Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Wise use movement

Sellafield, a remote farm area of northern England, to supply

nuclear power

to the region. This early reactor was de-

signed with a large graphite block in which cans containing

the

uranium

fuel were embedded. The graphite served to

slow down fast-moving neutrons produced during

nuclear

fission

, allowing the reactor to operate more efficiently.

Graphite behaves in a somewhat unusual way when

bombarded with neutrons. Water, its modern counterpart,

becomes warmer inside the reactor and circulates to transfer

heat away from the core. Graphite, on the other hand, in-

creases in volume and begins to store energy. At some point

above 572°F (300°C), it may then suddenly release that

stored energy in the form of heat.

A safety system that allowed this stored energy to be

released slowly was installed in the Windscale reactor. On Oc-

tober 7, 1957, however, a routine procedure designed to re-

lease energy stored in the graphite cube failed, and a huge

amount of heat was released in a short period of time. The

graphite moderator caught fire, uranium metal melted, and

radioactive gases were released to the

atmosphere

. The fire

burned for two days before it was finally extinguished with

water.

Fortunately, the area around Windscale is sparsely

populated, and no immediate deaths resulted from the acci-

dent. However, quantities of radiation exceeding safe levels

were observed shortly after the accident in Norway, Den-

mark, and other countries east of the British islands. British

authorities estimate that 30 or more

cancer

deaths since

1957 can be attributed to

radioactivity

released during the

accident. In addition, milk from cows contaminated with

radioactive iodine-131 had to be destroyed. The British

government eventually decided to close down and seal off

the damaged nuclear reactor.

Four decades after the accident, Sellafield is still in

the news. In 1991, the

Radioactive Waste Management

Advisory Committee recommended that Sellafield be chosen

as the site for burying Britain’s high-, low-, and intermedi-

ate-level radioactive wastes. A complex network of tunnels

2,500 ft (800 m) below ground level would be ready to accept

wastes by the year 2005, according to the committee’s plan.

Although some environmental groups object to the

plan, many citizens do not seem to be concerned. In spite

of the high levels of radiation buried in the old plant, Sella-

field has become one of the most popular vacation spots for

Britons. See also High-level radioactive waste; Liquid metal

fast breeder reactor; Low-level radioactive waste; Radiation

exposure; Radiation sickness

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Dresser, P. D., ed. Nuclear Power Plants Worldwide. Detroit, MI: Gale

Research, 1993.

1527

P

ERIODICALS

Dickson, D. “Doctored Report Revives Debate on 1957 Mishap.” Science

(February 5, 1988): 556–557.

Goldsmith, G., et al. “Chernobyl: The End of Nuclear Power?” The Econo-

mist 16 (1986): 138–209.

Herbert, R. “The Day the Reactor Caught Fire.” New Scientist (October

14, 1982): 84–87.

Howe, H. “Accident at Windscale: World’s First Atomic Alarm.” Popular

Science (October 1958): 92–95+.

Pearce, F. “Penney’s Windscale Thoughts.” New Scientist (January 5, 1988):

34–35.

Urquhart, J. “Polonium: Windscale’s Most Lethal Legacy.” New Scientist

(March 31, 1983): 873–875.

Winter range

Winter range is an area that animals use in winter for food

and cover. Generally, winter range contains a food source

and thermal cover that together maintain the organism’s

energy balance through the winter, as well as some type of

protective cover from predators. Although some

species

of

animals have special adaptations, such as hibernation, to

survive winter climates, many must migrate from their sum-

mer ranges when conditions there become too harsh. Elk

(Cervus elaphus) inhabiting mountainous regions, for exam-

ple, often move from higher ground to lower in the fall,

avoiding the early snow cover at higher elevations. Nothern

populations of caribou or reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) often

travel over 600 mi (965 km) between their summer ranges

on the

tundra

and their winter ranges in northern wood-

lands. Still more extreme, the summer and winter ranges of

some animals are located on different continents. North

American birds known as

neotropical migrants

(including

many species of songbirds) simply fly to Central or South

America in the fall, inhabiting winter ranges many thousands

of miles from their summer breeding grounds.

WIPP

see

Waste Isolation Pilot Plan

Wise use movement

The wise use movement was developed in the late 1980s as

a response to the environmental movement and increasing

government regulation. A grassroots environmental move-

ment came about because of perceived impotence of federal

regulatory agencies to either regulate the continuing flow of

untested toxics into the

environment

or clean up the massive

mountain of accumulating waste through the Superfund law.

The wise use movement has begun to address these same

issues, but basically from a financial standpoint.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Wise use movement

Recognizing that cleanup is far more costly than antici-

pated and persisting in the belief that

public land

should

be available for business use, the wise use movement has

begun to garner a growing constituency. One of the major

new themes, for example, is that low exposures to

chemicals

and radiation are not harmful to humans or ecosystems, or

at least not harmful enough to warrant the billions of dollars

needed to protect and clean up the environment. Some com-

panies, rather than changing manufacturing processes or

doing research on less toxic chemicals, have chosen to con-

tinue doing business as usual and are among the leaders of

the wise use movement.

The oil, mining, ranching, fishing, farming, and

off-

road vehicles

industries—which are most affected by wet-

land regulation and restrictions on land use—also form a

constituency for the wise use movement. The fight for con-

trol over land is an old one. Traditionally, timber and mining

companies have sought unrestricted access to public lands.

Environmental groups such as the

Wilderness Society

, the

National Audubon Society

, the

Sierra Club

, and

the Na-

ture Conservancy

have fought to restrict access. This con-

troversy has been in open debate since at least 1877. At that

time, Carl Schurz, then Secretary of the Interior, proposed

the idea of national forests, which would be rationally man-

aged instead of exploited. Today, the debate between the

environmental and wise use movements represents little

more than the longstanding controversy over the best use

of public lands—the 29.2% of the total area of the United

States owned by the federal government. At present, the

wise use movement is most active in the western states with

regard to the debate over

land use

, but it is moving into

the East as well, where the movement is championed by

developers who want to abolish

wetlands

regulations.

At this point, several thousand small groups and count-

less individuals identify to some degree with the wise use

movement. They claim they are the only true environmental-

ists and label traditional environmentalists “preservationists

who hate humans.” The wise use aim is to gut all environ-

mental legislation on the theory that regulation has ruined

America by curtailing the rights of property owners. Many

wise use advocates avoid complexity by simply denying the

existence of many widely-accepted theories. For example,

some wise use leaders insist that the

ozone layer depletion

problem was manufactured by the National Aeronautics and

Space Administration (NASA) and isn’t a real threat.

The philosophy of the wise use movement is based

on a book by Ron Arnold and Alan Gottlieb, The Wise Use

Agenda (1988). The movement took a major step forward

after a conference held in Reno, Nevada in August of 1988,

sponsored by the Center for the Defense of Free Enterprise.

Funding for the conference came from large corporations

along with a number of right-wing business, political, and

1528

religious organizations. The conference was attended by

roughly 300 people from across the United States and Can-

ada, representing those industries that feel most threatened

by current regulation. These people became the activist

founders of the wise use movement. Calling themselves the

“new environmentalists,” they moved on to organize grass-

roots support.

The wise use movement has developed a 25-point

agenda, seeking to foster business use of

natural re-

sources

. Wise use goals are considered environmentally

damaging and are opposed by the traditional environmen-

talist movement. The wise use movement pursues the

development of

petroleum

resources in the

Arctic Na-

tional Wildlife Refuge

in Alaska. It advocates

clear-

cutting

of

old-growth forest

and replanting of public

lands with baby trees, the latter at government expense.

It aims to open public lands, including

wilderness

and

national parks, to mining and

oil drilling

. It seeks to

rescind all federal regulation of those

water resources

originating in or passing through the states, favoring state

regulation exclusively. The wise use movement further

advocates the use of national parks for recreational purposes

and a stop to all regulation that may exclude park visitors

for protective purposes. It opposes any further restrictions

on

rangelands

as livestock grazing areas. It advocates

the prevention and immediate

extinction

of all wildfires

to protect timber for commercial harvesting.

The above is but a sampling of the agenda of wise use

groups in the United States and abroad. The movement is

using established corporate structures as a base, which pro-

vide training and support to activists. Corporations are now

being joined by timber and

logging

associations, chambers

of commerce, farm bureaus, and local organizations. The

wise use movement is growing because of grassroots support.

Small farmers and ranchers and small mining and logging

operations have come under tremendous financial pressure.

Resources are dwindling, and costs are going up. With in-

creased mechanization, small business owners and their live-

lihoods are threatened. To give one example, government

scientists, after conducting five separate studies, recom-

mended that timber harvests in the Pacific Northwest’s an-

cient forests be reduced by 60% from what they were in the

mid-1980s. Loggers would not be able to cut more than

two billion board feet of wood a year from national forests

in Oregon and Washington. That is substantially below the

five billion-plus board feet the industry harvested on those

lands annually from 1983 to 1987, before the dispute over

protection of the

northern spotted owl

(Strix occidentalis

caurina) and old-growth forests wound up in court. The

wise use movement is one effort to rally behind the people

who risk the loss of work, and who may see

environmen-

talism

as their enemy.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Abel Wolman

In a strange irony, the grassroots activists of both

the environmental movement and the wise use movement

have much in common. The rank and file in the wise

use movement represent the same kinds of concerns for

environmental justice. Both sides see their well-being

threatened, whether in terms of property values, livelihoods,

or health, and have organized in self-defense. See also

Environmental ethics

[Liane Clorfene Casten and Marijke Rijsberman]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Gottlieb, A. M., and R. Arnold. The Wise Use Agenda. Bellevue, WA: Free

Enterprise Press, 1989.

O

THER

Mendocino Environmental Center Newsletter 12 (Summer/Fall 1992).

Rachel’s Hazardous Waste News (Environmental Research Foundation). Nos.

332, 335.

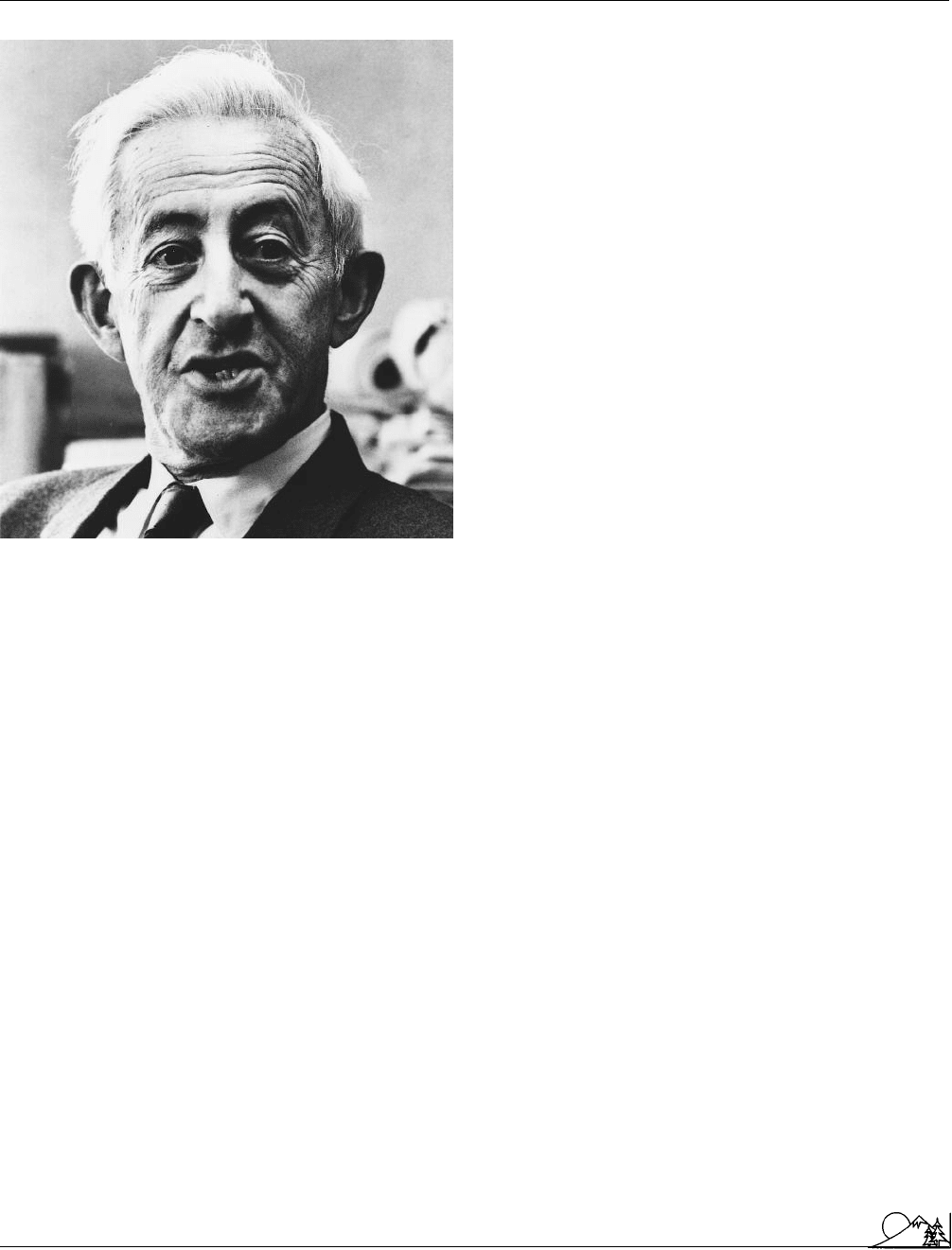

Abel Wolman (1892 – 1989)

American engineer and educator

Born June 10, 1892 in Baltimore, the fourth of six children of

Polish-Jewish immigrants, Wolman became one of the

world’s most highly respected leaders in the field of sanitary

engineering, which evolved into what is now known as

envi-

ronmental engineering

. His contributions in the areas of

water supply, water and

wastewater

treatment, public

health, nuclear reactor safety, and engineering education

helped to significantly improve the health and prosperity of

people not only in the United States but also around the world.

Wolman attended Johns Hopkins University, earning

a bachelor’s degree in 1913 and another bachelor’s in engi-

neering in 1915. He was one of four students in the first

graduating class in the School of Engineering. In 1937,

having already made major contributions in the field of

sanitary engineering, he was awarded an honorary doctorate

by the school. That same year he helped establish the Depart-

ment of Sanitary Engineering in the School of Engineering

and the School of Public Health, and served as its Chairman

until his retirement in 1962. As a professor emeritus from

1962 to 1989, he remained active as an educator in many

different arenas.

From 1914 to 1939, Wolman worked for the Maryland

State Department of Health, serving as Chief Engineer from

1922 to 1939. It was during his early years there that he made

what is regarded as his single most important contribution.

Working in cooperation with a chemist, Linn Enslow, he

standardized the methods used to chlorinate a municipal

drinking-water supply

.

1529

Although

chlorine

was already being applied to drink-

ing water in some locations, the scientific basis for the prac-

tice was not well understood and many utilities were reluctant

to add a poisonous substance to the water. Wolman’s techni-

cal contributions and his persuasive arguments regarding the

potential benefits of

chlorination

encouraged many munici-

palities to begin chlorinating their water supplies. Subse-

quently, the death rates associated with water-borne

com-

municable diseases

plummeted and the average life span

of Americans increased dramatically. He assisted many other

countries in making similar progress.

During the course of his long and illustrious career,

spanning eight decades, Wolman held over 230 official posi-

tions in the fields of engineering, public health, public works,

and education. He served as a consultant to numerous utili-

ties, state and local governments and agencies, and federal

agencies, including the U.S.

Public Health Service

, the

National Resources Planning Board, the

Tennessee Valley

Authority

, the

Atomic Energy Commission

, the U.S.

Geo-

logical Survey

, the

National Research Council

, the Na-

tional Science Foundation, the Department of Defense, the

Army, the Navy, and the Air Force.

On the international scene, Wolman served as an advi-

sor to more than 50 foreign governments. For many years

he served as an advisor to the World Health Organization

(WHO), and he was instrumental in convincing the agency

to broaden its focus to include water supply,

sanitation

,

and sewage disposal. He also served as an advisor to the Pan

American Health Organization.

Wolman was an active member of a broad array of

professional societies, including the

National Academy of

Sciences

, the National Academy of Engineering, the Ameri-

can Public Health Association, the American Public Works

Association, the American Water Works Association, the

Water Pollution

Control Federation, and the American

Society of Civil Engineers. His leadership in these organiza-

tions is exemplified by his service as President of the Ameri-

can Public Health Association in 1939 and the American

Water Works Association in 1942.

Known as an avid reader and a prolific writer, Wolman

authored four books and more than 300 professional articles.

For 16 years (from 1921 to 1937) he served as editor-in-

chief of the Journal of the American Water Works Association.

He also served as Associate Editor of the American Journal of

Public Health (1923–1927) and editor-in-chief of Municipal

Sanitation (1929–1935).

Wolman was the recipient of more than 60 profes-

sional honors and awards, including the Albert Lasker Spe-

cial Award (American Public Health Association, 1960), the

National Medal of Science (presented by President Carter,

1975), the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement

(1976), the Environmental Regeneration Award (Rene

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Wolves

Abel Wolman. (The Ferdinand Hamburger Jr. Archives

of Johns Hopkins University. Reproduced by permission.)

Dubos Center for Human Environments, 1985), and the

Health for All by 2000 Award (WHO, 1988). He was an

Honorary Member of 17 different national and international

organizations, some of which named prestigious awards in

his honor.

He was greatly admired for his outstanding integrity

and widely known for the help and encouragement he gave

to others, for his keen mind and sharp wit (even at the age

of 96), for his willingness to change his mind when con-

fronted with new information, and for his devotion to his

family. His wife of 65 years, Anne Gordon, passed away in

1984. Wolman’s son, Gordon, is Chairman of the Depart-

ment of Geography and Environmental Science at Johns

Hopkins University.

[Stephen J. Randtke]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Wolman, Abel. Water, Health and Society: Selected Papers, edited by G. F.

White. Ann Arbor, MI: Books on Demand.

P

ERIODICALS

National Academy of Engineering of the United States of America. Memo-

rial Tributes 5. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1992.

ReVelle, C. “Abel Wolman, 1892–1989.” EOS 70 (29 August 1989).

APWA Reporter 56 (October 1989): 24–5.

1530

Wolves

Persecuted by humans for centuries, these members of the

dog family Canidae are among nature’s most maligned and

least understood creatures. Yet they are intelligent, highly

evolved, sociable animals that play a valuable role in main-

taining the

balance of nature

.

Fairy tales such as “Little Red Riding Hood” and “The

Three Little Pigs” notwithstanding, healthy, unprovoked

wolves do not attack humans. Rather, they avoid them when-

ever possible. Wolves do prey on rabbits, rodents, and espe-

cially on hoofed animals like deer, elk, moose, and caribou.

By seeking out the slowest and weakest animals, those that

are easiest to catch and kill, wolves tend to cull out the sick

and the lame, very old and young, and the unwary, less

intelligent, biologically inferior members of the herd. In this

way, wolves help ensure the “survival of the fittest” and

prevent overpopulation, starvation, and the spread of diseases

in the prey

species

.

Wolves have a disciplined, well-organized social struc-

ture. They live in packs, share duties, and cooperate in

hunt-

ing

large prey and rearing pups. Members of the pack,

often an extended family composed of several generations

of wolves, appear to show great interest in and affection for

the pups and for each other, and have been known to bring

food to a sick or injured companion. It is thought that the

orderly and complex social structure of wolf society, espe-

cially the submission of members of the pack to the leaders,

made it possible for early humans to socialize and domesti-

cate a small variety of wolf that evolved into today’s dogs.

The famous howls in which wolves seem to delight appear

to be more than a way of establishing territory or locating

each other. Howling seems to be part of their social culture,

often done seemingly for the sheer pleasure of it.

Nevertheless, few animals have withstood such univer-

sal, intense, and long–term persecution as have wolves, and

with little justification. Bounties on wolves have existed for

well over 2,000 years and were recorded by the early Greeks

and Romans. One of the first actions taken by the colonists

settling in New England was to institute a similar system,

which was later adopted throughout the United States. Sport

and commercial

hunting and trapping

, along with federal

poisoning

and

trapping

programs—referred to as “predator

control"—succeeded in eliminating the wolf from all of its

original range in the contiguous 48 states excepting Minne-

sota, until its later reintroduction.

The

U.S. Department of the Interior

, at the urging

of conservationists, has undertaken efforts to reestablish wolf

populations in suitable areas, like

Yellowstone National

Park

. In 1995, the 14 wolves were released to roam the park.

The group adapted extremely well and multiplied quickly. In

1997, nearby ranchers, concern that the wolves could become

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Wolves

a threat to their livestock, filed a lawsuit to block further

wolf releases. However, in 2000, a federal court upheld the

releases. By 2002, there were more than 150 wolves in the

park.

American timber wolves continued to be hunted and

trapped, legally and illegally, in their remaining refuges.

Alaska has periodically allowed and even promoted the aerial

hunting and shooting of wolves and has proposed plans to

shoot wolves from airplanes in order to increase the numbers

of moose and caribou for sport hunters. One such proposal

announced in late 1992 was postponed and then cancelled

after

conservation

and

animal rights

groups threatened

to launch a tourist boycott of the state.

In Minnesota, wolves are generally protected under

the federal

Endangered Species Act

, but

poaching

persists

because many consider wolves to be livestock killers. In 1978,

the wolves were reclassified from endangered to threatened,

which afforded them less protection. However, the U.S.

Fish

and Wildlife Service

(FWS) adopted a recovery plan in

1978 with the goal of increasing the Minnesota wolf popula-

tion to 1,400 by 2000. By 1999, the population was estimated

at 2,445 by the FWS although several

wildlife

groups be-

lieved the number was much less. Wolves were also success-

fully reintroduced into Wisconsin and Michigan, where the

population was estimated by the FWS at more than 100 in

1994. As of 2002, the FWS was considering delisting the

Minnesota wolf from protection under the Endangered Spe-

cies Act.

In Canada, they are frequently hunted, trapped, poi-

soned, and intentionally exterminated, sometimes to increase

the numbers of moose, caribou, and other game animals,

especially in the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia,

and the Yukon Territory. The maned wolf, (Chryocyon

brachyurus) is considered endangered throughout its entire

range of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Peru, and Uruguay. In

Norway, there were only 28 wolves in the wild as of 2002,

according to the

World Wildlife fund

. The number in Swe-

den was less than 100.

The most common type of wolf is the gray wolf (Canis

lupus) that includes the timber wolf and the Arctic-dwelling

tundra

wolf. The FWS lists the gray wolf as an endangered

species throughout its former range in Mexico and the conti-

nental United States, except in Minnesota, where it is

“threatened.” As many as 1,300 wolves may remain in the

wilds of Minnesota, 6,000–10,000 in Alaska, and thousands

more in Canada. A population ranging from one or two

dozen also lives on Isle Royale, Michigan.

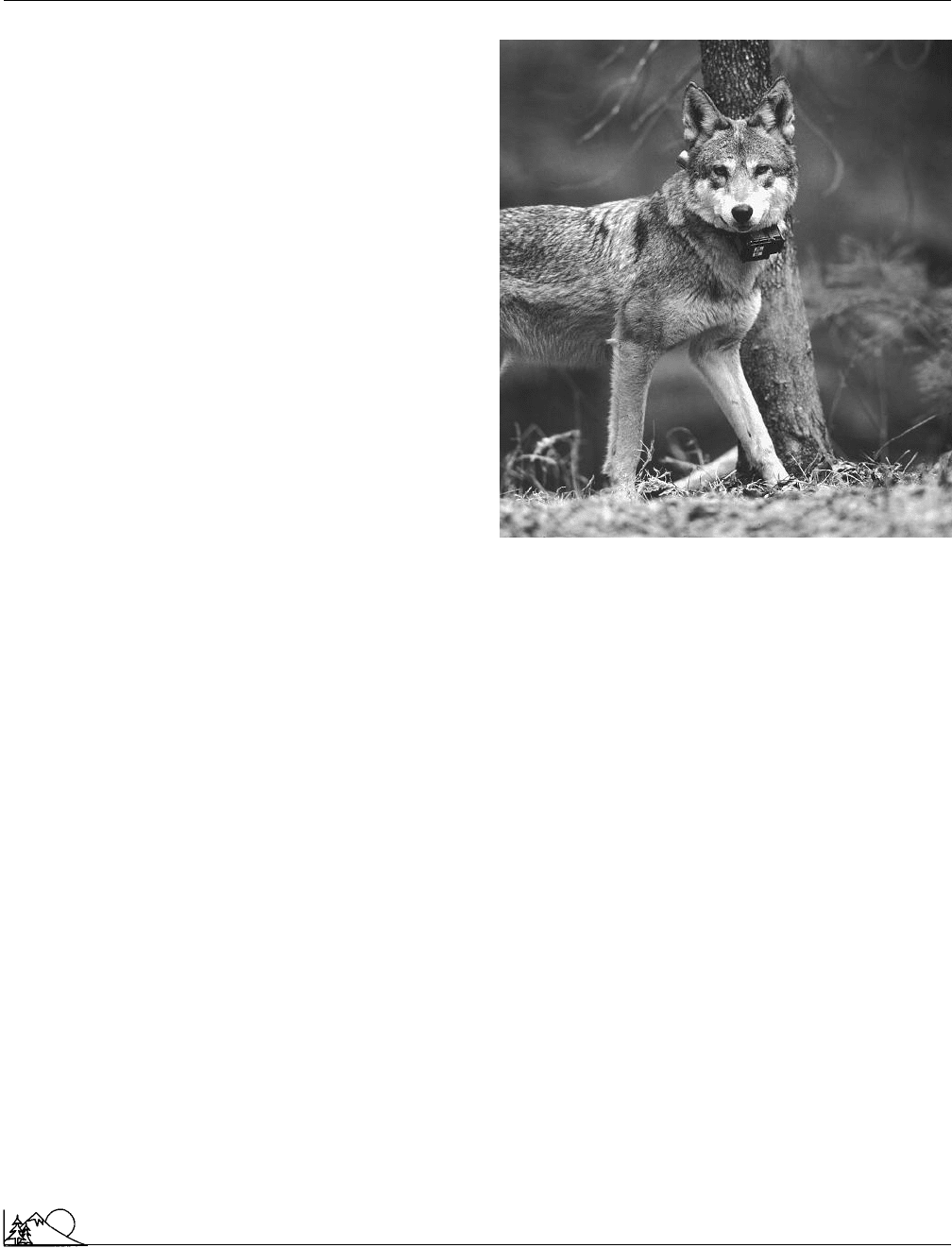

The red wolf (Canis rufus), a smaller type of wolf found

in the southeastern United States, was nearly extinct in the

wild when in 1970 the FWS began a recovery program.

With less than 100 red wolves in the wilds of Texas and

Louisiana, 14 were captured and became part of a captive

1531

Red wolf, Smoky Mountains National Park.

(Photography by Tim Davis. Photo Researchers Inc. Repro-

duced by permission.)

breeding program. By 2002, about 100 red wolves had been

reintroduced into the wilds in North Carolina, but are still

listed as Critical by the

IUCN—The World Conservation

Union

. A federal appeals court helped the effort when in

1970 it upheld FWS rules banning the killing of red wolves

that wander onto privately–owned land.

In 1998, the FWS reintroduced the Mexican wolf

(Canis lupus baileyi), a sub-species of the gray wolf, into the

Apache

National Forest

in Arizona after it had been gone

from the wild for 17 years. Two wolf families were released

but the reintroduction suffered setbacks when five of the

wolves were shot and killed by ranchers. The remaining

wolves were recaptured in 2002 and relocated to the Gila

National Forest and Gila

Wilderness

Area of New Mexico.

The FWS hopes to have reestablished 100 Mexican wolves

in the area by 2005. Less than 200 of the wolves survive in

captivity. The Mexican wolf was declared an

endangered

species

in 1976.

[Ken R. Wells]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Greenberg, Daniel A. Wolves. New York: Benchmark Books, 2002.

Martin, Patricia A. Fink. Gray Wolves. New York: Children’s Press, 2002.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

World Bank

Mech, L. David. The Wolves of Minnesota: Howl in the Heartland. Stillwater,

MN: Voyageur Press, 2000.

P

ERIODICALS

Clugston, Michael. “Intruding on Wild Lives.” Canadian Geographic (No-

vember–December 2001): 38.

“Defenders Applauds Decision to Translocate Mexican Wolves.” US New-

swire (March 22, 2000).

Holloway, Marguerite. “Wolves at the Door: Can We Learn to Dance

With Wild Things Again?” Discover (June 2000): 58.

Jones, Karen. “Fighting Outlaws, Returning Wolves.” History Today (March

2002): 38–41.

Knight, Deborah. “Uneasy Neighbors: Humans Evicted Wolves from Yel-

lowstone and Coyotes Moved In. Now the Wolves are Back.” Animals

(Spring 2002): 6–11.

O

RGANIZATIONS

International Wolf Center, 1396 Highway 169, Ely, MN USA 55731

(218) 365-4695, Email: wolfinfo@wolf.org, <http://www.wolf.org>

Woodpecker

see

Ivory-billed woodpecker

George Masters Woodwell (1928 – )

American ecologist

A highly respected but controversial

biosphere

ecologist

and biologist, Woodwell was born in Cambridge, Massachu-

setts. With his parents, who were both educators, Woodwell

spent most of his summers on the family farm in Maine,

where he was able to learn firsthand about biology,

ecology

,

and the

environment

.

Woodwell graduated from Dartmouth College in 1950

with a bachelor’s degree in zoology. Soon after graduation, he

joined the Navy and served for three years on oceanographic

ships. After returning to civilian life, he took advantage of

a scholarship to pursue graduate studies and earned both a

master’s degree (1956) and a doctorate (1958) from Duke

University. He began teaching at the University of Maine

and was later appointed a faculty member and guest lecturer

at Yale University. Throughout most of the 1960s and the

early 1970s, Woodwell worked as senior ecologist at the

Brookhaven National Laboratory. It was there that he con-

ducted the innovative studies on environmental

toxins

which earned him a reputation as a nonconformist ecologist.

In 1985, he founded the Woods Hole Research Center, a

leading facility for ecological research.

A pioneer in the field of biospheric

metabolism

,

Woodwell has worked to determine the effects of various

toxins on the environment. One of the many studies he

conducted examined the effects of

radiation exposure

on

forest ecosystems. He used a 14-acre (5.7 ha) combination

pine and oak forest as his testing area, and found that the

time needed to destroy an

ecosystem

is far less than that

1532

which is necessary to rejuvenate it. He continues to investi-

gate the effects of nuclear emissions on the environment.

Beginning in the 1950s, Woodwell worked with the

Conservation Foundation—now part of the World

Wildlife

Fund—in investigating the

pesticide

DDT. Woodwell and

his colleagues were the first to study the catastrophic effects

of the chemical on wildlife and, in 1966, were the first to

take legal action against its producers. DDT was banned in

the United States in 1972.

Much of Woodwell’s work has focused on the hazards

of the

greenhouse effect

. He has provided valuable infor-

mation for hearings on environmental issues, and has been

instrumental in developing similar data for the United States

and foreign government agencies. Not only is Woodwell

concerned about radiation,

chemicals

, and global warming,

but like

Paul Ehrlich

, he warns that

population growth

must be kept in balance with any ecosystem development.

While he does publish articles in professional journals,

Woodwell produces a number of works for more publications

with a broader audience. He considers it imperative that the

general population play a key role in saving the planet, and

his work has appeared in periodicals such as Ecology, Scientific

American, and the Christian Science Monitor.

Woodwell maintains membership in the

National

Academy of Sciences

and is a past president of the

Ecologi-

cal Society of America

. He is also a member of the

Environ-

mental Defense

Fund and

Natural Resources Defense

Council

. In 2001, Woodwell was awarded the Volvo Envi-

ronmental Prize.

[Kimberley A. Peterson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Gareffa, P. M., ed. Contemporary Newsmakers—1987 Cumulation. Detroit,

MI: Gale Research, 1988.

Woodwell, George M., ed. Earth in Transition: Patterns and Processes of

Biotic Impoverishment. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

———, et al. Ecological and Biological Effects of Air Pollution. New York:

Irvington, 1973.

P

ERIODICALS

Grady, D., and T. Levenson. “George Woodwell: Crusader for the Earth.”

Discover (May 1984): 44–6+.

Houghton, R. A., and G. M. Woodwell. “Global Climatic Change.” Scien-

tific American 260 (April 1989): 36–44.

Woodwell, George M. “On Causes of Biotic Impoverishment.” Ecology 70

(February 1989): 14–15.

World Bank

Affiliated with the United Nations, the World Bank was

formally established in 1946 to finance projects to spur the

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

World Bank

economic development of member nations, most notably

those in Europe and the

Third World

. The bank has been

strongly criticized by environmental and human rights

groups in recent years for funding Third World projects that

destroy rain forests, damage the

environment

, and harm

villagers and

indigenous peoples

.

The bank is headquartered in Washington, D.C. It is

administered by a board of governors and a group of executive

directors. The board of governors is composed principally

of the world’s finance ministers and convenes annually.

There are 21 executive directors who carry out policy matters

and approve all loans. The World Bank usually makes loans

directly to governments or to private enterprises with their

government’s guarantee when private capital is not available

on reasonable terms. Generally, the Bank lends only for

imported materials and equipment and services obtained

from abroad. The interest rate charged depends primarily

on the cost of borrowing to the Bank. The subscribed capital

of the bank exceeds $30 billion, and the voting power of

each nation is proportional to its capital subscription.

The 1970s represented a period of extensive growth

for the World Bank, both in the volume of lending and the

size of its staff. The staff was pressured to disperse money

quickly, and little real support for grassroots development

ever materialized within the institution. Local populations

were hardly ever consulted and rarely taken into account for

the majority of the enterprises the bank funded during this

period. As a result, billions of dollars of bank money was

managed ineffectively by domestic public institutions that

were often unrepresentative. The stated purpose of the loans

was to promote modernization and open economics, but the

lending network further supported the elite in the Third

World and prevented the poor from playing a meaningful

role in the policies that were so markedly reshaping their

environments.

The international debt crisis during this decade also

changed the bank, beginning its evolution into a debt-man-

agement institution when it lifted the restrictions on the non-

project lending that had been established by its founders. In

an effort to expedite its loan development, the bank under-

went a major reorganization in 1986. It consolidated its

activities under four senior vice presidents, but many consider

the net results of these changes to be far from successful.

The most notable critics of the World Bank have been

in the global environmental movement, but defects within

the bank’s operations complex have largely restricted their

campaigns from effecting major changes. The bank has re-

peatedly withheld the majority of the information it gener-

ates in the preparation and implementation of projects, and

many environmentalists continue to charge that it has be-

come an institution fundamentally lacking the accountability

and responsibility necessary for

sustainable development

.

1533

The way the World Bank handled the controversial

Narmada River Sandar Sarovar Dam project in India has

been called a case in point. According to the

Environmental

Defense

Fund, the history of bank involvement with the

project reveals an institution whose primary agenda is to

transfer money quickly, no matter what the cost in “system-

atic violation of its own environmental, economic and social

policies and deception of its senior management and Board

of Executive Directors.” United States Executive Director

E. Patrick Coady accused bank management and staff of a

cover-up in relation to the Sandar Sarovar Dam, and he

directly challenged the bank’s credibility, noting that “no

matter how egregious the situation, no matter how flawed

the project, no matter how many policies have been violated,

and no matter how dear the remedies prescribed, the bank

will go forward on its own terms.” Despite support from

Germany, Japan, Canada,

Australia

, and the Scandinavian

countries, Coady’s accusations were ignored. Bank manage-

ment continued to finance the dam until early 1993, when

criticism of the project became so intense that India decided

to finance the project itself. There was no plan to resettle

the 250,000 people who would be displaced.

Many argue that the failures of policies at the World

Bank are illustrated by other case studies in Brazil, Costa

Rica, and Ghana. In Brazil, International Monetary Fund

(IMF) stabilization programs have hit the poor particularly

hard and depleted the country’s

natural resources

. Al-

though these structural programs were designed to manage

Brazil’s tremendous foreign debt, critics argue they have

been socially, economically, and environmentally cata-

strophic. The “economic miracle” of the 1970s never materi-

alized for Brazil’s masses, despite the fact that the economy

grew more than any other country in the world between

1955 and 1980. Due largely to ill-conceived IMF and World

Bank advice, as well as ineffective leadership by the Brazilian

government, development decisions in Brazil have leaned

toward extravagant and poorly implemented projects. Many

major projects have failed miserably, only adding to lost

investments, and the environmental devastation caused by

such projects has been enormous, with much of it irreversible,

involving massive destruction of the

tropical rain forest

.

The Tucurui Dam project, for example, was part of

the Brazilian government’s plan to build some 200 new

hydroelectric power

dams

, most of them in the Amazonian

region. This project has destroyed thousands of acres of

tropical

rain forest

and degraded

water quality

in the

reservoir

and downstream, further lowering the income and

affecting the health of communities below the dam. For

environmentalists, Tucurui is representative of the problems

inherent in building large dams in tropical regions: “Opening

of forest areas leads to

migration

of landless people,

defor-

estation

of reservoir margins,

erosion

and

siltation

causing

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

World Bank

destruction of power-generating equipment and reduction

of its useful lifespan; spread of waterborne disease to human

and

wildlife

populations; and the permanent destruction of

fish and wildlife habitats, eliminating previously existing

local economic activity and unknown numbers of

species

of plants and animals.”

Ghana is usually touted by the World Bank and IMF

as a particularly successful example of structural adjustment

programs in Africa, but many believe that a closer examina-

tion reveals something different. The goal of the current

adjustment program was to reduce the fiscal deficit, inflation,

and external deficits by reducing domestic demand. A large

portion of this plan was “to reverse the decline in agricultural

production, restore overseas confidence in the Ghanian

economy, increase foreign-exchange earnings, restore ac-

ceptable living standards, control inflation, reform prices,

and reestablish production incentives for cocoa.” Although

cocoa production had increased 20% by 1988 as a result of

incentives in agricultural sector reform, with the income for

cocoa production increasing by as much as 700% in some

cases, cocoa farmers make up only 18% of Ghana’s farming

population. Furthermore, in recent decades a growing ineq-

uity within the cocoa-producing population has been docu-

mented. Half of the land cultivated for cocoa today is owned

by the top 7% of Ghana’s cocoa producers, while 70% own

farms of less than 6 acres (2.4 ha).

The timber industry in Ghana was also identified by

the IMF and World Bank as an additional source of foreign

exchange, and this led to the steady destruction of Ghana’s

forests. If timber production is maintained at its current

rate and without appropriate environmental controls, many

environmentalists and others believe that the Ghanian coun-

tryside will be stripped bare by the year 2000. The fishing

industry is also threatened. Rising costs have caused the

price of fish to increase while real wages have fallen. Gha-

nians receive 60% of their protein from the products of ocean

fisheries, and decreased fish consumption in considered one

of the leading factors in the rise of malnutrition in the

country.

While mounting public pressure might cause the bank

to reconsider some of its programs, reforms are possible only

if supported by those nations controlling more than half of

the Bank’s voting shares. And no matter what direction is

taken, many experts believe that internal contradictions will

continue to trouble the bank for years, further lowering the

morale of the staff. As long as the bank continues to place

priority on its debt-management functions, it will likely fail

to change its policy of making large-scale loans for question-

able and destructive projects. Overall quality may be further

diminished as developing nations continue to give up natural

resources for the rapid earning of foreign exchange. Debt

management could then force the bank to support large-

1534

scale, poorly-organized, and poorly-supervised projects,

while the staff would be pressed harder to address wider

development problems that could continue to be exacerbated

by other aspects of bank lending.

The World Bank’s dismal record of ignoring the inter-

ests of the poor and the environment clearly raises funda-

mental questions about the future of the institution. Envi-

ronmentalists, human rights groups, and other critics of the

Bank have offered the following suggestions for improving

its operations. While there are obvious reasons for keeping

some information confidential, they argue, the bank has

abused this right. Greater freedom of information is neces-

sary because participation with population groups in the

development process is impossible without public access.

Critics also argue for the establishment within the Bank of

an independent appeals commission, maintaining that there

is a clear need for a body that would hear and act on com-

plaints of environmental and social abuses. It has been sug-

gested that this commission could be made up of environ-

mentalists, academics, church representatives, human rights

groups, and others who would encourage the bank to empha-

size sustainable development and eliminate environmentally

destructive projects. And finally, it has been widely suggested

that project quality should be the first priority of the World

Bank, with the United Nations taking the lead in demanding

this. In short, many believe the bank should no longer be

allowed to function as a money-moving machine to address

macro-economic imbalances. See also Economic growth and

the environment; Environmental economics; Environmental

policy; Environmental stress; Green politics; Greens; United

Nations Earth Summit; United Nations Environment Pro-

gramme

[Roderick T. White Jr.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Le Prestre, P. G. The World Bank and the Environmental Challenge. London:

Associated University Presses, 1989.

P

ERIODICALS

Payer, C. The World Bank: A Critical Analysis. New York: Monthly Review

Press, 1982.

World Commission on Environment

and Development

see Our Common Future

(Brundtland

Report)

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

World Resources Institute

World Conservation Strategy

The World Conservation Strategy (WCS): Living Resource

Conservation for Sustainable Development is contained in

a report published in 1980 and prepared by the International

Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources

(now called

IUCN—The World Conservation Union

). As-

sistance and collaboration was received from the

United

Nations Environment Programme

(UNEP), the

World

Wildlife Fund

(WWF), the Food and Agriculture Organiza-

tion of the United Nations (FAO), and the United Nations

Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

(

UNESCO

).

The three main objectives of the WCS are: (1) to

maintain essential ecological processes and life-support sys-

tems on which human survival and development depend.

Items of concern include

soil

regeneration and protection,

the

recycling

of nutrients, and protection of

water quality

;

(2) to preserve genetic diversity on which depend the func-

tioning of many of the above processes and life-support

systems, the breeding programs necessary for the protection

and improvement of cultivated plants, domesticated animals,

and

microorganisms

, as well as much scientific and medical

advance, technical innovation, and the security of the many

industries that use living resources; (3) to ensure the sustain-

able utilization of

species

and ecosystems which support

millions of rural communities as well as major industries.

The WCS believes humans must recognize that the

world’s

natural resources

are limited, with limited capaci-

ties to support life, and must consider the needs of

future

generations

. The object, then, is to conserve the natural

resources, sustain development, and to support all life. Hu-

mans have great capacities for the creation of wants or needs

and also have great powers of destruction and annihilation.

Human action has global consequences, and thus global

responsibilities are crucial. The aim of the WCS is to provide

an intellectual framework as well as practical implementation

guidelines for achieving its three primary objectives.

The WCS has been endorsed by numerous leaders,

organizations, and governments, and has formed the basis

for preparation of National Conservation Strategies in over

fifty countries.

The World Conservation Monitoring Centre

(WCMC) mission is to support conservation and sustainable

development by providing information on the world’s

bio-

diversity

. It is a joint venture between the three main coop-

erators of WCS, IUCN, UNEP, and WWF.

The WCS has been supplemented and restated in a

document called Caring for The Earth: A Strategy for Sustain-

able Living, published in 1991. This document restates cur-

rent thinking about conservation and development and sug-

gests practical actions. It establishes targets for change and

1535

urges a concerted effort in personal, national, and interna-

tional relations. It stresses measuring achievements against

the objectives of actions.

The WCS of 1980 and the 1991 update have done

much to bring attention to the need for sustainable manage-

ment of the world’s natural resources. It outlines problems,

suggests needed changes, and stresses the need to quantitate

the progress in meeting the needs of a sustainable world.

See also Environmental education; Environmental ethics;

Environmental monitoring; Sustainable biosphere

[William E. Larson]

R

ESOURCES

O

THER

Caring for the Earth: A Strategy for Sustainable Living. Gland, Switzerland:

IUCN—The World Conservtion Union, 1991.

World Conservation Strategy. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for

the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 1980.

World Resources Institute

An international environmental and resource management

policy center, the World Resources Institute researches ways

to meet human needs and foster economic growth while

conserving

natural resources

and protecting the

environ-

ment

. WRI’s primary areas of concern are the economic

effects of environmental deterioration and the demands on

energy and the environment

posed by both industrial and

developing nations. Since its inception in 1982, WRI has

provided governments, organizations, and individuals with

information, analysis, technical support, and policy analysis

on the interrelated areas of environment, development, and

resource management.

WRI conducts various policy research programs and

operates the Center for International Development and En-

vironment, formerly the North American arm of the Interna-

tional Institute for Environment and Development. The

institute aids governments and nonfederal organizations in

developing countries, providing technical assistance and pol-

icy recommendations, among other services. To promote

public education of the issues with which it is involved, WRI

also publishes books, reports, and papers; holds briefings,

seminars, and conferences; and keeps the media abreast of

developments in these areas.

WRI’s research projects include programs in biological

resources and institutions; economies and population;

cli-

mate

, energy, and

pollution

; technology and the environ-

ment; and resource and environmental information. In col-

laboration with the Brookings Institution and the Santa Fe

Institute, WRI is also involved in a program called the

2050 Project, which seeks to provide a sustainable future for

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

World Trade Organization (WTO)

coming generations. As part of the program, studies will be

conducted on such topics as food, energy,

biodiversity

, and

the elimination of poverty.

The Center for International Development and Envi-

ronment assists developing countries assess and manage their

natural resources. The center’s four main programs are: natu-

ral resources management strategies and assessments; natural

resource information management; community planning and

nongovernmental organization

support; and sectoral re-

source policy and planning.

WRI’s other programs are equally innovative. As part

of the Biological Resources and Institutions project, WRI

has developed a Global Biodiversity Strategy in collaboration

with the World Conservation Union and the

United Na-

tions Environment Programme

. The strategy, developed

in 1992, outlines 85 specific actions required in the following

decade to slow the decline in biodiversity worldwide. The

program has also researched ways to reform forest policy in

an attempt to halt

deforestation

.

The program on climate, energy, and pollution strives

to develop new and different

transportation

strategies. In

so doing, WRI staff have explored the use of hydrogen- and

electric-powered vehicles and proposed policies that would

facilitate their use in modern society. The program also

researches renewable

alternative energy sources

, includ-

ing solar, wind, and

biomass

power.

WRI is funded privately, by the United Nations, and

by national governments. It is run by a 40-member interna-

tional Board of Directors.

[Kristin Palm]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

World Resources Institute, 10 G Street, NE, Suite 800, Washington, D.C.

USA 20002 (202) 729-7600, Fax: (202) 729-7610, Email: front@wri.org,

<http://www.wri.org>

World Trade Organization (WTO)

In December, 1999, the streets of Seattle, Washington, filled

with billowing clouds of tear gas and pepper spray as squad-

rons of police in full riot gear skirmished with surging masses

of protestors in the most confrontational political demon-

strations in the United States in nearly three decades. The

angry crowds were there to confront delegates from 135

member nations of the World Trade Organization (WTO)

who were meeting to hammer out an agenda for the next

round of negotiations to regulate international trade.

Few people in America had ever heard of the WTO

before the historic protest in Seattle, and yet, this exclusive

body has power that affects us all. Created in 1995 by an

1536

international treaty, the WTO is the successor to the General

Agreement on Tariffs and Grade (GATT), established at

the end of the World War II to eliminate tariffs and trade

barriers. Both GATT and WTO are part of the Bretton

Woods system (named after the location in New Hampshire

where the system was established in 1944) that includes the

World Bank

group and the International Monetary Fund

(IMF). Where GATT was limited to considering economic

issues, however, the scope of the WTO has been expanded

to “noneconomic trade barriers” such as food safety laws,

quality standards, product labeling, workers rights, and envi-

ronmental protection standards. With legal standing equiva-

lent to the United Nations, the WTO operates largely in

secret. When considering trade disputes, it meets behind

closed doors based on confidential evidence.

WTO judges are trade bureaucrats, usually corporate

lawyers with ties to the industries being regulated. There

are no rules against conflicts of interest, nor are there require-

ments that judges know anything about the culture or cir-

cumstances of the countries they judge. No appeal of WTO

rulings is allowed. A country that loses a trade dispute has

three options: (1) amend laws to comply with WTO rules,

(2) pay annual compensation—often millions of dollars—to

the complainants, or (3) face nonnegotiable trade sanctions.

Critics claim that the WTO always serves the interest of

transnational corporations and the world’s richest countries.

Among the most controversial issues brought up in

this round of WTO negotiations are agricultural subsidies,

child labor laws, occupational health and safety standards,

protection of intellectual property, and environmental stan-

dards. Environmentalists, for example, were outraged by a

1998 WTO ruling that a U.S. law prohibiting the import

of shrimp caught in nets that can entrap

sea turtles

is a

barrier to trade. The United States must either accept shrimp

regardless of how they are caught, or face large fines. Some

other WTO rulings that overturn environmental or con-

sumer safety laws require Europeans to allow importation

of U.S. hormone-treated beef, Americans must accept tuna

from Mexico that endangers

dolphins

, and the U. S.

Envi-

ronmental Protection Agency

(EPA) cannot bar import

of low-quality

gasoline

that causes excessive

air pollution

.

In some pending cases, Denmark wants to ban 200

lead

compounds in consumer products; France wants to prohibit

asbestos

; and several countries want to eliminate electronic

devices containing lead,

mercury

, and

cadmium

. Under

current WTO rules, all these cases probably will be ruled

illegal.

More than 50,000 people came to Seattle from all over

the world to show their displeasure with the WTO. French

farmers, Zapatista rebels from Mexico, Tibetan refugees,

German anarchists, First Nations people from Canada, labor

unionists, environmentalists in turtle suits,

animal rights