Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Quaglia G (1992) Scienza e tecnologia della panificazione.

Pinerolo: Chiriotti Editori.

Rehm HJ and Reed G (1983) Baked goods. In: Biotechnol-

ogy: A Comprehensive Treatise, Vol. 5: Food and Feed

Production with Microorganisms, pp. 1–83. Weinheim:

Verlag Chimie.

Ward OP (1989) Fermentation Biotechnology: Principles,

Processes, and Products Milton Keynes, UK: Open

University Press.

Zimmermann FK and Entian KD (1997) Yeast Sugar

Metabolism: Biochemistry, Genetics, Biotechnology,

and Applications. Lancaster, PA: Technomic.

BREADFRUIT

D Ragone, National Tropical Botanical Garden,

Kalaheo, HI, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 Breadfruit has long been a staple food in the Pacific

islands and is now widely distributed and used

throughout the tropics, as is a related species known

as breadnut. The discovery of breadfruit by western-

ers and subsequent distribution of breadfruit and

breadnut in the 18th to 20th centuries are discussed.

Two species of breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis and

A. mariannensis) and breadnut (A. camansi) are de-

scribed. The importance and use of breadfruit in vari-

ous Pacific island groups and methods of preparation,

including traditional techniques to preserve fruits, are

summarized. Production and use of breadfruit and

breadnut in the Caribbean includes information on

local and export markets. Harvest and yields of both

crops are discussed. Use and nutritional composition

of breadfruit and breadnut for fresh consumption are

provided, as is an overview of commercial processing

and postharvest handling of breadfruit.

History and Distribution of Breadfruit and

Breadnut

0002 Breadfruit derives its name from the fact that the

fruits, when baked or roasted, have a starchy, dense

consistency similar to bread or root crops such as

potatoes, yams, or sweet potatoes. Native to New

Guinea and possibly also the Moluccas, breadfruit

has been an important staple crop for more than

3000 years. Islanders spread it throughout the vast

Pacific during their voyages of exploration and dis-

covery. By the late 1500s, when western ships first

ventured into the region, breadfruit had been estab-

lished in every island group settled by indigenous

islanders. The only exceptions were New Zealand,

which was too cool for this subtropical plant, and

certain small coral atolls in Micronesia and Polynesia,

where it was too dry to grow the tree.

0003Breadfruit was a remarkable and delicious food for

western sailors arriving on those distant shores. Voy-

ages to the Pacific from Europe were arduous,

months-long passages, and the quality of food served

to the crew became more and more unpalatable as the

voyage progressed. The main provision was generally

weevil-infested hardtack (flour and water baked

into a biscuit). The sailors were delighted with this

new island food. Fresh-roasted in a fire, breadfruit

has a satisfying, aromatic smell, much like bread as it

comes out of the oven. Its moist, dense, doughy

texture and subtle flavor round out its similarity

to bread. The scientific name, Artocarpus altilis,is

derived from the Greek, with artos meaning bread,

carpus meaning fruit, and altilis originating from the

word utile, meaning useful, and has memorialized it

as the tree which produces fruits like bread.

0004As those voyagers returned home they spread the

word about this wondrous new plant and its potential

as a food crop for other tropical countries. The grow-

ing interest in breadfruit set the stage for one of

the grandest sailing adventures of the 18th century –

Captain William Bligh’s ill-fated mission on HMS

Bounty to introduce Tahitian breadfruit to the Carib-

bean – and the extraordinary tale of courage and

sailing skill that saved the survivors of the mutiny.

The hundreds of breadfruit plants aboard ship were

less lucky; the mutineers tossed them all overboard

and sailed back to Tahiti and then on to Pitcairn

Island.

0005Lesser known is that in 1793 Captain Bligh suc-

cessfully completed his mission by introducing more

than 600 plants of several seedless Tahitian cultivars

to the islands of St Vincent and Jamaica. Most of the

breadfruit in the Caribbean today originated from

those plants. During this period the British and

French also distributed breadfruit to Mauritius, the

Maldives, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka. In the 19th and

early 20th century breadfruit was widely distributed

throughout the tropical countries of the world:

Central and South America, India, South-east Asia,

northern Australia, Africa, and Madagascar. How-

ever, its popularity and use vary greatly by locale.

Breadnut, A. camansi, a closely related species from

BREADFRUIT 655

the Philippines – grown for its nutritious, high-

protein seeds – was also introduced to other tropical

areas where it is now widespread, especially in the

Caribbean, parts of Central and South America, and

coastal West Africa.

Description of Breadfruit and Breadnut

0006 A member of the Moraceae or fig family, breadfruit

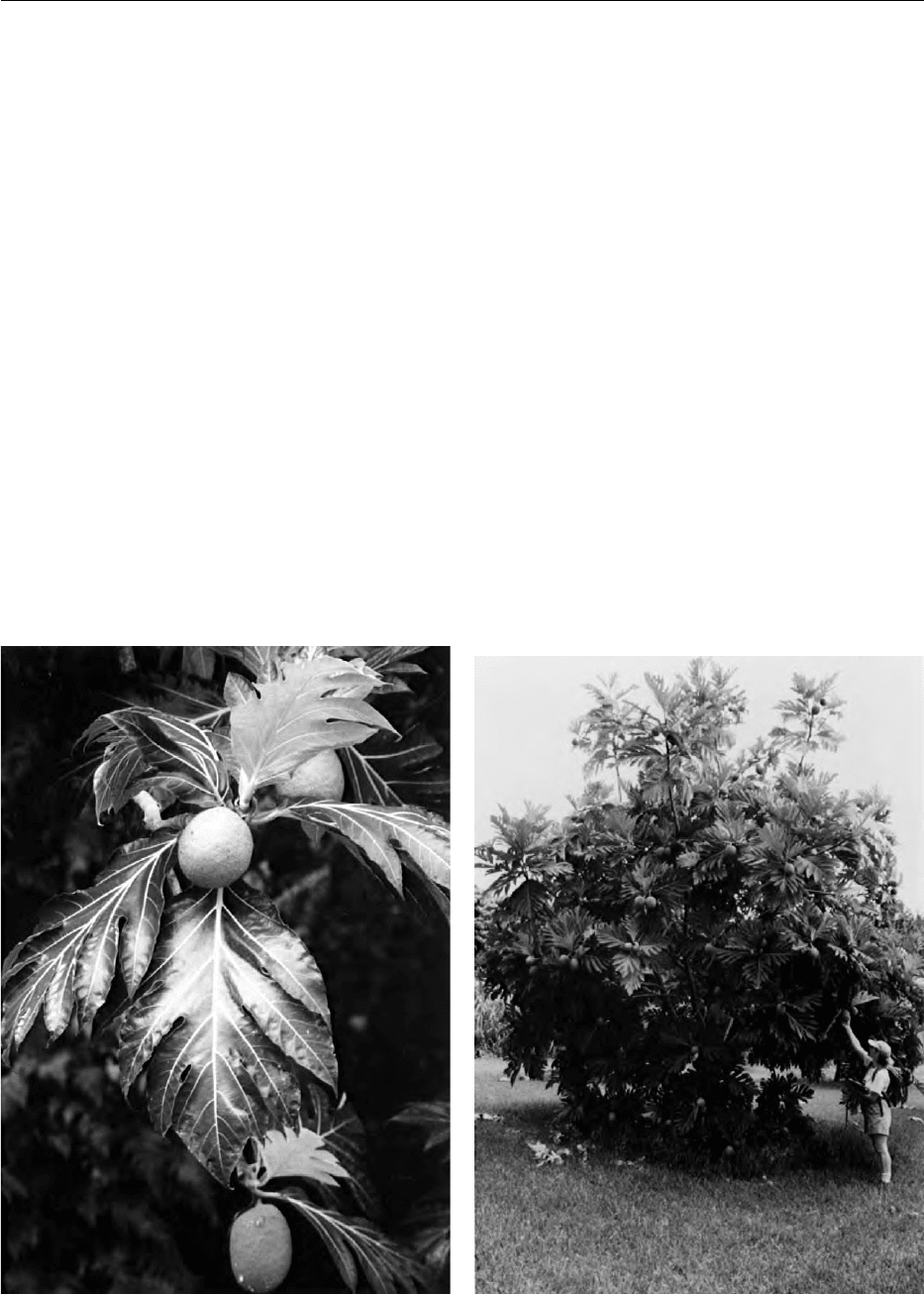

is a stately and attractive evergreen tree reaching

heights of 15–20 m or more. The tall, straight trunks

may be as large as 2 m in diameter at the base. It has

large glossy, dark-green, leathery leaves ranging from

almost entire with only slight lobing to deeply pin-

nately lobed (Figure 1). The long-lived, multipurpose

trees begin bearing in 3–5 years (Figure 2) and are

productive for many decades. They provide nutritious

food, timber, and medicine, as well as feed for

animals. The trees require little attention and input

of labor or materials and can be grown under a range

of ecological conditions.

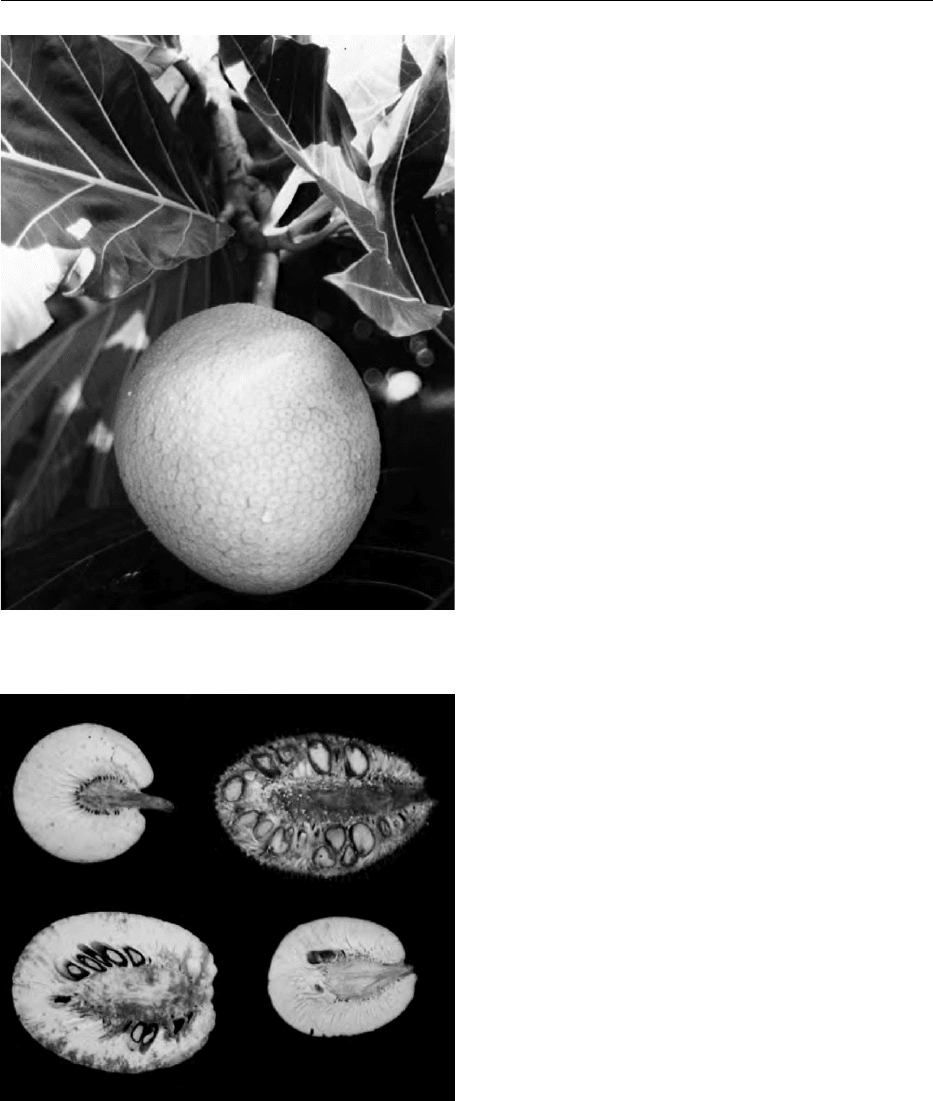

0007 Fruits are usually globose (Figure 3) to oblong,

ranging from 8 to 20 cm wide and up to 30 cm long

and weigh from less than 0.5 kg to more than 5 kg,

depending on the cultivar. Each fruit is composed of

the fused perianths of up to 2000 flowers attached to

the fruit axis or core. As the fruit develops this area

grows vigorously and becomes fleshy at maturity,

forming the edible portion of the fruit. The rind is

attractively patterned with five- to seven-sided disks,

each representing the surface of an individual flower.

In the center of each disk is a distinctive scar formed

by the withered remains of the stigmatic lobes. The

fruit rind is light green, yellowish-green, or yellow

when mature and often stained with dried latex exud-

ations. The surface varies from smooth to slightly

bumpy or spiny. The flesh is creamy white or pale

yellow in color and may be seedless except for numer-

ous minute, abortive seeds surrounding the fruit core.

Seeded breadfruit contain from one to many normal

seeds (Figure 4). Breadfruit is considered to be parthe-

nocarpic and does not require pollination to develop

normally.

0008A third species of breadfruit, A. mariannensis,

grows wild in the islands of Palau, Guam, and the

Mariana Islands and is cultivated throughout the

islands of Micronesia. The leaves are generally

smaller and glossier than those of A. altilis and

fig0001 Figure 1 Typical fruit and leaf of seedles breadfruit.

fig0002Figure 2 Productive 4-year-old breadfruit tree.

656 BREADFRUIT

A. camansi. They are usually entire or have a few

lobes, typically in the upper third of the leaf. The

dark green cylindrical or asymmetrical fruits are gen-

erally smaller than breadfruit, with deep yellow-

colored flesh when mature. Each fruit contains sev-

eral to many seeds. Hybrids between A. altilis and A.

mariannensis are common in Micronesia.

Production and Use

In the Pacific Islands

0009Breadfruit has long been an important staple crop in

the Pacific Islands, and the islanders have selected and

cultivated hundreds of cultivars. In Melanesia, seeded

breadfruit grows wild in lowland areas of New

Guinea, and the seeds are a valued food and an

important component of the subsistence economy.

Breadfruit is cultivated throughout the Solomon

Islands and is a major subsistence food only in the

easternmost islands. Breadfruit is equally important

in Vanuatu, and it is still widely grown and used in

certain areas of Fiji. Throughout Polynesia, bread-

fruit is an important staple food crop, especially in

Samoa. Breadfruit remains the main staple food on

atoll islands in Micronesia, and is the most important

crop in season on the high volcanic islands where it is

a primary component of traditional agroforestry

systems.

0010While most breadfruit is produced for subsistence

purposes, small quantities of fresh breadfruit are

available for sale in village and town markets, espe-

cially in population centers where urban households

must purchase traditional foods and rely heavily on

imported foods. In Hawaii, fresh breadfruit is occa-

sionally available in ethnic grocery stores and from

local farmers’ markets, but demand far exceeds

supply. There is interest in establishing commercial

breadfruit plantings to provide fresh fruits and chips

for the local market and export. Although little

breadfruit is currently exported from the Pacific

islands, a large potential market for fresh fruits exists

in the large communities of Pacific islanders living in

Auckland, Honolulu, Los Angeles, and other urban

areas of the USA and Canada.

0011Everywhere in the Pacific the starchy fruit is basic-

ally prepared and consumed in a similar fashion. It is

typically cooked by roasting halved or whole in an

open fire or earth oven, boiling, or occasionally is

fried as chips. Because breadfruit, like all starch

crops, is relatively bland, islanders have developed

simple methods to enhance its flavor. Freshly grated

and squeezed coconut cream is often added. A popu-

lar preparation is pudding made from mature or ripe

cooked breadfruit that is grated or pounded, mixed

with coconut cream, wrapped in leaves and baked. In

many islands, these starchy puddings are the main

form in which breadfruit is consumed. Puddings

make a portable, tasty travel food that keeps for

several days. Steamed or boiled breadfruit is also

pounded until it becomes paste-like or doughy. It is

preferred when at least 1 day old and can be kept for

several days, when it begins to ferment and sour.

fig0003 Figure 3 Smooth-textured globose breadfruit.

fig0004 Figure 4 Variation in seed number of breadfruit and breadnut.

BREADFRUIT 657

0012 Traditional methods of preserving fruits Since

breadfruit is a seasonal crop that produces much

more than can be consumed fresh, Pacific islanders

have developed many techniques to utilize large har-

vests and extend its availability. Preserved breadfruit

also adds diversity to the daily diet. Drying is the

simplest method for preserving breadfruit. Cooked

breadfruit is halved or sliced into bite-sized pieces

and dried over hot stones heated in a fire. Occasion-

ally, thin slices are dried in the sun. Dried breadfruit is

usually eaten without additional preparation, but it

can be made into soup or ground into meal and mixed

with water or coconut cream to make a porridge.

0013 The most common method of preservation is the

preparation of pit-preserved breadfruit. Pit storage

is a semianaerobic fermentation process involving

intense acidification which reduces fruit to a sour

paste. Analysis of breadfruit fermented for 7 weeks

showed that the starch was broken down first to

maltose, then glucose, and eventually to lactic acid

and carbon dioxide. Protein and carbohydrate levels

remained relatively unchanged, while fat content and

iron and calcium levels increased slightly (Table 1).

0014 Fermented breadfruit is still made every season

throughout Micronesia and to a limited extent else-

where in the Pacific. Mature fruits are peeled, cored,

and in the atolls, soaked in sea water for 12–48 h. They

are then placed in a leaf-lined pit (Figure 5) and

covered with leaves and a thick layer of soil or rocks.

Fermented breadfruit can last for a year or more, and it

is removed and eaten at various stages of fermentation

depending upon need and taste preference. Fermented

breadfruit is usually washed, then pounded or

kneaded, and cooked before being eaten. Traditional

storage practices are being modernized to fit contem-

porary lifestyles. Fermented breadfruit can be made in

plastic tubs, coolers, or other containers that can be

made relatively airtight. There are several advantages:

it yields a cleaner, more uniform product, it is less

labor-intensive, and smaller quantities can be made.

In the Caribbean Islands

0015In the Caribbean breadnut and breadfruit are both

widely grown, with seedless breadfruit more com-

monly cultivated and used. Since its introduction in

the 1790s it gradually became an accepted food and

an important component of the daily diet. In most

cases, breadfruit is used to supplement other staple

starchy foods in season and is the main source only

in certain rural areas. It is a major source of food

in Jamaica where more than 2 million trees were

estimated to be growing in the 1970s. In the Wind-

ward Islands breadfruit is very popular for backyard

planting in urban areas, and scattered trees are found

island-wide. Breadfruit is prepared boiled, steamed,

or roasted, and has lent itself to the creation of

regional dishes such as ‘oil down’–made with salt-

cured meats, breadfruit, coconut milk, and dasheen

leaves – which is popular in Trinidad, Tobago, and

Grenada. In season, fresh breadfruit can be found in

any local market, and a small quantity of processed

breadfruit products such as frozen, dehydrated, and

canned slices, flour, chips, and candied male flowers

are also locally available. Breadnut is popular mainly

in Trinidad, Tobago, and Guyana where immature

and mature seeds are boiled and eaten as a snack.

0016The Caribbean is the major supplier of breadfruit

to Europe, the USA, and Canada, providing more

than 90% of the fruits for the UK market, with the

rest coming from Mauritius. Jamaica is one of the

largest exporters in the region. Most of the fruits are

tbl0001 Table 1 Proximate composition of breadfruit and breadnut

seeds per 100 g (dry weight) edible portion

Breadnut seeds

a,c,d

Breadfruit seeds

b

Water (%) 56.0–66.2 47.7–61.9

Protein (g) 13.3–19.9 7.9–8.1

Carbohydrate (g) 76.2 26.6–38.2

Fat (g) 6.2–29.0 2.5–4.9

Calcium (mg) 66–70 46.6–48.3

Potassium (mg) 380–1620

Phosphorus (mg) 320–360 186–189

Iron (mg) 8.7 2.3

Magnesium (mg) 10.0

Niacin (mg) 8.3 1.8–2.1

Sodium (mg) 1.6

Thiamin 0.13–0.33

Riboflavin 0.08–0.10

Ascorbic acid 1.9–22.6

Data from

a

McIntoch C and Manchew P (1993) The breadfruit in nutrition

and health. Tropical Fruits Newsletter 6: 5–6;

b

Murai M, Pen P and Miller CD

(1958) Some Tropical Pacific Foods. Honolulu: University of Hawaii;

c

Negron

de Bravo E, Graham HD and Padovani M (1983) Composition of the

breadnut (seeded breadfruit). Caribbean Journal of Science 19: 27–32;

d

Quijano J and Arango GJ (1979) The breadfruit from Colombia – a detailed

chemical analysis. Economic Botany 33: 199^202.

fig0005Figure 5 Leaf-lined breadfruit fermentation pit in Micronesia.

658 BREADFRUIT

harvested from backyard trees and small plantings,

but there are efforts underway to establish orchards

to support and expand the export market in the

Caribbean.

In Other Tropical Areas

0017 Breadfruit is more a subsistence crop than a commer-

cial crop in most areas of the world, with the Pacific

and Caribbean islands being the major production

areas. In season, breadfruit and/or breadnuts supple-

ment other staple foods for home consumption in

Indonesia, the Philippines, and parts of West Africa,

Central and South America, South-east Asia, India,

and Sri Lanka. Some fruits may be available at local

markets in these areas, especially Indonesia. Bread-

fruit has never been adopted as a major foodstuff in

Africa, possibly because of failure to introduce ways

of making the fruit into a food acceptable to local

tastes. Recently, farmers in Queensland, Australia,

have become interested in establishing breadfruit

orchards for the export market.

Harvest and Yields

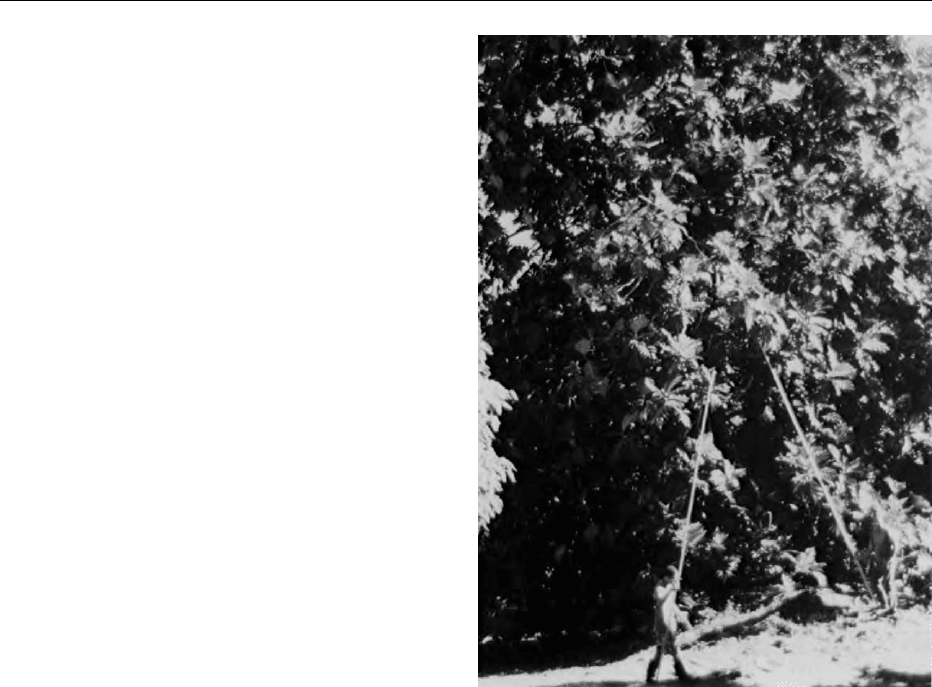

0018 Breadfruits are harvested as needed and generally

picked when mature, but not yet ripe. Breadnut

seeds are harvested from ripe fruits and the seeds are

separated from the soft pulp. Breadfruits are usually

harvested with a sharp scythe or curved knife at-

tached to the end of a long, sturdy pole (Figure 6)

and are allowed to drop to the ground in most areas.

Fruits that fall to the ground are damaged and soften

sooner than those that are hand-picked. Most yield

estimates are very general and a figure often cited is

700 fruits per tree per year, each averaging 1–4 kg. An

average of 200 fruits per tree, each weighing from 1 to

2 kg, has been estimated for the Caribbean. Yields for

the South Pacific are generally given as 50–150 fruits

per tree per year, although a study in Pohnpei

recorded from 212 to 615 fruits per tree depending

on the cultivar. Hectare yield estimates range from 16

to 50 tons based on 100 trees ha

1

. Mature breadnut

trees in the Philippines have been reported to produce

600–800 fruits per season. The average number of

seeds per fruit is variable, ranging from 32 to 94 per

fruit, each seed weighing an average of 7.7–10 g.

Based on 100 trees ha

1

, each average 200 fruits per

tree, an average yield of 11 MT ha

1

of fresh seeds

has been estimated.

Composition and Use

Seeds

0019 The seeds of breadfruit and breadnut have a thin,

dark-brown outer skin about 0.5 mm thick and an

inner, fragile paper-like membrane which surrounds

the fleshy white edible portion of the seed. Seeds are

firm, close-textured, and have a sweet pleasant taste

that is most often compared to chestnuts. The small,

immature fruits of breadnut are sliced and cooked as

vegetables, seeds and all. Seeds are harvested from

ripe fruits and boiled or roasted with salt. Breadfruit

seeds are usually cooked with the raw breadfruit or

are boiled or roasted. They generally are smaller than

breadnut seeds and sometimes have a slightly bitter

flavor.

0020The nutritional composition of breadnut and

breadfruit seeds is shown in Table 1. The seeds, espe-

cially breadnuts, are a good source of protein and are

low in fat, compared to nuts such as almond, brazil

nut, and macadamia nut. The fat extracted from

the seed is a light yellow, viscous liquid at room

temperature with a characteristic odor similar to

that of peanuts. It has a chemical number and

physical properties similar to those of olive oil.

Seeds are a good source of minerals and contain

more niacin than most other nuts. Four amino acids

(methionine 3.17 g, leucine 2.6 g, isoleucine 2.41 g,

fig0006Figure 6 Using long-handled poles to harvest breadfruit from a

20-year-old tree.

BREADFRUIT 659

and serine 2.08 g) comprised 50% of 14 amino acids

analyzed.

Fresh Fruits

0021 Breadfruit is a versatile food that can be cooked and

eaten at all stages of maturity, although it is most

commonly consumed when mature but still firm,

and is used as a starchy staple. The relatively bland

fruit can form the basis for an array of dishes, and it

takes on the flavor of other ingredients in the dish.

Very small fruits, 2–6 cm or larger in diameter, can be

boiled and have a flavor similar to that of artichoke

hearts. These can be pickled or marinated. Mature

and almost mature breadfruit can be boiled and sub-

stituted for potatoes in many recipes. Ripe fruits are

very sweet and can be eaten raw or used to make pies,

cakes, and other desserts. In the Philippines, candied

breadfruit is made by boiling slices in coconut and

sugar.

0022 Breadfruit’s carbohydrate content is as good as or

better than that of other widely used major carbohy-

drate foods. Compared to other staple starch crops, it

is a better source of protein than cassava and is com-

parable to sweet potato and banana. It is a relatively

good source of iron, calcium, potassium, riboflavin,

and niacin. A comparison of nutrient composition of

fresh and fermented mature fruits, and breadfruit

flour is shown in Table 2. The nutritional compos-

ition of breadfruit varies among cultivars and should

aid in the selection of cultivars for different uses for

fresh consumption and processed products.

0023 Fruit quality and attributes Fruit texture is an im-

portant attribute that affects cooking and processing.

Seedless and few-seeded breadfruit both exhibit a

wide range of textures at the mature stage. Preferred

fruits are generally those that are dense, smooth, and

creamy when cooked. There are cultivars with mealy

flesh, as well as ones with fibrous, stringy flesh, and

spongy ones which are full of what appear to be fine

threads of latex. The quality of cooked fruit also

depends on the method of preparation: different cul-

tivars provide different results when boiled, roasted,

or baked. Some cultivars are suitable for roasting but

become mushy and fall apart when boiled. The po-

tential for wide-scale processing by freezing, canning,

or production of flour will be enhanced by selection

of suitable cultivars. The presence or absence of seeds

will affect how fruits are handled and processed.

Fruits with seeds are probably inappropriate for

large-scale canning or chip-making operations but

are excellent for home use because they are a good

source of protein and make breadfruit a more com-

plete food.

Postharvest Handling

0024A major limitation on the greater utilization of bread-

fruit is the seasonal nature of the crop – the trees

typically bear fruits for just several months of the

year – and the highly perishable nature of the fruit.

Small-scale commercial processing of breadfruit in-

volves canning slices in brine in Jamaica for local and

export markets. Breadfruit flour and chips have been

made on a limited basis, and the flour has been evalu-

ated as a substitute for enriched wheat flour and as a

base for instant baby food. The starch has been ex-

tracted and may find use in industrial applications

such as textile manufacture.

0025The keeping quality of breadfruit is limited by a

rapid postharvest rate of respiration, with the fruits

typically ripening and softening in just 1–3 days after

harvest. Breadfruit’s perishability restricts local

marketing and limits its export potential since fruits

ripen before they reach their destination. Shelf-life

can be extended by several days by careful harvesting

and precooling fruits with chipped ice in the field and

during transport. Refrigeration markedly increases

shelf-life for both untreated fruits and ones stored in

sealed polyethylene bags. However, fruits show symp-

toms of chilling injury at temperatures below 12

C.

Satisfactory fruit quality is best maintained at

12–16

C with a shelf-life of 10 days for unwrapped

fruits and 14 days for packaged fruits. Controlled-

atmosphere storage has good possibilities. Fruits kept

tbl0002Table 2 Proximate composition of breadfruit per 100 g edible

portion

Fresh

a,b,d

Flour

c,e

Fermented

a

Water (%) 63.8–74.3 2.5–19.0 67.3–71.2

Protein (g) 0.7–3.8 2.9–5.0 0.7

Carbohydrate (g) 22.8–77.3 61.5–84.2 27.9

Fat (g) 0.26–2.36 1.93 1.13

Calcium (mg) 15.2–31.1 50 42.0

Potassium (mg) 352 1630 20–399

Phosphorus (mg) 34.4–79.0 90

Iron (mg) 0.29–1.4 1.9 0.73–1.18

Sodium (mg) 7.1 2.8

Thiamin (mg) 0.07–0.12

Riboflavin (mg) 0.03–0.1 0.2

Niacin (mg) 0.81–1.96 2.4

Ascorbic acid (mg) 19.0–34.4 22.7 4–20

b-carotene 0.01 0.04–0.29

Data from

a

Aalbersberg WGL, Lovelace CEA, Madhoji K and Parkinson SV

(1988) Davuke, the traditional Fijian method of pit preservation of staple

carbohydrate foods. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 21: 173–180;

b

Dalessandri KM and Boor K (1994) World nutrition – the great breadfruit

source. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 33: 131–134;

c

Graham HD and Negron

de Bravo E (1981) Composition of the breadfruit. Journal of Food Science 46:

535–539;

d

Murai M, Pen P and Miller CD (1958) Some Tropical Pacific Foods.

Honolulu: University of Hawaii;

e

Wootten M and Tumalii F (1984) Breadfruit

production, utilisation and composition. A review. Food Technology in

Australia 36: 464–65.

660 BREADFRUIT

at 16

C in atmospheric containers of 5% carbon

dioxide and 5% oxygen remained firm for 25 days

with some browning of the skin.

0026 Cooked breadfruit can be frozen, and this storage

method deserves greater attention as it may provide a

simple, effective means to utilize this crop better.

Small sections of fruit which have been boiled for

2–5 min compare most favorably in flavor, color,

and texture of fresh cooked breadfruit and can be

kept at 15

C for 10 weeks or more. Sections of

fruit that are frozen without first being boiled dis-

color on cooking after storage and have poor flavor.

0027 Since breadfruit is generally preferred while mature

and still firm, nutritional studies, development of

commercial products, and research to extend shelf-

life have focused on this stage. Ripe fruits generally go

to waste or are used as animal food, and there has

been little attention given to expanding the use of ripe

fruits. A greater proportion of the breadfruit crop

could be utilized and marketed if food products in-

corporating ripe breadfruit, such as baby foods,

baked goods, and desserts, are developed. Breadfruit

is a reliable, easy-to-grow, nutritious staple food

which has the potential to be more widely grown

and used in the world’s tropical regions. This can

best be accomplished by selecting cultivars that

extend the fruiting season and developing better

methods of postharvest handling and simple, eco-

nomical means of processing the fruits.

See also: Fermented Foods: Origins and Applications;

Figs; Fruits of Tropical Climates: Commercial and

Dietary Importance; Preservation of Food

Further Reading

Aalbersberg WGL, Lovelace CEA, Madhoji K and Parkin-

son SV (1988) Davuke, the traditional Fijian method of

pit preservation of staple carbohydrate foods. Ecology

of Food and Nutrition 21: 173–180.

Coronel RE (1983) Rimas and Kamansi. In: Coronel

RE(ed.) Promising Fruits of the Philippines, pp. 379–

398. Los Banos: College of Agriculture, University of

the Philippines at Los Banos.

Dalessandri KM and Boor K (1994) World nutrition – the

great breadfruit source. Ecology of Food and Nutrition

33: 131–134.

Graham HD and Negron de Bravo E (1981) Composition

of the breadfruit. Journal of Food Science 46: 535–539.

Leakey CLA (1977) Breadfruit Reconnaissance Study in the

Caribbean Region. CIAT/InterAmerican Development

Bank.

McIntoch C and Manchew P (1993) The breadfruit in

nutrition and health. Tropical Fruits Newsletter 6: 5–6.

Murai M, Pen P and Miller CD (1958) Some Tropical

Pacific Foods. Honolulu: University of Hawaii.

Narasimhan P (1990) Breadfruit and jackfruit. pp. 193–

259. In: Nagy S, Shaw PE and Wardowski WF (eds)

Fruits of Tropical and Subtropical Origin. Composition,

Properties and Uses, pp. 193–259. Lake Alfred, Florida:

Florida Science Source.

Negron de Bravo E, Graham HD and Padovani M (1983)

Composition of the breadnut (seeded breadfruit). Carib-

bean Journal of Science 19: 27–32.

Quijano J and Arango GJ (1979) The breadfruit from Co-

lombia – a detailed chemical analysis. Economic Botany

33: 199–202.

Ragone D (1997) Breadfruit. Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson)

Fosberg. Promoting the Conservation and Use of Under-

utilized and Neglected Crops. 10. Institute of Genetics

and Crop Research, Gatersleben/International Plant

Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy.

Roberts-Nkrumah LB (1993) Breadfruit in the Caribbean:

a bicentennial review. Extension Newsletter. Dept. of

Agriculture, Univ. of the West Indies (Trinidad and

Tobago). Tropical Fruits Newsletter. 24: 1–3.

Wootten M and Tumalii F (1984) Breadfruit production,

utilisation and composition. A review. Food Technology

in Australia 36: 464–465.

BREAKFAST AND PERFORMANCE

C Ani and S Grantham-McGregor, University

College London, London, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 Breakfast is the first main meal of the day. As

the name suggests, it is a meal taken after a long

period of overnight ‘fasting.’ Starting the day without

breakfast has been likened to embarking on a long-

distance drive with an empty fuel tank. In this article,

we will discuss what constitutes an adequate break-

fast, and review the evidence for the effect of

breakfast on children’s cognitive performance and

school achievement. We will also explore some of

the possible mechanisms underlying these effects. Al-

though there is no precise standard of what an ad-

equate breakfast should contain, it is generally

recommended that it should provide between

BREAKFAST AND PERFORMANCE 661

20 and 25% of the recommended dietary allowance

of energy and other nutrients. In western countries,

the widespread fortification of breakfast products

(e.g., cereals) with vitamins and minerals means that

eating an adequate breakfast usually increases the

chances of meeting daily micronutrient requirements.

Many school-aged children miss breakfast or have

inadequate breakfast. Children from poor or disor-

ganized families are at high risk of missing breakfast,

as are children of working mothers. In developing

countries, children may have to walk long distances

to school as well as do household or farming work

before going to school and thus use a considerable

amount of energy before arriving at school. Therefore

eating breakfast is likely to be particularly important.

0002 Studies from several western countries show that

skipping breakfast is common among adolescent

girls. For example, 30% of 14–15-year-old girls in a

Swedish study skipped breakfast. This trend has been

blamed on efforts by young girls to fit ‘desirable’

body images portrayed by the media. Although the

obvious goal for skipping breakfast is to limit calorie

intake, paradoxically, skipping breakfast may actu-

ally increase overall daily calorie intake by increasing

the likelihood of eating more at lunch, or relieving

hunger with higher-fat snacks.

0003 An important question is, does missing breakfast

affect children’s ability to achieve in school? Several

studies have shown that children who usually miss

breakfast have poorer cognition and school achieve-

ment than children who eat breakfast. However,

missing breakfast is often associated with poverty

and disorganized families, which may independently

affect children’s function. Therefore the best evidence

of the effect of eating breakfast comes from experi-

mental studies in which children are given breakfast

or asked to miss it. We will first review evidence for

breakfast affecting children’s cognition, including

attention, memory, and problem-solving.

Breakfast and Cognitive Performance

0004 The short-term effects of having or missing breakfast

have been examined in several studies conducted in

schools. In these, children who had breakfast were

compared with those who did not have breakfast on

tests of cognitive performance. The results were in-

consistent. A possible explanation is that the studies

had no control over the children’s prior diet and

activity and there were no baseline measures before

treatment to compare with after-treatment measures.

The most rigorous experiments have been done in a

laboratory setting, where the effect of missing or

receiving breakfast was examined in the same

children in a crossover design. Children were given

cognitive tests on the mornings when they received

breakfast and when they did not, and their perform-

ance was compared. The studies achieved tight con-

trol over the children’s prior diet and activity by

admitting them overnight to the laboratory before

the experiments. The rigor of the studies was im-

proved by random assignment of children to receive

breakfast or placebo on the first occasion. Two such

studies in the USA found that the children’s perform-

ance on cognitive tests improved when they received

breakfast. In two other studies in Jamaica and Peru,

undernourished children’s cognition deteriorated

when they missed breakfast whereas well-nourished

children were not affected.

0005It appears that the quality of breakfast is also

important. One study from Sweden using a crossover

design found that children who received adequate

breakfast (e.g., cereal, yogurt, sandwiches, and milk)

performed better in tests of creativity and addition as

well as physical exercise compared with those who

ate inadequate breakfast (e.g., sweet rolls and sweet

drink).

0006In a Jamaican study conducted in schools, children

were given breakfast at school regardless of whether

they had it at home. The study had a crossover design

and all children were tested after 1–2 weeks of receiv-

ing breakfast and after not receiving breakfast. In

spite of loss of control over previous diet and activity

the findings were similar to the previous Jamaican

study. The undernourished children showed benefits

in their performance on cognitive tests on the morn-

ings when they received breakfast.

0007In summary, the evidence from the best-controlled

studies indicates that missing breakfast or having

an inadequate breakfast affects children’s cognitive

performance especially if they are already under-

nourished.

How Can Breakfast Affect Cognitive

Performance?

0008The cognitive effects of breakfast are likely to be

mediated by several factors. The relief of hunger

may play a role. Children who miss breakfast may

suffer short-term hunger during midmorning school

work. Hungry children may be easily distracted and

undermotivated and thus not attend to learning tasks.

Eating breakfast can relieve these adverse effects of

hunger on children, thereby improving the children’s

ability to learn.

0009Second, the nutritional components of breakfast

may have direct metabolic benefits on cognition. In

particular, glucose or its precursors is thought to be

important. Several studies in elderly subjects, young

adults, and children have found that glucose drinks

662 BREAKFAST AND PERFORMANCE

improve memory and concentration. Reaction times

and driving ability have also been improved with

glucose drinks. In one study, memory in people who

ate breakfast correlated with their levels of blood

glucose. Another study showed that a glucose drink

improved the memory of those who missed breakfast

to the same level as those who had eaten breakfast.

However, a glucose drink did not improve memory

any further in those who had eaten breakfast. This

finding suggests that beyond a certain threshold of

blood glucose level, higher levels of intake confer no

extra cognitive advantage. Interestingly, glucose did

not improve all cognitive functions in subjects

who missed breakfast and recall of a story was not

improved with glucose. The findings suggest that,

while glucose may explain some of the cognitive

benefits of breakfast, it does not account for all of

them.

0010 In order for glucose to influence mental perform-

ance, there should be a biochemical mechanism

linking it with mental function. Such a link is thought

to exist through the role of glucose in the biosynthesis

of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter associated with

memory. Acetylcholine is synthesized from choline

and acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), and glucose is

the major substrate for the synthesis of acetyl-CoA. It

has been shown that increased glucose levels can

enhance the synthesis of acetylcholine and that giving

glucose can ameliorate falling levels of the neuro-

transmitter. Animal studies have also shown that

giving glucose ameliorates the loss of memory pro-

duced by drugs that inhibit acetylcholine. While glu-

cose plays a role in some of the short-term cognitive

benefits of eating breakfast, other nutrients (e.g.,

protein, energy, iron, iodine, etc.) may contribute to

mental performance in the medium to long term.

0011Millions of children in developing countries are

underweight and short for their age (stunted). These

children generally have poorer cognitive function

than adequately nourished children. Several studies

of children under 3 years have shown that nutritional

supplementation improves concurrent mental devel-

opment and in some cases long-term development.

We are unaware of long-term supplementation

studies beginning at an older age. Micronutrient

deficiencies, including iron, iodine, and zinc, have

also been implicated in causing poor cognition in

school-aged children. So providing an adequate

breakfast containing protein, energy, and micronu-

trients over a long period of time should improve

undernourished children’s nutritional status and

thereby improve their cognitive development.

Breakfast and School Performance

0012School achievement depends on three main factors,

including the children’s innate cognitive ability and

biological state, school characteristics such as the

quality of teaching and availability of reading mater-

ials, and home factors such as parental educational

level and their attitude to school. The amount of time

children spend engaged on a task is a critical deter-

minant of whether they learn the task. Time on task

depends not only on the amount of time actual teach-

ing occurs but also on the children’s attendance and,

when present, if they are actively engaged in a task or

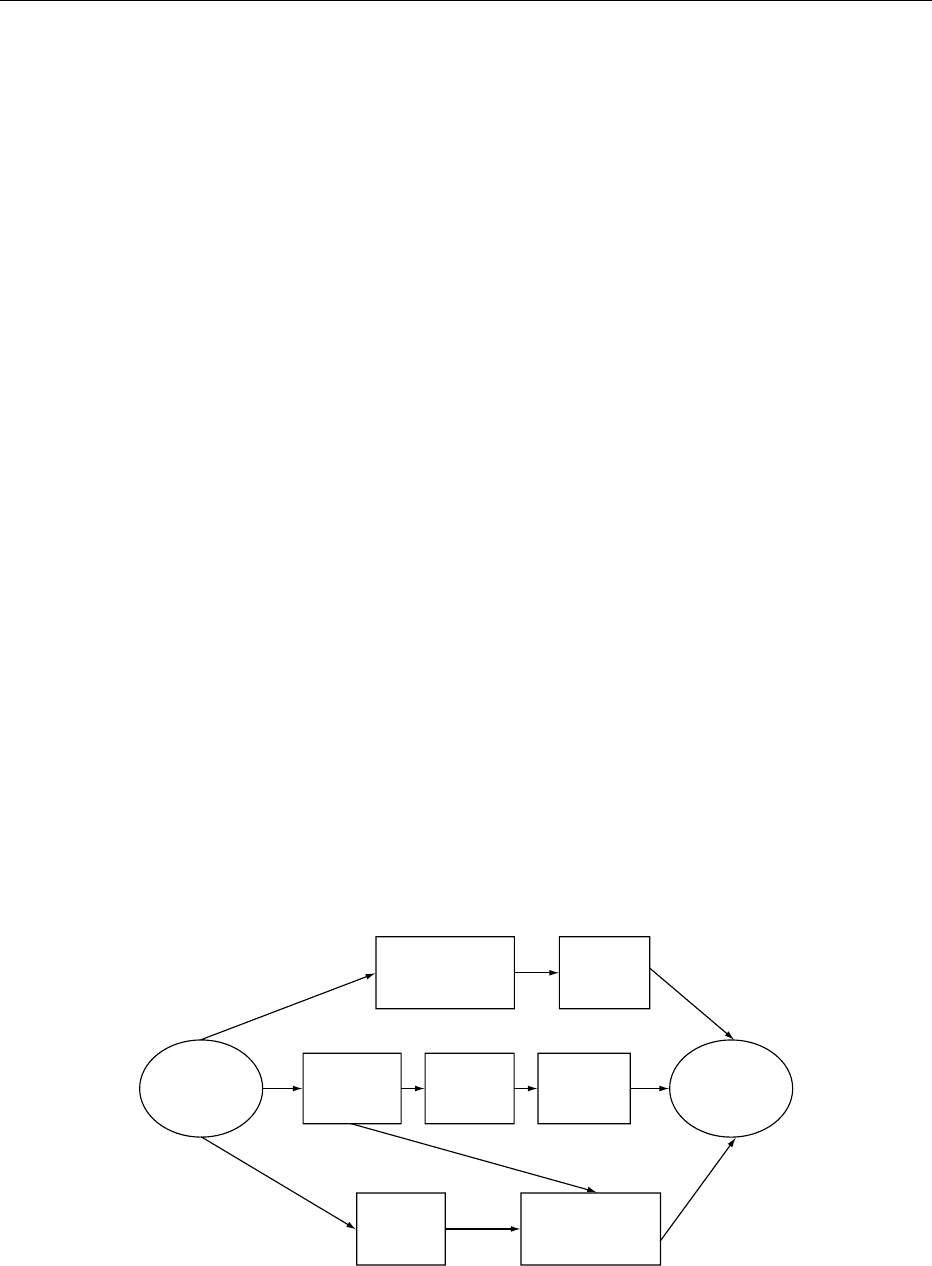

distracted. As shown in Figure 1, there are several

ways breakfast (especially when provided in schools)

could improve school performance. First, as discussed

above, eating breakfast is likely to prevent midmorn-

ing hunger and improve children’s cognitive ability.

In addition, it may improve classroom behavior,

Better enrollment,

punctuality, and

attendance

More time

in school

School

breakfast

Less hunger

Improved

behavior

More time

on tasks

Better school

achievement

Improved

nutritional

status

Improved memory,

cognition, and

attention

fig0001 Figure 1 Mechanisms for the effects of breakfast on school performance. Adapted with permission from Ani C and Grantham-

McGregor SM (1999) The effects of breakfast on educational performance, attendance and classroom behavior. In: Donovan N and

Street C (eds) Fit for School. How Breakfast Clubs Meet Health, Education and Childcare Needs, pp. 14–22. London: New Policy Institute.

BREAKFAST AND PERFORMANCE 663

including reducing disruptive behavior and improv-

ing concentration. The opportunity to eat breakfast at

school may also encourage children to attend school

more frequently, particularly in situations where food

is short at home. The children may also be more

punctual if they want to eat breakfast before school

begins. All these factors may increase the time the

children spend actively engaged on learning tasks.

0013 In addition, where undernutrition is prevalent,

children who eat adequate breakfasts regularly are

more likely to become well nourished and to perform

better in school. We will now review studies examin-

ing the relationship between breakfast, classroom

behavior, and school achievement.

Classroom Behavior

0014 Although early studies reported improvements in

children’s classroom behavior when they were given

breakfast, they were generally poorly designed,

making interpretation difficult. The measurements

were often subjective and depended on reports from

teachers, who were aware of whether the children

had been given breakfast. There are a few more recent

and better-designed studies. These studies have

shown when children received breakfast they were

off-task and out of their seats less often, and partici-

pated more actively in teaching activities and showed

better peer interaction. However, the situation is com-

plicated and, in a Jamaican study, children’s behavior

in response to receiving a school breakfast varied

according to the atmosphere and organization of the

classroom. In well-organized classrooms their behav-

ior improved with breakfast but in poorly organized,

overcrowded classrooms their behavior actually

deteriorated and they were out of their seats more

often and less on-task.

0015 One study showed that children who were pro-

vided with a glucose drink were more attentive and

showed fewer signs of frustration when given a

difficult task.

School Attendance

0016 In the USA, it has been shown that students partici-

pating in the Department of Agriculture School

Breakfast Program were more likely to attend and

less likely to be late to school compared with non-

participants. Other studies in poorer countries like

Peru and Jamaica have also consistently found

improved attendance among participants in school

breakfast programs.

School Achievement

0017 There are few well-designed evaluations of school

breakfast programs; most have failed to have control

groups or pretreatment measures. Low-income stu-

dents who participated in a school breakfast program

in the USA were found to perform better in tests of

mathematics, reading, and language compared with

nonparticipating students from similar backgrounds.

In a randomized controlled trial in Jamaica, students

given breakfast over two school terms performed

better in arithmetic compared with those who

received a low-calorie drink. Another study in Peru

showed that the vocabulary of nutritionally at-risk

students improved when given school breakfast for

as little as a month, compared with similarly disad-

vantaged but nonparticipating children. However, the

effects of breakfast on school achievement have not

been studied more than one school year, so it is

unknown whether the improvements continue.

Overall Conclusions

0018There is good evidence that missing breakfast detri-

mentally affects children’s cognitive function, espe-

cially if they are undernourished. Glucose benefits

cognition in children who have missed breakfast and

there is some suggestion that the short-term effects of

breakfast on cognition may be partly but not wholly

explained by the metabolic effect of glucose. In under-

nourished populations, long-term benefits could be

mediated by improvements in nutritional status.

0019There is also good evidence that if breakfast is

provided at school in high-risk populations, the chil-

dren’s attendance and punctuality improve. There is

some evidence that classroom behavior and school

achievement also improve. However, there is a need

for more rigorous studies in both developing and

developed countries and the long-term benefits need

to be evaluated. In view of the demonstrable benefits

of breakfast to children’s performance, policy-makers

should consider implementing school breakfast

programs in high-risk populations.

See also: Carbohydrates: Requirements and Dietary

Importance; Eating Habits; Glucose: Function and

Metabolism; Hypoglycemia (Hypoglycaemia);

Malnutrition: The Problem of Malnutrition

Further Reading

Ani C and Grantham-McGregor S (1999) The effects of

breakfast on educational performance, attendance and

classroom behavior. In: Donovan N and Street C (eds)

Fit for School: How Breakfast Clubs meet Health,

Education and Childcare Needs, pp. 14–22. London:

New Policy Institute.

Benton D and Parker PY (1998) Breakfast, blood glucose,

and cognition. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

67: 772S–778S.

664 BREAKFAST AND PERFORMANCE