Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

B

Babies

43

Babies

The two important events in a medieval baby’s life were live birth and bap-

tism. Infant mortality was high, and just surviving birth with a live mother

was a signifi cant achievement. Medieval people were sure babies who died

unbaptized could not go to heaven, so an infant in danger must be baptized

quickly. It is impossible to calculate infant mortality in medieval Europe be-

cause of inadequate record keeping, but as many as a quarter of babies may

have died in their fi rst year.

Babies were born at home with the help of a midwife and the mother’s

female relatives. Medieval society considered male doctors for women to

be a scandalous idea, and some women may have given birth alone rather

than let men assist them. When the baby was born, it was washed, some-

times in wine. In much of medieval Europe, babies were tightly swaddled

with their arms and legs held straight. It was believed that the infant’s limbs

needed to be straightened for the fi rst few months or their bones would

grow crooked.

Medieval baptism meant the offi cial naming of the child, as well as a cer-

emony that moved the child into Christendom—the kingdom of those who

had been christened, another term for baptism. Babies were baptized early

in their lives, often within a week, and not usually later than a few months.

Baptism took place in a church, and the baby was presented for baptism by

relatives or friends who stood in the place of the parents and made prom-

ises on the baby’s behalf for living a Christian life. The baby’s mother had

no offi cial role in the baptism because she was not permitted to come to

church for six weeks.

A baby boy required two godfathers and a godmother, while a baby girl

had two godmothers and a godfather. The godparents could not be rela-

tives of any close degree, and they could not be drawn from families the

baby might eventually marry into, since the church considered the godpar-

ent relationship as one that prohibited marriage. When the father was a

member of a craft guild, a fellow guild member often became a godfather.

Sometimes the lord of the manor stood as godfather.

The priest immersed the baby entirely in water three times while speak-

ing the ritual words in Latin, Et ego baptizo te in nomine patris, et fi lii, et

spiritus sancti. The priest drew a cross on the baby’s head with holy oil, and

the baby was wrapped in a hooded robe that covered this oil cross. God-

parents usually gave the infant a gift of money. Especially toward the later

Middle Ages, the priest recorded the christening in a parish records book.

Names went through a shift during the Middle Ages as people moved

from names in their native language to names from church tradition. The

Germanic tribes who spread over Europe at the close of the Roman period

used names like Edward, Frederick, Richard, Henry, Robert, William, and

Babies

44

Raymond or, for girls, Matilda, Emma, and Ethel. Names like these were

the most popular until Christian culture grew strong enough to infl uence

a shift to Bible names, saints ’ names, and names derived from Latin: John,

Matthew, Stephen, Peter, Paul, Benedict, and Bernard for boys or Joan,

Elizabeth, Mary, Katharine, Agnes, Margaret, and Clara for girls. Naming

traditions for babies varied across Europe, as they still do. Children were

named for parents, grandparents, and godparents, or they were named for

the saint on whose day they were born.

Swaddled babies were usually tied into cradles for much of their early

months. Some cradles hung on a wall, which kept the baby out of the way

of people and animals. Some cradles were on rockers that could be moved

with a foot. The richest mothers did not care for their own babies, but

hired wet nurses to breast-feed for them. Books about child care, aimed, of

course, at these wealthier families, emphasized care in selecting a wet nurse,

whose physical strength and character might be imparted to the baby.

In later medieval times, the range of baby equipment increased. Babies

had special clothing, dishes, and furniture. They wore shirts, caps, dresses,

A wealthy household’s servants tend to a woman in childbirth, the newborn baby’s

washing and warming, and the baby tucked into a cradle. (Paul Lacroix, Moeurs, Usage

et Costumes au Moyen Age et a l’Epoque de la Renaissance , 1878)

Banks

45

hose, and, of course, diapers that were probably wool or linen rags. Wash-

ing diapers was mostly a matter of boiling the rags, and the children of the

poor were probably not very clean. After they outgrew their cradles and be-

gan to walk, some babies had wooden frames with wheels, similar to mod-

ern walkers. Some people made padded baby bonnets as crash helmets for

beginning walkers. Babies had simple toys such as rattles. Since infancy was

thought to last until the age of seven, medieval people counted dolls and

marbles as babies’ toys.

Medieval rules of diet did not permit babies to have a wide range of

food. Doctors believed most foods would make babies sick, and they re-

ceived only the blandest food. Most babies lived on a diet of milk and bread

and possibly prechewed meat. One 13th-century book suggested peeled,

cored apple was a safe food for an infant and also recommended boiled

eggs, both soft and hard. At early ages, children began to drink ale, since it

was cleaner than water.

See also: Beverages, Church, Clothing, Food, Games.

Further Reading

Hanawalt, Barbara A. Growing Up in Medieval London: The Experience of Childhood

in History . New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Newman, Paul. Growing Up in the Middle Ages. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Pub-

lishers, 2007.

Orme, Nicholas. Medieval Children . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press,

2001.

Banks

Banks were slow to develop in the Middle Ages because the Catholic Church

declared it a sin to profi t on lending money. The reasoning was that a man

could lend money, but he could not charge for the time of the loan, since

time was a gift from God, and everyone had equal time. Time was not a com-

modity, according to the church. Yet if time itself could not be a commodity,

international commerce could not develop. During the Middle Ages, three

very different classes of people found ways around the problem.

The origin of modern banking lies in the need to exchange currency

while traveling and trading. Coins were regional and even local but were

based on the silver penny for most of the period. The standard set by Char-

lemagne became the standard for his Anglo-Saxon peers such as Offa, king

of Mercia. The basic equivalency of pennies and deniers and shillings and

solidi helped make trade across national lines easy. By the 13th century,

however, the wealthy cities of Italy were striking gold coins. Florence’s

gold coin was the fl orin, and Venice’s became known as the ducat.

Banks

46

These coins became new international money standards, especially since

the larger money unit of England and France, the pound, did not exist as

a coin, but only as a weight. Florins and ducats were currencies of much

higher value than pennies. Exchanging these currencies in trade meant

someone needed to keep on hand large sums of the local currency to ex-

change for foreign coins. Coins created another problem for the increas-

ingly large volume of international trade. Bringing enough cash to buy and

sell in another city meant carrying large chests of silver or gold that could

be stolen.

The fi rst international banking system was run by the Order of the

Knights of the Temple. This order of fi ghting monks, established in 1118,

aimed to keep the passage to the Holy Land safe for pilgrims, but many

wealthy people donated land and money to them, and they soon became

very rich. Individual members did not use the money for themselves, but

money piled up at Templar castles and became a private banking system.

Templar castles were safe repositories for treasure, and the monks were

sworn to poverty and honesty.

The Templars performed three basic banking functions. They guarded

and managed money for some lords and kings, made loans, and exchanged

currency for travelers. A merchant could give money to a Templar offi ce in

France and then travel to Jerusalem and receive his money in the local cur-

rency, without the danger of being robbed along the way. The Templars

charged an exchange fee for this service.

King Philip the Fair of France pressured Pope Clement to outlaw the

Templars in 1312, and he oversaw the trials of prominent Templars who

were accused of exotic practices and crimes. Temple lands and money went

to the Order of the Hospitalers, and some to King Philip. The private bank-

ing system of the Knights of the Temple disbanded.

International merchants had been carrying out the same banking func-

tions among their own branches, and, during the 13th century, they began

to offer these services to others. Like the Templars, branches of Italian ship-

ping companies had cash on hand and could issue letters of credit for a

traveler that could be cashed at another branch offi ce. Jewish merchants

operated a similar network among themselves. Their services began to in-

clude short-term loans that covered the purchase of goods and could be re-

paid in another city when the goods had been sold.

The concept of lending as “the sin of usury” originated in agriculture.

When poor farmers borrowed until the next harvest cycle, high rates of in-

terest contributed to drive them further into poverty. The church ruled

that this was a sin among Christians. International trade, however, de-

pended on lending not as a means to drive people into greater poverty, but

as a way to purchase shiploads of merchandise like spices and sell them at

a profi t. These borrowers could afford to pay for time as a commodity so

Banks

47

that both trader and lender profi ted. They had to fi nd a way around the

church’s rule.

Letters of credit and bills of exchange solved the problems of carrying

coins and fi nding loans. Letters of credit, sold by merchant bankers to trav-

elers, could be redeemed for coin at another city’s offi ce of the same mer-

chant bankers. As merchants in a city began to keep money deposited for

safekeeping with one merchant banker, they could also request payments

to other merchants; these payments were deducted from their credit ac-

count so that no money changed hands directly. The merchant banker

could subtract a fee for the service of the letter of credit.

Currency exchange was another method of dodging the rules against

usury. When changing silver deniers to gold fl orins, a banker had to make

judgments as to how many deniers a fl orin was worth. Within this judg-

ment call, there was room to disguise a fee. When the currency was bor-

rowed in deniers and repaid six months later in fl orins, the banker could

pocket an interest on the loan without appearing to be a usurer.

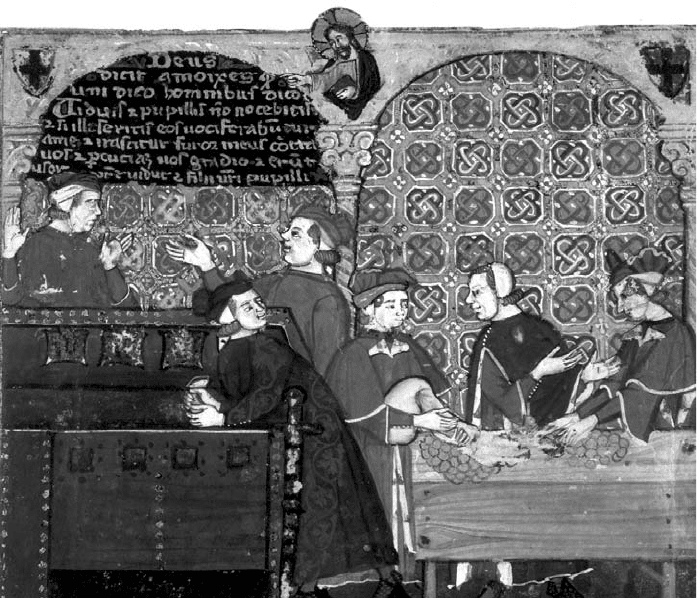

The word counter for a wide table or shelf in a store comes from the use of such tables

to count coins in medieval counting houses. (The British Library/StockphotoPro)

Banks

48

Some Jewish merchants had already been acting as bankers not only to

merchants but also to kings. Church law did not apply to them, and civil law

did not forbid interest on loans. Jews did not charge interest to each other,

but they did lend at interest to Christians. They became known as sinful

usurers, but they were tolerated and encouraged by kings who could bor-

row from them in preparation for war. Jewish bankers were often unwill-

ing participants in these loans. While cloth merchants would repay a loan,

kings often did not. In England and France, Jews were at times stripped of

their possessions and evicted partly so the kings did not have to repay on

loans. Even when the law merely regulated Jewish lending without dispos-

sessing them, there was often discrimination. An early 13th-century French

law specifi ed that Jews could not charge more than a few pennies per pound

of loan. Discrimination was part of medieval life.

The Italian merchant bankers developed banking almost to a modern

level of complexity. Political instability in 13th-century Italy had encour-

aged merchants to develop structures that permitted them to trade in other

regions without leaving home. The cloth manufacturing of northern Italy

grew to be organized in family-controlled companies with branches in

more than one city. Instead of one individual making investments, con-

tracting debts, and overseeing operations through paid agents, these com-

panies were composed of members who shouldered the tasks together. At

fi rst they were relatives within a family but came to include outsiders who

could invest money as shareholders.

The Italian companies were represented at the large fairs of Northern

Europe, such as Champagne, Frankfort, and Cambridge. They worked

with letters of credit and currency exchange at the fairs. Some deals were

paid for in credit at the fairs. The Keeper of the Fair would notarize a

“Letter of the Fair” that stated the terms of the exchange with a prom-

ise for future payment. This notarized letter could be used as further cur-

rency for another deal, sold as payment to a third party. Interest rates were

fi xed by law, even when they were for currency-exchange services. At the

Champagne fairs, no more than 15 percent could be charged as a currency-

exchange fee.

The 14th century, fi lled with famine and plague, put an end to the

large, profi table Italian companies. Most were bankrupt by 1400. In the

15th century, there was a movement in Italy to create an institution to

cushion individuals from the instant poverty of sudden inability to pay a

debt. This was called the monte di pieta and was promoted by a Franciscan

friar. He wanted the wealthy to donate to this fund to lend money to those

who needed small loans for businesses. Town governments also devoted

some tax money to the montes when they established them. Borrowers

left valuable objects as pledges when they used these community lending

services.

Banks

49

Accounting Methods

Tally sticks were the earliest type of loan accounting. A stick that could

be split was carefully notched to show the sum being borrowed by a mer-

chant or a government. The notches were wide enough to go well across

the stick; the stick was split down the middle so both halves showed the

marks of the notches. The lender kept the larger piece, called the stock, and

the borrower kept the shorter piece.

Another way of counting sums, a sort of manual cash register, was the

counting-board, called the exchequer. It was a wooden platter with a rim

around it, covered with linen and chalked off into a chessboard pattern.

Coins, or coin stand-ins called jetons, could be added in columns. On a

French counting-board at a large Champagne fair, there was a column for

the smallest unit of money, the heller. The next column stood for sous, and

then pounds, 20 pounds, 100 pounds, and 1,000 pounds.

During the 13th and 14th centuries, Italian companies developed new

methods of accounting. Merchants had always kept track of money received

or paid. The original, primitive method of making notches or marks on a

stick had given way to paper books, but the entries were written in a sin-

gle column. Although an accountant could use the record to calculate the

business’s value at any time, it was diffi cult to sort the types of entries. By en-

tering debits and credits in separate columns, an accountant could keep a

running sum of the business’s capital on hand and its value in purchased

supplies. At fi rst, these entries were kept on facing pages—a system devel-

oped in Venice. Gradually, the entries were kept on the same page using a

double column, the way simple accounting is done today.

During the 14th century, accountants converted to the Arabic numeral

system used in modern times. Some Italian merchants had converted to

Arabic accounting as early as the 12th century because they had warehouses

in North Africa. Leonardo of Pisa, known as Fibonacci, learned account-

ing with Arabic numerals in the late 12th century by working at the family’s

warehouse in Bougia, North Africa. However, Italian city governments were

afraid the new numbers were easier to doctor in account books, and they

outlawed them around 1300. By 1400, many accountants were using them

anyway, and by 1500, they were universally adopted.

See also: Coins, Fairs, Gold and Silver, Jews, Numbers.

Further Reading

Frugoni, Chiara. Books, Banks, Buttons, and Other Inventions from the Middle Ages.

New York: Columbia University Press, 2003

Hunt, Edwin S., and James M. Murray. A History of Business in Medieval Europe,

1299–1550. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Lopez, Robert S. The Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages, 950–1350. Cam-

bridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.