Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

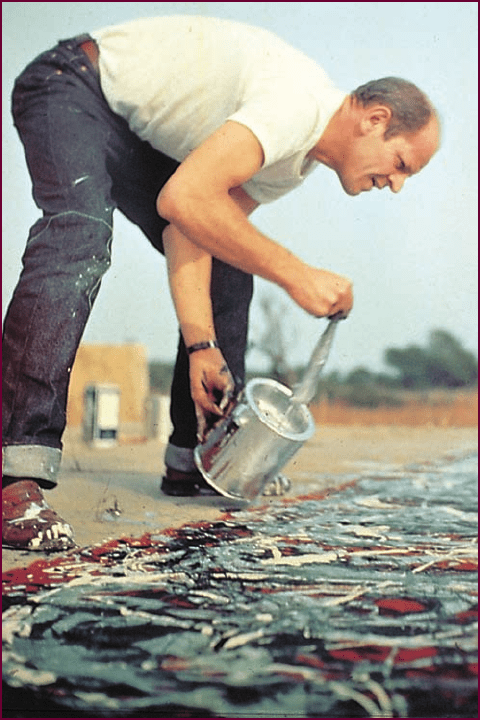

I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, since this way I

can walk around it, work from four sides and be literally

in the painting. When I am in the painting, I am not

aware of what I am doing. There is pure harmony.’’

Postmodernism’s eclectric commingling of past tra-

dition with Modernist innovation became increasingly

evident in architecture. Robert Venturi argued that ar-

chitects should look as much to the commercial strips of

Las Vegas as to the historical styles of the past for inspi-

ration. One example is provided by Charles Moore. His

Piazza d’Italia (1976--1980) in New Orleans is an outdoor

plaza that combines Classical Roman columns with

stainless steel and neon lights. This blending of modern-

day materials with historical references distinguished the

Postmodern architecture of the late 1970s and 1980s from

the Modernist glass box.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the ar t and music

industries increasingly adopted the techniques of mar-

keting and advertising. With large sums of money in-

vested in painters and musicians, pressure mounted to

achieve critical and commercial success. Negotiating the

distinction between art and popular culture was es-

sential since many equated merit w ith sales or economic

value.

In the art world, Neo-Expressionism reached its

zenith in the mid-1980s. Neo-Expressionist artists like

Anselm Kiefer became increasingly popular as the art

market soared. Born in Germany in 1945, Kiefer com-

bines aspects of Abstract Expressionism, collage, and

German Expressionism to create works that are stark and

haunting. His Departure from Egypt (1984) is a medita-

tion on Jewish history and its descent into the horrors of

Nazism. Kiefer hoped that a portrayal of Germany’s

atrocities could free Germans from their past and bring

some good out of evil.

The World of Science and Technology

Many of the scientific and technological achievements

since World War II have revolutionized people’s lives.

During World War II, university scientists were re-

cruited to work for their governments and develop new

weapons and practical instruments of war. British

physicists played a crucial role in the development of an

improved radar system that helped defeat the German

air force in the Battle of Britain in 1940. German sci-

entists created self-propelled rockets as well as jet air-

planes to keep Hitler’s hopes alive for a miraculous

turnaround in the war. The computer, too, was a war-

time creation. The British mathematician Alan Turing

designed a primitive computer to assist British intelli-

gence in breaking the secret codes of German ciphering

machines. The most famous product of wartime sci-

entific research was the atomic bomb, created by a team

of American and European scientists under the guid-

ance of the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. Although

most war time devices were created f or destructive

purposes, they could easily be adapted for peacetime

uses.

The postwar alliance of science and technology led to

an accelerated rate of change that became a fact of life in

Western society (see the comparative essay ‘‘From the

Industrial Age to the Technological Age’’ on p. 717). One

product of this alliance---the computer---may yet prove to

be the most revolutionary of all the technological in-

ventions of the twentieth century. Early computers, which

required thousands of vacuum tubes to function, were

large and hot and took up considerable space. The de-

velopment of the transistor and then the silicon chip

Jackson Pollock at Work. One of the best-known practitioners of

Abstract Expressionism, which remained at the center of the artistic

mainstream after World War II, was the American Jackson Pollock, who

achieved his ideal of total abstraction in his drip paintings. He is shown here

at work at his Long Island studio. Pollock found it easier to cover his large

canvases with exploding patterns of color when he put them on the floor.

c

Hans Namuth/Photo Researchers, Inc.

716 CHAPTER 28 EUROPE AND THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE SINCE 1945

produced a revolutionary new approach to computer

design. With the invention in 1971 of the microprocessor,

a machine that combines the equivalent of thousands of

transistors on a single, tiny silicon chip, the road was

open for the development of the personal computer. By

the 1990s, the personal computer had become a regular

fixture in businesses, schools, and homes. The Internet---

the world’s largest computer network---provides people

around the world with quick access to immense quanti-

ties of information, as well as rapid communication and

commercial transactions. As of 2010, estimates are that

more than a billion people worldwide are using the

Internet.

Despite the marvels produced by science and tech-

nology, some people have come to question their un-

derlying assumption---that scientific knowledge gives

human beings the ability to manipulate the environment

for their benefit. They maintain that some technological

advances have far-reaching side effects that are damaging

to the environment. Chemical fertilizers, for example,

once touted for producing larger crops, have wreaked

havoc with the ecological balance of streams, rivers, and

woodlands. Small Is Beautiful, written by the British

economist E. F. Schumacher (1911--1977), is a funda-

mental critique of the dangers of the new science and

technology (see the box on p. 718).

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

F

ROM THE INDUSTRIAL AGE TO THE TECHNOLOGICAL AGE

As many observers have noted, a key aspect of the

world economy is that it is in the process of transi-

tion to what has been called a ‘‘postindustrial age,’’

characterized by a system that is not only increas-

ingly global in scope but also increasingly technology-intensive in

character. Since World War II, a stunning array of technological

changes—especially in transportation, communications, space

exploration, medicine, and agricul-

ture—have transformed the world in

which we live. Technological changes

have also raised new questions and

concerns as well as producing some

unexpected results. Some scientists

have worried that genetic engineering

might accidentally result in new

strains of deadly bacteria that cannot

be controlled outside the laboratory.

Some doctors have recently warned

that the overuse of antibiotics has

created supergerms that are resistant

to antibiotic treatment. The Techno-

logical Revolution has also led to the

development of more advanced meth-

odsofdestruction.Mostfrightening

have been nuclear weapons.

The transition to a technology-intensive

postindustrial world, which the futurolo-

gist Alvin Toffler has dubbed the Third Wave (the first two being the

Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions), has produced difficulties for

people in many walks of life---for blue-collar workers, whose high

wages price them out of the market as firms begin to move their fac-

tories abroad; for the poor and uneducated, who lack the technical

skills to handle complex tasks in the contemporary economy; and

even for some members of the middle class, who have been fired or

forced into retirement as their employers seek to reduce payrolls or

outsource jobs to compete in the global marketplace.

It is now increasingly clear that the Technological Revolution,

like the Industrial Revolution that preceded it, wi ll entail enormous

consequences and may ultimately give birth to a new era of social

and political instability. The success of advanced capitalist states in

the post--World War II era has been built

on a broad consensus on the importance of

two propositions: (1) the need for high lev-

els of government investment in education,

communications, and transportation as a

means of meeting the challenges of contin-

ued economic growth and technological in-

novation and (2) the desirability of

cooperative efforts in the international

arena as a means of maintaining open mar-

kets for the free exchange of goods.

In the twenty-first century, these

assumptions are increasingly under attack

as citizens refuse to vote for the tax

increases required to support education and

oppose the formation of trading alliances to

promote the free movement of goods and

labor across national borders. The break-

down of the public consensus that brought

modern capitalism to a pinnacle of achieve-

ment raises serious questions about the like-

lihood that the coming challenges of the Third Wave can be

successfully met without a growing measure of political and social

tension.

Q

What is implied by the term Third Wave, and what challenges

does the Third Wave present to humanity?

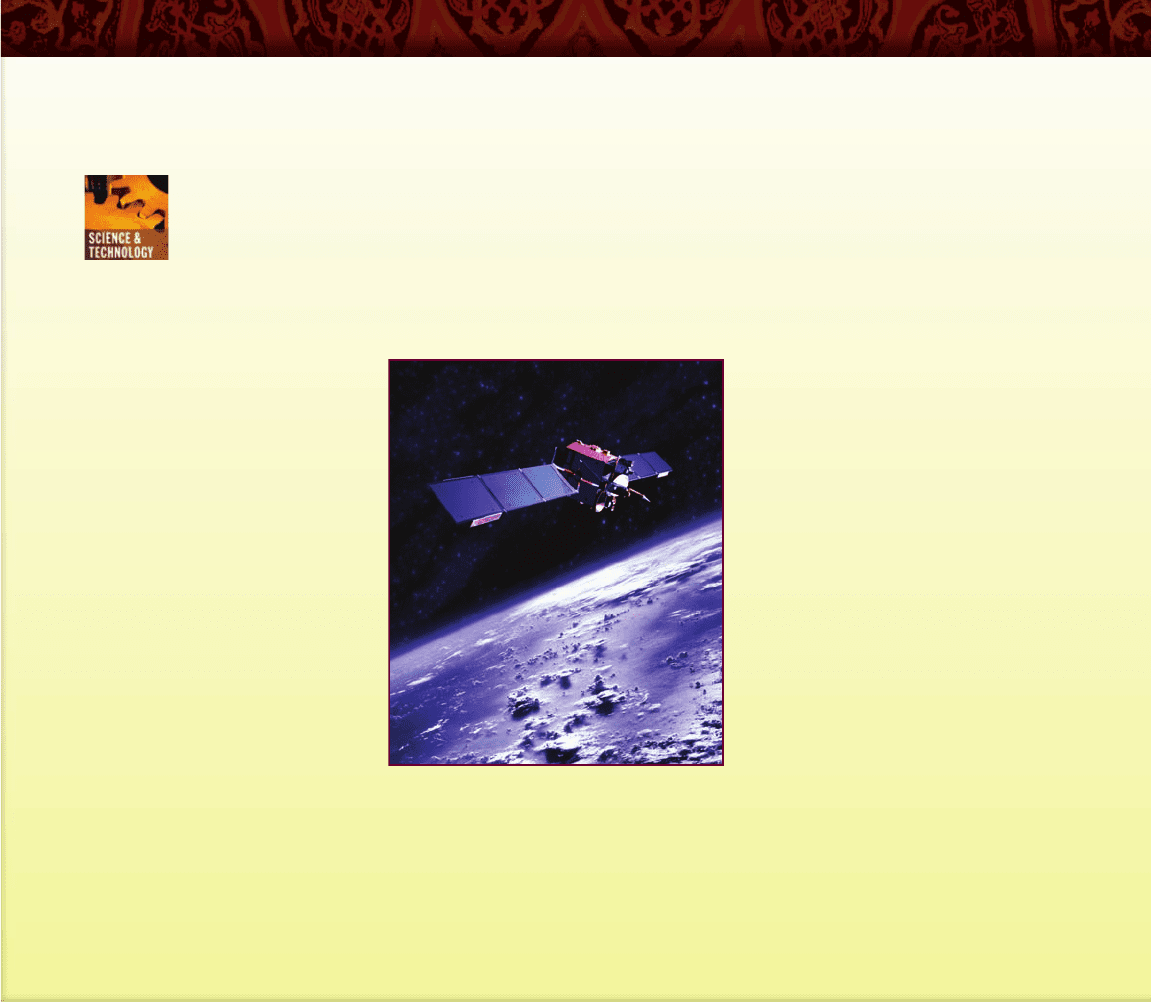

The Technological Age. A communication

satellite is seen orbiting above the earth.

c

Adastra/Getty Images

SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE WESTERN WORLD 717

The Explosion of Popular Culture

Popular culture since 1900, and especially since World

War II, has played an important role in helping Western

people define themselves. It also reflects the economic

system that supports it, for this system manufactures,

distributes, and sells the images that people consume as

popular culture. Modern popular culture is therefore

inextricably tied to the mass consumer society in which it

has emerged.

The United States has been the most influential force

in shaping popular culture in the West and, to a lesser

degree, the entire world. Through movies, music, adver-

tising, and television, the United States has spread its

particular form of consumerism and the American dream

to millions around the world. In 1923, the New York

Morning Post noted that ‘‘the film is to America what the

flag was once to Britain. By its means Uncle Sam may

hope some day ... to Americanize the world.’’

5

That day

has already come.

Motion pictures were the primary vehicle for the

diffusion of American popular culture in the years im-

mediately following World War I and continued to find

ever wider markets as the century rolled on. Television,

developed in the 1930s, did not become readily available

until the late 1940s, but by 1954, there were 32 million

sets in the United States as television became the cen-

terpiece of middle-class life. In the 1960s, as television

spread around the world, American networks unloaded

their products on Europe and the Third World at ex-

traordinarily low prices.

The United States has also dominated popular music

since the end of World War II. Jazz, blues, rhythm and

blues, rap, and rock and roll have been by far the most

popular music forms in the Western world---and much of

the non-Western world---during this time. All of them

originated in the United States, and all are rooted in

African American musical innovations. These forms later

spread to the rest of the world, inspiring local artists, who

then transformed the music in their own ways.

SMALL IS BEAUTIFUL:THE LIMITS OF MODERN TECHNOLOGY

Although science and technology have produced an

amazing array of achievements in the postwar

world, some voices have been raised in criticism of

their sometimes destructive aspects. In 1975, in

a book titled Small Is Beautiful, the British economist E. F.

Schumacher examined the effects modern industrial technology

has had on the earth’s resources.

E. F. Schumacher, Small Is Beautiful

Is it not evident that our current methods of production are already

eating into the very substance of industrial man? To many people

this is not at all ev ident. Now that we have solved the problem of

production, they say, have we ever had it so good? Are we not better

fed, better clothed, and better housed than ever before---and better

educated? Of course we are: most, but by no means all, of us: in the

rich countries. But this is not what I mean by ‘‘substance.’’ The sub-

stance of mankind cannot be measured by Gross National Product.

Perhaps it cannot be measured at all, except for certain symptoms

of loss. However, this is not the place to go into the statistics of

these symptoms, such as crime, drug addiction, vandalism, mental

breakdown, rebellion, and so for th. Statistics never prove anything.

I started by saying that one of the most fateful errors of our age

is the belief that the problem of production has been solved. This illu-

sion, I suggested, is mainly due to our inability to recognize that the

modern industrial system, with all its intellectual sophistication, con-

sumes the very basis on which it has been erected. To use the lan-

guage of the economist, it lives on irreplaceable capital which it

cheerfully treats as income. I specified three categories of such capital:

fossil fuels, the tolerance margins of nature, and the human substance.

Even if some readers should refuse to accept all three parts of my ar-

gument, I suggest that any one of them suffices to make my case.

And what is my case? Simply that our most important task is

to get off our present collision course. And who is there to tackle

such a task? I think every one of us. ... To talk about the future is

useful only if it leads to action now. And what can we do now,

while we are still in the position of ‘‘never having had it so good’’?

To say the least ...we must thoroughly understand the problem and

begin to see the possibility of evolving a new lifestyle, with new

methods of production and new patterns of consumption: a lifestyle

designed for permanence. To give only three preliminary examples:

in agriculture and horticulture, we can interest ourselves in the per-

fection of production methods which are biologically sound, build

up soil fertility, and produce health, beauty, and permanence. Pro-

ductivit y will then look after itself. In industry, we can interest our-

selves in the evolution of small-scale technology, relatively

nonviolent technology, ‘‘technology with a human face,’’ so that peo-

ple have a chance to enjoy themselves while they are working, in-

stead of working solely for their pay packet and hoping, usually

forlornly, for enjoyment solely during their leisure time.

Q

According to Schumacher, under what illusion are modern

humans living? What three irreplaceable things does he suggest

people are consuming without noticing? What is ‘‘technology

with a human face’’? How does the author suggest this might

transform modern life? Are Schumacher’s ideas Postmodern?

Why or why not?

718 CHAPTER 28 EUROPE AND THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE SINCE 1945

The introduction of the video music channel MTV in

the early 1980s radically changed the music scene by

making image as important as sound in the selling of

records. Artists like Michael Jackson and Madonna be-

came superstars by treating the music video as an art

form. Rather than merely a recorded performance, many

videos were short films with elaborate staging and special

effects set to music. The music of the 1980s was also af-

fected by technological advances, especially the advent of

the synthesizer, an electronic piano that produced com-

puterized sounds.

In the postwar years, sports have become a major

product of both popular culture and the leisure industry.

The development of satellite television and various elec-

tronic breakthroughs have helped make sports a global

phenomenon. Olympic Games can now be broadcast

around the globe from anywhere in the world. Sports

have become a cheap form of entertainment, as fans do

not have to leave their homes to enjoy athletic com-

petitions. As sports television revenues have escalated,

many sports now receive the bulk of their yearly revenue

from television contracts.

TIMELINE

1945 1955

1965 1975 1985 1995 2005 2010

Rule of Juan Perón

in Argentina

Martin Luther King Jr.

and the civil rights movement

Jackson Pollock,

Lavender Mist

Sexual revolution and drug culture Tony Blair

becomes British

prime minister

Terrorist attack on

the United States

Emergence of Green movement

Movement toward democracy

in Latin America

Emergence of women’s liberation movement

Student protests in France and the United States

De Gaulle’s rule in France Expansion of European

Economic Community

Reunification of Germany

Introduction of euro

Election of

Barack Obama

Expansion of the

European Union

CONCLUSION

WESTERN EUROPE BECAME a new community in the 1950s

and 1960s as a remarkable economic recovery fostered a new

optimism. Western European states became accustomed to political

democracy, and with the development of the European Community,

many of them began to move toward economic unity. But nagging

economic problems, new ethnic divisions, environmental degrada-

tion, and the inability to work together to stop a civil war in their

own backyard have all indicated that what had been seen as a

glorious new path for Europe in the 1950s and 1960s had become

laden with pitfalls in the 1990s and early 2000s.

In the Western Hemisphere, the two North American

countries---the United States and Canada---built prosperous econo-

mies and relatively stable communities in the 1950s, but there too,

new problems, including ethnic, racial, and linguistic differences as

well as persistent economic difficulties, dampened the optimism of

the earlier decade. Though some Latin American nations shared in

the economic growth of the 1950s and 1960s, it was not matched by

any real political stability. Only in the 1980s did democratic

governments begin to replace oppressive military regimes.

Western societies after 1945 were also participants in an era of

rapidly changing international relationships. While Latin American

countries struggled to find a new relationship with the colossus to

the north, European states reluctantly let go of their colonial

empires. Between 1947 and 1962, virtually every colony achieved

independence and statehood. Decolonization was a difficult and

even bitter process, but as we shall see in the next chapters, it

created a new world as the non-Western states ended the long

ascendancy of the Western nations.

CONCLUSION 719

SUGGESTED READING

Europe Since 1945 For a well-written survey on Europe since

1945, see T. Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 (New

York, 2005). See also W. I. Hitchcock, The Struggle for Europe: The

Turbulent History of a Divided Continent, 1945--2002 (New York,

2002). On the building of common institutions in Western Europe,

see S. Henig, The Uniting of Europe: From Discord to Concord

(London, 1997). For a survey of West Germany, see H. A. Turner,

Germany from Partition to Reunification (New Haven, Conn., 1992).

France under de Gaulle is examined in J. Jackson, Charles de Gaulle

(London, 2003). On Britain, see K. O. Morgan, The People’s Peace:

British History, 1945--1990 (Oxford, 1992). On the recent history of

these countries, see E. J. Evans, Thatcher and Thatcherism (New

York, 1997); M. Temple, Blair (London, 2006); D. S. Bell, Franc¸ois

Mitterrand (Cambridge, 2005); and P. O’Dochartaigh, Germany

Since 1945 (New York, 2004). On Eastern Europe, see P. K e n n e y, The

Burden of Freedom: Eastern Europe Since 1989 (London, 2006).

The United States and Canada For a general survey of U.S.

history since 1945, see W. H. Chafe, Unfinished Journey: America

Since World War II (Oxford, 2006). More detailed accounts can be

found in two volumes by J. T. Patterson in the Oxford History of

the United States series: Grand Expectations: The United States,

1945--1974 (Oxford, 1997) and Restless Giant: The United States

from Watergate to Bush v. Gore (Oxford, 2005). Information on

Canada can be found in S. W. See, History of Canada (Westport,

N.Y., 2001), and C. Brown, ed., The Illustrated History of Canada,

4th ed. (Toronto, 2003).

Latin America For general surveys of Latin American history,

see M. C. Eakin, The History of Latin America: Collision of Cultures

(New York, 2007), and E. Bradford Burns and J. A. Charlip, Latin

America: An Interpretive History, 8th ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J.,

2007). The twentieth century is the focus of T. E. Skidmore and

P. H. Smith, Modern Latin America, 6th ed. (Oxford, 2004). Works

on other countries examined in this chapter include L. A. P

erez,

Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution, 3rd ed. (New York, 2005);

J. A. Page, Per

on: A Biography (New York, 1983); L. A. Romero,

History of Argentina in the Twentieth Century, trans. J. P. Brennan

(University Park, Pa., 2002); and M. C. Meyer and W. L. Sherman,

The Course of Mexican History, 8th ed. (New York, 2006).

Society in the Wester n World On the sexual revolution of the

1960s, see D. Allyn, Make Love, Not War: The Sexual Revolution---An

Unfettered History (New York, 2000). On the women ’s liberation

movement, see C. Duchen, Women ’s Rights and Women’ s Lives in

France, 1944--1968 (New York, 1994); D. Meyer, The Rise of Women

in America, Russia, Sweden, and Italy, 2nd ed. (Middletown, Conn.,

1989); and K. C. Berkeley, The Women ’s Liberation Movement in

America (Westport, Conn., 1999). The changing role of women is

examined in R. Rosen, The World Split Open: How the Modern

Women’ s Movement Changed America (New York, 2001). On

terrorism, see W. La queur, History of Terrorism (New York, 2001),

and C. E. Simonsen and J. R. Spendlov e, Terrorism Today: The Past,

the Players, the Futur e, 3rd ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J., 2006). On

the development of Green Parties, see M. O’Neill, Green Parties and

Political Change in Contemporary Europe (Aldershot, England, 1997).

Western Culture Since 1945 For a general view of postwar

thought and culture, see J. A. Winders, European Culture Since

1848: From Modern to Postmodern and Beyond, rev. ed. (New

York, 2001). On existentialism, see T. Flynn, Existentialism: A Very

Short History, 5th ed. (Oxford, 2006). On Postmodernism, see

C. Butler, Postmodernism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford,

2002). On the arts, see A. Marwick, Arts in the West Since 1945

(Oxford, 2002).

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

720 CHAPTER 28 EUROPE AND THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE SINCE 1945

721

CHAPTER 29

CHALLENGES OF NATION BUILDING

IN AFRICA AND THE MIDDLE EAST

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

Uhuru: The Struggle for Independence in Africa

Q

What role did nationalist movements play in the

transition to independence in Africa, and how did such

movements differ from their counterparts elsewhere?

The Era of Independence

Q

How have dreams clashed with realities in the

independent nations of Africa, and how have African

governments sought to meet these challenges?

Continuity and Change in Modern African Societies

Q

How did the rise of independent states affect the lives

and the role of women in African societies? How does

that role compare with other par ts of the contemporary

world?

Crescent of Conflict

Q

What problems have the nations of the Middle East

faced since the end of World War II, and to what degree

have they managed to resolve those problems?

Society and Culture in the Contemporary

Middle East

Q

How have religious issues affected economic, social,

and cultural conditions in the Middle East in recent

decades?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

What factors can be advanced to explain the chronic

instability and internal conflict that have characterized

conditions in Africa and the Middle East since World

War II?

The African community, soul of a continent

c

William J. Duiker

722

AT THE END OF WORLD WAR II, many societies in Asia

and Africa had already been exposed to over half a century of colo-

nial rule. Althoug h Europeans complacently assumed that colonial-

ism was a necessar y evil in the process of introducing civilization to

backward peoples around the globe, many Asians and Africans dis-

agreed. Some even argued that the Western drive for political hege-

mony and economic profit, far from being a panacea for the world’s

ills, was a plague that threatened ultimately to destroy human

civilization.

One aspect of Western civilization that many observers in Asia

and Africa rejected was the concept of the nation-state as the natural

unit of communal identity in the modern world. In their view, na-

tionalism was at the root of many of the evils of the twentieth cen-

tury and should be rejected as a model for development in the

postwar period. In Africa, some intellectuals pointed to the tradi-

tional village community as a unique symbol of the humanistic and

spiritual qualities of the African people and promoted the concept

of ‘‘blackness’’ (n

egritude) as a common bond that could knit all the

peoples of the continent into a cohesive community. A similar rejec-

tion of the nation-state was prevalent in the Middle East, where

many Muslims viewed Western materialist culture as a threat to the

fundamental principles of Islam. To fend off the new threat from an

Uhuru: The Struggle for

Independence in Africa

Q

Focus Question: What role did nationalist movements

play in the transition to independence in Africa, and

how did such movements differ from their

counterparts elsewhere?

In the three decades following the end of World War II,

the peoples of Africa were gradually liberated from the

formal trappings of European colonialism.

The Colonial Legacy

As in Asia, colonial rule had a mixed impact on the so-

cieties and peoples of Africa (see Chapter 21). The Western

presence brought a number of short-term and long-term

benefits to Africa, such as improved transportation and

communication facilities, and in a few areas laid the

foundation for a modern industrial and commercial sec-

tor. Improved sanitation and medical care increased life

expectancy. The introduction of selective elements of

Western political systems after World War II laid the basis

for the gradual creation of democratic societies.

Yet the benefits of Westernization were distributed

very unequally, and the vast majority of Africans found

their lives little improved, if at all. Only South Africa and

French-held Algeria, for example, developed modern in-

dustrial sectors, extensive railroad networks, and modern

communications systems. In both countries, European

settlers were numerous, most investment capital for in-

dustrial ventures was European, and whites constituted

almost the entire professional and managerial class.

Members of the native population were generally re-

stricted to unskilled or semiskilled jobs at wages less than

one-fifth those enjoyed by Europeans.

Man y colonies concentrated on export crops---peanuts

in Senegal and Gambia, cotton in Egypt and Uganda,

coffee in Kenya, and palm oil and cocoa products in the

Gold Coast. Here the benefits of development were

somewhat more widespread. In some cases, the crops

were grown on plantations, which were usually owned by

Europeans. But plantation agriculture was not always

suitable in Africa (sometimes the cultivation of cash crops

eroded the fragile soil base and turned farmland into

desert), and much farming was done by free or tenant

farmers. In some areas, where landownership was tradi-

tionally vested in the community, the land was owned

and leased by the corporate village. The vast majority of

the profits from the exports, however, accrued to Euro-

peans or to merchants from other foreign countries, such

as India and the Arab emirates. The vast majority of

Africans continued to be subsistence farmers growing

food for their own consumption.

The Rise of Nationalism

Political organizations for African rights did not arise

until after World War I, and then only in a few areas, such

as British-ruled Kenya and the Gold Coast. After World

War II, following the example of independence move-

ments elsewhere, groups organized political parties with

independence as their objective. In the Gold Coast,

Kwame Nkrumah (1909--1972) led the Convention Peo-

ple’s Party, the first formal political party in black Africa.

In the late 1940s, Jomo Kenyatta (1894--1978) founded

the Kenya African National Union (KANU), which fo-

cused on economic issues but had an implied political

agenda as well.

For the most part, these political activities were

basically nonviolent and were led by Western-educated

African intellectuals. Their constituents were primarily

urban professionals, merchants, and members of labor

unions. But the demand for independence was not

entirely restricted to the cities. In Kenya, f or example,

the widely publicized Mau Mau movement among the

Kikuyu people used terrorism as an essential element of

its program to achieve uhuru (Swahili for ‘‘freedom’’)

from the British. Although most of the violence was

directed against other Africans, the specter of Mau Mau

terrorism alarmed the European population and con-

vinced the British government in 1959 to promise

eventual independence.

In areas such as South Africa and Algeria, where the

politi cal system was dominated by European settlers,

the transition to independence was more complicated.

UHURU: THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE IN AFRICA 723

old adversary, some dreamed of resurrecting the concept of a global

caliphate (see Chapter 7) to unify all Muslim peoples in realizing

their common destiny throughout the Islamic world.

Time has not been kind to such dreams of transnational soli-

darity and cooperation in the postwar world. Although the peoples

of Africa and the Middle East were gradually liberated from the for-

mal trappings of European authority, the legacy of colonialism in

the form of political inexperience and continued European economic

domination has frustrated the efforts of the leaders of the emerging

new states to achieve political stability. At the same time, arbitrary

boundaries imposed by the colonial powers, combined with ethnic

and religious divisions, have led to bitter conflicts that have posed a

severe obstacle to the dream of solidarity and cooperation in forging

a common destiny. Today, these two regions, although blessed with

enormous potential, are among the most volatile and conflict-ridden

areas in the world.

In South Africa, political activit y

by local Africans began w i th the

formation of the African National

Congress (ANC) in 1912. Ini-

tially, the ANC was dominated

by Western-oriented intellectuals

and had little mass support. Its

goal was to achieve economic and

political reforms, including full

equality for educated Africans,

within the framework of the ex-

isting system. But the ANC’s

efforts met with little success,

while conservative white parties

managed to stiffen the segregation

laws. In response, the ANC became

increasingly radicalized, and by the

1950s, the prospects for a violent

confrontation were growing.

In Algeria, resistance to

French rule by Berbers and Arabs

in rural areas had never ceased.

After World War II, urban agita-

tion intensified, leading to a

widespread rebellion against colo-

nial rule in the mid-1950s. At first,

the French government tried to

maintain its authority in Algeria.

But when Charles de Gaulle be-

came president in 1958, he re-

versed French policy, and Algeria

became independent under Presi-

dent Ahmad Ben Bella (1918--

2004) in 1962. The armed struggle

in Algeria hastened the transition

to statehood in its neighbors as

well. Tunisia won its independence

in 1956 after some urban agitation and rural unrest but

retained close ties with Paris. The French attempted to

suppress the nationalist movement in Morocco by send-

ing Sultan Muhammad V into exile, but the effort failed;

in 1956, he returned as the ruler of the independent state

of Morocco.

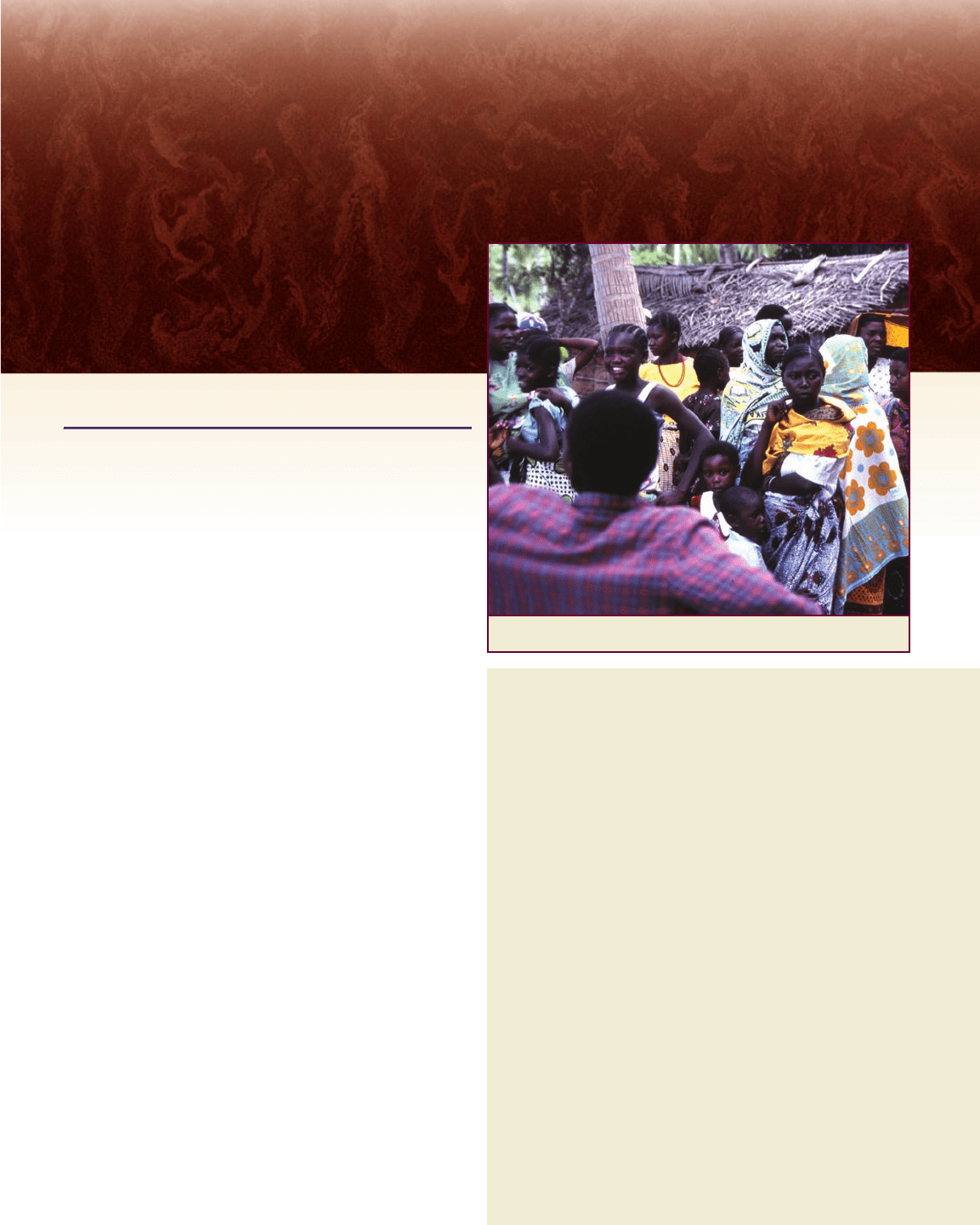

Most black African nations achieved their indepen-

dence in the late 1950s and 1960s, beginning with the

Gold Coast, now renamed Ghana, in 1957 (see

Map 29.1). Nigeria, the Belgian Congo (renamed Zaire

and then the Democratic Republic of the Congo), Kenya,

Tanganyika (later, when joined with Zanzibar, renamed

Tanzania), and several other countries soon followed.

Most of the French colonies agreed to accept indepen-

dence within the framework of de Gaulle’s French

Community. By the late 1960s, only parts of southern

Africa and the Portuguese possessions of Mozambique

and Angola remained under European rule.

Independence thus came later to Africa than to most

of Asia. Several factors help explain the delay. For one

thing, colonialism was established in Africa somewhat later

than in most areas of Asia, and the inevitable reaction

from the local population was consequently delayed. Fur-

thermore, with the exception of a few areas in West Africa

and along the Mediterranean, coherent states with a strong

sense of cultural, ethnic, and linguistic unity did not exist

in most of Africa. M ost traditional states, such as Ashanti

in West Africa, Songhai in the southern Sahara, and

Bakongo in the Congo basin, were collections of hetero-

geneous peoples with little sense of national or cultural

identity. It is hardly surprising that when opposition to

colonial rule emerged, unity was difficult to achieve.

BENIN

LIBERIA

GUINEA-

BISSAU

SIERRA

LEONE

MAURITANIA

ALGERIA

MOROCCO

WESTERN

SAHARA

(Morocco)

TUNISIA

CAMEROON

CENTRAL

AFRICAN

REPUBLIC

EQUATORIAL

GUINEA

GABON

CONGO

REP.

DEMOCRATIC

REPUBLIC OF

THE CONGO

KENYA

UGANDA

TANZANIA

RWANDA

BURUNDI

ANGOLA

NAMIBIA

ZAMBIA

ZIMBABWE

BOTSWANA

MADAGASCAR

SWAZILAND

LESOTHO

MOZAMBIQUE

REPUBLIC OF

SOUTH AFRICA

MALAWI

COMOROS

Zanzibar

Cabinda

Walvis

Bay

TOGO

BURKINA

FASO

GHANA

IVORY

COAST

NIGERIA

NIGER

MALI

EGYPT

SUDAN

CHAD

ETHIOPIA

DJIBOUTI

SOMALIA

SENEGAL

GAMBIA

GUINEA

ERITREA

C

o

n

g

o

R

.

LIBYA

Atlantic

Ocean

M

e

d

i

t

e

r

r

a

n

e

a

n

S

e

a

N

i

l

e

R.

N

i

g

e

r

R.

0 750 1,500 Miles

0 750 1,500 2,250 Kilometers

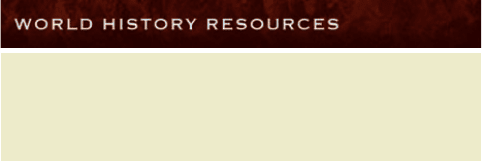

MAP 29.1 Modern Africa. This map shows the division of independent states in

Africa today.

Q

WhywasunitysodifficulttoachieveinAfricanregions?

724 CHAPTER 29 CHALLENGES OF NATION BUILDING IN AFRICA AND THE MIDDLE EAST

The Era of Independence

Q

Focus Question: How have dreams clashed with

realities in the independent nations of Africa, and how

have African governments sought to meet these

challenges?

The newly independent African states faced intimidating

challenges. Although Western political institutions, values,

and technology had been introduced, at least in the cities,

the exposure to European civilization had been superficial

at best for most Africans and tragic for many. At the

outset of independence, most African societies were still

primarily agrarian and traditional, and their modern

sectors depended mainly on imports from the West.

Pan-Africanism and Nationalism:

The Destiny of Africa

Like the leaders of new states in South and Southeast

Asia, most African leaders came from the urban middle

class. They had studied in either Europe or the United

States and spoke and read European languages. Although

most were profoundly critical of colonial policies, they

appeared to accept the relevance of the Western model to

Africa and gave at least lip service to Western democratic

values.

Their views on economics were somewhat more di-

verse. Some, like Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya and General

Mobutu Sese Seko (1930--1997) of Zaire, were advocates

of Western-style capitalism. Others, like Julius Nyerere

(1922--1999) of Tanzania, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana,

and S

ekou Tour

e (1922--1984) of Guinea, preferred an

‘‘African form of socialism,’’ which bore slight resem-

blance to the Marxist-Leninist socialism practiced in the

Soviet Union. According to its advocates, it was de-

scended from traditional communal practices in preco-

lonial Africa.

At first, most of the new African leaders accepted the

national boundaries established during the colonial era.

But as we have seen, these boundaries were artificial

creations of the colonial powers. Virtually all of the new

states included w idely diverse ethnic, linguistic, and ter-

ritorial groups. Zaire, for example, was composed of more

than two hundred territorial groups speaking seventy-five

different languages. Such conditions posed a severe chal-

lenge to the task of forming cohesive nation-states.

A number of leaders---including Nkrumah of Ghana,

Tou r

e of Guinea, and Kenyatta of Kenya---were enticed by

the dream of pan-Africanism, a concept of continental

unity that transcended national boundaries. Nkrumah in

particular hoped a pan-African union could be established

that would unite all of the new countries of the continent

in a broader community. His dream achieved concrete

manifestation in the Organization of African Unity

(O AU), which was founded in 1963 (see the box on p. 726).

Pan-Africanism originated among French-educated

African intellectuals during the first half of the twentieth

century. A basic element was the concept of n

egritude

(blackness), which held that there was a distinctive

‘‘African personality’’ that owed nothing to Western ma-

terialism and provided a common sense of destiny for

all black African peoples. Whereas Western civilization

prized rational thought and material achievement,

African culture emphasized emotional expression and a

common sense of humanity.

Dream and Reality: Political and Economic

Conditions in Independent Africa

The program of the OAU called for an Africa based on

freedom, equality, justice, and dignity and on the unity,

solidarity, prosperity, and territorial integrity of African

states. It did not take long for reality to set in. Vast dis-

parities in education and wealth made it hard to establish

material prosperity in much of Africa. Expectations that

independence would lead to stable political structures

based on ‘‘one person, one vote’’ were soon disappointed

as the initial phase of pluralistic governments gave way to

a series of military regimes and one-party states. Between

1957 and 1982, more than seventy leaders of African

countries were overthrown by violence, and the pace has

not abated in recent years.

The Problem of Neocoloniali sm Part of the problem

could be (and was) ascribed to the lingering effects of

colonialism. Most new countries in Africa were depen-

dent on the export of a single crop or natural resource.

When prices fluctuated or dropped, these countries were

at the mercy of the vagaries of the international market.

In several cases, the resources were still controlled by

foreigners, leading to the charge that colonialism had

been succeeded by neocolonialism, in which Western

domination was maintained by economic rather than by

political or military means.

World trade policies often exacerbated these prob-

lems. While advanced countries took aggressive action to

reduce tariff barriers on the worldwide flow of industrial

goods, at the same time they provided massive subsidies

to protect domestic producers of agricultural goods, thus

preventing poor countries in Africa and Asia from im-

proving their economic conditions through agricultural

exports. To make matters worse, most African states had

to import technology and manufactured goods from the

THE ERA OF INDEPENDENCE 725