Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 1: To 1800

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Greek fire, a petroleum-based compound containing quick-

lime and sulfur , destroyed the Muslim fleet, thereby saving

the empir e and indirectly Christian E urope, sinc e the fall of

Constantinople would have opened the door to an Arab

in vasion of eastern E urope. The Byzantine Empire and Islam

now established an uneasy frontier in southern Asia Minor .

Succession Problems

Arab power also extended to the east, consolidating Is-

lamic rule in Mesopotamia and Persia, and northward

into Central Asia. But factional disputes continued to

plague the empire. Many Muslims of non-Arab extraction

resented the favoritism shown by local administrators to

Arabs. In some cases, resentment led to revolt, as in Iraq,

where Ali’s second son, Hussein, disputed the legitimacy

of the Umayyads and incited his supporters---to be known

in the future as Shi’ites (from the Arabic phrase shi’at Ali,

‘‘partisans of Ali’’)---to rise up against Umayyad rule in

680. Although Hussein’s forces were defeated and Hussein

himself died in the battle, a schism between Shi’ite and

Sunni (usually translated as ‘‘orthodox’’) Muslims had

been created that continues to this day.

Umayyad rule, always (in historian Arthur Gold-

schmidt’s words) ‘‘more political than pious,’’ created

resentment, not only in Mesopotamia, but also in North

Africa, where Berber resistance continued, especially in

the mountainous areas south of the coastal plains. Ac-

cording to critics, the Umayyads may have contributed to

their own demise by their decadent behavior. One caliph

allegedly swam in a pool of wine and then imbibed

enough of the contents to lower the level significantly.

Finally, in 750, a revolt led by Abu al-Abbas, a descendant

of Muhammad’s uncle, led to the overthrow of the

Umayyads and the establishment of the Abbasid dynasty

(750--1258) in what is now Iraq.

The Abbasids

The Abbasid caliphs brought political, economic, and

cultural change to the world of Islam. While seeking to

implant their own version of religious orthodoxy, they

tried to break down the distinctions between Arab and

non-Arab Muslims. All Muslims were now allowed to

hold both civil and military offices. This change helped

open Islamic culture to the influences of the occupied

civilizations. Many Arabs now began to intermarry with

the peoples they had conquered. In many parts of the

Islamic world, notably North Africa and the eastern

Mediterranean, most Muslim converts began to consider

themselves Arabs. In 762, the Abbasids built a new capital

city at Baghdad, on the Tigris River far to the east of the

Umayyad capital at Damascus. The new capital was

strategically positioned to take advantage of river traffic

to the Persian Gulf and also lay astride the caravan route

from the Mediterranean to Central Asia. The move

eastward allowed Persian influence to come to the fore,

encouraging a new cultural orientation. Under the Ab-

basids, judges, merchants, and government officials,

rather than warriors, were viewed as the ideal citizens.

Abbasid Rule The new Abbasid caliphate experienced a

period of splendid rule well into the ninth century. Best

known of the caliphs of the time was Harun al-Rashid

(786--809), or Harun ‘‘the Upright,’’ whose reign is often

described as the golden age of the Abbasid caliphate. His

son al-Ma’mun (813--833) was a patron of learning who

founded an astronomical observatory and established a

foundation for undertaking translations of Classical

Greek works. This was also a period of growing economic

prosperity. The Arabs had conquered many of the richest

provinces of the Roman Empire and now controlled the

routes to the east (see Map 7.3). Baghdad became the

center of an enormous commercial market that extended

into Europe, Central Asia, and Africa, greatly adding to

the wealth of the Islamic world and promoting an ex-

change of culture, ideas, and technology from one end of

the known world to the other. Paper was introduced from

China and eventually passed on to North Africa and

Europe. Crops from India and Southeast Asia such as rice,

sugar, sorghum, and cotton moved toward the west, while

glass, wine, and indigo dye were introduced into China.

Under the Abbasids, the caliphs became more regal.

More temporal than spiritual leaders, described by such

august phrases as the ‘‘caliph of God,’’ they ruled by au-

tocratic means, hardly distinguishable from the kings and

emperors in neighboring states. A thirteenth-century

Chinese author, who compiled a world geography based

on accounts by Chinese travelers, left the following de-

scription of one of the later caliphs:

The king wears a turban of silk brocade and foreign cotton

stuff [buckram]. On each new moon and full moon he puts

on an eight-sided flat-topped headdress of pure gold, set

with the most precious jewels in the world. His robe is of

silk brocade and is bound around him with a jade girdle.

On his feet he wears golden shoes. ... The king’s throne is

set with pearls and precious stones, and the steps of the

throne are covered with pure gold.

3

As the caliph took on more of the trappings of a

hereditary autocrat, the bureaucracy assisting him in

administering the expanding empire grew more complex

as well. The caliph was advised by a council (called a

diwan) headed by a prime minister, known as a vizier

(wazir). The caliph did not attend meetings of the diwan

in the normal manner but sat behind a screen and then

164 CHAPTER 7 FERMENT IN THE MIDDLE EAST: THE RISE OF ISLAM

communicated his divine will to the vizier. Some histo-

rians have ascribed the change in the caliphate to Persian

influence, which permeated the empire after the capital

was moved to Baghdad. Persian influence was indeed

strong (the mother of the caliph al-Ma’mun, for example,

was a Persian), but more likely, the increase in pomp and

circumstance was a natural consequence of the growing

power and prosperity of the empire.

Instability and Division Nevertheless, an element of

instability lurked beneath the surface. The lack of spiritual

authority may have weakened the caliphate in competi-

tion with its potential rivals, and disputes over the suc-

cession were common. At Harun’s death, the rivalry

between his two sons, Amin and al-Ma’mun, led to civil

war and the destruction of Baghdad. As described by the

tenth-century Muslim historian al-Mas’udi, ‘‘Mansions

were destroyed, most remarkable monuments obliterated;

prices soared. ... Brother tur ned his sword against brother,

son against father, as some fought for Amin, others for

Ma’mun. Houses and palaces fueled the flames; property

was put to the sack.’’

4

Wealth contributed to financial corruption. By awarding

important positions to court favorites, the Abbasid caliphs

began to undermine the foundations of their own power

and eventually became mere figureheads. Under Harun al-

Rashid, members of his Hashemite clan received large

pensions from the state treasury, and his wife, Zubaida,

reported ly spen t hug e sum s shopping while on a pil -

grimage to Mecca. One powerful family, the Barmakids,

amassed vast wealth and power until Harun al-Rashid

eliminated the entire clan in a fit of jealousy.

The life of luxury enjoyed by the caliph and other

political and economic elites in Baghdad seemingly un-

dermined the stern fiber of Arab society as well as the

strict moral code of Islam. Strictures against sexual pro-

miscuity were widely ignored, and caliphs were rumored

to maintain thousands of concubines in their harems.

Divorce was common, homosexuality was widely prac-

ticed, and alcohol was consumed in public despite Islamic

law’s prohibition against imbibing spirits.

The process of disintegration was accelerated by

changes that were taking place within the armed forces

and the bureaucracy of the empire. Given the shortage of

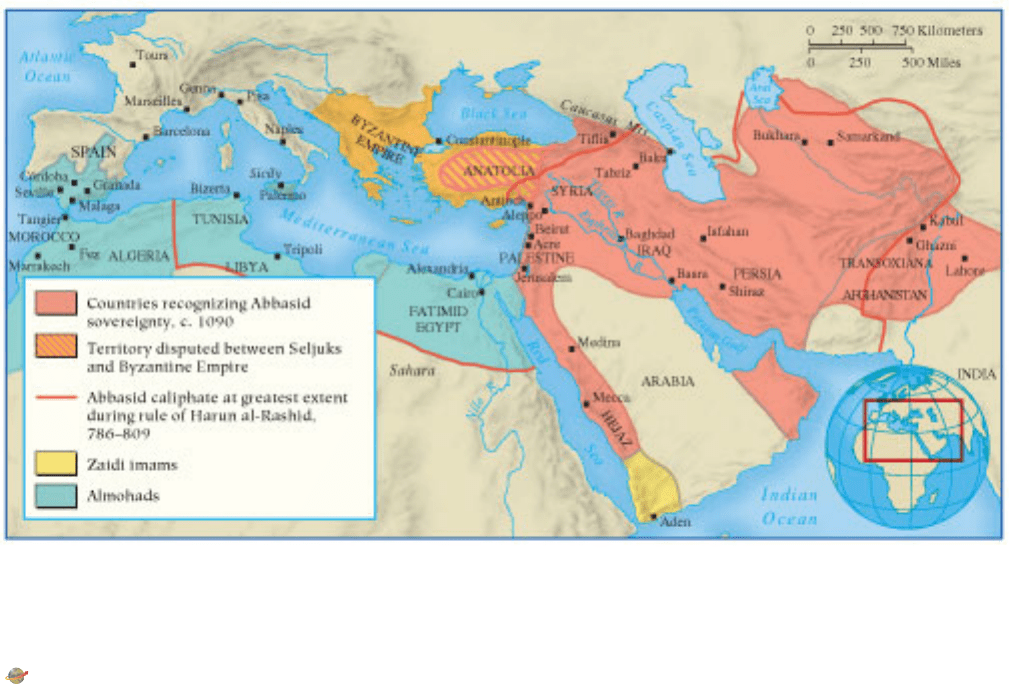

MAP 7.3 The Abbasid Caliphate at the Height of Its Power. The Abbasids arose in the

eighth century as the defenders of the Muslim faith and establ ished their capital at Baghdad.

With its prowess as a trading state, the caliphate was the most powerful and extensive state in

the region for several centuries.

Q

What were the major urban centers under the influence of I slam, as shown on this map?

Vi ew an animated version of this map or related maps at www .cengage.com/history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

THE ARAB EMPIRE AND ITS SUCCESSORS 165

qualified Arabs for key positions in the army and the

administration, the caliphate began to recruit officials

from among the non-Arab peoples in the empire, such as

Persians and Turks from Central Asia. These people

gradually became a dominant force in the army and

administration.

Pro vincial rulers also began to break awa y from central

control and establish their own independent dynasties.

Already in the eighth century , a separate caliphate had been

established in Spain (see ‘‘Andalusia: A M uslim Outpost in

Eur ope’’ later in the chapter). En vironmental problems

added to the regime’s difficulties. The Tigris and E uphrates

river system, lifeblood of Mesopotamia for three millennia,

was beginning to silt up. Bureaucratic inertia now made

things worse, as many of the country’ s canals became vi r -

tually unusable, leading to widespread food shortages.

The fragmentation of the Islamic empire accelerated

in the tenth century. Morocco became independent, and

in 973, a new Shi’ite dynasty under the Fatimids was

established in Egypt with its capital at Cairo. With in-

creasing disarray in the empire, the Islamic world was

held together only by the common commitment to the

Qur’an and the use of the Arabic language as the pre-

vailing means of communication.

The Seljuk Turks

In the eleventh century, the Abbasid caliphate faced yet

another serious threat in the form of the Seljuk Turks.

The Seljuk Turks were a nomadic people from Central

Asia who had converted to Islam and flourished as mil-

itary mercenaries for the Abbasid caliphate, where they

were known for their ability as mounted archers. Moving

gradually into Iran and Armenia as the Abbasids weak-

ened, the Seljuk Turks grew in number until by the

eleventh century, they were able to occupy the eastern

provinces of the Abbasid empire. In 1055, a Turkish

leader captured Baghdad and assumed command of the

empire with the title of sultan (‘‘holder of power’’). While

the Abbasid caliph remained the chief representative of

Sunni religious authority, the real military and political

power of the state was in the hands of the Seljuk Turks.

The latter did not establish their headquarters in Bagh-

dad, which now entered a period of decline. As the his-

torian Khatib Baghdadi described:

There is no city in the world equal to Baghdad in the abun-

dance of its riches, the importance of its business, the num-

ber of its scholars and important people, the distinctions of

its leaders and its common people, the extent of its palaces,

inhabitants, streets, avenues, alleys, mosques, baths, docks

and caravansaries, the purity of its air, the sweetness of its

water, the freshness of its dew and its shade, the temperate-

ness of its summer and winter, the healthfulness of its spring

and fall, and its great swarming crowds. The buildings and

the inhabitants were most numerous during the time of

Harun al-Rashid, when the city and its surrounding areas

were full of cooled rooms, thriving places, fertile pastures,

rich watering-places for ships. Then the riots began, an unin-

terrupted series of misfortunes befell the inhabitants, its

flourishing conditions came to ruin to such extent that,

before our time and the century preceding ours, it found

itself, because of the perturbation and the decadence it was

experiencing, in complete opposition to all capitals and in

contradiction to all inhabited countries.

5

Baghdad would revive, but it would no longer be the ‘‘gift

of God’’ of Harun al-Rashid.

By the last quarter of the eleventh century, the Sel-

juks were exerting military pressure on Egypt and the

Byzantine Empire. In 1071, when the Byzantines fool-

ishly challenged the Turks, their army was routed at

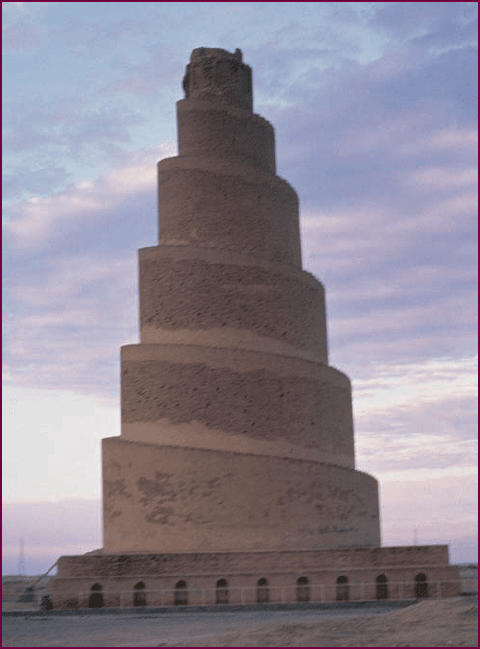

The Great Mosque of Samarra. The ninth-century mosque of

Samarra, located north of Baghdad in present-day Iraq, was for centuries

the largest mosque in the Islamic world. Rising from the center of the city

of Samarra, the capital of the Abbasids for over half a century and one of

the largest medieval cities of its time, the imposing tower shown here is

156 feet in height. Its circular ramp may have inspired medieval artists in

Europe as they imagined the ancient cultures of Mesopotamia. Although

the mosque is in ruins today, its spiral tower still signals the presence of

Islam to the faithful across the broad valley of the Tigris and Euphrates

rivers.

c

The Bridgeman Art Library

166 CHAPTER 7 FERMENT IN THE MIDDLE EAST: THE RISE OF ISLAM

Manzikert, near Lake Van in eastern Turkey, and the

victors took over most of the Anatolian peninsula (see

Map 7.4). In dire straits, the Byzantine Empire turned to

the west for help, setting in motion the papal pleas that

led to the Crusades (see the next section).

In Europe, and undoubtedly within the Muslim

world itself, the arrival of the Turks was regarded as a

disaster. T he Turks were viewed as bar barians who

destroyed civ ilizations and oppressed populations. In

fact, in many respects, Turkish rule in the Middle East

was probably beneficial. Converted to Islam, the

Turkish rulers temporarily brought an end to the fra-

ternal squabbles between Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims

while supporting the Sunnites. They put their energies

into revitalizing Islamic law and institutions and pro-

vided much-needed political stability to the empire,

which helped restore its former prosperity. Under Sel-

juk rule, Muslims began to organize themselves into

autonomous brotherhoods, whose relatively tolerant

practices characterized Islamic religious attitudes until

the end of the nineteenth century, when increased

competition with Europe led to confrontation w ith the

West.

Seljuk political domination over the old Abbasid

Empire, however, provoked resentment on the part of

many Persian Shi’ites, who viewed the Turks as usurping

foreigners who had betrayed the true faith of Islam.

Among the regime’s most feared enemies was Hasan al-

Sabahh, a Cairo-trained Persian who formed a rebel

group, popularly known as ‘‘assassins’’ (guardians), who

for several decades terrorized government officials and

other leading political and religious figures from their

base in the mountains south of the Caspian Sea. Like their

modern-day equivalents in the terrorist organization

known as al-Qaeda, Sabahh’s followers were highly mo-

tivated and were adept at infiltrating the enemy’s camp in

order to carry out their clandestine activities. The orga-

nization was finally eliminated by the invading Mongols

in the thirteenth century.

The Crusades

Just before the end of the eleventh century, the Byzantine

emperor Alexius I desperately called for assistance from

other Christian states in Europe to protect his empire

against the invading Seljuk Turks. As part of his appeal,

he said that the Muslims were desecrating Christian

shrines in the Holy Land and molesting Christian pil-

grims en route to the shrines. In actuality, the Muslims

had never threatened the shrines or cut off Christian

access to them. But tension between Christendom and

Islam was on the rise, and the Byzantine emperor’s appeal

received a ready response in Europe. Beginning in 1096

and continuing into the thirteenth century, a series of

Christian incursions on Islamic territories known as the

Crusades brought the Holy Land and adjacent areas on

the Mediterranean coast from Antioch to the Sinai pen-

insula under Christian rule (see Chapter 12). In 1099, the

armies of the First Crusade succeeded in capturing

Jerusalem after a long siege (see the box on p. 168).

At first, Muslim rulers in the area were taken aback

by the invading crusaders, whose armored cavalry pre-

sented a new challenge to local warriors, and their re-

sponse was ineffectual. The Seljuk Turks by that time were

preoccupied with events taking place farther to the east

and took no action themselves. But in 1169, Sunni

Muslims under the leadership of Saladin (Salah al-Din),

vizier to the last Fatimid caliph, brought an end to the

Fatimid dynasty. Proclaiming himself sultan, Saladin

succeeded in establishing his control over both Egypt and

Syria, thereby confronting the Christian states in the area

with united Muslim power on two fronts. In 1187,

Saladin’s army invaded the kingdom of Jerusalem and

destroyed the Christian forces concentrated there. Further

operations reduced Christian occupation in the area to a

handful of fortresses along the northern coast. Unlike the

M

e

d

i

t

e

r

r

a

n

e

a

n

S

e

a

Aeg

ean

Se

a

Sea

Sea

of

of

Mar

M

mar

ar

a

a

f

B

lack

S

ea

Dar

Dar

dan

dan

dan

ell

el

l

es

s

es

ANATOL

IA

ABBASID

AS

EMPIRE

RE

Con

Co

Co

Co

C

Co

C

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

C

Co

Co

C

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

o

C

C

sta

nti

nople

Co

Co

Co

Co

C

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

C

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

Co

sta

B

u

r

sa

Bosporus

Tre

Tre

e

T

re

e

Tre

Tre

T

Tre

Tre

Tre

Tre

T

T

re

T

Tre

Tre

Tre

r

Tre

e

biz

biz

bi

bi

b

iz

bi

bi

biz

b

bi

i

bi

bi

b

b

bi

bi

b

bi

bi

i

i

i

ond

ond

nd

d

nd

d

d

nd

d

nd

d

d

d

d

d

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

b

bi

bi

bi

bi

bi

bi

bi

bi

b

b

i

bi

bi

bi

i

bi

b

i

i

d

d

nd

d

nd

d

nd

d

nd

d

d

d

n

d

T

Tr

Tre

Tre

Tr

Tre

Tre

Tre

T

Tre

TreTre

T

r

Tre

r

Tr

e

Manzikert

Cre

Cre

Cre

te

te

Cyp

Cyp

Cyp

ru

rus

us

A

A

L

IA

A

OL

L

TO

O

AT

T

NA

A

A

A

AN

A

N

A

N

AT

TO

OL

L

IA

A

M

M

an

zi

ke

k

t

rt

AN

A

rt

ke

zik

an

Ma

0

0

200 Miles

0

300 Kilometers

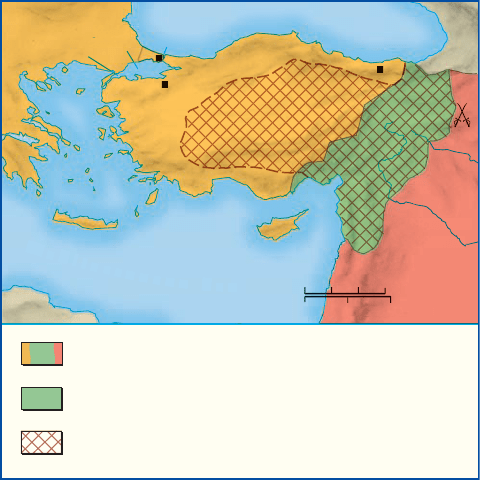

Frontier between the Byzantine and Abbasid

empires, c. 930

Areas of Anatolia occupied by the Seljuk Turks

in the early twelfth century

Areas of Anatolia occupied by the Abbasids in 1070

MAP 7.4 The Turkish Occupation of Anatolia. This map

shows the expansion of the Seljuk Turks into the Anatolian

peninsula in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Later, another

group of Turkic-speaking peoples, the Ottoman Turks, would

move into the area, establishing their capital at Bursa in 1335

and eventually at Constantinople in 1453.

Q

What role did the expansion of the Seljuk Turks pla y in

the origin of the Crusades?

THE ARAB EMPIRE AND ITS SUCCESSORS 167

Christians, however, Saladin did not permit a massacre of

the civilian population and even tolerated the continua-

tion of Christian religious services in conquered territo-

ries. For a time, Christian occupation forces even carried

on a lively trade relationship with Muslim communities

in the region.

The Christians returned for another try a few years

after the fall of Jerusalem, but the campaign succeeded

only in securing some of the coastal cities. Although the

Christians would retain a toehold on the coast for much

of the thirteenth century (Acre, their last stronghold, fell

to the Muslims in 1291), they were no longer a signifi-

cant force in Middle Eastern affairs. In retrospect, the

Crusades had only minimal importance in the history of

the Middle East, although they may have served to unite

the forces of Islam against the foreign invaders, thus

creating a residue of distrust toward Christians that

continues to resonate through the Islamic world today

(see the box above). Far more important in their impact

were the Mongols, a pastoral people who swept out of

the Gobi Desert in the early thirteenth century to seize

control over much of the known world (see Chapter 10).

Beginning with the advances of Genghis Khan in

northern China, Mongol armies later spread across

Central Asia, and in 1258, under the leadership of Hu-

legu, brother of the more famous Khubilai Khan, they

seized Persia and Mesopotamia, bringing an end to the

caliphate at Baghdad.

OPPOSING VIEWPOINTS

T

HE SIEGE OF JERUSALEM:CHRISTIAN AND MUSLIM PERSPECTIVES

During the First Crusade, Christian knights laid

siege to Jerusalem in June 1099. The first excerpt

is taken from an account by Fulcher of Chartres,

who accompanied the crusaders to the Holy Land.

The second selection is by a Muslim writer, Ibn al-Athir, whose

account of the First Crusade can be found in his history of the

Muslim world.

Fulcher of Chartres, Chronicle of the First Crusade

Then the Franks [the crusaders] entered the city magnificently at

the noonday hour on Friday, the day of the week when Christ

redeemed the whole world on the cross. With trumpets sounding

and with everything in an uproar, exclaiming: ‘‘Help, God!’’ they

vigorously pushed into the city, and straightway raised the banner

on the top of the wall. All the heathen, completely terrified, changed

their boldness to swift flight through the narrow streets of the quar-

ters. The more quickly they fled, the more quickly they put to flight.

Count Raymond and his men, who were bravely assailing the

city in another section, did not perceive this until they saw the Sara-

cens [Muslims] jumping from the top of the wall. Seeing this, they

joyfully ran to the city as quickly as they could, and helped the

others pursue and kill the wicked enemy.

Then some, both Arabs and Ethiopians, fled into the Tower

of David; others shut themselves in the Temple of the Lord and of

Solomon, where in the halls a very great attack was made on them.

Nowhere was there a place where the Saracens could escape

swordsmen.

On the top of Solomon’s Temple, to which they had climbed in

fleeing, many were shot to death with arrows and cast down head-

long from the roof. Within this Temple, about ten thousand were

beheaded. If you had been there, your feet would have been stained

up to the ankles with the blood of the slain. What more shall I tell?

Not one of them was allowed to live. They did not spare the women

and children.

Account of Ibn al-Athir

In fact Jerusalem was taken from the north on the morning of

Friday 22 Sha’ban 492/15 July 1099. The population was put to the

sword by the Franks, who pillaged the area for a week. A band of

Muslims barricaded themselves into the Oratory of David and

fought on for several days. They were granted their lives in return

for surrendering. The Franks honored their word, and the group left

by night for Ascalon. In the Masjid al-Aqsa the Franks slaughtered

more than 70,000 people, among them a large number of Imams

and Muslim scholars, devout and ascetic men who had left their

homelands to live lives of pious seclusion in the Holy Place. The

Franks stripped the Dome of the Rock of more than forty silver can-

delabra, each of them weighing 3,600 drams, and a great silver lamp

weighing forty-four Syrian pounds, as well as a hundred and fifty

smaller candelabra and more than twenty gold ones, and a great

deal more booty. Refugees from Syria reached Baghdad in Ramadan,

among them the qadi Abu sa’d al-Harawi. They told the Caliph’s

ministers a story that wrung their hearts and brought tears to their

eyes. On Friday they went to the Cathedral Mosque and begged for

help, weeping so that their hearers wept with them as they described

the sufferings of the Muslims in that Holy City: the men killed, the

women and children taken prisoner, the homes pillaged. Because of

the terrible hardships they had suffered, they were allowed to break

the fast.

Q

What happened to the inhabitants of Jerusalem when

the Christian knights captured the city? How do you explain the

extreme intolerance and brutality of the Christian knights?

How do these two accounts differ, and how are they similar?

168 CHAPTER 7 FERMENT IN THE MIDDLE EAST: THE RISE OF ISLAM

The Mongols

Unlike the Seljuk Turks, the Mongols were not Muslims,

and they found it difficult to adapt to the settled con-

ditions that they found in the major cities in the Middle

East. Their treatment of the local populatio n in conquer ed

territories was brutal (according to one historian, after

conquering a city, they wiped out not only entir e families

but also their household pets) and destructive to the

economy. Cities were razed to the ground, and dams and

other irrigation works were destroyed, reducing prosperous

agricultural societies to the point of mass starvation. The

Mongols advanced as far as the R ed Sea, but their attempt

to seize Egypt failed, in part because of the effective re-

sistance posed by the Mamluks (a Turkish military class

originally composed of slav es; sometimes written as

Mamelukes), who had recently overthrown the adminis-

tration set up by Saladin and seized power for themselves.

Eventually, the Mongol rulers in the Middle East

began to take on the coloration of the peoples they had

conquered. Mongol elites converted to Islam, Persian

influence became predominant at court, and the cities

began to be rebuilt. By the fourteenth century, the

Mongol empire began to split into separate kingdoms and

then to disintegrate. In the meantime, however, the old

Islamic empire originally established by the Arabs in the

seventh and eighth centuries had come to an end. The

new center of Islamic civilization was in Cairo, now about

to promote a renaissance in Muslim culture under the

sponsorship of the Mamluks.

To the north, another new force began to appear on

the horizon with the rise of the Ottoman Turks on the

Anatolian peninsula. In 1453, Sultan Mehmet II seized

Constantinople and brought an end to the Byzantine

Empire. Then the Ottomans began to turn their attention

to the rest of the Middle East (see Chapter 16).

Andalusia: A Muslim Outpost in Europe

After the decline of Baghdad, perhaps the brightest star in

the Muslim firmament was in Spain, where a member of

the Ummayad dynasty had managed to establish himself

after his family’s rule in the Middle East had been over-

thrown in 750. Abd al-Rathman escaped the carnage in

Damascus and made his way to Spain, where Muslim

power had recently replaced that of the Visigoths. By 756,

he had legitimized his authority in southern Spain---

known to the Arabs as al-Andaluz and to Europeans as

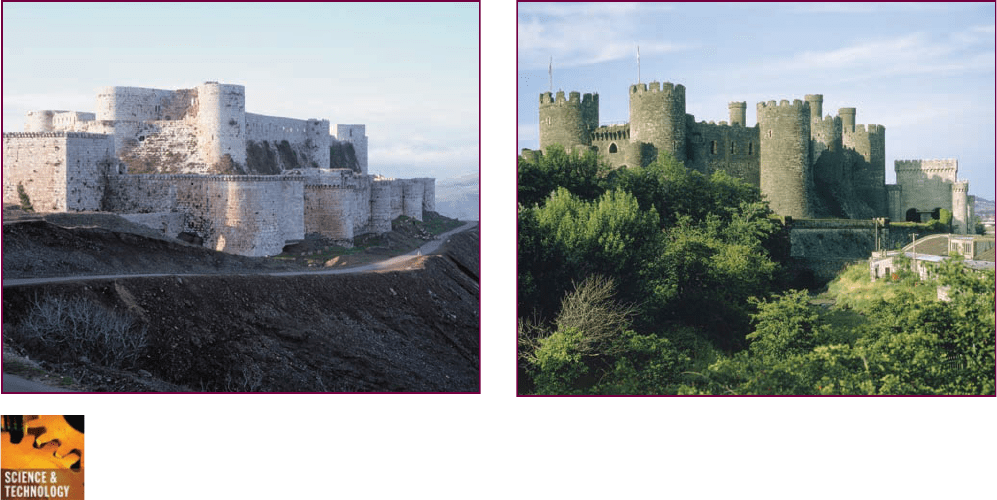

COMPARATIVE ILLUSTRATION

The Medi eval Castle. Beginning in the eighth century, Muslim rulers began to

erect fortified stone castles in the desert. So impressed were the crusaders by the

innovative defensive features they saw that th ey began to incorporate similar

features in their own European castles, which had previously been made of wood. In twelfth-

century Syria, the crusaders constructed the imposing citadel known as the Krak des

Chevaliers (Castle of the Knights) on the foundation of a Muslim fort (left photo). This new

model of a massive fortress of solid masonry spread to western Europe, as is evident in the

castle shown in the right photo, built in the late thirteenth century in Wales.

Q

What types of warfare wer e used to defend---and attack---castles such as these?

c

Michael Nicholson/CORBIS

c

Fridmar Damm/zefa/CORBIS

THE ARAB EMPIRE AND ITS SUCCESSORS 169

Andalusia---and took the title of emir (commander), with

his capital at C

ordoba. There he and his successors sought

to build a vibrant new center for Islamic culture in the

region. With the primacy of Baghdad now at an end,

Andalusian rulers established a new caliphate in 929.

Now that the seizure of Crete, Sardinia, Sicily, and the

Balearic Islands had turned the Mediterranean Sea into a

Muslim lake, Andalusia became part of a vast trade net-

work that stretched all the way from the Strait of Gibraltar

to the Red Sea and beyond. Valuable new products, in-

cluding cotton, sugar, olives, wheat, citrus, and the date

palm, were introduced to the Iberian peninsula.

Andalusia also flourished as an artistic and intellec-

tual center. The court gave active support to writers and

artists, creating a brilliant culture focused on the emer-

gence of three world-class cities---C

ordoba, Seville, and

Toledo. Intellectual leaders arrived in the area from all

parts of the Islamic world, bringing their knowledge of

medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy. With

the establishment of a paper factory near Valencia, the

means of disseminating such information dramatically

improved, and the libraries of Andalusia became the

wonder of their time (see ‘‘Philosophy and Science’’ later

in this chapter).

A major reason for the rise of Andalusia as a hub of

artistic and intellectual activity was the atmosphere of

tolerance in social relations fostered by the state. Al-

though Islam was firmly established as the official faith

and non-Muslims were encouraged to convert as a means

of furthering their careers, the policy of conviv

encia

(commingling) provided an environment for many

Christians and Jews to maintain their religious beliefs and

even obtain favors from the court.

A Time of Troubles Unfortunately, the primacy of

Andalusia as a cultural center was shor t-lived. By the

end of the tenth century, factionalism was beginning to

undermi ne the fo undations of the

emirate. In 1009, th e roya l p alace

at C

ordoba was to tally destroyed

in a c ivil war. Twenty years later,

the caliphate itself disappeared as

the emirate dissolved into a

patchwork of city-states. In the

meantime, the Christian king-

doms that had managed to estab-

lish themselves in the north of the

Iberian peninsula were consoli-

dating their position and beginning

to expand southward. In 1085, Al-

fonso VI, the Christian king of

Castile, seized Toledo, one of An-

dalusia’ s main intellectual centers.

The new authorities continued to foster the artistic and

intellectual activities of their predecessors. To recoup

their recent losses, the Muslim rulers in Seville called on

fellow Muslims, the Almoravids---a Berber dynasty in

Morocco---to assist in halting the Christian advance.

Berber mercenaries defeated Castilian forces at Badajoz

in 1086 but then stayed in the area to establish their own

rule over the remaining Muslim-held areas in southern

Spain.

A warrior culture with no tolerance for heterodox

ideas, the Almoravids quickly brought an end to the era of

religious tolerance and intellectual

achievement. But the presence of

Andalusia’s new wa rlike rulers was

unable to stem the tide of Christian

advance. In 1215, Pope Innocent III

called for a new crusade to destroy

Muslim rule in southern Spain.

Over the next two hundred years,

Christian armies advanced relent-

lessly southward, seizing the cities

of Seville and C

ordoba. Only a

single redoubt of Abd al-Rathman’s

glorious achievement remained: the

remote mountain city of Granada,

with its imposing hilltop fortress,

the Alhambra.

CHRONOLOGY

Islam: The First Millennium

Life of Muhammad 570--632

Flight to Medina 622

Conquest of Mecca 630

Arabs seize Syria 640

Defeat of Persians 650

Election of Ali to caliphate 656

Muslim entry into Spain c. 710

Abbasid caliphate 750--1258

Construction of city of Baghdad 762

Reign of Harun al-Rashid 786--809

Ummayad caliphate in Spain 929--1031

Founding of Fatimid dynasty in Egypt 973

Capture of Baghdad by Seljuk Turks 1055

Seizure of Anatolia by Seljuk Turks 1071

First Crusade 1096

Saladin destroys Fatimid kingdom 1169

Mongols seize Baghdad 1258

Ottoman Turks capture Constantinople 1453

Atlantic

Ocean

M

e

d

i

t

e

r

r

a

n

e

a

n

S

e

a

Pyrenees

AFRICA

CASTILE

ARAGON

Toledo

Seville

Córdoba

Granada

Valencia

Badajoz

0 100 200 Miles

0 100 200 300 Kilometers

Christian-held areas

Spain in the Eleventh Century

170 CHAPTER 7 FERMENT IN THE MIDDLE EAST: THE RISE OF ISLAM

Islamic Civilization

Q

Focus Question: What were the main features of

Islamic society and culture during the era of early

growth?

To be a Muslim is not simply to worship Allah but also to

live according to his law as revealed in the Qur’an, which

is viewed as fundamental and immutable doctrine, not to

be revised by human beings.

As Allah has decreed, so must humans behave.

Therefore, Islamic doctrine must be consulted to deter-

mine questions of politics, economic behavior, civil and

criminal law, and social ethics. In Islamic society, there is

no demarcation between church and state, between the

sacred and the secular.

Political Structures

For early conv erts, establishing political institutions and

practices that c onformed to Islamic doctrine was a daunt-

ing task. In the first place, the will of Allah, as r ev ealed to

his Prophet, was not precise about the relationship between

religious and political authority, simply decreeing that hu-

man beings should ‘‘c onduct their affairs by mutual c on-

sent.’’ On a more practical plane, establishing political

institutions for a large and multicultural empire presented a

challenge for the Arabs, whose own political structur es were

relatively rudimentary and relevant only to small pastoral

communities (see the box abov e).

During the life of Muhammad, the problem c ould be

avoided, since he was gene rally accepted as both the reli-

gious and the political leader of the Islamic community---

the umma. His death, however, raised the question of

how a successor should be chosen and what authority

that person should have. As we have seen, Muhammad’s

immediate successors were called caliphs. Their authority

was purely temporal, although they were also considered

in general terms to be religious leaders, with the title of

imam. At first, each caliph was selected informally by

leading members of the umma. Soon succession became

hereditary in the Umayyad clan, but their authority was

still qualified, at least in theory, by the principles of

consultation with other leaders. Under the Abbasids, as

we saw earlier, the caliphs took on more of the trappings

of kingship and became more autocratic.

SAGE ADVICE FROM FATHER TO SON

Tahir ibn Husayn was born into an aristocratic fam-

ily in Central Asia and became a key political ad-

viser to al-Ma’mun, the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad

in the early ninth century. Appointed in 821 to a

senior position in Khurusan, a district near the city of Herat in

what is today Afghanistan, he wrote the following letter to his

son, giving advice on how to wield authority most effectively.

The letter so impressed al-Ma’mun that he had it widely distrib-

uted throughout his bureaucracy.

Letter of Tahir ibn Husayn

Look carefully into the matter of the land-tax which the subjects

have an obligation to pay. ... Divide it among the tax payers with

justice and fairness with equal treatment for all. Do not remove any

part of the obligation to pay the tax from any noble person just be-

cause of his nobility or any rich person because of his richness or

from any of your secretaries or personal retainers. Do not require

from anyone more than he can bear, or exact more than the usual

rate. ...

[The ruler should also devote himself] to looking after the

affairs of the poor and destitute, those who are unable to bring their

complaints of ill-treatment to you personally and those of wretched

estate who do not know how to set about claiming their rights. ...

Turn your attention to those who have suffered injuries and their

orphans and widows and provide them with allowances from the

state treasur y, following the example of the Commander of the

Faithful, may God exalt him, in showing compassion for them and

giving them financial support, so that God may thereby bring some

alleviation into their daily lives and by means of it bring you the

spiritual food of His blessing and an increase of His favor. Give pen-

sions from the state treasury to the blind, and give higher allowances

to those who know of the Qur’an, or most of it by heart. Set up

hospices where sick Muslims can find shelter, and appoint custo-

dians for these places who will treat the patients with kindness and

physicians who will cure their illnesses. ...

Keep an eye on the officials at your court and on your secretar-

ies. Give them each a fixed time each day when they can bring you

their official correspondence and any documents requiring the rul-

er’s signature. They can let you know about the needs of the various

officials and about all the affairs of the provinces you rule over.

Then devote all your faculties, ears, eyes, understanding and intel-

lect, to the business they set before you: consider it and think about

it repeatedly. Finally take those actions which seem to be in accor-

dance with good judgment and justice.

Q

How does Tahir’s advice compare with that given in the

political treatise Arthasastra, discussed in Chapter 2? Would

Tahir’s letter provide an effective model for political leadership

today?

ISLAMIC CIVILIZ ATION 171

The Wealth of Araby: Trade and Cities

in the Middle East

Overall, as we have noted, this era was probably one of the

most prosperous periods in the history of the Middle East.

Trade flourished, not only in the Islamic world but also with

China (now in a period of effloresc enc e during the era of the

Tang and the Song dynasties---see Chapter 10), with the

Byzantine Empire, and with the trading societies in

Southeast Asia (see Chapter 9). Trade goods were carried

both b y ship and b y the ‘‘fleets of the desert,’’ the camel

caravans that traversed the arid land from Moroc c o in the

far west to the countries beyond the Caspia n Sea. From West

Africa came gold and slaves; from China, silk and porcelain;

from East Africa, gold, ivory, and rhinoceros horn; and from

the lands of South Asia, sandal w ood, cotton, wheat, sug ar,

and spices. W ithin the empire, Egypt contributed grain;

Iraq, linens, dates, and precious stones; Spain, leather goods,

olives, and wine; and western India, various textile goods.

The exchange of goods was facilitated by the development of

banking and the use of currency and letters of cr edit (see the

comparative essay ‘‘Trade and Civilization’’ on p. 173).

Under these conditions, urban areas flourished.

While the Abbasids were in power, Baghdad was probably

the greatest city in the empire, but after the rise of the

Fatimids in Egypt, the focus of trade shifted to Cairo,

described by the traveler Leo Africanus as ‘‘one of the

greatest and most famous cities in all the whole world,

filled with stately and admirable palaces and colleges, and

most sumptuous temples.’’

6

Other great commercial cities

included Basra at the head of the Persian Gulf, Aden at

the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula, Damascus in

modern Syria, and Marrakech in Morocco. In the cities,

the inhabitants were generally segregated by religion, with

Muslims, Jews, and Christians living in separate neigh-

borhoods. But all were equally subject to the most com-

mon threats to urban life---fire, flood, and disease.

The most impressive urban buildings were usually

the palace for the caliph or the local governor and the

great mosque. Houses were often constructed of stone or

brick around a timber frame. The larger houses were

often built around an interior courtyard, where the resi-

dents could retreat from the dust, noise, and heat of the

city streets. Sometimes domestic animals such as goats or

sheep would be stabled there. The houses of the wealthy

were often multistoried, with balconies and windows

covered with latticework to provide privacy for those

inside. The poor in both urban and rural areas lived in

simpler houses composed of clay or unfired bricks. The

Bedouins lived in tents that could be dismantled and

moved according to their needs.

The Arab Empire was clearly more urbanized than

most other areas of the known world at the time. Yet the

bulk of the population continued to live in the country-

side, supported by farming or herding animals (see the

comparative illustration on p. 174). During the early

stages, most of the farmland was owned by independent

peasants, but eventually some concentration of land in

the hands of wealthy owners began to take place. Some

lands were owned by the state or the court and were

cultivated by slave labor, but plantation agriculture was

not as common as would be the case later in many areas

of the world. In the valleys of rivers such as the Tigris, the

Euphrates, and the Nile, the majority of the farmers were

probably independent peasants.

Eating habits varied in accordance with economic

standing and religious preference. Muslims did not eat

pork, but those who could afford it often served other

meats such as mutton, lamb, poultry, or fish. Fruit, spices,

and various sweets were delicacies. The poor were gen-

erally forced to survive on boiled millet or peas with an

occasional lump of meat or fat. Bread---white or whole

meal---could be found on tables throughout the region

except in the deserts, where boiled grain was the staple

food.

Islamic Society

In some ways, Arab society was probably one of the most

egalitarian of its time. Both the principles of Islam, which

held that all were equal in the eyes of Allah, and the

importance of trade to the prosperity of the state

probably contributed to this egalitarianism. Although

there was a fairly well defined upper class, consisting of

the ruling families, senior officials, tribal elites, and the

wealthiest merchants, there was no hereditary nobility as

in many contemporary societies, and the merchants en-

joyed a degree of respect that they did not receive in

Europe, China, or India.

Not all benefited from the high degree of social

mobility in the Islamic world, however. Slavery was

widespread. Since a Muslim could not be enslaved, the

supply came from sub-Saharan Africa or from non-

Islamic populations elsewhere in Asia. Most slaves were

employed in the army (which was sometimes a road to

power, as in the case of the Mamluks) or as domestic

servants, who were sometimes permitted to purchase

their freedom. The slaves who worked the large estates

experienced the worst living conditions and rose in revolt

on several occasions.

The Islamic principle of human equality also fell

short, as in most other societies of the day, in the treat-

ment of women. Although the Qur’an instructed men to

treat women with respect, and women did have the right

to own and inherit property, in general the male was

dominant in Muslim society. Polygyny was permitted,

172 CHAPTER 7 FERMENT IN THE MIDDLE EAST: THE RISE OF ISLAM

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

T

RADE AND CIVILIZATION

In 2002, archaeologists unearthed the site of an

ancient Egyptian port city on the shores of the Red

Sea. Established sometime during the first millen-

nium

B.C.E., the city of Berenike linked the Nile

River valley with ports as far away as the island of Java in

Southeast Asia. The discovery of Berenike is only the latest

piece of evidence confirming the importance of interregional

trade since the beginning of the historical era. The exchange of

goods between far-flung societies became a powerful engine be-

hind the rise of advanced civilizations throughout the ancient

world. Raw materials such as copper, tin, and obsidian; items

of daily necessity like salt, fish, and other foodstuffs; and luxury

goods like gold, silk, and precious stones passed from one end

of the Eurasian supercontinent to the other, across the desert

from the Mediterranean Sea to sub-Saharan Africa, and through-

out much of the Americas. Less well known but also important

was the maritime trade that stretched from the Mediterranean

across the Indian Ocean to port cities on the distant coasts of

Southeast and East Asia.

During the first millennium

C.E., the level of interdependence among

human societies intensified as three major trade routes---across the

Indian Ocean, along the Silk Road, and by caravan across the

Sahara---created the framework of a single system of trade. The new

global network was informational as well as commercial, transmit-

ting technology and ideas, such as the emerging religions of Bud-

dhism, Christianity, and Islam, to new destinations. There was a

close relationship between missionary activities and trade. Buddhist

merchants brought the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama to China,

and Muslim traders carried Muhammad’s words to Southeast Asia

and sub-Saharan Africa. Indian traders carried Hindu beliefs and

political institutions to Southeast Asia.

What caused the rapid expansion of trade during this

period? One key factor was the introduction of technology that

facilitated transpor tation. The development of the compass,

improved techniques in mapmaking and shipbuilding, and

greater knowledge of w ind pattern s all contributed to the expan-

sion of maritime trade. Caravan trade, once carried by wheeled

chariots or on the backs of oxen, now used the camel as the

preferred beast of burden through the deserts of Africa, Central

Asia, and the Middle East.

Another reason for the expansion of commerce during this pe-

riod was the appearance of several multinational empires that cre-

ated zones of stability and affluence in key areas of the Eurasian

landmass. Most important were the emergence of the Abbasid Em-

pire in the Middle East and the prosperity of China during the Tang

and Song dynasties (see Chapter 10). The Mongol invasions in the

thirteenth century temporarily disrupted the process but then

established a new era of stability that fostered long-distance trade

throughout the world.

The importance of interregional trade as a crucial factor in pro-

moting the growth of human civilizations can be highlighted by

comparing the social, cultural, and technological achievements of ac-

tive trading states with those communities that have traditionally

been cut off from contacts w ith the outside world. We shall encoun-

ter many of these communities in later chapters. Even in the West-

ern Hemisphere, where regional trade linked societies from the

Great Plains of North America to the Andes Mountains in present-

day Peru, geographic barriers limited the exchange of inventions and

ideas, putting these societies at a distinct disadvantage when the first

contacts with peoples across the oceans occurred at the beginning of

the modern era.

Q

What were the chief factors that led to the expansion of

interregional trade during the first millennium

C.E.? How did the

growth of international trade contacts affect other aspects of

society?

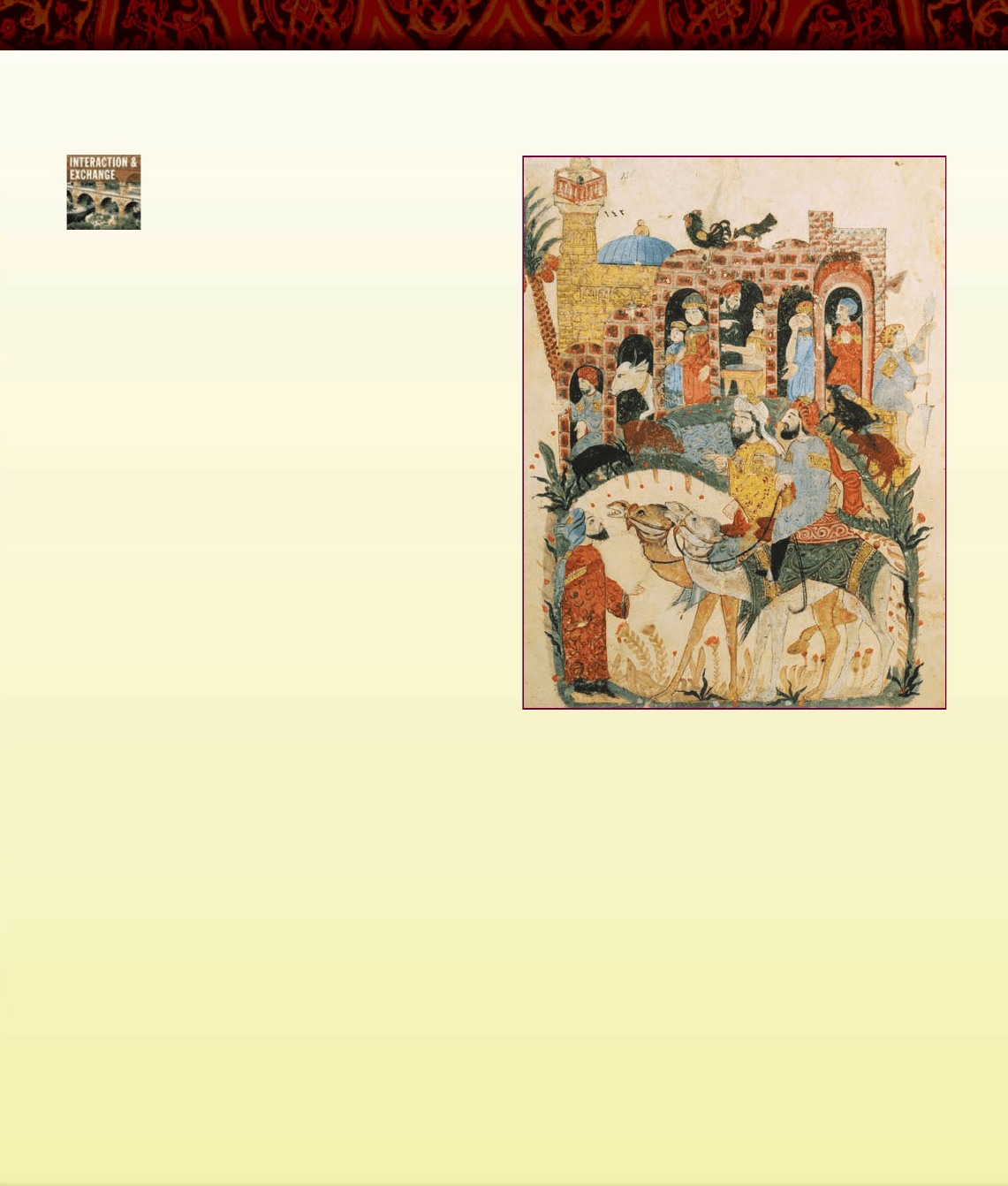

Arab traders in a caravan

c

Art Resource, NY

ISLAMIC CIVILIZ ATION 173