Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Armor

30

The mail maker worked with a dummy like a dressmaker’s. The dummy

had a head and shoulders, at least, so he could shape the fi t of the rings

around these surfaces. The mail across the chest and back did not need to

be carefully shaped, but a mail hood, and mail shoulders and arms, had to

fi t properly. Mail makers probably used written patterns that told them how

many rings to put in each row and how to link the rings for the proper

shape, but no patterns or guild treatises on the craft survived.

A mail hauberk alone was not enough. If the iron rings were pressed

hard against fl esh, they would cause their own injury, so there was always a

leather or padded tunic under the hauberk. Once cotton was imported from

Italy, it became the best quilt padding. During the 12th century, armor

makers invented mail mittens to protect a fi ghter’s fi ngers. Called muffl ers,

they had fabric on the palms and a slit the hand could slip through, allow-

ing the hand coverings to dangle. Armor makers also developed mail leg-

gings, called chausses, that attached to straps under the tunic. These, too,

had to be padded with leather or linen.

In Anglo-Saxon and Frankish times, it is unlikely that the common foot

soldier had a hauberk or byrnie. They were only used by elite warriors, as

described in Beowulf. By the end of the Carolingian period, before the Nor-

man conquest, 10th- and 11th-century soldiers were more likely to have

mail shirts. A hauberk was an expensive investment, and it was passed down

in families. In the 12th century, a lighter and less expensive form of mail

hauberk was called a haubergeon. It did not have long mail sleeves or mittens.

By the 13th century, there were even less expensive kinds of soft armor that

may not have used any chainmail, only quilted cotton padding. Quilted armor

types were called aketon (Arabic for cotton), gambeson, and pourpoint.

A 14th-century development from the chainmail hauberk was a sleeveless

leather tunic with metal plates riveted in an overlapping pattern that covered

the surface completely. It is often called a coat of plates. The plates them-

selves did a better job of guarding the wearer against arrow points, but the

riveted joints were weaker spots that an arrow or halberd might pierce. The

leather, too, could be hardened to provide some protection. The coat of

plates could be worn in combination with a mail hauberk, either over it

or under it. Similarly, there had been a Byzantine and Asian tradition to

use lamellar armor, which used small overlapping metal plates to cover the

surface of leather. Lamellar armor sometimes used hardened leather alone,

which was more common in areas that were both poorer and hotter than

Northern Europe.

The surcote was a linen tunic worn over chainmail. It kept the sun from

direct contact with the metal, which could heat to the point of burning its

wearer. The surcote was slit at the sides so it did not hinder movement.

Crusaders’ surcotes were decorated with a red cross. Other knights wore

surcotes with their heraldic arms or the arms of the lord they served.

Armor

31

Plate Armor

During the 13th century, metal plate armor began with open greaves

that covered the shins and knees worn under mail hauberks. Closed greaves

for the whole calf came after 1300, and then came full protection for the

upper leg, called a cuisse or cuish. The entire leg harness was called the

jamb, and its joint plate at the knee was called the poleyn. After 1380, leg

armor included the sabaton, an iron shoe made of narrow plates that moved

with the foot. Mounted on either steel shoe or leather boot, spurs com-

pleted the knight’s leg harness.

The fi rst plate armor for the body was a cuirass, a piece made to cover

the chest and back. After an original leather foundation provided its name,

the cuirass evolved into a shirt made of solid pieces of iron. Below the rib

cage, the armor needed to fl ex and bend with the body, so it was made as

iron rings riveted to a leather skirt on the main cuirass. These hoops could

overlap and move as the body moved. The skirt of hoops was called a fauld.

In the last years of the Middle Ages and moving into the Renaissance, ar-

morers added tassets, additional protective plates hanging from the fauld.

At the shoulders, where arm protection attached, there were hinged plates

called pauldrons.

Arm protection developed during the 14th century. Enclosed plates for

the forearm and upper arm, called cannons, were hinged and connected by

an elbow plate, the couter. The whole assembly was called a vambrace.

Pieces of armor might be hinged and buckled, or they could come in

separate pieces to be tied together. Some cuirasses were hinged on the left

and then buckled on the right; others were separate back and front pieces.

When armor was tied in place, it was often tied with laces sewn on the un-

dergarments. The laces were made of waxed twine and were called points.

Putting on armor took time and at least one servant ’s help.

Plate armor construction began with beating a sheet of heated iron

into a thin plate, often with a water mill that drove mechanical hammers.

Cut into proper shapes, the plates were beaten on anvils shaped like the

fi nal products. There were many different hammers, as well as different

forms, and the best armor was thicker and thinner in strategic places. At

some points, the metal could be hammered and worked while it was cold

enough to touch; some contemporary drawings show smiths holding the

pieces with bare hands. Frequently, the pieces had to be annealed; they

were reheated to red hot and then allowed to cool and worked while

still soft.

Fine shaping and fi tting had to be done with more care. Some knights

had wax models of their legs or arms made so the armor could be custom

fi tted for them; others had cloth patterns cut to their limbs so the armor

maker could reconstruct their exact shape. Fine adjustments in size and

curvature were then made, with the pieces frequently annealed. At this

Armor

32

stage, the edges of the plates were carefully fi tted together or curled around

to help defl ect blows.

Plates were case hardened by covering the outside with charcoal and heat-

ing it to red-hot again. The iron absorbed extra carbon and became a layer

of steel on the outside of the iron. If it cooled very fast by being plunged

into water, it became very hard and could be polished to look like glass,

but it was also more brittle. Slower cooling, or cooling and then reheat-

ing to temper it, produced the best result. The process of determining how

best to harden steel led to the fi rst industrial tests. Blades, arrows, or bul-

lets were used on the newly made armor to prove it was strong. This was

called “armor of proof,” and it was guaranteed to work. The full harness

was temporarily assembled, too, to check if it had been properly fi tted. It

was fi nished, but it was black, rough, and dented.

The pieces of plate armor were polished, either by hand or on a water-

driven polishing wheel. The steel began to shine like glass. For luxury

armor, the pieces were etched with acid or plated with gold. Finally, the

master armorer fi nished the harness. He riveted the pieces together and

riveted strips of leather to the proper edges. He riveted hinges made by a

locksmith and added more straps and buckles. Many of the plates were fi t-

ted with padding. The fi nal harness weighed around 60 pounds, compa-

rable to a modern soldier’s heavy pack.

In the 14th century, armorers developed plate armor for horses. The

most important plate, the peytral, covered the horse’s chest, which was

most vulnerable to a pike or lance attack. The face was also covered with a

plate that left the mouth and nose open and had eyeholes and ear covers.

This was called a shaffron, and a crinnet—a curved, hinged piece—sat on

the back of the horse’s neck. Usually the horse’s fl anks were covered with

leather to protect against scratches without inhibiting the horse’s move-

ment, but there were also full armor plates in occasional use. The crupper

was a set of curved plates for the horse’s back end, while the midsection was

protected by both the knight’s saddle and fl anchards. The horse’s armor

had to sit on a thickly quilted coat so it didn’t bruise the animal. There

must have been great danger for the horses to overheat.

See also: Crusades, Horses, Iron, Knights, Tournaments, Weapons.

Further Reading

Bouchard, Constance Brittain, ed. Knights in History and Legend. Buffalo, NY:

Firefl y Books, 2009.

Edge, David, and John Miles Paddock. Arms and Armor of the Medieval Knight: An

Illustrated History of Medieval Weaponry. New York: Crescent Books, 1993.

Fliegel, Stephen. Arms and Armor. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art,

2008.

Arthur, King

33

Nicolle, David. Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050–1350. 2 vols.

Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999.

Nicolle, David. Medieval Warfare Source Book: Warfare in Western Christendom.

London: Brockhampton Press, 1999.

Oakeshott, Ewart. The Archaeology of Weapons: Arms and Armour from Prehistory

to the Age of Chivalry. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1996.

Oakeshott, Ewart. A Knight and His Armor. Chester Springs, PA: Dufour Edi-

tions, 1999.

Pfaffenbichler, Matthias. Armourers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

Pollington, Stephen. The English Warrior: From Earliest Times till 1066. Hock-

wold, UK: Anglo-Saxon Books, 2002.

Williams, Alan. The Knight and the Blast Furnace: A History of the Metallurgy of

Armor in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Leiden, Netherlands:

Brill, 2003.

Arthur, King

Some of the legends we associate with the Middle Ages were already popu-

lar in their own time. In England, the legend of King Arthur was extremely

popular. The stories were anachronistic even then, set in a time long past

but dressed in the fashions and attitudes of the High Middle Ages. They

were a vehicle not only for entertainment but also for educating the aristoc-

racy in the values of courtly love and chivalry.

The setting for the legends of King Arthur is the period when the Roman

Empire was collapsing and the Germanic tribes were expanding across

Europe, pushing out the Celts who had been dominant under Rome. The

basic framework is that the Roman troops had left, and the Saxons had ini-

tial victories, but the Britons organized themselves and drove the Saxons out

for a time. During the time before the Anglo-Saxons returned in numbers,

Arthur, the king responsible for their military success, ruled his land in

peace and Christianity.

Scholars debate whether a real King Arthur existed. Arthurs are listed in

the Irish histories, but the details do not match the legends at all. At least

one Roman with the family name Artorius came to Britain. The history of

Gildas, a fi fth-century British monk, told about the Battle of Badon Hill in

which the Saxons were pushed back but did not mention Arthur. His mili-

tary leader is named Ambrosius Aurelianus, a name without clear similari-

ties to the name Arthur. Arthur could have been a nickname that came to

mask a very different historical given name. In 1985, Geoffrey Ashe argued

in The Discovery of Arthur that Camelot was Cadbury Castle in Somerset

and Riothamus, a Romanized British general, was the true Arthur.

After the Celtic Britons lost ground to the invading Anglo-Saxons, many

of them withdrew to the mountains of Wales or crossed the channel to

Arthur, King

34

France, founding the county of Brittany. King Arthur emerged from the

legends of Wales in the work of Geoffrey of Monmouth. Geoffrey, possibly

a native speaker of Breton, the Celtic language that survived in Brittany,

translated an earlier work into Latin, perhaps adding his own stories. His

book was called Historia Regum Britanniae: The History of the Kings of

Britain. In 1155, a Norman, Wace, translated Geoffrey’s work into French

poetry, the “Roman de Brut.” Wace added the Round Table and some

other fl ourishes.

Provençal troubadours took over the story from there, adding side

stories and new characters. The troubadours added the romance of Lance-

lot and Guinevere. Arthur’s story and related stories, such as Tristan and

Isolde, were called “Matter of Britain” by the troubadours. Between 1170

and 1190, Chrétien de Troyes, a troubadour at the court of Marie de France,

countess of Champagne, added the stories of “Yvain, Knight of the Lion,”

“Lancelot, Knight of the Cart,” and “Perceval, the Story of the Grail” to

the cycle. Around 1200, the English poet Layamon wrote the Arthurian

stories back into Middle English, adding more details; he made the Round

Table large enough to seat more than 1,000 knights. In the same period,

Robert de Boron wrote some poems in which Merlin created the Round

Table and made each name magically appear at a place. “Sir Gawain and the

Green Knight,” an anonymous poem in Middle English, was written in the

14th century.

Troubadours spread the stories, which were taken very seriously by both

royalty and commoners. The authenticity of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s

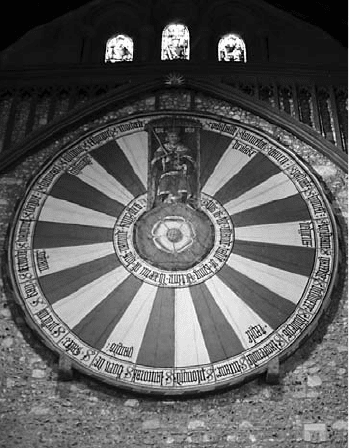

Winchester’s “Round Table,” made for

a feast, soon lost its true history; people

thought that it was King Arthur’s actual

table. (Nick Lewis Photography)

Arthur, King

35

history was not doubted, and the inventions of the early period were ab-

sorbed into the assumed truth of the whole. After 14-year-old Eleanor of

Provence married King Henry III in 1236, a court record suggests a trip to

see Arthur’s grave. Their son, King Edward I, ordered a large round table

made of wood and painted with the names of Arthur’s knights. It was used

at a feast in the Great Hall of Winchester Castle, probably for an Arthurian-

themed tournament. The table hung on the wall as a decoration for many

centuries, long after the castle had been dismantled. In 1485, William

Caxton, England’s fi rst printer, published Thomas Mallory’s collection of

Arthurian stories, Le Morte d’Arthur, translated from the French stories and

songs. Mallory probably arranged the existing stories and added more of

his own, playing up the Grail and including Arthur’s mystical death. A year

later, King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York named their fi rst son Arthur,

hoping to unite an England fractured by civil war behind the national sym-

bolism. Later, the large round table at Winchester Castle was even taken as

proof of Arthur’s existence.

The stories were set in a fabled 12-year peace between the Britons and

the Saxons, when Geoffrey’s history placed Arthur’s court at the center of

the world’s attention as a model of excellence. Arthur himself rarely starred

in the tales, but his court at Camelot served as the framework for a se-

ries of adventures for his knights. One of Arthur’s convenient traits was to

grant boons without knowing what they would be so plot complications

could arise. He usually insisted on an adventure before the court could

feast, which formed the frame story for stories like “Gawain and the Green

Knight.”

The basic types of Arthurian stories concerned the Holy Grail, Merlin,

Lancelot and Guinevere, and the death of Arthur. Family matters for the

knights were complicated; Arthur fathered a bastard son with his sister,

without knowing who she was, and Lancelot fathered Galahad with the

lady of the Grail Castle. Magical ladies, such as Morgan le Fay and the

Lady of the Lake, could enchant, distract, and deceive, as with the repeat-

ing character of the “false Guinevere.” Arthur’s death came about through

an involved story in which he must condemn his queen to death, besiege

Lancelot’s castle, and fi ght against his bastard son, Mordred. Magical ele-

ments were never far off, as when a hand comes out of the lake to receive

Excalibur at Arthur’s death. The cycle came to a rest with Merlin in an en-

chanted death-sleep, Arthur carried away by Morgan le Fay, Lancelot in a

monastery, and Guinevere in a convent.

The stories are profoundly anachronistic. Stone castles did not yet exist

in the 6th century; a real Camelot could not have been more than a timber-

walled hill fort. Although British, Irish, and Saxon kings had warrior bands,

they did not have knights in the 13th-century sense. In the 6th century,

warriors did not wear armor, nor did they hold tournaments. The British

Astrolabe

36

of the 6th century were Christians, but the cult of the Virgin Mary and

the Grail had not yet developed. Only the marriage details could be his-

torical, since kings always married the daughters or sisters of nearby or rival

kings. In the stories of Arthur, a medieval audience could enjoy a gilded

version of their own world, in which everyone had noble purposes and

experienced miracles.

The Arthurian cycle served a further purpose in medieval society.

Arthur’s knights were on the side of law and order, and they were deeply

religious. They fought against ghostly demon knights who had not been

true to the code of chivalry, and they opposed renegade knights who used

their strength to rob and oppress. Malory’s Arthurian tales state that each

year, the Round Table knights had to swear not to rape women. The legend

became a set of morality tales for the knights and their social class, remind-

ing them not to use their weapons for harm. In a heavily armed society, this

was a much-needed value.

See also: Castles, Knights, Minstrels and Troubadours, Tournaments.

Further Reading

Ashe, Geoffrey. The Discovery of King Arthur. New York: Anchor Press, 1985.

Biddle, Martin, ed. King Arthur’s Round Table. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press,

2000.

Chambers, E. K. Arthur of Britain. New York: October House, 1967.

Mallory, Thomas. Le Morte D’Arthur: The Winchester Manuscript. Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2008.

Monmouth, Geoffrey of. The History of the Kings of Britain. New York: Penguin

Books, 1977.

Troyes, Chrétien de. Arthurian Romances. New York: Penguin Classics, 2004.

Astrolabe

The astrolabe was an instrument used by astronomers, navigators, and

mathematicians. Its primary functions were to locate and predict the posi-

tions of the sun, moon, planets, and stars. It could be used for telling time

if the user’s latitude was known, for surveying, and for solving some ge-

ometry problems. A mariner’s astrolabe was developed for use on a ship ’s

deck. Similarly, the armillary sphere was a globe of the stars and planets

and could be used as a teaching aid, for navigation, and to calculate future

cycles of the planets.

The fi rst certain treatise on an astrolabe was written in 4th-century

Alexandria, a scientifi c center of the Roman and Byzantine cultures. Knowl-

edge of the astrolabe spread in Greek, Syriac, and Arabic, while travelers

Astrolabe

37

carried them to Persia and India and west to North Africa and Spain.

During the 10th century, scholars like Gerbert of Aurillac (the future Pope

Sylvester) learned the astrolabe’s use in Barcelona and translated treatises

into Latin. Most early European astrolabes were imported from Arabic re-

gions, but they were a standard part of university study by the 13th cen-

tury. They may not have been commercially produced in Europe until the

15th century.

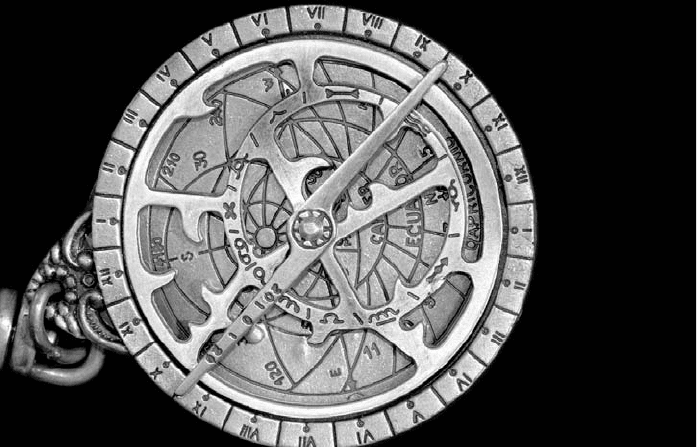

Astrolabes were made of brass. There was a hollow disk, the mater, that

was deep enough to hold fl at plates, the tympans. Each tympan was made

for a specifi c latitude and was engraved with lines to represent objects in

the sky as they appeared in that location. (Most astrolabes came with several

spare tympans for different altitudes; these nested inside the mater’s womb

and could be swapped when a traveler moved 70 miles north or south.) The

rim of the disk was marked with hours of time, usually on the front, with

degrees of arc on the back. On the back, there was often an alidade, a sight-

ing instrument that allowed the user to measure a star’s altitude. The front

had a rule, a rotating pointer. A single pin ran through the center, holding

all the turning pieces together.

The rete lay on top and could rotate. It was a precision-cut sheet of brass

that functioned like a star chart, with pointers to the brightest stars and cir-

cles, arcs, and lines showing the celestial equator, ecliptics, and tropics. The

center point functioned as the North Pole, while the rete itself was based

on the position of the stars at the South Pole. A single full rotation of the

rete represented one day.

Most astrolabes had charts etched into the quadrants of the back piece,

showing information needed for calculations. They could have a chart for

solving trigonometry problems, since the alidade could be used for land

surveying as well as astronomy. They could have data for calculating the

position of the sun, the direction of Mecca, or unequal hours.

The astrolabe’s chief purpose was to fi nd stars; an astronomer could pre-

dict times of a star’s rising without direct observation. In observation use,

the astrolabe could measure a star’s position so the astronomer could study

heavenly movement. An astronomer could measure distances in the sky,

such as a comet’s tail or the parallax of the moon. Astrology was considered

a branch of astronomical science, since it explained the “natural magic ” of

the stars. Astrologers could use the astrolabe to tell what stars were in con-

trol at the time of a baby’s birth or the right times to try bleeding.

The instrument also told time, and it showed how to convert between

the unequal hours used by common people and the exact equal hours of

science. Mosques used astrolabes to calculate the correct hours of prayer,

although Christian churches did not look for such precision in prayer hours.

Surveyors used astrolabes to solve trigonometric problems related to the

height of buildings or the distances between places they could not measure

Astrolabe

38

The astrolabe was the fi rst instrument to represent both time and space as a circle

divided into 24 units. (Brian Maudsley)

directly. Medieval surveyors could now measure the heights of mountains

and the distances between their peaks.

The principle of the astrolabe led to an early step in the development of

the clock. One early clock, made around 1330, was essentially a star map

rotating behind a fi xed rete. The idea of a rotating hand moving around a

marked dial led to the fi rst clock faces.

Armillary spheres were among the earliest complex mechanical devices.

The armillary sphere was built as a model of the universe. It consisted of a

set of graduated, interlocking brass rings (Latin armilla ) that represented

the circles made by the sun, the moon, the known planets, and some stars

as they seemingly revolved around the earth each day. Rings also showed

the equator, the earth’s poles, and the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn,

which mark the farthest points north and south at which the sun appears to

be directly overhead. The 12 signs of the zodiac also are marked on a ring.

At the center is a globe. During the Middle Ages, the armillary sphere was

geocentric—that is, the central globe was the earth, with the rings show-

ing how the sun, moon, stars, and so on all presumably revolved around

the earth.

Armillary spheres were developed by the Chinese and the Greeks. It

is not known with certainty which culture was the source of Europeans’

knowledge of the spheres. During the Middle Ages, however, armillary

Astrolabe

39

spheres became both more common and more sophisticated. There were

four main ways they were used.

Navigation was one important use of the armillary sphere. Sailors could

use it to determine both what time it was and what latitude their ship was

sailing on. It was used in astrology, to study the presumed connections be-

tween the heavens and events on earth. For example, people studied how

the stars and planets were aligned at the time of the plague, hoping the

next outbreak could be predicted; the medieval assumption was that cer-

tain alignments corrupted the air on earth. The armillary sphere was used

to teach astronomy in universities, since the rings could be moved to dem-

onstrate time and seasons. Similarly, church offi cials could use the sphere

to calculate the dates of Easter. Easter was supposed to be after the fi rst full

moon after the spring equinox.

See also: Clocks, Compass and Navigation, Maps, Ships and Boats.

Further Reading

Bork, Robert, and Andrea Kann, eds. The Art, Science, and Technology of Medieval

Travel. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2008.

Morrison, James E. The Astrolabe. London: Janus, 2007.

Stephenson, Bruce, Marvin Bolt, and Anna Friedman. The Universe Unveiled:

Instruments and Images through History. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2000.