Hess Earl J. Field Armies and Fortifications in the Civil War: The Eastern Campaigns, 1861-1864

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

108 From Seven Pines to the Seven Days

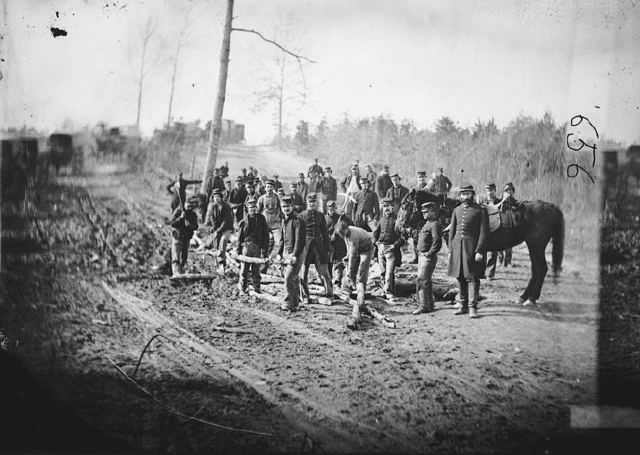

Federal engineers corduroying a road, Peninsula campaign. A rare photograph of

engineer troops engaged in road repair. Four hundred men of Brig. Gen. Daniel P.

Woodbury’s Volunteer Engineer Brigade lay corduroy along the road leading to the

railroad station at Fair Oaks and the road linking McClellan’s headquarters with that

of Brig. Gen. William F. Smith’s Sixth Corps division at Golding’s Farm on June 17–19.

Woodbury is the bearded officer on the right standing next to his horse. (Library of

Congress)

his line of communications open to Fortress Monroe and to fire on Confeder-

ate positions on the opposite bank. Batteries No. 2 and 3 were to the left and

right of the road that approached New Bridge, while No. 1 was located

farther north, near Dr. Gaines’s house. No. 4 was south of New Bridge, near

Hogan’s House. Each battery contained six guns.

In late June, Barnard authorized additional work on the Seven Pines Line.

Lt. Col. Barton S. Alexander broke ground for another artillery emplacement

big enough for thirty guns on the farm of Robert Courteny to the southwest

of Golding’s Farm. Placed between Redoubts No. 5 and 6, two regiments

worked hard enough to erect substantial cover by dawn as two other regi-

ments stood guard. Although Confederate pickets were within firing range,

the work was undisturbed. This huge concentration of ordnance was to serve

an offensive purpose, driving the Rebel artillery away from several prepared

positions in the vicinity, but it was never finished. Lee’s success in the coming

From Seven Pines to the Seven Days 109

Seven Days campaign forced Alexander to stop work on it. Only one battery

was emplaced on June 28 before the army pulled away from its advanced

position west of the Chickahominy.

∞Ω

Lee Takes Command

Neither Johnston nor Lee would rely primarily on earthworks to defend

the city. Both commanders wanted to strike at the approaching Federals and

decide the fate of the capital in open battle. The chief difference lay in the

manner of executing that strategy.

Fifty-five years old when he took command of the Army of Northern

Virginia, Lee had graduated second in the West Point class of 1829 and had

won a coveted appointment in the Corps of Engineers. He worked exten-

sively at Fort Pulaski and Fortress Monroe, performed administrative work in

Washington as assistant to the chief of the Engineer Department, and ap-

plied his talents to civil projects such as improving navigation on the Mis-

sissippi River at St. Louis. He helped to plan and build the siege works at Vera

Cruz during the Mexican War and performed superbly as a topographical

engineer throughout Winfield Scott’s advance on Mexico City.

≤≠

Lee determined on June 5, four days after assuming command of the

army, to take the offensive against McClellan. He would adopt a more bold,

comprehensive, and aggressive plan than Johnston’s. As McClellan shifted

troops across the Chickahominy River in June, he retained a sizable force

east and north of the stream. Lee wanted to attack north of the river, throw-

ing a force as heavy as that used by Johnston on a wide flanking maneuver,

while leaving the minor part of his army to block the major part of Mc-

Clellan’s force due east of Richmond.

There were two prerequisites to make this plan work. First, Lee had to

finish building the defenses of Richmond. Only by sheltering behind strong

earthworks could the comparatively small force hold off McClellan’s huge

army east of the city. Second, Lee needed all the additional help he could find.

Marginally used brigades were called northward from the coast of North

Carolina, and a small but highly successful army under Maj. Gen. Thomas J.

Jackson also had to be shifted from the Shenandoah Valley. The pressure on

the capital was so great that these theaters of secondary importance could be

depleted, for the time being, to save the heart of the Confederate nation.

Completing the Defenses of Richmond

Rives and Davis had argued earlier that any additional lines of defense

protecting the city could quickly be dug when the need arose, and now Lee

and his men set out to prove them right. Engineer officers scurried across the

110 From Seven Pines to the Seven Days

countryside laying out a forward line of defense just behind the positions

already assumed by Lee’s units following their repulse at Seven Pines. This

position would become the Outer Defense Line of Richmond. Adjustments

had to be made, but the line essentially was straight. The next step was to cut

thousands of trees that stood nearby. ‘‘Forests were felled and new roads

were made, and old ones obliterated,’’ recalled Joseph L. Brent, ‘‘so that the

entire face of the country was changed.’’ Civilians in the area moved away, if

they had not already done so, certain that the activity meant heavy fighting.

Many of their houses and outbuildings had to be burned or dismantled to

clear fields of fire. Lee rode along the developing line every day, ‘‘making

suggestions to working parties and encouraging their efforts to put sand-

banks between their persons and the enemy’s batteries,’’ recalled James

Longstreet.

≤∞

The Engineer Bureau frantically tried to supply Lee with all that he needed.

Rives dispatched a dozen engineer officers and civilian assistants, but it was

far more difficult to find proper tools. Lee clamored for shovels, picks, axes,

and spades. Rives took some axes from the navy and contracted with the

state penitentiary to make five dozen per day for the government. Regimen-

tal leaders in Lee’s army were ordered to search for any spare tools hoarded

by the men for camp chores. Rives also arranged for thousands of sandbags

to be sent to the army.

As June wore on, the need for more efficient labor by the soldiers became

paramount in order to finish the work on time. Within Rodes’s Alabama

brigade, a schedule was worked out so that each regiment, in sequence,

devoted its entire strength to the brigade’s defenses for three hours at a time.

When Walter H. Stevens, who was in charge of the defenses, asked Rives for

300 black laborers, the bureaucrat could not supply them. The numerous

shortages led Stevens to complain about inefficiency at the Engineer Bureau.

Rives explained to Lee that he could not personally compensate for the

Confederacy’s lack of resources. ‘‘In addition to my other duties,’’ he con-

fessed, ‘‘I find my position of general supply & disbursing agent for Major

Stevens exceedingly onerous.’’

≤≤

Yet the works took shape despite tool shortages and ruffled feathers.

Supervision of the digging fell to infantry officers, most of whom were un-

tutored in the art of fortification. Brig. Gen. William Dorsey Pender, com-

mander of a North Carolina brigade in Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill’s division, wanted

the works to be as uniform as possible. He sought ‘‘to make them look pretty I

suppose,’’ commented John Wetmore Hinsdale, his staff officer. Hinsdale

knew that it would be more effective to curve the line to take advantage of

each undulation in the land, and he also knew that it was important to cut

From Seven Pines to the Seven Days 111

down all the trees immediately in front of the trench. Yet Pender wanted to

keep many trees intact to serve as forward observation posts. When Hinsdale

offered his advice, Pender assured him he ‘‘knew all about it,’’ so Hinsdale

kept quiet and concluded that his leader was a conceited fool. It was a harsh

judgment, for Pender would soon prove his ability as an aggressive bat-

tlefield commander.

≤≥

After the war, several Confederate officers argued that the rank and file

enthusiastically supported Lee’s plan to dig in around Richmond. Joseph

Brent remembered that the men were shocked by the casualties suffered at

Seven Pines. They had come to ‘‘appreciate the advantages of entrenched

position, and their approval of Gen. Lee’s policy was very cordial.’’ Long-

street also claimed that the men had started to know the value of earth-

works. But contemporary evidence seems to indicate that the opposite was

true. The soldiers apparently complained loudly about the hard work, believ-

ing that attack was the only way to save Richmond. Their initial view of Lee

was decidedly uncomplimentary. Noting his relatively advanced age, they

called him ‘‘Granny Lee’’ or the ‘‘King of Spades.’’

≤∂

Lt. Robert G. Haile of the 55th Virginia, in Brig. Gen. Charles W. Field’s

brigade of Hill’s division, apparently spoke for many soldiers when he ex-

pressed disgust at the digging. Haile could see the Federals constructing

earthworks across a stream in front of his regiment. ‘‘That is the system that

they are going to persue,’’ he concluded, to hold every inch of ground they

could. ‘‘I don’t think it should be allowed[.] I go for attacking them at once

and never stop untill they are driven from our soil. The very idea of two large

armys only separated by a small stream to be entrenching themselves is out

of the question. I go in for their meeting each other in open ground and fight

it out and be done with it.’’

≤∑

Civilian observers also castigated Lee for his policy. John M. Daniel, editor

of the Richmond Examiner, spared no vitriol in denouncing Lee as incompe-

tent. West Pointers knew only how to dig, to fight the war on ‘‘scientific’’

principles, and lacked the visceral need to destroy their enemy. Daniel wrote

out of frustration; after Johnston’s dilatory strategy and failed attack at

Seven Pines, the citizens of Richmond were understandably worried and

hoping for a savior. At first, Lee did not seem to fit the bill.

≤∏

While outwardly unfazed by the criticism, Lee took quiet notice of it and

made haste to defend himself. McClellan would dig his way into the city,

Lee warned Jefferson Davis, by taking and fortifying position after position

under cover of his heavy guns. Lacking the same weight and quantity of

ordnance, the Confederates could only win by storming his works. Waiting

on the defensive to resist a siege would only prolong the campaign, not

112 From Seven Pines to the Seven Days

change its outcome. Davis understood that Lee wanted to build works so he

could hold the city with minimal manpower while using the rest for offensive

action, but Lee wanted to make sure the president would support this policy

in the face of widespread criticism. ‘‘Our people are opposed to work,’’ Lee

complained. Officers, soldiers, and civilians alike ridiculed it as unnecessary.

Yet work was ‘‘the very means by which McClellan has and is advancing. Why

should we leave to him the whole advantage of labor[?] Combined with

valour fortitude & boldness, of which we have our fair proportion, it should

lead us to success.’’

≤π

Within a month of taking command, Lee had the defenses of Richmond

ready to serve his strategic needs. As they were improved over the course of

the war, the works became an impressive system of fortifications.

The Inner Line consisted of sixteen detached redoubts about one mile

from the edge of the city. Twelve works lay north of the James, stretching all

the way from the eastern to the western side and anchored on the river. Four

redoubts lay south of the James. The works were open to the rear, but their

outline often was complex, incorporating several bastions. In fact, many

people today refer to them as ‘‘star forts’’ because of their pointy appearance

on maps.

The Intermediate Line was a continuous line of works from one and a half

to three miles from the edge of the city. It also stretched from one side of

Richmond to the other, anchored on the James. A forward extension of the

line ran to the Outer Line north of the city, forming a short corridor con-

necting the two lines at this point and protecting the Mechanicsville Pike and

the Virginia Central Railroad. The Intermediate Line stretched south of the

James, covering about half the southern approach to the city.

The Outer Line was the one most heavily dug by Lee’s men in June 1862.

It started at Chaffin’s Bluff and extended northward to the Chickahominy

River at New Bridge, five miles northeast of the city’s edge, and covered the

eastern approaches to Richmond. This stretch was a continuous line. Then a

line of detached works ran along the south bank of the Chickahominy from

New Bridge for nearly four miles to the Chickahominy Bluffs due north of

town. This part of the line was continuous for about one and a half miles, and

here also was the extension connecting the Outer and Intermediate Lines.

From this point, the line ran continuously another mile to the junction of

Brook Run and the Chickahominy. The run flowed west to east into the river,

due north and four miles from the city’s edge. From this junction, there was a

line of detached works for six miles along the south bank of Brook Run, be-

fore the line angled southward to end at the James River west of Richmond.

This represented an enormous amount of digging. The Inner Line ran for

From Seven Pines to the Seven Days 113

eight miles, the Intermediate Line stretched for fourteen miles, and the

Outer Line totaled some twenty-six miles. A more efficiently planned system

could have reduced this labor significantly, for the Outer Line was the most

important, while the Intermediate Line was, arguably, necessary as a fall-

back position. The Confederates were lucky to have come up with enough

ideas, labor, guns, spades, and strong backs to construct a workable, al-

though redundant, system of defense for the capital.

≤∫

The Outer Line was anchored at Chaffin’s Bluff, a fifty-foot-high eminence

on the north bank of the James River one and a half miles downstream from

Drewry’s Bluff. The construction of river batteries had already been started

by May 16. Eight heavy guns were in place by the time Johnston attacked at

Seven Pines, but there were still no works for either infantry or field artillery

by the time Lee started the Outer Line. The new commander ordered the

additional work at Chaffin’s immediately, and a feverish pace of activity was

begun that would extend well beyond the immediate campaign.

Engineer Lt. William Elzey Harrison laid out the works, while Henry A.

Wise’s Virginia brigade provided most of the labor, with help from a force of

black workers. Harrison’s line began near the bluff and crossed Osborne

Pike, one of several good roads leading to the southeast sector of Richmond.

It angled to take advantage of a ridge up to 140 feet tall. The first segment of

the line was made up of five detached batteries and stretched to a private

house called Mountcastle. From there the line consisted of an infantry trench

studded with ten more batteries. The whole line stretched for a mile and a

half and crossed two other approaches to Richmond. Battery No. 11 covered

the Varina Road, and Batteries No. 12, 13, 14, and 15 covered New Market

Road. They were completed by early August 1862 despite a break by Wise’s

men to take part in the battle of Malvern Hill. This line would be heavily

strengthened, and many additional works would be added in the vicinity to

better protect the river batteries at Chaffin’s Bluff. Batteries No. 7, 8, and 9

would later be transformed into Fort Harrison, a key target of the Federal

Fifth Offensive of September 1864 during the Petersburg campaign.

≤Ω

The only remnants of Richmond’s defenses are a few bits and pieces of the

Outer Line. East of Richmond and a few hundred yards south of Williams-

burg Road, the line was straight and consisted of a large parapet fronted by a

deep ditch. There was no trench or traverses along the infantry curtain, but

several two-gun emplacements were made with raised platforms. A traverse

separated the two emplacements within each bastion. North of Richmond,

along the Chickahominy Bluffs, a more complex and stronger artillery posi-

tion was constructed just east of Mechanicsville Pike. Three two-gun em-

placements were made with protecting traverses and parapets, the latter

114 From Seven Pines to the Seven Days

thickened by digging a ditch in front. A trench was dug along the connecting

infantry line, which was curved to conform to the edge of the bluff. The

infantry parapet was only half as large as the traverses that protected the

artillery. The crossing of the river along Mechanicsville Pike was long and

vulnerable, hence the fairly elaborate earthworks. The road stretched along

a causeway over the wide, swampy bottomland. The bluffs are about 100 feet

above the river level.

An artillery emplacement on the south bank of Brook Run, five miles

north of the state capitol and just west of Brook Road, overlooked the wide,

gently sloping ground to the stream. It stands about fifty feet above the brook

level. This was a historic spot, the rendezvous point for Gabriel’s Conspiracy,

an abortive slave uprising in 1800. Gabriel, from nearby Brookfield Planta-

tion, planned to gather hundreds of fellow slaves here, attack Richmond,

capture Governor James Monroe, and seize arms at the state arsenal. The

plot fell apart when a storm flooded Brook Run and two plotters revealed the

scheme to their masters. Gabriel and more than thirty followers were ex-

ecuted. The spot also was the scene of three separate cavalry attacks on Rich-

mond later in the war. Maj. Gen. George Stoneman’s Federals skirmished

here on the night of May 4, 1863, and Brig. Gen. Hugh Judson Kilpatrick

captured the artillery emplacement on March 1, 1864, with 3,500 troopers.

He shelled the Intermediate Line for a while before retreating. Finally, Maj.

Gen. Philip Sheridan’s 12,000 troopers unsuccessfully attacked the position

on May 11, 1864, hours after winning the battle of Yellow Tavern and mor-

tally wounding Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart two miles north of here.

The works at this spot were quite strong; their capture by Kilpatrick was

merely the result of a surprise. The massive artillery position has three gun

emplacements, two on the natural level of the earth and the third on a

sunken platform. Each platform has a large traverse to its left, an embrasure

to its front, and a ditch in front of the large parapet. A stretch of remaining

infantry line to the east side of Brook Road shows that the Outer Line also

was massive. There was no trench, but the line consisted of a large parapet

and a deep and wide ditch.

≥≠

The Outer Line would be the primary defense of Richmond for the rest of

the war, yet it might not have been built at all except for Lee’s decision to

entrench in June 1862. Unlike Washington, the Confederate capital was pri-

marily shielded by a line that was initiated for the purpose of making an

offensive against the enemy more certain of success. In both cases the earth-

works freed the defending armies and gave them the flexibility to strike at

the enemy. In the case of the Federals, that meant a four-year series of

From Seven Pines to the Seven Days 115

N

N

N

Chickahominy Bluffs, east of

Mechanicsville Pike,

north of Richmond

Ditch in front

of artillery

emplacements

Twenty-yard gap

Borrow

pits

Three-gun emplacement on

Outer Line, immediately

west of Brook

Turnpike, north of Richmond

Two-gun emplacement on

Outer Line, south of

Williamsburg Road,

east of Richmond

E

d

g

e

o

f

B

l

u

f

f

M

e

c

h

a

n

i

c

s

v

i

l

l

e

P

i

k

e

Richmond Defenses, Spring 1862 (based on field visits, 1994 and 1997)

campaigns to take Richmond; in the case of the Confederates, it meant the

much more limited goal of driving the enemy from the gates of the capital in

the summer of 1862. Both systems of defense served their purposes well until

Grant’s relentless drive to Richmond forced Lee to shelter his army in the

works and adopt a strategy that Lee and Davis had always feared would

result in the eventual loss of the city.

116 From Seven Pines to the Seven Days

Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Besides completing the defenses of Richmond, the Confederates had to

bring Jackson’s army from the Shenandoah Valley in preparation for Lee’s

Seven Days campaign. Jackson had already created a name for himself at

First Manassas, but his claim to military genius was established by a short,

brilliant campaign in the Valley of Virginia that tied down more than 50,000

Federal troops while using 15,000 of his own. Jackson took advantage of the

good roads and generally level landscape of the valley and employed a Napo-

leonic strategy of maneuver between three widely separated columns of

Union soldiers. He had the advantage of interior lines of march and good

troops. It was a combination that baffled the Yankees for weeks and led

Lincoln to refuse McClellan’s persistent calls for more men in favor of de-

fending the capital against a possible strike by the Confederates.

≥∞

Jackson, a graduate of the West Point class of 1846, had gone immediately

to war in Mexico. Commissioned into the artillery, he had participated in the

siege of Vera Cruz and in many other actions throughout Scott’s campaign

to Mexico City. Jackson was exposed to the use of fortifications but never

seemed to have developed a special knowledge of them. His attitude toward

operations, fully developed in the Valley campaign of 1862, emphasized ma-

neuver and open field fighting to attain his strategic goals. Jackson seems to

have disdained fortifications either for offense or defense, for they hardly

played a role in the campaign. His Federal opponents, still inexperienced in

operations, also paid scant attention to them.

≥≤

The landscape of the region, as already noted, well suited Jackson’s needs.

The Shenandoah Valley, on the margin between the Piedmont and the Appa-

lachian Highlands, is one of Virginia’s unique geographic features. The east-

ern extent of the highlands is the western boundary of the valley. The lower

part of the valley is so wide that the bordering mountains are out of sight. The

valley slowly narrows as one proceeds upriver, to the southwest, and ends

near Lexington, 160 miles from Harpers Ferry, where the Shenandoah emp-

ties into the Potomac River. West of the Valley, however, one enters a true

Appalachian landscape, with high, dominating ridges stretching from the

northeast to the southwest, rugged and often narrow valleys between, and

jumbled mountains stretching west as far as the eye can see.

≥≥

The Federals had already conquered much of this mountainous western

side of Virginia but were as yet quiet in their occupation duties some fifty

miles west of the Valley. Jackson initiated operations in the Shenandoah in

March 1862, when he attacked another occupying force at Winchester, in the

wide, lower end of the Valley. The resulting battle of Kernstown, fought just

outside Winchester on March 23, was a Confederate failure. Jackson’s men

From Seven Pines to the Seven Days 117

were repulsed in open field fighting, some of which swirled around a stone

fence on the end of a dominating ridge outside Kernstown. It was one of the

few battlefield defeats that Jackson suffered during the war, yet the Valley

remained quiet for more than a month as McClellan launched his drive up

the Peninsula.

≥∂

By early May, when the Army of the Potomac was beginning to close in on

Richmond, the need to divert Yankee attention had become paramount.

Jackson initially moved against a force under Brig. Gen. Robert H. Milroy

that was advancing eastward across the Appalachian Highlands. Milroy had

rested in winter quarters ever since his failed attack on the Confederate

garrison of Camp Alleghany in December 1861. By the early spring, Southern

commanders had given up hope of retaining the western mountains of Vir-

ginia, and Brig. Gen. Edward Johnson evacuated Camp Alleghany in early

April. Milroy immediately moved forward to occupy it. ‘‘I was greatly sur-

prised at the great extent and immense strength of the reble fortifications

and winter quarters here,’’ he informed his wife. Most of the existing works

had been built following his attack. ‘‘The place is now almost a Gibralter for

strength both by nature and art.’’ Fortunately for Milroy’s men, the Confeder-

ates left their forage, winter huts, and stables intact; a heavy snowstorm hit

the mountaintop on April 7, the day after the Federals occupied the camp.

≥∑

Milroy pursued Johnson on April 8, advancing along the Staunton-

Parkersburg Turnpike, one of two major avenues of invasion into the moun-

tains of western Virginia. He hoped to push all the way to Staunton in

the middle part of the Shenandoah Valley, completing the nine-month se-

ries of moves along that mountain road, but Johnson began to fortify on

top of Shenandoah Mountain. The pike crawled across this rugged barrier,

which was twenty-six miles from Camp Alleghany and twenty-two miles from

Staunton. Like many features named ‘‘mountains’’ in Appalachia, this land-

form is really a huge ridge that stretches for dozens of miles. Where the road

crosses the ridge through a narrow and shallow gap, Johnson’s men built a

fortified camp named Fort Edward Johnson. Like most fortified posts in the

Appalachians, it was a superb defensive position unassailable by frontal

approach but vulnerable to a flanking movement. The works are well pre-

served. North of the pike, they consist of a thin infantry parapet that con-

forms to the edge of the narrow ridgetop. A one-gun emplacement is located

400 yards north of and 100 feet higher in elevation than the pass. A similar

parapet lies south of the pike, but there are no artillery emplacements. Nei-

ther work has a traverse or a ditch. The Confederates were lucky to have

scratched even a modest parapet and trench from the rocky soil. But the

dominating view for thirty miles in all directions and the nearly vertical sides