Hess Earl J. Field Armies and Fortifications in the Civil War: The Eastern Campaigns, 1861-1864

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

158 Fredericksburg

concentrated artillery fire, 120 men of the 7th Michigan set out in six pon-

toons rowed by men from the 50th New York Engineers. Several were hit in

crossing, but the rest landed and took a number of buildings. Another con-

tingent of infantry from the 89th New York went over to help, and soon the

way was clear to finish the bridge. Woodbury lost 7 killed and 43 wounded

bridging the river.

π

The other bridges were less costly and time consuming to build. One of

them was nearly finished at 8:15 a.m. when Rebel fire forced a delay, but the

artillery managed to clear enough Confederates from that part of the west

bank to allow the engineers to finish it by 9:00 a.m. Two bridges were built

the next day, making a total of five to cross Burnside’s army.

∫

The Confederates strengthened their artillery emplacements on Decem-

ber 11, building embrasures and raising parapets and traverses a bit higher.

‘‘The engineers objected, and said they were ‘ruining the works,’ ’’ recalled

William Owen of the Washington Artillery, ‘‘but the cannoneers said, ‘We

have to fight here, not you; we will arrange them to suit ourselves.’ ’’ Long-

street agreed with his gunners, saying, ‘‘ ‘If you save the finger of a man’s

hand, that does some good.’ ’’

Ω

But the guns could do little to hinder the bridge builders as Barksdale’s

men provided most of the resistance that delayed the laying of the pontoons.

They made good use of cover. General Woodbury found a house that had

loopholes cut into it only a few yards from the spot where the upper bridge

reached the west bank. A stone wall nearby had been used by the Mississip-

pians, and cellars with windows cut through stout masonry foundations

made good blockhouses. The Rebels ‘‘could load and fire in almost perfect

safety’’ from the Union artillery fire. The initial halt to the building of the

upper bridge at 4:00 a.m. was caused by only two companies of the 17th

Mississippi, which rose from its cover to deliver a volley at the engineers.

Even after the Federals secured the crossing, they had to fight hard before

Fredericksburg was cleared of enemy troops. Barksdale’s men resisted street

by street, in one of the few instances of urban combat in the Civil War. Across

several streets they erected ‘‘considerable barricades’’ made of ‘‘barrels and

boxes, filled with earth and stones, placed between the houses, so as to form

a continuous line of defense.’’ The 19th and 20th Massachusetts crossed the

river to join the 7th Michigan. Battle lines were formed in the streets and ad-

vanced against the barricades as both sides fought at close range. William L.

Davis of the 13th Mississippi reported, ‘‘We killed lots of them in back yards

and out houses.’’ Rebel soldiers could hear Union officers urge their men

forward with shouts of ‘‘Come on’’ as they fired at muzzle flashes in the

darkness. Barksdale was only supposed to delay, not stop, the Yankees, but

Fredericksburg 159

his spirited stand lasted longer than his commander expected. He finally

gave up Fredericksburg and retired to the heights an hour after dusk.

∞≠

As Burnside’s army crossed the river on December 12, Lee’s men again

strengthened their positions. On the far left, Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox’s

Alabama brigade dug in on Taylor’s Hill. Because their position was en-

filaded by Federal guns on the opposite side of the Rappahannock, they

worked numerous angles into the line. The work had a trench and parapet

but no ditch. Each return in the line was three yards long, while the length of

each section between the returns varied. It was not the first zigzag earth-

work dug during the Civil War, as some modern commentators have as-

serted, but a cremailliere, or indented, line well established in both Euro-

pean fortification history and all the fortification manuals.

∞∞

While most Confederate guns were already fortified, Lee did not order the

infantry to dig in even though an attack on his position along the bluffs was

imminent. Lafayette McLaws’s division, however, erected works along its

part of the line in the Rebel center. Arrayed along the foot of the bluffs, the

men dug a modest infantry trench and erected breastworks through a patch

of woods with abatis in front. Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw’s South Carolina

Brigade, composing the left of McLaws’s line, built its works on the night of

December 12, finishing them by 8:00 the next morning. William L. Davis of

the 13th Mississippi claimed that Barksdale’s soldiers took it upon them-

selves to grab a few axes and erect ‘‘some fine breast-works of logs’’ in the

patch of woods. ‘‘There was no orders to do this—it was a suggestion of our

own,’’ he contended. But McLaws and Kershaw reported that their units dug

in, implying that an order was given on the division level.

∞≤

On the far right, Jackson’s Second Corps took charge of the area around

Hamilton’s Crossing on December 12. Maj. Gen. John B. Hood’s division of

Longstreet’s First Corps had held this area before and had dug a trench near

the railroad big enough to hold one and a half brigades. Hood’s men had also

cut a military road 500 yards to the rear of this work. Jackson placed four-

teen pieces of artillery just behind this little trench and used its modest

parapet as cover for the gunners. After the war, one of Jackson’s veterans

remarked that the Federals had the impression Jackson was strongly for-

tified. The truth was that none of the Corps was dug in. ‘‘We had no time to

construct anything like fortifications,’’ he later wrote. That was not truly the

reason for the lack of earthworks at Hamilton’s Crossing, for Jackson’s men

could have worked on the night of December 12. Jackson wanted to assume

the tactical offensive. He had level ground in his front and a vulnerable

position to defend, a good justification for attacking. But Lee decided this

would be purely a defensive battle and refused to unleash Jackson’s corps.

∞≥

160 Fredericksburg

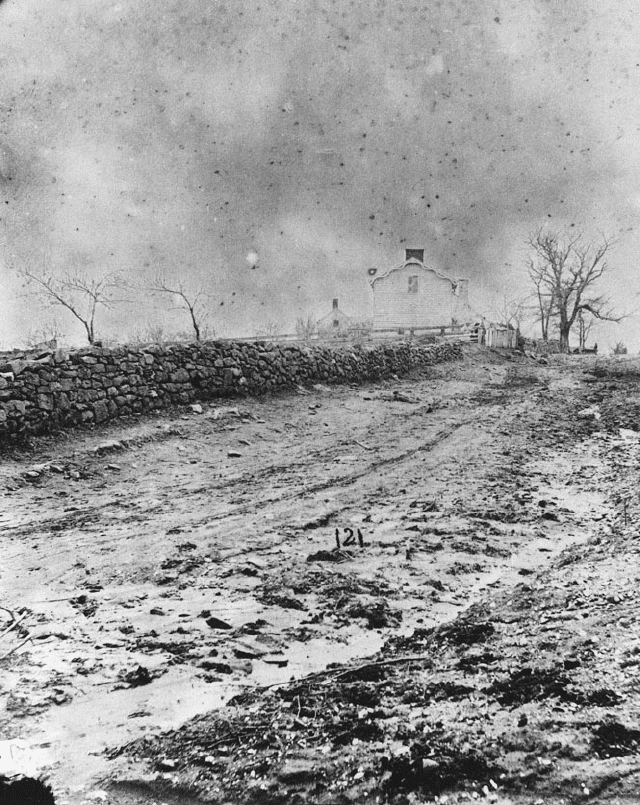

Remnants of Confederate artillery emplacements at Prospect Hill, Fredericksburg.

These emplacements were constructed by Jackson’s men just before the battle of De-

cember 13. They were improvised in a simple trench dug earlier to accommodate one

and a half brigades of infantry. (Earl J. Hess)

Thinking of Fredericksburg with postwar hindsight, Longstreet’s staff of-

ficer G. Moxley Sorrel was surprised that so few fieldworks were constructed

before the engagement. ‘‘Later in the war such a fault could not have been

found,’’ he wrote. ‘‘Experience had taught us that to win, we must fight; and

that fighting under cover was the thing to keep up the army and beat the

enemy.’’ As good as it was, Lee’s position at Fredericksburg could have been

even stronger with the addition of more earthworks.

∞∂

Jackson, especially, needed fortifications at Hamilton’s Crossing, for the

ground favored a Union attack. Franklin deployed the First and Sixth Corps

on the Union left to punch through at the crossing and turn Lee’s right.

Jackson was positioned a half-mile away on the other side of the open bot-

tomland. The only impediments were some ditches and fences that could

disrupt formations. Meade’s division of the First Corps conducted the assault

with John Gibbon’s division to its right in close support. The last division of

the First Corps was held in reserve. The entire Sixth Corps was assigned the

task of guarding the pontoon bridge, Franklin’s only lifeline to the east side of

the Rappahannock. He hoped Burnside would relieve the Sixth Corps with

troops from the army’s reserve so he could use more men in the attack, but

Fredericksburg 161

that did not happen. Nevertheless, Franklin committed a grievous error in

relying on only one division to break through Jackson’s line while assigning

an entire corps to guard a bridge. The situation called for a massive assault

with all available men.

Meade attacked at 9:00 a.m. on December 13. His men stumbled across

the obstructions posed by ditch and fence and smashed into the Rebel line

north of the artillery at Hamilton’s Crossing. The defending troops, Archer’s

Tennessee brigade, were partially covered by the small work, but the weight

of the attack forced them back. Meade penetrated an undefended marshy

area to Archer’s left, captured the crest of the low bluff to Archer’s rear, and

disrupted several other brigades; but he lost connection with Gibbon to his

right. Rebel counterattacks drove Meade back in a larger repetition of the

failed Union assaults against Jackson’s line along the unfinished railroad at

Second Manassas. Gibbon’s division hit the Rebel line a few minutes later but

was repelled. Franklin had no heart for continuing the offensive and halted

further operations on the left.

∞∑

Burnside had hoped that Franklin would draw enough Confederate

strength so that Sumner could assault Marye’s Hill, but the attack on the left

was not big or prolonged enough to achieve that goal. Nevertheless, Burn-

side sent Sumner’s men in at noon. He stated in testimony before the Joint

Committee on the Conduct of the War that the position was strong but not

well fortified, and he therefore hoped to break through immediately op-

posite the town. Aiming points to the right or left of Marye’s Hill might have

been better. Alexander believed the Federals would attack just north of the

height, while Longstreet expected an assault on McLaws’s front just to the

south. By striking the face of the hill, Burnside upset these expectations but

hit an almost impregnable section of the line.

∞∏

The Federals emerged from Fredericksburg and assembled some 300

yards from the Confederate position at the foot of Marye’s Hill. Before them

was a mostly open and gently ascending ground, cluttered here and there

with a few houses, fences, and gardens, especially at the fork of Telegraph

Road about 150 yards in front of the Rebels, but a fold of ground from one to

six feet deep offered some protection. Alexander had assembled nine guns to

bear directly on the Union line of approach, and there were eight more on

Lee’s Hill and Howison’s Hill.

∞π

The Confederate position at the foot of Marye’s Hill made good use of

existing structures. The famous stone wall was 600 yards long and held up

the eastern embankment of Telegraph Road. It was about 4 feet high in most

sections, but in others the top was even with the natural level of earth. The

road was some 25 feet wide and partly cut into the base of the hill. At its best,

162 Fredericksburg

The stone wall, Fredericksburg. A photograph taken soon after the war shows the Innis

house next to the stone wall. (Massachusetts Commandery, Military Order of the Loyal

Legion and the U.S. Army Military History Institute)

the stone wall was ‘‘just the height convenient for infantry defence and fire,’’

according to Longstreet. At its worst, the wall needed a little work. On

December 12, Confederate troops had taken dirt from behind the wall and

put it outside to make firing positions and a firmer parapet.

∞∫

The corps commander, however, admitted that no one thought it an im-

Fredericksburg 163

portant feature before the Federals attacked. McLaws claimed credit for first

suggesting troops be placed there. He had wanted to pull Barksdale’s brigade

out of Fredericksburg on the evening of December 10, a few hours before

Burnside’s engineers started to bridge the Rappahannock. McLaws was con-

vinced Barksdale would be outflanked and overwhelmed if the Federals

crossed. Longstreet wanted the Mississippi brigade to delay the Yankees as

long as possible, so he asked McLaws if there was a good defensive position

just outside town for Barksdale to fall back to. McLaws identified the sunken

road. So when Barksdale had to evacuate Fredericksburg on the night of

December 11, he retired to the stone wall. Brig. Gen. Thomas R. R. Cobb’s

brigade relieved him later that night as Barksdale’s men moved to the patch

of woods and built their breastwork the next day. Longstreet kept Cobb in

the sunken section of Telegraph Road but assumed Burnside would bypass

him and ascend Marye’s Hill.

∞Ω

The Second Corps was primarily responsible for attempting to take this

position. Maj. Gen. William H. French’s division led just after noon with

piecemeal attacks by three brigades. The first, Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball’s,

got no farther than the fork in Telegraph Road. Then Maj. Gen. Winfield S.

Hancock’s division weighed in with similar piecemeal assaults by three bri-

gades, two of which got closer than any of French’s men. Corps commander

Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch then ordered Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s divi-

sion into the fray, two brigades of which tried unsuccessfully to flank the left

of the stone wall position. When French and Hancock asked for support,

Brig. Gen. Samuel D. Sturgis’s division of the Ninth Corps sent two brigades

into action. Each attack was stopped well short of the stone wall, about 100

yards from the Rebels, although individual soldiers managed to get as close

as 30 yards.

≤≠

Cobb’s Georgia brigade was the target of this concentrated fury, and it

needed help. McLaws sent Kershaw’s South Carolina brigade from his for-

tified line to assist. Two brigades from another division—Brig. Gen. Robert

Ransom’s and Brig. Gen. John R. Cooke’s North Carolinians—also reinforced

Cobb’s line. In places, the combined manpower made a formation four ranks

deep. Kershaw’s men either knelt or stooped while waiting for the Yankees

to approach, then they rose, fired, and reloaded. Despite the heavy and

prolonged firing, no one was reported injured by their comrades in these

crowded conditions because men in the rear ranks passed loaded guns for-

ward to be fired. Some men reported firing more than 100 rounds during

the battle, and they had to stop periodically to swab out gun barrels with

pieces of their own clothing. ‘‘The boys were as black as cork minstrels’’

because of biting so many cartridges while sweating. ‘‘Our shoulders were

164 Fredericksburg

Modern view of the stone wall, Fredericksburg. This view shows the reconstructed Innis

house, the stone wall, and Telegraph Road. (Earl J. Hess)

kicked blue by the muskets and were sore for many days,’’ reported Charles

Powell of the 24th North Carolina.

≤∞

The final round of assaults took place just after 4:00 p.m., when Couch

received an erroneous report that the Rebels were evacuating the top of

Marye’s Hill. He ordered Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys’s division to

strike, and two brigades went in over the same ground where the shattered

remnants of other troops lay as mute testimony to the futility of Burnside’s

plan. Federal officers who participated in this last attack on the sunken road

later told McLaws that the Confederate fire ‘‘seemed to ‘come out of the

ground,’ and the bullets went over them in sheets.’’ The men plopped down

for safety and retired after a half-hour. Brig. Gen. George W. Getty’s divi-

sion of the Ninth Corps attacked to the north of the stone wall but made

no headway. Dusk finally ended the slaughter. The Federals used 27,000

troops to attack Marye’s Hill and lost 3,500 of them during the course of the

afternoon. Only 800 of the 3,500 Confederates who defended the stone wall

were lost.

≤≤

Burnside’s army slept on the field, but Lee ordered his elated men to

strengthen their position ‘‘by the construction of earthworks at exposed

points.’’ Exactly what was accomplished in this way is not clear, but most of

the work seems to have been done on the artillery emplacements. Alexander

Fredericksburg 165

recalled that his gunners ‘‘worked some on our pits, strengthening & repair-

ing damages’’ caused by accurate Federal shelling on December 13. Brig.

Gen. Maxcy Gregg’s South Carolina brigade of Jackson’s corps cut trees to

make a breastwork. Brig. Gen. James L. Kemper’s Virginia brigade had not

participated in the fighting that day, but it relieved Kershaw’s Carolinians in

the sunken portion of Telegraph Road. The Virginians worked all night to

raise the height of the protective wall, and by dawn they were ‘‘pretty well

hidden.’’ Barricades were erected where streets penetrated the line of the

stone wall. Lee was quite pleased with what his men had accomplished

during the night. ‘‘My army is as much stronger for their new intrenchments

as if I had received reinforcements of 20,000 men,’’ he commented the next

morning.

≤≥

Burnside considered resuming the offensive on December 14. Capt. Alan-

son M. Randol of the 1st U.S. Artillery was consulted regarding the feasibility

of knocking down the stone wall with artillery fire, but he advised against it.

Randol had found out it was a retaining wall and told the council of war that

crumbling the wall from the front would do little good as long as the sunken

road was intact. So a stalemate ensued as Couch’s men constructed defen-

sive works at the edge of town opposite Marye’s Hill. The men no longer felt

‘‘very pugnacious’’ and feared a Rebel counterstrike. The exact nature of

these defenses is unknown, but they probably consisted of breastworks made

of whatever material was handy. The scattered houses on the edge of town

also served as blockhouses for sharpshooters, and a lively exchange of skir-

mish fire was kept up all day between Couch’s men and the Rebels who con-

tinued to hold Telegraph Road. The council of war finally convinced Burn-

side to order a withdrawal, but it would not begin for twenty-four hours.

≤∂

More digging took place on December 14 as Jackson’s men extended their

meager earthwork at Prospect Hill. Entrenching tools were rushed to the

site, and railroad ties were pried loose to serve as the foundation of an

enlarged parapet. The night of December 14 was illuminated by an aurora

that helped the Rebels see as they worked. They dug an infantry trench on

top of Marye’s Hill to connect the artillery emplacements. Elsewhere on the

line, Cooke’s North Carolina brigade received tools and collected logs and

rocks to build a work with a ditch three feet deep and five feet wide. The Tar

Heels ‘‘felt ourselves quite safe for another fight.’’ Brig. Gen. James H. Lane’s

North Carolina brigade took an exposed position on the Confederate right

the next day, December 15, and the men built ‘‘a very good temporary breast-

work of logs, brush, and dirt.’’ That night the 20th North Carolina of Brig.

Gen. Alfred Iverson’s brigade, Jackson’s corps, took position on the right

wing behind the railroad embankment. Oliver E. Mercer thought the grade

166 Fredericksburg

‘‘afforded not much protection at the place that our Regt. was, so as soon as

dark we went at it with the bayonets and grabbing with our hands.’’ They

had only three spades in the regiment, so ‘‘you may believe our finger nails

were black next day.’’ The night of December 15 was dark and windy; but the

direction of the wind was west to east, and the Confederates did not hear the

noise of Burnside’s evacuation. The Army of the Potomac pulled back to the

east bank of the Rappahannock under cover of night.

≤∑

When the Rebels advanced to recover lost ground, they were amazed by

the debris of battle. The town was sacked, with many burned and looted

buildings, but most attention was drawn to the area in front of the stone

wall. The houses at the edge of town, used by the Federals as refuge and

blockhouses for three days, were filled with dead and wounded. Lots of dead

were clustered around the corners where Yankees had exchanged long-range

shots with the Confederates, but the largest concentration of bodies lay

behind a board fence that enclosed a lot filled with peach trees. Bullets

had easily passed through the boards, and Edward Porter Alexander found

enough corpses behind the fence to form ‘‘a double rank of the length of the

fence.’’ The boards were ‘‘a perfect honeycomb,’’ in the words of a Virginian

in Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s brigade. Another soldier found that he could

push every finger of his hand through a different hole at one time. There was

a sickening accumulation of blood, brains, caps, and equipment behind the

fence as well.

≤∏

During the battle of December 13, only a few units of Lee’s army were

protected by minor fortifications. Most of the artillery, Wilcox’s brigade on

Taylor’s Hill, McLaws’s three brigades in the center, Cobb’s brigade behind

the stone wall, and Archer’s brigade at Prospect Hill completed the list. But

long after Burnside recrossed the river, Lee’s army began to construct some

of the most extensive field fortifications it had yet dug in the war. Next to the

fortifications on the Warwick Line of the Peninsula campaign, and the de-

fenses of Richmond and Petersburg, the Army of Northern Virginia had

never engaged in anything like it. Whether Lee ordered it or Longstreet

initiated it on his own corps front is unclear, but soon the entire army was

engaged in fortifying the line. The effort involved clearly signaled Lee’s in-

tention of remaining on the bluff for an indefinite period of time as Burnside

mulled over his next move across the river.

≤π

All units fell to digging. Work parties were detailed, and axes, spades, and

other tools were shared. Lee had plenty of engineer officers—too many in the

opinion of Capt. James Keith Boswell, Jackson’s chief engineer. He recom-

mended that one be sent west and another be relieved, as the latter pos-

sessed no engineering experience and was afflicted with boils. Enough engi-

Fredericksburg 167

neers were left so that each division commander had one on his staff, a

unique circumstance in the Confederacy, enjoyed only by Lee’s army.

≤∫

Daniel Harvey Hill thought he could do his own engineering; conse-

quently, ‘‘no one will stay with him,’’ according to Boswell. Hill, who com-

manded a division in Jackson’s Second Corps, insisted on placing a line of

works along River Road quite close to the bank of the Rappahannock. Bos-

well inspected it and advised him to move back to the bluffs, about half a

mile to the rear. The Federals had a commanding position on the other side

of the river, and the flat land behind Hill’s advanced line would allow Federal

artillery to punish any reinforcements sent to him. Two other engineer offi-

cers agreed, but Hill stubbornly refused to move until Jackson himself inter-

vened on the side of the engineers. ‘‘So that nearly two weeks work was

thrown away on an untenable line,’’ complained Boswell.

≤Ω

Lt. William G. Williamson of the Provisional Corps of Engineers was one

of the three who advised Hill to move his line. He supervised the work done

by Hill’s division from December 29 to January 23, then spent the rest of the

month inspecting works constructed by Brig. Gen. Jubal A. Early’s division

and Brig. Gen. William B. Taliaferro’s division of the Second Corps.

≥≠

The resulting line stretched for thirty-five miles along the Rappahannock

River with a trench five feet wide and two and a half feet deep in many

places. The works ‘‘follow the contour of the ground and hug the bases of the

hills . . . , thus giving natural flanking arrangements.’’ On the far left of Lee’s

line, the works were extended upstream to United States Ford. Longstreet

wanted to stretch them even farther with a huge refused flank from there

southward so as to cross the roads leading from Chancellorsville to the rear

of Lee’s Fredericksburg position. Engineers scouted the terrain for this re-

fused section of the line, which would have been about eight miles long, and

decided where it should be laid out, but the work was never built. There

were shortages of tools and manpower. Had it been built, however, it would

have played a significant role in the Chancellorsville campaign the follow-

ing May.

≥∞

On any part of the long Confederate line there were technical and tactical

problems to work out. Jackson asked Longstreet for advice about how to

protect his men from enfilade fire. ‘‘The problem that you speak of is the one

that I was trying to solve,’’ replied Longstreet. ‘‘It occurred to me that we

might protect our men along your line of rifle trenches from the flank fire of

the batteries . . . by good traverses for that purpose, with a good traverse on

the right flank of each pit.’’ This exchange of letters has prompted many

scholars to assume Longstreet was an expert on fortifications. But historian

Edward Hagerman correctly notes that Longstreet’s solution was obvious,