Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

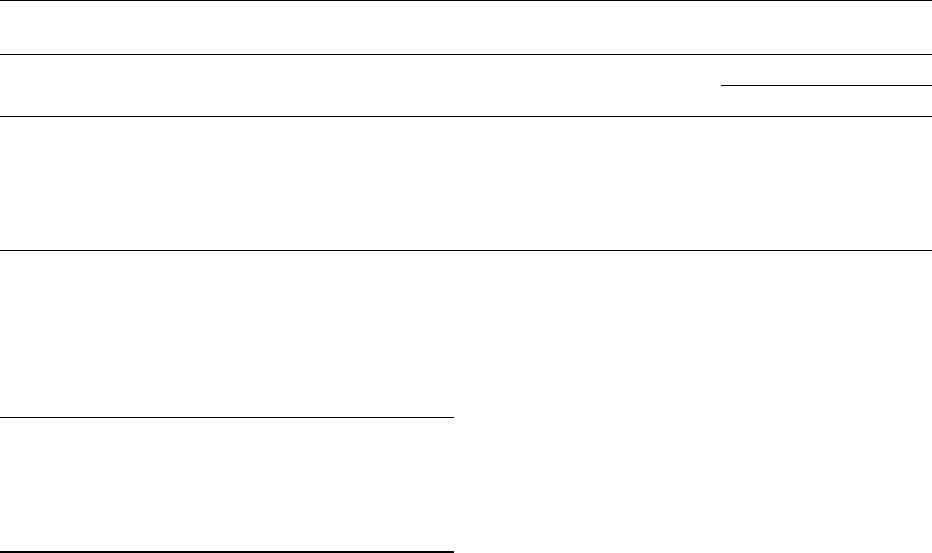

that although the DRI Panel revised calcium recom-

mendation levels upwards, the panel set adequate

intake levels (AIs) rather than RDAs ‘because redu-

cing the risk of chronic disease was the intended

endpoint [but] there were many uncertainties about

the epidemiologic and experimental data. Other

than for breast fed infants, the AI is believed to

cover needs of all individuals in the group, but lack

of data or uncertainty in the data prevent being able

to specify with confidence the percentage of individ-

uals covered by this intake.’ The AIs for calcium were

determined mainly from the intakes necessary to

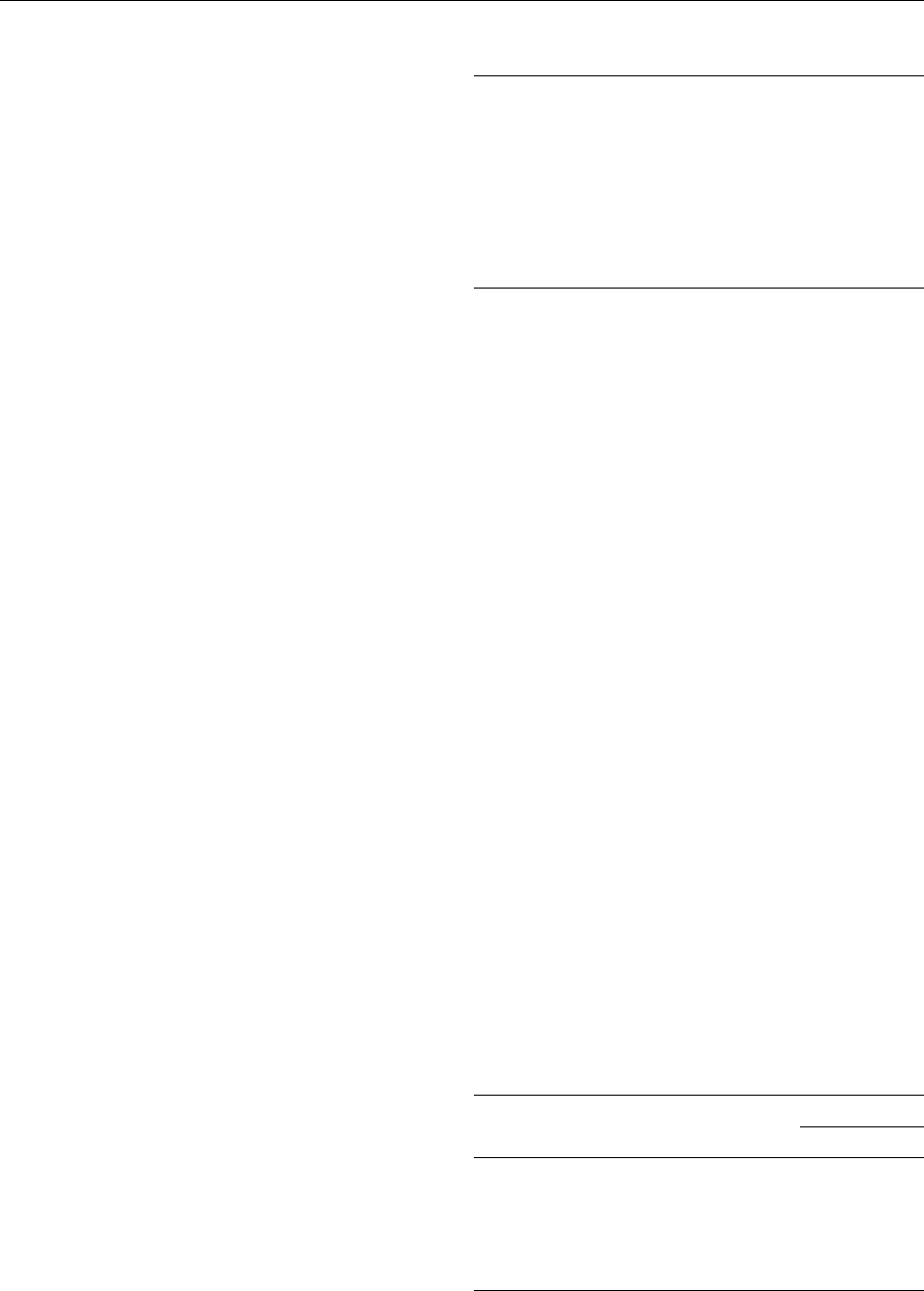

achieve maximal calcium retention. Table 2 list the

AIs for calcium by life stage group for the USA and

Canada.

Current Intakes of Calcium

Dietary Intakes

0031 No national data on the calcium intakes of Canadians

are available, although several provincial surveys have

reported relatively recent data for calcium intakes

(data were obtained from surveys conducted in the

1990s). Mean calcium intake data as well as percent-

ile distributions for Canada and the USA (from the

1994 CSFII survey) are shown in Table 3. It should be

noted that these data do not reflect consumption of

the recently introduced orange juices with added

calcium, milks with added milk solids (approx 30%

more calcium), fortified soy beverages or the

increased level of calcium in enriched flour. These

additional sources of calcium reflect recent changes

in fortification policy and industry practices in

Canada and the USA since these data were collected.

Supplement Use

0032In the Quebec survey (1990), 8–13% of men and

15–29% of women reported taking nutritional

supplements containing calcium. In the National

Health Interview Survey conducted in 1986, 25%

of women in the USA took supplements containing

calcium compared with 14% of men and 7.5% of

children.

Calcium and Osteoporosis

Definition of Osteoporosis

0033Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by low bone

mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone

tissue, leading to enhanced bone fragility and a

tbl0002 Table 2 Adequate intakes (AI) and tolerable upper intake levels (UL) for calcium by life stage group for Canada and the USA

a,b

Age AI (mg per day) (1997) Criteria onwhichAI was based UL (mg per day)

Children (male and female)

0–6 months 210 Human milk content nd

7–12 months 270 Human milk content þ solid food nd

1–3 years 500 Extrapolation of desirable calcium retention from 4

through 8 years

2500

4–8 years 800 Calcium accretion/DBMC/calcium balance 2500

9–13 years 1300 Desirable calcium retention/factorial/DBMC 2500

14–18 years 1300 Desirable calcium retention/factorial/DBMC 2500

Adult males

19–30 years 1000 Desirable calcium retention/factorial 2500

31–50 years 1000 Calcium balance 2500

51–70 years 1200 Desirable calcium retention/factorial/DBMD 2500

> 70 years 1200 Extrapolation of desirable calcium retention from 51–70-

year group/DBMD/fracture rate

2500

Adult females

c

19–30 years 1000 Desirable calcium retention/factorial 2500

31–50 years 1000 Calcium balance 2500

51–70 years 1200 Desirable calcium retention/factorial/DBMD 2500

> 70 years 1200 Extrapolation of desirable calcium retention from 51–70-

year group/DBMD/fracture rate

2500

a

As set in National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board, Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary

Reference Intakes (1977) Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium,Vitamin D and Fluoride. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

b

The AI is a recommended average daily nutrient intake level based on observed or experimentally determined approximations of estimates of nutrient

intake by a group (or groups) of apparently healthy people that are assumed to be adequate – used when an RDA cannot be determined. The UL is the

highest average daily nutrient intake level likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects to almost all individuals in the general population. As intake

increases above the UL, the potential risk of adverse effects increases.

c

For pregnancy and lactation: no additional requirements for pregnancy and lactation; requirements are the same as for the corresponding age group.

nd, not determined due to a lack of data of adverse effects in this age group and concern with regard to lack of ability to handle excess amounts. The

source of intake should be from food only to prevent high levels of intake.

776 CALCIUM/Physiology

consequent increase in fracture risk. The World

Health Organization expert committee on osteopor-

osis has defined four different diagnostic categories:

normal if BMD or bone mineral content (BMC) is

within one standard deviation (SD) of young adult

values; osteopenia (low bone mass) if the BMD or

BMC is between 1 and 2.5 SD below young adult

values; osteoporosis if the BMD or BMC is 2.5 SD

or more below young adult values; and severe osteo-

porosis if the individual is osteoporotic and has

suffered at least one fragility fracture.

Bone Structure

0034 Bone tissue is a matrix of collagen and other proteins

into which minerals are deposited, calcium and phos-

phorus being the most abundant. Calcium in bone is

primarily (> 90%) in the form of hydroxyapatite

[Ca

10

(PO

4

)

6

(OH)

2

], and amorphous calcium phos-

phate, which lacks a coherent structure, found in

areas of active bone formation. Bone is composed of

two different types of structural tissue: cortical (the

outer, denser envelope which plays a major structural

support function) and trabecular or cancellous tissue

(the metabolically more active form which is structur-

ally like a fine sponge with numerous small voids).

Cortical bone is found primarily in the appendicular

skeleton (bones of the limbs), whereas trabecular

bone is found mainly in the axial skeleton (skull and

vertebral bones). The total skeleton is composed of

approximately 80% cortical bone and 20% trabecu-

lar bone.

0035Bone contains two types of cells, osteoblasts and

osteoclasts. The osteoblasts secrete an organic matrix

composed largely of collagen, which is then hardened

by hydroxyapatite. Osteoclasts are active at numer-

ous sites within bone, secreting enzymes that dissolve

bone before it is reformed. Bone remodeling, or turn-

over, is the cycle of bone breakdown by osteoclasts

and bone rebuilding by osteoblasts and continues

throughout life. In the normal young state, total

osteoblast activity exceeds osteoclast activity, resulting

in bone accretion.

Risk Factors for Osteoporosis

0036Osteoporotic fractures are multifactorial and may

result from a variety of causes, either singly or in com-

bination. For this reason, no single risk factor can

identify all potential fracture cases. Peak bone mass is

the major factor determining the risk of developing

osteoporosis. By about age 20, the human skeleton

reaches 90–95% of its peak bone mass. Then, over

the next 10 years, the final 5–10% of bone mineral is

added. People who have achieved a greater peak bone

mass are less susceptible to osteoporosis. Numerous

factors have been identified as the major risks for

osteoporosis, including low calcium intakes and other

dietary factors, BMD, estrogen status, as well as use of

alcohol and some drugs (see Table 4).

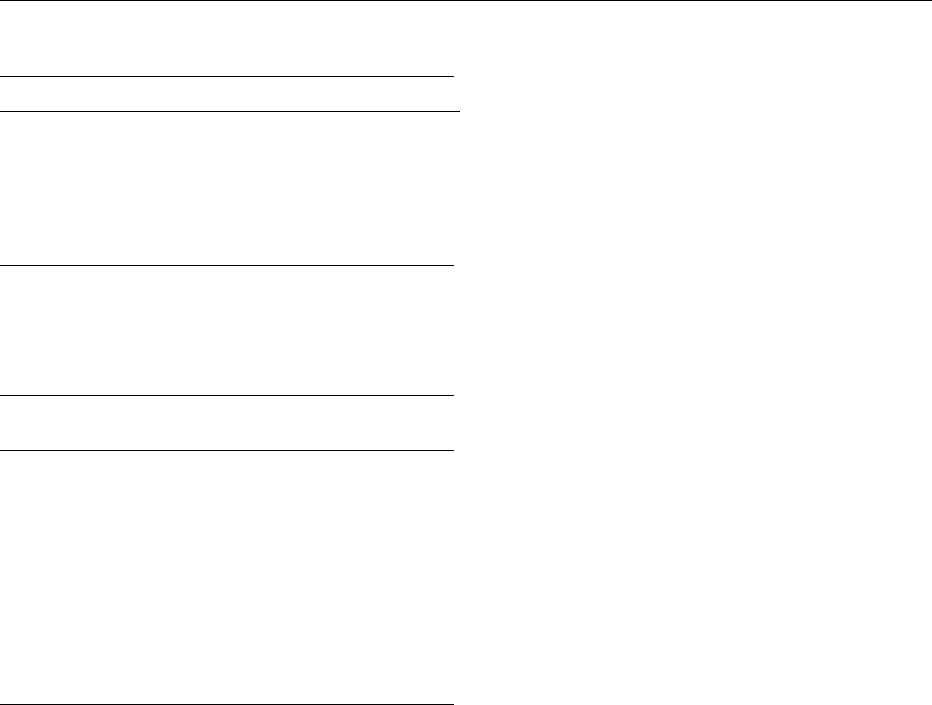

tbl0003 Table 3 Intake of calcium from foods by age and gender for the USA and Canada (mg per day)

a

Age USA Canada (data fromprovince of Quebec)

b,c

Mean 25th 50th 75th Mean 25th 50th 75th

Infants (males and females)

0–6 months 461 343 457 569 na

7–12 months 725 544 703 883 na

1–3 years 793 599 766 957 na

4–8 years 838 649 808 993 na

Males

9–13 years 1025 756 980 1245 na

14–18 years 1169 834 1094 1422 na

19–30 years 1013 729 954 1232 1114 744 984 1227

31–50 years 912 651 857 1112 922 613 769 961

51–70 years 748 545 708 908 736 575 701 845

70 years 748 548 702 880 771 476 645 904

Females

9–13 years 919 705 889 1100 na

14–18 years 753 541 713 922 na

19–30 years 647 464 612 792 788 530 688 831

31–50 years 637 461 606 779 658 407 555 770

51–70 years 599 441 571 727 622 409 539 730

70 years 536 407 517 644 574 394 524 660

a

From 1994 USDA Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals, as reported by the Institute of Medicine, Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium,

Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D and Fluoride, 1997.

b

From Sante

´

Que

´

bec, Rapport de l’enquete qu

O

˜

becoise sur la nutrition, 1995 (infants, children and adolescents not assessed).

c

Age groups do not exactly match CSFII groupings.

na, not applicable.

CALCIUM/Physiology 777

Physiologic Relationship Between Dietary Calcium

and Osteoporosis

0037 While it seems reasonable to predict that calcium

intake and bone loss would be linked, the evidence

showing this relationship has been less than obvious.

Studies comparing calcium intakes and osteoporosis

incidence or fracture rates among different countries

with varying cultures tend to show no relationship or

a negative association between calcium intakes and

osteoporosis. However, within countries or popula-

tion groups, a large body of evidence has accumulated

that shows that higher calcium intakes at various

times in the life cycle are linked with increased

BMD or BMC. Controlled clinical trials of calcium

supplementation have been conducted for almost

every age group (children and older) and, for the

most part, support the benefits of calcium for increas-

ing BMD or BMC, or in some groups reducing losses.

Fewer studies have investigated the impact of calcium

on osteoporosis or fracture rates.

0038 In children, clinical trials have shown a modest but

positive effect of calcium supplementation, particu-

larly in those children with intakes < 1000 mg per day,

on bone mineral accretion. In general, supplementa-

tion resulted in 1–5% greater gains in bone mineral

density or bone mineral content compared with

controls. However, the long-term benefits of such an

increase and whether the increase is sustained remain

unclear at the present time.

0039 Data concerning the role of calcium in bone health

of young adults are particularly lacking compared

with other age groups. Physical activity appears to

be a significant determinant of bone health in this age

group.

0040 Studies show several consistent effects regarding

the role of calcium in bone loss in postmenopausal

women. Early postmenopausal women are less

responsive to calcium supplementation than late

postmenopausal women; where effects were seen,

they tend to be in cortical bone, with spine being

less responsive to calcium. Late menopausal women

with low calcium intakes tend to gain more BMD

from calcium supplementation than do women

with higher usual intakes of calcium. Observational

studies in postmenopausal women and one study that

included men generally indicated a positive effect of

calcium on bone density. Several studies also sug-

gested that higher intakes of calcium earlier in life

were related to reduced incidence or fractures or

increased BMD in postmenopausal women.

0041Many studies conducted in the elderly have shown

a benefit of supplements or higher intakes of calcium

on the clinically important outcome – fracture rate.

Almost half of the trials in the elderly found decreased

fracture incidence, in addition to changes in BMD.

More studies in this age group than in any other have

included male subjects, and benefits appeared to

apply equally to men. In the elderly, most studies

have provided a supplement of vitamin D along

with calcium. Given that vitamin D deficiency is

most prevalent among the elderly, particularly

among institutionalized or house bound individuals,

it is important that the elderly have adequate vitamin

D in order to utilize calcium or to benefit from

additional calcium.

See also: Bioavailability of Nutrients; Bone; Calcium:

Properties and Determination; Dairy Products –

Nutritional Contribution; Dietary Requirements of

Adults; Hormones: Thyroid Hormones; Pituitary

Hormones; Milk: Dietary Importance; Minerals – Dietary

Importance; Osteoporosis; Phosphorus: Physiology

Further Reading

Brazier M, Kamel S, Maamer M et al. (1995) Markers of

bone remodeling in the elderly subject: effects of vitamin

D insufficiency and its correction. Journal of Bone

Mineral Research 10: 1753–1761.

Gibson RS (1990) Principles of Nutritional Assessment.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Lobaugh B (1996) Chapter 3: Blood calcium and phos-

phorus regulation. In: Anderson JJB and Garner SC

(eds) Calcium and Phosphorus in Health and Disease,

pp. 27–43. New York: CRC Press.

National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine, Food

and Nutrition Board, Standing Committee on the Scien-

tific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes (1977)

Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus,

Magnesium, Vitamin D and Fluoride. Washington, DC:

National Academy Press.

Packard PT and Heaney RP (1997) Medical nutrition

therapy for patients with osteoporosis. Journal of the

American Dietetic Association 97: 414–417.

tbl0004 Table 4 Major risk factors for osteoporosis

Low bone mineral density; BMD is the most useful risk factor for

stratifying people by level of fracture risk

Estrogen deficiency due to menopause (natural or surgical),

ovulatory disturbances among premenopausal women

Inadequate dietary calcium and vitamin D

Excessive intakes of caffeine

Excess dietary sodium intake

Alcohol abuse

Extended periods of immobility

Long-term use of corticosteroids

Other medications (heparin, anticonvulsants, excess thyroid

hormone, and others)

Hereditary factors

Adapted from Ross PD (1996) Osteoporosis. Frequency, consequences,

and risk factors. Archives of lnternal Medicine 156: 1399–1411.

778 CALCIUM/Physiology

Ross PD (1996) Osteoporosis. Frequency, consequences,

and risk factors. Archives of Internal Medicine 156:

1399–1411.

Wardlaw GM (1996) Putting body weight and osteoporosis

into perspective. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

63: 433S–436S.

Wood RJ (2000) Chapter 28: Calcium and phosphorus. In:

Stipanuk M (ed.) Biochemical and Physiological Aspects

of Human Nutrition, pp. 643–670. Philadelphia, PA:

W.B. Saunders.

World Health Organization (1994) Assessment of fracture

risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal

osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World

Health Organization Technical Report Series 843:

1–129.

Calorific Values See Energy: Measurement of Food Energy; Intake and Energy Requirements;

Measurement of Energy Expenditure; Energy Expenditure and Energy Balance

CAMPYLOBACTER

Contents

Properties and Occurrence

Detection

Campylobacteriosis

Properties and Occurrence

M B Skirrow, Gloucestershire Royal Hospital,

Gloucester, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 Campylobacters are the leading cause of infective

diarrhea in most industrialized countries. Yet, they

have hitherto enjoyed a low public profile that belies

their importance as a cause of foodborne disease.

There are several reasons for this. First, their role as

enteric pathogens was not discovered until the late

1970s; second, infection is rarely fatal; and third, they

seldom cause spectacular outbreaks that catch the

attention of the media. Yet, they cause much morbid-

ity and constitute a huge economic burden to society.

0002 After a brief description of campylobacters and

their properties, this article describes their wide dis-

tribution in wild and domestic animals, notably birds,

and shows how they are introduced into the food

chain from these sources. It attempts to define the

foods of greatest importance as a cause of human

infection, and the circumstances that allow infection

to arise. Although there must be many sources and

modes of transmission that remain hidden, there can

be no doubt that poultry are the most important

single source. It has been estimated that poultry

account for about half of all recorded cases.

Classification

0003Campylobacters are small, spirally curved, flagel-

lated, microaerophilic Gram-negative bacteria that

were formerly classified in the genus Vibrio. Together

with Arcobacter, Helicobacter, and Wolinella, they

form a phylogenetic group distantly related to other

eubacteria. Several species are associated with human

disease, but only Campylobacter jejuni ssp. jejuni and

C. coli are of major importance as a cause of cam-

pylobacter enteritis. C. upsaliensis and C. jejuni ssp.

doylei are associated with diarrheal disease in chil-

dren in developing countries, but to only a minor

extent in industrialized countries. C. lari is present

in abundance in birds (notably gulls) and natural

water, but most strains appear to be nonpathogenic,

as they seldom cause human disease.

0004C. fetus, the type species of the genus, is an uncom-

mon cause of systemic (bloodstream) infection in

people with impaired immunity. Although C. fetus

infection has been caused by eating raw lambs’ liver,

its low virulence for healthy people makes it of minor

concern to the food microbiologist.

CAMPYLOBACTER

/Properties and Occurrence 779

0005 Arcobacters were initially regarded as aerotolerant

Campylobacter species (unlike campylobacters, they

grow freely in air), but in 1991, the new genus Arco-

bacter was created to accommodate them. Although

they cause abortion in pigs and cattle and are com-

monly found in poultry (24–96% of fresh carcasses)

and meat (80% of ground pork samples in one study),

arcobacters (usually A. butzleri) have only occasion-

ally caused intestinal infection in humans. Until more

is known about their role in human disease, arco-

bacters remain a research topic. Our main concern

is with C. jejuni and C. coli.

0006 Helicobacter pylori, which colonizes the stomach

of roughly half of the world population and causes

gastric and peptic ulceration, can probably be trans-

mitted via food and water. Evidence is currently

indirect and inconclusive, but progress needs to be

monitored.

Growth Factors and Properties

0007 Campylobacters are strictly microaerophilic bacteria

that require oxygen for growth yet are poisoned by

concentrations much above 10%. Unlike most other

campylobacters, C. jejuni, C. coli, and C. lari have an

optimum growth temperature of 42–43

C, a feature

that has earned them the informal title of ‘thermo-

philic campylobacters.’ They do not grow below a

temperature of 28

C.

0008 Campylobacters are more sensitive to physical and

chemical agents than enterobacteria such as Escher-

ichia coli. Dense saline suspensions (10

10

cfu ml

1

)

dried on hard surfaces survive for 2–10 h at 37

C, but

suspensions in broth or skimmed milk dried and held

at 4

C survive for several weeks. Campylobacters

have a pH growth range of 6.0–8.0, but they are

inactivated below pH 5.5 or above pH 9.0. Hypo-

chlorites, phenols, iodophors, and quaternary ammo-

nium compounds kill campylobacters within 1 min at

standard working dilutions.

0009 These factors combine to prevent their multiplica-

tion in food. Unlike salmonellas and other entero-

bacteria, they tend to die in food stored at ambient

temperatures, owing to exposure to air and over-

growth by other bacteria. Their survival is prolonged

by refrigeration.

Occurrence in the Environment

0010 C. jejuni and C. coli live mainly as commensals in the

intestinal tract of a wide variety of warm-blooded

animals, notably birds (Table 1). Carriage rates in

wild mammals are generally lower than in birds, but

a rate of 24% has been found in urban rats (Rattus

norvegicus). Domestic and food-producing animals

are commonly colonized and constitute the main

source of human infection. Poultry are a particularly

important source (see below). C. jejuni is generally

the predominant species, but in pigs, virtually all the

thermophilic campylobacters are C. coli. Horses are

seldom colonized.

0011The fecal shedding of campylobacters by domestic

and wild animals results in widespread environmental

contamination, notably surface water, even in remote

areas. Campylobacters survive well at temperatures

below 15

C in fresh water, sea water, and sewage. In

these conditions, they can adapt to aerobic metabol-

ism, which is presumably a defense strategy. Surface

water is probably the chief vehicle of infection for

farm animals, and drinking untreated water carries

a high risk of infection for human beings.

Occurrence in Foods

0012Although carriage rates in food-producing animals

vary widely, both seasonally and between herds or

flocks, average figures compiled from numerous

surveys give an idea of the high prevalence of these

bacteria in poultry and animals produced for red

meat.

0013Table 2 shows the occurrence of campylobacters in

eviscerated poultry, in poultry processing plants and

tbl0001Table 1 Occurrence of campylobacters (C. jejuni and C. c oli )in

wild birds from five continents

a

Ducks and geese (Anatidae) 37 (7)

Gulls (Larus spp.) 34 (8)

Pigeons (mainly Columba livia) 25 (6)

Sparrows (Passer spp.) 18 (5)

Starling (Sturnus spp.) 47 (2)

Crows (Corvidae) 55 (4)

Also isolated from cormorant (Phalacrocorax olivaceus), caracara

(Milvago chimango), sandhill crane (Grus canadensis), waders

(Haematopodidae, Charadriidae, Scolopacidae), puffin (Fratula

arctica), owls (Strigidae).

a

The data are given as the mean percent positive, with the number of

surveys from which the data were extracted in parentheses.

tbl0002Table 2 Occurrence of campylobacters (C. jejuni and C. c oli)in

poultry

a

Birds at processingplant

Retailedproduct

Fresh Frozen

Broiler chickens 66 (22) 62 (32) 47 (9)

Chicken livers 76 (3) 48 (3) 9 (2)

Turkeys 48 (7) 22 (3) 36 (2)

Ducks 58 (5)

Geese 38 (1)

Game birds 14 (2)

a

The data are given as the mean percent positive with the number of

studies from which the data were extracted in parentheses.

780

CAMPYLOBACTER

/Properties and Occurrence

at the point of retail sale. The initial high contamin-

ation rates persist in the retailed product, with only a

modest fall brought about by freezing and thawing.

This high persistence is not surprising, considering

that cecal contents of chickens may contain as many

as 10

8

campylobacters per gram. Cuts of chicken with

skin are significantly more contaminated than those

without skin.

001 4 Table 3 shows the occurrence of campylobacters in

cattle, sheep, and pigs together with the meat prod-

ucts derived from them. Butchered carcasses in the

abattoir reflect the high intestinal colonization rates

in the live animals, but in contrast to poultry, there is

a sharp reduction of campylobacters between the

abattoir and the retailed product. This is largely due

to the forced air chilling process used on these large

carcasses (see below). Thus, contamination rates on

red meat are generally low, as are the campylobacter

counts on the positive samples. Note that offal, which

is not subjected to the same treatment, remains more

contaminated.

001 5 Table 4 shows the occurrence of campylobacters in

milk and other foods. Raw milk is clearly a major

potential source of infection, and there are many

instances of campylobacter enteritis resulting from

its consumption. Pasteurization or other conventional

heat treatment renders it safe from this threat.

Food Poisoning from Campylobacters

0016The proportion of campylobacter infections attribut-

able to the consumption of food is not precisely

known, but it is believed to be the great majority.

A few infections are acquired through direct con-

tact with infected animals or their products. These

are mostly occupational, for example, in workers

in poultry-processing plants, but some arise

through contact with domestic pets, notably puppies

and kittens that are themselves suffering from

campylobacter diarrhea. Animal contact is more

important in developing countries, where trans-

mission rates are far higher than in industrialized

countries, and the disease is virtually confined to

young children.

0017Most campylobacter infections are sporadic.

Unlike salmonella infection, outbreaks of campylo-

bacter enteritis are uncommon. In the UK, for every

campylobacter outbreak reported, there are 34 sal-

monella outbreaks. Large campylobacter outbreaks

are mostly milkborne (see below) or waterborne.

Five waterborne outbreaks, affecting a total of nearly

7000 people, have arisen from the distribution of

contaminated supplies, including unchlorinated

water from oligotrophic lakes in Scandinavia.

Incidence

0018As diagnosis depends on the identification of cam-

pylobacters in patients’ feces, measurement of

incidence depends on laboratory reports. This in

turn is dependent on the availability and use of

medical and laboratory services, which are highly

variable. Laboratory reports give incidences of

100/100 000 per year in the UK, 25/100 000 in the

USA, and 318/100 000 in New Zealand. However,

extrapolations from community surveys and out-

breaks give figures of 1100/100 000 and 1000/

100 000 for the UK and USA, respectively. The

costs in terms of health care and lost productivity

are immense. World Health statistics for foodborne

tbl0003 Table 3 Occurrence of campylobacters (C. jejuni and C. coli) in red meats and their source animals

a

Product Source animal Carcassbefore chilling

Retailedproduct

Fresh Frozen

Cattle/beef 25 (14) 12 (3) 2.9 (11) 0 (1)

Sheep/lamb 30 (9) 11 (4) 5.8 (5) 2.0 (1)

Pigs/pork 82 (14) 27 (7) 3.4 (9) 0 (1)

Offal

b

22 (8) 1.8 (3)

Miscellaneous red meats 1.3 (1)

Cooked meats 2.3 (1)

a

The data are given as the mean percent positive with the number of studies from which the data were extracted in parentheses.

b

Mostly liver, kidney, and heart from cattle, sheep, and pigs.

tbl0004 Table 4 Occurrence of campylobacters (C. jejuni and C. c oli )in

milk and miscellaneous foods

a

Raw cows’ milk (mainly bulked) 4.8 (9)

Seafood

b

9.7 (6)

Mushrooms 1.5 (1)

Salads (unsealed) 0 (1)

Salads (MAP

c

) 22 (1)

Fresh vegetables

d

2.3 (1)

a

The data are given as the mean percent positive with the number of

studies from which the data were extracted in parentheses.

b

Includes oysters, mussels, scallops, cockles, and shrimps.

c

Modified-atmosphere-packaged.

d

From farmers’ markets; samples from supermarkets were negative.

CAMPYLOBACTER

/Properties and Occurrence 781

campylobacter enteritis in the USA cite estimates of

US$ 1.2–6.6 billion annually.

Foods Implicated in Campylobacter Enteritis

0019 Having identified the foods that are regularly con-

taminated with campylobacters (Tables 2–4), we

need to define which of them are actually implicated

as sources of infection. This is not easy. As already

mentioned, outbreaks of campylobacter enteritis,

which provide good opportunities to pinpoint

sources, are uncommon. There are several ap-

proaches to the problem:

1.

0020 Comparison of the campylobacter strains com-

monly found in foods with strains found in pa-

tients. For example, strain identification tells us

that pigs are a relatively minor source of campylo-

bacter enteritis, as almost all strains in pigs are

C. coli, yet in most regions, C. coli accounts for

only about 5% of human infection. The common

serotypes of C. jejuni found in man are well repre-

sented in poultry, cattle, and sheep. In the UK,

about 70% of the strains most commonly isolated

from patients are also found in chickens. (See

Essential Oils: Isolation and Production; Pork.)

2.

0021 Identification of foods that have been implicated

in outbreaks of campylobacter enteritis. These

foods are listed in Table 5, from which it can be

seen that poultry feature prominently. The loca-

tions of these outbreaks are shown in Table 6.

3.

0022 Identification of foods that are statistically associ-

ated with infection in case-control studies. Such

studies provide two valuable indices: the relative

risk of consuming or handling a food (usually

expressed as the odds ratio); and the etiological

fraction, i.e., the proportion of infections attribut-

able to that food. Table 7 shows the foods or

activities that have been associated with a risk

of acquiring campylobacter infection. Again the

consumption of chickens, especially if they are

undercooked, stands out as a prominent risk

factor.

4.

0023Observation of the effects of eliminating or reduc-

ing campylobacters from a food on the incidence

of infection in the community that consumes the

food. In a UK study, the control of C. jejuni ser-

otype HS4:HL1 in a heavily colonized chicken

farm was followed by a fall in the proportion of

human infections with this serotype from over

30% to 5% in the community supplied with the

chickens. Likewise, in Tasmania, the escalation of

a salmonella control program in chickens, which

incidentally would have controlled campylo-

bacters, was followed by a 50% reduction in

human campylobacter infections.

The role that these various foods play in causing

campylobacter infection will now be considered in

more detail.

0024Poultry Poultry feature prominently in all of the

above categories, especially if undercooked. It is

notable that any meat cooked by barbecue, char-

grill, stir-fry, or fondue methods feature in these

lists. These hot rapid methods of cooking are liable

to leave the deeper parts of meat uncooked, even

when the outside is well browned. Handling and

preparing chicken were found to carry a much higher

risk of infection than eating chicken, in a case-control

study in the USA.

0025Broiler chickens are consumed in vast numbers, so

even though the relative risk (odds ratio) of eating

chicken is only around 3 (Table 7), the total number

of cases resulting from their handling and consump-

tion is large. Extrapolating case-control data to

estimate the proportion of sporadic infections attrib-

utable to poultry must be viewed with caution, but

two studies, one in the USA and the other in the UK,

came up with similar figures, namely 48 and 50%,

respectively.

tbl0005 Table 5 Foods other than milk implicated or suspected as the source in 83 outbreaks of campylobacter enteritis (average attack rate

41%)

a

Miscellaneous

Poultry Redmeat Seafood Salads foods Specific meal

Chicken 8 Raw beef 2 Raw clams 1 12

b

7

c

36

Undercooked chicken 7

d

Vinegared pork 1 Prawn, salmon vol-au-vent 1

Chicken liver 2

e

Red meat products 3

Turkey 2

f

a

The figures shown are the numbers of outbreaks reported in publications from 11 countries.

b

Evidence of cross-contamination from raw chicken in 7.

c

Includes pa

ˆ

te

´

vol-au-vent (1), tuna/egg vol-au-vent (1), mayonnaise (1), frozen egg (1), undercooked egg (1), cake icing (1).

d

Barbecued (2), char-grilled (1), stir-fried (1).

e

Fondued (1), pa

ˆ

te

´

(1).

f

Processed and sliced (1), boned, stuffed, and rolled (1).

782

CAMPYLOBACTER

/Properties and Occurrence

0026 Milk and Dairy Products Raw milk commonly con-

tains campylobacters (Table 4). The distribution of

inadequately pasteurized milk was responsible for the

largest outbreak of campylobacter enteritis on record.

In 1979, in England, an estimated 3500 people,

mostly primary-school children, were affected over a

period of 3 weeks. Since then, at least 58 milkborne

outbreaks have been reported in the UK and 26 in the

USA, affecting over 8000 people. The average attack

rate in exposed persons in 14 outbreaks in which data

were available was 54% (range 24–79%).

0027 In the USA, milkborne outbreaks accounted for

50% of all reported foodborne campylobacter out-

breaks. Roughly one-half the milkborne outbreaks

arose in the general community, 20% in schools or

other institutions, 17% on school visits to farms, and

8% in holiday or rural camps. In all but two in-

stances, the implicated milk was drunk raw; in the

two exceptions, the milk was distributed as pasteur-

ized, but there had been unsuspected processing fail-

ures. It is notable that four of 10 people who drank

their raw milk in coffee became infected.

0028Most milkborne infections are associated with

cows’ milk, but raw goats’ milk has occasionally

been implicated. In a survey in the UK, only one out

of 2493 (0.04%) goat’s milk samples in the UK was

found to contain C. jejuni.

0029Cheese Most cheeses are too acidic for the survival

of campylobacters, but a soft cheese made from

unpasteurized sheep’s milk was incriminated in an

outbreak of campylobacter enteritis in Czechoslo-

vakia, and there is a single instance of infection asso-

ciated with home-made ricotta cheese prepared from

unpasteurized goats’ milk.

0030In several case-control studies, the consumption of

dairy products was associated with a reduced rate of

infection.

0031Eggs The various egg-containing foods listed as sus-

pect sources of infection in Table 5 may have been

cross-contaminated from other foods. However, shell

eggs may become externally contaminated with cam-

pylobacters from chicken excreta and may thus con-

taminate egg contents when broken. Campylobacters

do not penetrate intact shell or membranes into the

egg contents. Vertical transmission to eggs from

laying hens has not been proven, but there is indirect

evidence to support it.

0032Seafood Raw seafood may harbor campylobacters

(Table 4) as well as other pathogens. In temperate

zones, contamination may be highly seasonal – high

in winter and low in summer. A study in Australia

showed that Sydney Rock Oysters (Crassostrea com-

mercialis) allowed to feed in waters containing about

10

4

cfu campylobacters per milliliter concentrated

them to 10

2

–10

3

cfu g

1

in their tissues within 1 h,

but they were effectively cleared by depuration for

48 h. Yet, depuration does not always eliminate cam-

pylobacters. A high proportion of mussels have been

found to harbor campylobacters, but conventional

steaming completely inactivates them. Seafood kept

in sea water may be contaminated from the water

rather than containing campylobacters itself.

0033Campylobacters survive for several months in

frozen oysters and for 8–14 days in refrigerated

oysters. (See Shellfish: Contamination and Spoilage

of Molluscs and Crustaceans.)

Introduction of Campylobacters into Food

Contamination of Meat at Slaughter

0034The contamination of animal carcasses with intestinal

contents at slaughter and the persistence of the

bacteria in raw meat are the most important sources

tbl0006 Table 6 Places where 67 outbreaks of foodborne

campylobacter enteritis arose (excluding milkborne outbreaks)

Place Number of outbreaks

Restaurant, hotel 34

Institution (e.g., colleges, military barracks) 13

a

School (residential and nonresidential) 8

Private home or function 4

Home for aged 3

Outdoor camps 3

General community 2

a

Includes one hospital.

tbl0007 Table 7 Foods identified as carrying a risk for acquiring

sporadic campylobacter enteritis, as determined by case-control

studies

Food Number of

studies

Odds ratio,

mean (range)

Chicken (any) 8 2.6 (0.44

a

–5.2)

Chicken (raw/undercooked) 5 6.0 (2.7–9.0)

Chicken eaten in restaurants 1 3.8

Poultry liver 1 5.7

Game hens 1 3.3

Barbecued sausages 1 7.6

Raw/rare fish 1 4.0

Raw/rare shellfish 1 1.5

Mushrooms 1 1.5

Raw (unpasteurized) milk 5 5.8 (3.9–9.3)

Raw (unpasteurized) cream 1 12.0

Milk from bird-pecked bottles 1 42.1

a

This odds ratio of 0.44 ostensibly shows a protective effect from eating

chicken. A possible explanation for this exceptional result is that many of

these chicken eaters habitually consumed chicken and had thereby

developed immunity to infection.

CAMPYLOBACTER

/Properties and Occurrence 783

of campylobacters in food. Because these are in-

extricably bound with processing methods, they

are considered below in the section on the effects of

food processing on campylobacters. (See Meat:

Slaughter.)

Contamination of Milk from Milk-producing Animals

0035 At any one time, an average of about 25% of milking

cows excrete campylobacters in their feces. Carriage

in individual animals is variable, and several strains

may circulate in a herd over a period. Some degree of

fecal contamination is unavoidable, even in well-run

milking parlors, and several outbreaks have been

caused by drinking top-grade certified milk in the

USA. Table 4 shows that, on average, 4.8% of bulked

milk contains campylobacters. Positive samples

usually have high counts of E. coli, but occasionally,

campylobacters have been found without E. coli,

probably through excretion from the udder. High

counts of C. jejuni have been found in milk from

cows with campylobacter mastitis, an uncommon

naturally occurring infection. In experimental mas-

titis, many campylobacters may be excreted from an

infected quarter before the milk appears obviously

granular.

Contamination of Milk by Wild Birds

0036 In the UK, where it is common practice for fresh milk

to be delivered to the doorstep in metal-foil-topped

bottles, magpies (Pica pica) and jackdaws (Corvus

monedula) have developed the habit of pecking

through the foil tops and contaminating the contents.

This is a seasonal activity when the birds are raising

fledglings (April to June), which is also a time when

they frequently probe cow dung for invertebrates.

The habit is geographically variable; in areas of

highest prevalence, case-control studies have shown

it to account for a high proportion of campylobacter

infections at that time of year.

Cross-contamination in the Kitchen

0037 Items of food, such as raw poultry that are heavily

contaminated with campylobacters, provide a reser-

voir of bacteria in the kitchen from which other foods

can become contaminated. This may come about

through direct contact (e.g., from the liquor of a

thawing chicken), or via common utensils, counter

tops, chopping boards, and the hands of kitchen

staff. Campylobacters have been isolated from all of

these sites in working kitchens and from 76% of the

hands of staff who had held contaminated chicken.

0038 A frequent finding in campylobacter outbreak

investigations is a failure to separate raw meats

from other foods in food preparation areas – and

often a disturbing ignorance on the part of the staff

of the need for this separation. Although it is seldom

possible to prove cross-contamination, it is probably

the most frequent event leading to infection.

0039Insects Theoretically insects could be passive

vectors of infection via food. Campylobacters have

been isolated from houseflies (2.4% of flies caught in

houses and gardens in the UK; 5.5% in Pakistan) and

cockroaches, but substantial carriage has been found

only in the close vicinity of chicken sheds and pigger-

ies. Campylobacters failed to survive for more than 2

days in flies artificially fed with campylobacter broth

cultures. (See Insect Pests: Problems Caused by

Insects and Mites.)

Fate of Campylobacters During Food

Processing

Animal Slaughter and Meat Processing

0040Contamination of animal carcasses with intestinal

contents during slaughter and preparation is univer-

sal and, to some degree, unavoidable. Fortunately, in

the case of large animals (cattle, sheep, pigs), conven-

tional forced air evaporative chilling with frequent

mechanical spraying greatly reduces the numbers of

live campylobacters remaining on the surfaces of car-

casses, mainly through the effect of drying. Cooling

without mechanical assistance causes only about a

50% reduction in campylobacter numbers.

0041Broiler chickens and other poultry pose a greater

problem owing to the high degree of mechanization

required for processing birds at rates that satisfy

public demand. Two stages of processing are particu-

larly problematic:

1.

0042Mechanical defeathering, which is preceded by

immersion in hot water (‘scalding’) to facilitate

plucking. ‘Hard scalding’ at temperatures above

58

C causes a reduction in bacterial counts, but

‘soft scalding’ at 50–52

C, used for birds that are

to be sold fresh, has little effect; thus, leakage of

intestinal contents, which is common, results in

gross cross-contamination.

2.

0043Mechanical evisceration, which often results in the

rupture of the gut of birds that are not of consistent

size. Again, widespread cross-contamination is

the inevitable consequence; birds that are initially

clean become contaminated during processing.

Contamination can be reduced, but not eliminated,

by chilling in well-designed reverse-flow systems

containing chlorinated water (10 p.p.m. chlorine).

Uneviscerated (‘New York dressed’) birds are

the most heavily contaminated; campylobacter

784

CAMPYLOBACTER

/Properties and Occurrence

counts of up to 2.4 710

7

per chicken have been

recorded. Frozen birds are least contaminated,

owing to the damaging effect on the bacteria of

freezing and thawing.

Effects of Storage

0044 The most critical factors in the survival of campylo-

bacters are temperature and oxygen concentration:

cold and reduction of oxygen tension are protective.

Campylobacter counts have been shown to decline on

stored meat by 1–2 log

10

at 4

C and 2–5 log

10

at

23

C over 2 weeks, but much depends on the particu-

lar campylobacter strain and the type of meat –

minced beef, for example, is unusually protective,

probably on account of its reducing properties.

Reduced conditions, such as are present in vacuum

or modified-atmosphere-packaged (MAP) foods, are

certainly protective. In one study, campylobacters

were detected in 22% of MAP salads from supermar-

kets (Table 4), although counts were mostly below

80 cfu g

1

. Freezing and thawing cause a 1–2 log

10

reduction in campylobacter counts, but once frozen,

survival is measured in months or even years. (See

Storage Stability: Mechanisms of Degradation.)

Salting

0045 C. jejuni and C. coli do not grow in the presence of

salt at concentrations greater than 1.5%. They can

survive for 3–5 days at room temperature in 4.5%

NaCl and for 3 weeks at 4

C in 6.5% NaCl, albeit

with a several log

10

fall in viable counts. However,

the addition of 2.5% NaCl to aerobically packaged

turkey hams reduced C. jejuni counts from about

6.0 log

10

cfu g

1

to below detectable limits within 6

days at 4

C. Campylobacters can survive on washed

pig intestines after overnight salting.

Acidification

0046 Campylobacters cannot grow at pH values of 5.5 or

less and are inactivated at pH 5.0 or below.

Irradiation

0047 Campylobacters are considerably more sensitive than

E. coli to gamma (D

10

values 0.12–0.25 kGy) and

ultraviolet irradiation, so they are destroyed by con-

ventional irradiation regimens. A gamma irradiation

dose of 1.5 kGy is sufficient to cause a 7 log

10

reduc-

tion in C. jejuni.(See Irradiation of Foods: Basic

Principles.)

Survival in Milk, Dairy Products, Spices, and Fruit

0048 Milk Most campylobacter strains are recoverable

from raw milk held at 4

C for 7 days if the initial

concentration is heavy, e.g., 10

7

cells ml

1

. Inactivation

of strains parallels a rise in the aerobic plate count and

fall in pH. Thus, survival in raw milk is about half that

in sterilized milk. The lactoperoxidase system also

reduces survival in milk. Survival becomes progres-

sively shorter as the temperature is increased, so that

at 20

C, it is only 1–2 days. Campylobacters are read-

ily destroyed by conventional pasteurization and give

D-values of 1 min or less at 60

C in raw, pasteurized,

or skimmed cows’ milk.

0049Cheese and Yogurt In one study, campylobacters

were not recovered from cheddar cheese curd after 30

days of curing, or from whey or curd of cottage cheese

after cooking for 30 min at 55

C. In another study,

no strain survived for more than 25 min in yogurt.

(See Yo gurt: The Product and its Manufacture.)

0050Egg Campylobacters can grow in egg yolk and

yolk–albumen melanges, but albumen alone is toxic.

The major factor in the sensitivity of egg white is

apparently conalbumen.

0051Spices and Fruit The spices oregano, sage, and

ground cloves are mildly inhibitory to C. jejuni,but

not sufficiently to reduce numbers in refrigerated food.

A study showed that C. jejuni survived for 6 h on cubes

of water melon and papaya at 25–29

C(8–62% sur-

vivors), but much less readily when lemon juice was

added to the surface of the cubes (0–14% survivors).

See also: Campylobacter: Detection;

Campylobacteriosis; Contamination of Food; Eggs:

Microbiology; Fish: Spoilage of Seafood; Food

Poisoning: Classification; Insect Pests: Problems

Caused by Insects and Mites; Irradiation of Foods: Basic

Principles; Meat: Slaughter; Milk: Processing of Liquid

Milk; Analysis; Salmonella: Salmonellosis; Storage

Stability: Mechanisms of Degradation; Yogurt:The

Product and its Manufacture

Further Reading

Advisory Committee on the Microbiological Safety of

Food (1993) Interim Report on Campylobacter.

London: HMSO.

Altekruse SF, Stern NJ, Fields PI and Swerdlow DL (1999)

Campylobacter jejuni – an emerging foodborne patho-

gen. Emerging Infectious Diseases 5: 28–35.

Busby JC and Roberts T (1997) Economic costs and trade

impacts of microbial foodborne illness. World Health

Statistics Quarterly 50: 57–66.

Friedman CR, Neimann J, Wegener HC and Tauxe RV

(2000) Epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni infections

in the United States and other industrialized nations. In:

Nachamkin I and Blaser MJ (eds) Campylobacter, 2nd

edn. pp. 121–138. Washington, DC: American Society

for Microbiology.

CAMPYLOBACTER

/Properties and Occurrence 785