Cornwall M. The Undermining of Austria-Hungary: The Battle for Hearts and Minds

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

124 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

had repositioned three `pawns' of his own foreign service: Baron Silvio a Prato

at Zurich, Giovanni Giovannazzi at Zernetz on the Austrian±Swiss border, and

the fearless Luisa Zeni at the key railway junction of Innsbruck. By September

all had been exposed and fled to Italy (Giovannazzi vainly trying to fool the

Swiss authorities by swallowing his invisible ink as if it were medicine).

40

Marchetti therefore started again, this time more successfully. By the summer

Ufficio I had established its own CS Intelligence centre in Berne, but Marchetti

was always highly sceptical of its competence, describing it once as `stunted

with rickets';

41

it made him all the more determined to preserve his own

`foreign empire'. In mid-September he dispatched to Zurich, as a replacement

for Baron a Prato (who had first fled to France), four `Trentini' who had already

distinguished themselves: Artemio Ramponi, Clemente Albertini, and Luigi

Grandi and Luigi Granello (both former professors in Trieste, the latter espe-

cially knowledgeable

about Austria's domestic affairs). Working undercover, as

supposed employees of a timber merchant, their job was to scrutinize the

Austro-Hungarian press, particularly Tyrolian papers; to make new contacts

with Austrian citizens who could be useful for espionage; and to strengthen

ties with Czech, Polish or Yugoslav e

Â

migre

Â

groups whom Marchetti was already

assessing as valuable instruments for the future.

42

His `Swiss centre', using the

CS Intelligence office at Berne as something of a shield, was to remain largely

inviolate until 1918, and some of the agents then continued to act as valuable

lynchpins in Italy's new propaganda campaign.

Marchetti, however,

always had an additional string to his bow through

being able to re-establish some agents in Austria itself. Through the contacts

of Mario Mengoni, a former hotelier on Lake Garda, Marchetti acquired a

nucleus of reliable informers. One was a greengrocer who travelled regularly

between Zurich and the Tyrol and hid information in pellets in the base of his

pipe. Another was a Swiss industrialist who visited Besenello every so often to

inspect a silk factory (and anything else on the way).

43

But the key agent was

Mansueto Zanon, an Italian soldier in the Austrian army at Innsbruck who

could observe all troops movements on railways into the Tyrol, while also at

times having access to high-level military discussions at Bolzano [Bozen]. With

the aid of a Czech friend who worked on the Austrian railways, Zanon was able

to supply timely and accurate information to Mengoni in Switzerland, the

methods of communication becoming ever more eccentric, from writing in

invisible ink to concealing thin strips of paper within candles or cough

44

sweets. This notwithstanding, Zanon remained until the very end of the war

Marchetti's special confidant, an agent who on many occasions made reliable

predictions about Austrian intentions, not least about the ill-fated Trentino

offensive of May 1916. Marchetti himself would later express his feelings of

`reverence and admiration' for Zanon, his `best informer'. And it was undoubt-

edly largely

due to the latter's reports that one British Intelligence chief, on

The Seeds of Italy's Campaign 125

arriving in Italy in late 1917, singled out 1st army Intelligence for particular

commendation: `[It] had long before organized a special local service which

extended its activities throughout the southern Tyrol with such success that the

Intelligence of this army was always well supplied with information pertaining

to this portion of the theatre.'

45

Marchetti's foreign network was proof to some extent of how middle-class

Italian irredentist sentiment in the Trentino could be effectively exploited and

harnessed to undermine the Habsburg Empire. At the front too, from the first

months of the war, `Trentini' were employed by military Intelligence to analyze

the enemy situation opposite, or ± in the case of Cesare Battisti himself in 1916

± to produce detailed maps and reports about the terrain and military defences

of the southern Tyrol.

46

In the 1st army, which again appears to have been the

most inventive in its techniques, front-line Intelligence fell into the hands of

Cesare Pettorelli Finzi (since Marchetti preferred to stay in Brescia and concen-

trate on

his espionage network). It became the ideal partnership, with March-

etti and

Finzi acting as a control upon each other's sources of information. Finzi

had at first been drafted into the Intelligence office at Verona as an interpreter.

He was a former military attache

Â

in Budapest, spoke German and Hungarian

and was married to a Slav. Despite a prejudice against Croats, who had allegedly

maltreated his grandfather during Radetsky's campaign in 1849, his perception

of the enemy forces far exceeded in sophistication that of many compatriots

who tended to group all their opponents together as `Austrians'.

47

When he

took over the Verona office in August 1915, Finzi still seems to have rated

highly the tradition and experience of the Habsburg forces, backed by a `state

organism [with] foundations which appear to be very solid, despite so many

races, so many languages, the different mentalities, the divergent aspirations'.

48

It was only perhaps in early 1916 that Finzi adjusted his horizons, realizing

that Italian Intelligence must in its essence begin to reflect the mosaic qualities

of the Austro-Hungarian army. For in the months prior to Austria's Trentino

offensive, many more deserters, `startled birds' at the onset of a whirlwind as

Finzi describes them, began to cross to the Italian lines. And these, besides

the usual `Trentini', were chiefly of Czech nationality, including some Czech

reserve officers who clearly lacked the type of imperial loyalty ingrained in the

psyche of the old career officers.

49

Finzi had been collecting prisoners and

deserters together at Verona's Procolo fortress, a building which ironically

had been built by the Austrians in the 1840s as a safeguard against Italian

rebels. He now began to use three intelligent Czech officer-deserters as `pigeons'

(spies) within the fortress to weed out information from incoming prisoners.

50

It was a technique which was to be adopted by other Intelligence heads, was

peculiar to the Italian army, and was subsequently viewed somewhat critically

by British military Intelligence who felt that it produced information which

was `detached and fragmentary in its character'.

51

It meant, however, that Slav

126 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

deserters from the Austrian army were increasingly employed for Intelligence

purposes which had formerly been restricted to Italians or `Trentini'. By 1917,

on the basis of their success, Finzi was extending his techniques, dividing up

prisoners in the Procolo fortress according to nationality and slipping into their

`cages' reliable Czech agents, who posed as fellow-prisoners and `squeezed and

sucked, as from a lemon, everything which the prisoners could have seen' or

experienced.

52

It was a short step from here to employing Czech deserters in

other fields: to intercept enemy telephone conversations, to interpret or com-

pose Intelligence

reports, or even to engage in some propaganda work to

influence the morale of their former compatriots. In very exceptional circum-

stances, these

tasks might even be allotted to Slavs of other nationalities; by the

early summer Finzi was using one Croat deserter-officer, Mate Nikolic

Â

from

southern Dalmatia, in 1st army Intelligence.

While Finzi

and Marchetti acted as torch-bearers, notably in their trust of

Czech deserters, their outlook was in part an understandable derivative from

regular contact with the enemy. From 1916, Italian military Intelligence was

certainly aware that among the enemy forces, it was soldiers of Czech nation-

ality who

were sometimes more likely to be an unreliable element. This was

clear from some notable officer desertions on the Tyrolian front, but it was also

the case in the Giulian sector, on the river Isonzo. There, the Intelligence

officers were perhaps less enlightened than in the lst army, but at least by the

summer of 1916 the Italians were beginning to use some Czech officer deserters

as interpreters or informers before sending them off to the prison camps.

For example, Va

Â

clav Pa

Â

n aided 2nd army Intelligence for two months, while

Jaromõ

Â

r Vondra

Â

c

Ï

ek, a company commander who deserted in mid-August,

brought over plans of his sector which enabled the Italians to attack and seize

a key point; he was employed at 3rd army Intelligence for three months before

being dispatched to the officer-deserter camp at Bibbiena.

53

But it was the reserve officer Frantis

Ï

ek Hlava

Â

c

Ï

ek, a deserter who later played a

leading role in establishing the Czech Legion in Italy, who was the most

glittering prize for Italian Intelligence on the Isonzo.

54

As a civilian, Hlava

Â

c

Ï

ek

had worked for the Prague chamber of commerce, had travelled extensively

abroad and had a number of contacts in Italy (his wife's cousin was the painter

Oskar Bra

Â

zda). After settling his domestic affairs when on leave in Prague in July

1916, he managed on 11 August to desert to the Italians at Salcano during the

battle for Gorizia, giving them valuable information about enemy artillery.

More importantly, he brought with him detailed plans for an offensive in a

crucial sector (of Auzza-Descla), which might enable Italy to capture the Bain-

sizza plateau.

Although encountering much scepticism and suspicion, Hlava

Â

c

Ï

ek

was interviewed by some sympathetic Intelligence officers (including Giuseppe

Lazzarini, a friend of Bissolati) and as a result was eventually able to expound

his views to the CS at Udine. This did not prevent his dispatch to the camp at

The Seeds of Italy's Campaign 127

Bibbiena in October. But in April 1917, possibly at the insistence of General

Pietro Badoglio, chief of staff of the 2nd army, Hlava

Â

c

Ï

ek was recalled to the

latter's headquarters at Cormons and ordered to elaborate his plan in minute

detail.

According to

Czech sources, although the plan was never fully put into

practice but remained in May a local operation, that in itself achieved remark-

able success

because of the response in the Austrian camp. At Bodrez-Loga on

the northern edge of the Bainsizza plateau, almost a whole battalion of Czechs

declined to fight and deserted to the Italians. If such behaviour was not a

normal occurrence, despite the few legendary cases on the Eastern Front, on

the Italian Front it undoubtedly set a precedent for possible Czech behaviour,

while among the Italian military it `made Pauls out of some of the Sauls'. When

Hlava

Ï

ek subsequently met Major Dupont, the head of 2nd army Intelligence,

Â

c

and

General Capello, the 2nd army commander, he was given a much warmer

reception (Capello going so far as to shake his hand) and was able to exploit his

new leverage. While the Italians were now envisaging a full Bainsizza offensive,

Â

c

Hlava

Ï

ek became the first Czech prisoner to be liberated in Italy. He was

allowed to travel to Rome to work briefly in Vesely

Â

's bureau, before returning

in August to Cormons where in Italian uniform he interrogated prisoners and

helped Dupont to construct a comprehensive picture of the Austrian line-up.

This activity for the Italians in the summer of 1917 was to earn him the military

cross. In turn, Hlava

Â

c

Ï

ek had himself significantly advanced the Czech cause,

spreading Czech literature in military circles, making valuable new contacts for

the future (not least Dupont and Badoglio), and indicating by his own example

how the Italian army might adopt the nationality principle for military

advantage. His extensive and growing influence would later earn him a quip

from Czech legionaries, that `God in heaven is the first God, but Hlava

Â

c

Ï

ek the

second God'.

55

It was through using Czech deserters in this way that Italian military Intelli-

gence also

began to employ them for the purposes of propaganda. Front pro-

paganda was

a task naturally assigned to the Intelligence officers since they

were increasingly aware that by spreading manifestos they could provoke more

desertions, and thereby gain more information about the enemy. Gradually,

they would also realize the need for these manifestos to be trimmed to suit the

mood and character of the Austro-Hungarian forces, but a sophisticated opera-

tion would

only begin in the last year of the war. It seems to have been in June

1916, in the wake of Austria's Trentino offensive, that the Italians first took up

the propaganda weapon to any degree. A few months earlier at Easter some

manifestos had been distributed which gave basic information about `Entente

successes',

56

but the CS otherwise appears to have hesitated because of Austrian

threats that enemy pilots who spread treasonable leaflets would be executed.

57

However, after the failed offensive, when the Austrians had still spread leaflets

128 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

glorifying their `successes', 1st army Intelligence in revenge sent back brightly

coloured manifestos which depicted the Austrian attack as a broken bottle and

also proceeded to revel in Austria's retreat in the East during the Brusilov

offensive.

58

These efforts were continued in August when the Italian capture

of Gorizia was broadcast to the enemy, together with news of Russian advances

in the Caucasus, Anglo-French advances on the Somme and the resurrection of

the Serbian army in the Balkans.

59

Most of the leaflets at this time and in the following year contained a text in

several languages, translated (often badly) by deserters, and they were not

usually tailored specifically towards any particular nationality. They aimed to

illustrate above all, firstly the strength and secondly the justice of the Entente

cause, countering Austrian `lies' and exploiting any negative turn in the for-

tunes of

the Central Powers. In March 1917, for instance, leaflets informed the

Austrians that although the Tsar had abdicated, the Russian army was regener-

ating itself

(supposedly under Grand Duke Nicholas);

60

by April, the leaflets

told of the entry into the war of South America and the United States, with

President Wilson determined to crush the `hereditary enemy' with all available

forces.

61

As a result, the Central Powers were now portrayed as the enemies of

`all cultured peoples'. The propaganda at this time was not averse from openly

attacking the `over-ambitious German Kaiser' who had `shocked the whole

world by his most atrocious methods of warfare' and was now seeking to pull

the chains ever tighter around the peoples of Austria-Hungary.

62

Thus Italian

front propaganda was beginning to contain a distinctly moral note, even

though Italy's own professed morality (that it was fighting a `holy national

war') was hardly one which would appeal to all Austro-Hungarian soldiers.

63

Yet the nationality principle slowly began to creep into some manifestos. The

first signs of it were the result of a specific initiative by the Czech e

Â

migre

Â

organization in Paris. In late 1915, when the Slovak aviator and astronomer

Milan S

Ï

tefa

Â

nik had got to know Nicola Brancaccio, he had alerted him to the

possibility of some Czech propaganda on the Italian Front. S

Ï

tefa

Â

nik

then com-

posed a

preliminary manifesto which, although highly emotional and rather

repetitive, had already been distributed over Austrian lines by the turn of the

64

year. The CS was immediately impressed, reporting to Brancaccio that among

Austrian prisoners (and even among Russian POWs working in the Austrian

rear lines) the impact had been `great'; the CS duly requested more texts

which would be printed in Italy with S

Ï

tefa

Â

nik's autograph.

65

Instead of this,

Brancaccio organized a direct approach. S

Ï

tefa

Â

nik,

a pilot in the French

army, was allowed to visit the Italian war zone where he met leading milit-

ary figures

and personally threw out leaflets from his plane over the Austrian

trenches. These manifestos made S

Ï

tefa

Â

nik

a marked man in Austria-Hungary

66

since their text, although signed by the `Czechoslovak Foreign Committee',

clearly revealed the Slovak's own personal role:

The Seeds of Italy's Campaign 129

Slavs! Czechs!

The Germans

and Magyars have declared war on the whole world, for they

want to dominate all nations and specifically to make slaves of us Slavs in

order to have somebody to work for them. Our Russian brother and our

friends, France and England to whom Italy has allied itself, want to crush

this pride and conceit.

The glint

of their victories can be seen on the horizon. In the east our

Russian brothers have halted the Germans and trounced the Turks, in the

south the Serbian army with the help of France and Italy has once again

entered the fight and the intimidated Bulgarians are quaking in the face of

its speedy retaliation, in the west at Verdun the French have struck the

Germans a mortal blow. The days of the Slavs' enemies are numbered. The

victories of the Russians, England, France, Italy, Serbia, Belgium and Portu-

gal, who

have united in this conflict with the Germans and Magyars, signify

the liberation of oppressed peoples, and especially the creation of an inde-

pendent Czechoslovak

state and unification for the Yugoslavs.

You who

are honourable of spirit and have Slav blood in your veins, should

remember that it is your sacred duty to use every circumstance to weaken those

whom you currently serve. Give yourselves up to the Italian army at the first

opportunity, just as whole Czech regiments have already done, voluntarily

and enthusiastically, when the Magyars and Germans sent them against Ser-

bians, Russians

and the French. All those who surrendered were received with

open arms. Thousands of them, instead of hospitality, asked for a sabre and a

rifle and turned against the murderers of the Czechoslovak people.

For don't

forget that the same Magyars and Germans who push you

forward are torturing our national leaders at home, ravaging our cottages,

shooting and hanging old people, women and children, confiscating the

estates of patriots. Do all of you who are Slavs wish to sacrifice your lives for a

contemptible band of criminals who have set as their goal the extermination

of our whole nation? For those of you who continue to fight after this

announcement, may the dishonour and curse of the nation lie on you.

Victory over the Germans and Magyars is certain, and by resisting you are

only prolonging your own suffering.

This message

is sent to you by the leaders of the Czechoslovak nation,

especially Professors Masaryk and Du

È

rich.

67

But Lieutenant Dr Milan S

Ï

tefa

Â

-

nik has

himself come from France to Italy and over your trenches in order

to deliver it to you from his aeroplane. Remember brothers, at these great

historical moments, your national duty, your Czechoslovak homeland, and

our dear people.

68

This manifesto, containing the type of vivid language which would be so

evident in the propaganda of 1918, was, in the words of one authority, `the

130 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

first significant and successful step in Italy on behalf of the Czechoslovak

foreign resistance'.

69

The Czech e

Â

migre

Â

s followed it up during the summer of

1916 by presenting Brancaccio with thousands more leaflets which they hoped

could be distributed.

70

By this time some of the army Intelligence officers were themselves coming

separately to the same conclusion, following a train of thought which derived

naturally from their own experiences as much as from any knowledge of

S

Ï

tefa

Â

nik's initiative. As we have seen, from June 1916 the Italians began to

increase their distribution of manifestos. While most of these dwelt on Italian

or Russian victories, there were some `rare birds' (as Marchetti and Finzi termed

themselves) who now realized that it was the `latent racial malady' which Italy

should be exploiting. As Marchetti was to write so incisively: `the decay had still

not infected the [Austrian] army which, through secular traditions, through the

cementing symbol of the person of the old sovereign, through its iron discip-

line, was

still solid and healthy, materially, morally and politically'.

71

Yet he

had noticed the `first insidious cracks' in the old imperial building. 1st army

Intelligence now became a pioneer in propaganda work, proposing to the CS on

1 August 1916 that propaganda should be intensified and concentrated espe-

cially on

provoking unrest among the various races. In Finzi's words, they were

`seeking to make the sense of nationality resonate, to throw out the seeds of

what could be future discord'. Finzi himself was convinced that this path

should be followed because of his experiences in interrogating prisoners of

various nationalities, and also from discovering that deserters showed such

interest in propaganda leaflets, often carrying them as `passports' for good

treatment in Italy.

72

Indeed, most of the `national' leaflets which Finzi prepared

in the next 12 months were probably simple appeals to desert, sometimes with

a special twist to entice a particular nationality. Many seem to have dwelt on

the comfortable life enjoyed by all Austrian prisoners in Italy, but even in these

unsophisticated messages the Czechs might be reminded that Russia was Italy's

ally, the Romanians and Croats about the Magyar threat, and the Poles about

conditions in Galicia.

73

By the early summer of 1917, although the manifestos continued to be in a

rather stilted language and full of spelling mistakes, one could sense a more

radical tinge which increasingly matched S

Ï

tefa

Â

nik's early efforts. Czechs were

informed about their compatriots fighting in the Russian ranks, Poles about the

`rebellion' against the Central Powers by Jo

Â

zef Piøsudski's Polish legion.

74

The

influence of the Czechoslovak National Council was evident again both in new

versions of S

Ï

tefa

Â

nik's original leaflet and in more optimistic proclamations

signed by the Czech e

Â

migre

Â

leadership.

75

Its role, in supplying a more political-

nationalist dimension to Czech propaganda, was undoubtedly facilitated on

the Isonzo front through the employment of Frantis

Ï

ek Hlava

Â

c

Ï

ek by military

Intelligence. By the summer of 1917 at least, he was pressing the Italians to

The Seeds of Italy's Campaign 131

scatter new Czech proclamations over the Isonzo, since his interrogation of

prisoners had convinced him that it would produce many desertions. While the

`less politically conscious' Czechs would be satisfied with assurances about

food, he emphasized that it was vital to supply the `politically more educated

elements' with `more extensive instruction', not sparing on the length of the

manifestos since these men were keen to read about the `world situation'.

Â

c

Hlava

Ï

ek was among those arguing for a more sophisticated form of front

propaganda, tuned more precisely to the mentality of various enemy soldiers,

and disseminated more carefully (for example, by night) so that it reached the

hands of its target audience.

76

It is clear that this idea of making Italy's propaganda more politicized was

gaining ground for it was evident in the content of some manifestos. A few

announced that the Entente had promised freedom to the Czechoslovaks, or

even that a new, major Entente war aim was freedom for all the peoples of

Austria-Hungary and Germany.

77

By allowing these statements to pass (and

significantly, none except S

Ï

tefa

Â

nik's leaflet spoke of Yugoslav unification), the

Italian Intelligence officers showed that they were already unconcerned if their

front propaganda exaggerated the realities of the situation. They were more

concerned about the positive effect of the propaganda. For by mid-1917, many

in the wider Italian Intelligence network sensed that `nationality politics' could

be Italy's salvation: witness the opinions of Brancaccio or of Colonel Garruccio,

head of military Intelligence in Rome, who by this time was vainly urging the

government to establish a Czechoslovak legion and was also instrumental in

preparing Borgese's Yugoslav mission to Switzerland.

78

At the front, and parti-

cularly in

the lst army, the Intelligence officers were even more sensitive to

these issues, and their practice in propaganda was almost always ahead of

Italian official policy. Marchetti's view was that the nationalist virus, stimu-

lated by

propaganda, required a period of long incubation before it could

penetrate the Austro-Hungarian armed forces.

79

But events in the summer of

1917 seemed to prove to lst army Intelligence that the virus was already fast

achieving the desired effect, infecting large numbers of enemy `cells' and

finding willing hosts among certain nationalities.

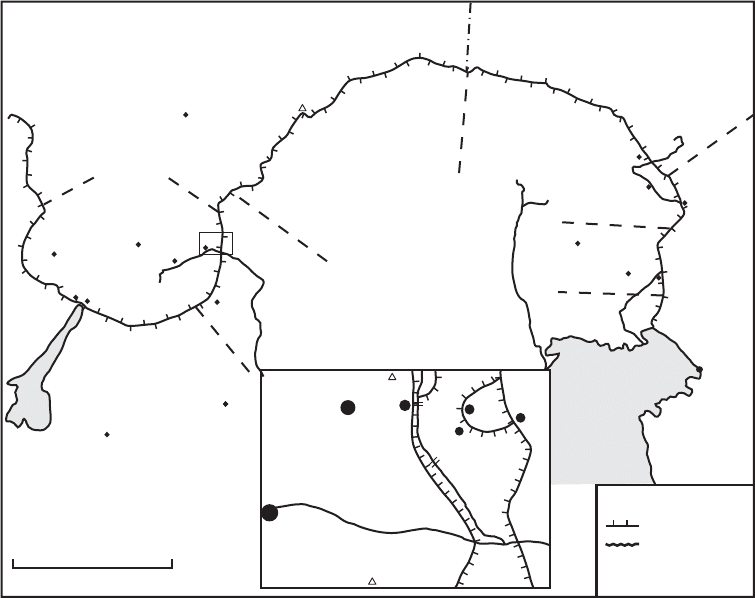

5.3 The dream of Carzano

80

On 10 July 1917, an Italian aeroplane flew over the front of the Austrian 18ID,

just north of Val Sugana, and scattered propaganda leaflets. Austrian troops in

the `Carzano sector' marvelled at the skill of the pilot: such a feat was still

highly unusual. When some of the leaflets had been brought in, they were

examined by officers of the 5th battalion of the Bosnian-Hercegovinan regi-

ment Nr

1 [V/BHIR1]. They were amused at the awkwardly composed texts, one

of which in Polish described the fate of Piøsudski's Polish legion, while another

132

BORGO

CARZANO

Castellare

SPERA

STRIGNO

R. Maso

Vicenza

1ST ARMY

11TH ARMY

4TH ARMY

6TH ARMY

2ND ARMY

10TH ARMY

5TH ARMY

3RD

ARMY

XX CORPS

ADRIATIC SEA

Bolzano

Tione

Nago

SEE INSET

Borgo

Asiago

Brenta

LAKE GARDA

Flitsch

Caporetto

Udine

BAINSIZZA

TRIESTE

Isonzo

Tagliamento

The front

10TH

4TH

0

KM

H

E

E

R

E

S

G

R

U

P

P

E

C

O

N

R

A

D

V

A

L

S

U

G

A

N

A

R. Brenta

TELVE

CAVERNA

M. CIVARON

Verona

Trento

Levico

Riva

M. SIEF

Cormons

Tolmein

Gorizia

Rivers

Austrian armies

Italian armies

Key

50

Map 5.1 The Italian Front in 1917

The Seeds of Italy's Campaign 133

simply compared the abundant Italian rations with the so-called `barbed wire'

(Austrian slang) which the Austrians themselves received as food. One of the

officers, Ljudevit Pivko, who was temporarily in charge of the battalion, resolved

that patrols should go out to recover the rest of the leaflets from no-man's-

land.

81

This was the beginning of regular Austro-Italian contacts between Pivko and

Finzi, forming the basis for the Carzano plot, one of the most notorious

attempts of the whole war to betray positions to the enemy. The daring exploit

was the brainchild of Pivko, a Slovene reserve officer, who had carefully

recruited about 70 fellow-conspirators, chiefly Czech officers and Bosnian

Serbs from the ranks. His plans, if they had succeeded on the night of 17±18

September, would have opened up the roads into northern Tyrol with possibly

devastating results for Austria-Hungary; certainly, as Pivko intended, it might

have sabotaged the Central Powers' Caporetto offensive. Instead, on the crucial

evening the Italians hesitated to act and the plotters had to flee to Italy. Yet this

did not signify total failure. Far from being a complete fiasco,

82

the episode had

major consequences for Italian warfare. It acted, in Pivko's words, `like an

invisible force which suddenly flowed up from the depths of a sandy desert

and . . . produced new vegetation far and wide'.

83

In particular, it persuaded

Italian military Intelligence even more that they should exploit nationalism

in the opposing forces. And by 1918 it provided a new basis for doing so in the

form of Czech and Yugoslav propaganda patrols, organized by Pivko in Italy.

The Carzano

plot also substantially reinforced the Austrian High Command's

fear that a nationalist poison was slowly spreading within the armed forces.

Ljudevit Pivko himself was striking proof of the degree to which an officer could

conceal his true nature from his superiors; and, as an unreliable Slovene, he

undermined even more the AOK's former categorization of their troops into

`reliable' and `unreliable' nationalities. Pivko's own anti-Habsburg convictions

had matured before the war. In civilian life, as the post-Carzano Austrian

investigation discovered, he had been headteacher at a teacher-training college

in Maribor, a town of mixed population on the sensitive German±Slovene

language border; but at the same time he was a leading personality in the

local Slovene Sokol (gymnastics) organization. Indeed, according to one police

agent, Pivko had been obsessed with the Slovene problem, a Serbophile fanatic

who in 1912 had observed that in any Austro-Serbian war the Slovenes could

not be relied on by the Monarchy. After searching his house at Maribor, police

found a book written by Pivko himself: a `History of the Slovenes', which dwelt

heavily upon the oppression of the Slavs but ended optimistically with the view

that the Slovenes would soon compete independently among the peoples of

Europe.

84

Pivko's own colourful memoirs,

85

which seem to be highly accurate when

checked against Austrian and Italian sources, suggest that from the start of the