Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

696

CHAPTER 28

EUROPE AND THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE SINCE 1945

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

Recovery and Renewal in Europe

Q

What problems have the nations of Western Europe

faced since 1945, and what steps have they taken to try

to solve these problems? What problems have Eastern

European nations faced since 1989?

Emergence of the Superpower: The United States

Q

What political, social, and economic changes has the

United Stat es experienced since 1945?

The Development of Canada

Q

What political, social, and economic developments

has Canada experienced since 1945?

Latin America Since 1945

Q

What problems have the nations of Latin America faced

since 1945, and what role has Marxist ideology played

in their efforts to solve these problems?

Society and Culture in the Western World

Q

What major social, cultural, and intellectual develop-

ments have occurred in Western Europe and North

America since 1945?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

What are the similarities and differences between the

major political, economic, and social developments in

the fir st half of the twentieth century and those in the

second half of the century?

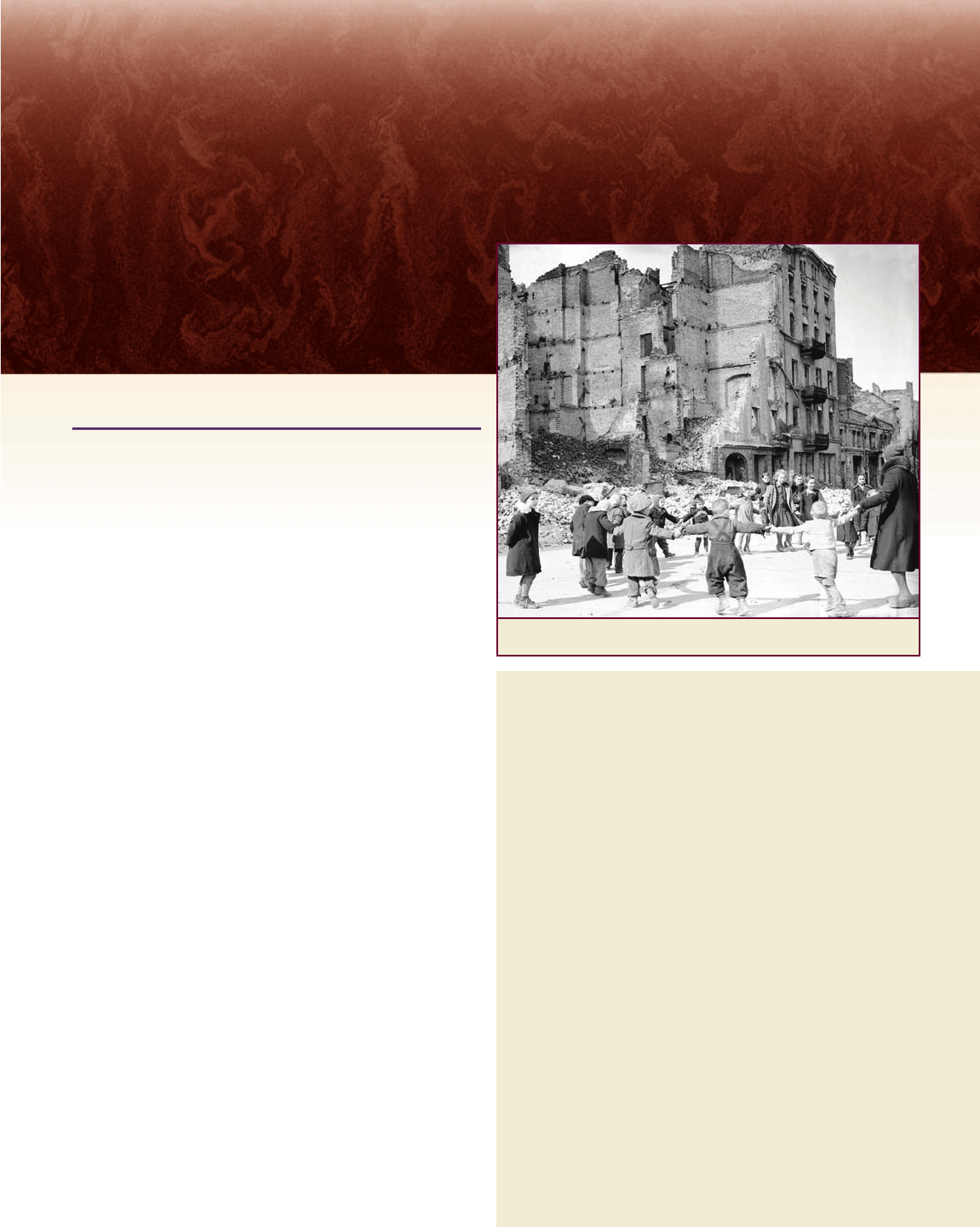

Children play amid the ruins of Warsaw, Poland, at the end of World War II.

THE END OF WORLD WAR II in Europe had been met with

great joy. One visitor in Moscow reported, ‘‘I looked out of the

window [at 2

A.M.], almost ever ywhere there were lights in the

windows---people were staying awake. Everyone embraced everyone

else, someone sobbed aloud.’’ But after the victory parades and cele-

brations, Europeans awoke to a devastating realization: their civiliza-

tion was in ruins. Almost 40 million people (both soldiers and

civilians) had been killed over the last six years. Massive air raids

and artillery bombardments had reduced many of the great cities of

Europe to heaps of rubble. The Polish capital of Warsaw had been

almost completely obliterated. An American general described

Berlin: ‘‘Wherever we looked, we saw desolation. It was like a city of

the dead. Suffering and shock were visible in every face. Dead bodies

still remained in canals and lakes and were being dug out from

under bomb debris.’’ Many Europeans were homeless.

Between 1945 and 1970, Europe not only recovered from the

devastating effects of World War II but also experienced an eco-

nomic resurgence that seemed nothing less than miraculous. Eco-

nomic growth and virtually full employment continued so long that

the first postwar recession, in 1973, came as a shock to Western

Europe. It was short-lived, however, and economic growth returned.

After the collapse of Communist governments in the revolutions

697

c

Bettmann (Reginald Kenny)/CORBIS

Recovery and Renewal in Europe

Q

Focus Questions: What problems have the nations

of Western Europe faced since 1945, and what steps

have they taken to try to sol ve thes e problems ? What

problems have Eastern European nations faced since

1989?

All the nations of Europe faced similar problems at the

end of World War II. Above all, they needed to rebuild

their shattered economies. Yet, within a few years after the

defeat of Germany and Italy, an incredible economic

revival brought renewed growth to Western Europe.

Western Europe: The Triumph of Democracy

With the economic aid of the Marshall Plan, the countries

of Western Europe recovered relatively rapidly from the

devastation of World War II. Between the early 1950s and

late 1970s, industrial production surpassed all previous

records, and Western Europe experienced virtually full

employment.

France: From de Gaulle to New Uncertainties The

history of France for nearly a quarter century after

the war was dominated by one man---Charles de Gaulle

(1890--1970). Initially, he had withdrawn from politics,

but in 1958, frightened by the bitter divisions within

France caused by the Algerian crisis (see Chapter 29), the

panic-stricken leaders of the Fourth Republic offered to

let de Gaulle take over the government and revise the

constitution.

De Gaulle’s constitution for the Fifth Republic greatly

enhanced the power of the office of president, who now

had the right to choose the prime minister, dissolve par-

liament, and supervise both defense and foreign policy. As

the new president, de Gaulle sought to return France to a

position of great power. With that goal in mind, he in-

vested heavily in the nuclear arms race. France exploded

its first nuclear bomb in 1960. Despite his successes, de

Gaulle did not really achieve his ambitious goals; in truth,

France was too small for such global ambitions.

During de Gaulle’s presidency, France became a

major industrial producer and exporter, but problems

remained. The expansion of traditional industries, such as

coal, steel, and railroads, which had all been nationalized,

led to large government deficits. The cost of living in-

creased faster than in the rest of Europe. Increased dis-

satisfaction led in May 1968 to a series of student protests,

followed by a general strike by the labor unions. Although

he restored order, de Gaulle resigned from office in

April 1969 and died the next year.

The worsening of France’s economic situation in the

1970s brought a shift to the left politically. By 1981, the

Socialists had become the dominant party in the National

Assembly, and the Socialist leader, Franc¸ois Mitterrand

(1916--1995), was elected president. Mitterrand passed a

number of measures to aid workers: an increased mini-

mum wage, expanded social benefits, a mandatory fifth

week of paid vacation for salaried workers, and a thirty-

nine-hour workweek. The victory of the Socialists led

them to enact some of their more radical reforms: the

government nationalized the major banks, the space and

electronics industries, and important insurance firms.

The Socialist policies, however, largely failed, and

within three years, a decline in support caused the Mit-

terrandgovernmenttoreturnsomeoftheeconomyto

private enterprise. But France’s economic decline contin-

ued, and in 1993, a coalition of conservative parties won

80 percent of the seats. The move to the right was

strengthened when the conservative mayor of P aris,

Jacques Chirac (b. 1932), was elected president in May 1995

and reelected in 2002. Resentment against foreign-born

residents led many French voters to call for restrictions on

all new immigration. Chirac himself pursued a plan of

sending illegal immigrants back to their home countries.

698 CHAPTER 28 EUROPE AND THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE SINCE 1945

of 1989, a number of Eastern European states sought to create mar-

ket economies and join the military and economic unions first

formed by Western European states.

The most significant factor after 1945 was the emergence of the

U nited States as the world’ s richest and most powerful nation.

American prosperity reached new heights in the two decades after

World War II, but a series of economic and social problems---including

racial division and staggering budget deficits---have given the nation

plenty of internal matters to grapple with over the past half century.

To the south of the U nited States lay the vast world of Latin

America, with its own unique heritage. Although some Latin

Americans in the nineteenth century had looked to the United States

as a model for their own development, in the twentieth century, many

attacked the United States for its military and economic domination of

Central and South America. At the same time, many Latin American

countries struggled with economic and political instability .

In addition to the transformation from Cold War to post--Cold

War realities, other changes were shaping the Western outlook. The

demographic face of European countries changed as massive num-

bers of immigrants created more ethnically diverse populations.

New artistic and intellectual currents, the continued advance of sci-

ence and technology, the effort to come to grips with environmental

problems, the surge of the women’s liberation movement---all spoke

of a vibrant, ever-changing world. At the same time, a devastating

terrorist attack in the United States in 2001 made the Western

world vividly aware of its vulnerability to international terrorism.

A global financial collapse in 2008 also presented new challenges to

both Western and world economic stability.

In the fall of 2005, however, antiforeign sentiment

provoked a backlash of its own, as young Muslims in the

crowded suburbs of Paris rioted against dismal living

conditions and the lack of employment opportunities for

foreign residents in France. Tensions between the Muslim

community and the remainder of the French population

became a chronic source of social unrest throughout the

country---an unrest that Nicolas Sarkozy (b. 1955), elected

as president in 2007, promised to address.

From West Germany to Germany Under the pressures

of the Cold War, the three western zones of Germany

were unified as the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949.

Konrad Adenauer (1876--1967), the leader of the

Christian Democratic Union (CDU), served as chancellor

from 1949 to 1963 and became the Federal Republic’s

‘‘founding hero.’’

Adenauer’s chancellorship is largely associated with

the resurrection of the West German economy, often re-

ferred to as the ‘‘economic miracle.’’ It was largely guided

by the minister of finance, Ludwig Erhard. Although West

Germany had only 52 percent of the territory of prewar

Germany, by 1955 the West German gross domestic

product exceeded that of prewar Germany. Unemploy-

ment fell from 8 percent in 1950 to 0.4 percent in 1965.

After the Adenauer era, German voters moved polit-

ically from the center-right of the Christian Democrats to

the center-left: in 1969, the Social Democrats became the

leading party. The first Social Democratic chancellor was

Willy Brandt (1913--1992), who was especially successful

with his ‘‘opening toward the east’’ (known as Ostpolitik),

for which he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1972. On

March 19, 1971, Brandt worked out the details of a treaty

with East Germany (the former Russian zone) that led to

greater cultural, personal, and economic contacts be-

tween West and East Germany.

In 1982, the Christian Democratic Union of Helmut

Kohl (b. 1930) formed a new center-right government.

Kohl was a clever politician who benefited greatly from an

economic boom in the mid-1980s and the 1989 revolu-

tion in East Germany, which led to the reunification of

the two Germanies, making the new Germany, with its

79 million people, the leading power in Europe. Reuni-

fication brought immediate political dividends to the

Christian Democrats, but all too soon, the realization set

in that the revitalization of eastern Germany would take

far more money than was originally thought. Kohl’s

government soon faced the politically undesirable pros-

pect of raising taxes substantially. Moreover, the virtual

collapse of the economy in eastern Germany led to ex-

tremely high unemployment and severe discontent. One

response was the return to power of the Social Democrats

under the leadership of Gerhard Schroeder (b. 1944) in

elections in 1998. But Schroeder failed to cure Germany’s

economic woes, and, as a result of elections in 2005,

Angela Merkel (b. 1954), leader of the Christian

Democrats, became the first female chancellor in German

history.

The Decline of Great Britain The end of World War II

left Britain with massive economic problems. In elections

held immediately after the war, the Labour Party over-

whelmingly defeated Winston Churchill’s Conservatives.

Labour had promised far-reaching reforms, particularly

in the area of social welfare, and in a country with a

tremendous shortage of consumer goods and housing, its

platform was quite appealing. The new Labour govern-

ment under Clement Attlee (1883--1967) proceeded to

turn Britain into a modern welfare state.

The process began with the nationalization of the

Bank of England, the coal and steel industries, public

transportation, and public utilities, such as electricity and

gas. In 1946, the new government established a compre-

hensive social security program and nationalized medical

insurance, thereby enabling the state to subsidize the un-

employed, the sick, and the aged. A health act established

a system of socialized medicine that forced doctors and

dentists to work with state hospitals, although private

practice could be maintained. The British welfare state

became the norm for most European nations after the war.

Continuing economic problems, however, brought

the Conservatives back into power from 1951 to 1964.

Although they favored private enterprise, the Con-

servatives accepted the welfare state. By now the British

economy had recovered from the war, but the slow rate of

its recovery reflected a long-term economic decline. At

the same time, as the influence of the United States and

the Soviet Union continued to rise, Britain’s ability to

play the role of a world power declined substantially.

Between 1964 and 1979, Conservatives and Labour al-

ternated in power, but neither party was able to deal with

Britain’s ailing economy.

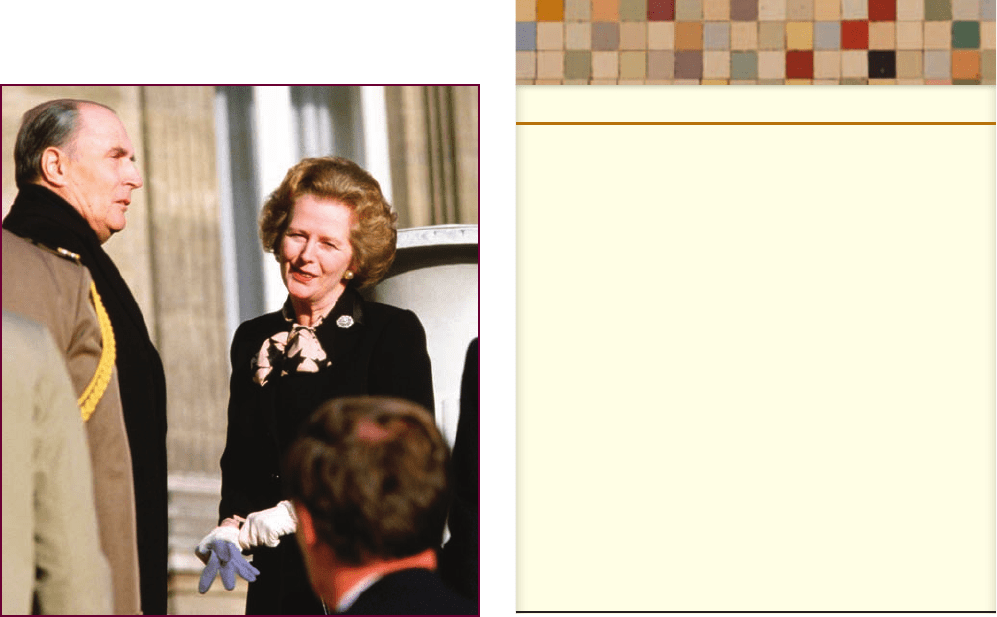

In 1979, the Conservatives returned to power under

Margaret Thatcher (b. 1925), who became the first woman

to serve as prime minister in British history (see the box

on p. 700). The ‘‘Iron Lady,’’ as she was called, broke the

power of the labor unions, but she was not able to elim-

inate the basic components of the social welfare system.

‘‘Thatcherism,’’ as her economic policy was termed, im-

proved the British economic situation, but at a price. The

south of England, for example, prospered, but the old

industrial areas of the Midlands and north declined and

were beset by high unemployment and poverty.

Margaret Thatcher dominated British politics in the

1980s. But in 1990, Labour’ s fortunes revived when

Thatcher’s government attempted to replace local property

RECOVERY AND RENEWAL IN EUROPE 699

taxes with a flat-rate tax payable by every adult. Many

British subjects argued that this was nothing more than a

poll tax that would allow the rich to get away with paying

the same rate as the poor. In 1990, Thatcher resigned, and

later, in new elections in 1997, the Labour Party won a

landslide victory . The new prime minister, Tony Blair

(b. 1953), was a moderate whose youthful energy imme-

diately instilled new vigor on the political scene. Blair was

one of the prominent leaders in forming an international

coalition against terrorism after the terrorist attack on the

U nited States in 2001. Four years later , however, his support

of the U .S. war in Iraq, when a majority of Britons opposed

it, caused his popularity to plummet. In the summer of

2007, he stepped down and allowed the new Labour Party

leader Gordon Brown (b. 1951) to become prime minister .

Eastern Europe After Communism

The fall of Communist governments in Eastern Europe

during the revolutions of 1989 brought a wave of eu-

phoria to Europe. The new structures meant an end to a

postwar European order that had been imposed on un-

willing peoples by the victorious forces of the Soviet

Union (see Chapter 26). In 1989 and 1990, new govern-

ments throughout Eastern Europe worked diligently to

scrap the remnants of the old system and introduce the

democratic procedures and market systems they believed

would revitalize their scarred lands. But this process

proved to be neither simple nor easy. Nevertheless, by the

beginning of the twenty-first century, many of these

states, especially Poland and the Czech Republic, were

MARGARET THATCHER:ENTERING A MAN’S WORLD

In 1979, Margaret Thatcher became the first

woman to serve as Britain’s prime minister and

went on to be its longes t-serving prime minister

as well. In this excerpt from her autobiography,

Thatcher describes how she was interviewed by Conservative

Party officials when they first considered her as a possible

candidate for Parliament as a representative from Dartford.

Thatcher ran for Parliament for the first time in 1950; she lost

but did increase the Conservative vote total in the district by

50 percent over the previous election.

Margaret Thatcher, The Path to Power

And they did [consider her]. I was invited to have lunch with John

Miller and his wife, Phee, and the Dartford Woman’s Chairman,

Mrs. Fletcher, on the Saturday on Llandudno Pier. Presumably, and

in spite of any reservations about the suitability of a woman candi-

date for their seat, they liked what they saw. I certainly got on well

with them. The Millers were to become close friends and I quickly

developed a healthy respect for the dignified Mrs. Fletcher. After

lunch we walked back along the pier to the Conference Hall in good

time for a place to hear Winston Churchill give the Party Leader’s

speech. It was the first we had seen of him that week, because in

those days the Leader did not attend the Conference itself, appearing

only at a final rally on the Saturday. Foreign affairs naturally domi-

nated his speech---it was the time of the Berlin blockade and the

Western airlift---and his message was somber, telling us that only

American nuclear weapons stood between Europe and communist

tyranny and warning of ‘‘what seems a remorselessly approaching

third world war.’’

I did not hear from Dartford until December, when I was asked

to attend an interview at Palace Chambers, Bridge Street---then

housing Conservative Central Office---not far from Parliament itself.

With a large number of other hopefuls I turned up on the evening

of Thursday 30 December for my first Selection Committee. Very

few outside the political arena know just how nerve-racking such

occasions are. The interviewee who is not nervous and tense is very

likely to perform badly: for, as any chemist will tell you, the adrena-

line needs to flow if one is to perform at one’s best. I was lucky in

that at Dartford there were some friendly faces around the table,

and it has to be said that on such occasions there are advantages as

well as disadvantages to being a young woman making her way in

the political world.

I found myself short-listed, and was asked to go to Dartford it-

self for a further interview. Finally, I was invited to the Bull Hotel in

Dartford on Monday 31 January 1949 to address the Association’s

Executive Committee of about fifty people. As one of five would-be

candidates, I had to give a fifteen-minute speech and answer ques-

tions for a further ten minutes.

It was the questions which were more likely to cause me trou-

ble. There was a good deal of suspicion of woman candidates, par-

ticularly in what was regarded as a tough industrial seat like

Dartford. This was quite definitely a man’s world into which not

just angels feared to tread. There was, of course, little hope of win-

ning it for the Conservatives, thoug h this is never a point that the

prospective candidate even in a Labour seat as safe as Ebbw Vale

would be advised to make. The Labour majority was an all but un-

scalable 20,000. But perhaps this unspoken fact turned to my favour.

Why not take the risk of adopting the young Margaret Roberts?

There was not much to lose, and some good publicity for the Party

to gain.

The most reliable sign that a political occasion has gone well is

that you have enjoyed it. I enjoyed that evening at Dartford, and the

outcome justified my confidence. I was selected.

Q

In this account, is Margaret Thatcher’s being a woman more

important to her or to others? Why would this disparity exist?

700 CHAPTER 28 EUROPE AND THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE SINCE 1945

making a successful transition to both free markets and

democracy.

The revival of the post--Cold War Eastern European

states was evident in their desire to join both the North

Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European

Union (EU), the two major Cold War institutions of

Western European unity. In 1997, Poland, the Czech

Republic, and Hungary became full members of NATO. In

2004, ten nations---including Hungary, Poland, the Czech

Republic, Slovenia, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania---joined

the EU, and Romania and Bulgaria joined in 2007.

Yet not all are convinced that inclusion in European

integration is a good thing. Eastern Europeans fear that

their countries will be dominated by investment from

their prosperous neighbors. The global economic crisis of

2008--2009 has been particularly troublesome for many

Eastern European nations.

The Disintegration of Yugoslavia From its beginning

in 1919, Yugoslavia had been an artificial creation. After

World War II, the dictatorial Marshal Tito had managed

to hold together the six republics and two autonomous

provinces that constituted Yugoslavia. After his death in

1980, no strong leader emerged, and at the end of the

1980s, Yugoslavia was caught up in the reform move-

ments sweeping through Eastern Europe.

After negotiations among the six republics failed,

Slovenia and Croatia declared their independence in June

1991. This action was opposed by Slobodan Milos

ˇ

evi

c

(1941--2006), the leader of the province of Serbia. He

asserted that these republics could only be independent

if new border arrangements were made to accommo-

date the Serb minorities in those republics who did not

want to live outside the boundaries of Serbia. Serbian

forces attacked both new states and, although unsuc-

cessful against Slovenia, captured one-third of Croatia’s

territory.

The international recognition of independent Slovenia

and Croatia in 1992 and of Macedonia and Bosnia and

Herzegovina soon thereafter did not deter the Ser bs, who

now turned their guns on Bosnia. By mid-1993, Serbian

forces had acquired 70 percent of Bosnian territory. The

Serbian policy of ethnic cleansing---killing or forcibly

removing Bosnian Muslims from their lands---revived

memories of Nazi atrocities in World War II. This ac-

count by one Muslim sur vivor from the town of Sre-

brenica is eerily reminiscent of the activities of the Nazi

Einsatzgruppen (see Chapter 25):

When the truck stopped, they told us to get off in groups of

five. We immediately heard shooting next to the trucks. ...

About ten Serbs with automatic rifles told us to lie down on

the ground face first. As we were getting down, they started

to shoot, and I fell into a pile of corpses. I felt hot liquid

Margaret Thatcher. Great Britain’s first female prime minister,

Margaret Thatcher was a strong leader who dominated British politics in

the 1980s and served in the post longer than any man. This picture of

Thatcher was taken during a meeting with French president Franc¸ois

Mitterrand in 1986.

c

Peter Turnley/CORBIS

CHRONOL OGY

Western Europe

Welfare state emerges in Great Britain 1946

Konrad Adenauer becomes chancellor of West Germany 1949

Charles de Gaulle reassumes power in France 1958

Student protests in France 1968

Willy Brandt becomes chancellor of West Germany 1969

Margaret Thatcher becomes prime minister

of Great Britain

1979

Franc¸ois Mitterrand becomes president of France 1981

Helmut Kohl becomes chancellor of West Germany 1982

Reunification of Germany 1990

Conservative victory in France 1993

Election of Chirac 1995

Labour Party victory in Great Britain 1997

Social Democratic victory in Germany 1998

Angela Merkel becomes chancellor of Germany 2005

Nicolas Sarkozy becomes president of France 2007

Gordon Brown becomes prime minister of Great Britain 2007

R

ECOVERY AND RENEWAL IN EUROPE 701

running down my face. I realized that I was only grazed.

As they continued to shoot more groups, I kept on squeezing

myself in between dead bodies.

1

As the fighting spread, European nations and the

United States began to intervene to stop the bloodshed,

and in the fall of 1995, a fragile cease-fire agreement was

reached. An international peacekeeping force was sta-

tioned in the area to prevent further hostilities.

P eac e in Bosnia, however, did not bring peace to

Yugoslavia. A new war erupted in 1999 over Kosovo ,

an autonomous province within the Serbian republic.

Kosovo’s inhabitants were mainly ethnic Albanians, but the

province was also home to a Serbian minority . In 1989,

Yugoslav president Milos

ˇ

evi

c stripped K oso v o of its au-

tonomous status. Four years later, some groups of ethnic

Albanians founded the K oso vo Liberation Army (KLA)

and began a campaign against Serbian rule in Kosovo .

When Serb forces began to massacre ethnic Albanians in

an effort to crush the KLA, the United States and its NATO

allies mounted a bombing campaign that forced Milos

ˇ

evi

c

to stop. In the fall elections of 2000, Milos

ˇ

evi

c himself was

ousted from power, and he was later put on trial by an

international tribunal for war crimes against humanity for

his ethnic cleansing policies throughout Yugoslavia’s dis-

integration. He died in 2006 during that trial.

The fate of Bosnia and Kosovo has not yet been fi-

nally determined. NATO troops remain in Bosnia, try ing

to keep the peace, while other NATO military forces

maintain an uneasy peace in Kosovo.

The last political vestige of Yugoslavia ceased to exist

in 2004 when the new national government officially re-

named the truncated country Serbia and Montenegro.

Two years later, Montenegrins voted in favor of indepen-

dence. Thus, by 2006, all six republics cobbled together to

form Yugoslavia in 1918 were once again independent

nations.

The New Russia: From Empire to Nation

Soon after the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991,

a new era began in Russia w ith the presidency of Boris

Yeltsin. A new constitution created a two-chamber par-

liament and established a strong presidency. During the

mid-1990s, Yeltsin was able to maintain a precarious grip

on power while seeking to implement reforms that would

set Russia on a firm course toward a pluralistic political

system and a market economy. But the new post-

Communist Russia remained as fragile as ever.

Burgeoning economic inequality and rampant corruption

aroused widespread criticism and shook the confidence of

the Russian people in the superiority of the capitalist

system over the one that existed under Communist rule.

A nagging war in the Caucasus---where the people of

Chechnya resolutely sought national independence from

Russia---drained the government budget and exposed the

decrepit state of the once vaunted Red Army. In presi-

dential elections held in 1996, Yeltsin was reelected, but

his precarious health raised serious questions about the

future of the country.

The Putin Era At the end of 1999, Yeltsin suddenly

resigned his office and was replaced by Vladimir Putin

(b. 1952), a former member of the KGB. Putin vowed to

bring an end to the rampant corruption and inexperience

that permeated Russian political culture and to strengthen

the role of the central government in managing the affairs

of state.

Putin also vowed to bring the breakaway state of

Chechnya back under Russian authority and to assume a

more assertive role in international affairs. The new

president took advantage of growing public anger at

Western plans to expand the NATO alliance into Eastern

Europe to restore Russia’s position as an influential force

in the world.

Putin attempted to deal with the chronic problems in

Russian society by centralizing his control over the system

and by silencing critics---notably in the Russian media.

Such moves aroused unease among many observers in the

West. But there was widespread concern in Russia about

the decline of the social order---marked by increases

in alcoholism, sexual promiscuity, and criminal activities

and the disintegration of the traditional family system---

and many of Putin’s compatriots supported his attempt

to restore a sense of pride and discipline in Russian

society.

Putin’s popularity among the Russian people was also

strengthened by Russia’s growing prosperity at the be-

ginning of the twenty-first century. During his presi-

dency, Putin made significant economic reforms while

rising oil prices strengthened the Russian economy, which

grew dramatically until the 2008--2009 global economic

crisis.

After serving two terms as president, Putin was un-

able to run for a third term because the Russian consti-

tution mandates term limits. After the victory of his

chosen successor, Dmitry Medvedev, in the 2008 presi-

dential elections, however, Putin was appointed as prime

minister, a position that enables him to continue to ex-

ercise considerable power.

The Unification of Europe

As we saw in Chapter 26, the divisions created by the Cold

War led the nations of Western Europe to seek military

security by forming NATO in 1949. The destructiveness of

702 CHAPTER 28 EUROPE AND THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE SINCE 1945

two world wars, however, caused many thoughtful

Europeans to consider the need for some additional form

of unity.

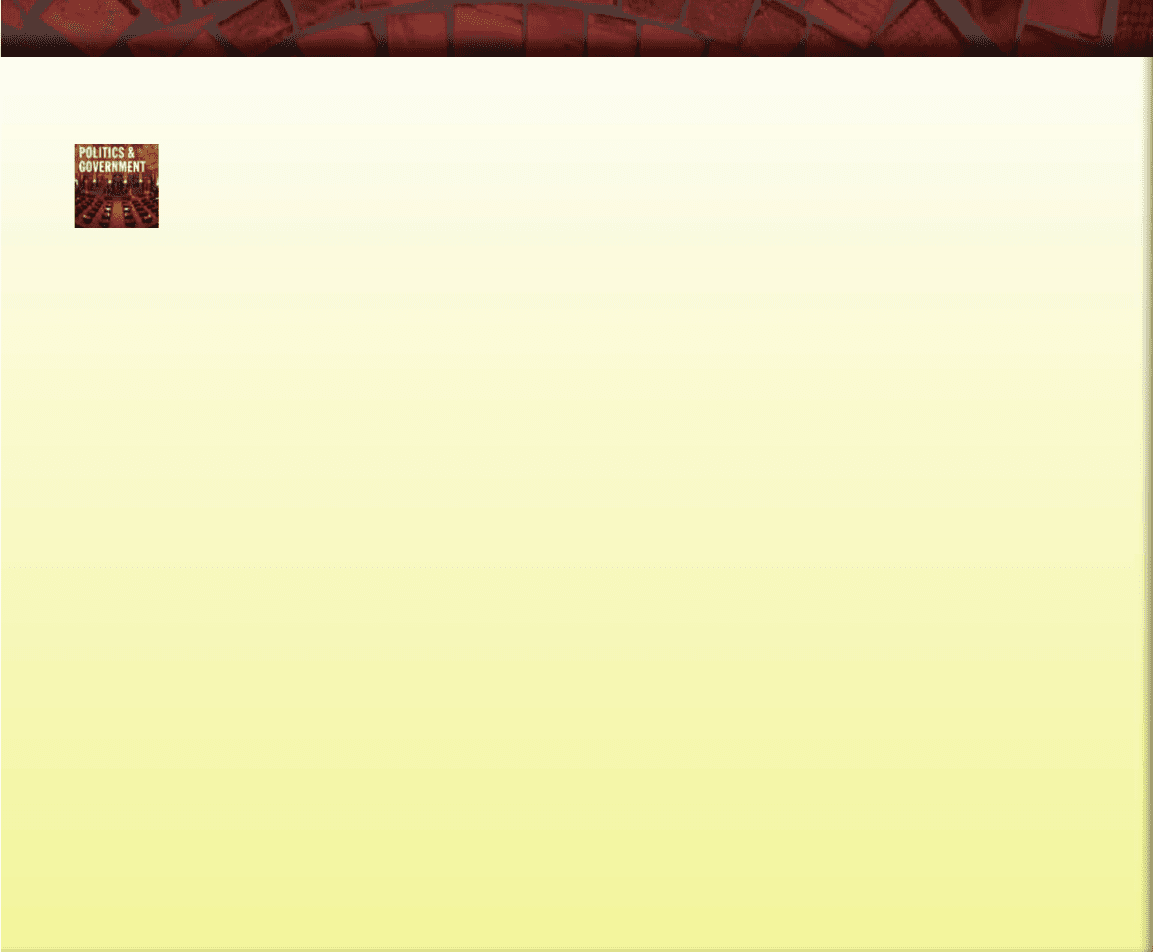

In 1957, France, West Germany, the Benelux coun-

tries (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg), and

Italy signed the Treaty of Rome, which created the

European Economic Community (EEC). The EEC elim-

inated customs barriers for the six member nations and

created a large free-trade area protected from the rest of

the world by a common external tariff. All the member

nations benefited economically. In 1973, Great Britain,

Ireland, and Denmark gained membership in what now

was called the European Community (EC). Greece joined

in 1981, followed by Spain and Portugal in 1986. In 1995,

Austria, Finland, and Sweden also became members of

the EC.

The European Union The European Community was

an economic union, not a political one. By 2000, the EC

contained 370 million people and constituted the world’s

largest single trading entity, transacting one-fourth of the

world’s commerce. In the 1980s and 1990s, the EC moved

toward even greater economic integration. The Treaty on

European Union, which went into effect on January 1,

1994, turned the European Community into the

European Union, a true economic and monetary union.

One of its first goals was achieved in 1999 with the in-

troduction of a common currency, the euro. On January

1, 2002, the euro officially replaced twelve national cur-

rencies; by 2010, it had been officially adopted by four

additional nations.

In addition to having a single internal market and a

common currency for those sixteen members, the EU has

also established a common agricultural policy, which

provides subsidies to farmers to enable them to sell their

goods competitively on the world market. The end of

national passports has given millions of Europeans

greater flexibility in travel. The EU has been less suc-

cessful in setting common foreign policy goals, primarily

because individual nations still see foreign policy as a

national priority and are reluctant to give up this power

to a single overriding institution.

Toward a United Europe At the beginning of the

twenty-first century, the EU established a new goal: to

incorporate into the union the states of eastern and

southeastern Europe. Many of these states were consid-

erably poorer than the current members, which raised the

possibility that adding these nations might weaken the

EU itself. To lessen that danger, EU members established a

set of qualifications requiring applicants to demonstrate

their commitment both to market capitalism and to de-

mocracy and to exhibit respect for minorities and human

rights as well as for the rule of law. In May 2004, the EU

took the plunge and added ten new members: Cyprus, the

Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania,

Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia, thereby enlarging

the population of the EU to 455 million people. In

January 2007, the EU expanded again as Bulgaria and

Romania joined the union (see Map 28.1).

Emergence of the Superpower:

The United States

Q

Focus Question: What political, social, and economic

changes has the United States experienced since 1945?

At the end of World War II, the United States emerged as

one of the world’s two superpowers. As its Cold War

confrontation with the Soviet Union intensified, the

United States directed much of its energy toward com-

bating the spread of communism throughout the world.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union at the beginning of

the 1990s, the United States became the world’s foremost

military power.

American Politics and Society

Through the Vietnam Era

Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal of the 1930s initiated a

basic transformation of American society that continued

between 1945 and 1970. It included a dramatic increase in

the role and power of the federal government, the rise of

organized labor as a significant force in the economy and

politics, a commitment to the welfar e state, and a grudging

acceptance of minority problems. The New Deal in

American politics was bolstered by the election of

Democratic presidents---Harry Truman in 1948, John F.

K ennedy in 1960, and L yndon B. Johnson in 1964. Even the

election of a R epublican president, Dwight D. Eisenhower,

in 1952 and 1956 did not significantly alter the funda-

mental direction of the New Deal.

The economic boom after World War II fueled

confidence in the American way of life. A shortage of

consumer goods during the war left Americans with both

surplus income and the desire to purchase these goods

after the war. Then, too, the growing influence of orga-

nized labor enabled more and more workers to get the

wage increases that spurred the growth of the domestic

market. Between 1945 and 1973, real wages grew an av-

erage of 3 percent a year, the most prolonged advance in

U.S. history.

Starting in the 1960s, however, problems that had been

glossed over earlier came to the fore. The decade began on

a youthful and optimistic note when John F. Kennedy

EMERGENCE OF THE SUPERPOWER:THE UNITED STATES 703

(1917--1963), at age forty-three, became the youngest

elected president in the histor y of the United States and

the first born in the twentieth century. His own ad-

ministration, cut short by an assassin’s bullet on

November 22, 1963, focused primarily on foreign affairs.

Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson (1908--1973),

who won a new term as president in a landslide in 1964,

used his stunning mandate to pursue the growth of the

welfare state, first begun in the New Deal. Johnson’s

programs included health care for the elderly and the

War on Poverty, to be fought with food stamps and the

Job Corps.

Johnson’s other domestic passion was achieving equal

rights for black Americans. In August 1963, the eloquent

Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. (1929--1968) led the

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom to dramatize

blacks’ desire for freedom. This march and King’s

impassioned plea for racial equality had an electrifying

effect on the American people. President Johnson pur-

sued the cause of civil rights. As a result of his initiative,

Congress enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which

created the machinery to end segregation and discrimi-

nation in the workplace and all public accommodations.

The Voting Rights Act the following year eliminated ob-

stacles to black participation in elections in southern

states. But laws alone could not guarantee the Great

Society that Johnson envisioned, and soon the adminis-

tration faced bitter social unrest.

In the North and the West, blacks had had voting

rights for many years, but local patterns of segregation

resulted in considerably higher unemployment rates for

blacks (and Hispanics) than for whites and left blacks

segregated in huge urban ghettos. In the summer of 1965,

race riots erupted in the Watts district of Los Angeles that

S

PAIN

PO

OR

R

R

TU

U

UG

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

AL

L

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

U

Lis

sb

o

on

Mad

ri

d

UN

N

UN

UN

UN

UNI

UN

N

UN

UN

N

N

N

UN

UN

N

N

U

N

UN

N

N

N

N

TED

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

D

UN

N

N

UN

UN

UN

UN

UN

N

N

N

UN

N

N

UN

UN

N

N

N

KIN

K

K

K

K

K

KIN

K

K

KIN

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

GDO

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

KIN

K

K

K

K

K

KIN

KIN

K

KIN

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

IRE

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

L

L

L

LAN

LA

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

D

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

L

L

L

LA

L

LA

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

L

FRANCE

SWIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

W

W

W

WIT

ZERL

ERL

RL

RL

ERL

ERL

ERL

ERL

R

ERL

ERL

E

R

R

AN

AN

AN

A

AN

AND

AN

AN

N

AN

A

A

N

N

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

WIT

W

WIT

W

W

W

WIT

W

W

ERL

ERL

ERL

RL

ERL

ERL

ERL

ERL

ERL

ERL

ERL

ERL

R

ERL

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

A

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

A

N

N

ITA

LY

AL

AL

AL

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

A

A

A

AUS

A

AU

A

AU

A

A

A

A

AU

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

AU

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

TRI

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

AU

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

AU

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

SLOV

OV

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

OV

OV

OV

OV

OV

V

V

O

V

V

ENIA

ANIA

A

ENIA

ENIA

N

NIA

A

A

A

EN

NIA

E

E

N

E

E

N

E

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

ENIA

ENIA

NIA

NIA

NIA

N

N

NIA

N

N

N

EN

N

A

N

N

N

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

OV

OV

OV

OV

OV

OV

OV

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

Ljub

L

jub

Ljub

Ljub

Ljub

Lju

Ljub

Ljub

L

L

L

Lj

Lj

u

ub

u

b

u

ljan

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

a

a

Ljub

L

Ljub

Ljub

Ljub

Ljub

Ljub

Lju

L

Ljub

Lj

Ljub

L

Ljub

Ljub

L

Lj

L

L

Lj

Lj

jub

u

ub

u

ub

u

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

a

a

a

a

a

a

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

j

Rome

me

me

me

m

me

me

me

e

me

me

me

me

me

me

me

e

d

Lond

d

Lond

d

on

on

on

o

o

o

on

o

o

o

n

d

d

d

d

d

d

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

o

D

Dubl

in

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

ubl

in

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

nn

D

D

DD

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

Bern

Be

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

Be

Be

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

V

V

Vien

V

V

V

na

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

Vien

na

ienna

Vienna

LIECHTENSTEIN

C

L

C

C

NST

L

L

C

C

C

C

ENST

ENST

LUXE

MBOU

RG

G

BELG

BELG

ELG

BELG

BELG

BELG

BELG

ELG

G

L

B

IUM

LG

LG

L

LG

LG

G

G

L

IUM

M

BELG

BELG

BELG

BELG

BELG

BELG

BELG

LG

L

LG

G

LG

LG

LG

G

G

B

B

B

NET

NETH

TH

E

ERLA

RLA

RLA

RLA

RLA

RLA

LA

LA

LA

NDS

NDS

NDS

DS

NDS

NDS

NDS

NDS

NDS

NDS

NDS

N

RLA

LA

RLA

RLA

LA

LA

LA

RLA

NDS

NDS

NDS

NDS

NDS

NDS

NDS

DS

ER

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

DEN

EN

EN

E

EN

E

E

E

EN

E

E

N

E

E

E

E

EN

EN

EN

EN

EN

EN

E

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

E

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

R

MAR

MAR

MAR

MAR

M

R

AR

MA

MA

M

M

AR

M

M

M

M

M

M

R

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

E

EN

EN

E

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

E

N

N

N

N

N

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

N

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

EN

E

E

E

E

E

E

EN

E

E

E

E

E

EN

E

E

EN

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

MA

MA

MAMA

MA

MA

MA

MA

MA

MA

MA

M

A

M

A

A

A

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

AR

AR

R

R

R

A

AR

A

AR

R

R

AR

A

ARAR

R

AR

R

A

A

R

R

K

K

K

K

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

K

GERMANY

Y

Y

Y

CZEC

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

H REPUBLIC

LIC

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

LI

NOR

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

WAY

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

S

WEDE

N

FINLAN

D

R

USSIA

ES

ES

EST

ES

EST

EST

E

ES

E

ES

ES

ES

S

S

ONI

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

ES

ES

EST

ES

ES

ES

ES

ES

S

E

E

E

LAT

VI

VIA

VIA

VI

VI

IA

IA

IA

I

IA

LAT

VI

V

VIA

IA

VI

VI

IA

VIA

I

I

IA

I

K

AZAKHSTAN

Prague

ague

Pra

ra

Pra

P

a

ri

s

A

Amst

st

st

st

st

st

t

st

s

e

e

erda

r

er

er

r

er

r

r

e

m

m

er

st

st

s

st

t

st

s

s

e

e

er

er

st

t

st

t

t

t

t

e

e

e

e

t

t

e

r

erer

e

er

e

er

er

er

er

Brussels

russe

Ber

er

er

erl

er

r

er

e

e

in

er

er

erer

er

r

r

er

r

e

e

Oslo

Oslo

OsloOslo

lo

Oslo

Oslo

Oslo

Os

Oslo

l

sl

Osl

Osl

o

o

O

O

o

o

Os

Os

Os

Os

Os

Os

Os

Os

s

O

O

slo

lo

lo

slo

slo

lo

lo

lo

o

o

o

o

o

o

Stockhol

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

m

Hels

H

H

H

H

He

H

H

H

He

H

H

H

H

H

H

inki

H

He

H

H

H

He

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

Tall

l

ll

l

l

ll

ll

ll

ll

l

i

nn

i

i

i

i

i

inn

n

inn

nn

n

n

n

nn

nn

n

nn

n

n

nn

n

n

n

n

nn

n

n

n

n

Tll

Tl

Tll

ll

l

l

ll

l

l

i

i

i

i

i

inn

in

R

R

R

Riga

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

C

C

Cope

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

nhag

nha

nh

hag

nhag

nha

nhag

hag

hag

nhag

h

nh

h

ha

h

h

hag

h

nhag

h

nhag

hag

h

en

en

en

en

en

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

nha

nha

nh

ha

nha

nha

nha

ha

ha

nha

ha

ha

nha

h

nh

h

h

nha

h

h

h

h

h

h

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

en

en

en

en

en

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

MO

O

OL

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

DOV

A

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

DO

P

O

LAND

SLOV

AKIA

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

IA

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

HUN

GAR

R

R

R

R

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

N

N

N

U

KR

A

INE

BELARU

S

LI

I

LIT

LI

L

L

L

L

L

T

I

LI

L

L

LI

LI

L

I

LI

L

LI

I

I

IT

I

I

I

T

T

HUA

NIA

A

LI

I

I

IT

LI

I

L

IT

L

I

I

I

IT

T

L

I

I

I

I

IT

I

T

LI

I

LI

LI

L

L

L

L

LI

L

LI

LI

LI

LI

LI

LI

L

LI

L

LI

I

I

LI

LI

L

L

L

I

Buda

pes

e

e

pe

est

e

e

e

e

pes

pepest

pes

pes

est

es

es

e

e

e

e

e

e

pe

Wars

a

aw

aw

aw

aw

a

aw

aw

aw

s

aw

a

a

a

aw

aw

a

aw

a

aw

w

Mi

ns

k

Vil

ln

l

l

l

l

V

V

ius

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

n

n

l

V

l

Brat

isla

va

rat

isla

Ki

ev

Chis

inau

u

a

au

u

u

a

u

a

Ch

au

au

au

au

u

u

a

RO

MANI

A

BUL

GAR

R

R

R

R

AR

AR

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

A

R

AR

R

R

R

R

R

AR

R

R

R

R

IA

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

AR

R

AR

R

AR

R

A

A

AR

AR

R

R

AR

R

R

R

A

R

AR

A

R

AR

A

A

A

A

AR

A

R

R

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

ALB

L

LB

LBA

LB

L

LB

B

LB

LB

LB

A

A

LB

A

A

A

A

N

NIA

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

LB

LB

LB

LB

LB

B

LB

LB

B

B

B

B

B

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

GRE

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

EC

CE

CE

CE

C

CE

C

CE

C

C

CE

C

C

CE

CE

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

CE

C

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

EC

C

CC

C

C

C

C

C

C

EC

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

TURKEY

GEO

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

RGIA

RGIA

G

G

ARM

ENI

A

RMENIA

N

EN

RM

JAN

AZERBA

IJ

J

J

I

J

AZE

ERBA

AZ

IJ

IJ

J

IJ

J

J

J

J

IJ

BOSN

B

IA

A

B

B

A

A

CROA

R

ROA

TIA

TIA

A

ROA

ROA

ROA

TIA

TIA

TIA

MACE

E

E

E

E

E

CE

C

ACE

E

E

E

AC

DONI

DONI

DON

N

DONI

NI

N

DONI

N

N

N

N

N

O

I

I

N

N

NI

DONI

I

D

D

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

DONI

DONI

DON

ON

DON

DONI

NI

NI

O

DO

ON

ONI

DONI

DON

N

N

N

O

N

O

DONI

DO

DONI

N

DON

NI

DONI

I

D

D

D

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

ACE

E

E

ACE

E

ACE

CE

CE

ACE

C

E

A

CE

C

SERB

IA

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

IR

AN

IRAQ

RA

SYR

IA

A

C

CYP

YP

YP

YP

YP

YP

YP

YP

YP

Y

YP

C

RU

RU

RU

RUS

RU

RU

RU

RU

U

RU

YP

YP

YP

YP

YP

YP

YP

YP

YP

P

RU

RU

RU

RU

RU

RU

RU

RU

RU

RU

A

n

k

ar

a

A

A

Athe

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

ns

n

n

ns

ns

s

ns

n

n

s

n

ns

ns

s

n

ns

ns

ns

ns

s

s

s

s

n

s

s

s

s

s

s

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

ns

ns

ns

n

ns

n

ns

ns

n

s

n

n

Tira

na

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

Belg

rad

d

de

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

rad

d

d

d

de

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

ad

d

d

de

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

ad

de

d

d

d

d

d

d

ad

d

ad

d

de

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

d

Sofia

Buch

ares

e

es

es

es

e

es

es

e

e

es

es

es

e

e

e

t

t

t

t

ha

h

a

h

a

es

es

es

es

es

es

es

es

es

e

e

es

es

es

e

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

Tbilisi

bi

Baku

Ba

B

B

Ba

B

Ba

Ba

Ba

B

Ba

B

Ba

Yerevan

an

S

S

Sara

ara

S

Sa

S

Sa

S

Sa

S

S

S

S

S

S

jevo

j

ra

ra

j

j

S

Sa

Sa

Sa

Sa

Sa

S

Sa

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

O

Skop

Skop

S

Skop

Sk

Sk

S

Sk

Sk

S

p

je

je

Skop

Skop

S

Skop

p

p

p

p

je

je

S

Sk

Sk

S

Sk

Sk

Sk

Zagr

Zag

Zagr

Zagr

Zag

Z

Z

Za

Z

Z

Zag

Zagr

agr

a

a

ag

eb

eb

b

b

b

b

b

b

eb

e

b

e

e

Zagr

gr

Zagr

Zagr

Zagr

Z

Zag

Zagr

Zagr

Za

Zagr

Z

Zag

Zagr

agr

agr

agr

agr

g

g

eb

eb

eb

b

b

b

b

b

b

eb

eb

eb

b

eb

b

b

b

e

e

e

e

e

b

b

b

b

e

eb

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

eb

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

MONT

ENE

ENE

NE

ENEG

NEG

NEG

ENE

EN

ENE

ENE

ENE

ENE

ENE

G

N

N

N

E

RO

O

O

O

O

NEG

NEG

NEG

N

G

N

G

O

ENE

ENE

ENE

ENE

ENE

ENE

ENE

ENE

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

T

EN

E

E

E

EN

E

A

tla

n

tic

O

cea

n

N

orth

S

e

a

B

a

B

l

t

i

c

S

e

S

a

Black

S

e

a

Caspian Sea

u

A

rctic

O

cea

n

N

orwe

g

ian

S

ea

EE

E

E

b

b

b

b

r

r

o

o

R

.

D

n

i

e

p

p

e

e

e

e

e

ee

e

e

ee

e

e

r

R

.

V

o

V

V

l

g

a

R

.

S

e

i

n

i

e

n

R

.

R

R

R

R

h

i

n

e

n

n

D

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

u

b

b

b

b

e

e

e

e

e

R

R

R

.

.

R.

P

P

o

R

R

.

.

D

o

D

D

n

R

.

M

e

d

i

t

e

r

r

a

n

e

a

n

S

e

a

0

250 500 Mile

s

0

2

250

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

5

500

750 Kilometers

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

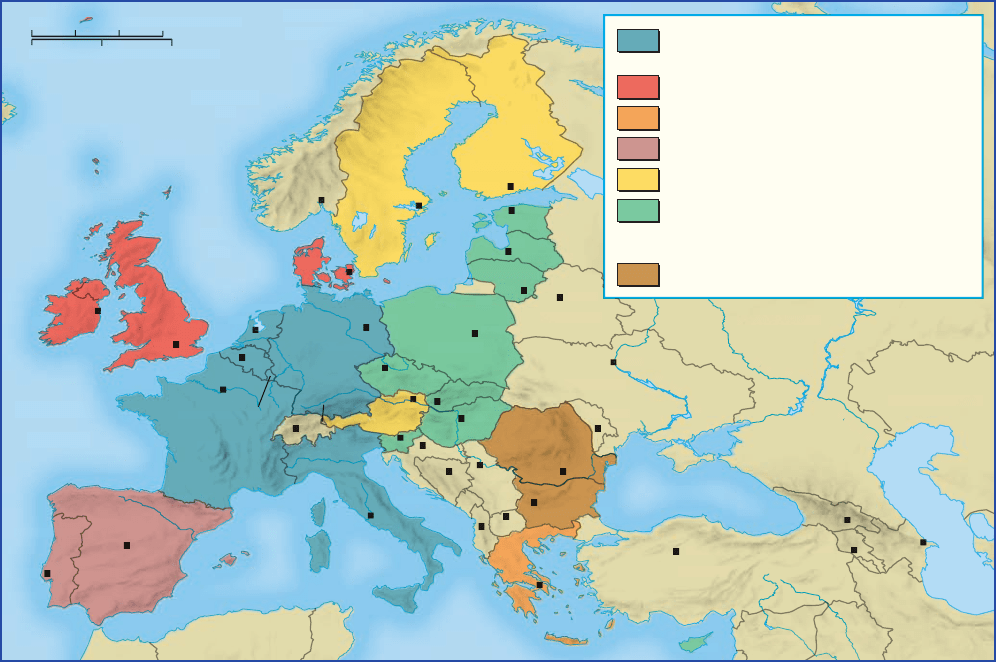

1967: France, West Germany, Belgium,

Netherlands, Luxembourg, Italy

1973: Great Britain, Ireland, Denmark

1981: Greece

1986: Spain, Portugal

1995: Austria, Finland, Sweden

2004: Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary,

Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland,

Slovakia, Slovenia, and Cyprus

2007: Bulgaria, Romania

MAP 28.1 Europe an Union, 2009. Beginning in 1957 as the European Economic

Community, also known as the Common Mar ket, the union of European states seeking to

integrate their economies has gradually grown from six members to twenty-seven. By 2002, the

European Union had achieved two major goals—the creation of a single internal market and a

common currency—although it has been less successful at working toward common political

and foreign policy goals.

Q

What additional nations do you think will eventually join the European Union?

704 CHAPTER 28 EUROPE AND THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE SINCE 1945

led to thirty-four deaths and the destruction of over one

thousand buildings. After King was assassinated in 1968,

more than one hundred cities erupted in rioting, in-

cluding Washington, D.C., the nation’s capital. The riots

led to a ‘‘white backlash’’ and a severe racial division of

America.

Antiwar protests also divided the American people

after President Johnson committed American troops to a

costly war in Vietnam (see Chapter 26). The killing of

four student protesters at Kent State University in 1970 by

the Ohio National Guard shocked both activists and or-

dinary Americans, and thereafter the vehemence of the

antiwar movement began to subside. But the combina-

tion of antiwar demonstrations and riots in the cities

caused many people to call for ‘‘law and order,’’ an appeal

used by Richard Nixon (1913--1994), the Republican

presidential candidate in 1968. With Nixon’s election in

1968, a shift to the right in American politics had begun.

The Shift Rightward After 1973

Nix on ev entually ended American involv ement in Vietnam

by gradually withdrawing American troops. P olitically, he

pursued a ‘‘southern strategy ,’’ carefully calculating that

‘‘law and order’’ issues would appeal to southern whites.

The Republican strategy, however, also gained support

among white Democrats in northern cities, where court-

mandated busing to achieve racial integration had pro-

voked a white backlash.

As president, Nixon was paranoid about conspiracies

and resorted to subversive methods of gaining political

intelligence on his political opponents. Nixon’s zeal led to

the Watergate scandal---a botched attempt to bug the

Democratic National Headquarters and the ensuing cov-

erup. Although Nixon repeatedly denied involvement in

the affair, secret tapes he made of his own conversations in

the White House revealed otherwise. On August 9, 1974,

Nixon resigned in disgrace, an act that saved him from

almost certain impeachment and conviction.

After Watergate, American domestic politics focused

on economic issues. Gerald Ford (1913--2006) became

president when Nixon resigned, only to lose in the 1976

election to the former governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter

(b. 1924). By 1980, the Carter administration faced two

devastating problems. High inflation and a decline in

average weekly earnings were causing a perceptible drop in

American living standards. At the same time, a crisis

abroad had erupted when fifty-three Americans were taken

hostage by the Iranian government of Ayatollah Khomeini

and held for nearly fifteen months (see Chapter 29). Car-

ter’s inability to gain the release of the American hostages

led to perceptions at home that he was a weak president.

His overwhelming loss to Ronald Reagan (1911--2004) in

the election of 1980 brought forward the chief exponent of

right-wing R epublican policies.

The Reagan Rev olution, as it has been called, sent U.S.

policy in a number of new directions. Reversing decades of

changes, Reagan cut back on the welfare state by decreasing

spending on food stamps, school lunch programs, and job

programs. At the same time, his administration fostered

the largest peacetime military buildup in American history .

Total federal spending rose from $631 billion in 1981 to

more than $1 trillion by 1986. The administration’s

spending policies produced record government deficits,

which loomed as an obstacle to long-term growth. In the

1970s, the total national debt was $420 billion; under

Reagan it reached three times that amount.

The inability of Reagan’s successor, George H. W.

Bush (b. 1924), to deal with the deficit problem, coupled

with an economic downturn, led to the election of a

Democrat, Bill Clinton (b. 1946), in November 1992. The

new president was a southerner who claimed to be a new

Democrat---one who favored a number of the Republican

policies of the 1980s. This was a clear indication that the

rightward drift in American politics was by no means

ended by this Democratic victory.

President Clinton’s political fortunes were aided

considerably by a lengthy economic revival. A steady re-

duction in the annual government budget deficit

strengthened confidence in the performance of the na-

tional economy. Much of Clinton’s second term, however,

was overshadowed by charges of misconduct stemming

from the president’s affair with a White House intern.

After a bitter partisan struggle, the U.S. Senate acquitted

the president on two articles of impeachment brought by

the House of Representatives. But Clinton’s problems

helped the Republican candidate, George W. Bush

(b. 1946), to win the presidential election in 2000.

The first four years of Bush’s administration were

largely occupied with the war on terrorism and the U.S.-

led war on Iraq (see Chapter 29). The Department of

Homeland Security was established after the 2001 terrorist

assaults to help protect the country from future terrorist

acts. At the same time, Bush pushed tax cuts through

Congress that mainly favored the wealthy and helped

produce record deficits reminiscent of the Reagan years.

Environmentalists were especially disturbed by the Bush

administration’s efforts to weaken environmental laws and

regulations to benefit American corporations. During his

second term, Bush’s popularity plummeted drastically as

discontent grew over the Iraq War, financial corruption in

the Republican P arty, and the administration ’s poor

handling of relief efforts after Hurricane Katrina. The

many failures of the Bush administration led to the lowest

approval ratings for a modern president and opened the

door for a dramatic change in American politics.

EMERGENCE OF THE SUPERPOWER:THE UNITED STATES 705