Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Meeting Nutrient Needs

0007 Enteral formulas, which are nutritionally complete

liquid diets administered through a tube placed in

the gastrointestinal tract, are employed in most in-

stances, as the burn patient cannot usually voluntarily

ingest sufficient food to maintain an adequate energy

intake. Burn patients have been successfully treated

with the end of the tube placed either in the stomach

or in the upper part of the small intestine. It is difficult

to provide adequate energy with a low-fat enteral

diet, because the volumes required are so great. Nu-

trition by a parenteral or intravenous route may be

indicated in special circumstances, for example if the

gastrointestinal tract cannot be used. Occasionally,

parenteral nutrition may be used in combination

with enteral, when use of the latter is not providing

adequate nutrition. Parenteral nutrition, however, is

not the standard more of nutrition for the burn

patient, as it is more costly than, and has not been

shown to be superior to, other routes.

0008 Oral intake is the first choice, but it should be used

only when the patient can consume sufficient food

at meals and in between meal snacks to achieve an

adequate energy intake. Nutrient-dense snacks and

liquid supplements help to achieve an adequate

intake. Occasionally, ad libitum oral intake is com-

bined with enteral formula administered overnight to

provide adequate nutrition.

0009 Since early introduction of nutrition improves pa-

tient response to treatment, nutrient intake is initiated

within the first 24–72 h after injury, as soon as fluid

and hemodynamic status are stabilized. Early feeding

is also important, as it has been shown to help main-

tain the integrity and motility of the gastrointestinal

tract.

Nutritionally Relevant Complications

0010Complications that affect nutrition therapy of the

burn patient can be divided into three classes: (1)

those related to the thermal injury; (2) preexisting

metabolic conditions; and (3) those related to the

method of feeding, e.g., enteral or parenteral nutri-

tion (Table 2). Electric shock can have substantial

neuromuscular effects; the ability to ingest food

orally or gastrointestinal motility may be hampered

(Table 2). Inhalation injury usually means that the

patient will be placed on a ventilator. A very high

carbohydrate intake, such as would occur if a low-

fat diet were used, can exacerbate ventilator depend-

ency, and the overall macronutrient distribution of

energy needs to be evaluated in this context. Oral

and esophageal damage also can occur with pro-

longed exposure to smoke and toxic fumes and

would counterindicate oral ingestion of food. A stress

ulcer in the stomach, known as Curling’s ulcer, which

frequently occurs in the burn patient, is now pre-

vented by prophylatic antiacid therapy. The potential

for a gastric ulcer and the poor gastric emptying that

tbl0001 Table 1 Equations for prediction of energy needs of burn patients (kcal/24 h)

a

For adults:

Curreri (Curreri PW, Richmond P, Marvin J, and Baxter CR (1974) Journal of the American Dietetic Association 65: 415)

(25 kcal preburn weight, kg) þ (40 kcal %BSA)

Long (Long C (1979) Journal of Trauma 19: 904–906)

Male: 66.5 þ (13.7 weight, kg) þ (5 height, cm) (6.8 age, years) activity factor injury factor

Female: 665 þ (9.6 weight, kg) þ (1.8 height, cm) (4.7 age, years) activity factor injury factor

where the activity factor is 1.2 confined to bed and 1.3 out of bed, and the thermal injury factor is 2.1

Toronto (Allard JP, Pichard C, and Hoskino E (1990) Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 14: 115–118)

4343 þ (10.5 %BSA) þ (0.23 previous day’s kilocalorie intake) þ (0.84 basal energy expenditure) þ (114 previous day’s

average body temperature) (4.5 days postburn)

where basal energy expenditure is determined using the Long equations without the activity and injury factors

Ireton-Jones (Ireton-Jones C, Turner WW, Liepa GU, and Baxter CR (1992) Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation 13: 330–333)

629 (11 age, years) þ (25 weight, kg) (609 obesity)

where the presence of obesity is 1, and the absence is 0.

For children:

Mayes (Mayes T, Gottschlich MM, Khoury J, and Warden GD (1996) Journal of the American Dietetic Association 96: 24–29)

0–3 years: 108 þ (68 weight, kg) þ (3.9 %BSA)

5–10 years: 818 þ (37.4 weight, kg) þ (9.3 %BSA)

a

%BSA is the percentage of body surface area burned. Multiply the result of a formula by 4.18 to convert to kilojoules.

tbl0002Table 2 Pathophysiological complications of the burn patient

Related to thermal injury

Electrical burn

Inhalation damage

Gastrointestinal damage

Infection

Preexisting conditions

Cardiovascular disease

Hypertension

Obesity

Diabetes mellitus

BURNS PATIENTS – NUTRITIONAL MANAGEMENT 715

also may occur in the patient with thermal injury are

reasons why enteral (vs. oral) nutrition is used; the

stomach may be bypassed, and the feeding tube is

placed in the upper part of the small intestine.

0011 The skin is the primary barrier for the body against

the external environment. When it is lost, as in the

severely burned patient, body tissues become exposed

to the environment, which contains a variety of bac-

teria and viruses. Current therapy includes a variety

of techniques and medications to prevent and treat

infection in the burn patient. None the less, a burn

patient frequently has cutaneous infections that may

pass into the blood, causing septicemia. The fever that

accompanies an infection increases energy needs, and

septicemia also produces a hypermetabolic state.

Metabolic rate is estimated to increase about 10%

for each 1

C increase in body temperature. Nutrient

requirements need to be reevaluated in the burn

patient when an infection ensues.

0012 A thermally injured patient may have one or more

preexisting diseases that affect the overall diet pattern

(Table 2). Consideration should be given to lowering

dietary fat if the patient has significant cardiovascular

disease, and sodium if chronic severe hypertension is

present. Obesity complicates the determination of

adequate energy intakes, as well as wound closure

and healing in the burn patient. During the hyper-

metabolic phase, protein becomes a primary substrate

for energy; there is little value in providing a hypo-

caloric diet during this phase, as the obese patient will

metabolize body protein if adequate amounts are not

provided. When normal metabolic pathways resume,

consideration can be given to a modest (10–25%)

reduction in estimated energy needs when the burn

patient is obese. Careful and continual coordination

of insulin availability, blood glucose concentrations,

and food intake is needed in the burn patient who also

has type 1 diabetes mellitus, the form of the disease in

which the body does not produce insulin. Similar

monitoring is also needed for the person with type 2

diabetes, in whom insulin response to food intake is

not normal, but monitoring is less frequent. Extra

care also is needed if the patient with diabetes is

given a very high (more than 55–60% of kilocalories)

carbohydrate diet.

0013 Many of the problems associated with tube feed-

ings can be avoided by the experienced clinician. If

the infusion rate is too fast and administration of the

feeding too frequent, there can be potential problems,

particularly for burn patients, for the simple reason

that they have to be given more in order to meet their

nutrient needs. Gastrointestinal stress that usually

occurs in the burn patient is manifest as a poor empty-

ing of the stomach; thus, ‘residuals,’ or the amount of

feeding remaining 2 h after its administration, need to

be determined frequently if the feeding tube is placed

in the stomach. It is also important to keep the head

of the patient elevated (at least a 30

angle) to prevent

aspiration, which is the movement of gastric contents

toward the mouth and subsequent entrance into the

trachea and ultimately the lungs.

0014Since the feeding tube may be in place for a long

period of time, smaller-diameter tubes are used,

because they are less irritating. These smaller-bore

tubes, however, cause mechanical problems, because

they become more easily clogged. Clogged tubes are

prevented by a rigorous maintenance protocol and by

not administering ground, solid medications through

the tube.

0015Gastrointestinal complications of tube feedings

include nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, constipation,

and abdominal cramping or pain, all of which also

can be caused by the injury and by medications unre-

lated to nutrient intake. Many of the gastrointestinal

problems can be prevented by maintaining constant

administration of the feeding with a pump. Nausea,

vomiting, and abdominal cramping may be a result of

retention of food in the stomach; if this does not

resolve spontaneously within a couple of days, the

tube can be repositioned so that food is delivered to

the gastrointestinal tract beyond the stomach. Diar-

rhea can be caused by gastrointestinal dysfunction,

too rapid a rate of administration, and bacterial

infection in the gut.

Metabolic Modulators

0016Several new therapies have been proposed to counter-

act the catabolism and hypermetabolism that accom-

pany a burn injury. However, many of the studies to

evaluate these new therapies have been very limited in

scope or conducted using animal models or critically

ill patients who were not burned. This is an active

area of research, but data available at this time do not

support the use of most of these therapies. Growth

hormone administration does not appear to benefit

the burn patient. Very high doses of insulin appear to

reduce protein losses, but such doses have not been

well accepted by burn centers, as they require

frequent blood glucose monitoring. Arginine and

glutamine are viewed as conditionally essential

amino acids, that is they are indispensible in situ-

ations of severe metabolic stress when body synthesis

may be inadequate. No convincing evidence exists

that they are of benefit specifically in the burn patient,

although they are included in some protocols, on the

basis that they may help and are unlikely to hamper

recovery.

0017The use of a particular group of enteral feedings,

called immune-enhancing therapies, for the burn

716 BURNS PATIENTS – NUTRITIONAL MANAGEMENT

patient is clearly controversial, with the results of

studies indicating a beneficial effect, no effect, or

possibly a detrimental effect on the burn patient.

These formulas contain various amounts of dietary

nucleotides, arginine, glutamine, carnitine, taurine,

and/or o-3 fatty acids. These formulas are three two

four times more costly than standard enteral formu-

las, and few of these ingredients have been evaluated

for their independent effects.

0018 Metabolic complications of enteral feedings include

hyperglycemia, hypertonic dehydration, hypernatre-

mia, hyperkalemia, hypokalemia, and hypophospha-

temia. Hyperglycemia can be caused by sepsis or

severe infection and the hypermetabolism that

accompanies a thermal injury. Hyperkalemia may

signal compromised cardiac output or renal function.

Generally, these metabolic complications are very

rarely caused by the enteral feeding in the burn

patient, because intake is so closely monitored.

See also: Children: Nutritional Requirements; Coronary

Heart Disease: Intervention Studies; Dietary

Requirements of Adults; Electrolytes: Analysis; Acid–

Base Balance; Energy: Measurement of Food Energy;

Intake and Energy Requirements; Measurement of

Energy Expenditure; Enteral Nutrition; Hypertension:

Hypertension and Diet; Infection, Fever, and Nutrition;

Parenteral Nutrition; Protein: Digestion and Absorption

of Protein and Nitrogen Balance

Further Reading

Berger MM and Shenkin A (1998) Trace elements in trauma

and burns. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and

Metabolic Care 1: 513–517.

Deitch EA (1995) Nutritional support of the burn patient.

Critical Care Clinics 11: 735–750.

Garrel DR, Razi M, Larivie

`

re F et al. (1995) Improved

clinical status and length of care with low-fat nutrition

support in burn patients. Journal of Parenteral and

Enteral Nutrition 19: 482–491.

Gottschlich MM and Warden GD (1990) Vitamin supple-

mentation in the patient with burns. Journal of Burn

Care and Rehabilitation 11: 275–278.

Gueugniaud P-Y, Bertin-Maghit M, Petit P and Cardin

H(2000) Current advances in the initial management

of major thermal burns. Intensive Care Medicine 26:

848–856.

Hansbrough JF (1998) Enteral nutritional support in burn

patients. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North

America 8: 645–667.

Heyland DK and Novak F (2001) Immunonutrition in the

critically ill patient: more harm than good? Journal of

Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 25: S51–S55.

Khorram-Sefat R, Behrendt W, Heiden A and Hettich R

(1999) Long-term measurements of energy expenditure

in severe burn injury. World Journal of Surgery 23:

115–122.

Mayes T (1997) Enteral nutrition for the burn patient.

Nutrition in Clinical Practice 12: S43–S45.

Raff T, Germann G and Hartman B (1997) The value

of early enteral nutrition in the prophylaxis of stress

ulceration in the severely burned patient. Burns 23:

313–318.

Rodriguez DJ (1995) Nutrition in patients with severe

burns: state of the art. Journal of Burn Care and

Rehabilitation 17: 62–70.

Scaife CL, Saffle JR and Morris SE (1999) Intestinal ob-

struction secondary to enteral feedings in burn trauma

patients. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection and

Critical Care 47: 859–863.

Schloerb PR (2001) Immune-enhancing diets: products,

components, and their rationales. Journal of Parenteral

and Enteral Nutrition 25: S3–S7.

Vandevoort M (1999) Nutritional protocol after acute

thermal injury. Acta Chirurgiae Belgium 99: 9–16.

BURNS PATIENTS – NUTRITIONAL MANAGEMENT 717

BUTTER

Contents

The Product and its Manufacture

Properties and Analysis

The Product and its

Manufacture

E Richards, Bridgend, UK

A M Fearon, The Queen’s University of Belfast, Belfast,

UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 Butter has long been recognized as a valuable food.

Its method of manufacture has changed little over the

years except in respect of the equipment used. The

traditional craft methods have given way to large-

scale sophisticated continuous production, but both

can still be found.

0002 In the process of buttermaking, cream is subjected

to severe agitation or ‘churning.’ This causes physical

damage to the milk fat globules and results in phase

inversion from the oil-in-water emulsion of cream to

the water-in-oil emulsion of butter. Butter is com-

posed of a continuous fat phase and a dispersed

phase comprising water and globular fat. (See Col-

loids and Emulsions.)

0003 Butter is permitted to contain certain other ingredi-

ents. These include salt (sodium chloride), coloring

agents such as carotenes and annatto, acidity regula-

tors, and starter cultures for the manufacture of lactic

or ripened butter.

0004 Production of premium quality butter requires

attention to the quality of the raw material, process

hygiene, and efficiency. The equipment used in

creameries today makes a product of more uniform

flavor and texture than the older craft methods and

from a better-quality raw material.

0005 Economic forces are emphasizing the need to maxi-

mize efficiency and flexibility in processing and pro-

duction methods. Butter manufacturers have had to

reexamine their product properties and investigate

technological and other means to enhance these in

the eyes of consumers. (See Butter: Properties and

Analysis.)

Types of Butter

0006 Sweet cream:

.

0007salted with a salt content normally about 2%, but

can vary from 1.5 to 3%;

.

0008unsalted.

0009Lactic:

.

0010slightly salted with a salt content of approximately

1%;

.

0011unsalted.

0012Whey:

Sometimes called ‘farmhouse butter.’ This is found in

localized areas and is manufactured from whey cream

– a by-product of cheesemaking. The salt content is

about 2%. (See Whey and Whey Powders: Production

and Uses.)

Raw Materials

0013The quality and handling of the raw material are

of paramount importance in achieving a premium-

quality end product.

Cream

0014The essential elements are:

.

0015clean milk;

.

0016efficient separation to a specific fat content;

.

0017efficient pasteurization (heat treatment) and

cooling;

.

0018good temperature control during storage;

.

0019care in the physical handling of the cream.

(See Cream: Types of Cream.)

0020Raw milk for butter manufacture must contain less

than 100 000 microorganisms per milliliter. In fact,

milk with a much lower microbiological content (less

than 20 000 organisms per milliliter) is now com-

monly obtained from UK herds. The quality schemes

in operation within the UK insure good milk quality,

and this is reflected in dairy product standards. (See

Milk: Processing of Liquid Milk.)

0021Milk is separated into cream and skimmed milk by

means of a centrifugal separator. At all stages in the

handling of the milk and in the preparation of the

cream, care is taken to avoid damage to the fat glob-

ule membrane (FGM) by excessive pumping or tur-

bulence. The FGM is composed primarily of protein

718 BUTTER/The Product and its Manufacture

and phospholipid and stabilizes the fat phase in milk

while also protecting the fat from oxidation and

enzyme attack. Separators are designed to cause as

little damage as possible, while achieving a high degree

of efficiency.

0022 The optimum fat percentage of the cream, to

obtain the maximum churning efficiency, needs to

be adjusted according to the method and equipment

used to make the butter. Traditional methods advise a

fat content of 30–35%, whereas modern continuous

buttermakers normally operate at 40–44% butterfat

for sweet cream and 38–40% butterfat for an acid or

cultured cream.

0023 Cold separation (<10

C) has the advantage that

milk may be processed on arrival at the factory. Al-

though the separation is less efficient, free fat levels

are low, and the cream has a higher phospholipid

content. This improves its whipping properties.

0024 Heat treatment of the cream can be achieved on a

small scale by heating in a vat to a temperature of not

less than 63

C and holding the cream at that tem-

perature for at least 30 min. This ‘holder method’ is

slow and inefficient, as heating and cooling are

carried out in the same vessel. It is only suitable for

small quantities of cream.

0025 For larger-scale production, cream is treated in a

continuous high-temperature, short-time (HTST)

plate heat exchanger to a minimum of 72

C for at

least 15 s. At higher processing temperatures, there is

a danger of oxidative rancidity promoted by migra-

tion of copper from the serum to the fat globules.

For this reason, it is recommended that cream used

for buttermaking be processed at a maximum of

77

C for 15 s. However, in practice, flash heating to

85

C is often used to produce a desirable slightly

nutty or caramelized flavour. (See Pasteurization:

Principles.)

0026 Feed and weed taints concentrate in the fat phase of

milk, and these may be removed by vacreation, a

form of heat treatment under vacuum. The heated

cream is held in contact with steam under reduced

pressure, then separated to allow volatile taints

to be drawn off. This is a combined heating and

flavor-stripping treatment. Evaporative cooling to ap-

proximately 60

C may also be used to adjust the fat

content of the cream. The final cooling of the cream

takes place in a plate heat exchanger. A milder, flavor-

stripping method using vacuum treatment after an

HTST process may also be used.

0027 The cream used for buttermaking must be cooled

and stored at a low temperature to encourage crystal-

lization of the fat. This period, usually a minimum of

8 h, is often called ‘ageing’ the cream. The latent heat

released will increase the temperature of the cream to

7–8

C from the initial cooled temperature of 5

C.

Aging is essential to achieve a low fat loss into the

buttermilk and produce butter of the desired texture.

(See Butter: Properties and Analysis.)

0028Both the rate of cooling and the temperature of

holding are important in determining the size of the

fat crystals and the proportion of solid-to-liquid fat

achieved within the final butter. Large silo tanks for

storage are preferable to a series of small cream tanks.

There is improved homogeneity, allowing the butter-

making equipment to operate with a more consistent

product for a longer period.

0029Cream temperature treatments (‘Alnarping’) may

be applied to improve butter spreadability and pro-

duce a consistent butter despite seasonal variation

in milk fat composition. However, these have had

limited success. A more effective means has been

through altering the cow’s diet to increase the propor-

tion of unsaturated fatty acids in milk fat. This

reduces butter firmness at low temperatures. Incorp-

orating vegetable oils into cream and applying mar-

garine process technology have been very successful

developments, but the resultant products may not

be identified as ‘butter’.(See Butter: Properties and

Analysis.)

Water

0030Water, wherever used, must be of the highest possible

microbiological quality.

Lactic Cultures

0031A soured or ripened cream is traditionally required

to produce lactic butter. Although it is possible to

allow milk or cream to sour naturally, it is neither

advisable nor practical. A culture of lactic micro-

organisms – Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris (for-

merly Streptococcus cremoris), Lactococcus lactis

ssp. lactis (formerly Streptococcus lactis), Lacto-

coccus lactis biovar. diacetylactis (formerly Strepto-

coccus diacetylactis) – may be added to the cream

to produce the desired acidity, flavor, and aroma.

The primary aroma producers are L. lactis biovar.

diacetylactis and Leuconostoc mesenteroides ssp.

cremoris.(See Lactic Acid Bacteria.)

Salt

0032Salt adds flavor and also acts as a preservative in

sweet cream butter. For short-term storage, bulk

butter is stored at temperatures of 18

C whether

it has added salt or not. Intervention (EC-subsidized)

butter – for long-term storage – is unsalted and is

stored at 25

C.

0033Only pure, finely milled, vacuum-dried salt (of at

least BSI 998 (1969) or equivalent standard) should

be used for butter.

BUTTER/The Product and its Manufacture 719

Manufacturing Processes

Churn Method

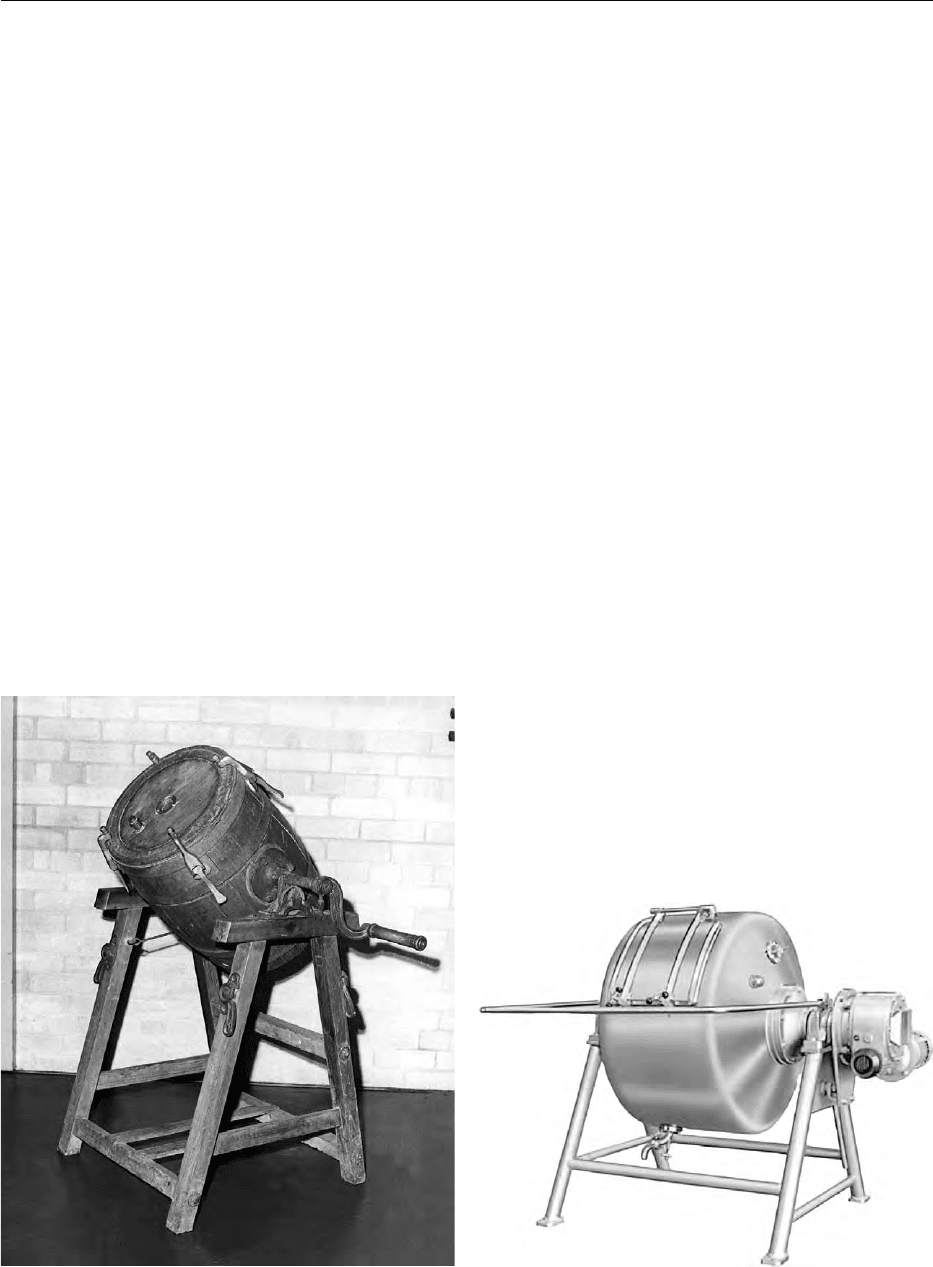

0034 Batch process A batch-type butter churn may vary

in capacity from a few liters up to maximum of about

45 000 l. These churns were originally made of wood

(Figure 1) but latterly of stainless steel (Figure 2).

0035 After cleaning and disinfection, the churn must be

specially prepared to prevent the butter from sticking

to the surface. With wood, this is achieved by scalding

with boiling water and immediately cooling with

chilled water. This treatment leaves a film of water

on the surface of the wood and prevents the butter

from adhering to it. All wooden equipment must be

kept wet until used.

0036 The surface of stainless steel equipment also re-

quires special physical preparation. The detergents

used in the cleaning of such equipment must contain

silicates to maintain the special ‘nonstick’ surface.

(See Cleaning Procedures in the Factory: Types of

Detergent; Types of Disinfectant.)

0037 Batch butter churns may be barrel- or cone-shaped

with fixed or rotating internal ‘workers.’ As the churn

is rotated, the combined actions of rotating and

beating cause the cream emulsion to break, forming

the butter grains (fat phase) and buttermilk (aqueous

phase).

0038During the first few turns, gases, e.g., carbon diox-

ide from heterofermentative fermentation, may be

liberated from the cream. In order to maintain an

even pressure within the churn, it is necessary to

release these gases. This is done by depressing a

small valve in the lid of the churn.

0039Each churn has an indicator glass – a small window

through which it is possible to see what is happening

inside the churn. When hand churning, the cream

feels heavier as it begins to thicken. This takes about

15–20 min from the beginning of churning. The cream

emulsion breaks and small grains of butter form.

These are clearly seen on the indicator glass. The

actual size of the butter grains varies according to

the type and size of the churn. It is essential not to

allow them to grow and form lumps, which will cause

an uneven distribution of buttermilk.

0040For hand churning, the grains should be kept small,

approximately 3 mm in diameter – traditionally

stated as the size of wheat grains.

0041Chilled water at approximately 5

C is added to

harden and control the size of these grains, as well

as removing the traces of buttermilk. Washing re-

duces the yield, and is not necessary if the cream is

of good quality and all the necessary hygienic precau-

tions have been observed in the preparation of the

butter churn.

0042Salt may be added dry or in the form of brine as a

final wash. The addition of brine (10% solution) to

butter grains has been used to reduce the need for

chilled water. This can be important during warm

weather when there is a lack of chilled water. It will

fig0001 Figure 1 Wooden butter churn (nineteenth century). From

National Museums and Galleries of Northern Ireland, Ulster

Folk & Transport Museum, with permission.

fig0002Figure 2 (see color plate 12) Stainless steel batch butter churn

(twentieth century). From APV Unit Systems, Denmark, with per-

mission.

720 BUTTER/The Product and its Manufacture

also prevent streakiness due to uneven mixing of the

salt. For dry salting, the calculated quantity is

sprinkled on to the butter grains to give approxi-

mately 2% in the final product.

0043 The butter grains are ‘worked’ to expel excess

moisture, create an even, fine distribution of water

droplets and produce a close textured, evenly colored

product. This may be carried out using the workers

inside the churn or externally on a small scale, by using

Scotch hands. These are made of grooved wood (or

plastic) and are also used to shape and print attractive

designs on the finished packs (Figure 3).

0044 During the period of working, drainage, and add-

ition of dry salt, samples are tested to determine the

salt and moisture contents. The operator determines

the ‘end point’ of working when the moisture content

is between 15.5 and 16% and by visual assessment of

the butter. At this stage, the butter is removed from

the churn in readiness for packing.

0045 The moisture content of butter must not exceed

the legal maximum of 16%. Manufacturers attempt

to be as near to that limit as possible to ensure the

maximum yield.

0046 Cultured butters Traditionally, cream is inoculated

with specific cultures of bacteria. The reduction in pH

and development of flavors produce a lactic-flavored

end product. This is regarded by some as a more

desirable product, i.e., a fuller-flavored butter. (See

Starter Cultures.)

0047 This method of making butter requires starter cul-

ture facilities with the necessary laboratory controls,

and additional equipment such as cream-ripening

tanks as well as cooling and aging facilities. There

must also be a well-controlled program of tempera-

ture controls and pH monitoring.

0048The cream is inoculated with approximately 1% of

culture and incubated at 20–27

C to achieve a final

pH of 5.3–4.7, depending on the preferred lactic

flavor. The cream is then cooled to stop the fermenta-

tion and to attain the desired fat crystallization.

0049The method of manufacture on a batch basis is no

different from that employed for sweet cream. The

disadvantage of this traditional system is that the

buttermilk has a lactic content that causes problems

in its disposal. The behavior of the starter culture is

not always consistent, and this can result in end-

product variations.

0050Because of the problems and expense of culturing

cream and the disposal of ‘lactic’ buttermilk, several

methods have been developed to make lactic or

cultured butter from sweet cream.

0051The NIZO method developed in the mid-1970s

consisted of churning sweet cream and adding a

special mix containing cultured whey concentrate

and bacterial culture while working the butter grains.

This gave the major advantage of being able to manu-

facture from sweet cream, thus producing sweet

cream buttermilk, which has a far greater commercial

value than cultured cream buttermilk.

0052The indirect biological culturing system, as de-

scribed, for example, by Pasilac – Danish Turnkey

Dairies Ltd, involves the addition of two types of

prepared starter culture to the churn at the working

stage. The combination of aroma-producing bacteria

and the acidity of the culture mix result in the final

pH and flavor of the butter conforming to that of

traditional cultured butter.

0053The addition of a starter distillate provides an al-

ternative method of flavoring butter without the need

for culturing equipment, while acidity is increased by

addition of lactic acid.

Continuous Buttermaking

0054Continuous buttermaking equipment began to be

widely used in the 1960s. The success of this equip-

ment was such that, within a decade, most of the

batch churns used in commercial butter manufacture

had been superseded.

0055Continuous buttermaking equipment gives an ad-

vantage over the batch process in terms of hygiene,

uniform product quality, and process efficiency.

0056Cream processing is an integral part of the

whole buttermaking system. The preparation of

the cream is similar to that for traditional manufac-

ture. From the storage tanks, it is pumped into the

first stage of the buttermaker at a constant speed and

temperature.

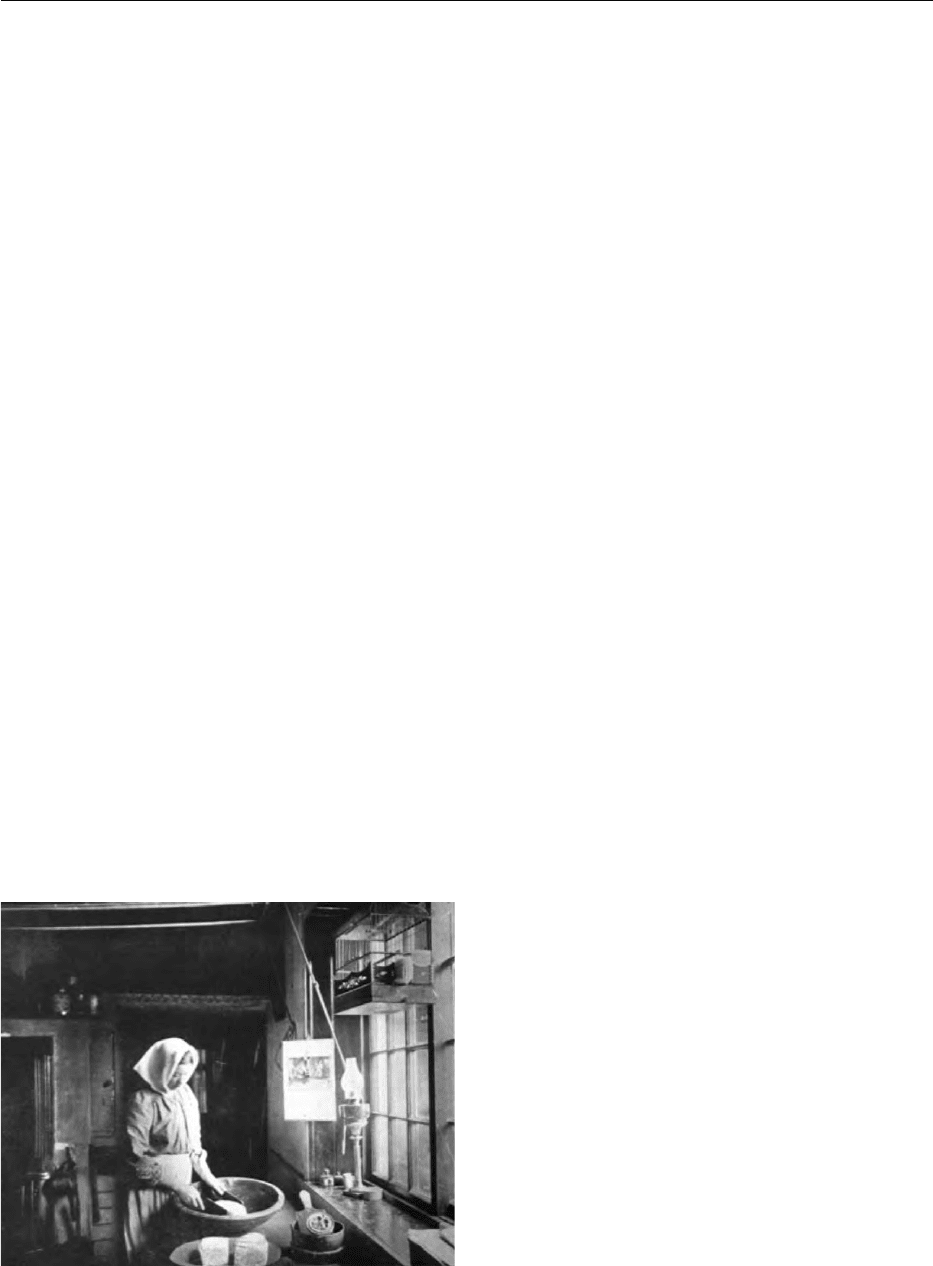

fig0003 Figure 3 Using Scotch hands to work butter. From National

Museums and Galleries of Northern Ireland, Ulster Folk & Trans-

port Museum (L882/10), with permission.

BUTTER/The Product and its Manufacture 721

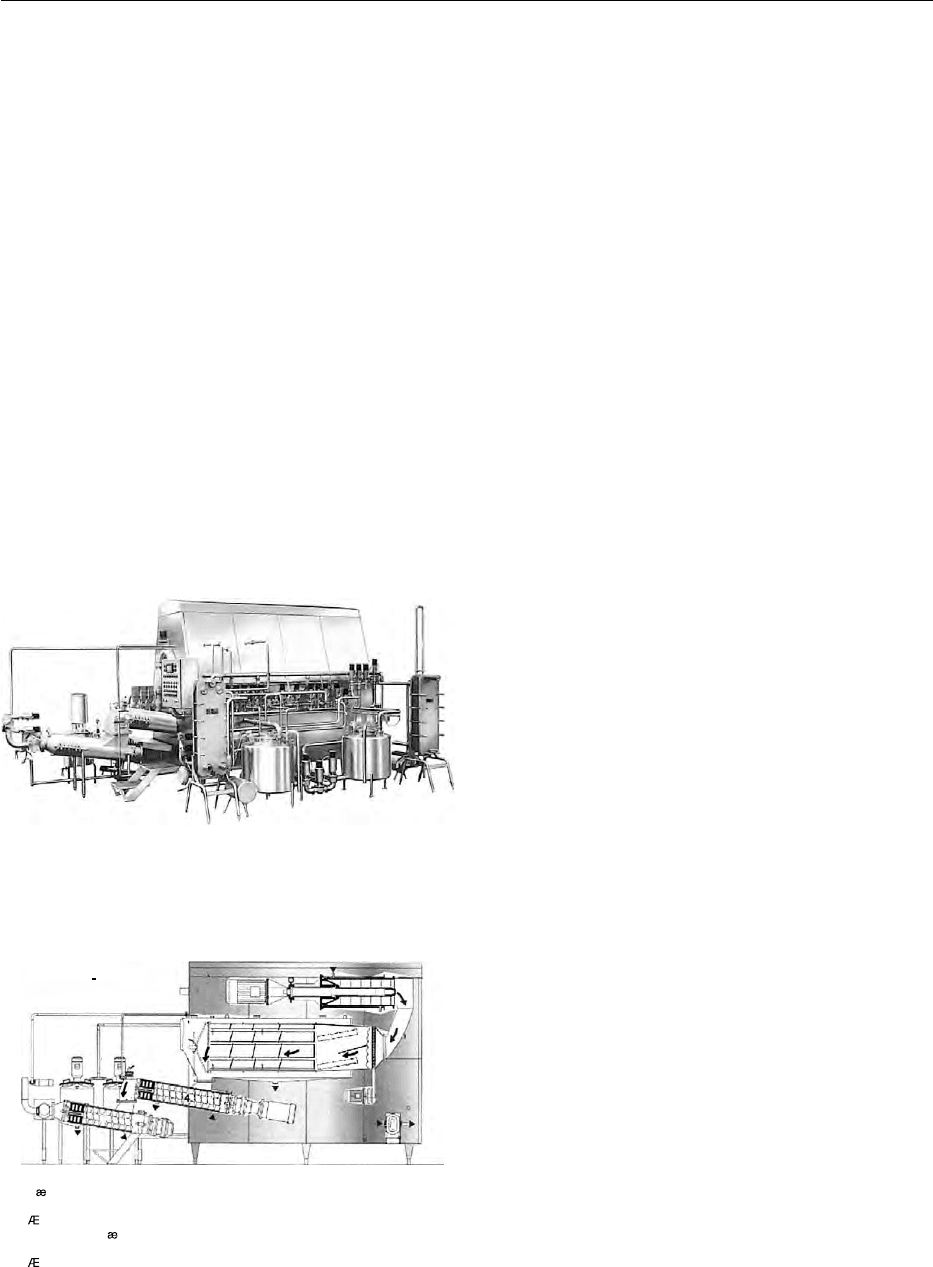

0057 The capacity of continuous buttermakers varies

from small units of 12 kg h

1

to more than

10 000 kg h

1

(Figure 4).

0058 Although design features vary, the basic principles

remain the same. A continuous buttermaker consists

of: (1) the churning section; (2) the separating section

and (3) the working section(s) (Figure 5).

0059 Churning section A multibladed beater operating at

high speeds (approximately 1000 rpm) within a cylin-

drical chamber introduces air into the cream and

damages the fat globules. The distance between the

cylinder wall and the beater blades is only 2–3mm.In

just a few seconds, the cream emulsion is broken, and

the initial agglomeration of fat globules takes place. A

mixture of small butter grains and buttermilk is then

transported from this beating chamber into the next

unit, the separating chamber.

0060 Separating chamber This consists of a rotating

drum where the final churning takes place and in

which there is a perforated filter – a separation

drum – to separate the buttermilk from the butter

granules. The drum rotates slowly so that as the

buttermilk is drained away, the butter grains are

gradually clumped together.

0061Cooling may be achieved by circulating chilled

water in the walls of either churning chamber. In

some machines, the first buttermilk is cooled and

recirculated. It is in this particular section that the

grains of butter are allowed to grow to the required

size.

0062The speed of the beaters, the temperature of

churning, and the butterfat content of the cream will

all vary slightly. An experienced butter manufacturer

will adjust these parameters according to the season,

equipment, texture, and consistency of the resultant

butter. A firmer milk fat and, therefore, firmer butter

are obtained in winter than in summer. In addition,

the temperature of the cream has to be maintained at

a lower temperature, e.g., 5–7

C, in summer, whereas

it could be at 10

C in winter.

0063There is an observation window for the operators –

similar to the sight glass of traditional equipment.

The control panels may also have display screens,

allowing operators to observe the processes inside

the machine.

0064Working sections Augers transport the butter along

the working sections and through aperture plates.

The process kneads or works the butter, expelling

more buttermilk and influencing the final body and

texture of the finished product. The moisture droplets

must be fine and evenly dispersed.

0065During this process of working, salt (if required) is

added in the form of a 50% saturated slurry. Water

may be added to adjust the final moisture content,

and in the case of lactic butters, the mix of flavor

distillates or concentrated bacterial cultures is added

at this stage. The second part of the working section

operates at a much higher speed to ensure that the

culture or salt is correctly distributed.

0066The working sections are cooled with chilled water.

The link between the first and second working

sections operates under vacuum. This provides con-

trolled deaeration of the butter, thus giving the end

product a very close texture and improving the shelf-

life. The body and texture of butter worked under

vacuum are quite different from the open structure of

traditionally worked butter.

0067To allow for the stoppages that must occur during

normal production, a ‘balance tank’ is maintained

between the buttermaker and packing equipment to

buffer flow variation (Figure 6). This butter ‘trolley,’

as it is known, is constructed of stainless steel and

performs the essential task of maintaining the flow of

Standardudforelse:

Standard design:

Standardausfuhrung:

3

2

1

5

6

4

7

8

1. Flodepumpe 1. Cream pump

2. Chuming section

3. Separating section

4. Working section I

5. Regulating gate

6. Vacuum chamber

7. Working section II

8. Butter pump

1. Rahmpumpe

2. Butterungsabteilung

3. Trennabteilung

4. Knetabteilung I

5. Reglerplatte

6. Vakuumkammer

7. Knetabteilung II

8. Butterpumpe

3. Separeringsafdeling

6. Vakuumkammer

8. Smorpumpe

2. K meafdeling

5. Reguleringsspj ld

4. teafdeing l

7. teafdeing lI

fig0005 Figure 5 Schematic outline of a continuous buttermaking

machine. From APV Unit Systems, Denmark, with permission.

fig0004 Figure 4 Continuous buttermaking machine. From APV Unit

Systems, Denmark, with permission.

722 BUTTER/The Product and its Manufacture

butter both from the buttermaker and to the packing

equipment.

Packing

0068 Wholesale The butter is packed in bulk or retail

packs directly from the churn or from the trolley of

a continuous buttermaker. Bulk butter is normally

packed in 25-kg quantities in cardboard cartons.

These can be lined with parchment paper, but colored

polythene, enabling the inner wrapper to be readily

seen, is the preferred lining material.

0069 The simplest form of bulk butter packer is the

‘Vane’-type packer – this is simply a hopper into

which the butter is fed, either manually or pumped

from the buttermaker trolley. The butter is extruded

by a screw-conveyor through a suitably sized nozzle

into the lined carton. When the carton is full, the flow

of butter is stopped, and the butter is ‘cut’ with a

heated wire. The full carton is then removed and

checked for weight, which is adjusted manually. The

liner is closed, ensuring there is no exposed product,

and the carton is sealed, coded, and palletized. The

normal quantity is 50 cases of 25-kg butter per pallet.

0070 For large-scale production, automatic packers are

normally an integral part of continuous buttermaking

installations (Figure 7). The cardboard cartons are

loaded flat, and the inner wrap is polythene from a

reel. The machine forms the carton, lines it, and

presents it for filling. Once full, the weight is checked,

and if necessary, additions are made via an ‘injection

unit,’ which adds the required quantity of butter

below the original surface.

0071On achieving the correct weight (25 kg), the liner is

folded over the top surface, and the carton is closed,

sealed, and coded. This minimal exposure to possible

contamination has contributed greatly to the exten-

sion of the keeping quality of butter. Automatic pal-

letization is also a feature of some installations.

0072Retail Butter is required to be sold in metric quan-

tities. Most retail packs are in 250- or 500-g weights.

The shape of the packs vary from a brick of differing

dimensions to rolls, and packs may be foil- or parch-

ment-wrapped. Attractively designed plastic tubs

holding 250 or 500 g are also available.

0073For retail packing, the butter is formed in an ap-

propriately shaped chamber on a rotating drum. This

formed portion (roll or brick) is pushed out of the

chamber into the waiting coded wrapper (parchment

or foil), which is then folded. The portions are check-

weighed before passing onwards to an automatic case

packer and palletizer. The butter at this stage is still

very soft in consistency, and any mishandling is likely

to deform the portion.

0074Catering butter portions are packed in foil or plas-

tic tubs with foil lids. The machines developed to

pack this size of butter portion must operate at max-

imum efficiency. The quality of the butter, in terms of

body and texture, is of secondary importance. The

butter is extruded into the partly folded foil held

within a shaped chamber, and the folding is then

completed. Alternatively, the butter is discharged

into a plastic tub before sealing.

0075Larger catering packs, e.g., 2-kg plastic tubs, are

filled by extrusion before the lid is applied.

0076Reworked butter For marketing or distribution

reasons, it may be necessary to rework bulk butter.

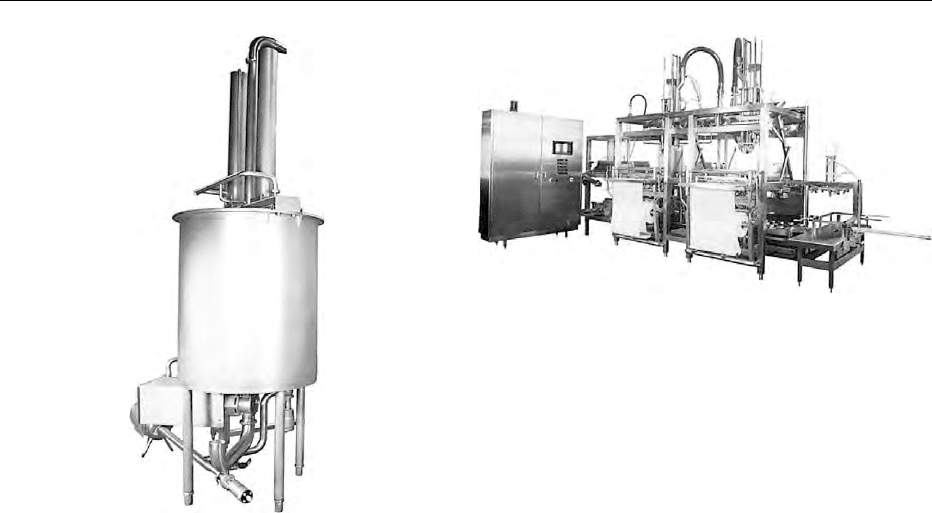

fig0006 Figure 6 Butter buffer tank. From APV Unit Systems, Denmark,

with permission.

fig0007Figure 7 Butter packing line. From APV Unit Systems,

Denmark, with permission.

BUTTER/The Product and its Manufacture 723

This butter, in 25-kg blocks that have been stored at

either 18 or 25

C, can be either attemperated,

i.e., brought to a temperature suitable for packing,

before working, or handled frozen.

0077 Attemperation traditionally involves placing bulk

butter in a store at 5–8

C for a period to attain that

temperature. The use of microwave tunnel heaters

has reduced the space and time necessary, and is a

more efficient way of attemperation. Blocks of butter

may be brought up to blending temperature within

hours, then blended and standardized on a batch or

continuous basis to the required salt and moisture

contents for packing.

0078 An alternative process employs a butter reworking

system that first chops the frozen butter blocks into

strips. The spaghetti-like strips of butter leave the

chopping unit at a temperature of 0–2

C. They

are then transferred into the blender where they are

worked several times and vacuum-treated before

repackaging in retail units (Figure 8).

Product Evaluation

007 9 Notwithstanding the aesthetic requirements of pack-

aging and any legal requirements, the most important

quality parameters of butter are its taste and keeping

quality.

0080 The modern continuous machines and their associ-

ated equipment are normally cleaned in place (CIP).

Close collaboration between the design engineers, op-

erators, and quality controllers is necessary to ensure

effective cleaning. (See Plant Design: Basic Principles;

Designing for Hygienic Operation; Process Control

and Automation.)

0081 Attention to detail, monitoring the critical aspects

of the process, whether it be batch or continuous, is

essential. It is, however, normal to sample the finished

product to confirm that the desired microbiological,

chemical, and organoleptic qualities have been

achieved.

Microbiological

0082Microbiological guidelines for the acceptance of bulk

butter into intervention storage are described by the

Intervention Board for Agricultural Produce. For

butter to be acceptable, it must have:

0083Total viable count: < 1000 organisms per gram

(maximum 5000);

0084Coliforms: absent in 1g;

0085Yeasts and molds: less than 10 g

1

.

Chemical

0086Butter composition and protection of use of the des-

ignated term ‘butter’ are described by the EC Council

Regulations No. 1898/87 and No. 2991/94, respect-

ively. Butter must contain not less than 80% milk fat

but not exceeding 90%; a maximum water content of

16% and a maximum dry nonfat milk material (milk

solids not fat) of 2% are permitted. Substances neces-

sary for the manufacture of butter may be added, but

such substances may not be used to replace in whole

or part any milk constituent. Regulations for butter

composition in other major butter-producing coun-

tries, New Zealand (Regulation 111. Butter, Food

Regulations 1984) and USA (US Code of Federal

Regulations Title 7, Volume 3, 7CFR58.345 and

Title 21, Section 321a), are similar to the EC regula-

tions. However, the New Zealand regulations also

permit the fat phase used to prepare butter to

be standardized for consistency by the removal or

addition of physically fractionated fractions, pro-

vided that the fatty acid profile of the butter falls

within the typical range. Such a product must then

be identified as ‘standardized butter’. The Australian

New Zealand Food Standards Code may be found at

www.anzfa.gov.au/foodstandardscode/.

0087Constant monitoring of the moisture and salt levels

– where appropriate – is carried out during process-

ing. On-line devices are available that link the

machine controls to the moisture and salt determin-

ations. These are necessary to match the manufactur-

ing speeds now possible where traditional chemical

analysis is too slow. However, these automated

techniques still require calibration against standard

laboratory methods.

Organoleptic Grading

0088The grading of butter involves much more than the

tasting of the product. Grading normally takes place

no less than 48 h after manufacture – a period neces-

sary to allow the butter to ‘cool’ and ‘settle.’ Scoring

standards and identification of defects are described

for butter for intervention storage in the Official

Journal of the European Community (1995) No.

fig0008 Figure 8 (see color plate 13) Butter reworking system. From

APV Unit Systems, Denmark, with permission.

724 BUTTER/The Product and its Manufacture