Heiman G. Basic Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

378 CHAPTER 15 / Chi Square and Other Nonparametric Procedures

■ ■ ■ SUMMARY OF

FORMULAS

1. The formula for chi square is

In a one-way chi square:

In a two-way chi square:

df 5 1Number of rows 2 121Number of columns 2 12

f

e

5

1Cell’s row total f

o

21Cell’s column total f

o

2

N

df 5 k 2 1

2

obt

5 © a

1f

o

2 f

e

2

2

f

e

b

2. The formula for the phi coefficient is

3. The formula for the contingency coefficient is

C 5

B

2

obt

N 1

2

obt

1C2

5

B

2

obt

N

Additional Statistical Formulas

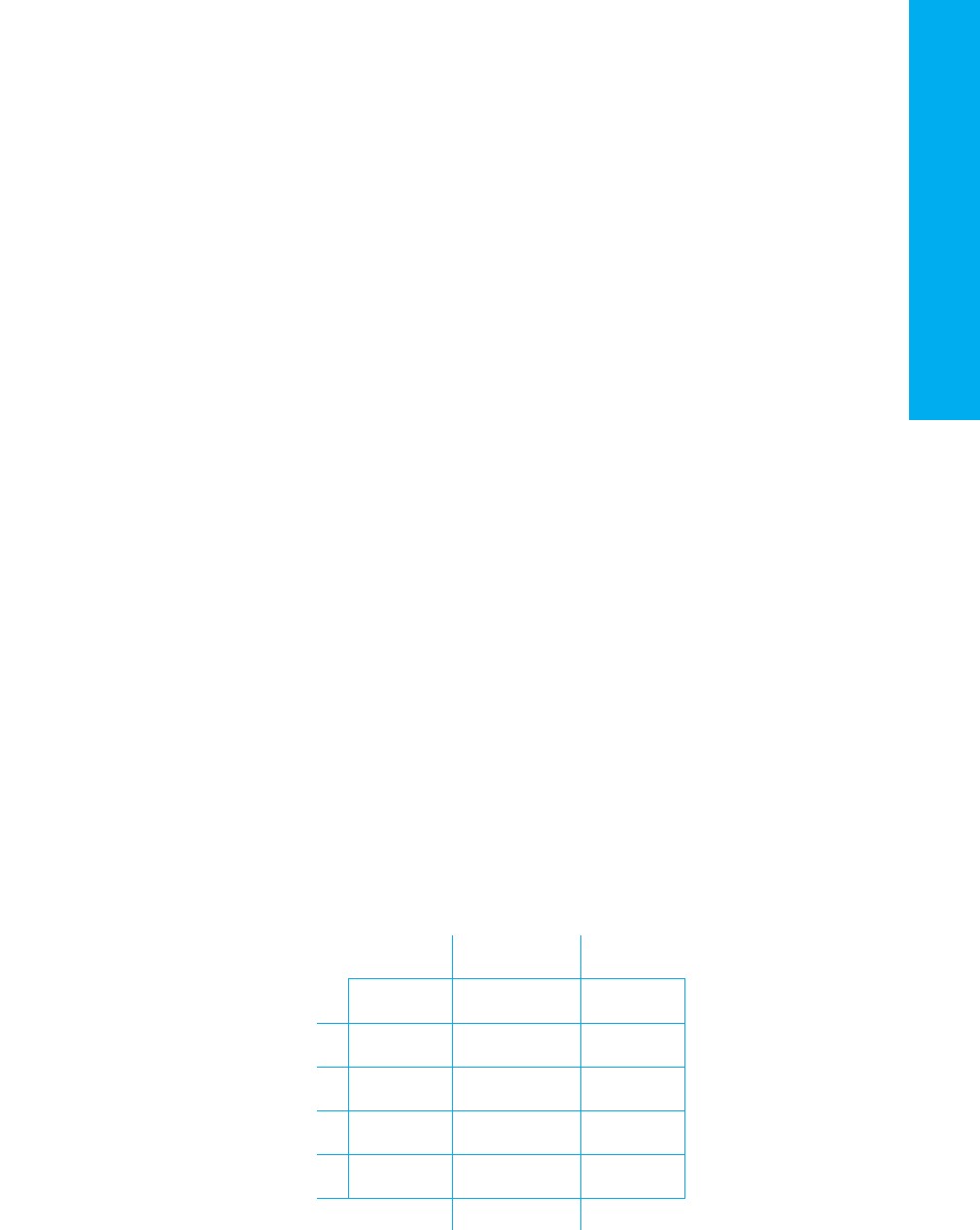

A.1 CREATING GROUPED FREQUENCY DISTRIBUTIONS

In a grouped distribution, different scores are grouped together, and then the total

of each group is reported. For example, say that we measured the level of

anxiety exhibited by 25 participants, obtaining the following scores:

First, determine the number of scores the data span. The number spanned between

any two scores is

Thus, there is a span of 39 values between 41 and 3.

Next, decide how many scores to put into each group, with the same range of scores

in each. You can operate as if the sample contained a wider range of scores than is actu-

ally in the data. For example, we’ll operate as if these scores are from 0 to 44, spanning

45 scores. This allows nine groups, each spanning 5 scores, resulting in the grouped

distribution shown in Table A.1.

The group labeled 0–4 contains the scores 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4, the group 5–9 contains

5 through 9, and so on. Each group is called a class interval, and the number of scores

spanned by an interval is called the interval size. Here, the interval size is 5, so each

group includes five scores. Choose an interval size that is easy to work

with (such as 2, 5, 10, or 20). Also, an interval size that is an odd num-

ber is preferable because later we’ll use the middle score of the interval.

Notice several things about the score column in Table A.1. First, each

interval is labeled with the low score on the left. Second, the low score

in each interval is a whole-number multiple of the interval size of 5.

Third, every class interval is the same size. (Even though the highest

score in the data is only 41, we have the complete interval of 40–44.)

Finally, the intervals are arranged so that higher scores are located

toward the top of the column.

To complete the table, find the for each class interval by summing the

individual frequencies of all scores in the group. In the example, there

are no scores of 0, 1, or 2, but there are two 3s and five 4s. Thus, the 0–4

interval has a total of 7. For the 5–9 interval, there are two 5s, one 6, no

7s, one 8, and no 9s, so is 4. And so on.f

f

f

Number of scores 5 1High score 2 Low score21 1

3 4418 428

18223171226

2641540 4 65

4208153836

f, rel. f, or cf

A.1 Creating Grouped Frequency Distributions

A.2 Performing Linear Interpolation

A.3 The One-Way, Within-Subjects Analysis of Variance

379

ADDITIONAL STATISTICAL FORMULAS

A

The column on the left identifies the lowest

and highest score in each class interval.

Anxiety

Scores f rel. f cf

40–44 2 .08 25

35–39 2 .08 23

30–34 0 .00 21

25–29 3 .12 21

20–24 2 .08 18

15–19 4 .16 16

10–14 1 .04 12

5– 9 4 .16 11

0– 4 7 .28 7

㛬㛬㛬 㛬㛬㛬㛬

Total: 25 1.00

TABLE A.1

Grouped Distribution

Showing f, rel. f, and cf

for Each Group of

Anxiety Scores

Compute the relative frequency for each interval by dividing the for the interval

by . Remember, is the total number of raw scores (here, 25), not the number of class

intervals. Thus, for the 0–4 interval, equals 7/25, or .28.

Compute the cumulative frequency for each interval by counting the number of

scores that are at or below the highest score in the interval. Begin with the lowest inter-

val. There are 7 scores at 4 or below, so the for interval 0–4 is 7. Next, is 4 for the

scores between 5 and 9, and adding the 7 scores below the interval produces a of 11

for the interval 5–9. And so on.

Real versus Apparent Limits

What if one of the scores in the above example were 4.6? This score seems too large for

the 0–4 interval, but too small for the 5–9 interval. To allow for such scores, we consider

the “real limits” of each interval. These are different from the upper and lower numbers of

each interval seen in the frequency table, which are called the apparent upper limit and the

apparent lower limit, respectively. As in Table A.2, the apparent limits for each interval

imply corresponding real limits. Thus, for example, the interval having the apparent limits

of 40–44 actually contains any score between the real limits of 39.5 and 44.5.

Note that (1) each real limit is halfway between the lower apparent limit of one inter-

val and the upper apparent limit of the interval below it, and (2) the lower real limit of

one interval is always the same number as the upper real limit of the interval below it.

Thus, 4.5 is halfway between 4 and 5, so 4.5 is the lower real limit of the 5–9 interval

and the upper real limit of the 0–4 interval. Also, the difference between the lower real

limit and the upper real limit equals the interval size .

Real limits eliminate the gaps between intervals, so now a score such as 4.6 falls into

the interval 5–9 because it falls between 4.5 and 9.5. If scores equal a real limit (such

as two scores of 4.5), put half in the lower interval and half in the upper interval. If one

score is left over, just pick an interval.

The principle of real limits also applies to ungrouped data. Implicitly, each individ-

ual score is a class interval with an interval size of 1. Thus, when a score in an

ungrouped distribution is labeled 6, this is both the upper and the lower apparent lim-

its. However, the lower real limit for this interval is 5.5, and the upper real limit is 6.5.

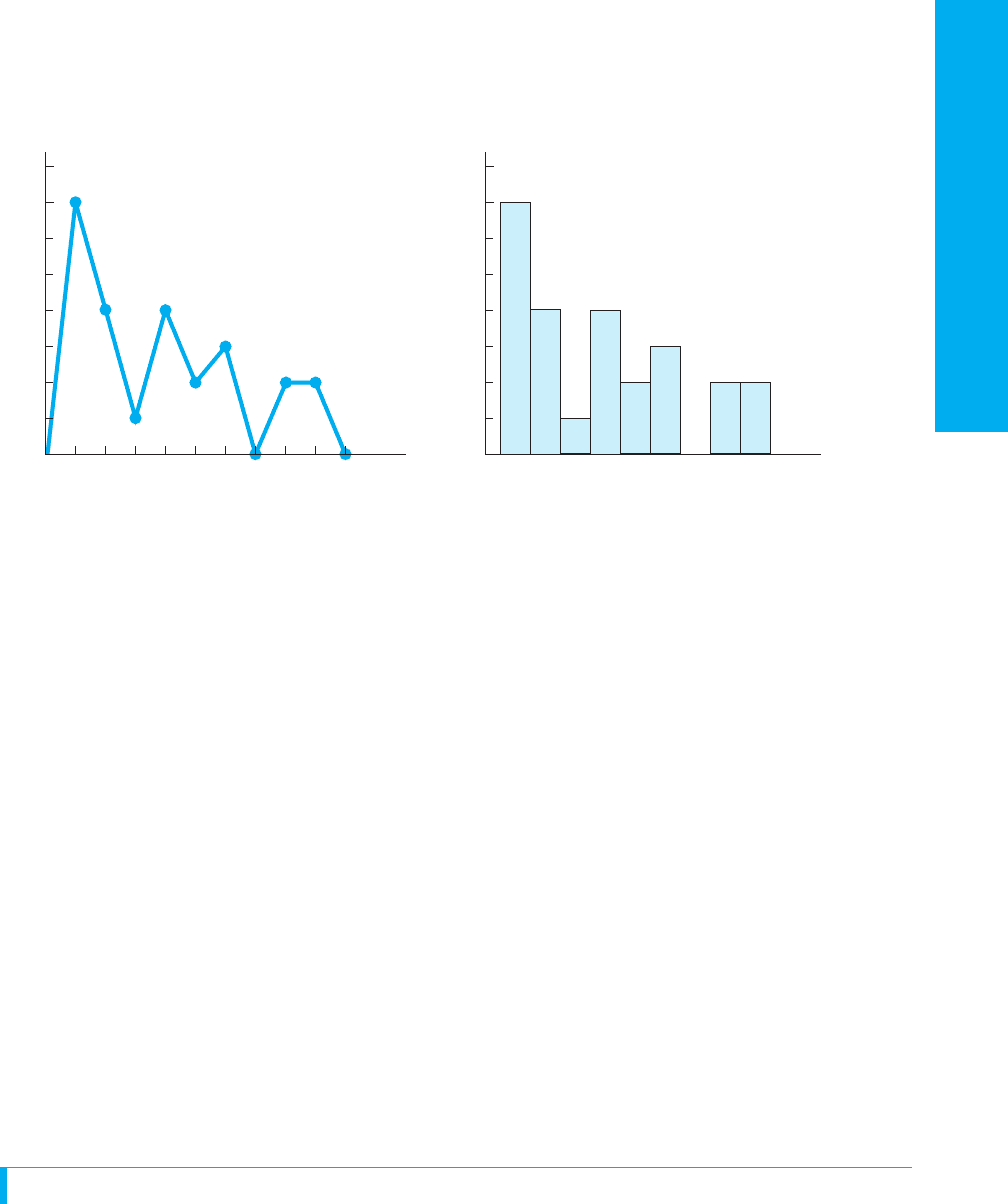

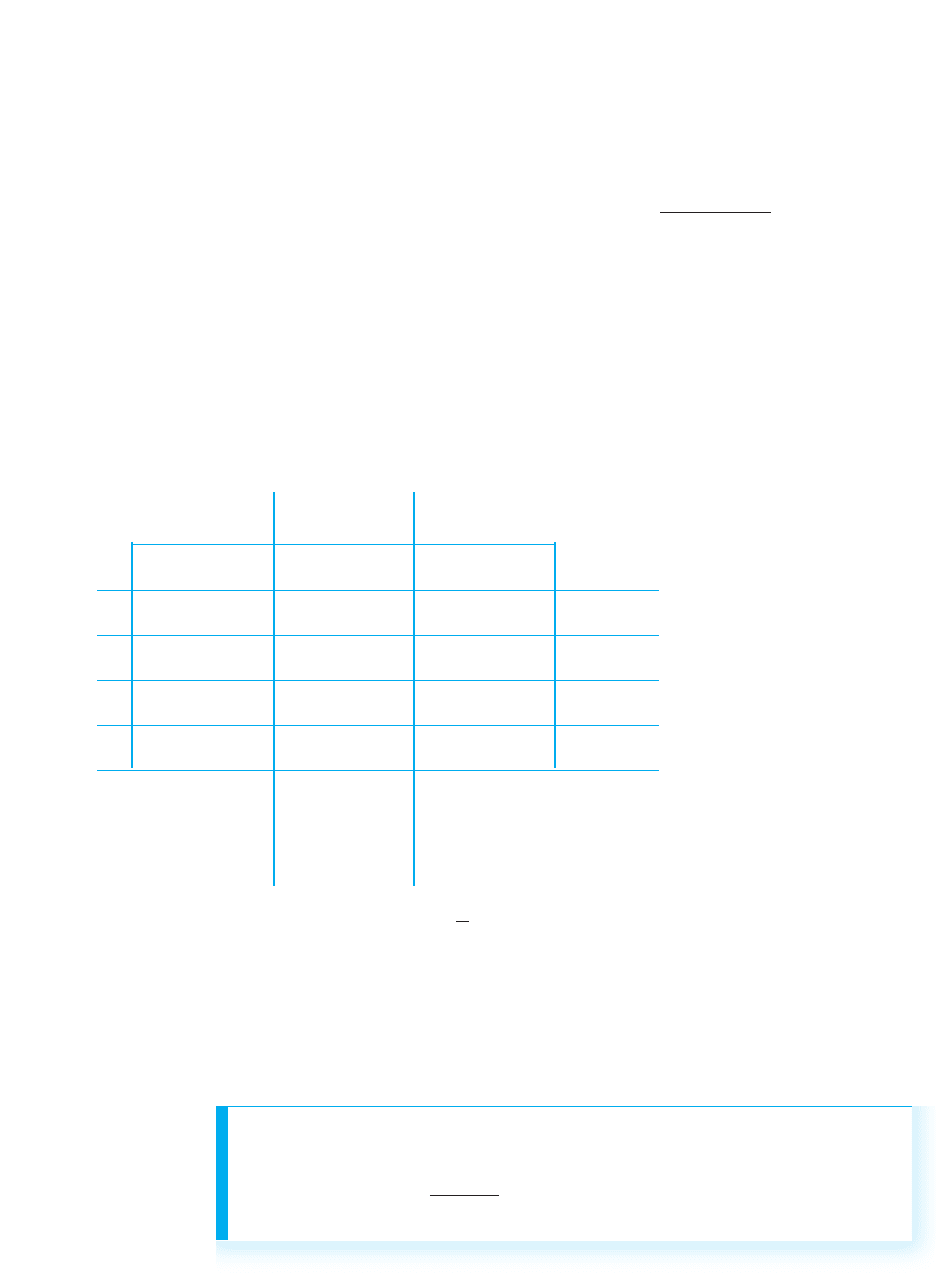

Graphing Grouped Distributions

Grouped distributions are graphed in the same way as ungrouped distributions, except

that the X axis is labeled differently. To graph simple frequency or relative frequency,

label the X axis using the midpoint of each class interval. To find the

midpoint, multiply times the interval size and add the result to the

lower real limit. Above, the interval size is 5, which multiplied

times is 2.5. For the 0–4 interval, the lower real limit is .

Adding 2.5 to yields 2. Thus, the score of 2 on the X axis iden-

tifies the class interval of 0–4. Similarly, for the 5–9 interval, 2.5

plus 4.5 is 7, so this interval is identified using 7.

As usual, for nominal or ordinal scores create a bar graph,

and for interval or ratio scores, create a histogram or polygon.

Figure A.1 presents a histogram and polygon for the grouped

distribution from Table A.1. The height of each data point or bar

corresponds to the total simple frequency of all scores in the class

interval. Plot a relative frequency distribution in the same way,

except that the Y axis is labeled in increments between 0 and 1.

2.5

2.5.5

.5

19.5 2 4.5 5 52

cf

fcf

rel. f

NN

f

380 APPENDIX A / Additional Statistical Formulas

The apparent limits in the column on the left

imply the real limits in the column on the right.

Apparent Limits Real Limits

(Lower–Upper) Imply (Lower–Upper)

40–44 → 39.5–44.5

35–39 → 34.5–39.5

30–34 → 29.5–34.5

25–29 → 24.5–29.5

20–24 → 19.5–24.5

15–19 → 14.5–19.5

10–14 → 9.5–14.5

5– 9 → 4.5– 9.5

0– 4 → ⫺0.5– 4.5

TABLE A.2

Real and Apparent Limits

Application Questions

(Answers for odd-numbered questions are in Appendix D.)

1. Organize the scores below into an ungrouped distribution showing simple

frequency, cumulative frequency, and relative frequency.

49 52 47 52 52 47 49 47 50

51 50 49 50 50 50 53 51 49

2. Using an interval size of 5, group these scores and construct a table that shows sim-

ple, relative, and cumulative frequency. The highest apparent limit is 95.

76 66 80 82 76 80 84 86 80 86

85 87 74 90 92 87 91 94 94 91

94 93 57 82 76 76 82 90 87 91

66 80 57 66 74 76 80 84 94 66

3. Using an interval size of 4, group these scores and construct a table showing

simple, relative, and cumulative frequency. The lowest apparent limit is 100.

122 117 116 114 110 109 107

105 103 102 129 126 123 123

122 122 119 118 117 112 108

117 117 126 123 118 113 112

A.2 PERFORMING LINEAR INTERPOLATION

This section presents the procedures for linear interpolation of z-scores as discussed in

Chapter 6 and of values of as discussed in Chapter 11.t

crit

A.2 Performing Linear Interpolation 381

ADDITIONAL STATISTICAL FORMULAS

0

Anxiety scores

(midpoints of class intervals)

Anxiety scores

(midpoints of class intervals)

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

f

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

f

Histogram

Polygon

2 7 12 17 22 27 32 37 42 47 0 2 7 12 17 22 27 32 37 42

FIGURE A.1

Grouped frequency polygon and histogram

Interpolating from the z-Tables

You interpolate to find an exact proportion not shown in the z-table or when dealing with

a z-score that has three decimal places. Carry all computations to four decimal places.

Finding an Unknown z-Score

Say that we seek a z-score that corresponds to exactly of the curve between

the mean and z. First, from the z-tables, identify the two bracketing proportions that are

above and below the target proportion. Note their corresponding z-scores. For ,

the bracketing proportions are at and at . Arrange

the values this way:

Known Unknown

Proportion under Curve z-score

Upper bracket .4505 1.6500

Target .4500 ?

Lower bracket .4495 1.6400

Because the “known” target proportion is bracketed by and , the

“unknown” target z-score falls between 1.6500 and 1.6400.

First, deal with the known side. The target of is halfway between and

. That is, the difference between the lower known proportion and the target

proportion is one-half of the difference between the two known proportions. We

assume that the z-score corresponding to is also halfway between the two

bracketing z-scores of 1.6400 and 1.6500. The difference between these z-scores is

, and one-half of that is . To go to halfway between 1.6400 and 1.6500, we

add to 1.6400. Thus, a z-score of 1.6450 corresponds to of the curve

between the mean and .

The answer will not always be as obvious as in this example, so use the following

steps.

Step 1 Determine the difference between the upper and lower known brackets. In the

example . This is the total distance between the two proportions.

Step 2 Determine the difference between the known target and the lower known

bracket. Above, .

Step 3 Form a fraction with the answer from Step 2 as the numerator and the answer

from Step 1 as the denominator. Above, the fraction is . Thus,

is one-half of the distance from to .

Step 4 Find the difference between the two brackets in the unknown column. Above,

. This is the total distance between the two z-scores that

bracket the unknown target z-score.

Step 5 Multiply the answer in Step 3 by the answer in Step 4. Above, .

The unknown target z-score is larger than the lower bracketing z-score.

Step 6 Add the answer in Step 5 to the lower bracketing z-score. Above,

. Thus, of the normal curve lies between

the mean and .z 5 1.645

.45001.640 5 1.645.005 1 1.640 5 1.645

.005

1.521.01025 .005

1.6500 2 1.6400 5 .010

.4505.4495

.4500.0005>.0010 5 .5

.4500 2 .4495 5 .0005

.4505 2 .4495 5 .0010

z

.4500.005

.005.010

.4500

.4505

.4495.4500

.4495.4505

z 5 1.6400.4495z 5 1.6500.4505

.4500

.45 1.45002

382 APPENDIX A / Additional Statistical Formulas

Finding an Unknown Proportion

Apply the above steps to find an unknown proportion for a known three-decimal

z-score. For example, say that we seek the proportion between the mean and a z of

1.382. From the z-tables, the upper and lower brackets around this z are 1.390 and

1.380. Arrange the z-scores and corresponding proportions as shown below:

Known Unknown

z-score Proportion under Curve

Upper bracket 1.390 .4177

Target 1.382 ?

Lower bracket 1.380 .4162

To find the target proportion, use the preceding steps.

Step 1

This is the total difference between the known bracketing z-scores.

Step 2

This is the distance between the lower known bracketing z-score and the target z-score.

Step 3

This is the proportion of the distance that the target z-score lies from the lower bracket.

A of 1.382 is of the distance between 1.380 and 1.390.

Step 4

The total distance between the brackets of and in the unknown column is

.

Step 5

Thus, of the distance separating the bracketing proportions in the unknown column

is .

Step 6

Increasing the lower proportion in the unknown column by takes us to the point

corresponding to of the distance between the bracketing proportions. This point is

, which is the proportion that corresponds to .

Interpolating Critical Values

Sometimes you must interpolate between the critical values in a table. Apply the same

steps described above, except now use degrees of freedom and critical values.

For example, say that we seek the corresponding to 35 (with , two-

tailed test). The -tables have values only for 30 and 40 , giving the following:

Known Unknown

df Critical Value

Upper bracket 30 2.042

Target 35 ?

Lower bracket 40 2.021

dfdft

␣ 5 .05dft

crit

z 5 1.382.4165

.20

.0003

.4162 1 .0003 5 .4165

.0003

.20

10.20210.001525 .0003

.0015

.4162.4177

.4177 2 .4162 5 .0015

.20z

.002

.010

5 .20

1.382 2 1.380 5 .002

1.390 2 1.380 5 .010

A.2 Performing Linear Interpolation 383

ADDITIONAL STATISTICAL FORMULAS

Because 35 is halfway between 30 and 40 , the corresponding critical value is

halfway between 2.042 and 2.021. Following the steps described for z-scores, we have

Step 1

This is the total distance between the known bracketing .

Step 2

Notice a change here: This is the distance between the upper bracketing and the

target .

Step 3

This is the proportion of the distance that the target lies from the upper known

bracket. Thus, the of 35 is of the distance from 30 to 40.

Step 4

The total distance between the bracketing critical values of 2.042 and 2.021 in the

unknown column is .

The of 35 is .50 of the distance between the bracketing , so the target critical

value is .50 of the distance between 2.042 and 2.021, or of .

Step 5

Thus, of the distance between the bracketing critical values is .0105. Because

critical values decrease as increases, we are going from 30 to 35 , so subtract

from the larger value, 2.042.

Step 6

Thus, is the critical value for 35 at for a two-tailed test.

The same logic can be applied to find critical values for any other statistic.

Application Questions

(Answers for odd-numbered questions are in Appendix D.)

1. What is the z-score you must score above to be in the top 25% of scores?

2. Foofy obtains a z-score of 1.909. What proportion of scores are between her score

and the mean?

3. For , what is the two-tailed for ?

4. For , what is the two-tailed for ?

A.3 THE ONE-WAY, WITHIN-SUBJECTS ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE

This section contains formulas for the one-way, within-subjects ANOVA discussed in

Chapter 13. This ANOVA is similar to the two-way ANOVA discussed in Chapter 14,

so read that chapter first.

Assumptions of the Within-Subjects ANOVA

In a within-subjects ANOVA, either the same participants are measured repeatedly or

different participants are matched under all levels of one factor. (Statistical terminol-

ogy still uses the old fashioned term subjects instead of the more modern partici-

pants.) The other assumptions here are (1) the dependent variable is a ratio or interval

variable, (2) the populations are normally distributed, and (3) the population variances

are homogeneous.

df 5 55t

crit

␣ 5 .05

df 5 50t

crit

␣ 5 .05

␣ 5 .05dft 5 2.0315

2.042 2 .0105 5 2.0315

.0105

dfdfdf

.50

1.5021.02125 .0105

.021.50

dfsdf

.021

2.042 2 2.021 5 .021

.50df

df

5

10

5 .50

df

df

35 2 30 5 5

dfs

40 2 30 5 10

dfdfdf

384 APPENDIX A / Additional Statistical Formulas

Logic of the One-Way, Within-Subjects ANOVA

As an example, say that we’re interested in whether a person’s form of dress influences

how comfortable he or she feels in a social setting. On three consecutive days, we ask

each participant to act as a “greeter” for other people participating in a different experi-

ment. On the first day, participants dress casually; on the second day, they dress semi-

formally; on the third day, they dress formally. We test the very unpowerful of 5. At

the end of each day, participants complete a questionnaire measuring the dependent

variable of their comfort level while greeting people. Labeling the independent vari-

able of type of dress as factor A, the layout of the study is shown in Table A.3.

To describe the relationship that is present, we’ll find the mean of each level (col-

umn) under factor A. As usual, we test whether the means from the levels represent dif-

ferent . Therefore, the hypotheses are the same as in a between-subjects design:

Elements of the Within-Subjects ANOVA

Notice that this one-way ANOVA can be viewed as a two-way ANOVA: Factor A (the

columns) is one factor, and the different participants or subjects (the rows) are a second

factor, here with five levels. The interaction is between subjects and type of dress.

In Chapters 13 and 14, we computed the F-ratio by dividing by the mean square within

groups . This estimates the error variance , the variability among scores in

the population. We computed using the differences between the scores in each cell

and the mean of the cell. However, in Table A.3, each cell contains only one score. There-

fore, the mean of each cell is the score in the cell, and the differences within a cell are

always zero. Obviously, we cannot compute in the usual way.

Instead, the mean square for the interaction between factor A and subjects (abbrevi-

ated ) reflects the inherent variability of scores. Recall that an interaction

indicates that the effect of one factor changes as the levels of the other factor change. It

is because of the inherent variability among people that the effect of type of dress will

change as we change the “levels” of which participant we test. Therefore,

is our estimate of the error variance, and it is used as the denominator of the -ratio.

(If the study involved matching, each triplet of matched participants would provide the

F

MS

A3subs

MS

A3subs

MS

wn

MS

wn

1σ

2

error

21MS

wn

2

H

a

: Not all s are equal

H

0

:

1

5

2

5

3

s

N

A.3 The One-Way, Within-Subjects Analysis of Variance 385

ADDITIONAL STATISTICAL FORMULAS

Factor A: Type of Dress

Level A

1

: Level A

2

: Level A

3

:

Casual Semiformal Formal

1XXX

2XXX

Su

Factor

bjects

3XXX

4XXX

5X

苶

XX

X

苶

A

1

X

苶

A

2

X

苶

A

3

TABLE A.3

One-Way Repeated-

Measures Study of the

Factor of Type of Dress

Each X represents a par-

ticipant’s score on the

dependent variable of

comfort level.

scores in each row, and the here would still show the variability among

their scores.)

As usual, describes the difference between the means in factor A, and it estimates

the variability due to error plus the variability due to treatment. Thus, the F-ratio here is

If is true and all s are equal, then both the numerator and the denominator will

contain only , so will equal 1. However, the larger the , the less likely it is

that the means for the levels of factor A represent one population . If is signifi-

cant, then at least two of the means represent different .

Computing the One-Way, Within-Subjects ANOVA

Say that we obtained these data:

Factor A: Type of Dress

Level A

1

: Level A

2

: Level A

3

:

Casual Semiformal Formal

1 491©X

sub

⫽ 14

2 6123©X

sub

⫽ 21

Subjects 3 844©X

sub

⫽ 16

4 285©X

sub

⫽ 15

5 10 7 2 ©X

sub

⫽ 19

Total:

©X ⫽ 30 ©X ⫽ 40 ©X ⫽ 15 ©X

tot

⫽ 30 ⫹ 40 ⫹ 15 ⫽ 85

©X

2

⫽ 220 ©X

2

⫽ 354 ©X

2

⫽ 55 ©X

2

tot

⫽ 220 ⫹ 354 ⫹ 55 ⫽ 629

n

1

⫽ 5 n

2

⫽ 5 n

3

⫽ 5 N ⫽ 15

X

苶

1

⫽ 6 X

苶

2

⫽ 8 X

苶

3

⫽ 3 k ⫽ 3

Step 1 Compute the , the , and the for each level of factor A (each column).

Then compute and . Also, compute , which is the for each partic-

ipant’s scores (each row). Notice that the and are based on the number of scores,

not the number of participants.

Then follow these steps.

Step 2 Compute the total sum of squares.

Nns

©X©X

sub

©X

2

tot

©X

tot

©X

2

X©X

s

F

obt

F

obt

F

obt

σ

2

error

H

0

Sample Estimates Population

F

obt

⫽

ᎏ

MS

M

A

S

⫻

A

subs

ᎏ

→

→

MS

A

MS

A3subs

386 APPENDIX A / Additional Statistical Formulas

σ

2

error

1 σ

2

treat

σ

2

error

The formula for the total sums of squares is

SS

tot

5 ©X

2

tot

2 a

1©X

tot

2

2

N

b

From the example, we have

Note that the quantity is the correction in the following computations.

(Here, the correction is 481.67.)

Step 3 Compute the sum of squares for the column factor, factor A.

1©X

tot

2

2

>N

SS

tot

5 629 2 481.67 5 147.33

SS

tot

5 629 2 a

85

2

15

b

A.3 The One-Way, Within-Subjects Analysis of Variance 387

Find in each level (column) of factor A, square the sum and divide by the n of the

level. After doing this for all levels, add the results together and subtract the correction.

In the example

Step 4 Find the sum of squares for the row factor, for subjects.

SS

A

5 545 2 481.67 5 63.33

SS

A

5 a

1302

2

5

1

1402

2

5

1

1152

2

5

b2 481.67

©X

Square the sum for each subject ( ). Then add the squared sums together. Next,

divide by , the number of levels of factor A. Finally, subtract the correction. In the

example,

Step 5 Find the sum of squares for the interaction. To do this, subtract the sums of

squares for the other factors from the total.

SS

subs

5 493 2 481.67 5 11.33

SS

subs

5

1142

2

1 1212

2

1 1162

2

1 1152

2

1 1192

2

3

2 481.67

k

©X

sub

The formula for the sum of squares between groups for factor A is

SS

A

5 © a

1Sum of scores in the column2

2

n of scores in the column

b2 a

1©X

tot

2

2

N

b

The formula for the sum of squares for subjects is

SS

subs

5

1©X

sub1

2

2

1 1©X

sub2

2

2

1

. . .

1 1©X

n

2

2

k

2

1©X

tot

2

2

N

The formula for the interaction of factor a by subjects is

SS

A3subs

5 SS

tot

2 SS

A

2 SS

subs

ADDITIONAL STATISTICAL FORMULAS