstacle to tranquillity.

Men struggle for wealth and power so as to postpone death; they throw

themselves into frenzied activity so that they can forget its inevitability. It is

religion that causes us to fear death, by holding out the prospect of

suVering after death. But this is an illusion. The terrors held out by religion

are fairy tales, which we must give up in favour of a scientiWc account of

the world.

94

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

This scientiWc account is taken mainly from Democritus’ atomism.

Nothing comes into being from nothing: the basic units of the world are

everlasting, unchanging, indivisible units or a toms. These, inWnite in

number, move about in the void, which is empty and inWnite space: if

there were no void, movement would be impossible. This motion had no

beginning, and initially all atoms move downwards at constant and equal

speed. From time to time, however, they swerve and collide, and it is from

the collision of atoms that everything in heaven and earth has come into

being. The swerve of the atoms allows scope for human freedom, even

though their motions are blind and purposeless. Atoms have no properties

other than shape, weight, and size. The properties of perceptible bodies are

not illusions, but they are supervenient on the basic properties of atoms.

There is an inWnite number of worlds, some like and some unlike our own

(Letter to Herodotus, D.L. 10. 38–45).

Like everything else, the soul consists of atoms, diVering from other

atoms only in being smaller and subtler; these are dispersed at death and

the soul ceases to perceive (Letter to Herodotus, D.L. 10. 63–7). The gods

too are built out of atoms, but they live in a less turbulent region, immune

to dissolution. They live happy lives, untroubled by concern for human

beings. For that reason belief in providence is superstition, and religious

rituals a waste of time (Letter to Menoecus, D.L. 10. 123–5). Since we are

free agents, thanks to the atomic swerve, we are masters of our own fate:

the gods neither impose necessity nor interfere with our choices.

Epicurus believed that the senses were reliable sources of information,

which operate by transmitting images from external bodies into the atoms

of our soul. Sense-impressions are never, in themselves, false, though we

may make false judgements on the basis of genuine appearances. If appear-

ances conXict (if, for instance, something looks smooth but feels rough)

then the mind must give judgement between these competing witnesses.

Pleasure, for Epicurus, is the beginning and end of the happy life. This

does not mean, however, that Epicurus was an epicure. His life and that of

his followers was far from luxurious: a good piece of cheese, he said, was as

good as a feast. Though a theoretical hedonist, in practice he attached

importance to a distinction he made between diVerent types of pleasure.

There is one kind of pleasure that is given by the satisfaction of our desires

for food, drink, and sex, but it is an inferior kind of pleasure, because it is

bound up with pain. The desire these pleasures satisfy is itself painful, and

95

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

its satisfaction leads to a renewal of desire. The pleasures to be aimed at are

quiet pleasures such as those of private friendship (Letter to Menoecus,

D.L. 10 . 27–32).

To his last, Epicurus insisted that for a philosopher pleasure, in any

circumstances, could outweigh pain. On his deathbed he wrote the

following letter to his friend Idomeneus: ‘I write this to you on the blissful

day that is the last of my life. Strangury and dysentery have set in, with the

greatest possible intensity of pain. I counterbalance them by the joy I have

in the memory of our past conversations’ (D.L. 10. 22). He lived up to his

conviction that death, though inescapable, is, if we take a truly philosoph-

ical view of it, not an evil.

Stoicism

Stoics, like Epicureans, sought tranquillity, but by a diVerent route. The

founder of Stoicism was Zeno of Citium (334–262 bc). Zeno was born in

Cyprus, but migrated to Athens in 313. He read Xenophon’s memoir of

Socrates, which gave him a passion for philosophy. He was told that the

nearest contemporary equivalent of Socrates was Crates the Cynic. Cyni-

cism was not a set of philosophical doctrines, but a way of life expressing

contempt for wealth and disdain for conventional propriety. Its founder

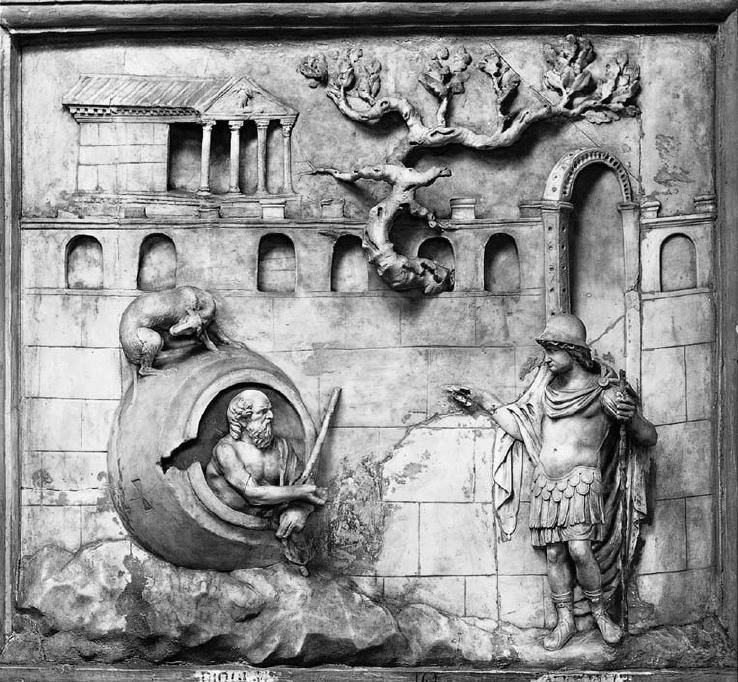

was Diogenes of Sinope, who lived like a dog (‘cynic’ m eans ‘dog-like’) in a

tub for a kennel, wearing coarse clothes and subsisting on alms. A contem-

porary of Plato, for whom he had no gr eat respect, Diogenes was famou s

for his snub to Alexander the Great. When the great man visited him and

asked, ‘What can I do for you’, Diogenes replied, ‘You can move out of my

light’ (D.L. 6. 38). Crates, impressed by Diogenes, gave his wealth to the

poor and imitated his bohemian lifestyle; but he was less misanthropic, and

had a keen sense of humour that he expressed in poetic satire.

Zeno was Crates’ pupil for a time, but he did not become a cynic and

drop out of society, though he avoided formal dinners and was fond of

basking in the sun. After some years as a student of the Academy, he set up

his own school in the Stoa Poikile. He instituted a systematic curriculum of

philosophy, dividing it into three main disciplines, logic, ethics, and phys-

ics. Logic, said his followers, is the bones of philosophy, ethics the Xesh, and

physics the soul (D.L. 7. 37). Zeno studied under the great Megarian

96

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE

logician Diodorus Cronos, and was a fellow pupil of Philo, who laid the

ground for a development of logic which marked, in some areas, an

improvement on Aristotle.13 He himself , however, was more interested in

ethics.

It may seem surprising that a moralist like Zeno should give physics the

highest place in the curriculum. But for Zeno, and later Stoics, physics is

the study of nature and nature is identiWed with God. Diogenes Laertius

tells us, ‘Zeno says that the whole world and heaven are the substance of

Alexander standing in Diogenes’ light (Rome, Villa Albani)

13 On Diodorus and Philo, see Ch. 3 below.

97

ARISTOTLE TO AUGUSTINE