Gary Nichols. Sedimentology and Stratigraphy(Second Edition)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

a volcanic arc (Fig. 24.8). The magmas start to form

when the downgoing slab reaches 90 to 150 km

depth. The arc–trench gap (distance between the

axis of the ocean trench and the line of the volcanic

arc) will depend on the angle of subduction: at steep

angles the distance will be as little as 50 km and

where subduction is at a shallow angle it may be

over 200 km.

Arc–trench systems are regions of plate conver-

gence, however, the upper plate of an active arc

must be in extension in order for magmas to reach

the surface and generate volcanic activity. The

amount of extension is governed by the relative

rates of plate convergence and subduction and this

is in turn influenced by the angle of subduction. If the

angle of subduction is steep then convergence is

slower than subduction at the trench, the upper

plate is in net extension and an extensional backarc

basin forms (Dickinson 1980). Steep subduction

occurs if the downgoing plate consists of old, cold

crust. However, not all backarc areas are under

extension: some are ‘neutral’ and others are sites of

the formation of a flexural basin due to thrust move-

ments at the margins of the arc massif (retroarc

basins).

24.3.1 Trenches (Fig. 24.9)

Ocean trenches are elongate, gently curving troughs

that form where an oceanic plate bends as it enters a

subduction zone. The inner margin of the trench is

formed by the leading edge of the overriding plate of

the arc–trench system. The bottoms of modern

trenches are up to 10,000 m below sea level, twice

as deep as the average bathymetry of the ocean

floors. They are also narrow, sometimes as little as

5 km across, although they may be thousands of

kilometres long. Trenches formed along margins

flanked by continental crust tend to be filled with

sediment derived from the adjacent land areas.

Intra-oceanic trenches are often starved of sediment

because the only sources of material apart from pela-

gic deposits are the islands of the volcanic arc. Trans-

port of coarse material into trenches is by mass flows,

especially turbidity currents that may flow for long

distances along the axis of the trench (Underwood &

Moore 1995).

24.3.2 Accretionary complexes

The strata accumulated on the ocean crust and in a

trench are not necessarily subducted along with the

crust at a destructive plate boundary. The sediments

may be wholly or partly scraped off the downgoing

Fig. 24.8 Arc–trench systems include chains of volcanoes

that form the arc.

Backarc basin

Forearc basin

Trench

continental crust

oceanic crust

volcanic arc

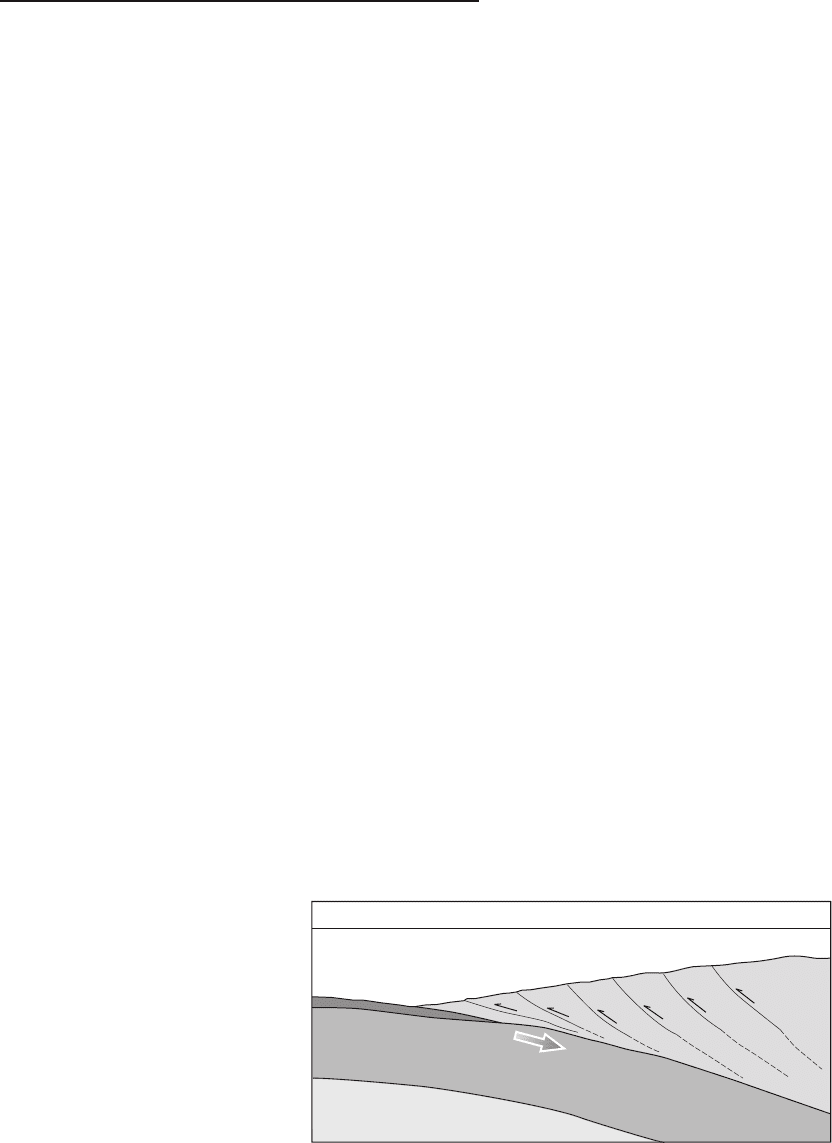

Fig. 24.9 Forearc basins, trenches

and extensional backarc basins are

supplied by volcaniclastic material

from the adjacent arc and may also

receive continentally derived detritus if

the overriding plate is continental

crust.

388 Sedimentary Basins

plate and accrete on the leading edge of the overriding

plate to form an accretionary complex or accretion-

ary prism. These prisms or wedges of oceanic and

trench sediments are best developed where there are

thick successions of sediment in the trench (Einsele

2000). A subducting plate can be thought of as a

conveyor belt bringing ocean basin deposits, mainly

pelagic sediments and turbidites, to the edge of the

overriding plate. In some places this sediment is car-

ried down the subduction zone, but in others it is

sliced off as a package of strata that is then accreted

on to the overriding plate (Fig. 24.10).

24.3.3 Forearc basins (Fig. 24.9)

The inner margin of a forearc basin is the edge of

the volcanic arc and the outer limit the accretionary

complex formed on the leading edge of the upper

plate. The width of a forearc basin will therefore be

determined by the dimensions of the arc–trench gap,

which is in turn determined by the angle of subduc-

tion. The basin may be underlain by either oceanic

crust or a continental margin (Dickinson 1995). The

thickness of sediments that can accumulate in a fore-

arc setting is partly controlled by the height of the

accretionary complex: if this is close to sea level the

forearc basin may also fill to that level. Subsidence in

the forearc region is due only to sedimentary loading.

The main source of sediment to the basin is the vol-

canic arc and, if the arc lies in continental crust, the

hinterland of continental rocks. Intraoceanic arcs are

commonly starved of sediment because the island-arc

volcanic chain is the only source of detritus apart

from pelagic sediment. Given sufficient supply of det-

ritus a forearc basin succession will consist of deep-

water deposits at the base, shallowing up to shallow-

marine, deltaic and fluvial sediments at the top

(Macdonald & Butterworth 1990). Volcaniclastic deb-

ris is likely to be present in almost all cases.

24.3.4 Backarc basins (Fig. 24.9)

Extensional backarc basins form where the angle of

subduction of the downgoing slab is steep and the rate

of subduction is greater than the rate of plate conver-

gence. Rifting occurs in the region of the volcanic arc

where the crust is hotter and weaker. At this stage an

‘intra-arc basin’ forms, a transient extensional basin

that is bound on both sides by active volcanoes and is

the site of accumulation of mainly volcanically

derived sediment. With further extension the arc com-

pletely splits into two parts, an active arc with con-

tinued volcanism closer to the subduction zone and a

remnant arc. As divergence between the remnant and

active arcs continues a new spreading centre is

formed to generate basaltic crust between the two.

This backarc basin continues to grow by spreading

until renewed rifting in the active arc leads to

the formation of a new line of extension closer to the

trench. Once a new backarc basin is formed the

older one is abandoned. The lifespan of these basins

is relatively short: in the Western Pacific Cenozoic

backarc basins have existed for around 20 Myr

between formation and abandonment. Extensional

backarc basins can form in either oceanic or conti-

nental plates (Marsaglia 1995). The principal source

of sediment in a backarc basin formed in an oceanic

plate will be the active volcanic arc. Once the rem-

nant arc is eroded down to sea level it contributes

little further detritus. More abundant supplies are

Fig. 24.10 Sediment deposited in an

ocean trench includes both material

derived from the overriding plate and

pelagic material. As subduction pro-

ceeds sediment is scraped off the

downgoing plate to form an accre-

tionary prism of deformed sedimentary

material.

Accretionary prism

Sea level

Subduction of oceanic crust

Ocean

trench

Thrusts

Basins Related to Subduction 389

available if there is continental crust on either or both

sides of the basin. Backarc basins are typically under-

filled, containing mainly deep-water sediment of vol-

caniclastic and pelagic origin.

24.4 BASINS RELATED TO CRUSTAL

LOADING

When an ocean basin completely closes with the total

elimination of oceanic crust by subduction the

two continental margins eventually converge.

Where two continental plates converge subduction

does not occur because the thick, low-density conti-

nental lithosphere is too buoyant to be subducted.

Collision of plates involves a thickening of the litho-

sphere and the creation of an orogenic belt, a moun-

tain belt formed by collision of plates. The Alps have

formed by the closure of the Tethys Ocean as Africa

has moved northwards relative to Europe, and the

Himalayas (Fig. 24.11) are the result of a series of

collisions related to the northward movement of

India. The edges of the two continental margins that

collide are likely to be thinned, passive margins.

Shortening initially increases the lithosphere thick-

ness up to ‘normal’ values before it overthickens. As

the crust thickens it undergoes deformation, with

metamorphism occurring in the lower parts of the

crust and movement of material outwards from the

core of the orogenic belt along major fault planes. In

the shallower levels of the mountain belt, low-angle

faults (thrusts) also move rock outwards, away from

the centre of the belt. This combination of movement

by thick-skinned tectonics (which involves faults

that extend deep into the crust) and thin-skinned

tectonics (superficial thrust faults) transfers mass lat-

erally and results in a loading of the crust adjacent to

the mountain belt. This crustal loading results in the

formation of a ‘peripheral’ foreland basin.

Crustal loading can also occur in settings other than

the collision between two blocks of continental crust.

At ocean–continent convergence settings, shortening

in the overriding continental plate and subduction-

related magmatism can also create a mountain belt.

The Andes, along the western margin of South Amer-

ica, have been uplifted by crustal thickening and the

intrusion of magma associated with subduction to the

west. Thrust belts on the landward side of mountain

chains in these settings result in loading and the for-

mation of a ‘retroarc’ foreland basin.

24.4.1 Peripheral foreland basins (Fig. 24.12)

Loading of the foreland crust either side of the orogenic

belt causes the crust to flex in the same way that adding

a mass to the unsupported end of a beam will cause it to

bend downwards. The crust is not wholly unsupported,

but the mantle/asthenosphere below the lithosphere is

mobile and allows a flexural deformation of the loaded

crust to form a peripheral foreland basin. The width

of the basin will depend on the amount of load and the

flexural rigidity of the foreland lithosphere, the ease

with which it bends when a load is added to one end

(Beaumont 1981). Rigid (typically older, thicker)

lithosphere will respond to form a wide, shallow

basin, whereas younger, thinner lithosphere flexes

more easily to create a narrower, deeper trough.

Increasing the load increases the basin depth.

In the initial stages of foreland basin formation the

collision will have only proceeded to the extent of

thickening the crust (which was formerly thinned at

a passive margin) up to ‘normal’ crustal thickness.

Although this results in a load on the foreland and

Fig. 24.11 The major mountainous areas of the world

occur in areas of plate collision where an orogenic belt forms.

390 Sedimentary Basins

lithospheric flexure, the orogenic belt itself will not be

high above sea level at this stage and little detritus will

be supplied by erosion of the orogenic belt. Early fore-

land basin sediments will therefore occur in a deep-

water basin, with the rate of subsidence exceeding the

rate of supply. Turbidites are typical of this stage.

When the orogenic belt is more mature and has built

up a mountain chain there is an increase in the rate of

sediment supply to the foreland basin. Although the

load on the foreland will have increased, the sediment

supply normally exceeds the rate of flexural subsi-

dence. Foreland-basin stratigraphy typically shallows

up from deep water to shallow marine and then con-

tinental sedimentation, which dominates the later

stages of foreland-basin sedimentation (Miall 1995).

The stratigraphy of a foreland-basin fill is compli-

cated by the fact that thrusting, and hence loading, at

the margin of the basin continues as the basin evolves.

The basin will tend to become larger with time as more

load is added, and the later deformation at the margin

will include some of the earlier basin deposits. Erosion

and reworking of older basin strata into the younger

deposits are common. As a consequence, the full suc-

cession of basin deposits will not be exposed in a single

profile. Sometimes thrusting is not restricted to the

basin margin, and may subdivide the basin to form

piggy-back basins (Ori & Friend 1984) that lie on

top of the thrust sheets and which are separate from

the foredeep, the basin in front of all the thrusts.

24.4.2 Retroarc foreland basins (Fig. 24.13)

Thickening of the crust in the continental magmatic

arc results in the landward movement of masses of

rock along thrusts. The loading of the crust on the

opposite side of the arc to the trench results in flexure,

and the formation of a basin: these basins are called

retroarc foreland basins because of their position

behind the arc. The continental crust will be close to

sea level at the time the loading commences so most

of the sedimentation occurs in fluvial, coastal and

shallow marine environments. Continued subsidence

occurs due to further loading of the basin margin by

thrusted masses from the mountain belt, augmented

by the sedimentary load. The main source of detritus

is the mountain belt and volcanic arc.

24.5 BASINS RELATED TO STRIKE-

SLIP TECTONICS

If a plate boundary is a straight line and the relative

plate motion purely parallel to that line there would

be neither uplift nor basin formation along strike-slip

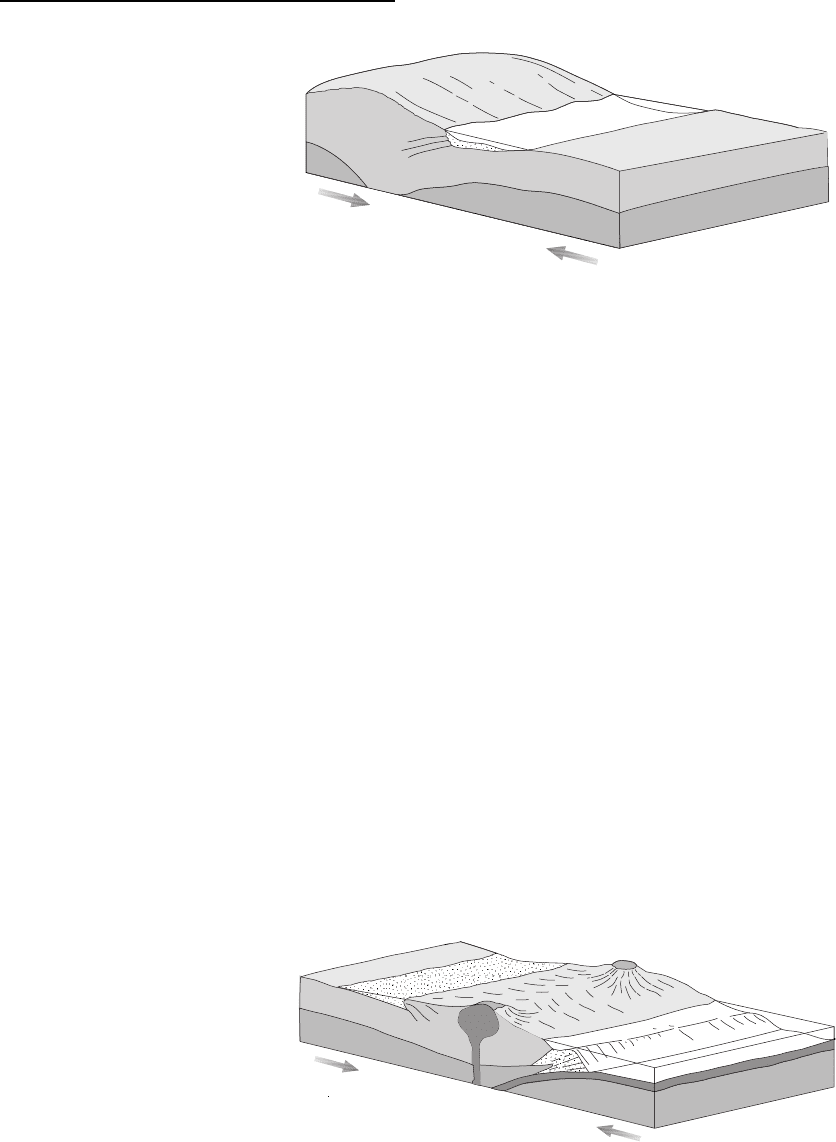

Fig. 24.12 Collision between two

continental plates results in the for-

mation of an orogenic belt where

there is thickening of the crust: this

results in an additional load being

placed on the crust either side and

causes a downward flexure of the

crust to form peripheral foreland

basins.

Peripheral foreland basin

continental crust

orogenic belt

Fig. 24.13 The thickness of the crust

increases due to emplacement of

magma in a volcanic arc at a conti-

nental margin, resulting in flexure of

the crust behind the arc to form a

retroarc foreland basin.

Retroarc foreland basin

Forearc basin

Trench

volcanic arc

continental crust

oceanic crust

Basins Related to Strike-slip Tectonics 391

plate boundaries. However, such plate boundaries are

not straight, the motion is not purely parallel and they

consist not of a single fault strand but of a network of

branching and overlapping individual faults. Zones of

localised subsidence and uplift create topographic

depressions for sediment to accumulate and the source

areas to supply them (Christie-Blick & Biddle 1985).

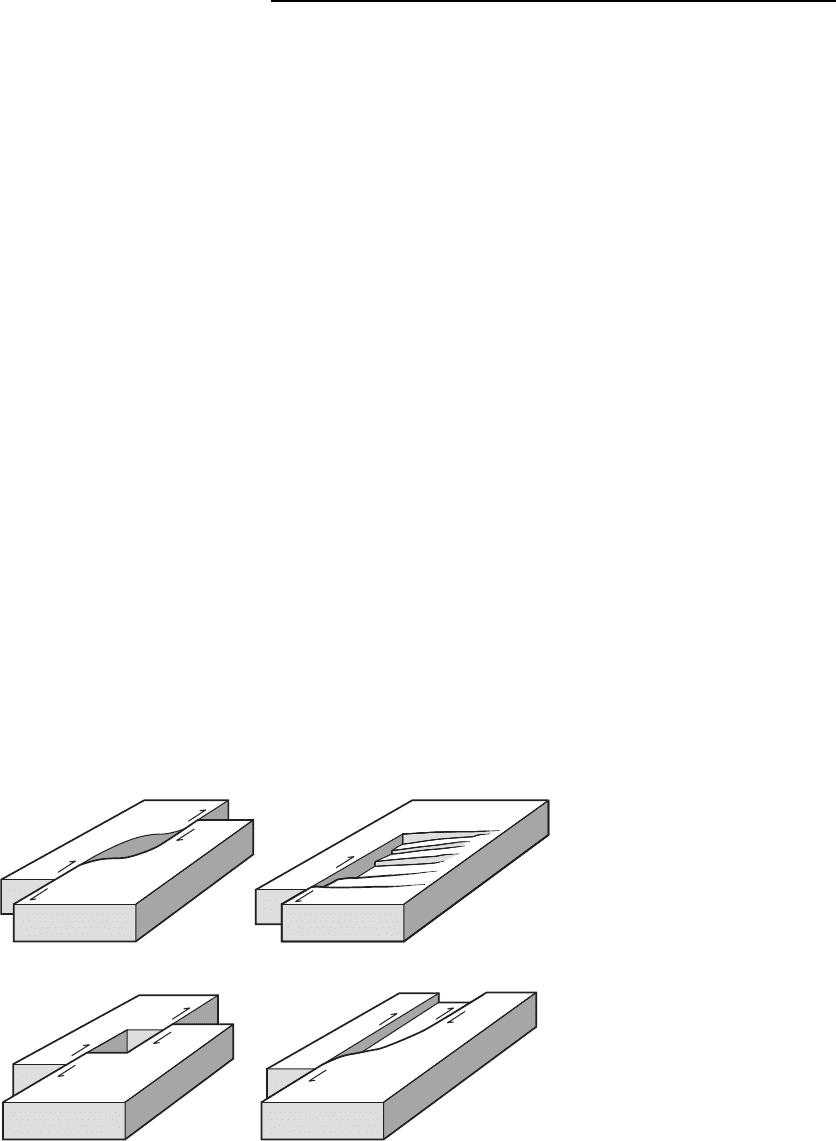

24.5.1 Strike-slip basins (Fig. 24.14)

Most basins in strike-slip belts are generally termed

transtensional basins and are formed by three main

mechanisms (Reading 1980). First, the overlap of two

separate faults can create regions of extension between

them known as pull-apart basins. Such basins are

typically rectangular or rhombic in plan with widths

and lengths of only a few kilometres or tens of kilo-

metres. They are unusually deep, especially compared

with rift basins. Second, where there is a branching of

faults a zone of extension exists between the two

branches forming a basin. Third, the curvature of a

single fault strand results in bends that are either

restraining bends (locally compressive) or releasing

bends (locally extensional): releasing bends form

elliptical zones of subsidence. Most strike-slip basins

are bounded by faults that extend deep into the crust;

‘thin-skinned’ strike-slip basins are an exception, as

the faulting affects only the upper part of the crust.

Strike-slip basins bounded by deep faults are rela-

tively small, usually in the range of a hundred to a

thousand square kilometres, and often contain thicker

successions than basins of similar size formed by other

mechanisms. Subsidence is usually rapid and several

kilometres of strata can accumulate in a few million

years (Allen & Allen 2005). Typically the margins are

sites of deposition of coarse facies (alluvial fans and

fan deltas) and these pass laterally over very short

distances to lacustrine sediments in continental set-

tings or marine deposits. In the stratigraphic record,

facies are very varied and show lateral facies changes

over short distances. ‘Thin-skinned’ strike-slip basins

are broader and relatively shallower (Royden 1985).

24.6 COMPLEX AND HYBRID BASINS

Not all basins fall into the simple categories outlined

above because they are the product of the interaction

of more than one tectonic regime. This most com-

monly occurs where there is a strike-slip component

to the motion at a convergent or divergent plate

boundary. A basin may therefore partly show the

characteristics of, say, a peripheral foreland but also

contain strong indicators of strike-slip movement.

Such situations exist because plate motions are com-

monly not simply orthogonal or parallel and examples

of both oblique convergence and oblique extension

between plates are common.

Basin formed at

releasing bend

Pull-apart

basin

Basin formed at

fault branch

Basin formed at

fault termination

Fig. 24.14 Basins may form by a

variety of mechanisms in strike-

slip settings: (a) a releasing bend,

(b) a fault termination, (c) a fault

offset (usually referred to as a pull-

apart basin) and (d) at a junction

between faults. Note that if the

relative motion of the faults were

reversed in each case the result

would be uplift instead of

subsidence.

392 Sedimentary Basins

24.7 THE RECORD OF TECTONICS IN

STRATIGRAPHY

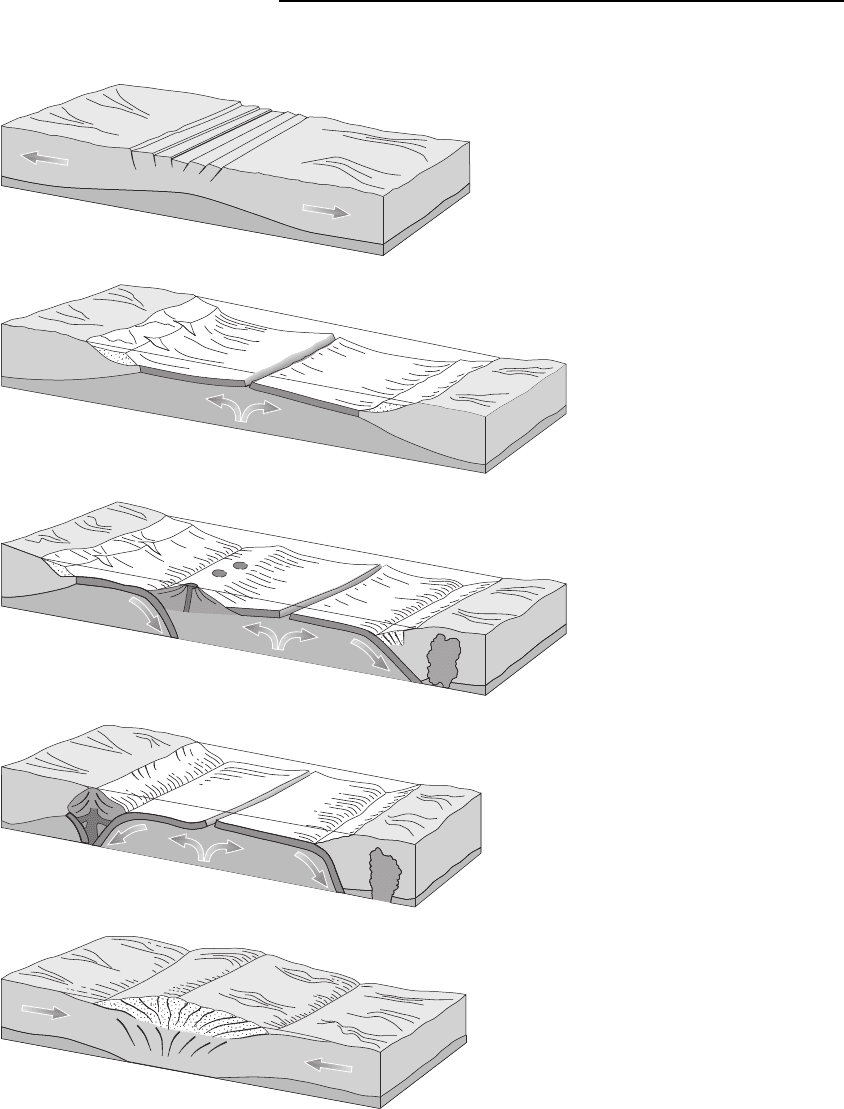

Tectonic forces act slowly on a human time scale but

in the context of geological time the surface of the

planet is in a continuous state of flux. Rift basins form

and evolve into proto-oceanic troughs and eventually

into ocean basins bordered by passive margins. After

a period of tens to hundreds of millions of years the

ocean basin starts to close with subduction zones

around the margins consuming oceanic crust. Final

closure of the ocean results in continental collision

and the formation of an orogenic belt. These patterns

of plate movement through time are known as the

Wilson Cycle (Fig. 24.15) (Wilson 1966). The whole

cycle starts again as the continent breaks up by

renewed rifting. This relatively straightforward

sequence of events may become complicated by obli-

que and strike-slip plate motion and over hundreds of

millions of years regions of the crust may experience a

succession of different tectonic settings, particularly

those areas adjacent to plate margins.

The record of changing tectonic setting is contained

within stratigraphy. For example, within the Wilson

Cycle, the rift basin deposits may be recognised by

river and lake deposits overlying the basement, evapor-

ites may mark the proto-oceanic trough stage, and a

thick succession of shallow-marine carbonate and clas-

tic deposits will record passive margin deposition. If this

passive margin subsequently becomes a site of subduc-

tion, arc-related volcanics will occur as the margin is

transformed into a forearc region of shallow-marine,

arc-derived sedimentation. Upon complete closure of

the ocean basin, loading by the orogenic belt may

then result in foreland flexure of this same area of the

crust, and the environment of deposition will become

one of deeper water facies. As the mountain belt rises,

more sediment will be shed into the foreland basin and

the stratigraphy will show a shallowing-up pattern.

The same principles of using the character of the

association of sediments to determine the tectonic set-

ting of deposition can be applied to any strata of any

age. An objective of sedimentary and stratigraphic

analysis of a succession of rocks is therefore to deter-

mine the type of basin that they were deposited in, and

then use changes in the sedimentary character as an

indicator of changing tectonic setting. In this way, a

history of plate movements through geological history

can be built up by combining the sedimentary and

stratigraphic analysis with data from palaeomagnetic

studies, which provide information about relative plate

motions through time, and palaeobiogeographical

information, which tells us about the distribution of

plants and animals. The geological history of an area is

now typically divided into stages that reflect different

phases in the regional tectonic development: for exam-

ple, in northeast America and northwest Europe,

Palaeozoic strata are divided into a succession of ma-

rine deposits that formed within and on the margins of

the Iapetus Ocean, sedimentary successions deposited

in trenches and arc-related basins as this ocean closed,

and, following the Caledonian orogeny, a thick

sequence of Devonian red beds deposited mainly in

extensional and strike-slip related basins within a

supercontinent land mass.

The frequency with which the tectonic setting may

change varies according to the position of a region

with respect to plate margins. It is only in the centre of

a stable continental area that the tectonic setting is

unchanging over long periods of geological time. For

example, the central part of the Australian continent

has not experienced the tectonic forces of plate mar-

gins for 400 million years and in the latter part of that

time a broad intracratonic basin, the Lake Eyre Basin,

has formed by very slow subsidence. In regions closer

to plate margins basins typically have a lifespan of a

few tens of millions of years. The backarc basins in the

West Pacific appear to be active for 20 million years

or so. In contrast the passive margins of the Atlantic

have been sites of sedimentation at the edges of the

continents for over 200 million years.

24.8 SEDIMENTARY BASIN ANALYSIS

A succession of sedimentary rocks can be considered

first in terms of the depositional environment of indi-

vidual beds or associations of beds (Chapters 7–10

and 12–17), and second in the context of changes

through time by the application of a time scale and

means of correlation of strata (Chapters 19–23). The

spatial distribution of depositional facies and varia-

tions in the environment of deposition through time

will depend upon the tectonic setting (see above), so a

comprehensive analysis of the sedimentology and

stratigraphy of an area must take place in the context

of the basin setting. Sedimentary basin analysis is

the aspect of geology that considers all the controls on

the accumulation of a succession of sedimentary

rocks to develop a model for the evolution of the

Sedimentary Basin Analysis 393

Rift basin

Ocean basin

Arc and trench formation

Ocean closure

Mountain belt

Fig. 24.15 The Wilson Cycle of

extension to form a rift basin

and ocean basin followed by basin

closure and formation of an oro-

genic belt. (Adapted from Wilson

1966.)

394 Sedimentary Basins

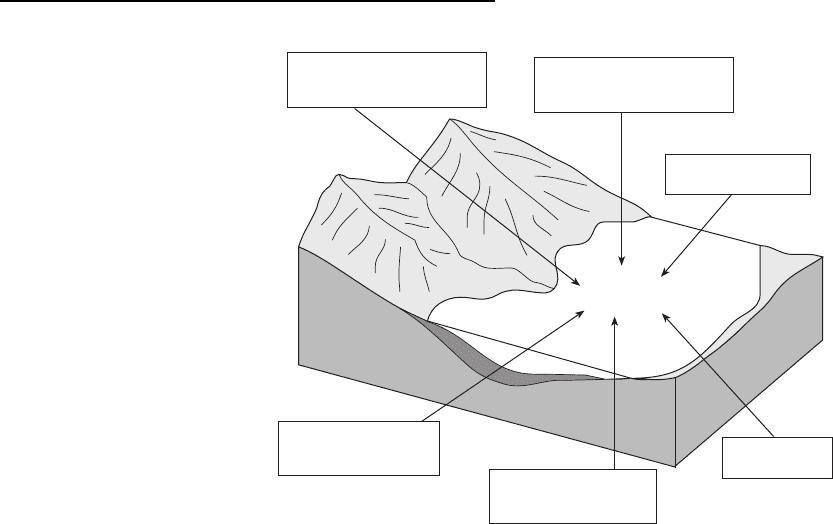

sedimentary basin as a whole (Fig. 24.16). A compre-

hensive summary of basin analysis is provided in texts

such as Allen & Allen (2005) and a brief introduction

is outlined below.

24.8.1 Structural analysis

The patterns of deformation within a sedimentary

succession provide information about the crustal

stresses that existed in the area during and after

deposition. Synsedimentary faults and folds are

evidence of tectonic activity during deposition: a

layer of strata may show structures (such as normal

faults) that indicate extension during sedimentation

or evidence of compressive forces (reverse faults or

folds) acting as the strata were accumulating. These

growth structures can be identified by the fact that

their occurrence is limited to a particular strati-

graphic unit within the succession. In general, exten-

sional settings such as rift basins can be distinguished

from basins formed under compressional regimes

(such as foreland basins) on the basis of the recogni-

tion of these syndepositional structures, although

local variations in stress commonly occur. Structural

features that affect the whole succession are evidence

of tectonic forces occurring after deposition in the

basin, but nevertheless provide information about

the plate tectonics history of the area.

24.8.2 Geophysical data

Information from seismic reflection surveys (22.2) pro-

vides subsurface structural data that can be used in the

structural analysis of a succession. Other geophysical

data are in the form of information about the mag-

netic properties of the rocks below the surface and

variations in the strength of the gravitational field in

the region of the basin. Magnetic surveys over an

area can indicate the nature of the rocks that lie at

depth below the sedimentary succession: in general

terms, oceanic crust retains a higher remnant mag-

netism than continental crust, allowing the crustal

substrate of a basin to be determined. The strength

of the Earth’s magnetic field at any point on the sur-

face depends on the density of the rocks below the

surface at that point. Gravity surveys can therefore

provide an indication of the thickness of sedimentary

strata present, as they are of lower density than

igneous or metamorphic rocks. Geophysical surveys

are therefore a useful way of distinguishing between

Fig. 24.16 Basin analysis tech-

niques.

Structural Analysis

tectonic setting

deformation during deposition

Geophysical data

basin structure

thickness of succession

Thermal History

burial history

Stratigraphic Analysis

age of rock units

correlation within basin

Sedimentological Analysis

sources of sediment

environments of deposition

Geohistory Analysis

subsidence history

Basin

Analysis

Sedimentary Basin Analysis 395

different basin types (e.g. extensional backarc basins are

floored by oceanic crust) and the amount of subsidence

that has occurred (basins in strike-slip setting com-

monly have very thick sedimentary successions).

24.8.3 Thermal history

Burial of sediments results in diagenetic changes

(18.2) that include the effects of increased tempera-

ture with burial depth. The temperature that a body of

sediment has been subjected to can be determined by

fission-track analysis (6.8) and by studying the vitri-

nite reflectance characteristics of organic matter pres-

ent in the sediment (3.6.2). The burial history of a

body of sediment can therefore be reconstructed using

these palaeothermometers, as they record the max-

imum temperature that the material has reached, and

this can be used to infer the depth to which it has been

buried. Combining these burial history data with the

age of the strata can provide information on the

history of subsidence in the basin and this can be

related to the basin setting.

24.8.4 Stratigraphic analysis

The relative or absolute dating of the strata in the

basin can be carried out using techniques described in

Chapters 19 to 23. These provide a time framework

for the basin history, indicating when the basin first

started to form (the age of the rocks that lie at the

bottom of the basin), and when sedimentation ceased

(the youngest strata preserved), as well as events in

between. The rate of sediment accumulation, that is,

the thickness of strata deposited between two datable

horizons, can be a characteristic indicator of basin

setting: for example, rift basin sediments will com-

monly accumulate at a faster rate than passive mar-

gin deposits. On a shorter time scale, changes in

sediment accumulation rate may reflect the relative

sea level (Chapter 23).

24.8.5 Sedimentological analysis

The nature and the distribution of sediment present

in a succession will reflect the basin setting. Three

main aspects of the sedimentological analysis of basins

can be considered: provenance studies, the distribution

of facies and palaeoenvironments, and the changes in

these through time during the basin evolution.

Provenance studies (5.4.1) are a key element of the

analysis of a basin, providing information about the

tectonic setting. Arc-related basins, such as backarc

and forearc basins, are most likely to contain volcanic

material derived from the magmatic arc. Rift basins in

continental crust contain material derived from the

surrounding cratonic area and are likely to include

clasts of plutonic igneous or metamorphic origin. Per-

ipheral foreland basins normally contain a high pro-

portion of reworked sedimentary rocks that have been

uplifted and subsequently eroded as part of the moun-

tain-building process. Changes in clast composition

through time can be used as an indicator of depth of

erosion in the hinterland source area and hence pro-

vide a record of the uplift and unroofing history of an

orogenic belt.

Once a stratigraphic framework for the basin suc-

cession has been established (24.8.4), the basin suc-

cession can be divided up into packages of strata, each

deposited during an interval of time. The distribution

of facies within an individual package provides a pic-

ture of the distribution of palaeoenvironments for that

time interval, and hence a palaeogeography can be

established. Different basin types can be expected to

show different patterns of sedimentation: for example,

a rift or strike-slip basin may be expected to have

coarse facies such as alluvial fans or fan-deltas at its

margins, a backarc basin would have an apron of

volcaniclastic deposits at one margin, and a passive

margin succession would be dominated by shallow-

marine clastic or carbonate facies.

The tectonic setting of the basin is a major factor

controlling the changes in the facies distributions and

palaeogeographical patterns through time. Peripheral

foreland basins and forearc basins both typically com-

prise deep-water facies in the lower part of the basin

succession, shallowing up to shallow-marine or con-

tinental deposits. In contrast, rifts and backarc basins

commonly show a progressive change from continen-

tal deposits formed in the early stage of rifting, fol-

lowed by shallow-marine and sometimes deeper-

marine facies. Changing palaeogeography within a

basin therefore reflects the tectonic evolution of both

the basin and the surrounding area.

24.8.6 Geohistory analysis

The quantitative study of the history of subsidence

and sedimentation in a basin is known as geohistory

396 Sedimentary Basins

analysis (Allen & Allen 2005). As sediment accumu-

lates, the material in the lower part of the succession

undergoes compaction (18.2.1), so the thickness of

each stratal unit decreases through time. The com-

paction effect varies considerably with different lithol-

ogies, with clay-rich sediments decreasing in volume

by up to 80% through time, whereas sandstones typi-

cally lose between 10 and 20% of their porosity as a

result of compaction. The history of subsidence in a

basin can be calculated by ‘decompacting’ the sedi-

mentary succession in a series of stages and by taking

into account the palaeobathymetry, the water

depth at which the sedimentation occurred deter-

mined from facies and palaeontological studies.

Further information about the burial history can

also be obtained from fission-track analysis (6.8) and

vitrinite reflectance studies (3.6.2 & 18.7.2), which

provide a measure of the thermal history of the strata.

Geohistory analysis is important in hydrocarbon

exploration because it provides information on the

porosity and permeability changes through time,

and also the thermal history of any part of the succes-

sion, which is critical to the generation of oil and gas

(18.7.3).

24.9 THE SEDIMENTARY RECORD

Sedimentology equips us with the tools to interpret rocks

in terms of processes and environments. These deposi-

tional environments are considered through geological

time in the context of stratigraphic principles and analy-

tical techniques. Sedimentological and stratigraphic

analysis of the rock record using the material exposed

at the surface, drilled and surveyed in the subsurface

provides us with the means to reconstruct the history of

the surface of the Earth as far as the data allow.

FURTHER READING

Allen, P.A. & Allen, J.R. (2005) Basin Analysis: Principles and

Applications (2nd edition). Blackwell Science, Oxford.

Busby, C. & Ingersoll, R.V. (Eds) (1995) Tectonics of Sedimen-

tary Basins. Blackwell Science, Oxford.

Einsele, G. (2000) Sedimentary Basins, Evolution, Facies and

Sediment Budget (2nd edition). Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

Ingersoll, R.V. (1988) Tectonics of sedimentary basins. Geo-

logical Association of America Bulletin, 100, 1704–1719.

Miall, A.D. (1999) Principles of Sedimentary Basin Analysis,

3rd edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

Further Reading 397