Jacobson M.Z. Atmospheric Pollution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

respiration and organic matter decomposition cause the partial pressure of CO

2

(g) to

be about 10 to 100 times that in the atmosphere (Brook et al., 1983). Thus, calcite is

broken down and CO

2

(g) is removed more readily within soils than at soil surfaces.

Dissolved calcium ultimately flows with runoff back to the oceans, where some of it is

stored and the rest of it is converted to shell material.

Mixing Ratios

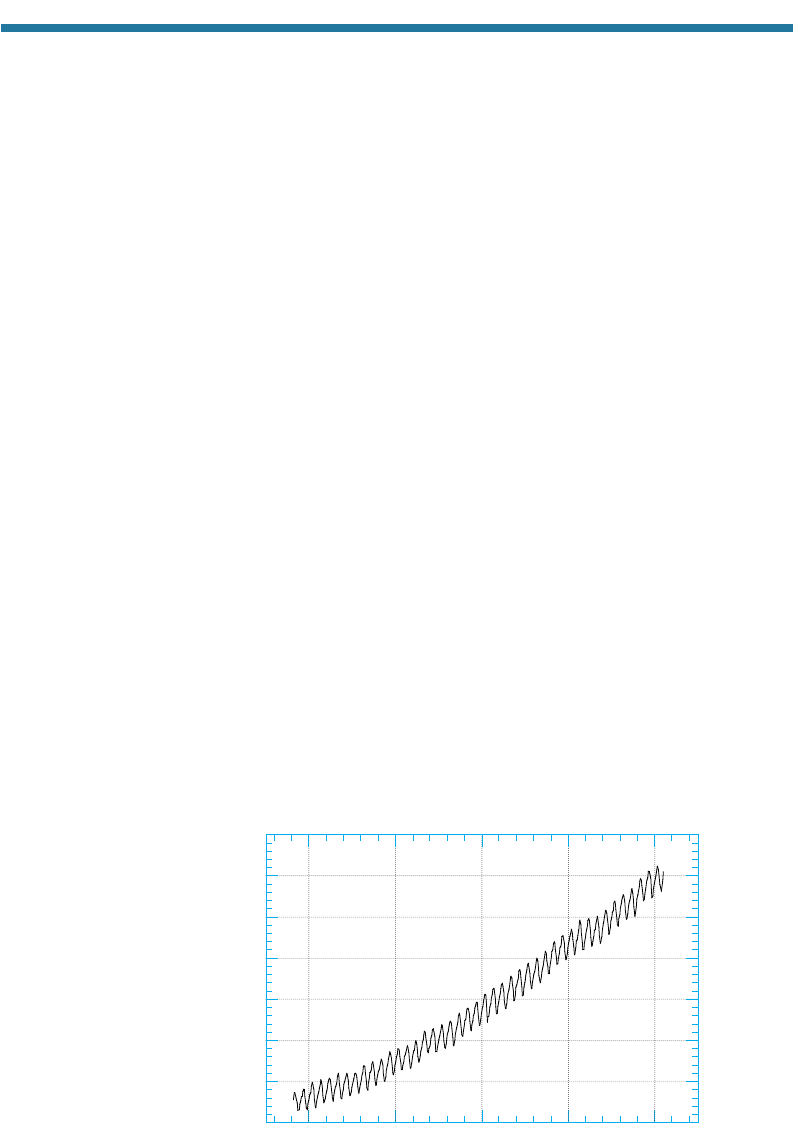

Figure 3.11 shows how outdoor CO

2

(g) mixing ratios have increased steadily since

1958 at the Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii. Average global CO

2

(g) mixing ratios

have increased from approximately 280 ppmv in the mid-1800s to approximately 370

ppmv today. The yearly increases are due to increased CO

2

(g) emission from fossil-

fuel combustion. The seasonal fluctuation in CO

2

(g) mixing ratios is due to

photosynthesis and bacterial decomposition. When annual plants grow in the spring

and summer, photosynthesis removes CO

2

(g) from the air. When such plants die in the

fall and winter, their decomposition by bacteria adds CO

2

(g) to the air. Typical indoor

mixing ratios of CO

2

(g) are 700 to 2,000 ppmv, but can exceed 3,000 ppmv when

unvented appliances are used (Arashidani et al., 1996).

Health Effects

Outdoor mixing ratios of CO

2

(g) are too low to cause noticeable health problems.

In indoor air, CO

2

(g) mixing ratios may build up enough to cause some discomfort, but

those higher than 15,000 ppmv are necessary to af

fect human respiration. Mixing

ratios higher than 30,000 ppmv are necessary to cause headaches, dizziness, or nausea

(Schwarzberg, 1993). Such mixing ratios do not generally occur.

3.6.3. Carbon Monoxide

Carbon monoxide [CO(g)] is a tasteless, colorless, and odorless gas. Although CO(g)

is the most abundantly emitted variable gas aside from CO

2

(g) and H

2

O(g), it plays a

small role in ozone formation in urban areas. In the background troposphere, it plays a

68 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

310

320

330

340

350

360

370

380

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

CO

2

(g) mixing ratio (ppmv)

Year

Figure 3.11. Yearly and seasonal fluctuations in carbon dioxide mixing ratio at Mauna Loa

Observatory, Hawaii, since 1958. Data for 1958–1999 from Keeling and Whorf (2000) and

for 2000 from Mauna Loa Data Center (2001).

larger role in ozone formation. CO(g) is not a greenhouse gas, but its emission and

oxidation to CO

2

(g) affect global climate. CO(g) is not important with respect to

stratospheric ozone reduction or acid deposition. CO(g) is an important component of

urban and indoor air pollution because it has harmful short-term health effects. CO(g)

is one of six pollutants, called criteria air pollutants (Section 8.1.5), for which U.S.

National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) were set by the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) under the 1970 U.S. Clean Air Act

Amendments (CAAA70). CO(g) is now regulated in man

y other countries as well

(Section 8.2).

Sources and Sinks

Table 3.8 summarizes the sources and sinks of CO(g). A major source of CO(g) is

incomplete combustion in automobiles, trucks, and airplanes. CO(g) emission sources

include wildfires, biomass burning, nontransportation combustion, some industrial

processes, and biological activity. Indoor sources of CO(g) include water heaters, coal

and gas heaters, and gas stoves. The major sink of CO(g) is chemical conversion to

CO

2

(g). It is also lost by deposition to soils and ice caps and dissolution in ocean

water. Because it is relatively insoluble, its dissolution rate is slow.

Table 3.9 shows that, in 1997, total emissions of CO(g) in the United States were

90 million short tons (1 metric ton 1.1023 short tons). The largest source was trans-

portation. CO(g) emissions decreased in the United States between 1988 and 1997 by

about 25 percent, primarily due to the increased use of the catalytic converter in vehi-

cles (Chapter 8).

Mixing Ratios

Mixing ratios of CO(g) in urban air are typically 2 to 10 ppmv. On freeways and in

traffic tunnels, they can rise to more than 100 ppmv. Typical CO(g) mixing ratios

inside automobiles in urban areas range from 9 to 56 ppmv (Finlayson-Pitts and Pitts,

1999). In indoor air, hourly average mixing ratios can reach 6–12 ppmv when a gas

stove is turned on (Samet et al., 1987). In the absence of indoor sources, CO(g) indoor

mixing ratios are usually less than are those outdoors (Jones, 1999). In the free tropo-

sphere, CO(g) mixing ratios vary from 50 to 150 ppbv.

Health Effects

Exposure to 300 ppmv of CO(g) for one hour causes headaches; exposure to 700

ppmv of CO(g) for one hour causes death, CO(g) poisoning occurs when it dissolves

in blood and replaces oxygen as an attachment to hemoglobin [Hb(aq)], an iron-con-

taining compound. The conversion of O

2

Hb(aq) to COHb(aq) (carboxyhemoglobin)

causes suffocation. CO(g) can also interfere with O

2

(g) diffusion in cellular mitochon-

dria and with intracellular oxidation (Gold, 1992). For the most part, the effects of

CO(g) are reversible once exposure to CO(g) is reduced. Following acute exposure,

STRUCTURE AND COMPOSITION OF THE PRESENT-DAY ATMOSPHERE 69

Table 3.8. Sources and Sinks of Atmospheric Carbon Monoxide

Fossil-fuel combustion Kinetic reaction to carbon dioxide

Biomass burning Transfer to soils and ice caps

Photolysis and kinetic reaction Dissolution in ocean water

Plants and biological activity in oceans

Sources Sinks

however, individuals may still express neurologic or psychologic symptoms for weeks

or months, especially if they become unconscious temporarily (Choi, 1983).

3.6.4. Methane

Methane [CH

4

(g)] is the most reduced form of carbon in the air. It is also the simplest

and most abundant hydrocarbon and organic gas. Methane is a greenhouse gas that

absorbs thermal-IR radiation 25 times more efficiently, molecule for molecule, than does

CO

2

(g), but mixing ratios of carbon dioxide, are much larger than are those of methane.

Methane slightly enhances ozone formation in photochemical smog, but because the

incremental ozone produced from methane is small in comparison with ozone produced

from other hydrocarbons, methane is a relatively unimportant component of photochem-

ical smog. In the stratosphere, methane has little effect on the ozone layer, but its

chemical decomposition provides one of the few sources of stratospheric water vapor.

Neither the emission nor ambient concentration of methane is regulated in any country.

Sources and Sinks

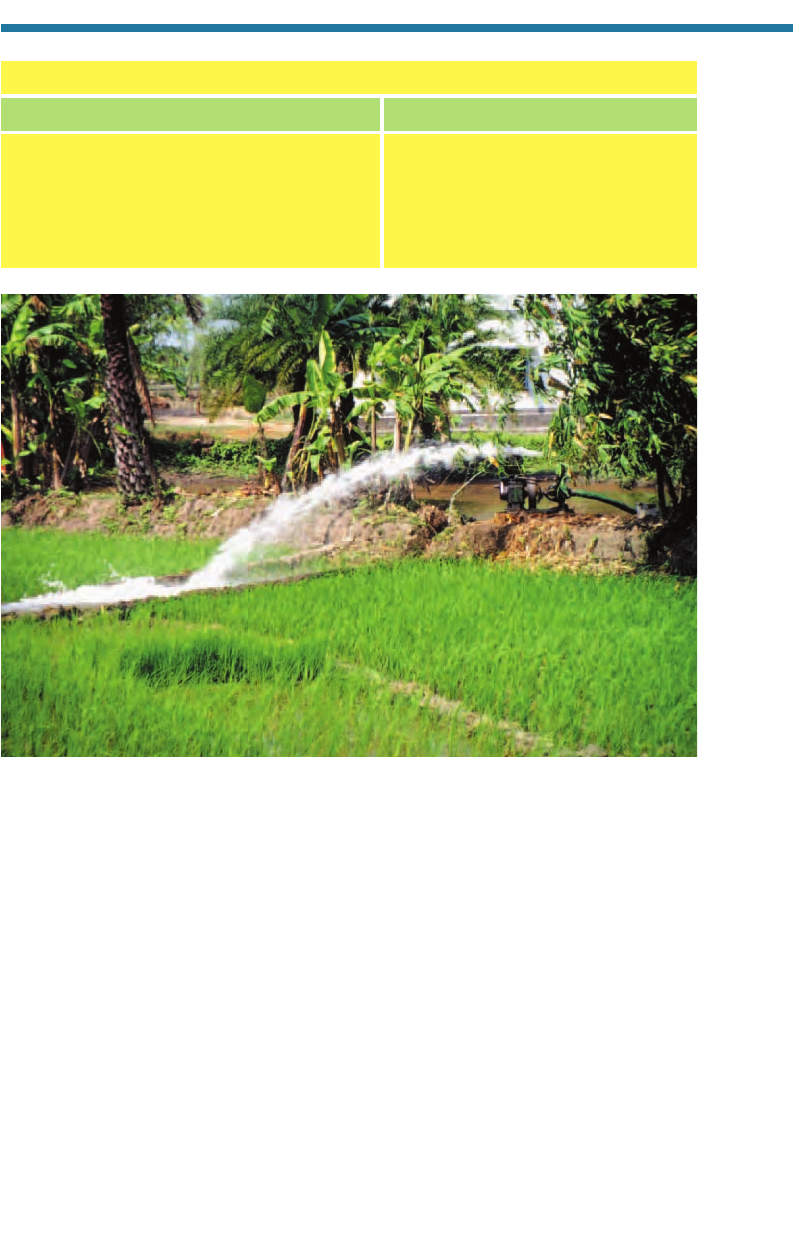

Table 3.10 summarizes the sources and sinks of methane. Methane is produced in

anaerobic environments, where methanogenic bacteria consume organic material and

excrete methane (Equation 2.4). Ripe anaerobic environments include rice paddies

(Fig. 3.12), landfills, wetlands, and the digestive tracts of cattle, sheep, and termites.

Methane is also produced in the ground from the decomposition of fossilized carbon.

The resulting natural gas, which contains more than 90 percent methane, often

leaks to the air or is harnessed and used for energy. Methane is also produced during

70 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

Table 3.9. Estimated Total Emissions and P

ercentage of T

otal Emissions b

y Source Categor

y

in the United States in 1997

Carbon CO(g) 90 6.9 5.5 76.6 11.0

monoxide

Nitrogen NO

(g) 24 3.9 45.4 49.2 1.5

oxides

Sulfur SO

2

(g) 20 8.4 84.7 6.6 0.3

dioxide

Particulate PM

10

(aq,s) 37 3.9 3.2 2.2 90.7

matter

10 m

a

Lead Pb(s) 0.004 74.1 12.6 13.3 0

Reactive ROGs 20 51.2 4.5 39.9 4.4

organic

gases

Industrial Fuel Transportation

Processes Combustion (mobile

Chemical Total Emissions (area sources; (point sources; sources; Miscellaneous

Formula (10

6

short tons percentage percentage percentage (percentage

Substance or Acronym per year) of total) of total) of total) of total)

a

PM

10

is particulate matter with diameter 10 m. Miscellaneous PM

10

sources include fugitive dust (57.9

percent of total PM

10

emissions), agricultural and forest emissions (14.0 percent), wind erosion (15.8 percent),

and other combustion sources (3.0 percent).

Source: U.S. EPA (1997).

biomass burning, fossil-fuel combustion, and atmospheric chemical reactions. Its sinks

include chemical reactions, transfer to soils, ice caps, the oceans, and consumption by

methanotrophic bacteria. The e-folding lifetime of methane due to chemical reaction is

about 8 to 12 years, which is slow in comparison with the lifetimes of other organic

gases. Because methane is relatively insoluble, its dissolution rate into ocean water is

slow. Approximately 80 percent of the methane in the air today is biogenic in origin;

the rest originates from fuel combustion and natural gas leaks

Mixing Ratios

Methane’s average mixing ratio in the troposphere is near 1.8 ppmv, which is an

increase from about 0.8 ppmv in the mid-1800s (Ethridge et al., 1992). Its tropospheric

mixing ratio has increased steadily due to increased biomass burning, fossil-fuel com-

bustion, fertilizer use, and landfill development. Mixing ratios of methane are relatively

constant with height in the troposphere, but decrease in the stratosphere due to chemical

loss. At 25 km, methane’s mixing ratio is about half that in the troposphere.

STRUCTURE AND COMPOSITION OF THE PRESENT-DAY ATMOSPHERE 71

Table 3.10. Sources and Sinks of Atmospheric Methane

Methanogenic bacteria (lithotrophic autotrophs) Kinetic reaction

Natural gas leaks during fossil-fuel mining Transfer to soils and ice caps

and transport Methanotrophic bacteria (conventional

Biomass burning heterotrophs)

Fossil-fuel combustion

Kinetic reaction

Sources Sinks

Figure 3.12. Rice paddies, such as this one in Sundarbans, West Bengal, India, produce not

only an important source of food, but also methane gas. Photo by Jim Welch, available from

the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Health Effects

Methane has no harmful human health effects at typical outdoor or indoor mixing

ratios.

3.6.5. Ozone

Ozone [O

3

(g)] is a relatively colorless gas at typical mixing ratios. It appears faintly

purple when its mixing ratios are high because it weakly absorbs green wavelengths of

visible light and transmits red and blue, which combine to form purple. Ozone exhibits

an odor when its mixing ratios exceed 0.02 ppmv. In urban smog or indoors, it is con-

sidered an air pollutant because of the harm that it does to humans, animals, plants,

and materials. In the United States, it is one of the six criteria air pollutants that

requires control under CAAA70. It is also regulated in many other countries. In the

stratosphere, ozone’s absorption of UV radiation provides a protective shield for life

on Earth. Although ozone is considered to be “good” in the stratosphere and “bad” in

the boundary layer, ozone molecules are the same in both cases.

Sources and Sinks

Table 3.11 summarizes the sources and sinks of ozone. Ozone is not emitted. Its

only source into the air is chemical reaction. Sinks of ozone include reaction,

transfer

to soils and ice caps, and dissolution in ocean waters. Because ozone is relatively

insoluble, its dissolution rate is relatively slow.

Mixing Ratios

In the free troposphere, ozone mixing ratios are 20 to 40 ppbv near sea level and

30 to 70 ppbv at higher altitudes. In urban air, ozone mixing ratios range from less

than 0.01 ppmv at night to 0.50 ppmv (during afternoons in the most polluted cities

world wide), with typical values of 0.15 ppmv during moderately polluted afternoons.

Indoor ozone mixing ratios are almost always less than are those outdoors. In the strat-

osphere, peak ozone mixing ratios are around 10 ppmv.

Health Effects

Ozone causes headaches at mixing ratios greater than 0.15 ppmv, chest pains at

mixing ratios greater than 0.25 ppmv, and sore throat and cough at mixing ratios greater

than 0.30 ppmv. Ozone decreases lung function for people who exercise steadily for

more than an hour while exposed to concentrations greater than 0.30 ppmv. Symptoms

of respiratory problems include coughing and breathing discomfort. Small decreases

in lung function affect people with asthma, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema. Ozone

may also accelerate the aging of lung tissue. At levels greater than 0.1 ppmv, ozone

affects animals by increasing their susceptibility to bacterial infection. It also interferes

with the growth of plants and trees and deteriorates organic materials, such as rubber,

72 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

Table 3.11. Sources and Sinks of Atmospheric Ozone

Chemical reaction of O(g) with O

2

(g) Photolysis

Kinetic reaction

Transfer to soils and ice caps

Dissolution in ocean water

Sources Sinks

textile dyes and fibers, and some paints and coatings (U.S. EPA, 1978). Ozone increases

plant and tree stress and their susceptibility to disease, infestation, and death.

3.6.6. Sulfur Dioxide

Sulfur dioxide [SO

2

(g)] is a colorless gas that exhibits a taste at levels greater than

0.3 ppmv and a strong odor at le

vels greater than 0.5 ppmv. SO

2

(g) is a precursor to

sulfuric acid [H

2

SO

4

(aq)], an aerosol particle component that affects acid deposition,

global climate, and the global ozone layer. SO

2

(g) is one of the six air pollutants

for which NAAQS standards are set by the U.S. EPA under CAAA70. SO

2

(g) is now

regulated in many countries.

Sources and Sinks

Table 3.12 summarizes the major sources and sinks of SO

2

(g). Some sources include

coal-fired power plants, automobile tailpipes, and volcanos. SO

2

(g) is also produced

chemically in the air from biologically produced dimethylsulfide [DMS(g)] and hydro-

gen sulfide [H

2

S(g)]. SO

2

(g) is removed by chemical reaction,

dissolution in water, and

transfer to soils and ice caps. SO

2

(g) is relatively soluble. SO

2

(g) emissions decreased

in the U.S. between 1988 and 1997 by about 12 percent. Table 3.9 shows that, in 1997,

the total mass of emitted SO

2

(g) in the United States was 20 million short tons. Between

1988 and 1997, SO

2

(g) emissions decreased in the United States by 17 percent.

Mixing Ratios

In the background troposphere, SO

2

(g) mixing ratios range from 10 pptv to 1 ppbv.

In polluted air, they range from 1 to 30 ppbv. SO

2

(g) levels are usually lower indoors

than outdoors. The indoor to outdoor ratio of SO

2

(g) is typically between 0.1:1 to 0.6:1

in buildings without indoor sources (Jones, 1999). In one study, indoor mixing ratios

were found to be 30 to 57 ppbv in homes equipped with kerosene heaters or gas stoves

(Leaderer et al., 1984, 1993).

Health Effects

Because SO

2

(g) is soluble, it is absorbed in the mucous membranes of the nose and

respiratory tract. Sulfuric acid [H

2

SO

4

(aq)] is also soluble, but its deposition rate into

the respiratory tract depends on the size of the particle in which it dissolves (Maroni et

al., 1995). High concentrations of SO

2

(g) and H

2

SO

4

(aq) can harm the lungs (Islam and

Ulmer, 1979). Bronchiolar constrictions and respiratory infections can occur at mixing

ratios greater than 1.5 ppmv. Long-term exposure to SO

2

(g) from coal burning is asso-

ciated with impaired lung function and other respiratory ailments (Qin et al., 1993).

People exposed to open coal fires emitting SO

2

(g) are likely to suffer from breathlessness

and wheezing more than are those not exposed to such fires (Burr et al., 1981).

STRUCTURE AND COMPOSITION OF THE PRESENT-DAY ATMOSPHERE 73

Table 3.12. Sources and Sinks of Atmospheric Sulfur Dioxide

Oxidation of DMS(g) Kinetic reaction to H

2

SO

4

(g)

Volcanic emission Dissolution in cloud drops and ocean water

Fossil-fuel combustion Transfer to soils and ice caps

Mineral ore processing

Chemical manufacturing

Sources Sinks

3.6.7. Nitric Oxide

Nitric oxide [NO(g)] is a colorless gas and a free radical. It is important because it is a

precursor to tropospheric ozone, nitric acid [HNO

3

(g)], and particulate nitrate [NO

3

].

Whereas NO(g) does not directly affect acid deposition, nitric acid does. Whereas

NO(g) does not affect climate, ozone and particulate nitrate do. Natural NO(g) reduces

ozone in the upper stratosphere. Emissions of NO(g) from jets that fly in the strato-

sphere also reduce stratospheric ozone. Outdoor levels of NO(g) are not regulated in

any country.

Sources and Sinks

Table 3.13 summarizes the sources and sinks of NO(g). NO(g) is emitted by

microbes in soils and plants during denitrification, and it is produced by lightning,

combustion,

and chemical reaction. Combustion sources include aircraft, automobiles,

oil refineries, and biomass burning. The primary sink of NO(g) is chemical reaction.

Mixing Ratios

A typical sea-level mixing ratio of NO(g) in the background troposphere is 5 pptv.

In the upper troposphere, NO(g) mixing ratios are 20 to 60 pptv. In urban regions,

NO(g) mixing ratios reach 0.1 ppmv in the early morning,

but may decrease to zero by

midmorning due to reaction with ozone.

Health Effects

Nitric oxide has no harmful human health effects at typical outdoor or indoor mix-

ing ratios.

3.6.8. Nitrogen Dioxide

Nitrogen dioxide [NO

2

(g)] is a brown gas with a strong odor. It absorbs short (blue

and green) wavelengths of visible radiation, transmitting the remaining green and all

red wavelengths, causing NO

2

(g) to appear brown. NO

2

(g) is an intermediary between

NO(g) emission and O

3

(g) formation. It is also a precursor to nitric acid, a component

of acid deposition. Natural NO

2

(g), like natural NO(g), reduces ozone in the upper

stratosphere. NO

2

(g) is one of the six criteria air pollutants for which ambient stan-

dards are set by the U.S. EP

A under CAAA70. It is now regulated in many countries.

Sources and Sinks

Table 3.14 summarizes sources and sinks of NO

2

(g). Its major source is oxidation

of NO(g). Minor sources are fossil fuel combustion and biomass burning. During

74 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

Table 3.13. Sources and Sinks of Atmospheric Nitric Oxide

Denitrification in soils and plants Kinetic reaction

Lightning Dissolution in ocean water

Fossil-fuel combustion Transfer to soils and ice caps

Biomass burning

Photolysis and kinetic reaction

Sources Sinks

combustion or burning, NO

2

(g) emissions are about 5 to 15 percent those of NO(g).

Indoor sources of NO

2

(g) include gas appliances, kerosene heaters, woodburning

stoves, and cigarettes. Sinks of NO

2

(g) include photolysis, chemical reaction, dissolu-

tion into ocean water, and transfer to soils and ice caps. NO

2

(g) is relatively insoluble

in water. Table 3.9 shows that in 1997,

24 million short tons of NO

2

(g) were emitted in

the United States.

Mixing Ratios

Mixing ratios of NO

2

(g) near sea level in the free troposphere range from 20 to

50 pptv. In the upper troposphere, mixing ratios are 30 to 70 pptv. In urban regions,

they range from 0.1 to 0.25 ppmv. Outdoors, NO

2

(g) is more prevalent during mid-

morning than during midday or afternoon because sunlight breaks down most

NO

2

(g) past midmorning. In homes with gas-cooking stoves or unvented gas space

heaters, weekly average NO

2

(g) mixing ratios can range from 21 to 50 ppbv,

although peak mixing ratios may reach 400–1,000 ppbv (Spengler, 1993; Jones

et al., 1999).

Health Effects

Although exposure to high mixing ratios of NO

2

(g) harms the lungs and increases

respiratory infections (Frampton et al., 1991), epidemiologic evidence indicates that

exposure to typical mixing ratios of NO

2

(g) has little effect on the general population.

Children and asthmatics are more susceptible to illness associated with high NO

2

mix-

ing ratios than are adults (Li et al., 1994). Pilotto et al. (1997) found that levels of

NO

2

(g) greater than 80 ppbv resulted in increased reports of sore throats, colds, and

absences from school. Goldstein et al. (1988) found that exposure to 300 to 800 ppbv

NO

2

(g) in kitchens reduced lung capacity by about 10 percent. NO

2

(g) may trigger

asthma by damaging or irritating and sensitizing the lungs, making people more sus-

ceptible to allergic response to indoor allergens (Jones, 1999). At mixing ratios

unrealistic under normal indoor or outdoor conditions, NO

2

(g) can result in acute

bronchitis (25 to 100 ppmv) or death (150 ppmv).

3.6.9. Lead

Lead [Pb(s)] is a gray-white, solid heavy metal with a low melting point that is present

in air pollution as an aerosol particle component. It is soft, malleable, a poor conductor

of electricity, and resistant to corrosion. It was first regulated as a criteria air pollutant

in the United States in 1976. Many countries now regulate the emission and outdoor

concentration of lead.

Sources and Sinks

Table 3.15 summarizes the sources and sinks of atmospheric lead. Lead is emitted

during combustion of leaded fuel, manufacture of lead-acid batteries, crushing of lead

STRUCTURE AND COMPOSITION OF THE PRESENT-DAY ATMOSPHERE 75

Table 3.14. Sources and Sinks of Atmospheric Nitrogen Dioxide

Photolysis and kinetic reaction Photolysis and kinetic reaction

Fossil-fuel combustion Dissolution in ocean water

Biomass burning Transfer to soils and ice caps

Sources Sinks

ore, condensation of lead fumes from lead-ore smelting, solid-waste disposal, uplift of

lead-containing soils, and crustal weathering of lead ore. Between the 1920s and the

1970s, the largest source of atmospheric lead was automobile combustion.

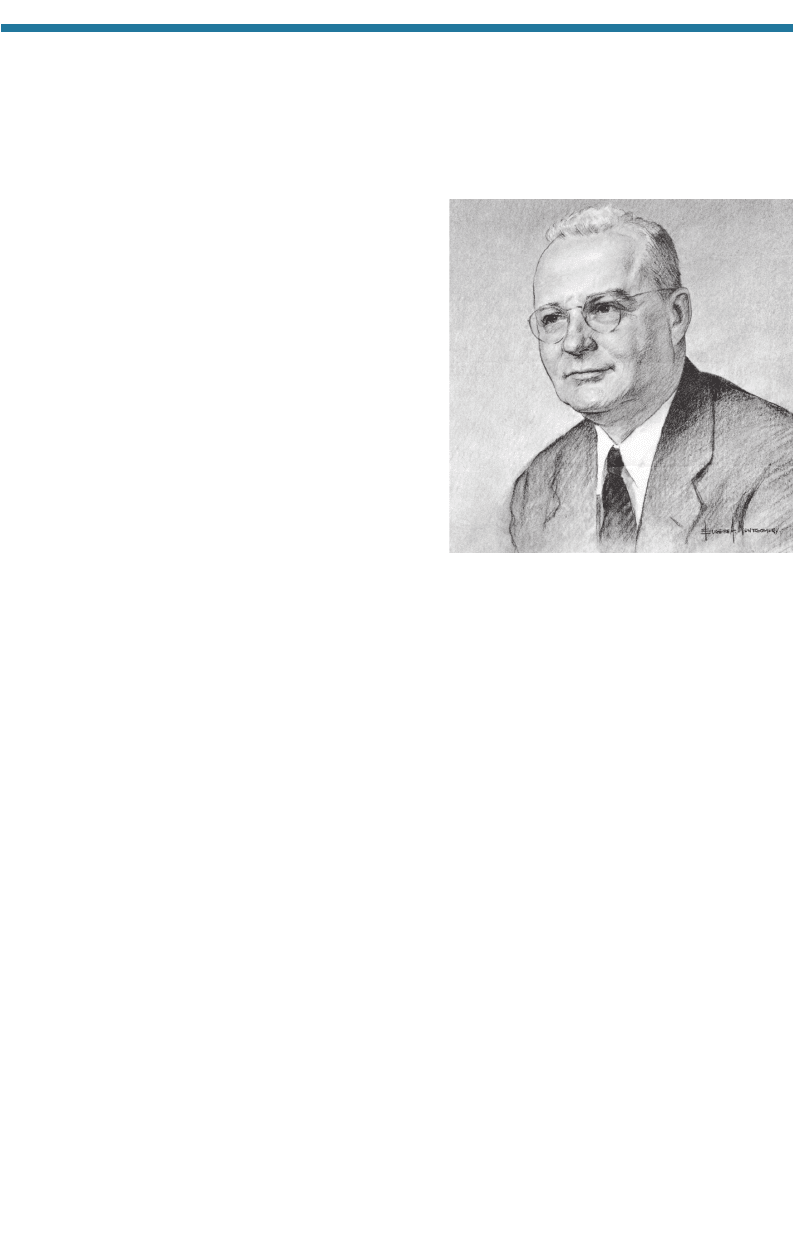

In December 1921, General Motors researcher Thomas J. Midgley Jr. (1889–

1944; Fig. 3.13) discovered that tetraethyl lead was a useful fuel additive for reducing

engine knock, increasing octane levels, and increasing engine power and efficiency in

automobiles. (Midgley later discovered chlorofluorocarbons, CFCs, the precursors to

stratospheric ozone destruction–Section 11.5.1.)

Although Midgley also found that ethanol/benzene blends reduced knock in

engines, he chose to push tetraethyl lead, and it was first marketed in 1923 under the

name “Ethyl gasoline”. That same year, Midgley and three other General Motors

laboratory employees experienced lead poisoning. Despite his personal experience

and warnings sent to him from leading experts on the poisonous effects of lead,

Midgley countered, “The exhaust does not contain enough lead to worry about, but

no one knows what legislation might come into existence fostered by competition

and fanatical health cranks” (Kovarik, 1999,). Between September 1923 and April

1925, 17 workers at du Pont, General Motors, and Standard Oil died and 149 were

injured due to lead poisoning during the processing of leaded gasoline. Five of the

workers died in October 1924 at a Standard Oil of New Jersey refinery after they

became suddenly insane from the cumulative exposure to high concentrations of

tetraethyl lead. Despite the deaths and public outcry, Midgley continued to defend

his additive. In a paper presented at the American Chemical Society conference in

April 1925, he stated

…[T] etraethyl lead is the only material available which can bring about these

[antiknock] results, which are of vital importance to the continued economic

use by the general public of all automotive equipment, and unless a grave and

inescapable hazard exists in the manufacture of tetraethyl lead, its abandon-

ment cannot be justified. (Midgley, 1925)

Midgley’s claim about the lack of antiknock alternatives contradicted his own work

with ethanol/benzene blends, iron carbonyl, and other mixes that prevented knock.

In May 1925, the U.S. Surgeon General (head of the Public Health Service) put

together a committee to study the health effects of tetraethyl lead. The Surgeon

General argued that because no regulatory precedent existed, the committee would

have to find striking evidence of serious and immediate harm for action to be taken

against lead (Kovarik, 1999). Based on measurements that showed lead contents in

fecal pellets of typical drivers and garage workers lower than those of lead-industry

workers, and based on the observations that drivers and garage workers had not

76 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

Table 3.15. Sources and Sinks of Atmospheric Lead

Leaded-fuel combustion Deposition to soils, ice caps,

Lead-acid battery manufacturing and oceans

Lead-ore crushing and smelting Inhalation

Dust from soils contaminated with lead-based paint

Solid-waste disposal

Crustal physical weathering

Sources Sinks

experienced direct lead poisoning, the Surgeon General concluded that there were “no

grounds for prohibiting the use of ethyl gasoline” (U.S. Public Health Service, 1925).

He did caution that further studies should be carried out (U.S. Public Health Service,

1925). Despite the caution, more studies were not carried out for thirty years, and

effective opposition to the use of leaded gasoline

ended.

By the mid-1930s, 90 percent of U.S. gasoline was

leaded. Industrial backing of lead became so strong

that in 1936, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission

issued a restraining order forbidding commercial

criticism of tetraethyl lead, stating that it is

entirely safe to the health of (motorists) and to

the public in general when used as a motor fuel,

and is not a narcotic in its effect, a poisonous

dope, or dangerous to the life or health of a cus-

tomer, purchaser, user or the general public.

(Federal Trade Commission, 1936)

Only in 1959 did the Public Health Service

reinvestigate the issue of tetraethyl lead. At that

time, they found it “regrettable that the investiga-

tions recommended by the Sur

geon General

’s

Committee in 1926 were not carried out by the

Public Health Service” (U.S. Public Health Service,

1959). Despite the concern, tetraethyl lead was not

regulated as a pollutant in the United States until

1976. In 1975, the catalytic converter, which

reduced emission of carbon monoxide, hydrocar-

bons, and eventually oxides of nitrogen from cars,

was invented. Because lead deactivates the catalyst

in the catalytic converter, cars using catalytic con-

verters could run only on unleaded fuels. Thus, the

required use of the catalytic converter in new cars

inadvertently provided a convenient method to phase

out the use of lead. The regulation of lead as a crite-

ria air pollutant in the United States in 1976 due to

its health effects also hastened the phase out of lead

as a gasoline additive. Between 1970 and 1997, total

lead emissions in the United States decreased from

219,000 to 4,000 short tons per year. Table 3.9

shows that, in 1997, only 13.3 percent of total lead

emissions originated from transportation. Today, the

largest sources of atmospheric lead in the United

States are lead-ore crushing, lead-ore smelting, and

battery manufacturing. Since the 1980s, leaded

gasoline has been phased out in many countries,

although it is still an additive to gasoline in several

others.

STRUCTURE AND COMPOSITION OF THE PRESENT-DAY ATMOSPHERE 77

Figure 3.13. Thomas J. Midgley, Jr.

(1889–1944). Inventor of leaded gasoline and

chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), Midgley was born

in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania in 1889. He

grew up in Dayton and Columbus, Ohio, and

graduated from Cornell University with a

degree in Mechanical Engineering in 1911. In

1916, he joined the Dayton Engineering

Laboratories Company (DELCO) as a

researcher. Delco became the main research

laboratory for General Motors in 1919. In

1921, Midgley invented leaded gasoline,

which he named Ethyl. In 1923, he became

vice president of the Ethyl Gasoline

Corporation, a subsidiary of General Motors

and Standard Oil. In 1924, he was forced to

step down due to management problems. He

returned to research on synthetic rubber at

the Thomas and Hochwalt Laboratory in

Dayton, Ohio, with funding from General

Motors. In 1928, Midgley and two assistants

invented chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) as a sub-

stitute refrigerant for ammonia. Midgley

moved on to became vice president of Kinetic

Chemicals, Inc. (1930), dir

ector and vice

president of the Ethyl-Dow Chemical Company

(1933) and director and vice president of the

Ohio State University Research Foundation

(1940–1944). In 1940, he became afflicted

with polio, which became so severe that he

lost a leg and designed a system of ropes to

pull himself out of bed. On November 2,

1944, he died of strangulation in the rope

system. Some consider his death a suicide.