Cornwall M. The Undermining of Austria-Hungary: The Battle for Hearts and Minds

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

264 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

overloaded with information. It could accumulate data effectively, but it was

weak in the area of sifting and analyzing, and often neglected to build upon

knowledge from previous reports. Perhaps this was quite understandable in

view of the vast territory which it was trying to monitor, not to mention the

accelerating course of events which might well be observed but increasingly

could not be acted upon.

It would

be wrong, however, to suggest that the Austrians' view of enemy

propaganda was wholly speculative or based on unsubstantiated reports. From

the theatre where the main campaign was actually being waged, the Italian

Front, there was indeed material evidence available. It was not only increas-

ingly sophisticated,

but was slowly finding its way into the interior of the

Monarchy, thereby giving some substance to the paranoia mentioned above.

In the spring months, Austria's military commanders in the south-west had

been well aware from the Italian press that their enemy was about to launch

`counter-propaganda'; they began to monitor the signs of an emerging Czecho-

slovak Legion

as well as an upsurge in leaflet distribution. Not surprisingly, it

was from late April that the commanders began to register a striking increase

both in enemy patrols and manifestos. One division over a month found 5000

leaflets of 30 different types,

27

while the number collected and sent to higher

authorities by the lst corps command doubled from 11 813 in May to 20 624 in

June. It is a measure of the perceived danger that such precise figures exist at

all.

28

There was also a clear change in content and language in comparison to

the badly translated and amateurish manifestos issued in the spring; they were

now increasingly orientated towards the Slav nationalities in skilfully phrased

language. As the 10AK noted in its propaganda report for June:

For the

first time the Italians have thrown out a kind of propaganda-news-

paper in several languages: Czech, Polish, Croat and Romanian. The leaflets,

of which those in the same language are numbered consecutively, are gram-

matically and

stylistically accurate, sometimes very suggestively composed,

and betray an intimate knowledge of the views and emotions of the indi-

vidual Slav

peoples of the Monarchy. This proves that Italian counter-pro-

paganda is now directed by clever experts from one or more centres, with

Austro-Hungarian deserters at their disposal.

29

The alarm which this provoked in the war zone was equalled whenever one of

the manifestos was discovered in the interior. This could occur through direct

or indirect means, but the impact was the same, suggesting that insidious

enemy propaganda was managing to send a range of couriers into the heart of

the Empire. In the south of the Monarchy for instance, General Sarkotic

Â

, who

governed Bosnia-Hercegovina and Dalmatia, was always convinced that Yugo-

slav agitation

in `his' territory was a largely external phenomenon, fomented by

Austria-Hungary on the Defensive 265

the Entente. He had offered this as a prime reason for mutinies at Cattaro and

Mostar in February; and when Italian planes proceeded to shower Dalmatia

with leaflets from the Cattaro ring-leaders it simply confirmed for him that a

foreign stimulus was `revolutionizing the Balkans'.

30

In June, much more of a

stir was caused when planes of the Italian 87th squadron made propaganda

flights over both Ljubljana and Zagreb. Carefully instructed by Ugo Ojetti, the

pilots flew low over the cities and distributed three types of leaflet in Croat, two

of which were `signed' by Ante Trumbic

Â

. In one of them, Trumbic

Â

addressed the

civilians as `Yugoslavs!' and assured them that

Our cause

is going very well. If anything should happen which you cannot

at first properly understand, you can be absolutely sure that our cause is a

vital question for all our allies. We are now on the best of terms with Italy.

All the Allies have completely given up the idea that Austria can reorganize

and separate itself from Germany. All are convinced that Austria cannot

exist after the war . . . The behaviour of Emperor Karl removes the last

vestige of any obligation towards the state and dynasty, and imposes an

absolute and unconditional duty on you to fight against such a solution

of our question .. .

Everyone must

do all they can so that we achieve our freedom and unity

... FIGHT FEARLESSLY AND ACTIVELY WITH ALL YOUR MIGHT

AGAINST `MITTELEUROPE' TO RESURRECT A FREE `YUGOSLAVIA'.

31

In another leaflet he gave proof of Italian sincerity by naming Jambris

Ï

ak,

Kujundz

Ï

ic

Â

and other members of the Yugoslav Committee who were now

permanently stationed in Italy.

32

The propaganda flights drew together a curi-

ous audience

below who waved handkerchiefs at the pilots while they in turn

took photographs of the distribution. The flights also drew a sharp response

from the local press and acted as something of a touchstone for loyalty to the

Habsburgs. One Zagreb daily newspaper mischeviously observed that the aero-

planes had

been `neither German nor enemy'.

33

By this time domestic Yugoslav agitation was fast falling outside the control

of the authorities in Slovene and Croat regions of the Monarchy. The Slovene

clerical leader, Monsignor Anton Koros

Ï

ec, was touring southern Slav areas and

speaking to mass-rallies in favour of Yugoslav unity and independence, much

to the exasperation of his rival Ivan S

Ï

us

Ï

ters

Ï

ic

Â

who was head of the Carniolan

provincial Diet and fiercely pro-Habsburg. After the propaganda flight over

Ljubljana, S

Ï

us

Ï

ters

Ï

ic

Â

's mouthpiece, Resnica, launched a virulent attack upon

Trumbic

Â

; it claimed that he was appealing to Slovenes `just like Dr Koros

Ï

ec'

and that the Allies had to be hard up if they needed his help during the Austrian

offensive. The paper then turned upon Jambris

Ï

ak, Kujundz

Ï

ic

Â

and others whose

names had been publicized:

266 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

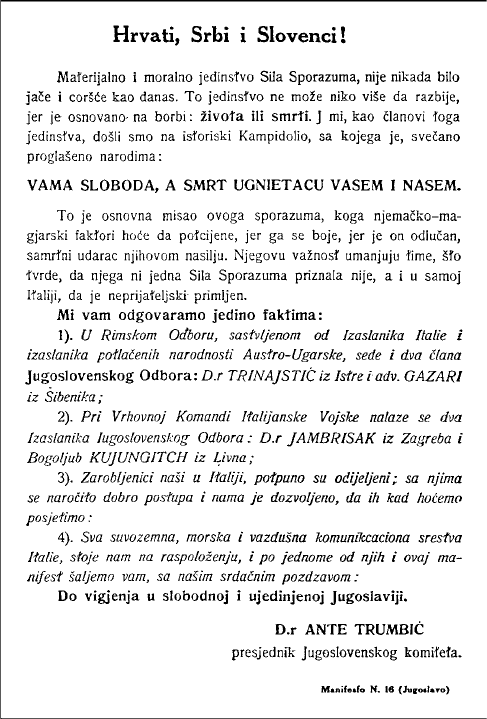

Illustration 7.1 Manifesto 16: Trumbic

Â

announces to Zagreb and Ljubljana that Italian±

Yugoslav relations are excellent (KA)

These then are the traitors who bear the guilt for so much spilt blood!

Dr Trumbic

Â

gives us proof in his manifestos of who it is who is prolonging

the war for us and on whom the Entente are relying in the last resort. Since

they cannot defeat us militarily they hope to be saved by Dr Trumbic

Â

and

his Yugoslavs. Dr Trumbic

Â

is barred for all time from returning home; only

with Allied troops can he set foot in his homeland again. But there is little

chance of that happening and therefore he is trying to involve as many

unfortunate associates as possible in his fate. He has however opened our

people's eyes to such agitation.

34

Austria-Hungary on the Defensive 267

To re-emphasize this stance, on 19 June S

Ï

us

Ï

ters

Ï

ic

Â

persuaded the small Car-

niolan provincial

council (the executive organ of the Diet which had not met

during the war) to ordain that regional parish councils should publicly con-

demn Trumbic

Â

's

behaviour. Koros

Ï

ec in turn told the editor of Slovenec, his

radical mouthpiece, to instruct parish councils through its columns either to

ignore S

Ï

us

Ï

ters

Ï

ic

Â

's order, or to stand resolutely by the May Declaration of 1917

which by now euphemistically implied a commitment to Yugoslav independ-

ence, the

same ideal as Trumbic

Â

's. As a result the parish councils at first

ignored S

Ï

us

Ï

ters

Ï

ic

Â

. Then, when on 3 July the Carniolan council issued a second

circular, the 164 parish councils who replied expressed their disapproval of

Trumbic

Â

's propaganda, but also proceeded to reaffirm the May Declaration,

thereby subtly invalidating their own disapproval.

35

The parish councils' defi-

ance was

backed up the mayor of Ljubljana, Ivan Tavc

Ï

ar, who announced that

S

Ï

us

Ï

ters

Ï

ic

Â

's order was a violation of local government autonomy in Carniola.

36

S

Ï

us

Ï

ters

Ï

ic

Â

's stance had therefore backfired, revealing the weakness of his own

position while lending increased publicity to the fact that Allied propaganda

was actually in tune with Koros

Ï

ec's native movement. It was just one example

of how Italy's campaign was beginning to act as a catalyst upon unrest in the

Monarchy. The propagandists themselves were delighted with what they knew

of the response, Steed noting that `we have at least this proof that our propa-

ganda has

had the effect of angering the enemy'.

37

It gave them confidence to

aim at propaganda targets further afield, such as Vienna itself.

By the

summer months in any case Padua's manifestos, so evident in the war

zone, were penetrating into the interior by indirect means which the propa-

gandists could

hardly imagine. Soldiers on leave, or hospital patients, were

taking home manifestos which they were supposed to have surrendered in

the war zone. The leaflets began to turn up not only in Innsbruck and Graz,

or in regions near to Zagreb or Ljubljana, but also as far afield as St Po

È

lten,

Bratislava, Turnov in northern Bohemia, and even Krako

Â

w and Lublin.

38

This

might seem an academic point, but for the authorities it was not. Each discov-

ery was

treated with reverence, necessitating a scrupulous investigation and the

eventual dispatch of the leaflet to Ronge's Evidenzbu

È

ro

in Vienna. For example,

in mid-September in Kolozsva

Â

r a Lieutenant Erwin Ridley came across three

soldiers who were surreptitiously reading one of Padua's newssheets; it had, he

was told, been smuggled into Transylvania by one of them from the war zone.

The three men subsequently disappeared, whereupon the local battalion com-

mander, lambasting

Ridley for not having arrested them on the spot, ordered

an immediate examination of all the battalion's correspondence and all the

soldiers' belongings.

39

Such a procedure was not unusual whenever a single

manifesto was uncovered in the hinterland, whether it stemmed from Italian

or Bolshevik or Polish revolutionary sources. In each case, the security forces

were reminded, it was their duty to root out what Arz termed the `dangerous

268 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

mischief' of smuggled leaflets by meticulous enquiries.

40

This sometimes

assumed absurd proportions. On 10 June, for instance, a hospital in southern

Bohemia sent to the military command at Prague two Czech leaflets which had

been discovered on a patient who had been transported from the Italian Front.

A lengthy investigation and correspondence ensued which lasted over two

months. The authorities tracked the guilty patient down from Vienna to

Sarajevo to Dalmatia, only to discover that he had simply been curious and, as

a Croat, had not been able to make much sense of the dangerous manifestos.

41

It cannot be denied that the military were doing all they could to root out

the evidence of `enemy propaganda'. Ronge himself on one occasion observed

that Flugschriften might be the prime danger in this regard. Only later would he

write that leaflets had simply been a symptom of what was fundamentally

wrong in the Monarchy; the real disease, the deeper affliction, had needed

serious treatment but had been left unattended by the government.

42

He

might have added that leaflets or any other form of `enemy propaganda',

viewed as so pervasive by the authorities in 1918, could only cause harm if

they had a diseased environment in which to flourish.

7.2 The Feindespropaganda-Abwehrstelle

It was a consistent complaint by the Austro-Hungarian military in the last year

of war that, while they were doing all they could to eliminate enemy propa-

ganda, the

political authorities in the Empire were failing to match their efforts.

Subversive ideas were being left unchecked to circulate in the hinterland. How

could the military protect the armed forces at the front if their morale was

constantly under threat from contact with social and political unrest in the

interior? This was not, of course, a new consideration: the military had blamed

domestic conditions for the notorious Czech desertions of 1915, and in the

summer of 1917 Conrad had concluded that lax discipline on the Italian Front

was directly caused by lax discipline or inefficiency in the hinterland. What was

new in 1918 was the degree of social and nationalist agitation and the fact that

the domestic authorities seemed increasingly powerless to control it. Stimu-

lated by

the food crisis and war-weariness, a `secondary mobilization' was now

taking place among broad swathes of the population. It was not, however, the

kind of resuscitation witnessed in Italy after Caporetto. In Austria-Hungary,

rather than being a movement to support the Empire at a time of crisis, it had a

diverse nationalist, pacifist and social agenda: it was essentially a `counter-

mobilization'. The

Habsburg military could note with alarm that this move-

ment in

the interior increasingly echoed the work of ubiquitous `enemy

propaganda' stemming from outside the frontiers. In this situation the

armed forces seemed to be placed in a vice, between two aspects of the

same merging phenomenon. The AOK had the impossible task not simply of

Austria-Hungary on the Defensive 269

keeping the troops immune from subversive ideas, but of sustaining and

strengthening their commitment to the Habsburg state during a fourth year

of total war.

From January

1918 it was in the context of all the perceived dangers, from

home and abroad, that the AOK took counter-measures to try to tighten

discipline and protect troop morale. At the front precautions against deser-

tion were

increased. The men were reminded that all deserters would be

court martialled, their property would be confiscated, state benefits to their fam-

ilies would

be halted, and they could expect no amnesty after the war. As fur-

ther deterrents

to insubordination, Arz managed to persuade the Emperor to

reinstate those punishments he had abolished in mid-1917, while persistent

offenders would henceforth be grouped into `disciplinary units' for three

months and used for hard labour near the front line.

43

Hand-in-hand with

these guidelines, the officers were to be vigilant in seeking out all dangers

associated with `enemy propaganda'. Because of evidence that subversive leaf-

lets were

being circulated in the hinterland, the AOK ordered a reorganization

for the whole Empire of the ambulante Reisekontrollen, the military personnel

whose duty was to inspect travellers and maintain discipline on the railways.

On 10 March the same fears led Baden to order a sudden search of all soldiers'

belongings in the war zones. The result was largely negative at this time, but as

Arz reminded his subordinates on 27 May, this left no room for complacency.

Since `Northcliffe Propaganda' and `social-revolutionary agitation' were at

work, the troops should be observed constantly and inconspicuously; their

luggage should be searched if they were going on leave, they should be

reminded that it was a treasonable offence to be in possession of any propa-

ganda leaflets,

and if any `treason' was uncovered there should be an immediate

and sudden examination of the unit's effects.

44

If many of these orders were chiefly applicable to the Italian Front, where

over two-thirds of the army were now stationed, in the East the AOK was

making special arrangements for dealing with an influx of Bolshevik propa-

ganda through

the dissolving Eastern Front. There it was not so much a ques-

tion of

smuggled leaflets, but a question of how to treat the thousands of

ex-prisoners, so-called `homecomers', who, in the wake of the Treaty of Brest-

Litovsk, were flooding back into the Monarchy. Already in early 1917 Austrian

military Intelligence had decided that instead of receiving a jubilant welcome,

all homecomers would have to undergo a strict examination to assess their

behaviour in Russian captivity and ensure that they had not been tainted by

Bolshevism or other poisons. Thus, from early 1918 they were coldly `processed'

by the Austrian authorities, kept in 53 special camps under miserable condi-

tions, and

even when judged `reliable' were usually conceded only a few weeks

leave before having to rejoin units at the front. By June 1918 over 500 000

had entered the Monarchy and almost 2000 had been dispatched again to the

270 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

front. Max Ronge would judge later that the apparatus established to deal

with the homecomers had been a `too widely meshed sieve' to counter

Bolshevism (particularly since the necessary Intelligence personnel were

lacking). In fact, it was the very nature of the apparatus which bred much of

the homecomers' disillusionment with a homeland where they were `treated

just like cattle'. Many proceeded to desert when on leave. Others who rejoined

their units constituted small insubordinate cores which were largely respons-

ible for

six major rebellions in the hinterland in May 1918.

45

It was a prime

example of what could happen if the authorities were insensitive to the outlook

of `demobilized' soldiers. By putting the emphasis on discipline and security,

rather than any positive educational or human agenda, the very dangers which

Baden most feared were brought to life and multiplied.

Yet Austria-Hungary's

military leaders were certainly aware that simple

defensive measures were not likely to provide adequate protection from enemy

propaganda. As the Minister of War had noted in a letter sent to all military com-

mands in

early February, the Russian army had disintegrated precisely because

in late 1917 its `educational organs' had been insufficiently equipped to with-

stand revolutionary

propaganda.

46

In other words, sharp vigilance and discipline

had to be accompanied by well-organized `patriotic instruction' (VaterlaÈndischer

Unterricht)

on behalf of the Habsburg cause. Until 1918, although the KPQ had

made some small efforts, it was chiefly the military pastorate in the Austro-

Hungarian army who had undertaken this task. Some military chaplains un-

doubtedly made

no impact amid the horrors of the trenches (they merit no

mention in Ljudevit Pivko's memoirs for instance). A few may well have

resembled the disreputable Otto Katz, the coarse and drunken padre in Jaroslav

Has

Ï

ek's novel The Good Soldier S

Ï

vejk, who was based on a real individual.

But others were certainly viewed as a valuable asset by the military hierarchy

because of their frequent visits to the trenches, sharing the troops' hopes and

fears, and awakening `their sense of duty toward the monarch and the father-

land with

appropriate lessons'.

47

At first the AOK simply envisaged an intensification of such work by the

immediate officer commanding each unit. Through informal conversation he

would enquire into a man's background and private life, `in order to gain

insight into the psyche, mentality and level of intelligence of his subordinates,

to encourage the man's trust in the officer [and at the same time] discover the

destructive elements, socialists, anti-militarists, etc., among his subordinates

and paralyze their damaging influence upon the other men'. The soldiers would

be reminded of their military oath, taught about the true causes of the war (how

Italy, the Monarchy's 30-year ally, had stabbed it in the back) and instructed in

a way to bolster Staatsgedanken, or ideas of state loyalty: how after success on

the Eastern Front the Empire could feel very optimistic about the future,

determined to continue fighting until an honourable peace was concluded.

Austria-Hungary on the Defensive 271

While many of these forthright ideas were the same as those contained in

Austria's propaganda against the Italian army, the officers were told that that

was a distinctly separate activity, the prerogative of the Nachrichtentruppen, who

alone were responsible for trying to influence the enemy.

48

As support for the new `instruction' in the Austrian ranks, the KPQ moved to

step up its own activity. In February 1918, a special `Front propaganda section'

was created at the KPQ under Lt-Colonel Arthur von Zoglauer who began

to organize patriotic lectures in the war zone. In addition, the KPQ was to be

responsible for producing a weekly journal with articles on topical subjects. The

first editions appeared on 7 March, entitled Heimat in German and U

È

zenet

in

Hungarian, and a very limited number were dispatched to the Italian Front to

be presented to troops as a `privately published' newspaper. From the start there

were hints of the difficulties to come. While the German and Hungarian edi-

tions were

easily produced, it proved impossible to find writers or typesetters for

journals in the other languages of the Monarchy; as a result Croat and Slovene

editions, though planned, were never to see the light of day. Then there was the

issue of content. In the third edition of Heimat, for example, a long piece

extolled the virtues of being an Austrian, claiming that Austrians with their

traditions of empire, racial mixture and Gemu

È

tlichkeit,

were called upon to

rescue the soul of Europe.

49

Ideally, such a piece would simply be reproduced

in any Hungarian or Czech editions, but to do so was problematic because of

the increasingly heterogeneous outlook of the armed forces. The AOK was faced

with the dilemma of wishing to propagate a united Austrian patriotic message

while realizing that, if it was to be successful, each nationality would also

require a different slant to match its own viewpoint. This fundamental issue

was resolved unsatisfactorily, again because (ironic in a multinational empire),

the personnel could not be found to act as editors or writers for different

national editions. The AOK might want uniformity with a `national twist' in

some articles. Instead the Czech edition, Domov, had to remain as a simple

translation of Heimat, something which was hardly likely to endear itself to the

most sceptical nationality in the Monarchy.

50

Not surprisingly, none of the

journals gained many individual subscribers so that, by the autumn of 1918,

Baden would decide to send hundreds of free copies out to military positions. It

is important to note that, in contrast to other belligerent armies, the `news

vacuum' at the front does not appear to have been filled by unofficial `trench

newspapers' composed at a grass-roots level. Rather it was the Empire's nation-

alist press,

backed up by Italy's manifestos, which could fill the gap for those

who wanted `real news', propagating information in a far more enticing way

than anything the Austrian authorities could offer.

51

The High Command's moves, however, were only the start for a programme

of patriotic instruction which it envisaged on a far grander scale. On 14 March,

Arz announced the creation of a special organization to control education in

272 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

the armed forces. It seems most likely that he was encouraged to do so by the

example of Germany, where patriotic instruction had already begun in the

summer of 1917. The AOK always seem to have believed that Germany's

apparatus was functioning excellently, and it accordingly took Germany as

something of a model for Austria-Hungary, sending a representative to Berlin

in June 1918 to consult more closely.

52

In fact, as we will see, patriotic instruc-

tion in

the Monarchy would be a strictly military affair, and ironically far less of

a `political offensive' than was possible in the military-run German Reich.

53

But

if Germany was one model in the spring of 1918, the Monarchy had another

model in Italy where, in the wake of Caporetto and in the face of Austrian

propaganda, a galvanizing of forces was known to be taking place. In the words

of the KPQ report for January, `no country demonstrates like Italy how modern

warfare can even offset defeat and how national consciousness can be regener-

ated by

the power of propaganda'.

54

Here indeed the two enemies were taking

note of each other's skill with offensive and defensive `propaganda'. On the

Italian side there were loud calls for Italy to follow the example of Austria's

offensive campaign, while among the Austrian commanders it was Italy's

defensive educational measures which were being particularly noted and

recommended.

55

Similarly, from the Eastern Front, too, the AOK heard voices which pressed

for VaterlaÈndischer Unterricht. Especially influential may have been a personal

letter from Dus

Ï

an Petrovic

Â

, chief of staff of the 54SchD, to a friend at the AOK.

Writing from Ukraine, from the new `peaceful front' as he called it, Petrovic

Â

drew attention to continued Russian attempts to fraternize with Austrians and

the rising number of Austrian desertions. He enclosed an order from his own

commander, which called for more pastoral care and patriotic instruction in

the ranks, and he himself pressed the AOK to respond with some kind of

`obligatory patriotic instruction' so that the men could be moulded by more

than blind obedience to discipline.

56

The precise outcome of Petrovic

Â

's plea is

not known, but one direct result was that he was appointed as deputy-head of

the AOK's organization for patriotic instruction. The new organization thus was

springing to life because the Russians had set a woeful example, while the

Germans and Italians were already suggesting that new measures were required

to protect the armed forces during a fourth year of war.

When on

14 March the organization was announced (to the military auth-

orities, not

publicly), the reasons which Arz gave for the new body reflected

clearly the AOK's perception and prioritization of tangible dangers. First, it was

needed to combat those elements, buoyed by war-weariness, which were threat-

ening Austria-Hungary

politically and socially from within. Second, it would

counter Bolshevism, which despite its frightening characteristics could still be

tempting to the masses. Third, it would fight `propaganda stemming from the

enemy' since `Northcliffe's appointment as English ``Propaganda minister''

Austria-Hungary on the Defensive 273

shows most clearly what hopes our enemy sets in its publicity work'.

57

The

three inter-linked dangers were encapsulated in the title of the new organiza-

tion, the

`Enemy Propaganda Defence Agency' [FAst ± Feindespropaganda-

Abwehrstelle]. This suggested, in tune with AOK thinking or at least with

what the ranks needed to think, that the danger was essentially foreign, alien

to both army and Empire, even if certain subversive agents within might be in

league with `enemy propagandists'.

The head

of the FAst was to be an invalid who worked at the War Archives,

Egon Freiherr von Waldsta

È

tten (brother of the deputy Chief of Staff). On 20

March, at the FAst inaugural meeting at the War Ministry, Waldsta

È

tten set out

for other military authorities the AOK's plans for patriotic instruction. The first

task was, along the lines of Germany's example, to organize teacher-training

courses for propaganda officers. Separate courses would be run in Vienna and

Budapest (the latter in July to cater for Hungarian Honve

Â

d units), and those

who passed through them would then act as FA instructors amongst military

units in the field or hinterland so that a vast FA network would evolve through-

out the

Monarchy. Already at this meeting there were those who pointed out

possible problems. Zoglauer, the head of the KPQ's new `Front propaganda

section', spoke pessimistically already about his own experience in organizing

lectures at the front. It had proved very difficult to condense the material, since

`a lecture could not last longer than 30 minutes, or with slides 45 minutes,

without tiring the audience'. Zoglauer's fellow KPQ delegate, Colonel Reich,

broached a more intractable problem, that of unity of ideas in the curriculum.

He observed, however, that it was unity of `spirit' rather than `form' which

was vital in the education: the correct tone would still have to be found for

each nationality while at the same time ensuring a general unity of purpose.

Although it appears that those present shared Reich's optimism that this bal-

ance could

be achieved, it was to be a major dilemma which the FAst would

never master successfully.

58

In the following weeks Waldsta

È

tten began to pester the military authorities

with a range of issues which seemed to be within his new jurisdiction. He made

suggestions to Baden about how officers should behave at the front. He warned

the War Ministry about subversives in the interior: subversive newspapers, but

also agitators like the satirist Karl Kraus who, at a recent public meeting in

Vienna, in the presence of soldiers, had criticized Germany's use of gas on the

Western Front, referring to the `chlorious' [chlorreichen] rather than `glorious'

offensive.

59

But Waldsta

È

tten and his deputy Petrovic

Â

were, of course, above all

concerned at this time with establishing their new machinery. It would be

centred upon an office in the KA (Stiftgasse 2, Vienna), reflecting that institu-

tion's modest role in domestic propaganda since the start of the war. To the

FAst were appointed about a dozen staff. They included most notably Professor

Ernst Keil, the founder of the satirical journal Die Muskete, who had good