Elsevier Encyclopedia of Geology - vol I A-E

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Further Reading

Ashley PM and Flood PG (eds.) (1997) Tectonics and

Metallogenesis of the New England Orogen. Special

Publication 19. Sydney: Geological Society of Australia.

Birch WD (ed.) (2003) Geology of Victoria. Special

Publication 23. Sydney: Geological Society of Australia.

Burrett CF and Martin EL (eds.) (1989) Geology and Min-

eral Resources of Tasmania. Special Publication 15.

Sydney: Geological Society of Australia.

Coney PJ, Edwards A, Hine R, Morrison F, and Windrum D

(1990) The regional tectonics of the Tasman orogenic

system, eastern Australia. Journal of Structural Geology

125: 19–43.

Flo

¨

ttmann T, Klinschmidt D, and Funk T (1993)

Thrust patterns of the Ross/Delamerian orogens in

northern Victoria Land (Antarctica) and southeastern

Australia and their implications for Gondwana

reconstructions. In: Findlay RH, Unrug R, Banks HR,

and Veevers JJ (eds.) Gondwana Eight, Assembly,

Evolution and Dispersal, pp. 131–139. Rotterdam:

Balkema.

Foster DA and Gray DR (2000) The structure and evo-

lution of the Lachlan Fold Belt (Orogen) of eastern

Australia. Annual Reviews of Earth and Planetary

Sciences 28: 47–80.

Foster DA, Gray DR, and Bucher M (1999) Chronology

of deformation within the turbidite-dominated Lach-

lan orogen: implications for the tectonic evolution

of eastern Australia and Gondwana. Tectonics 18:

452–485.

Gray DR and Foster DA (1997) Orogenic concepts –

application and definition: Lachlan fold belt, eastern

Australia. American Journal of Science 297: 859–891.

Scheibner E and Basden H (eds.) (1998) Geology of

New South Wales—Synthesis. Volume 2: Geological

Evolution. Memoir Geology 13(2). p. 666. Sydney: Geo-

logical Survey of New South Wales.

Veevers JJ (ed.) (1984) Phanerozoic Earth History of

Australia. Oxford Monographs on Geology and Geo-

physics 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Veevers JJ (ed.) (2000) Billion-year Earth History of

Australia and Neighbours in Gondwanaland. Sydney:

GEMOC Press.

AUSTRALIA/Tasman Orogenic Belt 251

BIBLICAL GEOLOGY

E Byford, Broken Hill, NSW, Australia

ß 2005, Elsevier Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

World-View of the Hebrew Scriptures

The world-view of those who wrote or edited the

Hebrew Scriptures reflects the commonly held

contemporary understandings of the structure of

the universe. The editors of the Hebrew Scriptures

(including those who wrote the first chapter of

the Book of Genesis) did their work in the period

immediately following the end of Babylonian exile.

The return from exile followed the conquest of

Babylon by Cyrus, King of Persia, in 538 bce. The

world-view in the scriptures was that of the desert

people who lived in the Fertile Crescent of modern

Iran, Iraq, Syria, Israel, and Jordan. The clearest,

detailed articulation of the structure of the world

and the universe is to be found in the Book of Job,

Chapters 38–40.

What is described in Genesis 1:1 to 2:3 was the

commonly accepted structure of the universe from

at least late in the second millennium bce to the

fourth or third century bce. It represents a coherent

model for the experiences of the people of Mesopota-

mia through that period. It reflects a world-view that

made sense of water coming from the sky and the

ground as well as the regular apparent movements

of the stars, sun, moon, and planets. There is a clear

understanding of the restrictions on breeding be-

tween different species of animals and of the way in

which human beings had gained control over what

were, by then, domestic animals. There is also re-

cognition of the ability of humans to change the

environment in which they lived. This same under-

standing occurred also in the great creation stories of

Mesopotamia; these stories formed the basis for the

Jewish theological reflections of the Hebrew Scrip-

tures concerning the creation of the world. The

Jewish priests and theologians who constructed the

narrative took accepted ideas about the structure of

the world and reflected theologically on them in the

light of their experience and faith. There was never

any clash between Jewish and Babylonian people

about the structure of the world, but only about

who was responsible for it and its ultimate theological

meaning.

The envisaged structure is simple: Earth was seen as

being situated in the middle of a great volume of

water, with water both above and below Earth.

A great dome was thought to be set above Earth

(like an inverted glass bowl), maintaining the water

above Earth in its place. Earth was pictured as resting

on foundations that go down into the deep. These

foundations secured the stability of the land as some-

thing that is not floating on the water and so could

not be tossed about by wind and wave. The waters

surrounding Earth were thought to have been

gathered together in their place. The stars, sun,

moon, and planets moved in their allotted paths

across the great dome above Earth, with their move-

ments defining the months, seasons, and year.

In the world of the Jewish scribes and priests who

assembled the Hebrew Scriptures, the security of the

world (the universe) was ‘guaranteed’ by God. It was

God who made the world secure. It was God who

made Earth move or not move, as the case might be.

When this is understood, the ancient sources can

be understood, and many of the geological events

that produced the theological reflections can be

deciphered.

Geological Events with References in

the Hebrew Scriptures

The Angel with the Flaming Sword (Genesis 3:24)

The location of the Garden of Eden was described as

being ‘‘in the east’’. Four rivers were said to have

flowed out of Eden. The naming of the Tigris, the

Euphrates, and two other streams that have names

that translate literally from the Hebrew to ‘gusher’

and ‘bubbler’ suggests that the garden was located

at the top of the Persian Gulf. This area is well

watered and would have been lush compared to the

desert area that was the habitual location of the

Jewish people from the beginning of the first millen-

nium bce.

The creatures with flaming sword are described as

cherubim. In the ancient world, these were supposed

awesome (hybrid) creatures and were the steeds that

carried the high god of the Canaanites through the air.

What is interesting is that the reference to the sword

was made using the definite article, as if ‘it’ (whatever

it was) were well known. This is a region well known

for its petroleum deposits and oil and gas fires. A gas

release or petroleum seep that caught fire could last

for many years and extend hundreds of metres above

the ground. It would have released much light, heat,

and sound and would have been of the very nature

described in the Biblical text as keeping people away

from the locality.

BIBLICAL GEOLOGY 253

The Flood: Genesis 6–9

Since, at latest, the middle of the nineteenth century,

scholars, both scientific and theological, have rejected

as impossible the idea of a flood that inundated all of

Earth’s landmasses. The flood story has been treated

as ancient myth or as a theological metaphor for the

return to supposed primeval chaos as a consequence

of human sin. It can also be regarded as an expansion

of local flood stories from the flood plains of great

rivers and coastal areas to some sort of universal

status. But since the work of William Ryan and

Walter Pitman, there has been renewed interest in

the occurrence of a catastrophic flood.

At the time of maximum glaciation at the height of

the last Ice Age (about 16 000 bce), sea-levels were

about 120 m lower than present levels are. There was

no longer a connection between the Black Sea Basin

and the Mediterranean Sea. With the first great

melting of the Eurasian Ice Sheet (12 500 bce), the

Black Sea filled with fresh water, which flowed

through the Sakarya Outlet into the Sea of Marmara

and down the Dardanelles Outlet into the Aegean.

Later, with only seasonal flows down the rivers feed-

ing the Black Sea, the level of this body of water

fell far below its great melt maximum. But the level

of the Mediterranean, connected to the waters of the

world’s oceans, continued to rise over the next

6000 years while at the same time the former channels

from the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara filled with

rubble, thus creating a dam between the Mediter-

ranean and the Black Sea Basin. By 6000 bce, the

sea-level in the Mediterranean was at least 100 m

higher than the surface of the great Black Sea fresh-

water lake.

Ryan and Pitman have proposed a single geological

event, namely, the breaching of that dam through

what is now the Bosphorus Straight, from which

followed the sudden and catastrophic flooding of

the Black Sea Basin with salt water. Ryan and Pitman

date the disappearance of freshwater molluscs and

the introduction of saltwater molluscs to 5600 bce.

This happened suddenly, not gradually. Their sub-

marine survey work has indicated that the Bosphorus

was eroded by immense flows from the Mediterra-

nean to the Black Sea. The inclination of the channel

towards the Black Sea also accounts for the surface

current of relatively fresh water towards the Mediter-

ranean Sea and the lower more saline current directed

towards the Black Sea. The dating of this geological

event to early agricultural times links it to the Noah/

Gilgamesh story.

There is some controversy in the early twenty-first-

century geology literature concerning Ryan and Pit-

man’s hypothesis of a single catastrophic breaching

of the Bosphorus. At the time of publication, that

controversy continues. However, Ryan and Pitman’s

hypothesis is not based simply on the dating of

marine molluscs, but significantly on the erosion pro-

files of the Bosphorus Channel. These profiles reveal

the continuation of the erosion channel beyond the

escarpment, well below present sea-levels.

Most flood stories came from areas of flood plains

and coastal districts and can be related to the sea-level

rises associated with the end of the last Ice Age (10 000

to 12 000 years ago). The Noah legend is significantly

different from these in that it is associated with the

Anatolian highlands, well away from the coast and

well above sea-level. The Black Sea had been a salt-

water sea, but had become a large freshwater lake.

Following the last Ice Age, it then shrank to become a

lake with a surface about 100 m lower than the pre-

sent level, but suddenly filled and became salty at

about 5600 bce. More recent discoveries by Robert

Ballard indicate that there were quite sophisticated

settlements on the shore of the freshwater lake before

the reintroduction of salt water. These settlements

seem to have been built on well-established agricul-

tural and animal husbandry practices. Ryan and

Pitman estimate that, after the breach of the Bosphorus,

water would have flowed into the Black Sea Basin at

about 40 km

3

day

1

and that the water level would

have risen by about 15 cm day

1

.Theyestimatethat

the sound of the great inrush could have been heard up

to nearly 500 km away. The water would have surged

down the escarpment accompanied by large volumes of

spray and deafening noise.

According to the Genesis account of the flood

(Genesis 6–8), Noah was warned of the impending

disaster and was told to make preparations for the

preservation of animal and plant stock, which were to

be preserved and transported to safety by means of a

vessel that Noah was to build. The flood is described

as coming from the sky and from the deep (Genesis

7:11). Noah had time to make the necessary prepar-

ations to save his domestic breeding and seed stock,

for it would have taken nearly two years to fill the

Black Sea Basin. In the flat country on the northern

shores of the old freshwater lake, the advance of

shoreline would have been about 1 km day

1

. The

legend could well refer to an actual historical event,

because people could have known of the rising water

level on the Mediterranean side of the Bosphorus

barrier, prior to its rupture.

It is suggested that those who fled the Black Sea

Basin went in all directions, into northern and west-

ern Europe, and, significantly, across the Anatolian

Plateau (adjacent to the location of the mountains

of Ararat), into the Fertile Crescent, where the

newcomers introduced their more sophisticated

254 BIBLICAL GEOLOGY

agricultural practices and preserved the story of the

destruction of their world in the great flood.

The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (Genesis

19 : 24–26)

The description of the destruction of the Sodom and

Gomorrah, two cities on the Plain, contains signifi-

cant elements that correspond to massive earthquakes

and the opening of sulphurous springs. Traditionally,

Sodom and Gomorrah have been thought to have

been located in the valley of the Dead Sea, perhaps

even where the Dead Sea is now located. In spite of

clear suggestions of a catastrophic geological event,

no particular event has been satisfactorily identified

with this story, nor have any identifiable ruins of early

second-millennium-bce towns or cities been found.

Thus the description stands, but a particular event or

location remains a matter of conjecture.

The Exodus

The Crossing of the Red Sea—Two Stories in

Exodus 14 There are two accounts of the crossing

of the Red Sea (the Hebrew name of which can also

be translated as ‘Sea of Reeds’ or ‘Distant Sea’)in

Chapter 14 of the Book of Exodus. The accounts

are intricately intertwined but refer to two readily

identifiable and distinguishable phenomena. It is

generally agreed that the route of the Exodus from

Egypt into the Sinai was close to the northern end of

the Red Sea.

The first of these phenomena concerned the action

of steady, strong winds on shallow expanses of water.

Water can be removed a long way from the normal

shoreline of one side of a lake or inlet, for the dur-

ation of the wind, and can then return to normal

levels when the wind subsides. (This is a commonly

observed phenomenon at Lake George, Australia,

near Canberra.) At the beginning of the first account

of the crossing (Exodus 14:21), we are told ‘‘the Lord

drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night, and

made the sea dry land’’. This account then tells of the

attempt of the Egyptians to follow through after the

Hebrews and that their chariot wheels became

clogged and they fled. When it is recognized that the

Hebrews had herds and were mostly on foot and

would have further softened ground that was usually

under water, then the clogging of the wheels of char-

iots would be expected. The dropping of the wind and

the return of the water could have been a perfectly

natural phenomenon.

The second account is much more dramatic, with

references to great walls of water (Exodus 14:22).

The destruction of the Egyptians was said to have

been accomplished by the catastrophic return of the

water (Exodus 14:28). This second account is of a far

more destructive phenomenon, compared to the first,

and probably more familiar one. In the second

account, the sea pulls back and then surges over

those who have ventured onto the ground from

which the sea receded. This is a classic description of

the destruction wrought by a tsunami.

The dating of the events of the Exodus has never

been exactly agreed by scholars. The generally agreed

range of dates is from the fifteenth century bce to the

middle of the thirteenth century bce. Near the begin-

ning of this period, there was, in fact, an event that

could have produced a catastrophic tsunami of the

type described in Exodus. In 1470 bce, the volcano

Santorini erupted with about the same force as that of

Krakatau in 1883. These eruptions are the largest in

historical times. The tsunami resulting from the San-

torini eruption wrought havoc in northern Crete and

on Milos and in the Peloponnese. This same tsunami

would have swept south, causing immense damage

along the Egyptian coast and especially in the low-

lying agricultural areas of the Nile Delta. The sea

would have withdrawn, possibly for 15 or 20 min,

and then would have come the first return wave.

The wave that hit Milos had a height of about

100 m and travelled at about 300 km h

1

. Even at

half this speed and height, the destruction in Egypt

would have been immense. Such an event would have

been associated with the gods, and, for the Hebrews,

with their own God. Thus, in Exodus 14, the ac-

counts are of a real catastrophic event and of another

event, of more common experience, combined into a

single story of the power of the Hebrew God to save

the Hebrew people.

The Plagues (Exodus 7–11) Evidence from the

Greenland ice sheets implies that the Santorini erup-

tion generated high levels of sulphuric acid. There

would have been sustained acid rain in the eastern

Mediterranean and cooling for many years as result

of the dust blasted into the atmosphere. There would

have been initial crop failures as a result of the acid

rain and continued low yields as a result of lower

temperatures. The dust blasted into the high atmos-

phere would have darkened the sky, making the sun

and moon appear red, perhaps for several years.

Acid rain would also have contaminated water,

causing destruction of aquatic plants and fishes. If

this were combined with significant ash-falls, the

waterways could have been rendered anoxic for a

considerable length of time. Moreover, contaminated

water and acid rain, with sudden loss of pasture,

would be associated with a rise in stock disease and

invasion of settled areas by insects and other vermin

in search of food sources.

BIBLICAL GEOLOGY 255

In the plague stories, descriptions of agricul-

tural phenomena are consistent with the effects

that would have followed the Santorini eruption.

The sequence of plagues in Exodus were as follows:

(1) blood (the Nile turns to ‘blood’ and everything in

it died), (2) frogs, (3) gnats, (4) flies, (5) livestock

disease, (6) boils, (7) hail and thunderstorms, (8) lo-

custs, (9) darkness, and (10) death of the first-born

child. Except for the last (which is clearly related to

Jewish religious and cultic practice), each of the

plagues could have been caused by the eruption of

Santorini. Whatever else is concluded, it is clear that

phenomena that would have been consequences of the

eruption of Santorini were associated directly, in the

stories and literature of the Hebrews, with the sup-

posed divine intervention that led to the Exodus.

The Crossing of the River Jordan (Joshua 3–4) The

crossing of the Jordan on dry land, by Joshua and

descendants of those who had fled Egypt, is said to

have been accomplished as a result of the waters

‘‘rising up in a single heap far off at Adam, the city

that is beside Zarethan’’ (Joshua 3:16). Adam is at the

junction of the Jordan and Jabbok rivers, about

25 km north (upstream) of the closest crossing point

of the Jordan to Jericho. The Dead Sea/Jordan Valley

is part of geologically active rift system where the

Eurasian and African plates interact. Movements

along the fault system could have produced a rubble

dam that blocked the flow of the Jordan, as described

in Joshua, thus allowing a crossing on dry ground or

through very shallow water.

The Tablets of Stone with the Law Inscribed on

Them The Ark of the Covenant, containing the

tablets of stone that Moses brought down from

the mountain, was the significant agent in the story

of the Jordan crossing. The tablets were understood

to have been given to Moses after God inscribed the

law on them. The story of the initial giving of the

tablets is in a series of events described in Exodus

24:12 and 31:18. The breaking of the stones is de-

scribed in Exodus 32:19 and the giving of new stones

is told in Exodus 34.

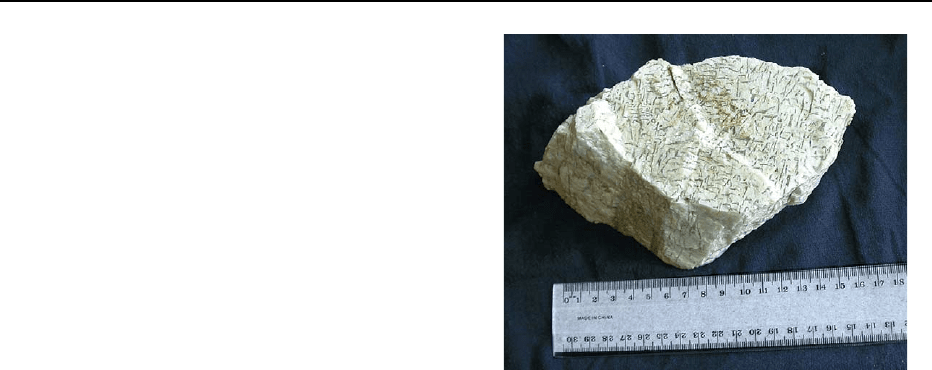

There is Precambrian graphic granite in the south-

ern Sinai, the rock being formed by an intergrowth of

quartz in feldspar derived from a quartz–feldspar

melt, which gives the appearance of writing in stone

(see Figure 1). Tablets of this material can be up to 20

by 20 cm. They are brittle, and when dropped, they

cleave along the plane of crystallographic weakness.

Moses Strikes the Stone to Produce Water: Exodus

17:1–7 The regions associated with the wanderings

of the Exodus are in the Sinai Peninsula, south of the

Dead Sea and in the approach to the Holy Land on the

eastern side of the Dead Sea and the Jordan. The river

was crossed from the east and the siege of Jericho

began. To the south and east of the Dead Sea, there

are permeable sandstones overlaying impermeable

granites. Water seeps down through the sandstones

until it reaches the impermeable granite. Where there

are vertical fractures, springs occur where water

emerges from the rock face to produce a rock pool.

A sequence of such springs occurs along the edge of

the formations. One such pool, Wadi Musa (in

modern Jordan), is identified by the local Bedouin

with the story of Musa (Moses) striking the rock to

get water.

References to Earth Movements

The Hebrew and Christian scriptures originated at

the eastern end of the Mediterranean, a region of

geological activity throughout historical times. God

was described as both securing the stability of the

earth (Psalms 93 and 96) or as shaking the earth

(Isaiah 29). God thus both protected people from

earthquakes and caused them.

Earthquakes were used to indicate dates (e.g.,

Amos 1:1; Zechariah 14:5). Zechariah 14:5 referred

back to the Amos earthquake (middle of the eighth

century bce), but the whole passage (Zechariah

14:4, 5) described what may now be construed as the

lateral shift caused by an earthquake near Jerusalem.

The Mount of Olives tear/wrench fault is part of the

complex of tear faults that form the Dead Sea/Jordan

Valley. In these regions, the rocks on the western side

of the valley are displaced southwards compared to

those on the east.

Figure 1 Example of graphic granite (from Thackaringa Hills,

west of Broken Hill, NSW, Australia). Photograph by Edwin Byford.

256 BIBLICAL GEOLOGY

The Scientific Revolution Beginning in

the Sixteenth Century, and Christian

Responses Thereto

For a convenient point of departure, the beginning

of the scientific revolution can be taken to be with

Nicolas Copernicus (1473–1543), who, while a

canon of Frauenburg (1497–1543), formulated a

model of the solar system with the sun, not Earth, at

its centre. It is commonly accepted that Copernicus

was responsible for the seminal ideas that laid the

foundations of the work of Kepler, Galileo, and

Newton. In spite of great reservations about the new

learning (note the condemnations of Galileo and the

fact that the work of Copernicus remained on the

Index from 1616 to 1757), Pope Gregory XIII revised

and corrected the calendar in 1582, following advice

from the Vatican Observatory. Although Protestant

countries did not adopt the revisions for some centur-

ies (in England and the American colonies not until

1752, and in the eastern Orthodox countries not

until 1924), the Gregorian calendar is now the

accepted norm.

Seventeenth-century England saw the theoretical

foundations for modern science established in the

work of Isaac Newton (1642–1727). But it was seven-

teenth-century Britain that also produced what has

become the centrepiece of a perceived clash of sci-

ence, and especially geology, and Christianity. In the

politically and religiously charged atmosphere of

the Protectorate, James Us(s)her (1581–1656), who

was a graduate of Trinity College, Dublin, and Arch-

bishop of Armagh, calculated the age of Earth, using

the ages of the Patriarchs as they were recorded in the

Old Testament, and interlocking these dates with

those available from the great civilisations of the

ancient world. His calculations were given in his

Annales Veteris et Novi Testamenti, written between

1650 and 1654. Ussher dated the creation of Earth at

23 October 4004 bc. From 1679, Ussher’s dates for

various events were included as marginal notes in the

‘Oxford Bibles’ and in modified form in subsequent

editions of the Authorised Version of the Bible (the

‘Lloyd Bible’, 1701), thereby establishing Ussher’s

dates in the minds of those who read the Bible in

English.

By the eighteenth century, a mechanistic under-

standing of the universe was accepted among theolo-

gians and church leaders, especially in Britain and the

Protestant maritime nations. Studies in botany, zo-

ology, and anatomy, as well as the developments in

mechanics and astronomy, provided data for argu-

ments for the existence of God based on ideas of

divine design. William Paley (1743–1805) published

his Natural Theology (1802), which remained a basic

text in apologetics until well into the twentieth cen-

tury. The newly emerging sciences were understood to

provide further proof concerning the existence and

benevolent nature of God. The convergence of science

and Christian faith was further encouraged by en-

dowments such as that by Robert Boyle (1627–91),

of Boyle’s Law fame, for annual lectures on Christian

apologetics. As yet, there was little to bring Ussher’s

date of the creation of Earth into question.

All this began to change from the middle of

the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, with

the beginnings of the classifications of fossils and

sedimentary strata. For some decades, accommo-

dation of Christian faith and the emerging pool of

geological data and interpretation was achieved

(more or less) through what has been called ‘flood

geology’, based chiefly on the ‘catastrophist’ ideas of

the Frenchman Georges Cuvier (see Famous Geolo-

gists: Cuvier). But by the middle of the nineteenth

century, this was no longer accepted in learned scien-

tific or theological circles. Following on the work of

James Hutton (see Famous Geologists: Hutton), the

influential geologist Charles Lyell (1830) (see Famous

Geologists: Lyell) argued for noncatastrophist geol-

ogy and, using evidence from his work at Mount

Etna and elsewhere, for the idea that Earth was

immensely old.

Many clergy, especially in England and Scotland,

had been in the forefront of the new biological and

geological sciences. But this did not prepare them for

the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species

(1859) (see Famous Geologists: Darwin). The cre-

ation of the world was pushed back thousands of

millions of years, and human beings could no longer

be understood as a unique creation, qualitatively dif-

ferent from all other life forms. Though many scien-

tists, including William Thomson (Lord Kelvin),

questioned the extreme age of Earth advocated by

Lyell and Darwin, it was certain clergy, most notably

Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford, who attacked

Darwin’s theory. (Thomson’s objections were based

on his understanding of Earth’s cooling. He calcu-

lated that it would have ‘died’ were it as old as geo-

logical theory indicated. Radioactivity had not then

been discovered, and so he had no mechanism by

which Earth could be both very old and warm.)

Wilberforce’s objections (which successfully drew at-

tentiontoweaknessesinDarwin’s original theory) were

not long shared by the theological faculties of the uni-

versities of England and Scotland. On the contrary, by

the early 1880s, Darwin’stheorywasbeingembraced

as evidence of the immense providence of God. Fred-

erick Temple’s Bampton Lectures of 1884 and the Lux

Mundi collection of essays edited by Charles Gore in

1889 embraced the new scientific developments.

BIBLICAL GEOLOGY 257

Through the twentieth century, there has been a

perceived opposition between science and Christian-

ity, in particular, driven by those who adhere to

Ussher’s dating of the creation of the heavens and

Earth. Generally known as Creationists, opponents

of the ‘new’ geology and biology have portrayed Dar-

winian evolutionary theories as anti-Christian. But,

interestingly, they have tried to conscript science to

the Creationist cause. So-called Creation science (see

Creationism) has tried to adapt scientific learning to

prove that Earth is very young (only several thousand

years old). In no way does Creation science satisfy the

methodological rubrics of the scientific community,

and Creationist interpretations of the data are univer-

sally rejected. It is interesting that Creation scientists

want to appeal to science to establish their case.

Even for religious literalists, it would appear that

the best way to describe the physical universe is

what is generally understood as scientifically. But

this is understandable in that they operate chiefly in

the ‘scientistic’ culture of the United States.

In the United States in the late twentieth century,

objections to Creation science being taught in school

science curricula have been led by mainstream Chris-

tians and Jews. (The plaintiffs in the 1981 action to set

aside as unconstitutional Act 590 of the Arkansas Legis-

lature, ‘‘Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and

Evolution-Science Act’’, included the resident Arkansas

bishops of the United Methodist, Episcopal, Roman

Catholic, and African Methodist Episcopal Churches,

the Principal Officer of the Presbyterian churches in

Arkansas, and other United Methodist, Southern Bap-

tist, and Presbyterian clergy. Organisational plaintiffs

included the American Jewish Congress, the Union of

American Hebrew Congregations, and the American

Jewish Committee.) For most Christians and Jews

there is no perceived clash between their religious faith

and the scientific enterprise.

The Bible is a collection of religious texts gathered

and edited over a period in excess of a 1000 years,

concluding in the early decades of the second century

CE (anno domini). The texts are products of the times

and places in which people have struggled to under-

stand the ultimate significance and meaning of life.

They reflect religious conviction and searching and

have never been scientific texts, in the way that sci-

entific texts have been understood since the late

Middle Ages when modern science began to develop.

However, events that may have appeared miraculous

to the authors of the Old Testament can be understood

satisfactorily in terms of modern geological know-

ledge. Religious knowledge and scientific knowledge

deal with the same world and universe, but they oper-

ate with fundamentally different presuppositions of

causality. This means that they can overlap and inter-

act, but the causalities for science are proximate and

immediate, and, for religion, are ultimate and perhaps

eternal.

See Also

Creationism. Famous Geologists: Cuvier; Darwin;

Hutton; Lyell. Geomythology. Tectonics: Earth-

quakes. Volcanoes.

Further Reading

Alter R (1996) Genesis. New York: WW Norton.

Go

¨

ru

¨

r N, Cagatay MN, Emre O, et al. (2001) Is the abrupt

drowning of the Black Sea shelf at 7150 yr BP a myth?

Marine Geology 176: 65–73.

Lewis CLE and Knell SJ (eds.) (2001) The Age of the Earth:

From 4004 BC to AD 2002. London: The Geological

Society.

Numbers RL (1992) The Creationists. New York and

Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf .

Plimer I (2001) A Short History of Planet Earth. Sydney:

ABC Books.

Ruse M (1999) Mystery of Mysteries. Cambridge: Harvard

University Press.

Ryan W and Pitman W (2000) Noah’s Flood. New York:

Touchstone.

Wilson I (2001) Before the Flood. London: Orion Books.

258 BIBLICAL GEOLOGY

a0005 BIODIVERSITY

A W Owen, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

ß 2005, Elsevier Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

In its broadest sense, biodiversity encompasses all

hereditarily based variation at all levels of organiza-

tion from genes through populations and species to

communities and ecosystems. The term is a modern

one, stemming from the early 1980s, and is a contrac-

tion of ‘biological diversity’, which has a long pedi-

gree as an area of scientific investigation. Concerns

over the rate of extinction of modern species have

brought the study of biodiversity (and indeed the

word itself) to the forefront of scientific, political,

and popular concern. The fossil record both estab-

lishes the ecological and palaeobiogeographical ori-

gins of present-day biodiversity and provides an

understanding of the longer-term influences on bio-

diversity of changes in climate, eustasy, and many

other processes operating at the Earth’s surface.

Biodiversity is measured in several ways, and there

are considerable uncertainties in determining the

number of living species, let alone the assessment of

diversity through geological time. Databases com-

piled at a variety of geographical, taxonomic, and

temporal scales have become powerful tools for as-

sessing Phanerozoic biodiversity change, but there are

significant concerns about the biases that might be

inherent in the fossil data. The patterns emerging for

the marine and terrestrial realms are very different,

and there is a lively debate about how the global

curves should be interpreted. Nonetheless, they have

an important role to play in understanding the pat-

terns and processes of biodiversity change in the

modern world and therefore in the development of

appropriate conservation strategies.

The Measurement of Biodiversity

Types of Biodiversity

Biodiversity is variously defined in terms of genes,

species (or higher taxa), or ecosystems. The genetic

and organism components have been combined by

many authors and, in many palaeontological studies,

a clear distinction is now commonly made between

taxonomic diversity and disparity – the degree of mo-

rphological variability exhibited by a group of taxa.

Disparity can be measured either by phylogenetic

distance or by various phenetic indices. Within the

history of a major clade, disparity may reach a peak

before the peak in species richness is attained.

Setting aside disparity, two basic categories of bio-

diversity measurement have become widely used:

inventory diversity, which records the number of

taxa per unit area, and differentiation diversity,

which provides a measure of the difference (or simi-

larity) between levels of inventory diversity. Alpha (or

within-habitat) diversity is the most common form of

inventory diversity and records the number of taxa

per area of homogenous habitat, thus reflecting

species packing within a community. At its simplest,

alpha diversity is species richness (i.e. the number of

species in one area), but, especially in the study of

modern diversity, its measurement also includes some

assessment of abundance. Beta diversity, a differenti-

ation metric, measures the variation in taxonomic

composition between areas of alpha diversity. For

larger areas, in many studies of terrestrial environ-

ments, the term gamma diversity has been used to

reflect the number of taxa on an island or in a dis-

tinctive landscape, and epsilon diversity has been

used for the inventory diversity of a large biogeo-

graphical region; the term delta diversity is occasion-

ally used for the variation between areas of gamma

diversity within such a region. However, in palae-

ontological analyses of marine faunas, many workers

have used the term gamma diversity for differenti-

ation diversity measuring taxonomic differentiation

between geographical regions and therefore reflecting

provinciality or the degree of endemicity.

Assessment of the numbers of higher taxa has

been an important facet of the analysis of biodiversity

– one point sample or community may contain

more species than another while having fewer higher

taxa and possibly, therefore, a lower genetic diversity

and morphological disparity. Moreover, higher taxa

are widely used as surrogates for species in bio-

diversity analyses, especially but not exclusively in

the fossil record, where this approach reduces the

effects of preservational biases, uncertainties in

species identification, and the worst excesses of

over-divisive species-level taxonomy. It also facilitates

the analysis of biodiversity in biotas within which

species-level identifications have not been under-

taken because of lack of time or expertise. However,

there is a need for caution: the correlation between

number of species and number of higher taxa is at

best a crude one and diminishes with increasing taxo-

nomic rank. As a result, there is an increasing discord-

ance between the diversity curves calculated from

BIODIVERSITY 259

progressively higher taxa and those calculated from

species.

Modern Biodiversity

About 1.8 million modern species have been formally

described, but there are enormous gaps in our know-

ledge of the true number of living species, and the

data are patchy in terms of both taxonomic group and

geographical coverage. Estimates of modern biodiver-

sity vary considerably depending on the methods used

and range from 3.5 to 111.5 million species, with

about 13.5 million being considered a reasonable

working figure. Less than 15% of the described living

species are marine, but over 90% of all classes and

virtually all phyla are represented in that environ-

ment, with two-thirds of all phyla known only from

there. However, conservative estimates of the actual

numbers of species of plants and animals (excluding

micro-organisms) suggest that marine species may

comprise as little as 4.1% of the total.

There is a crude inverse relationship between body

size and species diversity, and the problems of quan-

tifying prokaryotic diversity are the most acute. The

development of molecular methods over the last few

decades has revealed levels of species diversity that

are orders of magnitude greater than those recorded

previously using culture techniques and has more

than trebled the number of major prokaryote div-

isions now recognized. Though still fraught with un-

certainties, not least the definition of what constitutes

a species, the estimation of prokaryote diversities

from species-abundance curves holds considerable

potential; recent calculations suggest that the oceans

may have a total bacterial diversity of less than

2 10

6

species, whereas a ton of soil could contain

twice this figure.

Ancient Biodiversity

The quantification of ancient biodiversity has a long

history, with the 1860 compilation by John Phillips

of the changing number of marine species through

geological time being widely regarded as including

the first published biodiversity curve. This was based

on fossil faunas from the British Isles and was cali-

brated to take account of the total thickness of each

stratigraphical interval. Its overall shape is remark-

ably similar to many of the biodiversity curves

published over the last four decades based on global

datasets. Since the 1960s, there has been a lively

debate surrounding the compilation and interpret-

ation of data at a range of taxonomic levels to show

the changing patterns of biodiversity through geo-

logical time. This scientific endeavour has been

greatly facilitated by the development of increasingly

sophisticated large computer databases. These vary

greatly in both the scope and refinement of their

geographical, temporal, and taxonomic coverage

and in the origins of the data included in them. The

data range from first-hand sample data through as-

sessments of the primary literature to secondary com-

pilations. Similarly there is considerable variation in

the metrics used to plot and analyse the data.

Global marine diversity curves for the Phanerozoic

compiled at the family level from different databases

have proved to be remarkably similar. Moreover, the

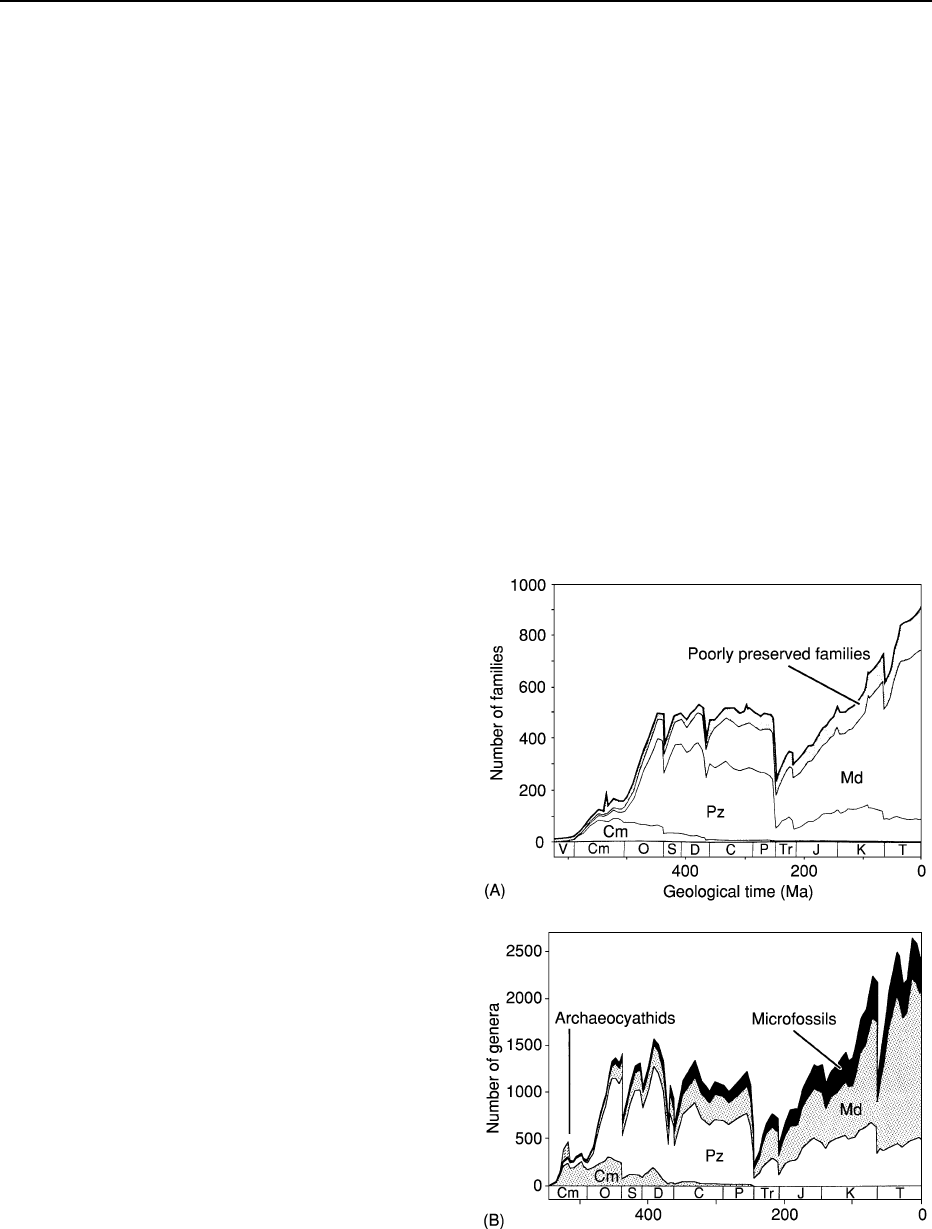

most widely cited family- and genus-level curves, de-

veloped by JJ Sepkoski (e.g., Figure 1), have proved

to be robust when recalculated to take account of

substantial revisions of the underlying database in

terms of the taxonomy and stratigraphy of many of

the entries. This reflects the random distribution

of such errors and inaccuracies and is a common

phenomenon when analysing large palaeontological

databases. There has been some debate over the like-

lihood of an artificial steepening of the Cenozoic

Figure 1 (A) Family-level and (B) genus-level marine diversity

curves, showing the changing proportions of the Cambrian (Cm),

Palaeozoic (Pz), and Modern (Md) evolutionary faunas through

the Phanerozoic. (Adapted from Sepkoski JJ (1997) Biodiversity:

past, present, and future.

Journal of Paleontology 71: 533–539.)

260 BIODIVERSITY

parts of the diversity curves by the ‘pull of the recent’

– the possibility that the relatively well-sampled living

fauna may extend the stratigraphical ranges of those

taxa that also occur in the fossil record, whereas more

ancient fossil taxa without modern representatives

are less likely to have such complete range records.

However, detailed analysis of those modern bivalve

genera that have a fossil record has revealed that 95%

occur in the Pliocene or Pleistocene, indicating that,

for this major group at least, the modern occurrences

have only a very small influence on the shape of the

Cenozoic diversity curve.

Setting aside the ‘pull of the recent’, there have been

increasing concerns that the global diversity curves

may be strongly influenced by taxonomic practice,

the temporal sampling pattern used, major geograph-

ical gaps in sampling, the absence of information on

abundance, and, perhaps most significantly, major

biases in the rock record from which the fossil data

are derived.

Biases in the marine rock record principally reflect

changes in sea-level and can be understood in terms

of sequence stratigraphy (see Sequence Stratigraphy).

They result both from variations in the total outcrop

area of rock available for study and from the periodic

restriction of the available record to particular environ-

ments. Thus, for example, in the post-Palaeozoic suc-

cession in western Europe, patterns of standing

diversity and (apparent) origination and extinction on

time-scales of tens of millions of years show a strong

correlation with surface outcrop area. Perhaps most

tellingly, the ‘mass extinction’ peaks are strongly cor-

related with second-order depositional cycles, coincid-

ing with either sequence bases or maximum flooding

surfaces. In the former case, the amount of fossiliferous

marine rock is very limited (and biased towards shal-

low-water facies), whereas, in the latter case, there is a

strong bias towards deep-water environments and

hence a taphonomic bias against shallower-water

faunas being available for sampling. In contrast, evi-

dence from fossil tetrapods indicates that, despite

earlier assumptions to the contrary, there is no correl-

ation between sea-level change and the quality of the

continental fossil record.

Biodiversity Change

Precambrian Biodiversity

From its appearance in the Archaean, life had a pro-

found effect on the chemistry of the oceans and at-

mosphere during much of Precambrian time, but the

overall pattern of diversity change during most of this

interval is still weakly constrained. Given the difficul-

ties of assessing diversity in living bacteria and the

importance of molecular techniques therein, any

understanding of their ancient diversity as repre-

sented by fossil material is severely limited. In add-

ition, there is still debate about links between

organism diversity and disparity of stromatolites and

even about the biotic origin of some such structures

(see Biosediments and Biofilms). The development of

eukaryotic cells in the Early Proterozoic marked a

major change in organism complexity, and the widely

distributed fossil record of protists suggests that their

diversity (probably, more strictly, disparity) remained

low until about 1000 Ma, the age of the Mesoproter-

ozoic–Neoproterozoic boundary, after which there

were major increases in diversity and turnover rates.

A trough in diversity during the interval of the Late

Neoproterozoic that was characterized by major gla-

cial events was immediately followed by another

peak. This was a short-lived event, which overlapped

only slightly with the flourishing of the enigmatic

soft-bodied Ediacara biota. The dip in protist diver-

sity during the latest Precambrian was followed by a

major diversification that was coincident with that of

marine invertebrates.

The Ediacara biota flourished for about 30 Ma and

represents the first unequivocal record of metazoans

in the body-fossil record. The oldest fossil representa-

tives of this soft-bodied biota are recorded from a

horizon in Newfoundland that is about 10–15 Ma

younger than diamictites of the last of the Neoproter-

ozoic glaciations, which have been dated at about

595 Ma, but the size (up to about 2 m) and complex-

ity of these organisms indicate an earlier history.

Whether this indicates an origin prior to the latest

glacial event or very rapid evolution thereafter re-

mains uncertain. Either way, the Late Neoprotero-

zoic glaciations (the so-called ‘Snowball Earth’)

probably had a profound effect on the early evolution

of metazoans.

A few weakly mineralized metazoans are known

from the latest Neoproterozoic, and a large fully

mineralized metazoan, Namapoikia, of probable

cnidarian or poriferan affinities has been described

from rocks dated at about 549 Ma. Molecular data

suggest that most benthic metazoan groups had a

Proterozoic history prior to their acquisition of min-

eralized skeletons and their appearance in the fossil

record during the Cambrian ‘explosion’. Some of this

earlier history may be indicated by trace fossils, but

many trace fossils below the uppermost Neoprotero-

zoic are controversial. Recent estimates using mo-

lecular data suggest that the metazoans originated at

some time between 1000 Ma and 700 Ma, but the

origins and early history of metazoan groups and

hence their diversity during the Proterozoic remain

unknown.

BIODIVERSITY 261