Cornwall M. The Undermining of Austria-Hungary: The Battle for Hearts and Minds

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

84 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

propaganda guidelines and specified the organizational structure which was

inherited from the Eastern Front. But otherwise, perhaps more so than in the

East, it allowed considerable flexibility to the propaganda personnel to take

their own initiative depending on the type of terrain and the receptiveness of

the enemy on each sector of the front. Each of the four armies on the Italian

Front appointed a propaganda officer, with overall responsibility for the cam-

paign in

his sector on the following lines:

training and

planning, as well as leadership of the propaganda organs,

control of propaganda work according to the experiences on the Eastern

Front, writing of monthly reports about the state of propaganda activity,

composition of propaganda leaflets by using important, contemporary polit-

ical and

military events, replying to enemy counter-propaganda scripts and

editing of his own propaganda newspaper.

47

Subordinate to him, a general staff officer in each army corps had the task of

dictating where propaganda was necessary and where the patrols (Nachrichten-

truppen)

should be positioned. The actual propaganda activity was then carried

out by a divisional propaganda officer, somebody who had to be `completely fit

for service at the front, completely reliable, eloquent, and if possible a Tyrolian

German who at least has a grasp of Italian for official use'.

48

Such personnel

were not easy to locate. But by March 1918, after some trials and replacements,

12 of the 14 officers in the 11AK sector were of German-Austrian nationality.

A few of these had been involved in propaganda work since September 1917,

but for most of them it was a new experience. These officers were assigned one

or two interpreters who knew Italian well, and an escort of four to eight reliable

and carefully trained Nachrichtentruppen, sometimes two units per division,

whose job was to protect the officer and assist him in distributing leaflets and

confiscating enemy propaganda.

49

It was clear that because of the terrain the written word would be far more

important than on the Eastern Front. The AOK felt that besides leaflets, letters

from Italian prisoners could have a major impact if sent back soon after the

soldiers' capture. But it was a regular newspaper service which was considered

most vital, to provide the Italians with the `objective news' which they were

thought to be lacking. Special care was to be taken to make the propaganda

`true and honest' since, in Baden's view, the Italian soldier had a `higher

intelligence' than the Russian. The result of this directive was that, while

polemical manifestos appear to have been most common, the army propaganda

officers also produced a variety of newspapers containing factual information

about the war; they were designed to appear as objective and normal as pos-

sible, even

to the extent of including blank spaces to suggest that they had been

censored.

50

Austria-Hungary's Campaign against Italy 85

For the propaganda officers, however, there would always be the problem of

distribution, something which required considerable ingenuity. A common

method which quickly developed was to deposit material for collection by

enemy troops. KISA created a dozen depositing positions, some on the Piave

islands, while the 10th army by January 1918 had 30 posts which it then moved

about depending on the Italians' reaction. Even in the Alpine snow around

the Tonale pass, three propaganda officers with Nachrichtentruppen were soon

active, depositing material. One patrol described its work there on the night

of 18 January as follows:

Immediately behind

the barrier there was a sentry, smoking a cigarette. The

sound of harmonica music and cheerful shouts drifted out of the shelters.

At any moment it looked as though the sentry would be bound to see our

patrol in full view of him. In spite of this our men wearing snowcoats

moved forward, ready to shoot, and crawling to cover the last stretch.

Having deposited

their leaflets together with a letter, the head of the patrol

called out to the Italians that material had been left which would give them

true information about the war. When the Italians replied that the patrol

should come over to share in their tobacco and women, the Austrians simply

advised them to pick up the manifestos.

51

Elsewhere at the front, the Austrians

for a time alerted the enemy to their propaganda by using brightly coloured

paper which would show up in the snow,

52

or by erecting large boards which

when coated in sulphur were fluorescent at night. By this method the propa-

gandists could

also make dramatic announcements, such as `peace with Russia',

with a timeliness which astonished some British troops.

53

The real inventiveness, however, came where the front was dissected by rivers

or gorges, or where enemy hostility prevented any approach. Then mega-

phones might

be used, or the material was thrown over tied to stones or shot

over by rifle grenade, mine-thrower or even bow and arrow. In the zone of the

XX corps (10AK) a bottle post was begun both on the river Chiese and on Lake

Garda, while further north on Monte Scorluzzo small barrels filled with leaflets

were rolled down into enemy positions.

54

Under these circumstances, it was

even more natural for the Austrians to investigate distribution from the air, a

method chiefly employed in the East when no direct contact had been possible;

similarly on the Italian Front, Baden always viewed it as a substitute for per-

sonal propaganda.

In the absence of any long-range propaganda rocket, and

since hot-air balloons could be used only sparingly because of their scarcity

(propagandists were also advised to test the wind direction), there remained the

role of aircraft.

55

From the beginning the AOK had ordered their participation

in the campaign, but not without considerable opposition from the airforce

whose main fear appears to have been that Italy would execute any pilots

86 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

engaged in such work. This anxiety was not easily overcome.

56

But, as we will

see, when Baden in the late spring wished to step-up its campaign from the air,

it was thwarted even more because of the new reality of Allied air superiority on

the Italian Front. This, together with the Austrians' inability to pursue oral

contacts as fully and effectively as they had in the East, was to prove a funda-

mental weakness

in their propaganda offensive as well as a boon to the enemy's

own methods of psychological warfare.

This is

not to say that the AOK in the New Year was unrealistic about the

task which presented itself. When the euphoria of Caporetto had declined,

Baden began to view the Italian target more soberly. Apart from the obstacles

of terrain, it was soon apparent that in comparison to the Russian campaign

certain crucial ingredients were missing. In the East, domestic turmoil and

upheaval had been a vital prerequisite in dissolving military discipline and

opening up the field for propaganda to act as a catalyst. In comparison, as

Baden noted, `our propaganda against Italy lacks above all the essential base

which it would gain from a political revolution in the interior'. The latter had

not occurred, nor by January 1918 was the Italian army disintegrating. But this

still opened up a clear field of activity for Austria's front propaganda. First, it

would aim to stimulate the grievances of Italy's troops at the front. Second,

those troops would be used as the principal medium to take Austria's propa-

ganda into

the Italian hinterland (for the Swiss route, operated by the KPQ , was

always difficult to keep open); they would hopefully foment instability in Italy

which would then, as in Russia, rebound on the front and further undermine

the army. In particular, the AOK hoped that if Germany was successful in its

spring offensive on the Western Front, the Italians would overwhelmingly

demand that peace should be concluded. Advancing this idea was already the

key role of Austria's campaign.

57

Indeed, in the spring of 1918 Austria's propaganda arguments still had great

potential. Untainted by German interference, since ± as Czernin had emphas-

ized in

October ± this was to be a strictly Austrian affair, the line of argument

had been set out clearly by Baden and the Ballhausplatz in their October guide-

lines. A

major theme of these, and of supplementary guidelines issued in

February,

58

was to stress the futility of Italy continuing the war; after all, as

many Austrian leaflets showed correctly with explicit maps, Italy had achieved

virtually nothing at enormous cost.

59

After Caporetto and the reality of peace

on the Eastern Front, it was even less likely that Italy would ever secure its much

vaunted goals of Trento and Trieste. Indeed, that such pessimism existed in the

Italian interior might be deduced from the rumour that Italian parents whose

babies had been christened `Cadorna' in 1916±17, were now petitioning the

Ministry of Justice for a change of name!

60

Building on this kind of defeatist

mentality, Austrian propaganda could dwell on the high food prices experi-

enced by

ordinary Italians, and could quote Italian socialist politicians who

Austria-Hungary's Campaign against Italy 87

readily complained in parliament about widespread misery in Italy's country-

side.

61

While this information might reinforce the soldier's concern for his

family, he was also encouraged, as on the Eastern Front, to blame his political

and military leaders for this state of affairs. The Italian Foreign Minister, Sidney

Sonnino, was smeared for his imperialist ambitions against the Monarchy,

Cadorna for his ruthless regime, and a 10AK leaflet blatantly lampooned the poet-

adventurer Gabriele D'Annunzio (wearing high-heeled shoes) as a `worthy repres-

entative of

Italy's maritime power'.

62

The most striking pictorial manifesto of

this kind was one composed by the AOK and entitled `Spaghetti signori!'

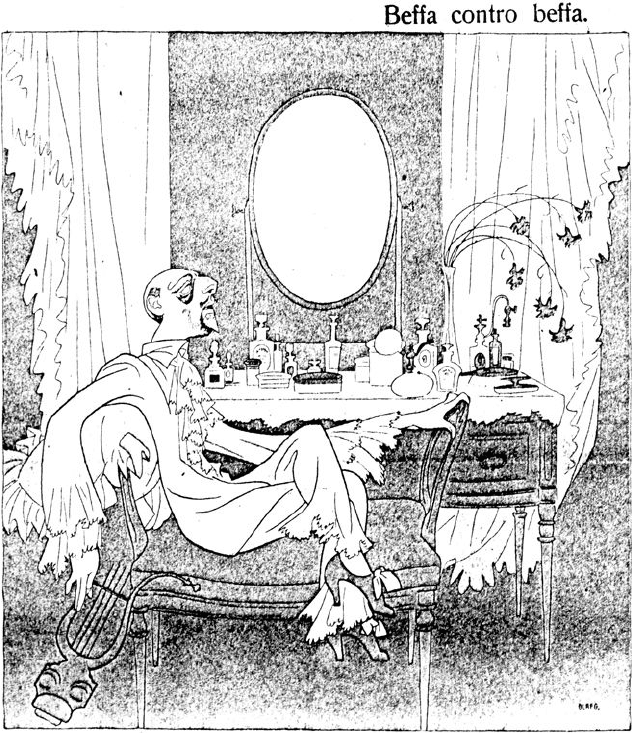

Illustration 4.1 `A Joke against a Joke': Austrian propaganda, lampooning Gabriele

D'Annunzio (KA)

88 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

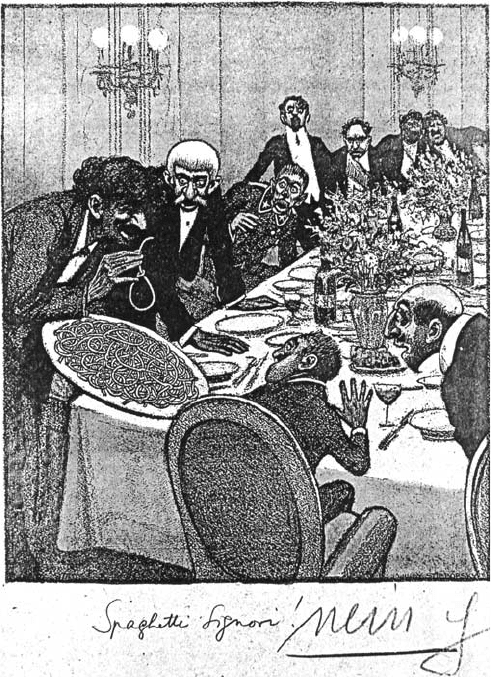

Illustration 4.2 `Spaghetti Signori!': Austrian propaganda, satirizing the Italians (KA)

It depicted someone who closely resembled the King of Italy being offered

spaghetti in the shape of a hangman's noose at a dinner party. Although there

are indications that the 11AK commander balked at such material, and the

AOK's own guidelines had advised against mocking the Italians, the leaflet was

still distributed en masse over enemy troops.

63

Austria's campaign, however, focused even more on attacking Italy's allies,

especially `England'. Here there was less danger of offending Italian feelings,

but ample scope to exploit Entente disunity. Italy was told that it was continu-

ing to

fight purely for England's rapacious and selfish dream of conquest. Just

as the English had dragged Romania into the war and then left it to fend for

itself, so they had behaved with their Italian ally, remaining largely indifferent

to Italian war aims. The AOK was quick to pick up Lloyd George's speech of

Austria-Hungary's Campaign against Italy 89

5 January 1918 to trade unionists which, in defining more precisely what Italy

could gain in territory after the war, seemed to be ample proof that `if necessary

Italy's war aims will be abandoned without consideration'.

64

And if England

was the source of Italy's raw materials (especially Welsh coal), this was simply

increasing Italy's war debts while enabling English and American capitalists

to `grow fat on the blood of the people'.

65

On the other hand, all was not well in

England itself. Adopting a technique which was to be copied and perfected

in enemy propaganda later in the year, for their newspaper propaganda the

Austrians extracted compromising items from the Entente and neutral press.

English socialists were quoted as demanding peace and Lloyd George's resigna-

tion, while

news of arbitrary arrests proved that England's old democracy no

longer existed.

66

The Daily Mail, meanwhile, provided the `most delightful'

evidence of parsimony in one of London's luxurious hotels. It published a letter

from one `glutton' who was suffering:

I found

myself a week ago in one of the most expensive and elegant hotels in

London and from the moment I arrived I was unable to obtain either a piece

of beef or a lump of sugar . . . At lunch there was served a scrap of veal, an egg,

a bit of maccaroni and a slice of pudding. For this sumptuous feast one had

to pay the best part of five shillings. Dinner consisted of some courses of

common fish, the size of a hand. Reading the menu one could fancy oneself

at a banquet, but since the hors d'oeuvre varie

Â

s were only, for example, a

sardine with a bit of cabbage salad, the merlan bonnefemme a plain fish, the

pommes de terre naturels a single potato, one remained somewhat disillu-

sioned. Evening

dress which before the war was de rigueur, has now almost

completely disappeared.

67

If the subtlety of this propaganda may have been lost on many Italian

soldiers, the Austrians soon had a far more powerful weapon to hand in dis-

cussing events

on the Western Front. As they had hoped, the military realities

there aided their campaign of ideas in Italy. Apart from the initial German

break-through in late March around St Quentin, there was the British retreat

(acknowledged even by their own newspapers), and the steady bombardment

of Paris which caused a mass exodus to the south while the French Prime

Minister, Georges Clemenceau, arrogantly behaved like a `new Nero' in the

midst of disaster

68

± all this seemed to confirm the real strength of Germany

and Austria-Hungary. While the Central Powers were easily able to transfer

forces from the Eastern Front, the Americans, in contrast, were still failing to

make any impact on behalf of the Allies. According to Austrian leaflets, by April

1918 only 200 000 Americans had arrived in Europe and most of these were

estimated by the French to be of poor quality.

69

Thus the Entente's much

vaunted promise of American help was an illusion. Not only did the Americans

90 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

prefer to send cereals rather than men to Europe, but the success of the Central

Powers' U-boat campaign (a surprisingly popular theme in Austrian propa-

ganda) sounded

the knell for Italian hopes of military or economic salvation

from across the Atlantic.

70

Against this disastrous reality in the West, Austria set before the Italians the

auspicious reality in the East. In both theatres, events in the spring aided the

propaganda campaign. The fact that the Habsburg Empire wanted an end to

the war seemed to be confirmed by its behaviour on the Eastern Front where,

with its German ally, it was concluding successive peace treaties with Ukraine,

Russia and Romania.

71

Naturally, the Italians were not to be informed about

the tortuous reality of the peace talks at Brest-Litovsk, nor about the resumption

of hostilities against the Bolsheviks in mid-February. Austrian leaflets simply

stated that peace was achieved, and they actually pre-empted the peace treaty

of 2 March with the Bolsheviks by publicizing Trotsky's premature statement

(10 February) that Russia had ceased hostilities and ordered a general demobil-

ization.

72

These favourable developments, particularly the so-called `Bread

Peace' with Ukraine which allegedly would unleash abundant grain supplies

for the Monarchy, could be set against the language of western leaders such as

Lloyd George who were rejecting peace in order to pursue their dreams of

73

conquest. This accusation was, of course, thoroughly ironic, if not duplicit-

ous. For

at Brest-Litovsk one of the major stumbling-blocks to a speedy peace

was the German military's continued obsession with annexing large tracts of

former Russian territory. The DOHL had reacted furiously when, on Christmas

Day 1917, Czernin and the German foreign minister had approved the Bol-

shevik formula

of a peace `without annexations or indemnities'. Although the

Central Powers subsequently argued that what the Bolsheviks termed `annexa-

tion' was

in fact a case of `self-determination' by former provinces of the

Russian Empire, all efforts to conclude a peace treaty on this basis came to

nothing, in part because the Bolsheviks knew the truth about German designs.

On the

Italian Front the Austrians did not have to worry about their ally and

could proceed to propagate widely a slogan of `no annexations or indemnities'.

This was calculated to undermine Italy's own annexationist designs upon the

Habsburg Monarchy. The notorious Treaty of London, which Italy had signed

with the western Allies in order to enter the war in May 1915, had promised

the Italians large tracts of Habsburg territory if they won the war. But the

slogan also fully matched Count Czernin's own wishes for any general peace

settlement; he could be quoted, in a speech of 24 January, announcing

his unswerving commitment to such a programme.

74

What this implied for

Austria-Hungary's peace settlement with Italy was spelt out in propaganda

leaflets which emphasized that the Empire had no territorial designs on Italy

and would restore Venetia to the Italians as soon as peace was concluded.

75

Yet

apart from this, and regular comments about maintaining the Monarchy's

Austria-Hungary's Campaign against Italy 91

territorial integrity, the Austrians were as cagey about precise peace terms as

they had been in the East. For example, the first propaganda guidelines, under

Czernin's influence, had expressly forbidden any discussion of the postwar fate

of Albania or Asia Minor, stressing that it was above all important to strengthen

Italy's will to peace rather than to muddy the waters with talk of peace terms.

76

It was, of course, much safer for the Austrians to make vague and simple

statements which would cast the Monarchy in a good light and also leave it

more room for manoeuvre in the future. This they could do when discussing

their future borders with Italy. For there they had a simple solution, the

status quo ante bellum, which neatly meshed with the well-known Bolshevik

slogan of `no annexations' but which they had been unable to propagate on the

Eastern Front.

If it

was natural in the propaganda for the Austrians to dwell on Italy's

weaknesses, it was equally natural that they did not dwell on their own. The

Central Powers were portrayed as confident and successful, well able to outlast

the Entente blockade because of their newly acquired, abundant resources in

the East. Most propaganda material which touched on the Monarchy's own

domestic turmoil was deemed unsuitable. A rare exception to this rule was

when the propagandists felt obliged to explain to Italy the reasons for the

widespread strikes which had hit Austria-Hungary in January 1918 largely

because of the food crisis. Austria's propaganda denied that the strikes were in

any way due to lack of food, attributing them rather to `purely political

demands of the working classes', who had soon recognized the efforts made

by `our beloved Emperor' and his government to conclude peace as soon as

possible.

77

Nevertheless, this was a sensitive issue, for simply discussing the

Monarchy's domestic affairs would usually place it on the defensive. Not sur-

prisingly, therefore,

Baden deemed some of this material too delicate for distri-

bution. This

was the fate of one rainbow-coloured manifesto, produced by the

10AK, which described an interview given by Arz von Straussenburg to a

correspondent of the Viennese Arbeiter-Zeitung on the subject of the January

strikes. Although Arz was quoted as emphasizing Vienna's keen commitment to

peace, he also mentioned the `excitement of the population' and the difficulties

of achieving peace on the Eastern Front. Perhaps for these reasons, or simply

because of his natural aversion to publicity, Arz himself appears to have vetoed

the leaflet.

78

In contrast, what could be described in full for Italy was Austria's allegedly

chivalrous treatment of Italian prisoners of war. This, of course, had long been a

natural topic for military propaganda used on all the fronts, and Austria was no

exception in recounting how prisoners worked an eight-hour day, rested on

Sundays and ate the average (supposedly ample) rations of the Austro-Hungarian

soldier.

79

What was perhaps unusual about these descriptions was the degree

to which they tried to appeal to the Italian soldier's sense of honour in order to

92 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

raise Austria's reputation in his eyes, either by informing him of heroic Italians

who had been decorated by Emperor Karl, or simply by reminding him that

Austria-Hungary did not issue appeals for desertion. Whether the Austrians

could really justify the latter claim, even at face value, is questionable.

80

And

all the more so, since their occupation of Venetia supplied them with a novel,

subversive weapon which they certainly did not shy away from employing to

undermine Italian discipline. From the start of their campaign, some of the

propaganda expressly appealed to the emotions of those Italian soldiers who

had left relatives or friends in the occupied zone. As on the Eastern Front, where

this method had proved highly useful when the allies had advanced deep into

Russian territory, the Italians were urged by leaflet to begin a traffic of corres-

pondence through

Austrian lines with their loved ones. One leaflet explained:

This method

of transmitting correspondence affords two great advantages.

Firstly, the letters reach their address quicker because they do not have to

pass the censor, and thus they travel direct from the sender to the addressee.

Secondly, you can write everything frankly. Where the Piave affords no

obstacle our patrols will show you spots entitled `Postal Receiving Centres'.

Where the Piave prevents the post being handed in direct, you can throw

your correspondence into our trenches in the manner which appears to you

most convenient. This method of correspondence shows our desire to be of

use to your families behind our lines, who are awaiting news of you with

great anxiety.

81

In fact, the letters would indeed be censored, thereby supplying useful details to

Austrian military Intelligence, while the traffic as a whole was bound to stimu-

late the

desire for peace of the Italian soldier. As an additional `depressant', the

Austrians kept him informed about conditions in Venetia through the Gazzetta

del Veneto, a newspaper which was issued by the KPQ for the Venetian civilian

population.

82

Experience would show that such material, besides lowering

Italian morale, was equally likely to incite Venetian soldiers to desert from

the Italian forces.

4.3 The impact of Austria-Hungary's front propaganda

It is clear that the arguments of Austria-Hungary's propaganda in the spring

were well matched to the mood of many Italian soldiers who had hoped in vain

for peace by the end of 1917.

83

According to one Italian journalist, who was

attached to the press office at the CS, Austria's campaign of `peace and fratern-

ization' was

indeed alarming because it seemed to be taking roots in the Italian

trenches. Its themes, Italy's failed dream of conquering Trento and Trieste or

Italy's fight for Anglo-French interests, were exactly those which suited the

Austria-Hungary's Campaign against Italy 93

rank and file's mentality.

84

This was apparent too to the Austrians from the

statements of Italian prisoners and deserters.

85

Most of them were war-weary,

some mentioning the impact which peace in the East was having, others

the continued bad treatment by their officers. Many were bitter against English

and French troops for `prolonging the war', forcing Italy to continue hostilities.

And some certainly deserted in order to reach relatives in occupied Venetia.

Those who had received Austrian propaganda said that it was read and cir-

culated eagerly,

even if they always had to be careful of their officers' vigilance.

A few also mentioned that Italy, because of the propaganda, had had to with-

draw some

unreliable Alpini troops from the front: an incident, near the river

Brenta, which is confirmed by more impartial witnesses.

86

Lastly, a few desert-

ers even

suggested that they had crossed the trenches in response to Austrian

propaganda.

87

This type of evidence was enough to convince the AOK that its campaign

was worth continuing. Aided by subversive elements in the Italian hinterland,

and boosted by news of peace in the East and a German break-through in

the West, it seemed quite likely that the combined impact could force Italy to

the peace table. Baden quickly acknowledged the positive signs in February

1918:

The propaganda

efforts in January on the south-western front have, espe-

cially in

the sectors of the 10th and 11th armies, produced very satisfactory

results. . .

. The lively exchange of leaflets and letters, and even increasing

oral discussions, indicate that the Italians are perhaps more responsive to

propaganda than the Russians.

88

True, there were some obstacles. For most of the 6AK sector no propaganda was

possible until April, when British and French troops had been transferred from

the Montello hill and replaced by Italian forces; and even then the 6AK was

hampered by bad weather and the lack of an effective printing press.

89

KISA,

however, despite the obstacle of the Piave, launched itself fully into the cam-

paign. If

in February propaganda patrols deposited or sent over 55 000 leaflets

(and even some personal contact was temporarily possible in the Piave delta),

by March this figure had doubled and was accompanied by a weekly newspaper

(Sprazzi di Luce). In April, although the high water of the Piave made it impos-

sible to

ascertain the effects, manifesto distribution was again stepped up

(150 000 leaflets) together with a regular letter-traffic.

90

But it was on the mountain front in particular that the campaign seemed to

be bearing, in Baden's words, `visible fruits'.

91

There, a certain amount of oral

propaganda was possible, something ± always most favoured by the AOK because

of the Eastern experience ± which seemed to be guaranteed proof of Italian

receptiveness. In the 10AK zone, where hostilities were scarce, the campaign