Gramley, Stephan; P?tzold, Kurt-Michael. A Survey of Modern English

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Vocabulary

In this and the next chapter the words of the modern English language will be at the

centre of our discussion. Chapter 3 will focus on combinations of words (so-called multi-

word units like idioms and proverbs). In this chapter the English vocabulary will be

looked at from various points of view: the concept of word and the relationship between

words and meaning; the major types of dictionaries; the structure and development of the

English vocabulary; new words in the media and the Internet; euphemisms; non-sexist

language; word formation; how words change their meanings; and a model commonly

useful in the analysis of the English vocabulary.

2.1 WORDS AND MEANING

The vocabulary of the English language is conveniently recorded in dictionaries, of which

the second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (1989; abbreviated as OED2 in the

following) is the most recent and comprehensive. Although many people think it the

greatest dictionary in the world, reviewers have no difficulty in pointing to words and

phrases that are missing. Linguists draw a distinction between dictionaries, which are

only incomplete recordings of the English vocabulary, and its total word stock, which

they refer to as its lexis or lexicon.

It is not only because new words are coined all the time that it is impossible to say

precisely how many words there are in English. It is also because of the vagueness of the

everyday term word. For example, how often is the word dictionary used in the preceding

paragraph? Dictionary (with a capital D) and dictionary are each found once while there

are two examples of dictionaries. If we say that there are three different words

(Dictionary, dictionary, dictionaries) we are simply referring to the physical shape of

words, in this instance the black marks that appear on the paper of this book. Linguists

have coined the term word form for this use of word (word forms are conventionally

quoted in italics). From a different point of view we might say that there are two exam-

ples of dictionary, one in the singular and the other in the plural. Linguists use word to

refer to this second, grammatical, use (no special conventions). If we say, finally, that

there are four occurrences of the single word

DICTIONARY

we are basing our answer on

the fact that, though different words and word forms are involved, they all show the same

meaning. Word forms seen from the meaning point of view are called lexemes or lexical

items (and are given in small caps). As lexemes can have many meanings, the need has

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

Chapter 2

been felt for a term which refers to the combination of one meaning with one word form.

This is called a lexical unit. The lexeme

OLD

for instance represents at least two different

lexical units. This becomes clear when you think of the opposite of

OLD

: one antonym

is

YOUNG

, but

OLD

in my old boyfriend contrasts with

NEW

rather than

YOUNG

. What

we find as main entries in dictionaries are lexemes, while each of the various meanings

listed in these entries are lexical units. Having said all this, we will generally use the

everyday term word in this book.

Words (in whatever sense) are, however, not the smallest meaningful units recognized

in linguistics. Word formation goes beyond words such as {star} (called free morphemes

because they can stand alone) and also recognizes forms such as {-dom} as meaningful.

(Each of these morphemes is conventionally enclosed in braces or curly brackets.)

The latter is a bound morpheme, which means it occurs only in combination with free

morphemes (combining forms are an exception – they can combine with each other

although they cannot stand alone, see below 2.7.4). On the other hand, it is no less

important to recognize that there are combinations of more than one word, so-called multi-

word units, like the idiom pull someone’s leg or the proverb he who pays the piper calls

the tune, which linguists regard as lexical items in their own right (see Chapter 3).

Dictionaries often differ in whether they include not only free morphemes, but also bound

morphemes, idioms and proverbs in their entries.

In the case of dictionary there is likely to be universal agreement that it is a word (in

all of the senses), not least because it is easy to state its meaning. It is quite different for

words like the, mine or upon. These grammatical or closed set items (e.g. articles,

pronouns, prepositions) have grammatical functions rather than lexical meanings (e.g. the

to in he likes to play chess). Indeed, they are also called function words because their

grammatical function is often more important than their meaning. Lexical words, i.e.

words with a distinctly lexical meaning, on the other hand, are members of the classes

noun, verb, adjective and (partially) adverb: these are classes that do not have a limited

set of members but which are constantly being added to. Such lexical items are therefore

often called open-class items. Grammatical words can have weak stress and occur with

high frequency; lexical items have strong stress.

The combination of word forms with meaning is also unproblematic in the case of

dictionary because there are only one or two meanings (lexical units) involved. There are,

however, many words which have a great number of meanings. Different linguists and

lexicographers have different views on how many lexical units or lexemes to postulate

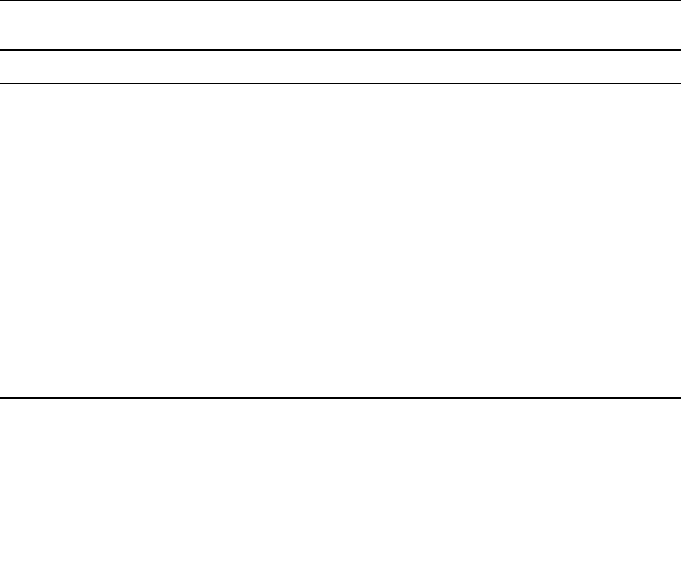

in these cases. Table 2.1 shows how a few dictionaries deal with such a more compli-

cated example, namely romance.

2.2 LEXICAL RELATIONSHIPS

Polysemy and homonymy Table 2.1 mirrors the difficulties involved in deciding

whether to view a given word form with several meanings as a case of polysemy (the

existence of one lexeme with many related meanings) or of homonymy (the existence of

different lexemes that sound the same (homophones) or are spelt the same (homographs)

but have different, unrelated meanings). In the latter case we find separate main entries.

Whereas AHD and COBUILD set up one main entry (= one lexeme), NODE offers two,

while LDOCE has three main entries. Another finding is that LDOCE and COBUILD do

24 ENGLISH AS A LINGUISTIC SYSTEM

not record three of the senses of the noun. This is because they are dictionaries for foreign

learners that offer a more restricted coverage of lexical units. For more on types of diction-

aries, see 2.3.

Synonymy The distinction between homonyms and polysemous items has raised the

question of semantic similarity and difference. Sets of lexical units that have identical, or

near identical, meanings are referred to as synonyms. Theoretically they can take each

other’s place in any context but in practice there are always differences. Take the nouns

holiday, vacation, leave and furlough, for example, which can all refer to a period of time

when you do not do your usual work. Note how they differ in the words they occur with

(their collocations, see Chapter 3): Sailors go on leave, but soldiers and people who work

abroad go on furlough. Leave is often found in compounds such as sick leave, maternity

leave and unpaid leave. Vacation is used in AmE like the GenE holiday(s) and can refer

in both BrE and AmE to the time when no teaching is done at colleges and universities,

although the informal short form vac for a university break (as in long vac) is restricted

to BrE (the word form vac in AmE is an abbreviation of vacuum cleaner). Informal, short-

ened hols is also BrE but is, in addition, somewhat old fashioned (public school) language.

It is usual to say that synonyms share their denotation, or central meaning, while they

differ in their connotations, whether regional, social, stylistic or temporal aspects.

Hyponymy and meronymy Other relationships between words in word fields are

hyponymy, or inclusion, which relates a general to a more specific term, e.g. flower, on

the one hand, and fuchsia, marigold or rose, on the other. Lexical units such as flower

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

VOCABULARY 25

Table 2.1 Some dictionary entries for romance

NODE AHD LDOCE COBUILD

romance (noun)

atmosphere ++++

love (affair) ++++

literary genre/work ++++

medieval tale ++++

exaggeration, falsehood 0 + 0 0

language family R + R 0

piece of music + + 0 0

romance (adjective)

relating to the Romance language

family R + 0 +

romance (verb)

exaggerate + 0 r 0

court, woo + + r +

Notes: NODE = The New Oxford Dictionary of English, Oxford 1998. AHD = The American Heritage College

Dictionary, 3rd edn, Boston 1993. LDOCE = Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, 4th edn, Harlow

2003. COBUILD = Collins COBUILD English Dictionary, 3rd edn, London 2001

+ = contained in main or only entry

r = additional main entry, small letter

R = additional main entry, capital letter

0 = not recorded

are called superordinate terms while what they include are their (co-)hyponyms.

Meronymy, in contrast, is a part–whole relationship with the parts being different from

the (superordinate) whole, as in church versus aisle, transept, chapel and steeple.

Opposition The relationship between the days of the week and the months of the year

is called incompatibility, or heteronomy, and involves more than two members of a

category which share one or more meaning elements and are mutually exclusive.

Antonymy also holds between two or more members of the same category but here the

members are arranged on a scale with clear end points, called antonyms, e.g. hot and

cold, with warm, lukewarm and cool taking up positions between the extremes. It should

again be noted that the same word form can be antonymous with more than one other

word form: old–new (car) and young–old (man). This makes it clear that semantic rela-

tionships hold between lexical units, not lexemes. Complementarity is a distinct case of

semantic opposition. It refers to absolute contrasts like dead and alive, married and single:

if you use the one term then you have to deny the other. While antonymy allows compar-

atives (hotter, colder), complementarity does not (*deader). Related to complementary

pairs are converses, like lend and borrow, husband and wife, which look at the same rela-

tionship from different perspectives: the sentence she is his wife can be reversed to

produce the reciprocal correlate he is her husband. When converses express movements

in opposite directions they can be called reverses, e.g. come and go, to and fro, up and

down. For an example of how lexical relationships work in texts see 6.2 and 6.3.

2.3 DICTIONARIES

Mental lexicon It has been said that all dictionaries are out of date as soon as they

are published: this is so because no dictionary can hope to include all the lexemes that

are stored in the brains of its speakers. The vocabulary stored in the minds of the speakers

of a language is called the mental lexicon. It is not only much larger than any published

dictionary, it is also structured quite differently: its arrangement includes and goes beyond

the alphabet and may be based on similarity (or contrast) in sound and, above all, meaning.

This means that synonyms and antonyms are stored closely together in the brain, but also

variants in syntax and pronunciation, information on the currency, frequency and social

acceptance of lexemes as well as such features as the age, gender and social status of its

speakers. The mental lexicon is therefore a complex, comprehensive and ever changing

structure that no print or electronic dictionary can compete with, although thesauruses,

field and learner dictionaries make use of some non-alphabetical structural principles.

An important general distinction is that between printed or print dictionaries and

those on CD-ROM. Electronic dictionaries save space on your book shelves and tend

to be quicker to use while perhaps giving less physical pleasure. What is crucial to realize

is that there are different types of CD-ROM dictionaries. One type, often available for

free, offers the text of a printed dictionary in electronic form and can only be used to

access main entry words. Another type tends to make full use of the electronic medium

by including visual and video materials and allows users to search for words in the

complete text of the dictionary (this is called full-text search), which often finds more

words than are listed as head words: OED2, for instance, has no entry for the verb free

up but a full-text search comes up with two examples. Such a search gives you a complete

26 ENGLISH AS A LINGUISTIC SYSTEM

set of examples (or concordance) in the context of the item searched for, which is invalu-

able for language teaching as well as a full linguistic description. This more sophisticated

type of CD-ROM must usually be bought separately and can cost more than the print

edition, but it is money well spent. In the following, dictionaries will be referred to by

short titles, while a classified list of dictionaries with full references can be found in the

Bibliography of dictionaries at the end of this book.

2.3.1 Dictionaries for scholars and native speakers

The two major groups of dictionaries for the purposes of this book are those that are

published with a native speaker audience in mind and those that are meant for people

whose first language is not English.

Historical dictionaries OED2 represents an outstanding lexicographic achievement.

It offers the most up-to-date research into every aspect of lexemes: the history and present

state of their spelling, pronunciation and meaning, together with their relationships

with words in other languages and many examples, fully dated, referenced and arranged

chronologically. The third edition, now being published on the Internet, makes up

for former shortcomings with, for example, a better coverage of colloquialisms, native

speaker varieties of English around the world and more careful and updated etymologies.

Following the OED’s model, many other English speaking countries have produced their

national dictionaries on historical principles.

Desk dictionaries For everyday use large, unabridged dictionaries are too unwieldy

and extensive. In their place users turn to desk (the BrE term) or college (the AmE term)

dictionaries, of which the American volumes had entries for people, places and events

(so-called encyclopedic entries) long before their British counterparts, some of which

still do not have this type of information (e.g. the Concise Oxford Dictionary and the

New Penguin Dictionary of English).

Conceptual dictionaries and thesauruses While the dictionaries mentioned so

far are all arranged in alphabetical order, the concept(ual) or thematic dictionary

arranges its words in groups by their meaning. The first fully-fledged work of this kind

was published by P.M. Roget (Thesaurus of English Words and Phrases, 1852), and has

appeared in many revised and expanded editions since then.

2.3.2 Non-native speaker dictionaries

The thesaurus type of dictionary is typical of native speaker dictionaries in that it usually

gives long lists of words without illustrative examples or other information on how to

use them. Thesauruses are for people who know their English, and they cannot be recom-

mended to learners of English, who need to be shown how words behave in context so

that they can really use them. The only thesaurus to do that is the Longman Lexicon.

Learner dictionaries Desk dictionaries for people with English as their first

language (or L1-dictionaries, to use the technical term) have word lists (referred to as

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

VOCABULARY 27

the macrostructure) in excess of 150,000 items and usually give their etymologies.

Dictionaries for foreign learners (or L2-dictionaries), on the other hand, have so far not

offered etymologies nor do their word lists exceed 100,000 words and phrases. Again,

native speaker dictionaries are meant for people who want to find out the meaning,

pronunciation and spelling of words they do not know. In contrast, dictionaries for non-

native speakers, while giving similar semantic, phonetic and orthographic help, also

include information on how a word behaves syntactically, what word combinations or

collocations it enters into and how it differs from words with similar meanings (synonym

discrimination). While both dictionary types indicate whether a word is formal or

informal, taboo or vulgar, the learner dictionaries take greater care to explain the meaning

of words in simple English, often using a restricted number of words to do this (between

2,000 and 3,000 items). They also lead readers quickly to the various lexical units of

lexemes, for which they use brief glosses that come before definitions; provide a great

number of (sentence) examples, both British and American English equivalents in

pronunciation and vocabulary (e.g. ‘UK pavement, see sidewalk US’ ), and special usage

notes, which demonstrate the correct, and warn against the incorrect, use of words.

To make a pointed, if not wholly accurate contrast: L1-dictionaries are satisfied with

helping you to find out about words (here one speaks of decoding dictionaries) while

L2-dictionaries take much greater pains to help you produce correct and idiomatic English

(production dictionaries, also referred to as encoding dictionaries).

Dictionaries of word combinations These have a much reduced macrostructure

but offer a detailed microstructure, listing the most important lexical and syntactic

combinations, and often a good selection of fixed expressions such as phrasal verbs

which are an important, because very frequent, type of verb in English.

Dictionaries of cultural literacy Language is of course only one aspect of the

culture of the countries where English is spoken. If you want to understand English

language texts you also need to be aware of people, places, events, the arts, amusement

and leisure activities, allusions to, or quotations from, mythology, the Bible, Shakespeare

etc. and the meanings and connotations they have for native speakers.

Quite a number of dictionaries, both of the native and non-native speaker varieties are

available on the Internet (for details see the Bibliography of dictionaries).

2.4 GROWTH AND STRUCTURE OF THE ENGLISH

VOCABULARY

The English vocabulary, as with all languages, grows either by borrowing from external

sources (these are called loan formations) or by internal means, using English word

formation processes and, to a much smaller extent, by a combination of the two.

English has changed dramatically over the centuries from a language whose lexis was

almost completely Germanic (in Old English times, that is, up to about 1100) to one which

has taken in words from all the major languages of the world. Foreign influence shows

in loan words as well as loan translations and loan shifts, where only the meaning, but

not the form, has been borrowed, see OE cneoht ‘farm hand’ > ModE knight under the

influence of Old French chevaler.

28 ENGLISH AS A LINGUISTIC SYSTEM

2.4.1 The three layers

By far the most important non-native items in English are those from French and the

classical languages, Latin and Greek. Together they give us three historical layers: an

Anglo-Saxon, a French and a classical one, each with its own characteristics. French

loans have made their way into the language since the Norman Conquest of England in

1066; and although they were originally part of the class dialect of the new rulers, they

have in the meantime, lost their connotations of prestige, social superiority or courtliness

and have become part of the central core of English lexis. French-derived words are promi-

nent for instance in the fields of art and architecture, fashion, religion, hunting, war and

politics, but they are especially prominent in food and cooking.

How can the different strata be distinguished and characterized? English often

uses Anglo-Saxon words for raw materials and basic processes while words for finished

products and more complicated processes come from the French. A classic example

of this, mentioned by Sir Walter Scott in the first chapter of his novel Ivanhoe, are the

Anglo-Saxon animal terms pig/sow, cow and calf as opposed to their meat, pork, beef and

veal. While cook is Anglo-Saxon, boil, broil, fry, grill and roast are French, as is chef.

There is a similar division, this time between the names for the raw materials and the

tradesmen, in Anglo-Saxon beard, hair, cloth, meat, stone and wood as opposed to barber,

tailor, butcher, mason and carpenter.

While French contributed a great many terms from the realms of power and the higher

arts of living and working, classical loans have provided English as well as most other

(European) languages with countless technical terms in all branches of human knowledge,

a need that was strongly felt by English humanists of the sixteenth century, who wanted

English to become a medium capable of expressing the most refined thoughts, on a par

with Latin and Greek (see also 6.6.2). Lexis, lexeme, lexical, lexicographer, diction(ary)

and vocabulary are all derived from Latin and Greek elements, while only the rarer items

word book and word stock are Germanic in origin.

An illustration of the interplay between Anglo-Saxon, French and Latin/Greek is

provided by kinship terms, where the basic words go back to Anglo-Saxon times (father,

mother, husband, wife; son, daughter, sister and brother), while grandmother and grand-

father are hybrid formations, consisting of elements from more than one language, in

this case French (grand) and Anglo-Saxon father and mother. Aunt (first recorded in the

OED in 1297) and uncle (1290) come from the Latin via French as do niece and nephew

(1297) while family (1545) has been imported directly from the Latin.

How does English form adjectives to go with these kinship nouns? One way is forma-

tions with the suffix {-ly}, of which only four are at all frequent, namely fatherly,

motherly, brotherly and sisterly. They show meanings that range from neutral to (more

often) positive: a motherly woman is kind and gentle, and so is fatherly advice.

Daughterly, sonly, husbandly and wifely are old-fashioned and regularly used only when

one wants to be humorous, ironic or self-consciously archaic or to characterize someone

as pompous. Formations with {-like} (daughter-, son-like etc.), though listed in some

dictionaries, do not seem to be in wide use either. Modern English uses genitive construc-

tions (a mother’s love, father’s behaviour, daughter’s duty etc.) in neutral contexts

while it employs various Latin-derived adjectives in formal contexts, such as filial (= of

a son or daughter), which is found in frequent combination with love, obedience, piety.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

VOCABULARY 29

Avuncular (1831) goes with uncle but has the more general meaning of ‘behaving in a

kind way towards younger people, like an uncle does to his nieces and nephews’.

In addition, there are a number of quasi-synonymous adjectives: maternal competes

with motherly, paternal with fatherly, soror(i)al with sisterly, and fraternal with broth-

erly. While maternal and paternal can have the same positive meaning as motherly and

fatherly (maternal/paternal affection), they are perhaps more often used neutrally to refer

to an ancestor, as in my maternal/paternal grandmother, i.e. my grandmother on my

mother’s/father’s side. Maternal and paternal are also often used in scholarly and formal

contexts, e.g. paternal/maternal line (in anthropology). Fraternal is perhaps most

common in the collocation fraternal twin, where it contrasts with identical twin, while

sororal polygyny is used in anthropology to refer to the custom of preferring the first

wife’s sister(s) as secondary wives. Similar differences in formality and meaning are

found between fatherhood and paternity, motherhood and maternity. An abstract term to

refer to the relations between members of a family is the French-derived consanguinity

(c.1380), to which were added blood-relationship (1709) and kinship (1866) in mid

Victorian England.

To sum up this discussion: most of the basic terms, simple and derived, are Anglo-

Saxon, stylistically neutral and often associated with positive feelings, while the more

peripheral and abstract terms come from French and Latin, are often found in formal

contexts and carry specialized meanings. The English vocabulary is, then, a good example

of a lexically mixed language, but that is true only with reference to the 616,500 word

forms which we find in the OED. The three layers differ significantly in their share

of the vocabulary and their frequency of use. It has been calculated that a majority of

words, 64 per cent, in the Shorter Oxford Dictionary come from Latin, French and Greek

while the Germanic element amounts to no more than 26 per cent. On the other hand,

when we look at the items actually used in writing and speaking we find that the front

runners are native English words. Of the roughly 4,000 most frequent words 51 per cent

are of Germanic origin and 48 per cent of Latin and Romance origin while the Greek

element is negligible. The 12 most frequent verbs in the Longman Spoken and Written

English Corpus are all Germanic – say, get, go, know, think, see, make, come, take,

want, give and mean. This shows the paramount importance of the inherited Germanic

vocabulary in the central core of English. Loan words from French and Latin or Greek

are, as we have seen, more peripheral, though relative frequencies vary by text type

(see 6.3) and stylistic level: the more formal the style and the more specialized and remote

from everyday experience the subject matter, the higher the number of loans will usually

be. In everyday language, the English word will often be preferred because it is vague

and covers many shades of meaning, while loan words tend to be more precise and

restricted and so more difficult to handle. Thus, when faced with the choice between

acquire, obtain and purchase, on the one hand, and buy or get on the other, most people

will go for the short Anglo-Saxon words. In formal situations it may seem appropriate to

extend or grant a cordial reception, while in less stiff situations you will give a warm

welcome. The old-established items are usually warmer, more human, more emotional,

while many (polysyllabic) loans from Greek, Latin or the Romance languages are cold

and formal and put a distance between sender (speaker, writer) and addressee (listener,

reader).

30 ENGLISH AS A LINGUISTIC SYSTEM

2.4.2 Hard words and their consequences

Several reasons have been put forward for the difference between overall distribution and

actual use of the vocabulary. The emotional and everyday character of the native words

makes them the words of choice for most situations. Another reason would seem to be

the embarrassment of riches (a loan translation of French embarras de richesse) in English

which can have two or three different lexemes (of different origins) to express a given

meaning. This wealth of expressions is a welcome challenge for highly educated people

with time on their hands but has always posed problems for the average native speaker.

This is, incidentally, also one reason for the advent of English dictionaries at the end of

the sixteenth century, at the height of the influx of learned loan words from the classical

languages: they started as word lists that explained these difficult hard words to people

with little formal education.

Besides being difficult to pronounce and spell, hard words are difficult for people

without a knowledge of Latin because they often cannot easily be related to other words.

Verbs like defer, prefer, infer or assist, desist and insist have to be learnt separately

because English does not have the roots *{-fer} or *{-sist}. This also goes for such

formally similar items as pathos, pathetic and the combining form {patho-} (as in

pathogen or pathological).

The semantic difficulties of hard words are increased by formal problems. If you have

social aspirations, you might well think a mastery of these erudite words the royal road

to social status and advancement, as in this example where a socially adroit young

American WASP (= White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) wants to impress his wife’s senior

colleague and his female partner, a head teacher:

She should have known better than to doubt Jazz’s social skills. . . . She did note,

however, that he was aiming an inordinate number of four and five-syllable words

at the headmistress when shorter ones would have done fine. Their discussion was

fairly straightforward and . . . innocuous . . . such purposely inoffensive conversation

did not require ‘eventuate’ and ‘dissimilitude’ on Jazz’s part. Fortunately, he calmed

down later, reverting to short, friendly words

(S. Isaacs, Lily White, New York 1997, p. 429)

Jazz is only one of many fictional characters in English language literature since

Shakespeare who try to make social capital out of their command of Latinisms. While

Jazz is well educated and therefore brings off this linguistic feat – and, as he relaxes,

returns to Anglo-Saxon words, which are much more appropriate to the party atmosphere

– many other fictional characters are less certain of their hard words and are made fun

of for getting their Latinisms wrong; for example, using paradigm where paragon is

intended (‘The Council is not a paradigm of virtue’). Huck Finn, knowing that difficult

words are monstrously long, produces preforeordestination instead of comparatively

humble predestination (The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapter 18). This blunder,

called a malapropism, is not merely funny or confined to literature: an incensed crowd

in England recently threatened a paediatrician (children’s doctor) because they thought

she was a paedophile, a person who is sexually attracted to children.

There can, then, be no doubt that hard words pose major problems. What have English

speakers done to come to grips with these difficulties? There are various phenomena that

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3

4111

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5111

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

44

45

46

47111

VOCABULARY 31