Fisher G. Between Empires. Arabs, Romans, and Sasanians in Late Antiquity

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

courts of an urban house’

118

) marks al-H

˙

ayyat as different. Further,

the method of dating to the establishment of the province of Arabia in

106 is not unusual, but the recognition of al-Mundhir in the dating

formula is a remarkable acceptance and acknowledgement of the

Jafnid leader’s prominence in the area. It is also not an isolated

case. To the north, approximately 20 kilometres east of Damascus,

an inscription was found in the vicinity of a structure at al-Burj and

close to the site of D

˙

umayr, originally thought by Brünnow and

Domaszewski to be a second-century Roman camp but which was

recently shown by Lenoir to date to the late antique period.

119

The

inscription, published by Waddington states that a tower was built by

Mundhir. He is described as ÆæŒ[Ø] and also takes the name

Flavius in the inscription.

120

Here, again, there is evidence for the

presence of the Jafnids in a settled area, close to Damascus, and the

inscription is also a rare attestation of direct Jafnid involvement in

building activity.

121

What can we make of this clear evidence for the presence of the

Jafnids and the people linked with them in both the H

˙

aurān and the

area around Damascus? In the first instance, it seems to lend some

support to the Muslim tradition, which places the Jafnids throughout

this region. A further indication of their presence here comes from

John of Ephesus, who tells of how Bostra became a convenient and

local target for disgruntled supporters of al-Mundhir after his arrest

in 581.

122

This, again, suggests a certain number of Jafnid supporters

in the region, roughly contemporary with the completion of the house

at al-H

˙

ayyat. It is certainly logical to expect the leadership and at least

some of the people who presumably made up the group to be found

in the same region, and we should not imagine that the Jafnids

could command any degree of local recognition without the consent

and support of the population on whom they were dependent for

manpower and political leverage. However, in the absence of archae-

ological evidence from Jabiya, or the identification of other sites

linked to the Jafnids in the H

˙

aurān, the speci fics for the presence

118

Foss, ‘Syria in transition’, 251.

119

M. Lenoir, ‘Dumayr, faux camp romain, vraie résidence palatiale’, Syria,76

(1996), 227–36, correcting Brünnow and Domaszewski, DPA, iii. 200; Genequand,

‘Some thoughts’, 79.

120

Wadd. 2562c.

121

Cf. Genequand, ‘Some thoughts’, 79.

122

Joh. Eph. HE 177 (3.3.42).

102 Empires, Clients, and Politics

and distribution of the wider group of people connected to the Jafnids

remains unclear.

It is also tempting from these two inscriptions to draw links

between the Jafnid presence and the expansion of settlement and

the economy in the region. It is obvious that the Jafnids cannot

have been the only factor, but their military and administrative role

as phylarchs, the health of the local sixth-century economy, and the

relative calm experienced by the H

˙

aurān during this period suggest

that they may have played some part.

123

Using archaeological data

showing the well-attested abandonment of Roman fortification sys-

tems throughout Jordan and southern Syria in the sixth century, as

well as data from regional archaeological surveys, J. Johns argued that

the ‘withdrawal’ of the Byzantine administration from the area, and

its administrative transfer to the Arab allies of the Empire, may have

relieved the local tax burden, allowing the community to retain its

agricultural surpluses and increasing the availability of disposable

wealth.

124

Johns’ argument is concerned with showing the prob-

lematic nature of traditional reasoning which finds a linear relation-

ship between the strength of the state, rural prosperity, and

population increase. His argument is thus designed to show that any

‘withdrawal’ of the state from southern Syria in fact boosted prosperity

and population, not the reverse.

125

The archaeological evidence for the

withdrawal of troops from the region is strong, and it is well under-

stood that phylarchs played, in general, some kind of administrative

role.

126

The place of the Jafnids in this is less clear, however, and it is

also hard to imagine that the government in Constantinople would be

willing to forgo tax revenue. The question remains open.

At the same time, however, the relative peace in the region (espe-

cially compared to the districts around Apamea and Antioch, further

north, which suffered repeatedly and more harshly from Sasanian

expeditions and natural disasters) favoured economic growth and

prosperity. The H

˙

aurān is also conspicuous for its lack of forti fica-

tions, specifically in the absence of fortified farmsteads or towers

123

Liebeschuetz, ‘Nomads, phylarchs and settlement’, 144.

124

J. Johns, ‘The longue durée: state and settlement strategies in southern Trans-

jordan across the Islamic centuries’ in E. L. Rogan and T. Tell (eds.), Village, Steppe

and State: The Social Origins of Modern Jordan (London, 1994), 1–31 at 7–10.

125

Ibid. 7–8, 30. Cf. Whittow, ‘Rome and the Jafnids’, 223–4.

126

For a recent survey of the evidence for troop withdrawal and the abandonment

of fortifications, see Fisher, ‘A new perspective on Rome’s desert frontier’.

Empires, Clients, and Politics 103

which are far more common further north.

127

Whether this peace can

be associated with the presence of the Jafnids will also remain open to

debate, and it may actually have more to do with the level of threat in

the south versus the north where natural invasion routes followed the

Euphrates, but not the road across the desert via Palmyra. It is,

however (as Liebeschuetz indeed suggests), reasonable to see some

kind of link between regional security and the extensions of settle-

ment, as well as the lengthy and predominantly stable relationship

between the Jafnids and the Empire.

In my opinion, the most likely link between prosperity and the

Jafnids is a financial one.

128

The presence of the al-Burj inscription

and reports of the tower (long-since demolished) clearly show that

the Jafnids were spending money in the region.

129

Construction and

the installation of inscriptions required funds, presumably derived

either from subsidy or from other sources of income. Ancient writers

describe the lucrative results of raiding, and it is likely that some of

this money found its way into local prestige projects as well as private

coffers and the broader economy.

130

It is possible that the Jafnids also

collected some form of local taxation to their benefit; as we saw above,

the Nas

rids were reported to have received the right to do so from the

Sasanians, and the tradition of tax from pasture land appears as a

factor in the ‘strata’ argument between al-H

˙

ārith and al-Mundhir the

Nas

rid in 537.

131

It is possible, then, that involvement with the local

economy in the H

˙

aurān or its environs may have revolved around the

influx of cash from stipendiary or tax sources which then found

material expression.

132

The presence of such wealth was also likely

to have not only stimulated the local economy, but also to have

provided increased prosperity in a cyclical fashion to those who

participated in it. The tower at al-Burj, for example, was therefore

not simply a monument to the activity of an elite member of society,

127

Foss, ‘Syria in transition’, 252; Tate, Campagnes,48–51.

128

Cf. Whittow, ‘Rome and the Jafnids’, 224.

129

Liebeschuetz, ‘Nomads, phylarchs and settlement’, 145.

130

e.g. Malalas, Chron. 447, on 20,000 slaves taken as booty in the Samaritan

revolt, and then sold in ‘Persia and India’ (c.528); cf. Josh. Styl. Chron. 52, on 18,500

prisoners taken by the Nas

rid al-Nu mān in a raiding expedition in c.502.

131

Proc. BP 2.1.8.

132

Liebeschuetz, ‘Nomads, phylarchs and settlement’, 143; Whittow, ‘Rome and

the Jafnids’, 224.

104 Empires, Clients, and Politics

but also represented the public disposition of money and the hiring of

workmen and artisans. At al-H

˙

ayyat, the house was not built by al-

Mundhir, but it is particularly interesting that Seos insists on the fact

that he and his son Olbanos paid for the construction themselves.

133

The affiliation of Seos is unknown, but this conspicuous, public dis-

play of local wealth is what we might expect to see from wealthy

members of society under the prosperous economic conditions of the

time, and the presence of al-Mundhir’s name on the inscription again

connects him to precisely that.

The construction of the al-Burj tower is a rare example of a so-

called Ghassānid building, in actuality a Jafnid building, but its

inscription, ostentatiously demonstrating the name of its founder,

shows it to be the type of project that was the traditional preserve of

local wealthy individuals. Al-Mundhir was engaging in normal elite

activity, suggesting that he was (or wished to give the impression

that he was) very much part of the local community landscape. This

activity also built on earlier acclamations, such as that from Ne-

māra. In its essence, the Nem āra inscription was a celebration of the

high-profile position of Imruʾ l-Qays, and the heart of this message

is preserved elsewhere, not only at al-Burj and al-H

˙

ayyat but also in

the sixth-century inscription commemorating Abū-Karib, from

Sammāʾ (Ch. 2 n. 71), the mosaics at Nitl (Ch. 2 n. 65), the

acclamation to al-H

˙

ārith at Qas

ral-H

˙

ayr (Ch. 2 n. 97) and the

al-Mundhir building at Res

āfa (Ch. 2 n. 74). Nemāra was ‘inside’

the Roman periphery, but it was a self-declared monument whose

genesis laid claim less to local involvement and more to the wide-

ranging abilities of Imruʾ l-Qays away from the settled lands of the

Roman Empire. Two hundred years later, the inscriptions of

Sammāʾ,Nitl,H

˙

ayyat, and al-Burj, in particular, contain an addi-

tional element: a greater level of integration, specifically in terms of

their imitation of the ways in which Roman elites were typically

celebrated on inscriptions.

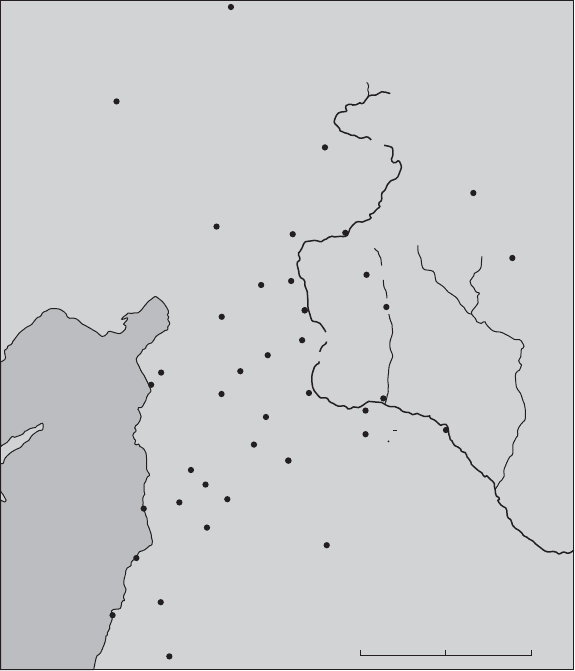

In this context, it is worth mentioning here three additional and well-

known inscriptions. At Anasartha, nearChalcis in the north of Syria (see

Map 6), inscriptions on two martyria dating to the fifth century raise the

question of non-Jafnid Arab involvement in building in areas of sig-

nificant Roman settlement. The first is a martyrion to St Thomas, dated

133

Genequand, ‘Some thoughts’, 79.

Empires, Clients, and Politics 105

to 425/6 and dedicated by a certain Mabia/Mavia.

134

Fanciful notions of

a link between this individual and the famous queen of the same name

have been suggested on numerous occasions.

135

The placement of the

Sebaste

Caesarea

Melitene

Germanicia

Nisus

Samosata

Amida

Mardine

Edessa

Carrhae

Zeugma

Europos

Hieropolis

Bathnae

Beroea

Chalcis

Anasartha

Androna

Seriane

Palmyra

0 200km

Larissa

Antioch

Cyrrhus

Doliche

Seleucia

Epiphania

Salaminias

Raphanaea

Emesa

Tripolis

Heliopolis

Damascus

Berytus

Tartus

Barbalissos

Callinicum

Sura

Resafa

Zenobia

MEDITERRANEAN

SEA

RIVER EUPHRATES

Map 6. Northern Syria.

134

The text is published by R. Mouterde, Le limes de Chalcis: organisation de la

steppe en haute Syrie romaine: documents aériens et épigraphiques, 2 vols (Paris, 1945),

i. 194–5.

135

Mouterde, Limes, raised the possibility of a descendant of Mavia; Shahid,

Fourth Century, 222–4, believes it to be the queen herself. See the discussion in

D. Feissel, ‘Les martyria d’Anasartha’, in V. Déroche (ed.), Mélanges Gilbert Dagron,

T&M 14 (Paris, 2002), 201–20, at 205–9.

106 Empires, Clients, and Politics

martyrion outside the walls of the city raises parallels with other extra-

mural constructions, such as the al-Mundhir building at Res

āfa, and

their potential place in regulating the relationship between nomads and

settlers.

136

However, there is no indication that Mavia was a phylarch

and any argument in favour of ‘nomads’ rests insecurely on the fact that

the name is Arabic in origin; all that can be safely said is that a person

with an Arabic name was the dedicator of this martyrion.

137

The second martyrion is more interesting. Built during the same

period, it celebrates a clarissimus ([ºÆ]æÆ) Silvanus as its

dedicator, enigmatically described as having power K ¯æE.

138

The text, which presents numerous significant difficulties of inter-

pretation, contains a variety of Homeric ‘echoes’ and K ¯æE is

taken by Feissel, through analogy to the Odyssey, as a reference to the

Arabs.

139

The martyrion is also apparently dedicated to Silvanus’

recently deceased daughter, described as a young wife of a phylarch.

From this, Silvanus has been variously described as a Roman officer

or even a phylarch himself, but there is no evidence to support such a

claim.

140

What the inscription does show, in the link between the

family of a clarissimus and a phylarch, is a different level of the

connections between phylarchs and the local elite of the sort which

finds a parallel at al-H

˙

ayyat.

Finally, the third inscription, from a martyrion of St John erected at

H

˙

arrān, is dedicated in its inscription in Greek and Arabic by an

unknown phylarch named Sharah

˙

īl(Ææź), who is commemo-

rated as the one who paid (ŒØ) for it (Ææź ƺı

çºÆæå[] ŒØ e Ææ[æØ] F ±ªı øı).

141

Like the

other inscriptions with an Arabic component referred to here, this

example will be discussed in greater detail in the following chapter.

Here I wish simply to point out that, in contrast to the example above

136

Mouterde, Limes, 195.

137

Cf. Liebeschuetz, ‘ Nomads, phylarchs and settlement’, 144.

138

IGLS 297.

139

Feissel, ‘Les martyria d’Anasartha’, 213–14.

140

Mouterde, Limes, 193; Jalabert and Mouterde in IGLS ii. 168–70, consider him

to be a dux Arabiae; Feissel, ‘Les martyria d’Anasartha’, 213: ‘Titulaire d’une dignité

romaine, Silvanos n’était cependant pas un fonctionnaire impérial: son autorité sur les

Arabes (appelés en style homérique ...), qui plus est une autorité perpétuelle, ne peut

être que celle d’un chef indigène, autrement dit un phylarque arabe.’

141

Wadd. 2464. See too Sartre, Trois études, 177; Genequand, ‘Some thoughts’, 80;

E. Littmann, ‘Osservazioni sulle iscrizioni di Harran e di Zebed’, Revista degli studi

orientali, 4 (1911), 193–98, and the discussion of this inscription in Ch. 4.

Empires, Clients, and Politics 107

where the provenance of the phylarch was unknown, both the name

and language on the H

˙

arrān inscription clearly favour identification

with an Arab phylarch, demonstrating unambiguously an engage-

ment in an elite Roman activity by an Arab close to the main

recognised sphere of Jafnid activity.

Of these three inscriptions, the latter two provide the best evidence for

additional links between ‘Roman’ elites, phylarchs, and commemorative

or acclamative inscriptions, and suggest that the presence of the Jafnids

on inscriptions in the H

˙

aurān should be placed within the context of a

wider pattern of integration which had been going on for some time.

Either as benefactors of inscriptions or appearing as third parties, late

antique Arab potentates, characterised in the majority by the Jafnids,

were in essence taking the role of late antique Roman elites. With the

construction of a tower at al-Burj, celebrated by a dedicatory Greek

building inscription, al-Mundhir was firmly linking himself, as he had at

Res

āfa, with the practices of a specific and highly visible sector of society.

SETTLEMENT AND SEDENTARISATION?

A key question is the extent to which the Jafnids were connected to

settlement patterns in the regions where they were active. Of parti-

cular interest is their possible connection to the processes of settle-

ment for any nomads and semi-nomads who may have fallen under

their control in the steppe and desert regions of Syria and Jordan.

Sedentarisation is an ancient and ongoing process, but it is dif ficult to

detect in ancient sources; the close relationship between nomads,

semi-nomads, and settlers obscures its specifics, especially since the

literary evidence prefers to emphasise extremes by highlighting raids,

brigandage, and other minor disruptions.

142

Nevertheless, the on-

going debate continues to demonstrate that settlers (those who

chose to spend the majority of their time in a single domicile in either

urban or rural settings) and nomads were closely connected, even

during episodes of animosity and even while they both occupied

‘settled’ and ‘nomadic’ regions.

143

It is also now well understood

142

E. B. Banning, ‘De Bello Paceque:AReplytoParker’, BASOR, 265 (1987), 52–4, at 53.

143

For which (with specific reference to this period) see Donner, ‘The role of

nomads’,73–4; also, the lengthy debate in the Bulletin of the American Schools of

108 Empires, Clients, and Politics

that nomads did not follow pastoralism exclusively, but had distinct

ties to economic activities which are normally associated with settled

populations. A small number of ancient graffiti from the desert, for

example, discuss opportunistic crop-sowing carried out by nomads,

and this activity is also known from other sources.

144

Despite such promising information, attempts to demonstrate the

integration of settled and nomadic groups in the H

˙

aurān have been

largely inconclusive. For example, Macdonald has convincingly shown

that Villeneuve’s argument for a connection between the increase in the

settled population of the H

˙

aurān in the early Roman period, and the

sedentarisation of nomads, was based on tenuous evidence, since it

depended on accepting the very contestable premise that the evidence

for tribal names in the region reflected the presence of nomads.

145

Macdonald has, in fact, shown that the opposite case might be true,

arguing convincingly that the authors of the ‘Safaitic’ graffiti in question

were neither sedentary nor lived in the settled areas south of Damascus,

as has sometimes been claimed, and, in fact, probably had much more to

Oriental Research,esp.E.B.Banning,‘Peasants, pastoralists, and the pax romana’,

BASOR, 261 (1986), 25–50, and the reply from S. T. Parker, ‘Peasants, pastoralists and

pax romana: a different view’, BASOR, 265 (1987), 35–51, and Banning, ‘De Bello

Paceque’ (n. 114); also P. Mayerson, ‘Saracens and Romans, 71–9; D. Graf, ‘Rome and

the Saracens: reassessing the nomadic menace’, in T. Fahd (ed.), L’Arabie préislamique

et son environnement historique et culturel. Actes du Colloque de Strasbourg, 24–27 juin

1987 (Leiden, 1989), 341–400; and B. Shaw, ‘Fear and loathing: the nomadic menace in

Roman Africa’,inC.M.Wells(ed.),Roman Africa: The Vanier Lectures, 1980 (Ottawa,

1982), 29–50; G. Tate, ‘Le problème de la défense et du peuplement de la steppe et du

désert, dans le nord de la Syrie, entre la chute de Palmyre et la règne de Justinien’, Ann.

Arch. Syr., 42 (1996), 331–5, at 334; Khazanov, Nomads and the Outside World,1–4.

144

M. C. A. Macdonald, ‘Nomads and the H

˙

awrān in the late Hellenistic and

Roman periods: a reassessment of the epigraphic evidence’, Syria, 70 (1993), 303–413,

at 316–17; also, A. M. Khazanov, ‘Nomads in the history of the sedentary world’,in

A. M. Khazanov and A. Wink (eds.), Nomads in the Sedentary World (Richmond,

Surrey, 2001), 1–24, at 1–2; S. A. Rosen and G. Avni, ‘The edge of empire: the

archaeology of pastoral nomads in the southern Negev highlands in Late Antiquity’,

BA, 56 (1993), 189–99, at 196–7.

145

F. Villeneuve, ‘Citadins, villageois, nomades: le cas de la Provincia Arabia (II

e

–

IV

e

siècles ap. J.-C.)’, Dialogues d’histoire ancienne, 15/1 (1989), 119–140, at 134–5;

Macdonald, ‘Nomads and the H

˙

awrān’,315–16; cf. M. Sartre, ‘Tribus et clans dans le

Hawran antique’, Syria, 59 (1982), 77–97, at 88–9. Cf. too also problematically

H. I. Macadam, ‘Epigraphy and village life in southern Syria during the Roman and

early Byzantine periods’, Berytus, 31 (1983), 103–15, esp. 111: ‘these [areas where tribal

inscriptions are found] are the upland areas on the fringes of the desert, and the areas

which would be a natural choice of Bedouin in the transitory stage from nomadism to

urbanization.’

Empires, Clients, and Politics 109

do with the desert than the fertile agricultural lands of the H

˙

aurāneven

while they interacted with the population of the region.

146

Challenges remain in identifying processes of nomadic settlement

in Late Antiquity, as they do for the earlier periods discussed by

Macdonald, and it is very unclear to what degree any of the Arab

groups who were probably at the fringes of the Roman Empire

‘settled’. Shahid is a vocal proponent of the position that the Jafnids

and Ghassān completely sedentarised in Late Antiquity, but there is

absolutely no evidence for such a claim, and it is also necessary to

point out that sedentarisation can be a long-term process, and neither

irreversible, nor fixed, nor quick.

147

The simple opposite—that the

Jafnids and their ‘group’ remained wholly nomads—is also unlikely.

In fact, the most reasonable demographic description is that any

group of people at the edges of Rome’s desert frontier would have

included a mix of settled, nomadic, and semi-nomadic strata, with the

Jafnids working to extend their power and influence over the pastor-

alists of the steppe and desert regions.

148

There was of course clear

146

Macdonald, ‘Nomads and the H

˙

awrān’, 311, esp. 322: ‘the content and dis-

tribution of the Safaitic inscriptions point inescapably to the conclusion that their

authors were nomads. I can find no evidence to support the view that they lived

among the sedentaries on Jabal H

˙

awrān, even for part of the year, indeed all the

information these texts provide suggests the opposite.’ This is a strong rejection of

both J. T. Milik, ‘La tribu des Bani Amrat en Jordanie de l’époque grecque et romaine’,

ADAJ, 24 (1980), 41–54, and M. Sartre, L’Orient romain: provinces et sociétés provin-

ciales Méditerranée orientale d’Auguste aux Sévères (31 avant J.-C.–235 après J.-C.)

(Paris, 1991), esp. 333; see as well id., ‘Transhumance, économie et société de

montagne en Syrie du sud’, Ann. Arch. Syr., 41 (1997), 75–86.

147

Cf. once more Shahid, Sixth Century, ii/1, esp. 1–20, who considers Ghassānto

be completely sedentarised following (1) ‘the time [that] they crossed the Byzantine

frontier’. Shahid writes (1): ‘when the Arab poets of pre-Islamic times and later

authors identified the Ghassānid lifestyle as sedentary and not nomadic, they gave a

truthful description of it.’ Also Sixth Century ii/1, 136–40, where he criticises Fow-

den’s Barbarian Plain for suggesting that some of Ghassān may have been nomads.

For processes of sedentarisation, see, generally, Khazanov, Nomads and the Outside

World, 199–201; also, P. C. Salzman, ‘Introduction: processes of sedentarisation as

adaptation and response’ in When Nomads Settle,1–20, at 11–14; in the same volume,

R. Bulliet, ‘Sedentarisation of nomads in the seventh century: the Arabs of Basra and

Kufa’,35–47; W. G. Dalton, ‘Some considerations in the sedentarisation of nomads:

the Libyan case’, in Salzman and Galaty (eds.), Nomads in a Changing World, 139–64,

esp. 144–61. These articles provide valuable perspectives on sedentarisation as a long-

term process.

148

Cf. Genequand, ‘Some thoughts’, 78: ‘It is important to remember that all the

territory under Jafnid control was not only settled by people ...whether they were

sedentary, semi-nomads or nomads, but also by other tribes ...these independent

tribes were simply members of the confederation under a general Jafnid leadership.’

110 Empires, Clients, and Politics

motivation for the Jafnids to ensure that whatever manpower existed

in the desert came under their control, and not under that of the

Nas

rids. One particular problem in Shahid’s position (‘there is no

doubt about their sedentary nature’

149

) is that he does not mention

the possibility that different sections of the population of the peoples

led by the Jafnids would have had very different motivations for either

sedentarising or choosing an alternative path. In this scenario, the

most likely section to settle would be the Jafnids themselves, and

those most closely connected to them, as a result of their close

relationship with the Empire. Certainly the epigraphic evidence

from al-H

˙

ayyat and al-Burj leads naturally to an argument for the

sedentarisation of the elite, derived from several logical propositions.

First, that nomads do not tend to build structures of relative perma-

nence, favouring more ephemeral structures better suited to their

specific and seasonal, temporary needs; secondly, that an acknowl-

edgement of a nomadic leader in the H

˙

aurān makes less sense than to

posit one who identified more clearly with a settled lifestyle; thirdly,

that the use of Greek inscriptions suggests a desire to be associated

with the local settled population; and fourthly, that the location of the

two inscriptions favours an argument for activity within a settled area.

Of course, there is no proof of Jafnid settlement; all that can be said

is that the incentive to settle would be felt more keenly by the elites,

who stood to gain from closer association with the villages, cities, and

towns of the Empire. Furthermore, if it can be said that the Jafnid elite

were the most likely to settle, the situation for the balance of the

people under their control is very murky indeed. The indications

from John of Ephesus that they were present in some number in

the general region of the H

˙

aurān does not provide any clues as to

their mode of life, and details of the large number of settlements

connected to the Jafnids by later authors such as Hamza are very

much open to debate. In a different article, Villeneuve once again

suggested that population increase in the H

˙

aurān may be linked to the

settlement of nomads in Late Antiquity, as elements of Arab groups

moving north from Arabia chose to remain in the area.

150

The

objection to his argument based on the existence of tribal names

149

Shahid, Sixth Century, ii/1, 140.

150

Villeneuve, ‘L’économie rurale’, 117, who asks: ‘comment les villageois ont-ils

pu s’accommoder de cette poussée des nomades à l’époque byzantine?’; see too

Macdonald, ‘Nomads and the H

˙

awrān’, 315.

Empires, Clients, and Politics 111