Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

and economic prosperity. One is reminded of Chiang Kai-

shek’s failed attempt during the 1930s to revive Confucian

ethics as a standard of behavior for modern China: dead

ideologies cannot be revived by decree.

New leaders installed in 2002 and 2003 have indi-

cated that they are aware of the magnitude of the prob-

lem. Hu Jintao (b. 1942), who replaced Jiang Zemin as

CCP general secretary and head of state, has called for

further reforms to open up Chinese society and bridge

the yawning gap between rich and poor. In recent years,

the government has shown a growing tolerance for the

public exchange of ideas, which has surfaced with the

proliferation of bookstores, avant-garde theater, experi-

mental art exhibits, and the Internet. In 2005, an esti-

mated 27 percent of all Chinese citizens possessed a cell

phone. Today, despite the government’s efforts to restrict

access to certain websites, more people are ‘‘surfing the

Net’’ in China than in any other country except the

United States. The Internet is wildly popular with those

under thirty, who use it for online games, downloading

videos and music, and instant messaging. The challenges,

however, continue to be daunting. At the CCP’s Seven-

teenth National Congress, held in October 2007, President

Hu emphasized the importance of adopting a ‘‘scientific

view of development,’’ a vague concept calling for social

harmony, improved material prosperity, and a reduction

in the growing income gap between rich and poor in

Chinese society. But he insisted that the Communist Party

must remain the sole political force in charge of carrying

out the revolution. Ever fearful of chaos, party leaders are

convinced that only a firm hand at the tiller can keep the

ship of state from crashing onto the rocks.

In the fall of 2008, an economic crisis struck the fi-

nancial sector in the United States and then spread rap-

idly around the globe. Although China’s rapid economic

growth over the last two decades had shielded it from

previous economic downturns, this recession threatened

to have a more lasting impact as global demand for

Chinese goods dropped significantly. By the end of 2008,

massive layoffs in Chinese factories specializing in the

export trade raised the specter of rising social unrest and

presented a new challenge to the CCP’s leadership.

‘‘Serve the People’’: Chinese

Society Under Communism

Q

Focus Questions: What significant political, economic,

and soc ial changes have taken place in China since the

death of Mao Zedong? Have they been successful?

When the Communist Party came to power in 1949,

Chinese leaders made it clear that their policies would

differ from the Soviet model in one key respect. Whereas

the Bolsheviks had distrusted nonrevolutionary elements

in Russia and relied almost exclusively on the use of force

to achieve their objectives, the CCP sought to win support

from the mass of the population by carrying out reforms

that could win popular support. This ‘‘mass line’’ policy, as

it was called, worked fairly well until the late 1950s, when

Mao and his radical allies adopted policies such as the

Great Leap Forward that began to alienate much of the

population. Ideological purity was valued over expertise in

building an advanced and prosperous society.

Economics in Command

When he came to power in the late 1970s, Deng Xiaoping

recognized the need to restore credibility to a system on

the verge of breakdown and hoped that rapid economic

growth would satisfy the Chinese people and prevent

them from demanding political reforms. The post-Mao

leaders clearly emphasized economic performance over

ideological purity. To stimulate the stagnant industrial

sector, which had been under state control since the end

of the New Democracy era, they reduced bureaucratic

controls over state industries and allowed local managers

to have more say over prices, salaries, and quality control.

Productivity was encouraged by permitting bonuses for

extra effort, a policy that had been discouraged during

the Cultural Revolution. The regime also tolerated the

emergence of a small private sector. Unemployed youths

were encouraged to set up restaurants, bicycle or radio

repair shops, and handicraft shops on their own initiative

(see the comparative illustration on p. 679).

Finally, the regime opened up the country to foreign

investment and technology. Special economic zones were

established in urban centers near the coast (ironically,

many were located in the old nineteenth-century treaty

ports), where lucrative concessions were offered to en-

courage foreign firms to build factories. The tourist in-

dustry was encouraged, and students were sent abroad to

study.

The new leaders especially stressed educational re-

form. The system adopted during the Cultural Revolu-

tion, emphasizing practical education and ideology at the

expense of higher education and modern science, was

rapidly abandoned (the Little Red Book was even with-

drawn from circulation and could no longer be found on

bookshelves), and a new system based generally on the

Western model was instituted. Admission to higher ed-

ucation was based on success in merit examinations, and

courses in science and mathematics received high priority.

Agricultural Reform No economic reform program

could succeed unless it included the countryside. Three

686 CHAPTER 27 BRAVE NEW WORLD: COMMUNISM ON TRIAL

decades of socialism had done little to increase food

production or to lay the basis for a modern agricultural

sector. China, with a population numbering one billion,

could still barely feed itself. Peasants had little incentive

to work and few opportunities to increase production

through mechanization, the use of fertilizer, or better

irrigation.

Under Deng Xiaoping, agricultural policy made a

rapid about-face. Under the new rural responsibility

system, adopted shortly after Deng had consolidated his

authority, collectives leased land to peasant families, who

paid a quota in the form of rent to the collective. Any-

thing produced on the land above that payment could be

sold on the private market or consumed. To soak up

excess labor in the villages, the government encouraged

the formation of so-called sideline industries, a modern

equivalent of the traditional cottage industries in pre-

modern China. Peasants raised fish or shrimp, made

consumer goods, and even assembled living room furni-

ture and appliances for sale to their newly affluent

compatriots.

The reform program had a striking effect on rural

production. Grain production increased rapidly, and farm

income doubled during the 1980s. Yet it also created

problems. In the first place, income at the village level

became more unequal as some enterprising farmers

(known locally as ‘‘ten-thousand-dollar households’’)

earned profits several times those realized by their less

fortunate or less industrious neighbors. When some

farmers discovered that they could earn more by growing

cash crops or other specialized commodities, they de-

voted less land to rice and other grain crops, thereby

threatening to reduce the supply of China’s most crucial

staple. Finally, the agricultural policy threatened to un-

dermine the government’s population control program,

which party leaders viewed as crucial to the success of the

Four Modernizations.

Since a misguided period in the mid-1950s when

Mao Zedong had argued that more labor would result in

higher productivity, China had been attempting to limit

its population growth. By 1970, the government had

launched a stringent family planning program---including

education, incentives, and penalties for noncompliance---

to persuade the Chinese people to limit themselves to one

child per family. The program has had some success, and

population growth was reduced drastically in the early

1980s. The rural responsibility system, however, under-

mined the program because it encouraged farm families

to pay the penalties for having additional children in the

belief that their labor would increase family income

and provide the parents w ith a form of social security for

their old age. Today, China’s population has surpassed

1.3 billion.

Evaluating the Four Modernizations Still, the overall

effects of the modernization program were impressive. The

standard of living impro ved for the majority of the popu-

lation. Whereas a decade earlier , the average Chinese had

struggled to earn enough to buy a bicycle, radio, watch, or

washing machine, by the late 1980s, many were beginning to

purchase videocassette recor ders, refrigerators, and color

television sets. Yet the rapid growth of the economy created

its own problems: inflationary pressures, greed, envy,

increased corruption, and---most dangerous of all for the

regime---rising expectations. Young people in particular r e-

sented restrictions on employment (many young people in

China are still required to accept the jobs that are offered to

them by the government or school officials) and oppor-

tunities to study abroad. Disillusionment ran high, especially

in the cities, where lavish living by officials and rising prices

for goods aroused widespr ead alienation and cynicism.

During the 1990s, growth rates in the industrial

sector continued to be high as domestic capital became

increasingly available to compete with the growing pres-

ence of foreign enterprises. The government finally rec-

ognized the need to close down inefficient state

enterprises, and by the end of the decade, the private

sector, with official encouragement, accounted for more

than 10 percent of the gross domestic product. A stock

market opened, and China’s prowess in the international

marketplace improved dramatically.

As a result of these developments, China now pos-

sesses a large and increasingly affluent middle class and a

burgeoning domestic market for consumer goods. More

than 80 percent of all urban Chinese now own a color

television set, a refrigerator, and a washing machine. One-

third own their homes, and nearly as many have an air

conditioner. For the more affluent, a private automobile

is increasingly a possibility. Like their counterparts else-

where in Asia, urban Chinese are increasingly brand-

name conscious, a characteristic that provides a consid-

erable challenge to local manufacturers.

CHRONOL OGY

China Under Communist Rule

New Democracy 1949--1955

Era of collectivization 1955--1958

Great Leap Forward 1958--1960

Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution 1966--1976

Death of Mao Zedong 1976

Era of Deng Xiaoping 1978--1997

Tiananmen Square incident 1989

Presidency of Jiang Zemin 1993--2002

Hu Jintao becomes president 2002

‘‘S

ERVE THE PEO PLE’’: CHI NESE SOCIETY UNDER COMMUNISM 687

But as Chinese leaders have

discovered, rapid economic change

never comes without cost. The

closing of state-run factories has

led to the dismissal of millions of

workers each year, and the private

sector, although growing at more

than 20 percent annually, has

struggled to absorb them. Poor

working conditions and low salaries

are frequent complaints in Chinese

factories, resulting in periodic out-

breaks of labor unrest. Demographic

conditions, however, are changing.

The reduction in birthrates since

the 1980s will eventually lead to a

labor shortage, resulting in an up-

ward pressure on workers’ salaries

and inflation in the marketplace.

Discontent has been increasing

in the countryside as well, where

farmers earn only about half the

salary of their urban counterparts

(the government tried to increase

the official purchase price for grain

but rescinded the order when it

became too expensive). China’s entry into the World

Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 was greeted with great

optimism but has been of little benefit to farmers facing

the challenges of cheap foreign imports. Taxes and local

corruption add to their complaints, and land seizures by

the government or by local officials are a major source of

anger in rural communities. In desperation, millions

of rural Chinese have left for the big cities, where many of

them are unable to find steady employment and are forced

to live in squalid conditions in crowded tenements or in

the sprawling suburbs. Millions of others remain on the

farm but attempt to maximize their income by producing

for the market or increasing the size of their families.

Although China’s population control program continues

to limit rural couples to two children, such regulations are

widely flouted despite stringent penalties.

Another factor hindering China ’s rush to economic

advancement is the impact on the environment. With the

rising population, fertile land is in increasingly short supply

(China, with twice the population, now has only two-thirds

as much irrigable land as it had in 1950). Soil erosion is a

major problem, especially in the north, where the desert is

encroaching on farmlands. Water is also a problem. A

massive dam project now under way in the Yangtze River

valley has sparked protests from en vironmentalists, as well

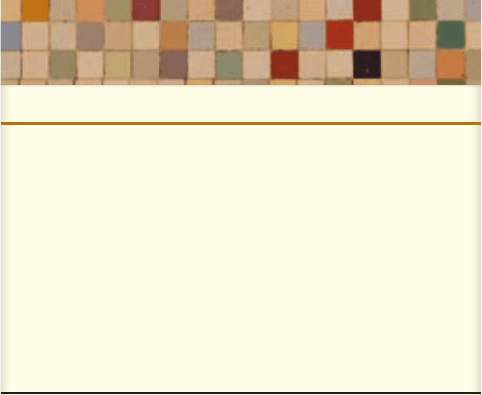

Silk Workers of the World, Unite! In recent years, many critics

have charged that Chinese goods can be marketed at cheap prices abroad

only because factories pay low wages to workers, who must often labor in

abysmal working conditions. The silk industry, which represents one of

China’s key high-end export products, is a case in point. At this factory in

Wuxi, women spend ten hours a day with their hands immersed in boiling

water as they unwind filaments from cocoons onto a spool of silk yarn.

Their blistered red hands testify to the difficulty of their painful task.

c

William J. Duiker

Tourism and the Environment: The Sand Dunes of Dunhuang. For centuries, the Central

Asian commercial hub of Dunhuang was an important stop on the Silk Road. Today, it remains a major

tourist attraction, not only because of the Buddhist relics located in nearby caves, but also for the

strikingly beautiful sand dunes located just outside the modern city. Yet these massive mountains of sand

are also a visual example of China’s growing environmental problem, as the dunes are rapidly encroaching

on nearby pasture lands because of the widespread practice of overgrazing. Soil erosion and the loss of

farm and pasture lands are a major problem for China, as its population continues its rapid increase.

c

William J. Duiker

688 CHAPTER 27 BRAVE NEW WORLD: COMMUNISM ON TRIAL

as from local peoples forced to migrate from the area. The

rate of air pollution is ten times the level in the United

States, contributing to gro wing health conc erns. To add to

the challenge, more than 400,000 new cars and trucks ap-

pear on the country’ s roads each year. Chinese leaders now

face the unc omfortable reality that the pains of industrial-

ization are not exclusive to capitalist countries.

Social Problems

At the root of Marxist-Leninist ideology is the idea of

building a new citizen free from the prejudices, ignorance,

and superstition of the ‘‘feudal’’ era and the capitalist

desire for self-gratification. This new citizen would be

characterized not only by a sense of racial and sexual

equality but also by the selfless desire to contribute his or

her utmost for the good of all.

Women and the Family From the very start, the Chi-

nese Communist government intended to bring an end to

the Confucian legacy in modern China. Women were

given the vote and encouraged to become active in the

political process. At the local level, an increasing number

of women became active in the CCP and in collective

organizations. In 1950, a new marriage law guaranteed

women equal rights with men (see the box above).

VIEWS ON MARRIAGE

One of the major goals of the Communist govern-

ment in China was to reform the tradition of mar-

riage and place it on a new egalitarian basis. In

the following excerpt, a writer with the magazine

China Youth Daily describes the ideal marriage and explains

how socialist marriage differs from its capitalist counterpart.

Q

How, according to this document, will socialist marriage

differ from its capitalist counterpart? What changes in tradi-

tional Chinese practices will take place?

‘‘SERVE THE PEOPLE’’: CHINESE SOCIETY UNDER COMMUNISM 689

Text not available due to copyright restrictions

Most important, perhaps, it permitted women for the

first time to initiate divorce proceedings against their

husbands. Within a year, nearly one million divorces had

been granted.

The regime also undertook to destroy the influence

of the traditional family system. To the Communists,

loyalty to the family, a crucial element in the Confucian

social order, undercut loyalty to the state and to the

dictatorship of the proletariat.

At first, however, the new government moved care-

fully to avoid alienating its supporters in the countryside

unnecessarily. When collective farms were established in

the mid-1950s, payment for hours worked in the form of

ration coupons was made not to the individual but to the

family head, thus maintaining the traditionally dominant

position of the patriarch. When people’s communes were

established in the late 1950s, payments went to the

individual.

During the political radicalism of the Great Leap

Forward, children were encouraged to report to the au-

thorities any comments by their parents that criticized the

system. Such practices continued during the Cultural

Revolution, when children were expected to tell on their

parents, students on their teachers, and employees on

their superiors. Some have suggested that Mao deliber-

ately encouraged such practices to bring an end to the

traditional ‘‘politics of dependency.’’ According to this

theory, historically the famous ‘‘five relationships’’ forced

individuals to swallow their anger and frustration and

accept the hierarchical norms established by Confucian

ethics (known in Chinese as ‘‘to eat bitterness’’). By en-

couraging the oppressed elements in society---the young,

the female, and the poor---to voice their bitterness, Mao

was hoping to break the tradition of dependency. Such

denunciations had been issued against landlords and

other ‘‘local tyrants’’ in the land reform tribunals of the

late 1940s and early 1950s. Later, during the Cultural

Revolution, they were applied to other authority figures

in Chinese society.

Lifestyle Changes The post-Mao era brought a deci-

sive shift away from revolutionary utopianism and back

toward the pragmatic approach to nation building. For

most people, it meant improved living conditions and a

qualified return to family traditions. For the first time,

millions of Chinese saw the prospect of a house or an

urban apartment with a washing machine, television set,

and indoor plumbing. Young people whose parents had

given them patriotic names such as Build the Country,

Protect Mao Zedong, and Assist Korea began to choose

more elegant and cosmopolitan names for their own

children. Some names, such as Surplus Grain or Bring a

Younger Brother, expressed hope for the future.

The new attitudes were also reflected in physical

appearance. For a generation after the civil war, clothing

had been restricted to the traditional baggy ‘‘Mao suit’’ in

olive drab or dark blue, but by the 1980s, young people

craved such fashionable Western items as designer jeans,

trendy sneakers, and sweat suits (or reasonable facsim-

iles). Cosmetic surgery to create a more buxom figure or

a more Western facial look became increasingly common

among affluent young women in the cities. Many had the

epicanthic fold over their eyelids removed or their noses

enlarged---a curious decision in view of the tradition of

referring derogatorily to foreigners as ‘‘big noses.’’

Religious practices and beliefs also changed. As the

government became more tolerant, some Chinese began

to return to the traditional Buddhist faith or to folk

religions, and Buddhist and Taoist temples were once

again crowded with worshipers. Despite official efforts

to suppress its more evangelical forms, Christianity

became increasingly popular; like the ‘‘rice Christians’’

(persons who supposedly converted for economic rea-

sons) of the past, many v iewed it as a sy mbol of success

and cosmopolitanism.

As w ith all social changes, China’s reintegration

into the outside world has had a price. Arranged mar-

riages, nepotism, and mistreatment of females (for ex-

ample, under the one-child rule, parents reportedly

killed female infants to regain the possibility of having a

son) have come back, although such behavior likel y

survived under the cloak of revolutionary purit y for a

generation. Materialistic attitudes are prevalent among

young people, along with a corresponding cynicism

about politics and the CCP (see the comparative essay

‘‘Family and Society in an Era of Change’’ on p. 691).

Expensive weddings are now increasingly common, and

bribery and favoritism are all too frequent. Crime of all

types, including an apparently growing incidence of

prostitution and sex crimes against women, appears to

be on the rise. To discourage sexual abuse, the gov-

ernment now seeks to provide free legal ser v ices for

women liv ing in rural areas.

There is also a price to pay for the trend toward

privatization. Under the Maoist system, the elderly and

the sick were provided with retirement benefits and

health care by the state or by the collective organizations.

Under current conditions, with the latter no longer

playing such a social role and more workers operating in

the private sector, the safety net has been removed. The

government recently attempted to fill the gap by enacting

a social security law, but because of lack of funds, eligi-

bility is limited primarily to individuals in the urban

sector of the economy. Those living in the countryside---

who still represent 60 percent of the population---are

essentially left to their own devices.

690 CHAPTER 27 BRAVE NEW WORLD: COMMUNISM ON TRIAL

China’s Changing Culture

The rise to power of the Communists in 1949 added a new

dimension to the debate over the future of culture in

China. The new leaders rejected the Western attitude of

‘‘art for art’s sake’’ and, like their Soviet counterparts,

viewed culture as an important instrument of indoctrina-

tion. The standard would no longer be aesthetic quality or

the personal preference of the artist but ‘‘ art for life’s sake,’’

whereby culture would serve the interests of socialism.

At first, the new emphasis on socialist realism did not

entirely extinguish the influence of traditional culture.

Mao and his colleagues tolerated---and even encouraged---

efforts by artists to synthesize traditional ideas with

socialist concepts and Western techniques. During the

Cultural Revolution, however, all forms of traditional

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

F

AMILY AND SOCIETY IN AN ERA OF CHANGE

It is one of the paradoxes of the modern world

that at a time of political stability and economic

prosperity for many people in the advanced

capitalist societies, public cynicism about the

system is increasingly widespread. Alienation and drug use are

at dangerously high levels, and the rate of criminal activities

in most areas remains much higher than in the immediate

postwar era.

Although the reasons advanced to explain this paradox vary widely,

many observers place the responsibility for many contemporary so-

cial problems on the decline of the traditional family system. There

has been a steady rise in the percentage of illegitimate birt hs and

single-parent families in countries

throughout the Western world.

In the United States, approximately

half of all marriages end in divorce.

Even in two-parent families, more

and more parents work full time,

leaving the children to fend for

themselves on their return from

school. In many countries in Europe,

the birthrate has dropped to alarm-

ing levels, leading to a severe labor

shortage that is attracting a rising

number of immigrants from other

parts of the world.

Observers point to several

factors as an explanation for these

conditions: the growing emphasis in

advanced capitalist states on an indi-

vidualistic lifestyle devoted to in-

stant gratification, a phenomenon

promoted vigorously by the advertising

media; the rise o f the feminist move-

ment, which has freed women from

the ser v itude imposed on their prede-

cessors, but at the expense of

removing them from full-time responsibility for the care of the

next generation; and the increasing mobility of contemporary life,

which disrupts traditional family ties and creates a sense of

rootlessness and impersonalit y in the individual’s relationship to

the surrounding environment.

This phenomenon is not unique to Western civilization.

The traditional nuclear family is also under attack in many societies

around the world. Even in East Asia, where the Confucian tradition

of family solidarity has been endlessly touted as a major factor in

the region’s economic success, the incidence of divorce and illegiti-

mate births is on the rise, as is the percentage of women in the

workforce. Older citizens frequently complain that the Asian

youth of today are too materialistic, faddish, and steeped in the

individualistic values of the West. Such

criticisms are now voiced in mainland

China as well as in the capitalist

societies around its perimeter (see

Chapter 30).

In societies less exposed to the in-

dividualist lifestyle portrayed so promi-

nently in Western culture, traditional

attitudes about the family continue to

hold sway. In the Middle East, govern-

mental and religious figures seek to

prevent the We stern media from

undermining accepted mores. Success

is sometimes elusive, however, as the

situationinIrandemonstrates. Despite

the zealous guardians of Islamic moral-

ity, many young Iranians are clamoring

for the individual freedoms that have

been denied to them since the Islamic

Revolution took place more than three

decades ago (see Cha pte r 29).

Q

Do you see indications that young

people in China are becoming more

like their counterparts in the West?

China’s ‘‘Little Emperors.’’ To curtail population

growth, Chinese leaders launched a massive family planning

program that restricted urban families to a single child.

Under these circumstances, in conformity with tradition,

sons are especially prized, and some Chinese complain that

many parents overindulge their children, turning them into

spoiled ‘‘little emperors.’’

c

William J. Duiker

‘‘SERVE THE PEOPLE’’: CHINESE SOCIETY UNDER COMMUNISM 691

culture came to be v iewed as reactionary. Socialist realism

became the only acceptable standard in literature, art, and

music. All forms of traditional expression were forbidden.

Nowhere were the dilemmas of the new order more

challenging than in literature. In the heady afterglow of

the Communist victory, many progressive writers sup-

ported the new regime and enthusiastically embraced

Mao’s exhortation to create a new Chinese literature for

the edification of the masses. But in the harsher climate

of the 1960s, many writers were criticized by the party for

their excessive individualism and admiration for Western

culture. Such writers either toed the new line and sup-

pressed their doubts or were jailed and silenced, as was

Ding Ling, the most prominent woman writer in China

during the twentieth century. Born in 1904, she joined

the CCP during the early 1930s and settled in Yan’an,

where she wrote her most famous novel, The Sun Shines

over the Sangan River, which praised the land reform

program. After the Communist victory in 1949, however,

she was criticized for her individualism and outspoken

views. During the Cultural Revolution, she was sentenced

to hard labor. She died in 1981.

After Mao’s death, Chinese culture was finally released

from the shackles of socialist realism. In painting, where

for a decade the only acceptable standard for excellence was

praise for the party and its policies, the new permissiveness

led to a revival of interest in both tra-

ditional and Western forms. Although

some painters continued to blend

Eastern and Western styles, others imi-

tated trends from abr oad, experiment-

ing with a wide range of previously

prohibited art styles, including C ubism

and abstract painting.

In the late 1980s, two avant-garde

art exhibits shocked the Chinese public

and provoked the wrath of the party . An

exhibition of nude paintings, the first ever

held in China, attracted many viewers but

reportedly offended the modesty of

many Chinese. The second was an ex-

hibit presenting the works of various

schools of Modern and Postmodern art.

The event resulted in considerable

commentary and some expressions of

public hostility. After a Communist

critic lambasted the works as promis-

cuous and ideologically reactionary, the

government declared that henceforth it

would regulate all art exhibits.

The limits of freedom of expres-

sion were most apparent in literature.

During the early 1980s, party leaders

encouraged Chinese writers to express their views on the

mistakes of the past, and a new ‘‘literature of the

wounded’’ began to describe the brutal and arbitrary

character of the Cultural Revolution. One of the most

prominent writers was Bai Hua, whose film script Bitter

Love described the life of a young Chinese painter who

joined the revolutionary movement during the 1940s but

was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution when his

work was condemned as counterrevolutionary. The film

depicts the condemnation through a view of a street in

Beijing ‘‘full of people waving the Quotations of Chairman

Mao, all those devout and artless faces fired by a feverish

fanaticism.’’ Driven from his home for posting a portrait

of a third-century

B.C.E. defender of human freedom on a

Beijing wall, the artist flees the city. At the end of the film,

he dies in a snowy field, where his corpse and a semicircle

made by his footprints form a giant question mark.

In criticizing the excesses of the Cultural Revolution,

Bai Hua was only responding to Deng Xiaoping’s appeal

for intellectuals to speak out, but he was soon criticized

for failing to point out the essentially beneficial role of the

CCP in recent Chinese history, and his film was with-

drawn from circulation in 1981. Bai Hua was compelled

to recant his errors and to state that the great ideas of

Mao Zedong on art and literature were ‘‘still of universal

guiding significance today.’’

5

Downtown Beijing. Deng Xiaoping’s policy of Four Modernizations had a dramatic visual effect

on the capital city of Beijing, as evidenced by this photo of skyscrapers thrusting up beyond the walls

of the fifteenth-century Imperial City. Many of these buildings are apartment houses for the capital

city’s growing population, most of them migrants from the countryside looking for employment. The

transformation of Beijing visually highlights the country’s abandonment of traditional styles in favor

of the contemporary global culture.

c

Vittoriano Rastelli/CORBIS

692 CHAPTER 27 BRAVE NEW WORLD: COMMUNISM ON TRIAL

As the attack on Bai Hua illustrates, many party

leaders remained suspicious of the impact that ‘‘decadent’’

bourgeois culture could have on the socialist foundations

of Chinese society, and the official press periodically

warned that China should adopt only the ‘‘positive’’ as-

pects of Western culture (notably, its technology and its

work ethic) and not the ‘‘negative’’ elements such as drug

use, pornography, and hedonism. Conservatives were

especially incensed by the tendency of many writers to

dwell on the shortcomings of the socialist system and to

come uncomfortably close to direct criticism of the role

of the CCP. One such example is the author Mo Yan

(b. 1955), whose novels The Garlic Ballads (1988) and The

Republic of Wine (2000) expose the rampant corruption

of contemporary Chinese society, the roots of which he

attributes to one-party rule.

Another author whose writings fell under the harsh

glare of official disapproval is Zhang Xinxin (b. 1953).

Her controversial novellas and short stories, which ex-

plored Chinese women’s alienation and spiritual malaise,

were viewed by many as a negative portrayal of con-

temporary society, provoking the government in 1984 to

prohibit her from publishing for a year. Determined and

resourceful, Zhang turned to reporting. With a colleague,

she interviewed one hundred ‘‘ordinary’’ people to record

their v iews on all aspects of everyday life.

One of the chief targets of China’s recent ‘‘spiritual

civilization’’ campaign is author Wang Shuo (b. 1958),

whose writings have been banned for exhibiting a sense of

‘‘moral decay.’’ In his novels Playing for Thrills (1989) and

Please Don’t Call Me Human (2000), Wang highlighted

the seamier side of contemporary urban society, peopled

with hustlers, ex-convicts, and other assorted hooligans.

Spiritually depleted, hedonistic, and amoral in their ap-

proach to life, his characters represent the polar opposite

of the socialist ideal.

CONCLUSION

FOR FOUR DECADES after the end of World War II, the world’s

two superpowers competed for global hegemony. The Cold War

became the dominant feature on the international scene and

determined the internal politics of many countries around the

world as well.

By the early 1980s, some of the tension had gone out of the

conflict as it appeared that both Moscow and Washington had

learned to tolerate the other’s existence. Skeptical minds even

suspected that both countries drew benefits from their mutual rivalry

and saw it as an advantage in carrying on their relations with friends

and allies. Few suspected that the Cold War, which had long seemed a

permanent feature of world politics, was about to come to an end.

What brought about the collapse of the Soviet Empire? Some

observers argue that the ambitious defense policies adopted by the

Reagan administration forced Moscow into an arms race it could

not afford, which ultimately led to a collapse of the Soviet economy.

Others suggest that Soviet problems were more deep-rooted and

would have ended in the disintegration of the Soviet Union even

without outside stimulation. Both arguments have some validity,

but the latter is surely closer to the mark. For years, if not decades,

leaders in the Kremlin had disguised or ignored the massive

inefficiencies of the Soviet system. In the 1980s, the perceptive

Mikhail Gorbachev tried to save the system by instituting radical

reforms. By then, however, it was too late.

Why has communism survived in China, albeit in a

substantially altered form, when it failed in Eastern Europe and the

Soviet Union? One of the primary factors is probably cultural.

Although the doctrine of Marxism-Leninism originated in Europe,

many of its main precepts, such as the primacy of the community

over the individual and the denial of the concept of private

property, run counter to trends in Western civ ilization. This

inherent conflict is especially evident in the societies of central

Europe, which were strongly influenced by Enlightenment phi-

losophy and the Industrial Revolution. These forces were weaker in

the countries farther to the east, but both had begun to penetrate

tsarist Russia by the end of the nineteenth century.

By contrast, Marxism-Leninism found a more receptive

climate in China and other countries in the region influenced by

Confucian tradition. In its political culture, the Communist

system exhibits many of the same characteristics as traditional

Confucianism---a single truth, an elite governing class, and an

emphasis on obedience to the community and its governing

representatives---while feudal attitudes regarding female inferiority,

loyalty to the family, and bureaucratic arrogance are hard to break.

On the surface, China today bears a number of uncanny similarities

to the China of the past.

Yet these similarities should not blind us to the real changes

that are taking place in Chinese society today. Although the

youthful protesters in Tiananmen Square were comparable in some

respects to the reformist elements of the early republic, the China of

today is fundamentally different from that of the early twentieth

century. Literacy rates and the standard of livi ng are far higher, the

pressures of outside powers are less threatening, and China has

entered its own industrial and technological revolution. For many

Chinese, independent talk radio and the Internet are a greater

source of news and views than are the official media. Where Sun

Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek, and even Mao Zedong broke their lances

on the rocks of centuries of tradition, poverty, and ignorance,

China’s present leaders rule a country much more aware of the

world and its place in it.

CONCLUSION 693

SUGGESTED READING

Russ ia and the Soviet Union Forageneralviewofmodern

Russia, see M. Malia, Russia Under Western Eyes (Cambridge, Mass.,

1999), and M. T. Poe, The Russian Moment in World History

(Princeton, N.J., 2003). On the Khrushchev years, see W. Taubman,

Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (New York, 2004). For an

overview of the Soviet era, see R. J. Hill, The Soviet Union: Politics,

Economics, and Society, 2nd ed. (London, 1989); M. Lewin, The

Gorbachev Phenomenon (Berkeley, Calif., 1988); G. Hosking, The

Awakening of the Soviet Union (London, 1990); and S. White,

Gorbachev and After (Cambridge, 1991). For an inquiry into the

reasons for the Soviet collapse, see R. Conquest, Reflections on a

Ravaged Century (New York, 1999), and R. Strayer, Why Did the

Soviet Union Collapse? Understanding Historical Change (New

York, 1998).

Soviet Satellites For a general study of the Soviet satellites

in Eastern Europe, see S. Fischer-Galati, EasternEuropeinthe

1980s (London, 1981). Additional studies on the recent histor y

of these countries in clude T. G. Ash, The Polish Revolution:

Solidarity (New York, 1984); B. Kovr ig, Communism in Hungary

from Kun t o K

ad

ar (Stanford, Calif., 1979); T. G. Ash, The

Magic Lantern: The Revolution of ’89 Witnessed in Warsaw,

Budapest, Ber li n, and Prague (New York, 1990); and S. Ramet,

Nationalism a nd Federalism i n Yugoslavia (Blo omington, Ind.,

1992).

China After World War II A number of useful surveys

deal with China after World War II. The most comprehensive

treatment of the Communist period is M. Meisner, Mao’s China

and After: A Histor y of the People’s Republic (New York, 1999).

Also see R. Macfarquhar, ed., The Politics of China: T he Eras

of Mao and Deng (Cambridge, 1997). Interesting documents

can be found in M. Selden, ed., The People’s Republic of Ch ina:

A Do cumentar y Histor y of Revolutionar y Change (New York,

1978).

Communist China There are countless specialized studies on

various aspects of the Communist period in China. The Cultural

Revolution is treated dramatically in S. Karnow, Mao and China:

Inside China’s Cultural Revolution (New York, 1972). For

individual accounts of the impact of the revolution on people’s lives,

see the celebrated book by Nien Cheng, Life and Death in

Shanghai (New York, 1986). A recent critical biography of China’s

‘‘Great Helmsman’’ is J. Chang and J. Halliday, Mao: The Unknown

Story (New York, 2005).

Post-Mao China On the early post-Mao period, see O. Schell,

To Get Rich Is Glorious (New York, 1986), and the sequel, Discos

and Democracy: China in the Throes of Reform (New York, 1988).

The 1989 demonstrations and their aftermath are chronicled in

L. Feigon’s eyewitness account, China Rising: The Meaning of

Tiananmen (Chicago, 1990), and D. Morrison, Massacre in Beijing

(New York, 1989). Documentary materials relating to the events

TIMELINE

1945

1955 1965 1975 1985 1995 2005 2010

Soviet Union

and Russia

Eastern

Europe

China

Death of Stalin and

emergence of

Khrushchev

“Prague Spring”

Creation of People’s Republic

of China

Death of Mao Zedong

Period of New

Democracy

Revolutions of Eastern Europe

Era of Brezhnev Dissolution of the

Soviet Union

The

Gorbachev

years

Communist governments

established in Eastern Europe

Tiananmen Square incident

Great Leap Forward

Great Proletarian

Cultural Revolution

Era of “Four Modernizations”

Presidency of

Jiang Zemin

Hu Jintao becomes

president

Rise to power of

Deng Xiaoping

Yeltsin era

694 CHAPTER 27 BRAVE NEW WORLD: COMMUNISM ON TRIAL

of 1989 are chronicled in A. J. Nathan and P. Link, eds., The

Tiananmen Papers (New York, 2001). Subsequent events are

analyzed in J. Fewsmith, China Since Tiananmen: The Politics

of Transition (Cambridge, 2001). On China’s challenge from the

process of democratization, see J. Gittings, The Changing Face

of China: From Mao to Market (Oxford, 2005). Also see T. Saich,

Governance and Politics in China (New York, 2002). China’s

evolving role in the world is traced in S. Shirk, China: Fragile

Superpower (Oxford, 2007).

Chinese Literature and Art For a comprehensive

introduction to twentieth-century Chinese literature, consult

E. Widmer and D. Der-Wei Wang, eds., From May Fourth to June

Fourth: Fiction and Film in Twentieth-Century China (Cambridge,

Mass., 1993), and J. Lau and H. Goldblatt, The Columbia

Anthology of Modern Chinese Literature (New York, 1995). To

witness daily life in the mid-1980s, see Z. Xinxin and S. Ye, Chinese

Lives: An Oral History of Contemporary China (New York, 1987).

For the most comprehensive analysis of twentieth-century Chinese

art, consult M. Sullivan, Arts and Artists of Twentieth-Century

China (Berkeley, Calif., 1996).

Women in China For a discussion of the women’s movement

in China during the postwar period, see J. Stacey, Patriarchy and

Socialist Revolution in China (Berkeley, Calif., 1983), and M. Wolf,

Revolution Postponed: Women in Contemporary China (Stamford,

Conn., 1985). Gender issues are treated in B. Entwistle and G. E.

Henderson, eds., Redrawing Boundaries: Work, Households, and

Gender in China (Berkeley, Calif., 2000).

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

CONCLUSION 695