Hess Earl J. Field Armies and Fortifications in the Civil War: The Eastern Campaigns, 1861-1864

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

138 Second Manassas, Antietam, and Maryland

provided statistics on the ranges of several landmarks in Washington—such

as the White House and the Capitol—from across the Potomac River at Ar-

lington. Apparently he hoped Lee would invade Maryland, invest the North-

ern capital, or at least shell Washington—anything to pay back the Yankees

for the threat they had pressed against Richmond the preceding spring.

∞∑

While Lee had no intention of attacking Washington, he hatched plans for

a bold invasion of Northern-held territory. Maryland had never formally

seceded from the Union, but this border slave state was vulnerable now that

Pope’s army was streaming back to the capital and much of McClellan’s army

was still en route from the Peninsula. The authorities, not privy to Lee’s

plans, naturally became alarmed for the safety of the city. Not since the

aftermath of First Manassas had Washington been thrown into such a panic.

The city became a refuge for Pope’s defeated army, but organization was

soon brought out of chaos when McClellan assumed command of the city

defenses on September 3. He moved the rest of the Army of the Potomac

to the region and organized a campaign into Maryland, leaving Maj. Gen.

Nathaniel Banks in charge of the city defenses. There were plenty of men,

some 46,000 veterans of Pope’s army and more than 15,000 garrison troops.

The equivalent of an entire field army hovered around the capital for the rest

of the fall, providing labor for a massive expansion of the defense system and

needed improvement of what had already been built.

With so many resources and the apparent need for protection, Secre-

tary of War Edwin Stanton appointed a commission in October 1862 to rec-

ommend what should be done on the works. Consisting of Engineer Chief

Joseph G. Totten, John G. Barnard, Quartermaster Gen. Montgomery C.

Meigs, and George W. Cullum, Halleck’s chief of staff, the commission stud-

ied the problem for two months and issued a report on Christmas eve. The

commission approved what had already been done but recommended half a

dozen new forts and improved infantry lines between the works. It also

recommended a permanent garrison of 25,000 infantrymen, 9,000 artil-

lerymen, and 3,000 cavalrymen. Barnard reported that $100,000 had been

spent on the works during the last five months of 1862, and he believed

another $200,000 would be needed to complete the work recommended by

the commission. This was a large sum when added to the $550,000 spent

before the summer of 1862, yet the government readily endorsed the com-

mission’s suggestions.

∞∏

Even as the commission deliberated, Barnard set the soldiers to work.

They cut timber to clear fields of fire and improved the existing works. Alfred

Bellard of the 5th New Jersey helped to build a new fort using the method

outlined by the engineer manuals. Light pieces of wood were used to con-

Second Manassas, Antietam, and Maryland 139

struct a frame exactly outlining, in three dimensions, the shape and size of

the parapet. The soldiers dug a deep and wide ditch and used the dirt to fill

this frame, tamped it to make the parapet solid, and then sodded it. The

ditch eventually filled with water from rainfall, and obstructions were fitted

in front of the work.

∞π

Barnard supervised additional work on the fortifications in early 1863. By

then there were far fewer soldiers available, and the engineer had to hire

squads of civilian laborers (and foremen to oversee their work)—as many as

1,000 at a time. The civilians were paid more than a dollar per day. He also

hired up to forty carpenters to manufacture wooden structures. This was the

last phase in the creation of the Washington defenses. A total of sixty-eight

forts and batteries, ninety-three unarmed field gun batteries, three block-

houses, and twenty miles of infantry trench constituted the most extensive

system of fortifications to guard a single location in American history. The

line around the national capital totaled thirty-seven miles in length. Not only

in their massive size but in their precision and adherence to regulations were

the Washington defenses ‘‘the showpiece effort of the Engineers,’’ according

to a modern historian.

∞∫

The works created such a huge demand for troops that the Department of

Washington was organized in February 1863. The personnel were termed the

Twenty-Second Corps, and Maj. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman was put in

charge. He had nearly 62,000 men at first, but the number had dwindled to

44,000 by April and to 32,000 by June due to transfers to the Army of the

Potomac. The defenses tied these men to safe but monotonous duty in a

position that was far too strong for any sane general to contemplate an

attack. The works protected the capital well, but they were bigger, more

extensive, and more demanding of troops than necessary. When Grant came

east to command all Union troops, he stripped the defenses of their man-

power to maximize strength for the spring campaign against Lee in 1864.

∞Ω

Lee’s Maryland Campaign

Lee crossed the Potomac River on September 4 and occupied Frederick.

He expected the Federals holding the lower end of the Shenandoah Valley at

Harpers Ferry and Martinsville to retire so he could use the Valley as his line

of communications, but Halleck ordered those men to hold on. It was the

decisive factor in the coming campaign, for the rest of Lee’s movements

would be oriented around clearing the Valley path for his supplies.

Lee’s plan to eliminate the roadblock in the Valley was issued to his com-

manders on September 9. He divided the army into four parts, three of

which were to make rapid movements to Harpers Ferry, reduce the place,

140 Second Manassas, Antietam, and Maryland

and rejoin him at Boonsboro about twenty miles north of Harpers Ferry.

They had three days to accomplish the task. Jackson led one of the three col-

umns, 14,000 men, from Frederick on September 10. He was to occupy the

high ground called Bolivar Heights on the west side of Harpers Ferry, while

Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws and 8,000 men occupied Maryland Heights on

the north side of the Potomac River. The third column, 2,400 men under

Brig. Gen. John George Walker, was to take Loudoun Heights east of the

Shenandoah River.

≤≠

Harpers Ferry

Few other engagements of the war would be so dominated by the terrain

of the battlefield as this one. Harpers Ferry, an old and important arsenal

town at the confluence of the Potomac River and the Shenandoah River, was

nestled among some of the most imposing mountains in the eastern theater.

The Potomac River was the only waterway powerful enough to cut through

the mountains as plate tectonics created them millions of years ago. Thus the

gap at Harpers Ferry is the only deep-water gap in the Blue Ridge. The flow

of the Shenandoah River, the largest tributary of the Potomac, was diverted

when the Blue Ridge rose up. All other smaller streams in the area also were

redirected by the rise of the mountains to flow into the Shenandoah or the

Potomac, leaving many so-called wind gaps in the mountaintops. They are

the remnants of stream erosion, cut slightly into the emerging mountaintop

before the water was diverted. The combination of plate movement and

hydrography created a rugged, natural arena with the town of Harpers Ferry

as the stage.

The most important high ground is Maryland Heights, which is part of the

Blue Ridge. The heights are the end of a long, wide, and high ridge that

stretches many miles from the north. The elevation of Maryland Heights

ranges from 1,300 to 1,400 feet, almost 1,000 feet higher than the land beside

it. The end of Maryland Heights points directly toward the junction of the

two rivers. On the other side of that junction, the Blue Ridge continues with

Loudoun Heights, which constitutes the modern boundary between Virginia

and West Virginia. West of Harpers Ferry, Bolivar Heights is a ridge some 700

feet tall, about 300 feet higher than the town itself. Bolivar Heights is a

superb defensive position screening the approach to Harpers Ferry. All this

high ground surrounding the town would be a wonderful defensive position

if adequately fortified and manned, but that would require thousands of

troops. If left unguarded, the high ground on each of the three sides can

doom the position by allowing enemy forces to dominate the town with

artillery fire. This would be the key to Confederate success.

≤∞

Second Manassas, Antietam, and Maryland 141

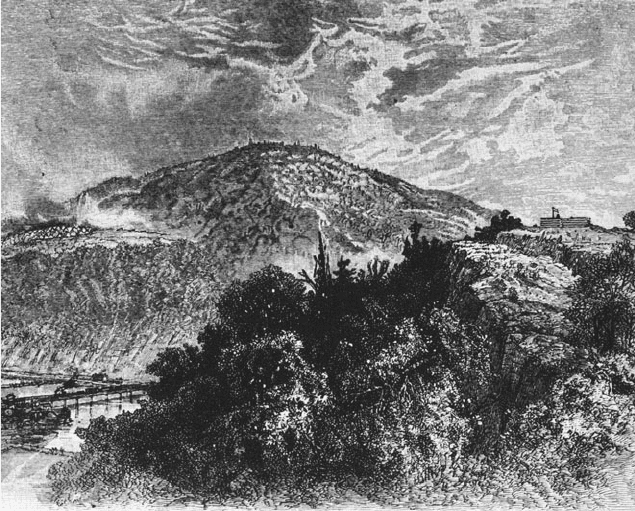

Loudoun Heights and Maryland Heights, Harpers Ferry. Note the timber stockade and

signal station on Loudoun Heights on the right and the commanding position of

Maryland Heights in the background. The naval battery was located on the plateau on

the left. (Johnson and Buel, Battles and Leaders, 2:608).

The mountaintops had a thick layer of original trees until the 1840s, when

extensive cutting took place to produce charcoal. By the time of the war, the

heights were covered by a second growth of scrubby timber and underbrush.

Confederate troops commanded by Jackson occupied Harpers Ferry in April

1861, and 500 of them took possession of Maryland Heights on May 9. They

cleared an area on top and erected a stockade, but Gen. Joseph E. John-

ston evacuated Harpers Ferry in mid-June 1861. Union captain John Newton

scouted the heights when the Federals took possession and reported that the

vegetation was so thick as to be ‘‘difficult of penetration.’’ This led Federal

commanders to defer extensive fortification on the high ground, but they

could hardly ignore the strategic significance of the heights. When Jackson’s

Valley campaign was in full swing in May 1862, Federal engineers hastily laid

out the naval battery, manned by gunners from the Washington Navy Yard. It

was located on a plateau one-third of the way up Maryland Heights and

could fire on almost any spot in town as well as on Bolivar Heights. It had

142 Second Manassas, Antietam, and Maryland

seven gun emplacements, and the parapet was made mostly of sandbags. An

old road built before the war by charcoal and quarry workers was used to

gain access to the site, some 400 feet above the Potomac.

≤≤

In September, Jackson would be greatly aided by the incompetence of his

opponent, for Harpers Ferry was under the command of Col. Dixon S. Miles.

Born in 1804 and a graduate of West Point, Miles already had a checkered

war career. Hit with dysenteric diarrhea just before First Bull Run, he took

quinine, opium, and brandy and was visibly inebriated during the engage-

ment. A court of inquiry failed to find evidence to convict him, so he re-

mained on duty. Miles was shifted to the quiet post in March 1862, but he did

little to fortify it beyond constructing the naval battery. Under pressure from

department commander John E. Wool, Miles also erected a line of infantry

trench on Camp Hill, a modest elevation between Bolivar Heights and the

town. Wool’s instructions to build a blockhouse on Maryland Heights, lay

abatis in front of the work on Camp Hill, and entrench a camp on Bolivar

Heights were never followed.

Miles had 11,000 men at Harpers Ferry, organized into brigades, but most

were green troops who had never been tested in battle. As the three Confed-

erate columns converged on the place, Brig. Gen. Julius White brought an

additional 2,500 men from Martinsburg on September 12. Although White

outranked Miles, he gave up command of the post and its threatened gar-

rison to the colonel.

≤≥

The faulty dispositions of this incompetent officer gave Jackson his oppor-

tunity to seize the heights. Miles put three of his four brigades west of town,

two on Bolivar Heights and another on Camp Hill to support a battery of

fourteen guns. The last brigade, under Col. Thomas Ford, was placed in an

isolated position on Maryland Heights. Ford constructed a line of breast-

works consisting of logs and rocks, and he cut trees to form an abatis in front.

Loudoun Heights was left unoccupied.

≤∂

On September 12, the day that White reached Harpers Ferry, McLaws

ascended Maryland Heights. He advanced to Ford’s line of breastworks

and stopped for the night. Although his forces greatly outnumbered Ford’s,

McLaws gingerly advanced on the morning of September 13, outflanked the

line, and forced the Unionists to retreat. The Federals regrouped a quarter of

a mile away while McLaws halted. A stalemate ensued for several hours.

Then, at midafternoon, Ford apparently misunderstood an order from Miles

and took his entire brigade off Maryland Heights. McLaws most likely would

have taken the high ground anyway, but Ford’s withdrawal offered Jackson

the key to Harpers Ferry.

September 13 was a momentous day for many commanders in this cam-

Second Manassas, Antietam, and Maryland 143

paign. As McLaws secured Maryland Heights, Jackson’s column approached

Bolivar Heights and Walker’s column ascended Loudoun Heights. Many

miles to the east, McClellan received a copy of Lee’s Special Orders No. 191,

which outlined the Harpers Ferry operation and showed that Lee himself

commanded what little remained of the Army of Northern Virginia in west-

ern Maryland. A copy of the order had been found wrapped around three

cigars in an abandoned Rebel camp. McClellan decided to push westward,

force his way through the passes of South Mountain (the continuation of the

Blue Ridge north of the Potomac River), and hit Lee before Jackson could

rejoin him. He also dispatched Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin’s Sixth Corps to

relieve Harpers Ferry. McClellan delayed the start of his movements until the

next day, giving both Lee and Jackson more time to accomplish their goals.

≤∑

With Jackson’s column blocking Miles’s escape on the west and McLaws

busily planting guns on Maryland Heights, it was up to Walker to complete

the investment of Harpers Ferry. He reached the foot of Loudoun Heights at

10:00 a.m. on September 13 and dispatched two regiments to the top. They

found the summit unoccupied. That evening Lt. William G. Williamson and

another engineer officer scouted the rocky top for good artillery positions.

Williamson sketched a map and sent it to Jackson by courier, and he sup-

plemented it with another sketch and verbal information when he saw Jack-

son the next morning. The commander approved, and Williamson again

ascended the heights to supervise the construction of battery emplacements

on September 14. Walker placed five Parrotts on Loudoun Heights that day,

and McLaws planted six guns on top of Maryland Heights. Jackson estab-

lished his batteries on School House Ridge, a lower but well-defined feature

about 1,000 yards in front of Bolivar Heights.

Jackson used signal flags to communicate with McLaws and Walker, in-

tending to coordinate the opening of his bombardment, but Walker grew

impatient and opened without orders at 2:00 p.m. on September 14. This

compelled Jackson and McLaws to commence firing. The Confederate artil-

lery dominated the poorly placed Union guns, but the Federal infantry was

well protected by ravines and suffered comparatively little. While the guns

roared, A. P. Hill’s division moved forward to find an opening on the south

end of Bolivar Heights. A shelf of bottomland along the river allowed him to

flank the Union forces on the high ground and plant some guns in prepara-

tion for an attack the next day. Only a line of abatis stood in Hill’s way.

≤∏

On September 14, after a day of hard fighting, McClellan broke through

three passes in South Mountain. This development compelled Lee to plan a

retreat to Virginia. He sent orders to McLaws to give up the siege of Harpers

Ferry and rejoin the army in the vicinity of Sharpsburg. But Jackson assured

144 Second Manassas, Antietam, and Maryland

Lee that he could compel the surrender of the garrison on September 15, and

the army commander relented. McLaws dispatched some units northward to

block Franklin’s advance toward Harpers Ferry, and fifty cannon resumed

the bombardment of Miles’s isolated command on the morning of Septem-

ber 15. Soon the Federal guns ran out of long-range ammunition, and Miles

surrendered. White flags were raised, but one of the last Confederate shells

mortally wounded Miles. White assumed command and negotiated the sur-

render. Jackson captured 12,500 men and seventy-three guns but lost only

286 men. Only 217 Unionists were killed and wounded. The Northerners

were outnumbered, inadequately fortified, and ineptly led, and their loss of

supplies and prestige was enormous.

≤π

South Mountain

After Lee dispatched the three columns to take Harpers Ferry, he moved

his remaining three divisions—two of Longstreet’s and one commanded by

D. H. Hill—to Hagerstown and Boonsboro. The loss of Special Orders No. 191

gave McClellan the information needed to move on these divisions, but the

Union commander delayed half a day before acting. He did not expect much

resistance at the passes of South Mountain and thus was unprepared for a

major battle. Lee received word from his cavalry on the night of September

13 that the Federals were beginning to move, so he dispatched D. H. Hill to

take charge of the position on South Mountain. Hill had only two of his five

brigades in place when the battle started the next morning.

South Mountain, which rises from 1,000 to 1,300 feet above the valleys to

either side of it, is the eastern edge of the Appalachian Highlands north of

the Potomac River. Between Frederick and Hagerstown there are four cross-

ings: Turner’s Gap, through which the National Road traversed the moun-

tain; Fox’s Gap; Crampton’s Gap; and Brownsville Gap. The first two are less

than a mile apart, while Crampton’s and Brownsville gaps are about five

miles south. The slopes of South Mountain are steep and rugged, especially

near the top. This was the only battle in which the Army of the Potomac had

to contend with Appalachian terrain, even though units of that army had

fought in the mountains of western Virginia and most regiments that surren-

dered at Harpers Ferry would later join the army as well.

≤∫

The Ninth Corps of McClellan’s army tried to force its way through Fox’s

Gap, the second pass from the north, at 9:00 a.m. The slope there ascended

sharply for about 300 yards and then gave way to a more moderate slope

before a sharper ascent was resumed. The gap itself is wide and deep, cutting

through about half the height of the mountain. The Federals found remark-

ably open terrain, much of it farmland, as they neared the top. Regular battle

Second Manassas, Antietam, and Maryland 145

lines could be drawn here, and Brig. Gen. Samuel Garland’s North Carolina

brigade fought well. The Rebels eventually were pushed back to the crest

and beyond, where Garland’s men took shelter in a road that was sunken a

couple of feet deep and bordered by a stone fence. This was an effective

fortification even though it allowed the Rebels to see only about fifty yards to

their front; beyond that point, the natural crest of the mountain shielded the

attackers. Garland was killed, and one-third of his command, which was

outnumbered three to one, fell; even some hand-to-hand fighting took place.

Additional brigades from both Hill and Longstreet stalled the Federal ad-

vance in the afternoon and prevented the Ninth Corps from exploiting its

advantage, but the gap was essentially in Union hands.

≤Ω

Farther to the south the Sixth Corps was assigned to crash through Cramp-

ton’s Gap and relieve Harpers Ferry, but Franklin dithered. Initially only four

regiments, aligned behind a stone fence near the base of the mountain,

defended the pass. The land in front of Crampton’s Gap is open, rolling, and

pastoral; but the slope is very steep, and the gap itself is comparatively

shallow, cutting down through about one-fourth of the eminence. The Rebels

were placed at the base of the mountain where the lowest part of the slope

met the surrounding countryside. They should have been farther up, to force

the Federals to traverse the steep slope, but there was no good terrain feature

like a stone fence on the mountainside. Franklin bombarded the position for

two hours and then launched an infantry assault at 4:00 p.m. that easily

pushed the Confederates up the mountain toward the gap. The Federals

occupied the pass as dusk descended, but it was too late to go farther.

≥≠

Turner’s Gap, on the far north, presented the most difficult terrain. The

National Road approached the gap through a deep gorge that was wide and

spacious at the bottom but quickly narrowed, with steep sides, as it neared

the top. The gap itself is also narrow, cutting down through one-fourth of the

mountain. When the First Corps approached this imposing obstacle, Brig.

Gen. George G. Meade’s division was sent up a road that ascended a spur to

the north of Turner’s Gap. Meade was to outflank the gap by gaining access

to the mountaintop just to the north. He was separated from the rest of the

corps by a deep ravine, so Brig. Gen. John P. Hatch’s division advanced up

the same spur but south of the ravine. A lone Alabama brigade, led by Brig.

Gen. Robert E. Rodes, faced both Yankee divisions. Rodes put up a hard fight

and lost one-third of his men, but he delayed Meade and Hatch for some

time. While this slow ascent was taking place, Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s

brigade launched a spirited attack up the National Road toward the gap.

Brig. Gen. Alfred H. Colquitt’s Georgia brigade blocked the way at a stone

fence and stopped Gibbon near dusk before he could capture the gap. That

146 Second Manassas, Antietam, and Maryland

successful defense would soon be wasted, for Meade and Hatch had nearly

completed their turning movement by pushing Rodes back to the mountain-

top. The next morning, they would be in position to seize Turner’s Gap.

≥∞

By the time the fighting had ended, all of McClellan’s army was on the

battlefield. If he could have accomplished this at dawn and then moved

swiftly, the passes probably would have been forced more easily. McClellan’s

half-day delay after he found Lee’s lost order had given the Rebel com-

mander time to shift large numbers of men to the passes by midafternoon,

and the swift movement to a decisive showdown with Lee west of South

Mountain was no longer possible. Instead, McClellan was forced into a heavy

battle merely to secure possession of the gaps.

More than 2,000 men were lost by both sides in this battle on September

14, the day that Jackson was getting the upper hand on Miles at Harpers

Ferry. When one surveys the battlefield today, a question naturally arises:

Why did the Confederates not use this immense natural feature to block

McClellan’s advance indefinitely? In short, why did Lee not dig in before

September 14? Even small detachments behind good works could have de-

layed any Union force moving westward and given him more time to concen-

trate his army west of South Mountain. Rather like Pope and Thoroughfare

Gap at Second Bull Run, Lee neglected to use earthworks at a natural bottle-

neck that could have paid rich strategic dividends.

Antietam

Lee fought a defensive battle at Sharpsburg even though the terrain of-

fered few advantages to his outnumbered army. With only 35,000 men at the

start of the engagement, he arrayed his divisions so as to reap every pos-

sible benefit from the landscape. The ground between Antietam Creek and

Sharpsburg is open, rolling farmland, with numerous limestone ledges and

outcroppings. The inequalities in the land are relatively modest. The bed of

Antietam Creek lay at an elevation of 320 feet, Sharpsburg was at 480 feet,

and the tops of the rolling hills did not exceed 520 feet. It was more wooded in

1862, when significant patches of trees dotted the northern section of the bat-

tlefield, than it is today, but the ground offered opportunity for artillery con-

centrations and for the rapid movement of large masses of infantrymen.

≥≤

Lee did not dig in, although there was time and opportunity to do so.

Good fieldworks would have been amply justified, considering the disparity

of numbers and the open nature of the terrain. It is true that the topsoil is

shallow—only five inches in some places—but there were fence rails and

stones that could have been used to make breastworks. Historian Edward

Hagerman has suggested that Lee demonstrated his adherence to ‘‘an ex-

Second Manassas, Antietam, and Maryland 147

treme tendency in American tactical thought that opposed all fortifications

in the open field of battle’’ because it would hinder ‘‘the resumption of the

offensive.’’ This is probably true. Lee wanted to keep his tactical options open

when the clash took place. Antietam fits nicely into the trend many Civil War

commanders displayed. They were eager to dig in during the first half of the

war only when they occupied rough terrain that in itself inhibited tactical

movement, but in open ground they did not want to tie their forces down un-

necessarily to the defensive. McClellan also did not fortify when he reached

the vicinity. Hagerman wonders if he was ‘‘intimidated by the criticism’’ of

his reliance on fortifications during the Peninsula campaign, but it is more

likely that he intended to assume the tactical offensive as soon as possible.

McClellan knew he had to attack, and there was no reason to dig works. Even

on the Peninsula and in the Seven Days, he had always demonstrated a

tendency to dig in only when needed.

≥≥

The battle fought on September 17 was one of the most costly of the war,

and the Confederates tried to make good use of existing topographical fea-

tures as cover. The rocky outcroppings, the ravines, and the woods them-

selves offered some protection. The fight started on the northern part of the

field when the First Corps of the Army of the Potomac emerged from North

Woods and struck Jackson’s men, newly arrived from Harpers Ferry, in the

area of farmer Miller’s cornfield. The Federals crossed a ravine that sepa-

rated the woods from the field and entered the ripening stand of corn. The

only fortification thrown up on this part of the field by the Confederates was

a small breastwork in the pasture south of the field. The fighting swayed

back and forth through and around this patch of corn until the stalks were

shot down, broken over, and trampled by thousands of feet. Attacks and

counterattacks failed to result in a decisive advantage for either side but

littered the countryside with casualties.

Soon after the First Corps started, the Twelfth Corps supported it to the

left by attacking from East Woods. This corps was led by an engineer officer,

Maj. Gen. Joseph K. F. Mansfield, who had never commanded in combat.

Mansfield had lobbied for a field assignment for some time and took over the

Twelfth Corps on September 15. Half of his 7,200 men were just as green as

he was, but they all fought well, duplicating the tactical experience of their

comrades to the right. The Rebels on this part of the line found several

opportunities to take advantage of the inequalities of the ground. Capt.

Thomas M. Garrett of the 5th North Carolina reported that his men came up

to ‘‘a ledge of rock and earth, forming a fine natural breastwork,’’ and held

there until they were outflanked and forced to retire. Mansfield was shot in

the chest early in the advance and died the next day.

≥∂