Douce A.P. Thermodynamics of the Earth and Planets

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

208 The Second Law of Thermodynamics

commonly symbolized by S

0

298

, as:

S

0

298

=

298.15

0

dQ

rev

T

dT (4.69)

with S(0) =0 if the substance is a perfect crystal at absolute zero. If configurational entropy

is not zero at 0 K then it must be added to (4.69) (more on this in Chapter 7). If there are

no phase transitions between 0 K and 298.15 K (which is the case for the three examples

shown in Fig. 4.8) then this integral is equal to (4.66) and is simply the area under the

curves in Fig. 4.8. If there are phase transitions between 0 K and 298.15 K then the entropy

changes associated to the phase transitions must be added to (4.69), as discussed in Worked

Example 4.4.

Values of reference state Third Law entropies are listed in thermodynamic data bases. It is

important to reiterate this point: reference states entropies are not “entropies of formation”.

An entropy of formation could be defined as the difference between the Third Law entropy

of a compound and those of its constituent elements. If we call this difference (S

0

298

), then:

S

0

298

=S

0

298

−

elements

S

0

298, elements

(4.70)

but, by (4.66), S

0

298, elements

= 0 for all elements, so (S

0

298

) = S

0

298

for all substances.

Entropies of formation are seldom, if ever, used. The point of 4.70 is to make clear the

difference between reference state entropy and reference state enthalpy of formation.

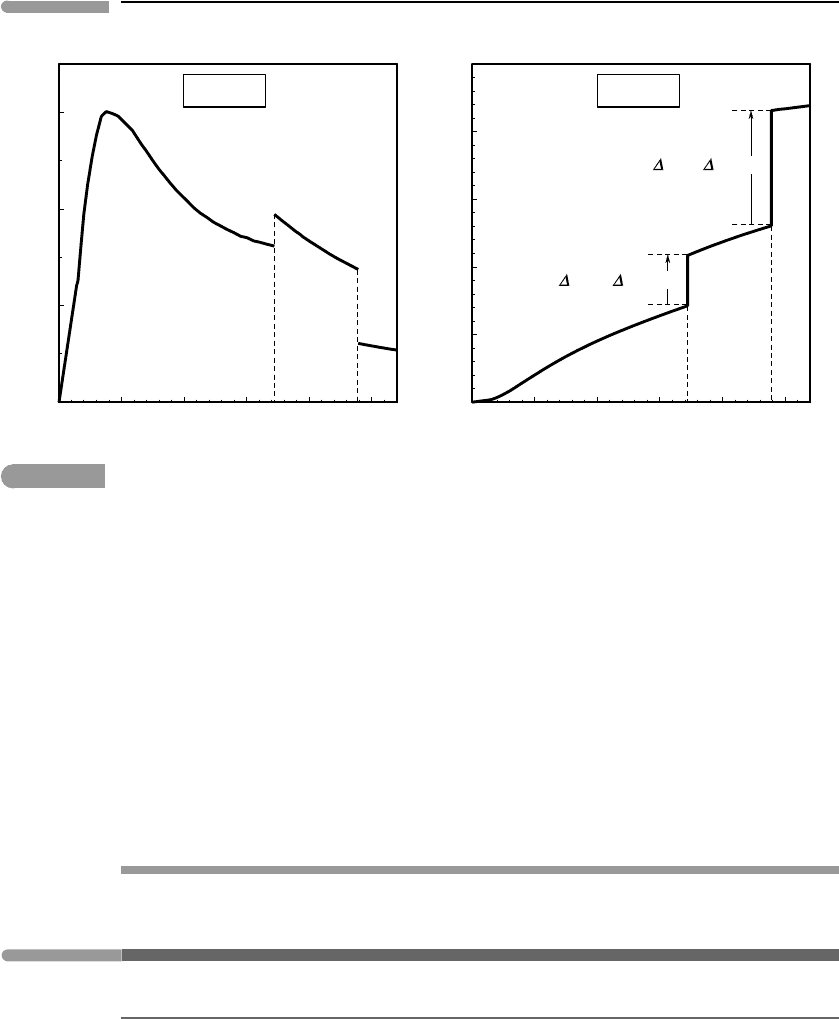

Worked Example 4.4 Entropies of phase transitions

Heat capacity becomes undetermined at phase transitions, because the system absorbs heat

without experiencing a temperature change. In Chapter 1 we discussed this concept in

terms of sensible heat and latent heat, and saw that the enthalpy associated with a phase

transition must be treated separately from the heat capacity integrals that track enthalpy

changes associated with sensible heat (see Section 1.13.2). The same is true of entropy:

if phase transitions occur within the temperature range that one is integrating over (e.g.

equation (4.69)), then the entropy of the phase transitions, calculated as discussed in Worked

Example 4.1, must be added separately. A simple example is the element chlorine, which

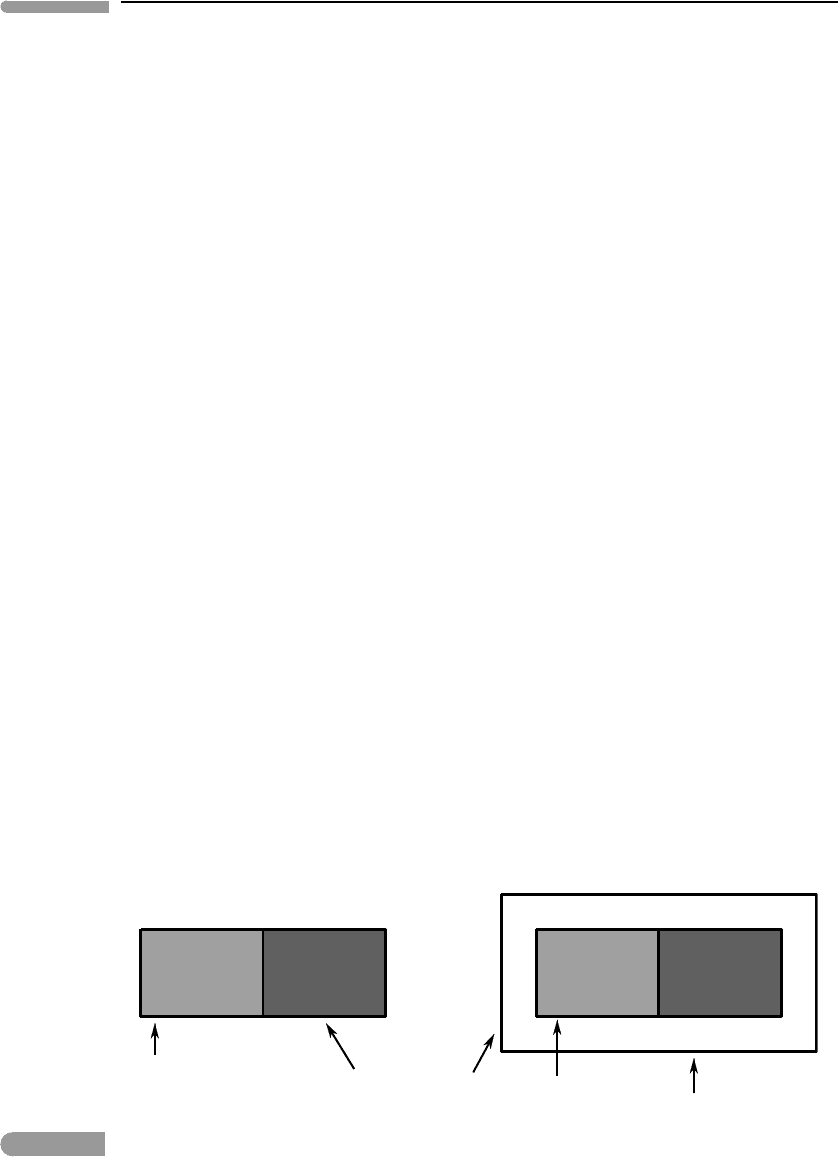

melts at 172.12 K and vaporizes at 239.05 K. Figure 4.9a shows values of C

P

/T for chlorine

between 0 K and 270 K, measured by Giauque and Powell (1939). There are three different

curves, separated by two discontinuities that correspond to the two phase transitions, melting

and vaporization. The area under each of the curves corresponds to the contribution of each

of the phases to the Third Law entropy of chlorine at 270 K, but the entropies associated

with the phase transitions are not accounted for in this figure.

Third Law entropy of chlorine is plotted as a function of temperature in Fig. 4.9b. The

entropy for the solid at any temperature between 0 K and 172.12 K is equal to the area

under the first curve in Fig. 4.9a between 0 K and that temperature. The entropy of liquid

chlorine at the melting point of 172.12 K is equal to the entropy of the solid at the melting

point plus the entropy of melting, which is equal to the enthalpy of melting divided by

the melting temperature (Worked Example 4.1). We then add the area under the second

curve in Fig. 4.9a to get the entropy of liquid chlorine at the vaporization point, 239.05K.

This, plus the entropy of vaporization (= enthalpy of vaporization divided by temperature

of vaporization), yields the entropy of chlorine gas at 239.05 K, and so on.

209 4.8 Thermodynamic potentials

0 50 100 150 200 250

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

T (K)

0 50 100 150 200 250

0

50

100

150

200

250

T (K)

solid solidliquid gas liquid gas

S

v

= H

v

/T

v

S

m

= H

m

/T

m

(a)

(b)

Chlorine Chlorine

C

P

/T(J K

–2

mol

–1

)

S

(J K

–1

mol

–1

)

Fig. 4.9

Heat capacity, phase transitions and Third Law entropy of chlorine. Data from Giauque and Powell (1939).

The existence of a non-zero enthalpy of transition causes the entropy to be discontinuous

at the phase transition, as this example shows. For reasons that we discuss in Chapter 7,a

phase transition of this type, in which there is an entropy discontinuity and H

transition

=0,

is called a first-order phase transition. Melting, sublimation, vaporization and polymorphic

transformations (such as graphite

→

←

diamond or kyanite

→

←

sillimanite) are common exam-

ples of first-order phase transitions. Continuous (or “second-order”) phase transitions, in

which entropy is continuous (and thus H

transition

=0) are important in the study of fluids

(Chapter 9) and also occur in some minerals (Chapter 8).

The entropy discontinuity associated with first-order phase transitions reflects a discon-

tinuity in the number of accessible microstates. A simplified view is as follows. In the

solid there are vibrational degrees of freedom only. At the melting point rotational degrees

of freedom appear, and so the energy of the molecules can be distributed over a greater

number of microstates. Even more microstates appear when the substance vaporizes and

translational degrees of freedom become available.

4.8 Thermodynamic potentials

4.8.1 The entropy maximum principle revisited

The goal of the rest of this chapter is to develop a formal thermodynamic definition of chem-

ical equilibrium, that will allow us to calculate phase equilibrium and phase compositions

in planetary environments. In order to reach that goal and to understand where each result

comes from we must follow a somewhat tortuous path that I will try to simplify as much

as possible without losing any of the necessary physical and mathematical justifications.

We begin by re-stating the Second Law of Thermodynamics in a formal mathematical lan-

guage. The Second Law says that the entropy of an isolated system can only increase, or,

210 The Second Law of Thermodynamics

equivalently, that the state of equilibrium in an isolated system is the one in which entropy

takes its maximum possible value for the (constant) total internal energy content of the

system (we will ignore forms of energy other than E). By definition, an isolated system

does not interact with anything else, so we see that the condition dE =0 (i.e constant inter-

nal energy) must be true of an isolated system. It must also be true that dV = 0, because

otherwise the system would exchange work with its environment. Moreover, an isolated

system must also be closed to the exchange of chemical components. If we call the mol

number (= number of mols) of the ith component n

i

, then for an isolated system it must be

dn

i

=0, for all i.

In the mathematical notation of thermodynamics, the maximum entropy statement of the

Second Law is often written as follows:

dS

E,V , n

i

=0 (4.71)

d

2

S

E,V , n

i

< 0. (4.72)

These are mangled versions of the conditions for the maximum of a function: the first

equation says that the first derivative vanishes at an extremum, whereas the second one says

that, if the second derivative is negative at the extremum, then the extremum is a maximum.

The problem is that equations (4.71) and (4.72) are not written in terms of derivatives, but

rather in terms of the total differentials of entropy. This notation is mathematically sloppy,

as loudly pointed out by Truesdell (1984), but, regrettably, the use of equations such as

(4.71) and (4.72) is so deeply ingrained in thermodynamics that it is difficult to get away

from it. It is important, however, to understand what these equations are actually saying.

In particular, if E, V and n

i

are all constant, exactly what variable are we differentiating

entropy relative to, so as to find an extremum for the function? Which begs the question:

what (else) is entropy a function of? Or, in physical terms, why is entropy changing in the

first place?

The way to think about this is by imagining that, initially, there are restrictions, or

constraints, that prevent the system from changing towards equilibrium. For instance,

a partition separating two different gases that can mix by diffusion, or two different

electrolyte solutions that will precipitate a solid when they mix, or a perfect thermal insula-

tor separating two bodies at different temperatures. When we remove the restriction the

system changes towards equilibrium, and as it does so entropy changes as a function

of some physical quantity that drives the displacement towards equilibrium. This could

be, for example, exchange of gas molecules between the two sides of the container in

Fig. 4.7, or exchange of ions between the electrolyte solutions, or exchange of internal

energy between two bodies at different temperatures. We will analyze the latter exam-

ple in formal mathematical language so as to clarify the meaning of equations (4.71)

and (4.72).

At constant E, V and n

i

, the entropy of the isolated system varies as a function of

the amount of internal energy exchanged between the two bodies. Let the internal energy,

entropy and temperature of body j be E

j

, S

j

and T

j

, respectively, and the corresponding

properties of the isolated system composed of the two bodies be E, S and T. We will assume

that there is no exchange of matter between the bodies, and that they are incompressible.

We then have:

E

1

+E

2

=E (4.73)

211 4.8 Thermodynamic potentials

and, because the system is isolated (E constant):

dE

1

dE

2

=−1. (4.74)

We will track the change in entropy of the system relative to the internal energy content

of one of the bodies, say 1, at constant internal energy of the system. For an extremum we

need the first derivative to vanish, so that:

∂S

∂E

1

E,V , n

i

=0. (4.75)

This is the same equation as (4.71), except that now we are explicitly stating how to calculate

the derivative. Using the fact that entropy is an extensive variable, we expand (4.75)as

follows:

∂S

∂E

1

E,V , n

i

=

∂S

1

∂E

1

E,V , n

i

+

∂S

2

∂E

1

E,V , n

i

=0 (4.76)

and using (4.74):

∂S

∂E

1

E,V , n

i

=

∂S

1

∂E

1

E,V , n

i

−

∂S

2

∂E

2

E,V , n

i

=0. (4.77)

From (4.14) and the properties of partial derivatives (Box 1.3, equation (1.3.18)), this

becomes:

∂S

∂E

1

E,V , n

i

=

1

T

1

−

1

T

2

=0, (4.78)

which says that the entropy of the closed system takes an extremum value when T

1

= T

2

.

We know, of course, that this is the equilibrium condition, but equation (4.78) by itself does

not prove it, because it does not tell us whether the extremum is a maximum or a minimum.

In order to test for this we need to find the sign of the second derivative, so we write the

formal equation equivalent to (4.72):

∂

2

S

∂E

2

1

E,V , n

i

=

∂

∂E

1

∂S

∂E

1

E,V , n

i

=

d

dE

1

1

T

1

−

1

T

2

(4.79)

or, using (4.74):

∂

2

S

∂E

2

1

E,V , n

i

=

d

dE

1

1

T

1

+

d

dE

2

1

T

2

. (4.80)

From the chain rule:

d

dE

1

T

=

d

dT

1

T

dT

dE

=−

1

T

2

dT

dE

(4.81)

212 The Second Law of Thermodynamics

and, since we assume that the bodies are incompressible, heat transfer is at constant volume,

so, using (1.13.18):

dT

dE

=

1

C

V

. (4.82)

Putting it all together, and noting that C

V

is always a positive quantity, we arrive at:

∂

2

S

∂E

2

1

E,V , n

i

=−

1

C

V

T

2

1

−

1

C

V

T

2

2

< 0, (4.83)

which is the equivalent of (4.72) and shows that entropy is indeed maximum when T

1

=T

2

.

As an aside, because the isolated system consists of the two bodies only, this result also

shows that the equilibrium temperature of the system, T, is uniform and equal to that of the

two bodies.

Exchange of internal energy is the only restriction that we are allowed to impose and

release in our example, so that it is the only variable relative to which we can track entropy

changes in the isolated system. Other restrictions are in general possible, such as exchanges

of chemical components, PdV work, electric work or radiant energy between different

parts of an isolated system. There may also be more than one independent restriction, a

point that will become important when we study chemical equilibrium, so that we may

need more than one variable to track the total entropy change. We will use the symbol

Z

k

to represent the independent variables that represent the quantities that are exchanged

between parts of an isolated system when restrictions are released and the system evolves

spontaneously towards equilibrium. The equilibrium condition, or, if you wish, the Second

Law of Thermodynamics, is then written as follows:

dS

E,V , n

i

=

k

∂S

∂Z

k

E,V , n

i

dZ

k

=0; dZ

k

=0 (4.84)

and:

d

2

S

E,V , n

i

=

k,j

∂

∂Z

j

∂S

∂Z

k

E,V , n

i

dZ

j

dZ

k

< 0; dZ

j

=0, dZ

k

=0. (4.85)

In our example there is only one restriction, because changes in E

1

and E

2

are not indepen-

dent (equation (4.74)), and the quantity whose flow drives the system towards equilibrium

is internal energy. These equations then become:

dS

E,V , n

i

=

∂S

∂E

1

E,V , n

i

dE

1

=0; dE

1

=0 (4.86)

and:

d

2

S

E,V , n

i

=

∂

∂E

1

∂S

∂E

1

E,V , n

i

(

dE

1

)

2

< 0; dE

1

=0, (4.87)

which, given the condition dE

1

=0 are identical to (4.78) and (4.83), respectively. Through-

out the rest of this book I will use both notations. I think that it is important to become familiar

not only with the one that is widely used in thermodynamics (e.g. dS = 0) but also with the

one that is mathematically complete (e.g. ∂S/∂Z =0). This is a point that is unfortunately

not made in most thermodynamics textbooks. You can always refer to equations (4.84) and

(4.85) to clarify the relationship between the two notations.

213 4.8 Thermodynamic potentials

4.8.2 The energy minimum principle

We now have a formal mathematical statement that defines thermodynamic equilibrium

(equations (4.84) and (4.85)), but this definition is unwieldy on two accounts. In the first

place, it is based on entropy, which is neither an intuitively simple concept nor a quantity

that is directly observable. Second, it only applies to isolated systems, and in nature we

frequently have to deal with systems that are not isolated. We will now take care of these

difficulties. The first step is to recast the Second Law of Thermodynamics in terms of an

extremum in internal energy rather than entropy. The full justification for doing this will

become apparent a posteriori. At this stage let us view it as a simple exercise in calculus:

can we start from (4.84) and (4.85) and obtain equivalent (NOT identical !!) expressions

for ∂E/∂Z and ∂

2

E/∂Z

2

? In particular, what can we say about the internal energy of a

constant-entropy system at equilibrium?

We first seek an expression for (∂E/∂Z)

S

in terms of (∂S/∂Z)

E

. Using equation (1.3.19)

(Box 1.3), and omitting the subscripts V and n

i

because these variables stay constant

throughout, we write:

∂E

∂Z

S

=−

∂E

∂S

Z

∂S

∂Z

E

=−T

∂S

∂Z

E

. (4.88)

If (∂S/∂Z)

E

vanishes, then so does (∂E/∂Z)

S

. Thus, an extremum for entropy at constant

internal energy is also an extremum for internal energy at constant entropy. We now have

to decide whether it is a minimum or a maximum, so we take the second derivative. To

simplify the notation, we make (∂E/∂Z)

S

=Y . Then, using (1.3.12) (Box 1.3):

∂

2

E

∂Z

2

S

=

∂Y

∂Z

S

=

∂Y

∂Z

E

+

∂Y

∂E

Z

∂E

∂Z

S

, (4.89)

which, using (4.88) and the fact that at an extremum it is (∂E/∂Z)

S

=0, simplifies to:

∂

2

E

∂Z

2

S

=

∂Y

∂Z

E

=

∂

∂Z

∂E

∂Z

S

E

=

∂

∂Z

(

−T

)

∂S

∂Z

E

E

. (4.90)

If you are wondering whether it is licit to use the condition (∂E/∂Z)

S

= 0 to simplify

(4.89), but ignore this simplification in (4.90), it is. The reason is that in (4.90)weare

evaluating (∂

2

E/∂Z

2

)

S

in general, and (∂E/∂Z)

S

= 0 is only a special point. We could

carry over the last term in (4.89) to the end of the calculation, and drop it there. The result

would be the same, because we are not operating on this term any further, but why make

the equations any more messy than they have to be?

Applying the product rule to the right-hand side of (4.90), and using the extremum

condition (∂S/∂Z)

E

=0, we have:

∂

2

E

∂Z

2

S

=−

∂T

∂Z

E

∂S

∂Z

E

−T

∂

2

S

∂Z

2

E

=−T

∂

2

S

∂Z

2

E

> 0, (4.91)

where the inequality, which shows that this extremum is a minimum, follows directly from

(4.85), i.e. the fact that S at constant E is a maximum at equilibrium: (∂

2

S/∂Z

2

)

E

<0.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics therefore leads to a minimum energy princi-

ple: at equilibrium in a constant entropy system the internal energy takes it mini-

mum possible value. In the notation of thermodynamics we write the minimum energy

214 The Second Law of Thermodynamics

principle as follows:

dE

S,V , n

i

=0 (4.92)

d

2

E

S,V , n

i

> 0, (4.93)

which can also be expanded in a way analogous to (4.84) and (4.85) (exercise left for the

reader).

The entropy maximum and the energy minimum principles are both valid definitions of

thermodynamic equilibrium. To understand what this means, you should now do Exercise

4.7, in which you are asked to prove the condition of thermal equilibrium (T

1

= T

2

) in a

constant entropy system, by developing a set of equations for the derivatives of internal

energy that parallels equations (4.73)to(4.83). It is necessary to be extremely careful here,

though. The equilibrium state defined by equations (4.92) and (4.93) is not the same as

the one defined by equations (4.71) and (4.72). It cannot possibly be, as in the first case we

are dealing with an isolated system and in the second case we are not. If entropy were kept

constant in an isolated system then the system would not change and the minimum energy

principle would be meaningless, because internal energy would not be able to change. In

order for constant entropy minimization of the internal energy to be possible, the system of

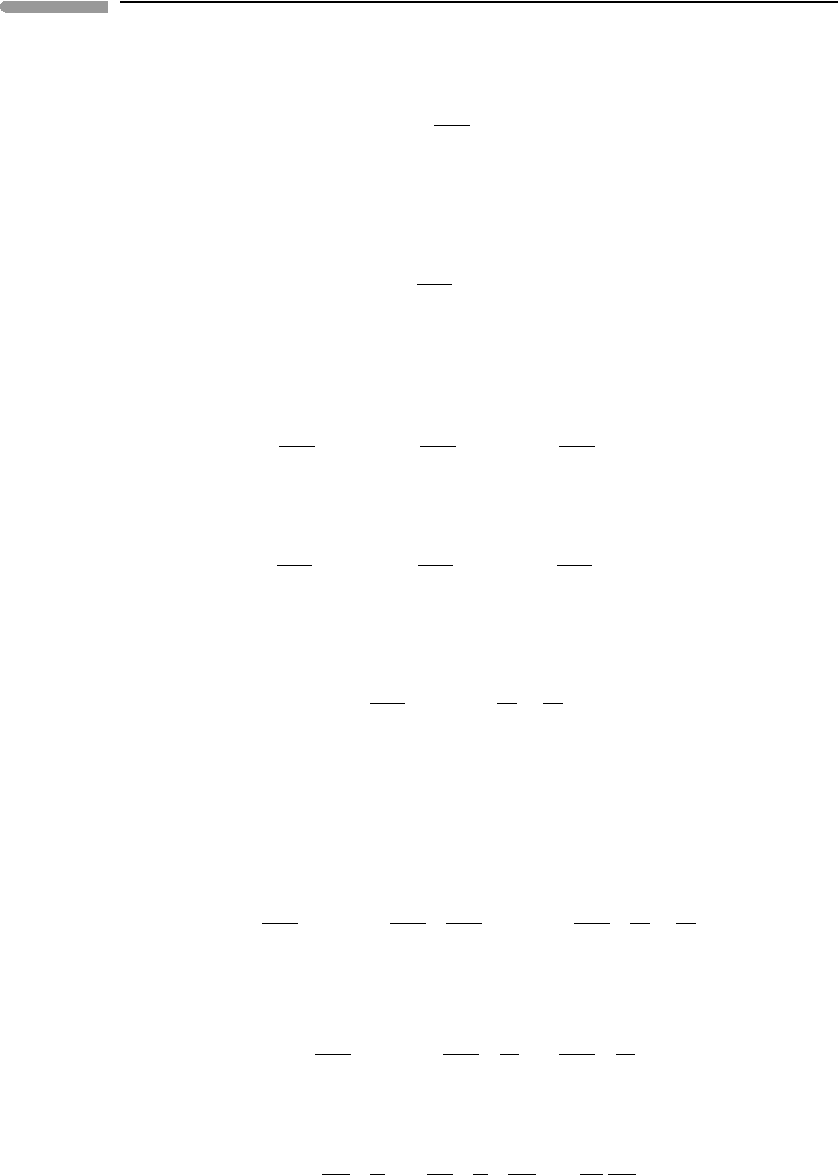

interest must be part of a larger isolated system in which entropy does increase. Consider

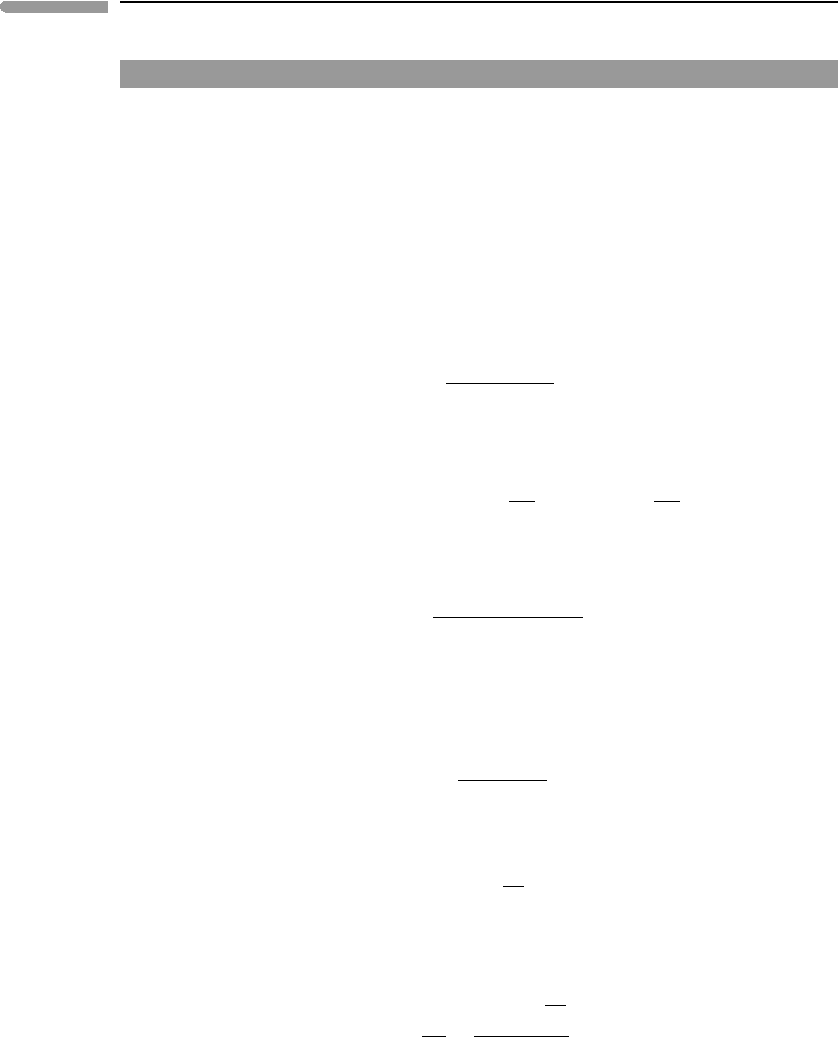

again the example of the two bodies at different temperatures, T

2

>T

1

, shown now in

Fig. 4.10. If we want to achieve thermal equilibrium at constant internal energy (case I)

then the two bodies must make up an isolated system, A in the figure. This is the situation

considered in Section 4.8.1. If, on the other hand, we want to achieve thermal equilibrium

at constant entropy, which is the situation considered in this section (case II), then system A

cannot be isolated. It must be able to exchange energy with its surroundings, which conform

an isolated system, labeled B in the figure, and the entropy of B must increase. In order for

the entropy of B to increase there must be heat transfer between A and the rest of B. Because

equilibrium of A at constant entropy requires that its internal energy be minimized, heat

must be transferred from A to its surroundings. Therefore, the final temperature of A if it is

allowed to reach equilibrium at constant entropy must be lower than its final temperature

if it reaches equilibrium at constant internal energy.

T

1

T

2

T

1

T

2

(I) (II)

Isolated system

boundary

A: constant E

A: constant S

B: constant E

Fig. 4.10

(I) Thermal equilibrium at constant energy maximizes entropy in isolated system A. (II) Thermal equilibrium at

constant entropy minimizes internal energy in isentropic but non-adiabatic system A, and maximizes entropy in a

larger isolated system B.

215 4.8 Thermodynamic potentials

Worked Example 4.5 Heat flow at constant energy and at constant entropy

We reached the conclusion in the last sentence on the basis of physical arguments only. We

will now derive it formally. Consider Fig. 4.10 again. Let the initial temperatures of the two

bodies, T

2

>T

1

, and their masses, m

1

and m

2

, be the same in both thought experiments,

I and II in the figure. We will call the final equilibrium temperatures reached at constant

internal energy (case I) and constant entropy (case II) T

E

and T

S

, respectively. The constant

energy condition is:

E =E

1

+E

2

=m

1

C

V

(

T

E

−T

1

)

+m

2

C

V

(

T

E

−T

2

)

=0 (4.94)

from which we get:

T

E

=

m

1

T

1

+m

2

T

2

m

1

+m

2

. (4.95)

From the constant entropy condition, and assuming that heat capacities are constant:

S = S

1

+S

2

=m

1

C

V

T

s

T

1

dT

T

+m

2

C

V

T

s

T

2

dT

T

=0 (4.96)

we get:

ln T

S

=

m

1

ln T

1

+m

2

ln T

2

m

1

+m

2

. (4.97)

We can now make m

2

=km

1

, with k>0, and T

2

=hT

1

, with h>1. These two conditions

cover all possible situations: T

2

is always greater than T

1

, but either of the two bodies can

be larger, and by any factor that we wish. Substituting into (4.95) and (4.97) we get:

T

E

=

T

1

(

1 +kh

)

1 +k

(4.98)

and:

T

S

=T

1

h

k

1+k

. (4.99)

Take the ratio T

S

/T

E

:

R =

T

S

T

E

=

(

1 +k

)

h

k

1+k

1 +kh

. (4.100)

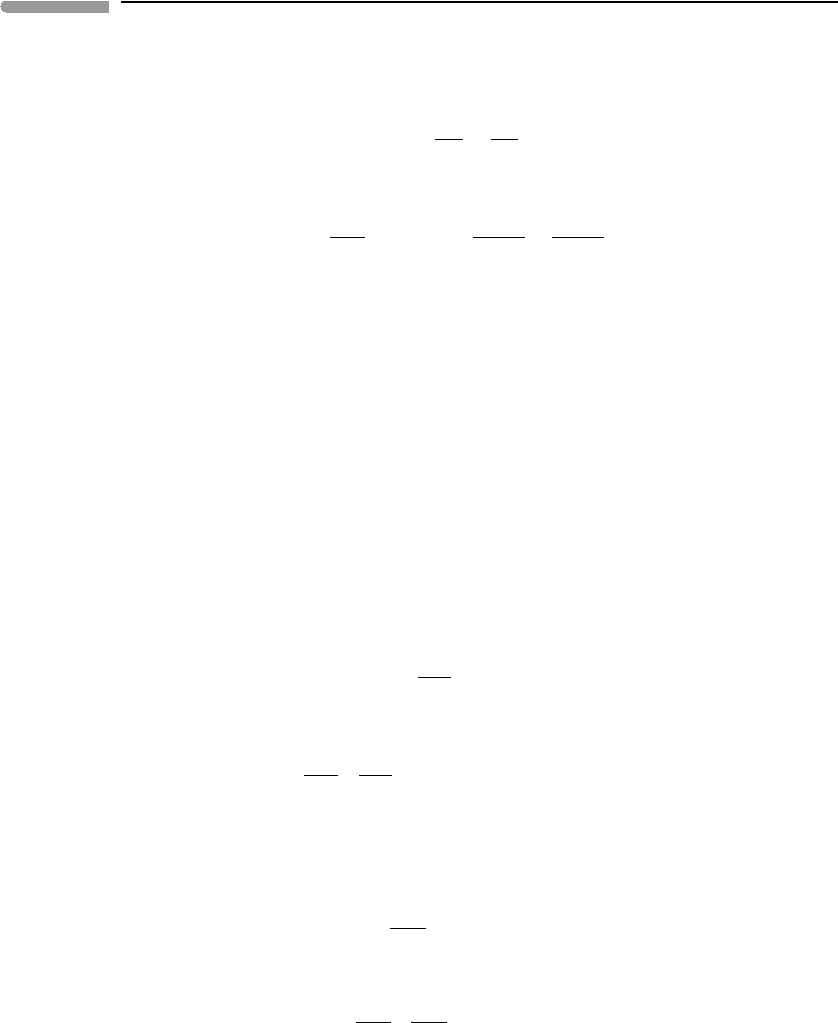

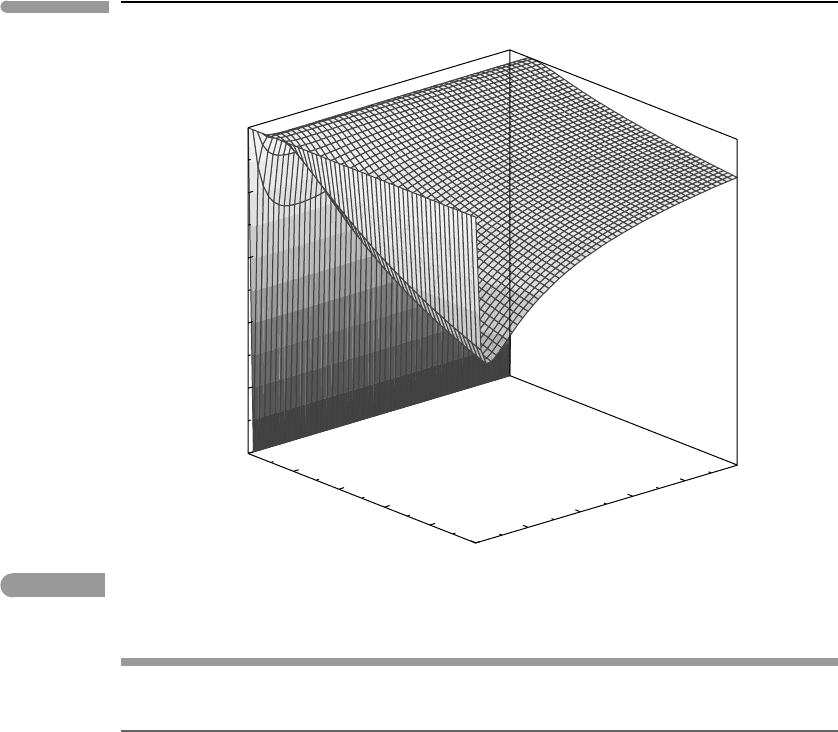

For k>0 and h>1, we find that R<1, always. This is shown in Fig. 4.11, that shows

that the equilibrium temperature at constant entropy (case II) is always lower than the

equilibrium temperature at constant internal energy (case I). If one of the bodies becomes

much larger than the other one (k →0ork →∞) then R approaches 1, which is also what

one should expect. The effect of varying initial temperature contrast (parametrized by h) is,

however, very asymmetric.

216 The Second Law of Thermodynamics

0

2

4

6

8

1

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

k

h

R

Fig. 4.11 The R = T

S

/T

E

, ratio of final temperature for the constant entropy process to final temperature for the constant

energy process, for the systems in Fig. 4.10, as a function of the ratio between the masses of the (h) and the ratio

between their initial temperatures (k).

4.8.3 Internal energy as a thermodynamic potential

Internal energy is one of several thermodynamic potentials. The name comes from analogy

with potentials in mechanics. Thermodynamic equilibrium is attained when a thermody-

namic potential is minimized subject to specific constraints. In the case of E these are:

constant entropy, volume and chemical composition, and the release of some internal restric-

tions of the system, for example, removal of a partition between different gases or solutions,

or of an insulating wall between bodies at different temperatures. Mechanical equilibrium

is attained when a mechanical potential (= potential energy per unit mass, Section 1.3.1)

is minimized. For example, a mountain range is not in mechanical equilibrium because

it has potential energy relative to the geoid (equipotential surface), which sets the mini-

mum potential level. When restrictions are released, for example by weathering, erosion

drives the surface of the planet towards mechanical equilibrium by lowering its gravita-

tional potential. Equilibrium would be attained if the surface of the planet were to become

everywhere identical to its equipotential surface. This state of mechanical equilibrium is

easily achieved in fluid planets but not in solid bodies.

When we discussed the entropy maximum and energy minimum principles we explicitly

stated that they applied to systems that are closed to changes in chemical composition,

which we specified with the subscript n

i

, meaning that the mol number of component i

remains constant, for all is. When studying natural systems we have to make allowance for

the possibility that changes in chemical composition may occur. In order to do this we add a

217 4.8 Thermodynamic potentials

term to equation (4.12) that accounts for changes in internal energy that arise from possible

changes in chemical composition. The equation becomes:

dE =TdS −PdV +

i

µ

i

dn

i

. (4.101)

The extensive variable n

i

is the mol number (= number of mols) of chemical component i,

and µ

i

is an intensive variable called the chemical potential of i. The definition of chemical

potential follows immediately from (4.101):

µ

i

=

∂E

∂n

i

S, V , n

j=i

. (4.102)

The chemical potential of component i in a thermodynamic system is the first derivative

of the internal energy of the system relative to the mol number of i, taken while keeping

S, V and the mole numbers of all other components, j =i, constant. If you prefer physical

terms, the chemical potential of a chemical species i keeps track of how the internal energy

of the system varies when the amount of i varies by an infinitesimal amount, everything else

being held constant. Chemical potential will play a central role in much of the remainder of

this book. We shall soon see that there are alternative definitions of µ

i

that are better suited

to solving problems in chemical equilibrium. It must be absolutely clear, however, that no

matter how one defines it, the chemical potential is always one and the same variable and,

everything else being the same, it has a single and well-defined value. It is no different

from the other two intensive variables in equation (4.102), temperature and pressure: no

matter how one chooses to define or measure them, their physical meaning and magnitude

are the same.

Equation (4.101) is called a fundamental equation, and the variables S, V and n

i

, are

called the natural variables for the thermodynamic potential E. There is more to these

definitions than just attaching labels to things. In the first place, the natural variables are

the ones that are held constant in order to specify the type of system or process for which

the thermodynamic potential E takes on a minimum value at equilibrium. Second, the

derivatives of E relative to its natural variables are physically significant properties. One

of these properties is the chemical potential, defined by (4.102). Others are:

∂E

∂S

V ,n

i

=T ;

∂

2

E

∂S

2

V , n

i

=

∂T

∂S

V , n

i

=

T

C

V

(4.103)

∂E

∂V

S, n

i

=−P ;

∂

2

E

∂V

2

S, n

i

=−

∂P

∂V

S, n

i

=−

1

V β

S

. (4.104)

If we know the fundamental equation for a system, E = E(S,V , n

i

) then we can know

its thermodynamic state by using (4.102), (4.103) and (4.104) to calculate its pressure and

its temperature, in addition to the chemical potentials of its chemical components. In the

planetary sciences this result is much more than a clever-sounding mathematical gimmick.

In general, we cannot measure intensive variables such as pressure and temperature in deep

planetary interiors by dropping instruments into holes. The fundamental equation for the

thermodynamic potential suggests that there may be alternative ways of doing this.