Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

World Trade Organization (WTO)

activists, and organic farmers were among those who filled

the streets. They held teach-ins, workshops, and peaceful

marches with thousands of participants (sometimes de-

scribed as “turtles and teamsters"), but what got headline

coverage was civil disobedience including blocking streets,

unfurling banners from atop giant construction cranes, and,

for a few of the most radical anarchists, breaking windows,

setting fires in dumpsters, and looting stores. These destruc-

tive acts were condemned by mainstream groups, but got

most of the press anyway.

Unprepared for such a massive protest movement, the

police reacted erratically. Ordered to avoid confrontation on

the first day of the protests, the police stood by while a small

contingent of black-hooded anarchists smashed windows

and vandalized property. The next day, stung by criticism

of being too soft, the police used excessive force to clear the

streets, firing

rubber

bullets and tear gas indiscriminately,

spraying innocent bystanders with pepper spray, and club-

bing nonviolent groups engaged in passive sit-ins. The mayor

declared a civil emergency and a 24–hour curfew in the area

around the Civic Center. Eventually, the National Guard

was called in to assist the thousands of city police. As often

happens in confrontations, positions harden and violence

begets more violence.

Most of the people protesting in Seattle agreed that

the current WTO represents a threat to democracy, quality

of life,

environmental health

, social justice, labor rights,

and national sovereignty. Underneath these complaints is a

broader unease about trends towards globalization and the

power of transnational corporations. Although the diverse

band of protestors shared many concerns, many disagreed

about the best solutions to these problems and how to achieve

them. While many claimed they wanted to shut down the

WTO, others actually want a stronger trade organization

that can enforce rules to protect workers, environmental

quality, and

endangered species

.

In the end, the delegates adjourned without agreement

on an agenda for the “Millennium Round” of the WTO.

Developing countries, such as Malaysia, Brazil, Egypt, and

India, refused to allow labor conditions into the debate.

Major agricultural exporters such as the United States, Can-

ada, Argentina, and

Australia

, continued to demand an

end to crop subsidies and protective policies. Japan and the

European Union

(EU), on the other hand, maintain that

they have a right to preserve small, family farms, rural life-

styles, and traditional methods of food production against

foreign competition. Developing countries insist that protec-

tion of their

environment

and

wildlife

is no one’s business

but their own.

Following Seattle in 1999, activists have demonstrated

against the effects of globalization at a number of world

governance meetings. The most violent of these occurred in

1537

July 2001, when 100,000 protestors converged on a meeting

of the Group of Eight Industrialized Nations in Genoa,

Italy. As was the case in Seattle, the vast majority of the

demonstrators were peaceful and non-violent, but a small

group of radicals attacked police and vandalized property.

The police responded with what many observers considered

excessive force, killing one man and injuring hundreds of

others. Outrage at police behavior spread across Europe

as live television showed unprovoked attacks on peaceful

marchers and innocent bystanders.

In the aftermath of Genoa, both protestors and gov-

ernment officials began to re-examine their strategies for

future meetings. Leaders of many community groups ques-

tion whether they should take part in mass demonstrations,

because of both the personal danger and the negative image

resulting from association with marauding vandals. They

began to reflect on other ways to carry out their goals while

avoiding the violence that marred previous demonstrations.

Government officials announced that future meetings would

be held in remote, inaccessible locations that limit public

participation. The 2001 meeting of the WTO, for example,

was held in Qatar, an authoritarian country that strictly

forbids any form of public demonstration. Those who

weren’t official delegates to the meeting weren’t even allowed

into the country, perpetuating the image of the WTO as a

secretive and high-handed organization.

While the location and tactics of the debate about

globalization has changed, the basic problems remain. As

Renato Ruggiero, the former director-general of the WTO

once said, “We are no longer writing the rules of interaction

among separate national economies. We are writing the

constitution of a single global economy.” The politicians and

transnational corporations who currently control much of

direction of global governance dismiss their critics as an

irrelevant collection of environmental extremists and bleed-

ing-heart social activists who know nothing about economics

or practical politics. On the other hand, even World Bank

president, James D. Wolfensohn admits that “at the level

of people, globalization isn’t working.” We clearly need a

way to engage governments and others in a dialogue on how

we will organize global trade in an increasingly intercon-

nected world.

Interestingly, the organizational power of protest

groups in Seattle and elsewhere shows the growing interna-

tionalism of social movements and grass-roots organizations.

Internet technology, the declining cost of travel, and rising

educational levels have dramatically extended their capacity

to both think and act globally. Those who protest globaliza-

tion and argue for traditional, time-honored ways of doing

things are themselves using the technology and power of

global organization. Somehow we need to find a way to get

beyond “No.” How do we want to govern ourselves? How

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

World Wildlife Fund

will we respect local autonomy and culture, and still enjoy

the benefits that come from the increased flow of goods and

services across international borders?

[William P. Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Gallagher, Peter. Guide to the WTO and Developing Countries. Boston, MA:

Kluwer Law International, 2000.

Howse, Robert. “Eyes Wide Shut in Seattle: The Legitimacy of the World

Trade Organization.” In The Legitimacy of International Institutions. United

Nations University Press, 2000.

Von Moltke, Konrad. Trade and the Environment: The Linkages and the

Politics. Winnipeg, Canada: International Institute for Sustainable Develop-

ment, 2000.

P

ERIODICALS

Cohn, Marjorie, ed. “Human Rights and Wrongs.” Guild Practitioner 57

(2000): 121.

Kovel, Joel. “Beyond the World Trade Organization.” Synthesis/Regenera-

tion 21 (2000): 6–9.

O

THER

“A Citizen’s Guide to the World Trade Organization: Everything You

need to know to Fight for Fair Trade.” Working group on the WTO. July

1997 [cited July 9, 2002]. <http://www.citizen.org>.

Anderson, Sarah, and John Cavanagh. “The World Trade Organization”

Foreign Policy in Focus. The Institute for Policy Studies.1997 [cited July 9,

2002]. <http://www.foreignpolicy-infocus.org/briefs/vol2/

v2n14wto.html>.

Murphy, Sophia. “Managing the Invisible Hand: Markets, Farmers and

International Trade” 2002. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. [cited

July 9, 2002]. <http://www.tradeobservatory.org>.

Seattle Weekly Editors. “Answering WTO’s Big Questions: In a Nutshell,

What was WTO Seattle?” Seattle Weekly. August 3–9, 2000 [cited July 9,

2002]. <http://www.seattleweekly.com/features/0031/news-

editors.shtml>.

World Wildlife Fund

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) is an international

con-

servation

organization founded in 1961, and known inter-

nationally as the World Wide Fund for Nature. The World

Wildlife Fund acts with other U.S. organizations in a net-

work to conserve the natural

environment

and ecological

processes essential to life. Particular attention is paid to

endangered species

and to natural habitats important for

human welfare. In hundreds of projects conducted or sup-

ported around the world, WWF helps protect endangered

wildlife and habitats and helps protect the earth’s

biodiver-

sity

through fieldwork, scientific research, institutional de-

velopment, wildlife trade monitoring, public policy initia-

tives, technical assistance and training,

environmental

education

, and communications.

WWF has articulated nine goals that guide its work:

1538

O

to protect habitat

O

to protect individual

species

O

to promote ecologically sound development

O

to support scientific investigation

O

to promote education in developing countries

O

to provide training for local wildlife professionals

O

to encourage self-sufficiency in developing countries

O

to monitor international wildlife trade

O

to influence public opinion and the policies of governments

and private institutions

Toward these goals, WWF monitors international

trade in wild plants and animals through its TRAFFIC

(Trade Records Analysis of Flora and

Fauna

in Commerce)

program, part of an international network in cooperation

with

IUCN—The World Conservation Union

. TRAFFIC

focuses on the trade regulations of the

Convention on Inter-

national Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna

and Flora

(CITES), tracking and reporting on traded wild-

life species; helping governments comply with CITES provi-

sions; developing training materials and enforcement tools

for wildlife-trade enforcement officers; pressing for stronger

enforcement under national wildlife trade laws; and seeking

protection for newly threatened species.

Other recent WWF projects have included programs

to save the African elephant, especially through banning

ivory imports under CITES legislation. The organization

also has undertaken projects to preserve tropical rain forests;

to identify conservation priorities in the earth’s biogeograph-

ical regions; to halt overexploitation of renewable resources;

and to create new parks and wildlife preserves to conserve

species before they become endangered or threatened. Based

on WWF’s conservation efforts, The Charles Darwin Foun-

dation for the Galapagos Islands awarded WWF an institu-

tional seat on their Board of Directors.

WWF also funded a study of more than 2,000 projects

or activities reviewed by the U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service

between 1986 and 1991. The study found that only 18 of

these projects were blocked or withdrawn because of detri-

mental effects to human populations. The study also showed

that the Northwest lost more timber jobs to automation of

timber cutting and milling, increased exports of raw logs,

and a shift of the industry to the Southeastern United States,

than it may lose from the listing of the

northern spotted

owl

(Strix occidentalis caurina) as an endangered species.

WWF has been credited with saving some 30 endan-

gered animal species from

extinction

, most notably the

gi-

ant panda

, which has become the group’s logo. Using

Geo-

graphic Information Systems

satellite technology, WWF

has identified regions where conservation of distinct animal

and plant species are most needed. By overlaying these areas

with existing parks and projects, WWF is able to see where

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Charles Frederick Wurster

it needs to concentrate conservation programs. The organi-

zation publishes a wide variety of materials, including the

periodicals WWF Letter, TRAFFIC, and Tropical Forest Con-

servation. Booklets produced include “Speaker and News

Media Sourcebook: A Guide to Experts in Domestic and

International Environmental Issues,” for news media, poli-

cymakers, and organizations. Educational materials, research

papers, and books jointly published include The Gaia Atlas

of Future Worlds: Challenge and Opportunity in an Age of

Change (by Norman Myers); Options for Conservation: The

Different Roles of Nongovernmental Conservation Organiza-

tions (by Sarah Fitzgerald); WWF Atlas of the Environment

(By Geoffrey Lean, et al.); and The Official World Wildlife

Fund Guide to Endangered Species of North America. In 1996

the WWF produced a nationwide environmental program,

Windows on the Wild, for educators concerning the chal-

lenges of global conservation.

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

World Wildlife Fund-U.S., 1250 12th Street, NW, Washington, D.C.

USA 20037, <http://www.worldwildlife.org>

Worldwatch Institute

Worldwatch Institute, a research organization based in

Washington, D.C., compiles and publishes information on

worldwide environmental problems; it also suggests solutions

and alternative courses of action. The Institute was founded

in 1975 by

Lester R. Brown

, with financial assistance from

the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. Brown is now its president

and director of research; chairman of the board is former

Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman. Membership is

$25 annually. The fee helps support the Institute’s research

and publications, which members receive, but there are no

avenues for membership participation within the Institute.

The Institute has published the State of the World

report annually since 1984; sales in recent years reached

$200,000. It is issued in 26 languages and is used as a

textbook in over 600 colleges in the United states alone.

The publication examines such topics as global warming,

water and

air quality

, and the environmental impact of

social policies. In 1990, State of the World was produced as

a 10-part series on public television, a joint venture with the

producers of Nova. The 1992 edition describes “a planet at

risk” and warned that “the policy decisions we make during

this decade will determine” the quality of life for

future

generations

.

Six to eight other Worldwatch papers are published

each year, and over a hundred monographs have been issued

1539

on specific subjects. Worldwatch magazine is published in

several languages, and the Environmental Alert series targets

particular environmental issues.

[Lewis G. Regenstein and Amy Strumolo]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Worldwatch Institute, 1776 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Washington, D.C.

USA 20036-1904 (202) 452-1999, Fax: (202) 296-7365, Email:

worldwatch@worldwatch.org, <http://www.worldwatch.org>

WTO

see

World Trade Organization

Charles Frederick Wurster (1930 – )

American environmental scientist

Dr. Charles Wurster, a founding trustee of

Environmental

Defense

(formerly the Environmental Defense Fund, EDF),

was instrumental in banning the

pesticide

DDT. An emeri-

tus professor at the Marine Sciences Research Center at the

State University of New York at Stony Brook, Wurster is an

expert on the environmental effects of toxic

chemicals

.

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Wurster’s interest

in birds was evident at a young age. He attended Quaker

schools—Germantown Friends and Haverford College—

receiving his bachelor’s of science degree in 1952. He earned

a master of science degree in chemistry from the University

of Delaware in 1954 and a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from

Stanford University in 1957. Subsequently Wurster spent a

year in Innsbruck, Austria, as a Fulbright Fellow. From 1959

to 1962, he worked as a research chemist at the Monsanto

Research Corporation.

In 1963, as a research associate in biology at Dart-

mouth College in New Hampshire, Wurster demonstrated

that the ubiquitous pesticide DDT was killing the campus

birds. DDT sprayed on elm trees killed 70% of the robins

in just two months. Myrtle warblers, who were not even on

the campus at the time of the spraying, also were killed, as

were all of the chipping sparrows. Furthermore DDT was

not saving the trees from fatal blight. Following a two-year

battle by Wurster and his colleagues, the local spraying of

DDT was halted.

After moving to Stony Brook in 1965 as an assistant

professor of biology, Wurster continued his studies on the

harmful effects of DDT. Among other results, he found

that high concentrations of DDT in Long Island osprey

were associated with thin eggshells and poor reproduction.

Much of his work was published in the prestigious journal

Science.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Charles Frederick Wurster

At Stony Brook, Wurster joined the Brookhaven

Town Natural Resources Committee, a group of scientists,

lawyers, and citizens. In one of the first-ever legal actions

to protect the

environment

, the committee forced Suffolk

County to stop spraying DDT for mosquito control in the

marshes of Long Island. In 1967 the committee incorporated

as the EDF. The EDF’s first major victory came with the

1972 nationwide ban on DDT, with Wurster in charge of

the scientific arguments. Wurster is credited with creating

a network of scientific expertise within the EDF that lent

credibility to the organization. In 1973, while on sabbatical

in New Zealand, Wurster helped found the Environmental

Defence Society (EDS), modeled on the EDF.

Wurster served as Associate Professor of Environmen-

tal Sciences at the Marine Sciences Research Center from

1970 until 1994 when he became an emeritus professor. His

research has focused on DDT,

polychlorinated biphenyls

(PCBs), and other

chlorinated hydrocarbons

, and their

effects on birds and

phytoplankton

(marine plants at the

base of the food web). He also has studied the

mortality

of diving birds caught on the longlines used for tuna fishing.

Wurster’s interest in the environmental sciences and public

policy has continued. He was instrumental in the banning

of the pesticides Dieldrin and Aldrin. In 1990 Wurster

assisted the U.S. Department of Justice in its legal case

against the Montrose Chemical Corporation, formerly the

world’s largest producer of DDT. The EDF first sued Mon-

trose in 1970 to stop it from dumping DDT into the Santa

Monica Bay. In 2000 Montrose, now owned by other com-

panies, was finally ordered to pay for the clean-up of 17 mi

2

(44 km

2

) of ocean floor. A fellow of the American Associa-

tion for the Advancement of Science, Wurster was a director

of

Defenders of Wildlife

from 1975 to 1984 and a trustee of

the

National Parks and Conservation Association

from

1970 to 1979. He continues as a director of the EDS.

From its beginnings as a small group meeting at the

Brookhaven National Laboratory, Environmental Defense

1540

has grown into one of world’s largest and most influential

environmental organizations, with 400,000 members and a

staff of 250 that includes scientists, economists, and lawyers.

Wurster continues to work with the EDF program for the

establishment of marine preserves in the United States and

in the open ocean and he leads ecological tours for the EDF.

[Margaret Alic Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Mosser, J. L., N. S. Fisher, and C. F. Wurster. “Polychlorinated Biphenyls

and DDT Alter Species Composition in Mixed Cultures of Algae.” Science

176 (1972): 533–5.

Wurster, C. F. “Beetles and Dieldrin.” Science 163 (1969): 229.

Wurster, C. F. “DDT and Robins.” Science 159 (1968): 1413–4.

Wurster, C. F. “DDT Reduces Photosynthesis by Marine Phytoplankton.”

Science 159 (1968): 1474–5.

O

THER

Bowman, Malcolm J. “Charles Wurster: Environmental Hero and Advocacy

Pioneer.” EDS News, January 2002 [cited June 10, 2002]. <www.eds.org.nz/

News_Vol_4.htm>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Dr. Charles F. Wurster, Marine Sciences Research Center, State University

of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY USA 11794-5000 (631)

632-8738, Email: Charles.F.Wurster@stonybrook.edu,

Environmental Defence Society, PO Box 95 152 Swanson, Aukland, New

Zealand 1008 (64-9) 810-9594, Fax: (64-9) 810-9120, Email:

manager@eds.org.nz, <http://www.eds.org.nz>

Environmental Defense, 257 Park Avenue South, New York, NY USA

10010 (212) 505-2100, Fax: (212) 505-2375, Toll Free: (800) 684-3322,

Email: members@environmentaldefense.org, <http://www.environmental

defense.org>

WWF

see

World Wildlife Fund

X

X ray

Discovered in 1895 by German physicist Wilhelm K. Roent-

gen, x rays are a form of electromagnetic radiation, widely

used in medicine, industry, metal detectors, and scientific

research. X rays are most commonly used by doctors and

dentists to make pictures of bones, teeth, and internal organs

in order to find breaks in bones, evidence of disease, and

cavities in teeth.

Since x rays are a form of

ionizing radiation

, they

can be very dangerous. They penetrate into, and are absorbed

by, plants and animals and can age, damage, and destroy

living tissue. They can also cause skin burns, genetic muta-

tions,

cancer

, and death at high levels of exposure. The

effects of ionizing radiation tend to be cumulative, and every

dose adds to the possibility of further damage.

Some authorities feel that people should try to mini-

mize their exposure to such radiation and avoid being x-

rayed unless absolutely necessary. This is especially true of

pregnant women, since studies show a much higher rate of

childhood

leukemia

and other diseases among children who

were exposed to x rays in utero. Ironically, fear of malpractice

suits has prompted many doctors to increase the number of

x rays performed while examining patients for disease. See

also Radiation exposure

Xenobiotic

Designating a foreign and usually harmful substance or orga-

nism in a biological system. Xenobiotic, derived from the

Greek root xeno, meaning “stranger” or “foreign,” and bio,

meaning “life,” describes some toxic substances,

parasites

,

and symbionts. Food, drugs, and poisons are examples of

xenobiotic substances in individual organisms, and their tox-

icity is linked to the level of consumption. In communities

or

species

, xenobiosis happens when two distinct species,

such as different kinds of ants, share living space like nests.

At the

ecosystem

level, toxic waste, when bioaccumulated

1541

in the

food chain/web

, is xenobiotic. See also Bioaccumula-

tion; Hazardous waste; Symbiosis

Xeriscaping

see

Arid landscaping

Xylene

The term “xylene” refers to any of three

benzene

derivative

isomers that share the same chemical formula, C

6

H

4

(CH

3

)

2

,

but differ in their molecular structure. They are useful as

solvents, as additives to improve the

octane rating

of avia-

tion fuels, and as raw materials in the manufacture of fibers,

films, dyes, and other synthetic products. Because of their

high volatility they are classified as aromatic

hydrocarbons

(volatile compounds containing only

carbon

and

hydrogen

atoms). Xylene fractions were first isolated from

coal

tar in

the mid-nineteenth century in Germany. Coal tar is the

thick liquid product of the carbonization, or destructive dis-

tillation, of coal, a process in which coal is heated without

air to temperatures above 1,600°F (862°C). Benzene and

toluene

, two aromatic hydrocarbons similar to xylene, are

formed in the same process. Coal tar remained the source

for xylene until industrial demand outgrew the supply. Later,

techniques were developed to obtain xylene from

petroleum

refining, and today petroleum is a major source.

The three isomeric xylenes are classified by the ar-

rangement of the methyl (CH

3

) groups substituting for hy-

drogen atoms on the benzene ring. In each case, the methyl

groups replace two of the hydrogens attached to the six-

carbon benzene ring, but the structure and chemical proper-

ties of each isomer depend on which hydrogens are replaced.

Ortho-xylene (o-xylene) has methyl groups on two adjacent

carbons in the benzene ring structure, while in meta-xylene

(m-xylene) the methyl-containing carbons are separated by

a hydrogen-containing carbon. In para-xylene (p-xylene),

two hydrogen-bearing carbons separate the methyl-con-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Xylene

taining carbons, placing the methyl groups at opposite ends

of the molecule. Ortho-xylene, the least volatile of the three

forms, serves as raw material for the manufacture of coatings

and

plastics

. Para-xylene is used to manufacture polyesters.

Meta-xylene, less useful than the other forms, is used to make

coatings, plastics, and dyes. A commercial xylene mixture in

the form of a colorless, flammable, non-viscous, toxic liquid

is used as a solvent for lacquers and

rubber

cements. Emulsi-

fied xylene has been used as an economical and effective

way of controlling aquatic weeds in

irrigation

systems, but

concentrations must be carefully controlled to avoid harming

plants and fish exposed to the residues.

Xylene’s volatility leads to its easy escape into the

atmosphere

. Unless care is taken, its fumes soon permeate

the air in laboratories where it is used. Although its solubility

in water is quite limited, xylene (along with benzene and

toluene) is classified as one of the primary components of

the “water-soluble” fraction of petroleum. The widespread

use of xylene in manufacturing has resulted in significant

releases of the chemical into the air and water of the

environ-

ment

. Xylene’s toxicity in water is influenced by

salinity

,

1542

temperature, and the presence of other toxic materials. It

affects cell permeability and acts as a

neurotoxin

for fish

and other animals. At high concentrations of xylene, fish

exhibit a series of behavioral changes including restlessness

(rapid and erratic swimming), loss of equilibrium, paralysis,

and death. Although each of the three forms of xylene can

be detoxified by

microorganisms

, para-xylene is more diffi-

cult to detoxify, and therefore a more persistent threat.

[Douglas C. Pratt]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Buikema, L., and A. C. Hendricks. Benzene, Xylene, and Toluene in Aquatic

Systems: A Review. Washington, DC: American Petroleum Institute, 1980.

Hancock, E. G., ed. Toluene, the Xylenes, and Their Industrial Derivatives.

Amsterdam; New York: Elsevier, 1982.

Parmeggiani, L., ed. Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety. 3rd

ed. Geneva: International Labour Office, 1983.

Walsh, D. F., ed. Residues of Emulsified Xylene in Aquatic Weed Control

and Their Impact on Rainbow Trout, Salmo gairdneri. Denver, CO: U.S.

Dept. of the Interior [Bureau of Reclamation, Engineering and Research

Center, Division of General Research, Applied Sciences Branch], 1977.

Y

Yard waste

As the field of solid

waste management

becomes more

developed and specialized, the categories into which

solid

waste

is sorted and managed become more numerous. Yard

waste—often called vegetative waste—includes leaves, grass

clippings, tree trimmings, and other plant materials that are

typically generated in outdoor residential settings. De-

pending on the season and the neighborhood, leaves may

account for 5–30% of the total

municipal solid waste

stream, grass clippings may comprise 10–20%, and wood

may form about 5–10%. Yard waste does not include food

and animal wastes except possibly as impurities. Yard waste

is usually perceived as cleanest type of solid waste, in contrast

to household refuse or industrial and commercial trash.

Since yard waste is almost entirely vegetative in nature,

it lends itself easily to

composting

. Composting is the natu-

ral breakdown of organic matter by

microbes

, in the pres-

ence of oxygen, to form a stable end product called compost.

In the management of yard waste, this natural process de-

creases the need for

landfill

space and produces

soil

amend-

ment as an end product.

Beneficial use and composting of yard waste may be

practiced in the homeowner’s backyard or in the waste man-

agement areas set up by townships and municipalities. Not

all forms of yard waste lend themselves equally well to com-

posting. In fact, woody materials such as tree trunks may

be better managed and used by shredding into wood chips

or saw dust, since wood is very resistant to composting.

Leaves are most suitable for composting and provide the

richest and most stable base of material and nutrients. With

sufficient oxygen, water, and turnover, leaves can usually be

broken down in a matter of weeks. Grass clippings decom-

pose so quickly that they need to be mixed with slower-

degrading materials (such as leaves) in order to slow down

and regulate the rate of

decomposition

. Control over the

decomposition process is essential because of the potential

for problems such as noxious odors. If the decomposition

process is too rapid and proceeds without sufficient oxygen,

1543

the process becomes

anaerobic

and generates odors that

can be highly unpleasant. In seasons other than fall, when

the volume of leaves in yard waste is relatively small, many

experts recommend that grass clippings be used as

mulch

rather than as compost to avoid the potential for odor.

In urban and mixed

land use

neighborhoods, yard

waste may inadvertently contain

plastics

, papers, and other

non-degradable materials. In some areas, the bagging of yard

waste may involve the use of plastic bags. Depending on the

efficiency of separation at the waste management area, these

inert materials may find their way into the final compost

product and lower the esthetics and usefulness of the

compost.

[Usha Vedagiri]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Strom, P. F., and M. S. Finstein. Leaf Composting and Yard Waste Manage-

ment for New Jersey Municipalities. New Jersey Department of Environmen-

tal Protection and Energy, 1993.

Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park has the distinction of being the

world’s first

national park

. With an area of 3,472 sq mi

(8,992 sq km), Yellowstone is the largest national park in

the lower 48 states. This is an area larger than Rhode Island

and Delaware combined. Although primarily in Wyoming

(91%), 7.6% of the park is in Montana and the remaining

1.4% is in Idaho.

John Colter, a member of the Lewis and Clark expedi-

tion of 1803–1806, was probably the first white man to visit

and report on the Yellowstone area. At that time the only

Native Americans living year-round in the area were a mixed

group of Bannock and Shoshone known as “sheepeaters.” In

1859, the legendary trapper and explorer Jim Bridger, who

had been reporting since the 1830s about the wonders of the

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Yellowstone National Park

A grizzly bear with its cubs in Yellowstone National Park. (National Park Service Harpers Ferry Center. Reproduced by

permission.)

region, led the first government expedition into the area. The

discovery of gold in the Montana Territory in the 1860s

brought more expeditions. In 1870, the Washburn-Lang-

ford-Doane expedition came to verify the reports about the

wonders of the area. They spent four weeks naming the fea-

tures, including Old Faithful, the most famous geyser in the

world. Legend states that while the 19 members of this expe-

dition sat around a campfire, reflecting on the beauty of the

area, they came up with the idea of turning the region into a

national park. The truth of the legend is debatable, yet there

is no doubt that it was the lecturing and writing of these men

that promptedthe United States

GeologicalSurvey

tosend a

follow-up groupto the park in 1871. Reportsand photographs

from the U.S. Geological Survey expedition stimulated the

drafting of legislation to create the first national park. Because

of the prevalent utilitarian philosophy and the country’s poor

economic condition, the battle for the park was difficult and

hard-fought. Eventually the park proponents were successful,

and on March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the

bill establishing the park.

1544

Because Congress did not allocate any money for park

maintenance or protection, the early years of the park were

marked by vandalism,

poaching

, the deliberate setting of

forest fires, and other destructive behaviors. Eventually, in

1886, the U.S. Army took responsibility for the park. They

remained in the role of park managers until the

National

Park Service

was formed in 1916.

Water covers about 10% of the park. The largest body

of water is Yellowstone Lake, with a surface area of 136 sq mi

(352 sq km). It is one of the largest, highest, and coldest lakes

in North America. The park has one of the highest waterfalls

in the United States (Lower Yellowstone Falls, 308 ft; 93.87

m) and the top three trout fishing streams in the world. Ap-

proximately 10,000 thermal features can be found in the park.

In fact, there are more geysers (200–250) and hot springs in

the park than in the rest of the world put together.

The park has a great abundance and diversity of

wild-

life

. It has the largest concentration of mammals in the

lower 48 states. There are 58

species

of mammals in the

park, including two species of bears and seven species of

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Yokkaichi asthma

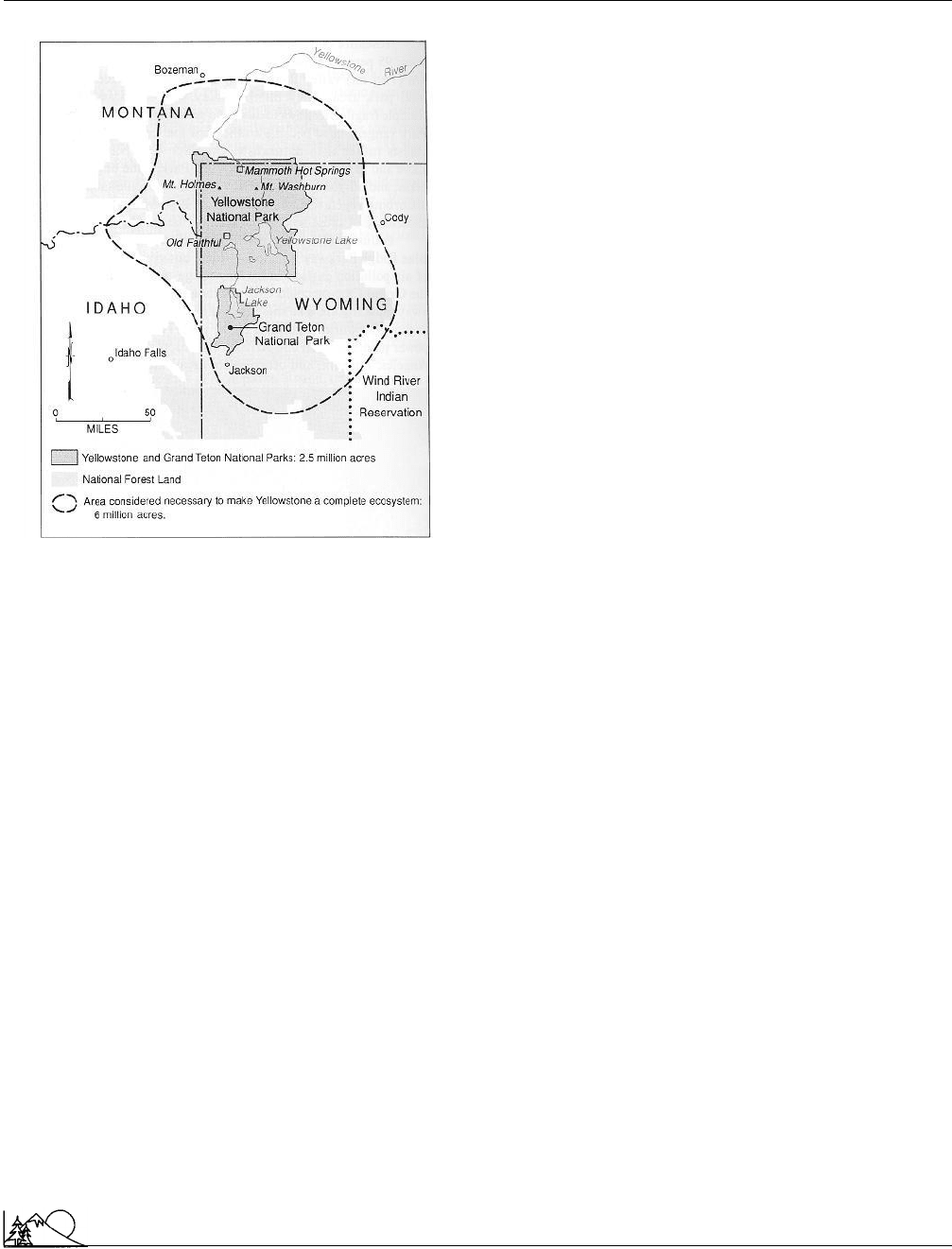

Map of the Yellowstone ecosystem complex or

biogeographical region, which extends far be-

yond the boundaries of the park. (McGraw-Hill

Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

ungulates. It is one of the last strongholds of the

grizzly

bear

and is the only place where a

bison

herd has survived

continuously since primitive times. Yellowstone is noted

also for having the largest concentration of elk to be found

anywhere in the world. Besides mammals, the park is home

for 279 species of birds, 18 species of fish, five species of

reptiles, and four species of amphibians.

However, one of the continuing difficulties at Yel-

lowstone and other national parks is that Yellowstone is not

a self-contained

ecosystem

. Its boundaries were established

through a variety of political compromises, and lands around

the park that once provided a buffer against outside events

are being developed. Airsheds, watersheds, and animal

mi-

gration

routes extend far beyond park boundaries, yet they

dramatically affect conditions within the park. Yellowstone

is but one example of the need to manage entire biogeo-

graphical areas to preserve natural conditions within a na-

tional park.

[Ted T. Cable]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Frome, M. National Park Guide. 19th ed. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1985.

1545

O

THER

Yellowstone Fact Sheet. National Park Service, U.S. Department of Inte-

rior, 1992.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Yellowstone National Park, P.O. Box 168, Yellowstone National Park,

WY 82190-0168 (307) 344-7381, Email: yell_visitor_services@nps.gov,

<http://www.nps.gov/yell>

Yokkaichi asthma

Nowhere is the connection between industrial development

and environmental and human health deterioration more

graphically demonstrated than at Yokkaichi, Japan. An inter-

national port located on the Ise Bay, Yokkaichi was a major

textile center by 1897. The shipping business shifted to

nearby Nagoya in 1907, and Yokkaichi filled in its coastal

lowlands in a successful bid to attract modern industries,

especially chemical processing, steel production, and oil and

gasoline

refining.

Spurred by both the World War II demand and the

postwar recovery effort, several more

petrochemical

compa-

nies were added through the 1950s, creating an oil refinery

complex called the Yokkaichi Kombinato. In 1959 it began

24-hour operations, and the sparkle of hundreds of electric

lights became known as the “million-dollar night view.”

Although citizens took pride in the growing industrial com-

plex, their enthusiasm waned when

air pollution

and

noise

pollution

created human health problems. As early as 1953,

the central government sent a research group to try to dis-

cover the cause, but no action was taken. Instead, the petro-

chemical complex was expanded.

As citizens began to complain about breathing diffi-

culties, scientists documented a high correlation between

airborne

sulfur dioxide

concentrations and bronchial

asthma

in schoolchildren and chronic

bronchitis

in individ-

uals over 40. Despite this knowledge, a second industrial

complex was opened in 1963. In the Isozu district of Yokkai-

chi, the average concentration of sulfur dioxide was eight

times that of unaffected districts. Taller smokestacks spread

pollution

over a wider area but did not resolve the problem;

increased production also added to the volume discharged.

Despite

resistance

, a third industrial complex was added

in 1973, one of the largest

petroleum

refining and ethylene

producing facilities in Japan.

As the petrochemical industries continued to expand,

local citizens’ quality of life deteriorated. In the early years,

heavy

smoke

was emitted by

coal combustion

, and parents

worried about the exposure of schoolchildren whose play-

ground was close to the emissions source. Switching from

coal to oil in the 1960s seemed to be an improvement, but

the now-invisible stack gases still contained large quantities

of sulfur oxides, and more people developed

respiratory

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Yosemite National Park

diseases

. By 1960, fish from the local waterways had devel-

oped such a bad taste that they were unsalable, and fishermen

demanded compensation for their lost livelihood. By 1961,

48% of children under six, 30% of people over 60, and 19%

of those in their twenties had respiratory abnormalities. In

1964, a pollution-free room was established in the local

hospital where victims could take refuge and breathe freely.

Even so, two desperate people committed suicide in

1966, and 12 Yokkaichi residents who had been trying to

resolve the problem by negotiation finally filed a damage

suit against the Shiohama Kombinato in 1967. In 1972, the

judge awarded the plaintiffs $286,000 in damages to be paid

jointly by the six companies. This was the first case in which

a group of Japanese companies were forced to pay damages,

making other kombinatos vulnerable to similar suits. As a

consequence of the successful litigation by the Yokkaichi

victims, the Japanese government enacted a basic antipollu-

tion law in 1967. Two years later, the Law Concerning

Special Measures for the Relief of Pollution-Related Patients

was enacted. It applied to chronic bronchitis/bronchial

asthma victims not only from Yokkaichi but also Kawasaki

and Osaka. In addition, national air-pollution standards were

strengthened to require that oil refineries adhere to air pollu-

tion abatement policies.

By 1975, the annual mean sulfur dioxide levels had

decreased by a factor of three, below the target level of 0.017

parts per million

(ppm). The harmful effects on residents

of Yokkaichi also decreased. In 1973, the Law Concerning

Compensation for Pollution-Related Health Damages and

Other Measures aided sufferers of chronic bronchitis and

bronchial asthma from the other affected areas of Japan,

especially Tokyo. By December 1991, 97,276 victims

throughout Japan, including 809 from Yokkaichi, were eligi-

ble for compensation. See also Air-pollutant transport; Envi-

ronmental law; Industrial waste treatment; Tall stacks

[Frank M. D’Itri]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Huddle, N., and M. Reich. Island of Dreams: Environmental Crisis in Japan.

Tokyo, Japan: Autumn Press, 1975.

P

ERIODICALS

Kitabatake, M., H. Manjurul, P. Feng Yuan, et al. “Trends of Air Pollution

Versus Those of Consultation Rate and Mortality Rate for Bronchial

Asthma in Individuals Aged 40 Years and Above in the Yokkaichi Region.”

Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi 50, no. 3 (1995): 737.

O

THER

“Diseases By Air Pollution.” In Quality of the Environment in Japan. Tokyo,

Japan: Environmental Agency, Government of Japan, 1990.

1546

Yosemite National Park

Yosemite National Park is a 748,542-acre (303,160-ha) park,

located on the western slope of the Sierra Nevadas in north-

ern California. The name Yosemite comes from the name

of an Indian tribe, the U-zu-ma-ti, who were massacred in

1851 by soldiers sent by the governor of California for refus-

ing to attend a reservation agreement meeting.

By the mid-1800s, Yosemite had become a thriving

tourist attraction. As word of Yosemite’s wonders spread

back to the East Coast, public pressure led Congress to

declare that the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove

of giant sequoias be held “inalienable for all time.” President

Abraham Lincoln signed this law on June 30, 1864, turning

this land over to the state of California and thereby giving

Yosemite the distinction of being the first state park. Con-

cern about sheep

overgrazing

in the high meadows led to

the designation of the high country as a

national park

in 1890.

The person most strongly associated with the protec-

tion of Yosemite and its designation as a national park is

naturalist and philosopher

John Muir

. Muir, sometimes

called the “Thoreau of the West,” first came to Yosemite

in 1868. He devoted the next 40 years of his life to ensuring

that the

ecological integrity

of the region was maintained.

In 1892, Muir founded the

Sierra Club

to organize efforts

to gain national park status for the Yosemite Valley.

Yosemite National Park is famous for its awesome and

inspiring scenery. Geologic wonders include the mile-wide

Yosemite valley surrounded by granite walls and peaks such

as El Capitan (7,569 ft [2,307 m] above sea level; 3,593 ft

[1,095 m] from base) and Half Dome (8,842 ft [2,695 m]

above sea level; 4,733 ft [1,443 m] from base). Spectacular

waterfalls include Yosemite Falls (Upper 1,430 ft [436 m],

Middle 675 ft [206 m], Lower 320 ft [98 m]), Ribbon Falls

(1,612 ft [491 m]), Bridalveil Falls (620 ft [189 m]), Sentinel

Falls (2,001 ft [610 m]), Horsetail Falls (1,001 feet [305

meters]), and Vernal Falls (317 ft [97 m]).

The park supports an abundance of plant and animal

life. Eleven

species

of fish, 29 species of reptiles and am-

phibians, 242 species of birds, and 77 species of mammals

can be found in the park. There are approximately 1,400

species of flowering plants, including 37 tree species. The

most famous of the tree species found here is the giant

sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum). The park has three

groves of giant sequoias, the largest being the Mariposa

Grove with 500 mature trees, 200 of which exceed 10 ft (3

m) in diameter.

Because of the high degree of development and the

congestion from the large numbers of visitors (over four

million per year as of 2002), some have disparagingly referred

to the Valley as “Yosemite City.” Yosemite has become a