Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Barrels and Buckets

50

Lopez, Robert S., and Irving W. Raymond . Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean

World. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

Weatherford, Jack. The History of Money. New York: Three Rivers Press, 1997.

Barrels and Buckets

Many of the kitchen utensils and containers in a medieval house were made

of wood. This was especially true in Northern Europe where oaks were com-

mon native trees. While Mediterranean craftsmen made many household

containers of pottery, English, French, and German coopers perfected the

barrel. English coopers formed their own guild around 1300, but cooper-

ing was a skilled craft going back to pagan times. Some ship burials, includ-

ing the best known at Sutton Hoo, preserved barrel hoops and even whole

barrels and buckets.

Milking buckets were made by coopers and had one stave standing up

higher than the rest as a handle. Water buckets needed handles or some

way to fasten to a shoulder yoke. Kitchens kept barrels for storing fl our

and wooden vats for pickling and ale brewing. Milk was churned to but-

ter in a narrow barrel fi tted with a lid—the butter churn. Another wooden

tub made cheese. Most houses used wooden bowls and wooden tankards.

Clothes washing used wooden tubs, sometimes an ale barrel cut in half.

Bathing required very large tubs that were also made by coopers using bar-

rel techniques. Commercial bathing tubs were the largest domestic-use

barrels, since they could fi t several people. All large vats and tubs had two

staves standing up higher than the rest as handles, with holes to allow a pole

to slide through and raise them up.

Barrels were made in straight and bulging forms for different purposes.

The basic craft is the same; it involves shaving wooden staves so they will fi t

together in a circle without gaps. When the shape is straight, as in a butter

churn, the cooper binds them tightly together with wooden or iron bands

and fastens a top and bottom. The wood does not need to be bent, only to

be shaved along its edges so it will fi t into the circle. Wooden buckets and

tubs were made this way, and they made up a large part of every household’s

containers. The traditional name for coopers who specialized in buckets and

tubs was white coopers because so many of their articles were used for milk

and cheese.

Barrels were used to ship not only ale and wine, but also oil, soap, and tar.

They were used to ship coins from the mint. They shipped eels and some

other kinds of fi sh, chiefl y salted herring. The herring trade in northern

Germany kept hundreds of coopers at work.

Dry coopers made barrels and casks for shipping dry goods such as fl our,

gunpowder, and fi sh. Some of the barrels had to be watertight, such as for

fi sh brine or soap, but others were only intended for transporting goods

Barrels and Buckets

51

and did not need to be made with care. These barrels used the cheapest wood

and thin staves that bent easily.

Coopers needed more care and skill to make barrels that bowed outward

in the middle and were watertight. They were known as wet coopers; their

barrels were made of the thickest wood and took much longer to make.

Alcoholic liquids were always put into thick barrels that could withstand the

chemical pressure of fermenting gasses. While many kinds of wood could be

used for other types of casks, those intended for wine and beer were nearly

always oak.

The cooper cut his staves and shaved them to taper at the ends, to have

slanted edges, and to be hollowed on one side. He also cut notches on the

inside surface at both ends. When his staves were ready, he used an iron

hoop to make the staves stand up in their fi rst circle formation. If he had

cut and shaved them correctly, they fi t tightly into the hoop. Wooden hoops

held the staves in place, and the wood had to be softened with boiling water

or steam. Then the cooper and his assistants placed a basket of fi re inside the

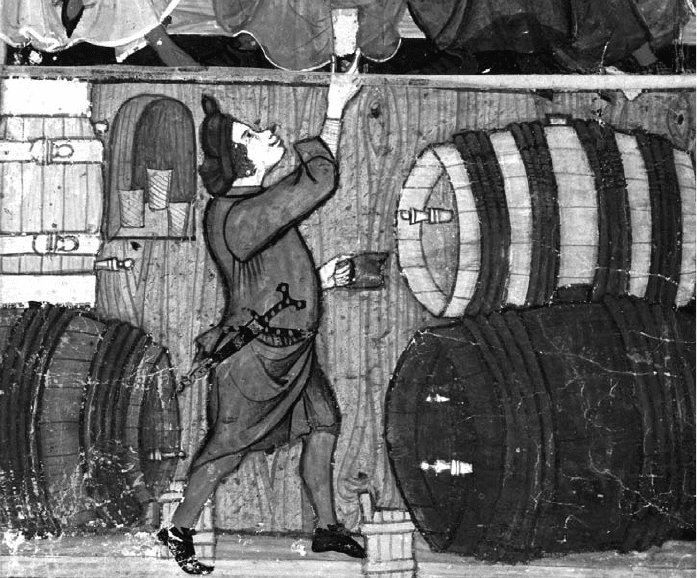

Barrels came in sizes specifi c to the wine, ale, or beer they contained. A good wine

cellar had many different barrels, butts, pipes, and casks.

(The British Library/StockphotoPro)

Barrels and Buckets

52

barrel, and, as the smoke poured out the top hole, they hammered wooden

and iron hoops onto the staves, forcing the barrel to curve around the tapers

of its staves. The staves heated and dried as they hammered, but if they had

been made well, they bent and did not split. When all the hoops were in

place, the barrel’s curved shape was fi nished.

The cooper then shaved the barrel smooth inside and out; a rough inner

surface collected bacteria and made ale spoil unless its alcohol content was

high. He made the fl at end covers (heads) by pegging staves together with

wooden dowels into two small solid boards. He cut them into the proper-

sized circles to fi t into the ends of the barrel and shaved them to have the

correct angles. The curved staves were now dry and would not change their

shape if the iron hoops were removed, so the end hoops (called chimes)

were loosened to let the round heads into their places. One by one, they

fi tted into the notches cut in the staves’ ends. A fi nished barrel had all

of its iron hoops hammered tightly into place. A well-made wine or beer

cask could be used for 50 years.

The last step was branding the barrel, no matter what size or purpose

it was meant to serve: bucket, churn, wine tun, ale fi rkin, or beer barrel.

Every cooper in the guild had his own branding iron to mark his bar-

rels. When a cooper died, his iron was immediately taken to the guildhall

so nobody could forge his mark on substandard barrels. It was illegal to

use unmarked barrels—since no cooper had certifi ed their legal size, they

were usually too small.

Barrels came in all sizes, and they had different names. Hogsheads, kegs,

butts, barrels, fi rkins, pipes, casks, tuns, and kilderkins were specifi c sizes

that were used in certain industries. Sweet wine was sold in butts, small bar-

rels holding only 18½ gallons, or in pipes, which were larger. Ale came in

30-gallon barrels and beer in 36-gallon barrels, the size that is most com-

mon today. Most wine came in casks, if not the larger wholesale tuns.

Since the industries that used these containers could not independently

measure the amount of liquid they poured in, they trusted the coopers to

make them correctly so customers would not be cheated. When coopers

used green wood, over time the barrels shrank and became illegal measure-

ments. By the middle of the 15th century, offi cials outlawed the use of un-

seasoned oak. Coopers were permitted to recycle old barrel staves as long as

they had not contained anything noxious like tar, soap, or oil. When barrels

wore out, coopers were able to fi x them.

Beginning in the 13th century, German coopers along the Rhine River

began competing to make the largest cask. It became a tradition, and the fi -

nal record was not set until the 18th century with the Heidelberg Tun,

which used more than 100 oak trees.

See also: Beverages, Hygiene, Kitchen Utensils, Weights and Measures.

Beekeeping

53

Further Reading

Kilby, Kenneth. The Cooper and His Trade. Fresno, CA: Linden Publishing, 1989.

Kilby, Kenneth. Coopers and Coopering. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publishing,

2008.

Baths. See Hygiene

Beekeeping

Beekeeping was a very important task in Europe’s Middle Ages, since honey

was the only good sweetener until sugar began to be imported. Sugar re-

mained extremely expensive, and honey, though mostly used by the wealthy,

was the only sweetener common people could even hope to taste. Bees-

wax was the only wax available for candles or for lost-wax casting of metal,

so it was equal to honey in importance. Keeping bees means capturing wild

hives and placing them in man-made structures, harvesting honey and wax,

and knowing how to care for the bees’ welfare.

When honeycombs are removed, the beekeeper must extract and clean

the honey and wax. A honeycomb’s many cells, fi lled with honey, are capped

with more wax by the bees to seal each hexagonal cell. In harvesting the

honey, the keeper must slice off this layer of wax and then drain the honey

into a pot. Modern beekeepers use a centrifuge to extract all the honey

from the wax cells, but in the Middle Ages, gravity was the only tool used—

the honey drained off, leaving behind the wax. The honey was then strained

through cheesecloth to remove dead bees or dirt. Good honey was clean;

Charlemagne’s estate instructions specifi cally directed that the highest stan-

dards be followed in processing honey, wax, and mead.

In early summer, bees often swarm, which means that a group of bees

suddenly leaves the hive and fl ies, with a queen, to a new location to build

a new hive. Beekeepers learned how to predict when a hive of bees was

going to swarm by observing the queen’s activity. Most early bee observ-

ers assumed the very large bee that never left the hive (except to swarm)

was a male and referred to it as a king. They assumed the worker bees were

females. The fi rst description of bees that correctly called the large bee a fe-

male and the workers males was published in 1586, during the early Renais-

sance, in Spain. All through the Middle Ages, the largest bee was known as

the king.

A beekeeper who wanted to control the location of his hives needed an

artifi cial hive for the bees to accept as their home. He also needed a basket

to trap the hive in; baskets were most often made of wicker, a woven net of

pliable branches. He might use a smoky torch to sedate the bees, and, by the

late Middle Ages, some beekeepers were using light cloth hoods and masks

to protect themselves.

Beekeeping

54

Southern Europe had already developed traditional methods of keep-

ing bees by the Middle Ages. Each region had its traditional form of hive.

The most common forms were wicker covered with mud, pottery, or boxes

made from wood or cork. Wicker hives, most often shaped like cones, were

called skeps. Each needed to have a hole for the bees to go in and out and

a larger hole for the beekeeper to use. The bottom of a conical skep was

left open so the keeper could turn it upside down and access the honey-

combs. A box hive had a hinged side or lid, and it often had removable

shelves for the bees to use. Pottery hives kept the bees cool during a hot

summer. The ends might be left open and then covered with a board until

the beekeeper wanted to access the hive.

Beekeeping was well developed in Italy by the early Middle Ages. Bee-

keepers used both horizontal box hives and conical wicker skeps, but, by

the 13th century, they began to favor boxes because they could be designed

for access from both front and back. If the bees’ entrance hole marked the

front, the back was where they stored their honey. But when they were rais-

ing new queens, these tended to be kept near the front. A keeper would

want to open the back for honey and the front to observe queen activity.

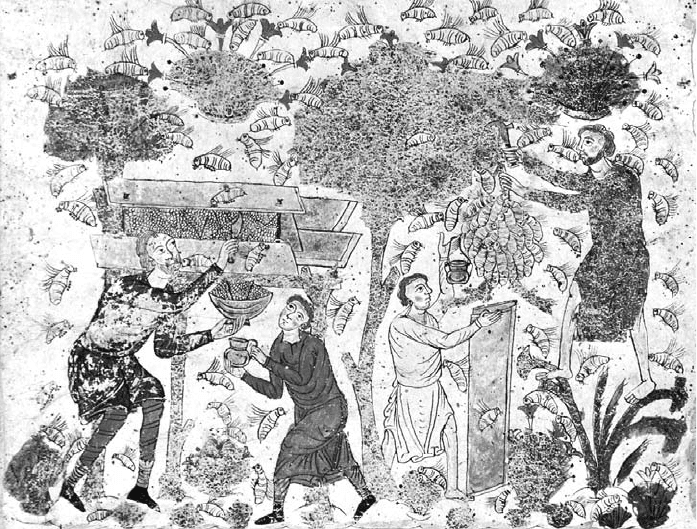

On the right, peasants capture wild bees in a tree; on the left, they remove honey

from combs in wooden boxes. (Vatican Library/The Bridgeman Art Library)

Beekeeping

55

Some keepers moved the growing queens so they could control when and

how the hive formed a new swarm.

In Northern Europe, bees needed help to survive eight months of ex-

tremely cold temperatures. Beekeepers in Sweden used different natural

materials, such as straw and bark, to insulate their hives very thickly in Sep-

tember, and those in warmer places that still had harsh winters did the same.

However, it was also common practice to harvest honey in the fall by killing

many of the bees that would have needed the honey as their winter food. A

good beekeeper was active collecting new swarms in early summer and then

identifi ed the less viable hives in the fall and smoked the bees to death. This

allowed him to harvest their honey while leaving full honeycombs for the

hives chosen to winter over. Insulated in their hives and with a full provision

of honey, these bees could survive anywhere except close to the Arctic Circle.

Bees in Finland, northern Sweden, and all but the southern tip of Norway

were not able to survive or become established in the environment.

In France, Denmark, the Netherlands, and England, the traditional bee-

hive was a conical skep made from wicker or straw that had been bound

into long ropes and then coiled and stitched into a cone. The interior of the

skep might include sticks to support layers of honeycomb. Honeycombs

could be cut, with a knife, from one side of the skep. But it was harder to

take honey from inside a coiled-straw skep as compared to a Mediterranean

box with a hinged lid. If the bees were not to be killed in the winter, the

other technique was to force the swarm to move into an empty hive in the

middle of the summer, leaving their honeycombs behind. Skeps were kept

small so bees could be easily divided this way.

In the heavily forested northeast of Europe—Germany and Poland—

some keepers either tended the bees inside their original tree, by placing a

door on the tree, or cut the section of trunk that included the hive and car-

ried it home. The section of trunk became the domestic hive. The trunks

were carved out for back access, with a bee hole in the front. Large trunks

could contain more than one compartment. In some regions, they were

placed vertically, and in others, horizontally. Honey removal was easier with a

horizontal trunk hive. In order to remove honey from a vertical trunk, the

keeper had to subdue the bees with smoke, though not enough to kill them.

In late medieval Poland, beekeepers began carving the trunks into deco-

rated shapes, such as women with large skirts. In these areas where bees

were traditionally kept in log hives, skeps made from coiled straw were a

later innovation, coming at the very end of the Middle Ages or later.

One of the problems inherent in beekeeping is that the bees do not stay

confi ned on their owner’s land, the way sheep do. While the owner may keep

the hive on his land, the bees will go far and wide, using the fl owers of oth-

ers. Medieval customs and regulations recognized the problems that went

with rights over beekeeping.

Beekeeping

56

In some places, peasants could keep bees that ranged across their lord’s

lands, but they had to pay a type of rent in honey or wax. Higher-class rent-

ers also paid rents to landowners with honey. A lord could expect to receive

a large amount of honey from his estates, as his many tenants turned over

honeycombs.

Most regions and towns regulated beekeeping in some way, recognizing

that bees not only had value to an owner, but also added value to the coun-

tryside by pollinating plants. A town might grant beekeeping rights over

adjoining wild lands to a man or a family on the condition that they give

half the honey to the town and maintain beekeeping on the land or sell it to

someone who could keep it up.

Sometimes, beekeepers stole swarms of bees from each other by luring a

swarm to nest on their land. Some kingdoms punished people who baited

empty skeps with fi nes of twice the value of the bee swarm they lured in. If

a man’s bees swarmed and moved into a neighbor’s land, and he followed

them, he could identify them as his swarm and either keep them there or

bring them home.

Bees might also injure people or animals. By the late Middle Ages, some

local laws required beekeepers to fence away their hive areas and to pay

heavy fi nes for animals that were stung to death if the fences were not strong

enough to keep the animals out. A person injured by bees could also receive

compensation from the owner, usually a measure of honey.

Most beekeeping was done on a small scale as part of other farming, but

there were also large beekeeping operations. Monasteries kept bees on a

large scale, and some farmers devoted themselves to beekeeping to the ex-

clusion of most other farming. Large-scale beekeeping meant upward of

100 hives, which would be a full-time job.

Beeswax was very important to churches because they used candles as

part of worship. Monasteries were some of the largest beekeepers, and, in

many parts of Europe, secular beekeepers were required to give some por-

tion of their wax to the local church. Churches were the biggest buyers

of wax; the value of wax rose when a region converted to Christianity and

fell following the post-medieval Reformation with its emphasis on simpler

worship without candles.

Both honey and wax had high values relative to their volume and weight,

so they were popular as bartering currency. Wax was also used for fees or

tributes in some places. Conquering peoples such as the Vikings and Tartars

accepted beeswax as part of their tribute.

Honey was commonly exported from the earliest medieval times, par-

ticularly to places where beekeeping was less common, as well as to towns.

By the era of the Hanseatic League, there were regulations for honey. Dis-

honest honey producers might mix fl our or other substances into the honey

to stretch it, sell it in a dirty condition, or pad the inside of the container

Beggars

57

so it did not hold as much as it appeared to. One reason for craft guilds

in honey or wax was to ensure the products that came from that region

were clean and pure. At the very end of the Middle Ages, beekeepers in the

Netherlands organized into a guild, as did some wax candle makers in

England.

See also: Agriculture, Food, Lights.

Further Reading

Alston, Frank, and Richard Alston. Skeps: Their History, Making, and Use. Hebden

Bridge, UK: Northern Bee Books, 1987.

Crane, Eva. The World History of Beekeeping and Honey Hunting. New York:

Routledge, 1999.

Kritsky, Gene. The Quest for the Perfect Hive: A History of Innovation in Bee Culture.

New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Beer. See Beverages

Beggars

A medieval city might have as many as a quarter of its people living in a

state of extreme poverty, including peasants who could not make a living

and those whose work was very marginal and paid too little to support

them. University students were often too poor to support their studies,

and some towns issued begging licenses to them and allowed them to re-

ceive alms.

The poorest people in medieval society were often sick or disabled.

These included cripples, lepers, the blind or deaf, and the mentally ill. Some

rented a privileged space next to the church door or were permitted to

build a small shelter by the church for a few pennies a year. They asked for

alms as people passed.

Leprosy was a disfi guring disease that began with red skin and a hoarse

voice. The skin became covered with sores and swellings until the person

was not recognizable. Nodular leprosy mostly attacked the face. Other

forms made fi ngers and feet rot and fall off. Leper skeletons show that

not only the skin but also the bones were disfi gured. It is possible that sev-

eral different diseases were all called leprosy, including syphilis.

Some lepers were cared for in colonies by monks, but others were per-

mitted to beg. They had to wear special clothing and ring a bell or rattle a

clapper. People could only give them things by stretching the items out on

poles to drop into the bowls lepers carried. Lepers were not permitted to

touch anyone’s skin. They had to walk in the gutter of the street and step

aside when anyone needed to pass.

Beggars

58

A leper woman, with a disfi gured face and amputated limbs, rings her warning

bell. (The British Library/StockphotoPro)

Wealthy people and monasteries gave alms to beggars, usually directly in

the form of food. Often, the household’s almoner, in charge of alms, col-

lected food scraps and used trenchers made of stale bread.

Towns began to register beggars and other extremely poor paupers and

gave them a limited amount of help. Each year, a pauper would receive a pair

of shoes, some clothing, and a set amount of basic foodstuffs like bread,

Bells

59

oil, and herring. The clothing a town’s paupers owned was usually in sol-

emn colors, since frequently the garments were bequests from wealthy citi-

zens for taking part in the prayers and processions for their funerals. The

prayers of paupers were considered more meritorious, so beggars were often

included in these processions and had to be dressed for the role. This cus-

tom made the offi cial poor stand out, since citizens who could buy their

own clothes preferred red, green, and blue.

In the 15th century, a new form of provision for some paupers came

about, based on the transition of hospitals to caring for the sick. Wealthy

donors built cottages, often under a single roof, like a modern townhouse.

They were called almshouses, and the donors specifi ed a particular purpose.

Some were for the widows of craftsmen who had belonged to a guild; some

were for paupers who shared the same surname as a donor. The pauper’s

appointment to a cottage came with a small stipend and a requirement to

pray for the donor’s soul. In many cases, the residents were required to wear

robes of a certain color, such as red or black.

See also: Cities, Funerals, Hospitals, Medicine.

Further Reading

Gies, Joseph, and Frances Gies. Life in a Medieval City. New York: Harper and

Row, 1969.

Hallet, Anna. Almshouses. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications, 2004.

Richards, Peter. The Medieval Leper. Cambridge, UK: D. S. Brewer, 1977.

Bells

Church bells and town bells were the most characteristic sounds of medi-

eval Europe, and, in some places, they were the only man-made noise ever

heard, apart from the pounding of hammers. Churches and monasteries

used bells to ring the hours of prayer and to call people to Mass. Bells rang

to announce a death, and a procession of mourners with handbells followed

the deceased to the grave. Certain holidays required more bell ringing; on

Easter, the bells rang at sunrise. Every town had a bell tower for calling out

summons and alarms. Bells rang when towns rose up in rebellion, and bel-

fries were torn down as a symbol of a rebellion’s being crushed.

Bells were made by brass founders, who became more specialized as bell-

founders as the centuries passed and more churches were built. They used the

same lost-wax technique they used to make brass basins and pots, but usually

on a much larger scale. Bell design was primitive during the Middle Ages,

since the physics of acoustics had not been developed. The basic design of a

bell was known, but nobody knew how to shape a bell to produce a certain

tone. Compared to modern bells, medieval bells were taller and thinner.