Jacobson M.Z. Atmospheric Pollution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

century. Most prominent was a layer of pollution that formed almost daily in Los

Angeles, California.

In the early twentieth century, this layer was caused by a combination of directly

emitted smoke (London-type smog) and chemically formed pollution, called

photochemical smog. Sources of the smoke were factories, and sources of the

chemically formed pollution were factories and automobiles. In 1903, the factory

smoke was so thick one day that residents of Los Angeles thought they were observing

an eclipse of the sun (SCAQMD, 2000). Figure 4.4 shows a panoramic view of Los

Angeles taken in 1909. The figure shows clouds of dark smoke billowing out of stacks

and traveling across the city. Between 1905 and 1912, regulations controlling smoke

emissions were adopted by the Los Angeles City Council.

88 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

Figure 4.3. Noontime photograph of Donora, Pennsylvania, on October 29, 1948, during a deadly smog

event. Courtesy of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

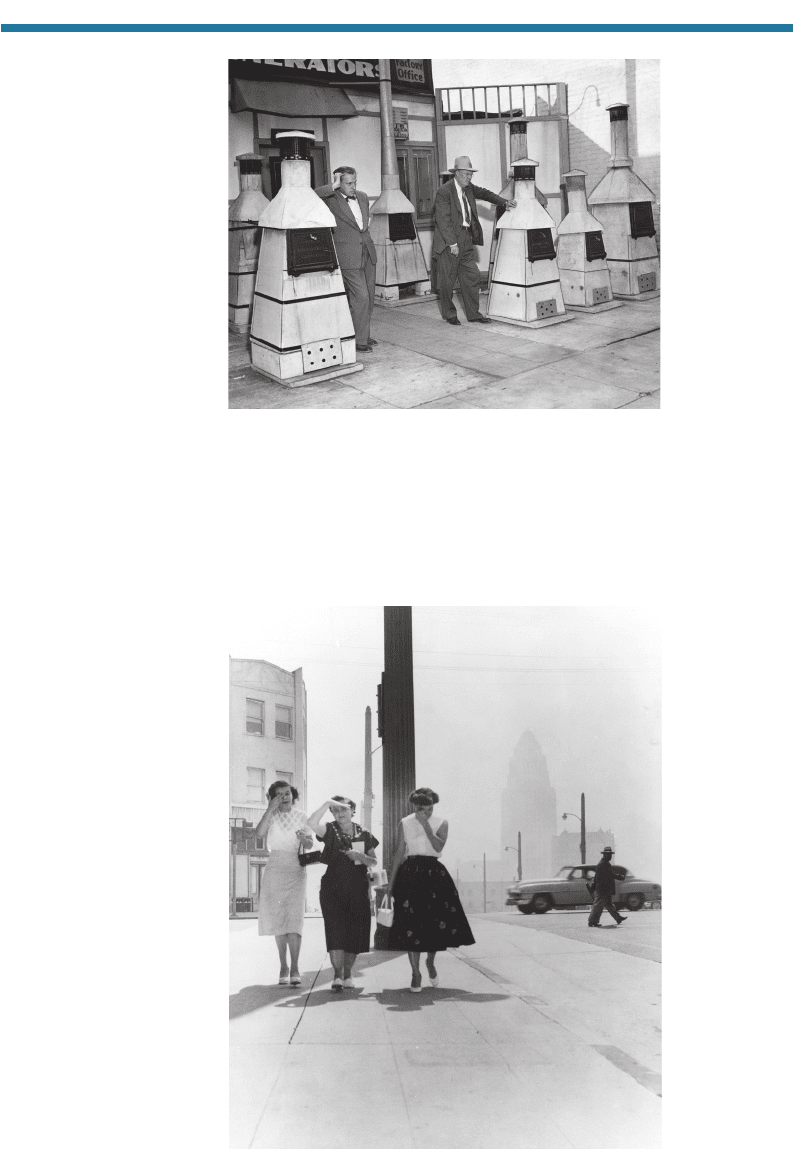

Figure 4.4. Panoramic view of Los Angeles, California, taken from Third and Olive Streets, December 3,

1909. Photo by Chas. Z. Bailey, available from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division,

Washington, DC.

URBAN AIR POLLUTION 89

As automobile use increased, the relative fraction of photochemical versus

London-type smog in Los Angeles increased. Between 1939 and 1943, visibility in

Los Angeles declined precipitously. On July 26, 1943, a plume of pollution engulfed

downtown Los Angeles, reducing visibility to three blocks. Even after a local

Southern California Gas Company plant suspected of releasing butadiene was shut

down, the pollution event continued, suggesting that the pollution was not from that

source.

In 1945, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors banned the emission of

dense smoke and designed an office called the Director of Air Pollution Control. The

city of Los Angeles mandated emission controls in the same year. In 1945, Los

Angeles County Health Officer H. O. Swartout suggested that pollution in Los

Angeles originated not only from smokestacks, but also from other sources, namely

locomotives, diesel trucks, backyard incinerators, lumber mills, city dumps, and auto-

mobiles. In 1946, an air pollution expert from St. Louis, Raymond R. Tucker,was

hired by the Los Angeles

Times to suggest methods of ameliorating air pollution prob-

lems in Los Angeles. Tucker proposed 23 methods of reducing air pollution and

suggested that a countywide air pollution agency be set up to enforce air pollution

regulations (SCAQMD, 2000).

In the face of opposition from oil companies and the Los Angeles Chamber of

Commerce, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors drafted le

gislation to be

submitted to the State of California that would allow counties throughout the state to

set up unified air pollution control districts. The legislation was supported by the

League of California Cities, who felt that air pollution could be regulated more effec-

tively at the county rather than at the city level. The bill passed 73 to 1 in the

California State Legislature and 20 to 0 in the State Assembly and w

as signed by

Governor Earl Warren on June 10, 1947. On October 14, 1947, the Board of

Supervisors created the first regional air pollution control agency in the United States,

the Los Angeles Air Pollution Control District. On December 30, 1947, the district

issued its first mandate, requiring major industrial emitters to obtain emission permits.

In the late 1940s and erly 1950s, the district further regulated open burning in garage

dumps, emission of sulfur dioxide from refineries, and emission from industrial

gasoline storage tanks (1953). In 1954, it banned the 300,000 backyard incinerators

used in Los Angeles (Fig. 4.5). Nevertheless, smog problems in Los Angeles persisted

(Fig. 4.6).

In 1950, 1957, and 1957, Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino counties, respec-

tively, set up their own air pollution control districts. These districts merged with the

Los Angeles district in 1977 to form the South Coast Air Quality Management District

(SCAQMD), which currently controls air pollution in the four-county Los Angeles

region.

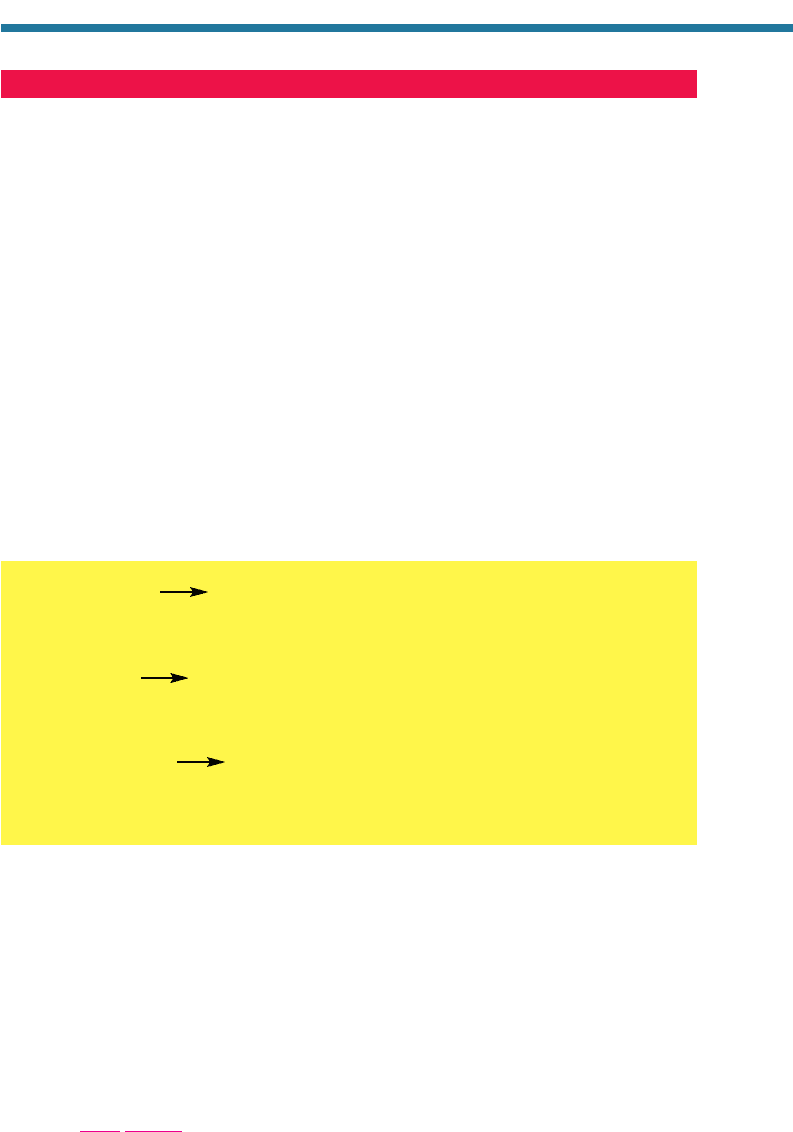

The chemistry of photochemical smog was first elucidated by Arie Haagen-Smit

(1900–1977; Fig. 4.7), a Dutch professor of biochemistry at the California Institute of

Technology. In 1948, Haagen-Smit began studying plants damaged by smog. In

1950, he found that when exposed to ozone sealed in a chamber, plants exhibited the

same type of damage as did plants exposed to outdoor smog, suggesting that ozone

was a constituent of photochemical smog. Haagen-Smit also found that ozone

caused eye irritation, damage to materials, and respiratory problems. Other

researchers at the California Institute of Technology found that rubber, exposed to

high ozone levels, cracked within minutes. In 1952, Haagen-Smit discovered the

90 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

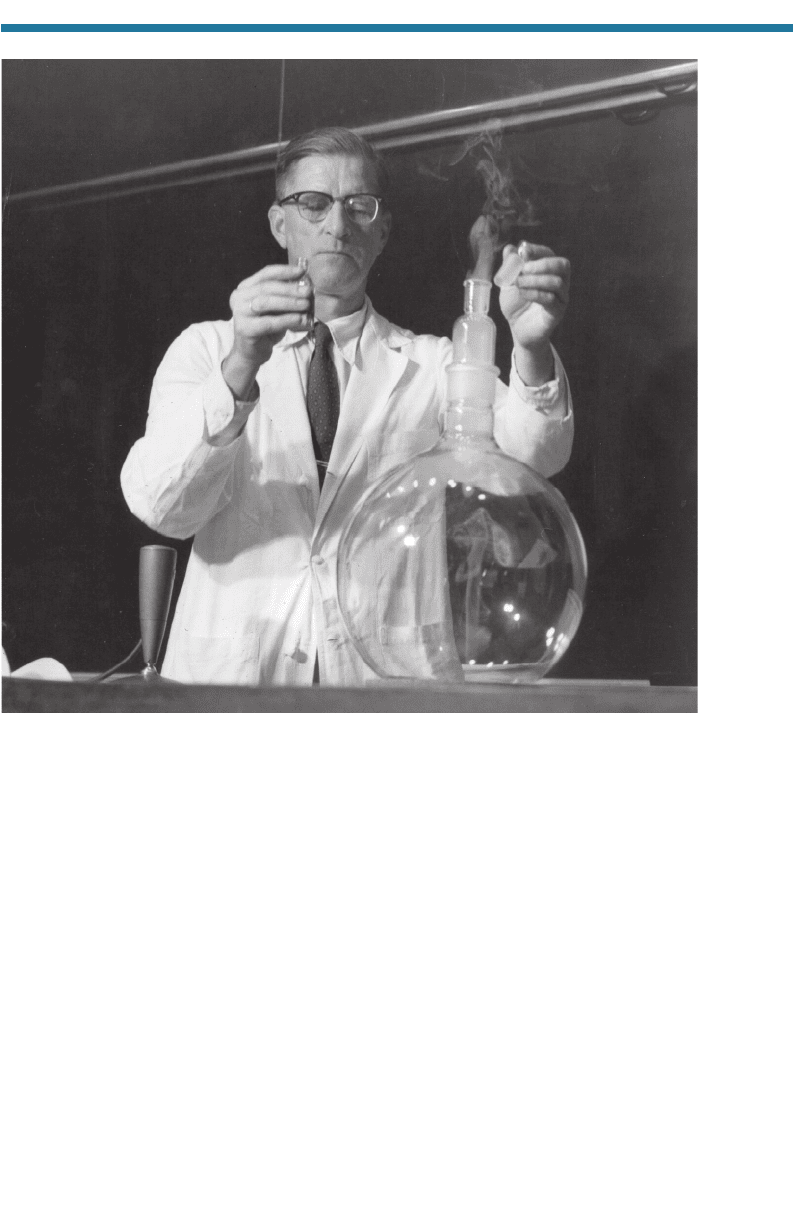

Figure 4.5. Backyard incinerator ban. W. G. Nye and Loy E. Moore, owners of the Peerless

Incinerator Company, show their supply of backyard incinerators as they hear reports of ban-

ning all incinerators. On October 20, 1954, Moore said, “We’re convinced we’re being made

the goats for some other industry.” Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library, Herald-Examiner

Photo Collection.

Figure 4.6. Smog bothers pedestrians. Three women on a sidewalk in downtown Los Angeles in

the mid-1950s are affected by eye irritation due to smog. The building barely visible in the back-

ground is City Hall. Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library, Hollywood Citizens News Collection.

mechanism of ozone formation in smog. In the laboratory, he produced ozone from

oxides of nitrogen and reactive organic gases in the presence of sunlight. He

suggested that ozone and its precursors were the main constituents of Los Angeles

photochemical smog.

On the discovery of the source of ozone in smog, oil companies and business lead-

ers argued that the ozone originated from the stratosphere. Subsequent measurements

showed that ozone levels were low at nearby Catalina Island, proving that ozone in

Los Angeles was local in origin.

Photochemical smog has since been observed in most cities of the world. Notable

sites of photochemical smog include Mexico City, Santiago, Tokyo, Beijing,

Johannesburg, and Athens. Unlike London-type smog, photochemical smog does not

require smoke or a fog for its production. London-type and photochemical smog are

exacerbated by a strong temperature inversion (Section 3.3.1.1). Figure 4.8 shows

photochemical smog in Los Angeles during the summer of 2000.

In the following sections, gas chemistry of background tropospheric air and of

photochemical smog are discussed. Regulatory efforts to control smog since the 1940s

are discussed in Chapter 8.

URBAN AIR POLLUTION 91

Figure 4.7. Arie Haagen-Smit (1900–1977). Courtesy of the Archives, California Institute of

Technology.

92 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

Figure 4.8. Photochemical smog in Los Angeles, California, on July 23, 2000. The smog hides

the high-rise buildings in downtown Los Angeles and the mountains in the background.

URBAN AIR POLLUTION 93

4.2. CHEMISTRY OF THE BACKGROUND TROPOSPHERE

Today, no region of the global atmosphere is unaffected by anthropogenic pollution.

Nevertheless, the background troposphere is cleaner than are urban areas, and to

understand photochemical smog, it is useful to examine the chemistry of the

background troposphere. The background troposphere is affected by inorganic, light

organic, and a few heavy organic gases. The heavy organics include isoprene, a

hemiterpene, and other terpenes emitted from biogenic sources. Urban regions are

affected by inorganic, light organic, and heavy organic gases. Important heavy organics

in urban air, such as toluene and xylene, break down chemically over hours to a few

days; thus, most of the free troposphere is not affected directly by these gases, although

it is affected by their breakdown products. In the following subsections, inorganic and

light organic chemical pathways important in the free troposphere are described.

4.2.1. Photostationary-State Ozone Concentration

In the background troposphere, the ozone [O

3

(g)] mixing ratio is determined primarily

by a set of three reactions involving itself, nitric oxide [NO(g)], and nitrogen dioxide

[NO

2

(g)]. These reactions are

N

•

O(g) O

3

(g) N

•

O

2

(g) O

2

(g)

Nitric Ozone Nitrogen Molecular (4.1)

oxide dioxide oxygen

N

•

O

2

(g) h N

•

O(g) •O

•

(g) 420 nm

Nitrogen Nitric Atomic (4.2)

dioxide oxide oxygen

•O

•

(g) O

2

(g)

M

O

3

(g)

Ground- Molecular Ozone

(4.3)

state atomic oxygen

oxygen

Background tropospheric, mixing ratios of O

3

(g) (20 to 60 ppbv) are much higher

than are those of NO(g) (1 to 60 pptv) or NO

2

(g) (5 to 70 pptv). Because the mixing

ratio of NO(g) is much lower than is that of O

3

(g), Reaction 4.1 does not deplete

ozone during the day or night in background tropospheric air. In urban air Reaction

4.1 can deplete local ozone at night because NO(g) mixing ratios at night may exceed

those of O

3

(g).

If k

1

(cm

3

molecule

1

s

1

) is the rate coefficient of Reaction 4.1 and J (s

1

) is the

photolysis rate coefficient of Reaction 4.2, the volume mixing ratio of ozone can be

calculated from these two reactions as

(4.4)

where

is volume mixing ratio (molecule of gas per molecule of dry air) and N

d

is the

concentration of dry air (molecules of dry air per cubic centimeter). This equation is

called the photostationary-state relationship. The equation does not state that ozone

O

3

(g)

J

N

d

k

1

NO

2

(g)

NO (g)

is affected by only NO(g) and NO

2

(g). Indeed, other reactions affect ozone, including

ozone photolysis. Instead, Equation 4.4 predicts a relationship among NO(g), NO

2

(g),

and O

3

(g). If two of the three concentrations are known, the third can be found from

the equation.

4.2.2. Daytime Removal of Nitrogen Oxides

During the day, NO

2

(g) is removed slowly from the photostationary-state cycle by the

reaction

N

•

O

2

(g) O

•

H(g)

M

HNO

3

(g)

Nitrogen Hydroxyl Nitric (4.5)

dioxide radical acid

Although HNO

3

(g) photolyzes back to NO

2

(g) OH(g), its e-folding lifetime against

photolysis is 15 to 80 days, depending on the day of the year and the latitude.

Because this lifetime is fairly long, HNO

3

(g) serves as a sink for nitrogen oxides

[NO

x

(g) NO(g) NO

2

(g)] in the short term. In addition, because HNO

3

(g) is

soluble, much of it dissolves in cloud drops or aerosol particles before it photolyzes

back to NO

2

(g).

Reaction 4.5 requires the presence of the hydroxyl radical [OH(g)], an oxidizing

agent that decomposes (scavenges) many gases. Given enough time, OH(g) breaks

down every organic gas and most inorganic gases in the air.

The daytime average OH(g) concentration in the clean free troposphere

usually ranges from 2 10

5

to 3 10

6

molecules cm

3

. In urban air, OH(g) concen-

trations typically range from 1 10

6

to 1 10

7

molecules cm

3

. The primary

free-tropospheric source of OH(g) is the pathway

O

3

(g) h O

2

(g) •O

•

(

1

D)(g) < 310 nm

Ozone Molecular Excited

(4.6)

oxygen atomic

oxygen

•O

•

(

1

D)(g) H

2

O(g) 2O

•

H(g)

Excited Water Hydroxyl

(4.7)

atomic vapor radical

oxygen

Thus, OH(g) concentrations in the free troposphere depends on ozone and water vapor

contents.

94 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

EXAMPLE 4.1.

Find the photostationary-state mixing ratio of O

3

(g) at midday when p

d

1013 mb, T 298 K,

J 0.01 s

1

, k

1

1.8 10

14

cm

3

molecule

1

s

1

,

χ

NO(g)

5 pptv, and

χ

NO

2

(g)

10 pptv (typical

free-tropospheric mixing ratios).

Solution

From Equation 3.12, N

d

2.46 10

19

molecules cm

3

. Substituting this into Equation 4.4 gives

χ

O

3

(g)

44.7 ppbv, which is a typical free-tropospheric ozone mixing ratio.

URBAN AIR POLLUTION 95

CO(g) O

•

H(g) CO

2

(g) H

•

(g)

Carbon Hydroxyl Carbon Atomic (4.11)

monoxide radical dioxide hydrogen

H

•

(g) O

2

(g)

M

HO

•

2

(g)

Atomic Molecular Hydroperoxy (4.12)

hydrogen oxygen radical

N

•

O(g) HO

•

2

(g) N

•

O

2

(g) O

•

H (g)

Nitric Hydroperoxy Nitrogen Hydroxyl (4.13)

oxide radical dioxide radical

N

•

O

2

(g) h N

•

O(g) •O

•

(g) 420 nm

Nitrogen Nitric Atomic (4.14)

dioxide oxide oxygen

4.2.3. Nighttime Nitrogen Chemistry

During the night, Reaction 4.2 shuts off, eliminating the major chemical sources of

O(g) and NO(g). Because O(g) is necessary for the formation of ozone, ozone produc-

tion also shuts down at night. Thus, at night, neither O(g), NO(g), nor O

3

(g) is

produced chemically. If NO(g) is emitted at night, it destroys ozone by Reaction 4.1.

Because NO

2

(g) photolysis shuts off at night, NO

2

(g) becomes available to produce

NO

3

(g), N

2

O

5

(g), and HNO

3

(aq) at night by the sequence

N

•

O

2

(g) O

3

(g) N

•

O

3

(g) O

2

(g)

Nitrogen Ozone Nitrate Molecular (4.8)

oxide radical

oxygen

N

•

O

2

(g) NO

•

3

(g)

E

M

N

2

O

5

(g)

Nitrogen Nitrate Dinitrogen (4.9)

dioxide radical pentoxide

N

2

O

5

(g) H

2

O(aq) 2HNO

3

(aq)

Dinitrogen Liquid Dissolved (4.10)

pentoxide water nitric acid

Reaction 4.10 occurs on aerosol or hydrometeor particle surfaces. In the morning, sun-

light breaks down NO

3

(g) within seconds, so NO

3

(g) is not important during the day.

Because N

2

O

5

(g) forms from NO

3

(g) and decomposes thermally within seconds at

high temperatures by the reverse of Reaction 4.9, N

2

O

5

(g) is also unimportant during

the day.

4.2.4. Ozone Production from Carbon Monoxide

Daytime ozone production in the free troposphere is enhanced by carbon monoxide

[CO(g)], methane [CH

4

(g)], and certain nonmethane organic gases. CO(g) produces

ozone by

96 ATMOSPHERIC POLLUTION: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND REGULATION

CH

4

(g) O

•

H(g) C

•

H

3

(g)

2

O(g)

Methane Hydroxyl Methyl Water (4.16)

radical radical vapor

C

•

H

3

(g) O

2

(g)

M

CH

3

O

•

2

(g)

Methyl Molecular Methylperoxy (4.17)

radical oxygen radical

N

•

O(g) CH

3

O

•

2

(g) N

•

O

2

(g) CH

3

O

•

(g)

Nitric Methylperoxy Nitrogen Methoxy (4.18)

oxide radical dioxide radical

N

•

O

2

(g) h N

•

O(g) •O

•

(g) 420 nm

Nitrogen Nitric Atomic (4.19)

dioxide oxide oxygen

•O

•

(g) O

2

(g)

M

O

3

(g)

Ground- Molecular Ozone

(4.20)

state atomic oxygen

oxygen

•O

•

(g) O

2

(g)

M

O

3

(g)

Ground- Molecular Ozone

(4.15)

state atomic oxygen

oxygen

Because the e-folding lifetime of CO(g) against breakdown by OH(g) in the free tropo-

sphere is 28 to 110 days, the sequence does not interfere with the photostationary-state

relationship among O

3

(g), NO(g), and NO

2

(g). The second reaction is almost instanta-

neous. Reaction 4.11 not only leads to ozone formation, but also produces carbon dioxide.

4.2.5. Ozone Production from Methane

Methane [CH

4

(g)], with a mixing ratio of 1.8 ppmv, is the most abundant organic gas

in the Earth’s atmosphere. Its free-tropospheric e-folding lifetime against chemical

destruction is 8 to 12 years. This long lifetime has enabled it to mix uniformly up to

the tropopause. Above the tropopause, its mixing ratio decreases. Methane’s most

important tropospheric loss mechanism is its reaction with the hydroxyl radical. The

methane loss pathway produces ozone, but the incremental quantity of ozone produced

is small compared with the photostationary quantity of ozone. The methane oxidation

sequence producing ozone is

In the first reaction, OH(g) abstracts (removes) a hydrogen atom from methane,

producing the methyl radical [CH

3

(g)] and water. In the stratosphere, this reaction is

an important source of water vapor. As with Reaction 4.12, Reaction 4.17 is fast. The

remainder of the sequence is similar to the remainder of the carbon monoxide

sequence, except that here, the methylperoxy radical [CH

3

O

2

(g)] converts NO(g) to

URBAN AIR POLLUTION 97

NO

2

(g), whereas in the carbon monoxide sequence, the hydroperoxy radical [HO

2

(g)]

performs the conversion.

4.2.6. Ozone Production from Formaldehyde

An important byproduct of the methane oxidation pathway is formaldehyde [HCHO(g)].

Formaldehyde is a colorless gas with a strong odor at higher than 0.05 to 1.0 ppmv. It is

the most abundant aldehyde in the air and moderately soluble in water. Aside from gas-

phase chemical reaction, the most important source of formaldehyde is emission from

plywood, resins, adhesives, carpeting, particleboard, fiberboard, and other building mate-

rials (Hines et al., 1993). Mixing ratios of formaldehyde in urban air are generally less

than 0.1 ppmv (Maroni et al., 1995). Indoor mixing ratios range from 0.07 to 1.9 ppmv,

and typically exceed outdoor mixing ratios (Anderson et al.,

1975; Jones, 1999).

Because formaldehyde is moderately soluble in water, it dissolves readily in the

upper respiratory tract. Below mixing ratios of 0.05 ppmv, formaldehyde causes no

known health problems; at 0.05 to 1.5 ppmv, it has neurophysiologic effects; at 0.01 to

2.0 ppmv, it causes eye irritation; at 0.1 to 25 ppmv, it causes irritation of the upper

airway; at 5 to 30 ppmv, it causes irritation of the lower airway and pulmonary

problems; at 50 to 100 ppmv, it causes pulmonary edema, inflammation, and pneumo-

nia; and at greater than 100 ppmv, it can result in a coma or be fatal (Hines et al.,

1993; Jones, 1999). Formaldehyde is but one of many eye irritants in photochemical

smog. Compounds that cause eyes to swell, redden, and tear are lachrymators. The

methoxy radical from Reaction 4.18 produces formaldehyde by

CH

3

O

•

(g) O

2

(g) HCHO(g) HO

•

2

(g)

Methoxy Molecular Formal- Hydroperoxy (4.21)

radical oxygen dehyde radical

The e-folding lifetime of CH

3

O(g) against destruction by O

2

(g) is 10

4

seconds. Once

formaldehyde forms, it produces ozone precursors by

(4.22)

HCHO(g) O

•

H(g) HC

•

O(g)

2

O(g)

Formal- Hydroxyl Formyl Water (4.23)

dehyde radical radical vapor

HC

•

O(g) O

2

(g) CO(g) HO

•

2

(g)

Formyl Molecular Carbon Hydroperoxy (4.24)

radical oxygen monoxide radical

H

•

(g) O

2

(g)

M

HO

•

2

(g)

Atomic Molecular Hydroperoxy (4.25)

hydrogen oxygen radical

Carbon

monoxide

HCHO(g) + hν

λ < 334 nm

λ < 370 nm

HCO(g) + H(g)

Formyl Atomic

radical hydrogen

CO(g) + H

2

(g)

Formal-

dehyde

Molecular

hydrogen