Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

under these conditions differ from those produced by

conventional mixers, where mixing is accomplished

more by pressure than stretching. The resistograph

has a mixing head that combines blending with

stretching, pressing, and kneading. It imparts a high

work input to the dough and can be used for the

evaluation of dough response to high-speed mixing.

Strong flours show a sharp increase in mixing resist-

ance, and broadening and narrowing of the band. The

resistograms of medium strength and weak flours are

characterized by two pronounced maxima. The first

is related to waterbonding and dough development

and indicates the dough development time. The

second measures the stickiness and extensibility at

breakdown of the dough; the time to reach this

point is most important in testing medium and weak

flours. Both optimum and breaking points are

reached when the blades of the mixer are completely

covered with dough.

Load–Extension Tests

0040 Several commercial instruments are available for the

routine testing of dough at large elongations. From

the recorded curves, various characteristics, such as

resistance to deformation, extensibility, and energy

needed to rupture the dough, can be computed.

Among these instruments, the Brabender extensi-

graph is the most common. It was developed in

about 1936 as a supplement to the farinograph,

and has become particularly useful in the study

of the effect of various chemical improvers on the

rheological properties of dough. The extensigraph

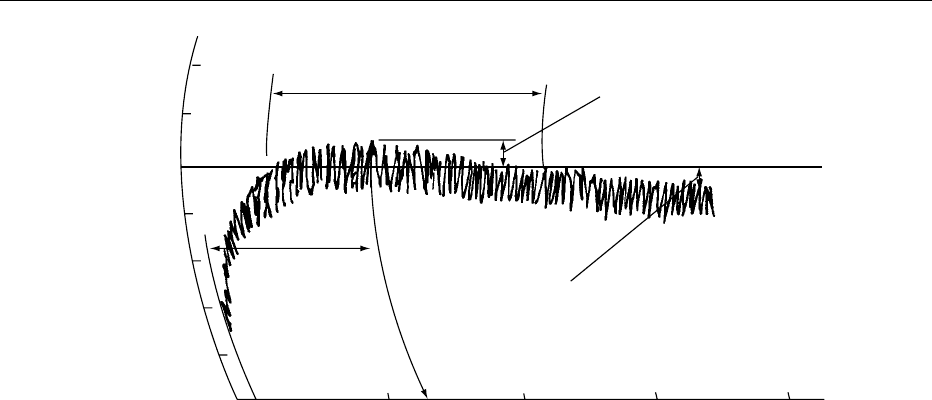

data (Figure 5) reported for control purposes are

usually the curve length in centimeters (extensibility),

the curve height in extensigraph units either at the

maximum or 5 cm from the start of the curve (resist-

ance), the area under the curve in square centimeters

(strength value), and the quotient of height over

length – the greater this quotient, the stronger the

dough. Several attempts have been made to use the

extensigraph for more fundamental studies, and to

transform extensigraph data into rheological terms.

The main problem in these transformations is the

calculation of the actual cross-sectional area based

on the ‘effective mass’ of the dough, i.e., the mass

between the edges of the cradle supporting the dough.

The effective mass progressively increases during

stretching because some dough is pulled out from

the cradle due to its resistance to extension. The

effective mass and the actual cross-sectional area of

the dough can be calculated from multiple regression

equations. The coefficient in these equations, how-

ever, change with the type of dough and have to be

determined experimentally.

0041A higher sensitivity and wider applicability of the

Brabender extensigraph may be achieved by replacing

the mechanical recording device by an electronic

strain gauge system.

0042Another load–extension meter used in cereal

laboratories is the research extensometer (Halton

extensigraph) designed by Halton and associates.

While the actual extensometer works on a similar

principle to the Brabender extensigraph, the required

water content for dough preparation is measured on

500

0

0 5 10 15 20

Stability

Mixing tolerance index

(5 mm after peak)

Degree of softening

(12mm after peak)

Time (min)

Consistency (BU)

Dough

development

time

fig0004 Figure 4 Representative farinogram showing the most commonly measured parameters. Brabender units (Bu) are a measure of

optimum consistency of the dough. From Bloksma AH (1971) Rheology and chemistry of dough. In: Wheat Chemistry and Technology.

St. Paul, MN: American Association of Cereal Chemists, with permission.

BREAD/Dough Mixing and Testing Operations 625

the principle of extrusion by means of a special water-

absorption meter, which, together with a mixer/

shaper, belongs to the three-unit extensometer. The

interpretation of the curves is the same as with Bra-

bender extensigrams. A great advantage of this instru-

ment lies in its applicability to fermenting doughs.

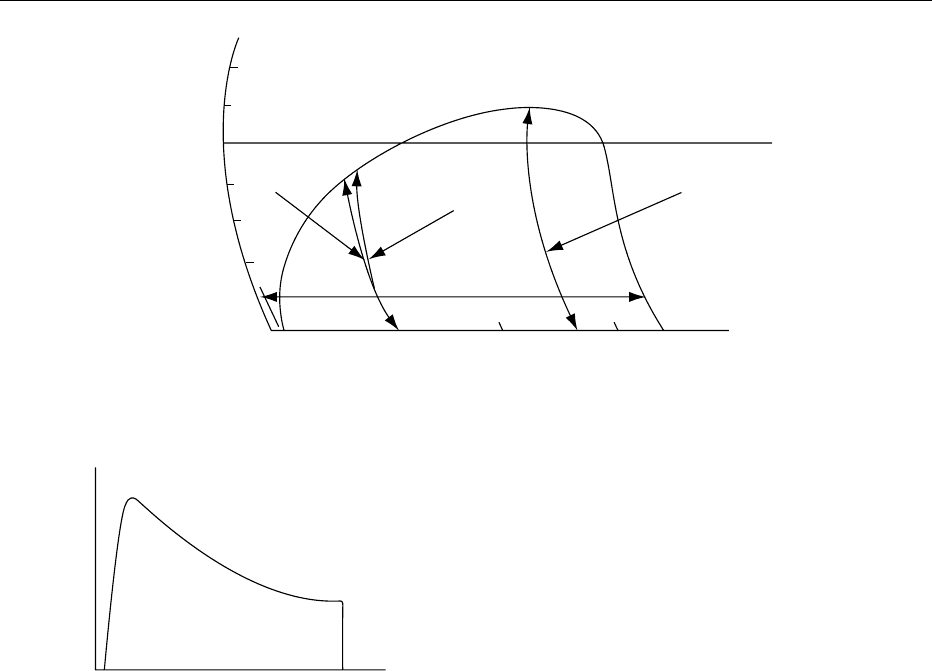

0043 The Chopin alveograph is more popular in Europe

than in North America. The instrument consists of

three parts: mixer, bubble blower, and a recording

manometer. The procedure involves using air pressure

to blow a bubble from a disk of sheeted dough until it

reaches its breaking point. A recording manometer

records the presure of the air in the bubble as a

function of time. The manometer records a curve

(Figure 6) from which three basic measurements are

taken: the height and the length of the curve, and the

area under the curve. The area under the curve is

proportional to the work of deformation.

Viscosity Measurements

0044 The third step in the process of the physical testing of

flour or dough, based on the ‘three-phase concept of

bread baking,’ is the measurement of changes in flour-

paste viscosities at temperatures above the gelatiniza-

tion temperature of starch present in flour. The data

obtained by these measurements are not only related

to the gelatinization characteristics of the crumb in

the baking oven, but also a good indicator of the

diastatic activity of the flour. These measurements

do not fall into the category of dough rheology, be-

cause all tests are done on flour slurries only. How-

ever, they help to evaluate factors that considerably

affect the consistency of dough as well as the texture

of bread crumb, its color, general appearance, and

shelf-life. The most common instrument used for

these tests is the Brabender amylograph. It is a torsion

viscometer that provides a continuous record of

changes in viscosity of the flour slurry at a uniform

rate of temperature increase (decrease) of 1.5

C

min

1

under constant stirring. Although the instru-

ment was originally developed for testing rye-flour

pastes, the amylographic method has become a stand-

ard method for controlling a-amylase activity in

wheat flour. The higher the activity, the lower the

hot paste viscosity due to the liquefying effect of

the enzyme. The effect of other amylolytic enzymes

present is also reflected in the amylogram.

See also: Biscuits, Cookies, and Crackers: Methods of

Manufacture

Further Reading

AACC (1969) Approved Methods, 8th edn. St. Paul, MN:

American Association of Cereal Chemists.

Bloksma AH (1971) Rheology and chemistry of dough.

In: Wheat Chemistry and Technology. St. Paul, MN:

American Association of Cereal Chemists.

Chichester CO, Mrak EM and Schweigert BS (1984) Dough

properties and mixing behaviour. In: Advances in Food

Time (minutes)

Pressure

fig0006 Figure 6 Representative alveogram. From Bloksma AH (1971)

Rheology and Chemistry of dough. In: Wheat Chemistry and Tech-

nology. St. Paul, MN: American Association of Cereal Chemists,

with permission.

R⬘

5

R

5

R

m

Resistance

Corrected

resistance

Extensibility

Time (minutes)

Maximum resistance

500

0

Force (BU)

fig0005 Figure 5 Representative extensigram showing the most commonly measured parameters. From Bloksma AH (1971) Rheology and

chemistry of dough. In: Wheat Chemistry and Technology. St. Paul, MN: American Association of Cereal Chemists, with permission.

626 BREAD/Dough Mixing and Testing Operations

Research, vol. 29, pp. 230–234. London: Academic

Press.

De Man JM, Voisey PW, Rasper VF and Stanley DW (1975)

Empirical methods in physical dough testing. In:

Rheology and Texture in Food Quality, pp. 310–323.

Westport, CT: AVI.

Khatkar BS, Bell AE and Schofield JD (1995) The dynamic

rheological properties of glutens and gluten sub-

fractions from wheats of good and poor breadmaking

quality. Journal of Cereal Science 22: 29–44.

Khatkar BS and Schofield JD (1997) Molecular and

physico-chemical basis of breadmaking – properties

of wheat gluten proteins: A critical appraisal. Journal

of Food Science and Technology 34(2): 85–102.

Kilborn RH and Tipples KH (1972) Factors affecting mech-

anical dough development. I. Effect of mixing intensity

and work input. Cereal Chemistry 49: 34–47.

Kilborn RHI and Tipples KH (1973) Factors affecting

mechanical dough development. IV. Effect of cysteine.

Cereal Chemistry 50: 70–86.

MacRitchie F (1992) Physico-chemical properties of wheat

proteins in relation to functionality. Advances in Food

Nutrition Research 36: 1–87.

Quillen CS (1954) Mixing – the universal operation.

Chemical Engineering 61: 177–224.

Ravi R and Haridas Rao P (1995) Factors influencing the

response of improvers to commercial Indian wheat

flours. Journal of Food Science and Technology 32:

36–41.

Shewry PR, Halford NG and Tatham AS (1994) Analysis of

wheat proteins that determine breadmaking quality.

Food Science and Technology 8: 31–36.

Sidhu JS (1999) Effect of improvers and hydrocolloids

on rheological and baking properties of wheat flour.

Ph.D. thesis, GND University, Amritsar, India.

Sidhu JS and Bawa AS (1998) Effect of gum acacia on

rheological properties of wheat flour. Journal of Food

Science and Technology 35: 157–159.

Sidhu JS, Singh J and Bawa AS (1999) Effect of carboxy

methyl cellulose on the rheological gas formation and

gas retention properties of wheat flour. Journal of Food

Science and Technology 36: 139–141.

Sidhu JS, Singh J and Bawa AS (2000) Effect of incorpor-

ation of sodium alginate on rheological, gas formation/

retention and baking properties of wheat flour. Journal

of Food Science and Technology 37: 79–82.

Stauffer CE (1990) Oxidants. In: Stauffer CE (ed.) Func-

tional Additives of Bakery Foods, pp. 1–41. New York:

Von Nostrand Reinhold.

Torikata Y and Ban N (1994) Intelligent mixer for bread

dough. In: Developments in Food Engineering. Part I,

pp. 266–267. Glasgow: Blackie Academic and Profes-

sional.

Valentas KJ, Levine L and Clark JP (1991) Dimensional

analysis – mixing and sheeting of doughs. In: Food

Processing Operations and Scale-up, pp. 359–361.

New York: Marcel Dekker.

Voisey PWand Kilborn RH (1974) An electronic recording.

Grain Research Laboratory mixer. Cereal Chemistry 51:

841–848.

Breadmaking Processes

M Collado-Ferna

´

ndez, University of Burgos, Burgos,

Spain

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001Bread is one of the most consumed food products

known to humans, and for some people, it is the

principal source of nutrition. Bread is an inexpensive

source of energy: it contains carbohydrates, lipids,

and proteins, and it is important as a source of essen-

tial vitamins of the B complex and of vitamin E,

minerals and trace elements.

0002The history of bread can be traced back about

six millennia. Breadmaking is an ancient art that is

closely connected with the development of the human

race and civilization, but the development of the

baking oven, the industrial production of baker’s

yeast in the nineteenth century, was decisive for the

technology of breadmaking. The twentieth century

led to technical advances and the rationalization of

bread production. Some of these advances in bread-

making include knowledge about physical–chemical

changes in dough, the rheology of flour and dough,

and the development of different instrumentations of

rheology. Research into breadmaking is currently

concerned with staling, the influence of the different

additives on the breadmaking process, and the rheo-

logical properties of flour, dough, and bread, in order

to improve its quality.

0003There are numerous variations of the breadmaking

process. The choice of one or another is related to:

tradition, cost, the kind of energy available, the kind

of flour, the kind of bread required, and the time

between baking and consumption of bread.

Bread

0004The basic formulation of bread is wheat flour, yeast,

salt and potable water. Optional ingredients are

nonwheat flours, shortening, nutritive carbohydrate

sweeteners, skim-milk powder, enzyme active prepar-

ations, dough conditioners, and so on. The Food and

Drug Administration legally defined the specified

amounts of these optional ingredients in the produc-

tion of various standardized bread products. (See

Legislation: Additives.)

0005Bread is the food produced by baking a dough

obtained by mixing wheat flour, salt, and potable

water, leavened to specific microorganisms of bread

fermentation, as Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Each

country has many different kinds of bread, and these

differ from one country to another (bread, rolls, pan

BREAD/Breadmaking Processes 627

bread, pita bread, French bread, toast bread,

baguette, etc.).

0006 The breadmaking process changes the rheological

and organoleptic properties of bread; this also

changes the quality. In each country, the definition

of quality may also change according to specific con-

sumer preferences. However, the term ‘bread’ de-

scribes a range of products of different shapes, sizes,

textures, crust, colors, softness, eating qualities, and

flavors. For this reason, we will consider only the

influence of the breadmaking process on the organo-

leptic properties of bread, and not if this bread is of a

good or bad quality. The principal attributes of bread

are as follows: loaf volume, crumb softness, grain

uniformity, silkiness of texture, crust color, flavor

and aroma, softness retention, and nutritive value.

Although the breadmaking process influences the

end product, the bread, the principal influence is the

quality of different ingredients and especially the kind

of flour used.

Principal ingredients

Flour

0007 The breadmaking quality of flour depends on the

variety of the grain, all agricultural and climatic

conditions, including the harvest, and the milling

process. Flour is the major ingredient in most formu-

lations. The most important characteristics of flour

are as follows: the protein content, especially the

quantity and quality of gluten, the water absorption

capacity, and the diastatic activity. The kneading

of the flour and water gives the dough a cohesive,

viscoelastic mass that retains the gas formed during

fermentation. Thus, flour is responsible for the struc-

ture of bread. (See Flour: Analysis of Wheat Flours.)

Yeast

0008 The principal function of yeast is the conversion of

the simple sugars into carbon dioxide and ethanol.

The production of gas causes the expansion of dough.

Yeast also has an important role in the rheological

propertiesof dough.(See Bread:DoughFermentation.)

Salt

0009 Salt is used in all baked goods to provide flavor, and

because of its effect on the breadmaking process,

salt has an influence on the rheological properties of

dough. Salt inhibits the hydration of gluten; the

gluten shrinks, the dough does not collapse, and gas

retention is improved. Higher concentrations of salt

inhibit enzymatic reactions and also inhibit the fer-

mentation activity of yeast. In general, the proportion

of salt used is 1–2% (based on flour weight).

Water

0010Only potable water may be used for the production of

bread, and its quality is very important in breadmak-

ing. Mineral constituents of the dough water (mainly

carbonates and sulfates) give a firmer, more resistant

gluten; the doughs do not collapse during fermenta-

tion, the gas retention is improved, and with a normal

volume, the grain is finer and more elastic.

Optional Ingredients

Fat

0011The use of fats is essential to be able to keep the bread

in storage. The functions of fats are as follows: fat

increases the shelf-life, produces a finer grain, and, if

used in small concentrations, yields a greater volume

of baked foods (10%). The crust is more elastic and

softer. The shortening effect is due to the formation of

a film between the starch and protein layers of the

flour. Surface-active materials, such as mono and

diglycerides or lecithin, promote the formation of

this film of fat and have a fat-sparing effect. The

shortening effect is greater for fat with a lower

melting point than for harder fats. The best fats are

hydrogenated vegetable fats with a solidifying point

between 30 and 40

C. Fat produces a dough with

more plasticity, so the use of fat requires less water in

the formulation.

Sugar

0012Sugar promotes fermentation, browning of the crust,

and a sweeter taste. In addition, it makes the dough

more stable, more elastic, and shorter, and the baked

goods more tender. For increasing additions of sugar

and fat, the amount of added liquids must be reduced

for a given dough consistency.

Milk and Dairy Products

0013These include milk (usually skim-milk powder) and

whey containing lactose, which promotes browning,

a softer crust, and a longer shelf-life.

Oxidants

0014The function of oxidants is the oxidation of -SH

groups of protein to -SS-groups, resulting in an im-

provement in rheological properties of dough and of

gas retention. The disulfide bonds thus established

within and between protein chains lead to a firmer

gluten structure. The time of dough maturation is

shorter, the oven spring is greater, the volume is

large, and the quality of the grain is better. The

oxidant commonly used is ascorbic acid (E300). (See

Legislation: Additives.)

628 BREAD/Breadmaking Processes

Enzyme Active Preparations

0015 Flours with a low enzyme activity produce breads

that do not brown well, have a crumbly crumb, and

stale rapidly. Such flours must have fermentable

sugars or enzyme active preparations added (malted

flour, malt extract, and bacterial or fungal a-

amylases). The addition of malted flour increases

bread volume slightly; the texture is better and de-

creases the keyholing (especially of pan breads). The

addition of a -amylases is most important to start the

hydrolysis of starch and to form the substrate for b-

amylase action. The addition of fungal or bacterial a-

amylases makes a difference to the thermal stability.

The heat stability of bacterial a-amylases is higher.

These amylases often remain active after baking and

may cause some problems (moist and slim crumb)

in the final product. (See Enzymes: Functions and

Characteristics.)

Emulsifying Agents

0016 Emulsifying agents or shortening or tensoactive

agents are used to make bread softer during storage,

especially pan bread. The effect of emulsifying agents

on dough and baked products is based on their reac-

tion with the starch–protein–fat–water system. The

dough improves the strength of the gluten structure

and improves the handling characteristics of dough as

well as gas retention, and staling is delayed. Some of

the emulsifiers in use are monoglycerides (E471),

esters from monoglycerides and diacetyltartaric acid

(DATA esters; E472e), sodium or calcium stearoyl-2-

lactylate (SSL, E481 or E482), lecithin (E322), and

other ingredients that perform a similar function.

(See Fats: Uses in the Food Industry; Legislation:

Additives.)

Preservatives

0017 Preservatives are used in bread with a higher moisture

content (40%) and packed hermetically because these

breads are more sensitive to mold growth. The most

important preservatives are calcium propionate

(E282), sorbic acid (E200), and vinegar to prevent

mold growth or rope. Calcium propionate also affects

the fermentation process. More yeast can be added

to compensate for this effect. (See Legislation:

Additives.)

Breadmaking Process

0018 The elaboration of bread may be divided into three

principal stages:

1.

0019 Kneading of Dough (Dough formation): This

stage marks the difference between all the bread-

making processes. In general, the kneading of

dough involves the thorough mixing of ingredi-

ents. Some ingredients such as gluten and starch

are hydrated; others are dissolved in water. The

mechanical work produced by mixers contributes

energy to the development of a gluten, incorpor-

ates air bubbles within the dough, and produces a

dough with the rheological properties required,

such as viscosity, elasticity, extensibility, gas reten-

tion, etc.

2.

0020Fermentation, Proofing, or Proving: Fermentation

is the action of the yeast on fermentable sugars to

produce carbon dioxide (CO

2

) and ethanol (which

has a neutral taste). The gas is retained by dough

and increases its volume. The production of gas

and gas retention depends on the quality of the

flour. The modifications of this stage are con-

trolled fermentation and ultrafrozen dough.

3.

0021Baking: This is the last stage, where, by the action

of heat, the dough is converted into the final baked

products by firming (stabilization of the structure)

and by the formation of the characteristic aro-

matic substances. A modification of this stage is

prebaked bread.

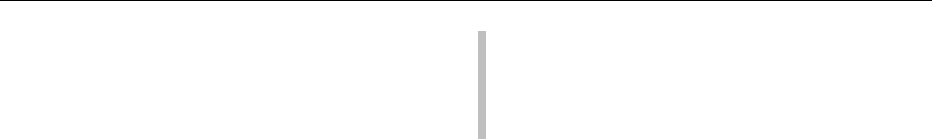

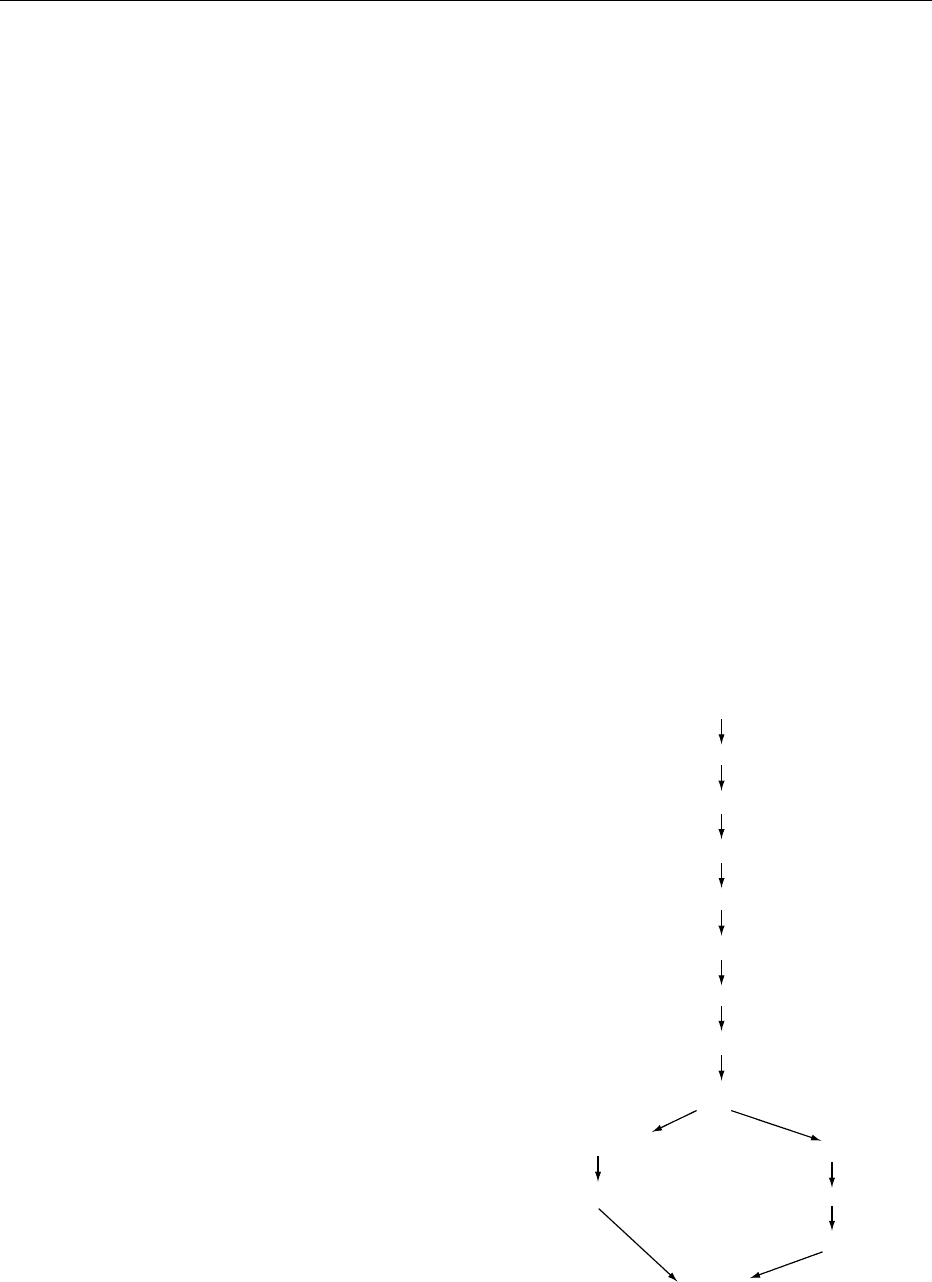

0022The different steps in breadmaking are as follows

(Figure 1):

Ingredients (flour, water, salt, yeast)

Mixing

Kneading (dough formation)

First fermentation or first proof

Dividing

Rounding

Molding

Fermentation, final proof

Baking

Final preparations

Cooling

Slicing

Packing (bagging)

Storage

fig0001Figure 1 Different steps in the breadmaking process.

BREAD/Breadmaking Processes 629

.0023 Ingredients: Depending on the kind of bread re-

quired (flour, water, salt, yeast). (See Flour: Analy-

sis of Wheat Flours.)

.

0024 Kneading: This stage makes the greatest differ-

ence between all the breadmaking processes. (See

Bread: Dough Mixing and Testing Operations.)

.

0025 First Fermentation or First Proof: Dough has a

resting period (floortime) in bulk after mixing

and before dividing. In general, this stage tends

to be substituted by intensive kneading or by

other methods. Its function is to adapt the fer-

mentation agent to the medium, production of

dioxide carbon and other components, and the

physical transformation of dough. The duration

of this stage depends on the kind of process and

equipment. The temperature conditions are

27

C, relative humidity 75% (to avoid dried

surfaces), and draught-free.

.

0026 Dividing: Dough may be divided by weighting or

volumetrically (which is more common). At this

stage, dough must be fluid, and have plegability

and extensibility. After dividing, the dough is

degassed and has an irregular form, the surface of

dough has a higher viscosity, the structure of gluten

has been damaged and the surface does not retain

gas, and the dough has less plegability. For this

reason, dough needs to undergo the next operation,

rounding.

.

0027 Rounding: Dough with a rotary motion produces a

ball-shaped piece with smooth skin. The alveolar

structure is redistributed and improves the reten-

tion of gas. Dough is less viscous. After rounding,

dough needs a floortime (between 2 and 20 min) in

order to increase the plegability. The temperature

conditions are 27–29

C. If the temperature

increases, dough becomes stale, decreases the

retention of gas, and becomes more sticky; if the

temperature decreases, dough becomes colder,

and the fermentation time is greater. The relative

humidity is 75%; if the relative humidity increases,

this also increases the stickiness of dough.

.

0028Molding: Two successive steps are responsible for

the final shape of dough: laminated and curled. The

molded dough is placed either in tins or on a baking

tray and kept in a proofing cabinet to continue

fermentation (final proof). This step is necessary

to work the fermented dough, divide the alveolus,

and provide a uniform redistribution.

.

0029Fermentation, Final Proof, or Proving: During

fermentation, starch is converted into sugars by

enzyme action. The sugars feed the yeast, and the

breakdown products are carbon dioxide and etha-

nol. As carbon dioxide is produced, the dough

expands and retains it, and it is important that the

skin remains flexible. There is a relationship be-

tween produced and retained gas that depends on

the quality of the gluten structure. The more

retained gas, the more bread volume. The tempera-

ture used depends on the kind of bread and the

breadmaking process (28–30

C): the lower the

temperature, the longer fermentation time (2–4h

or 1–1.30 h). The relative humidity is between 60

and 90%, depending on the formulations and fer-

mentation temperature. There is a variation of P/L

during fermentation; dough has less tenacity (P)

and more energy (w). (See Bread: Chemistry of

tbl0001 Table 1 Comparison of breadmaking processes

Breadmaking

process

Mixing Kneading Fermentation Mixer Dividing Rounding First proof Molding Second

proof

Oven

Straight Dough

Method

Yes 20 min Bulk 2–4 h No Yes Yes 10–20 min

floortime

Yes 70–80 min Yes

Sponge and

Dough

Process

Sponge or

predough

No Sponge 4 h Yes, and dough

stage

Yes Yes 20 min Yes 60 min Yes

Poolish Preferment

liquid

No Preferment

1–2 h

Yes Yes Yes 20 min Yes 60 min Yes

System

Do-Maker

Preferment

without

flour

No Preferment

2.5 h

Mixer

developer

No No No Panning 60 min Yes

Amflow

System

Preferment

with flour

No Preferment

2h

Mixer

developer

No No No Panning 60 min Yes

Chorleywood

Process

High-speed

mixer

2 min 30 s No No Yes Yes 15 min Yes 50 min Yes

ADD Yes 20–25 min No No Yes Yes 15 min Yes 50 min Yes

Source: Kulp K and Ponte JG (2000) Handbook of Cereal Science and Technology, 2nd edn. New York: Marcel Dekker; Quaglia G (1992) Scienza e tecnologia

della panificazione. Pinerolo: Chiriotti Editori;

Rehm HJ and Reed G (1983) Baked goods. In: Biotechnology: a Comprehensive Treatise,Vol. 5: Food and Feed Production with Microorganisms, pp. 1–83.

Weinheim: Verlag Chimie.

630 BREAD/Breadmaking Processes

Baking; Dough Mixing and Testing Operations;

Dough Fermentation; Sensory Evaluation: Aroma.)

.

0030 Baking: Baking is the final operation. There are

physical, chemical, and biological transform-

ations in dough that allow a stable product to

be obtained, with excellent organoleptic and nu-

tritive characteristics, the bread. (See Bread:

Dough Mixing and Testing Operations; Sensory

Evaluation: Aroma.)

.

0031 Final Preparations: Different steps for retention

of quality: cooling, slicing, and packing.

.

0032 Cooling: During cooling, the moisture of the crumb

goes to crust. It is necessary to reduce the tempera-

ture gradually to maintain the bread quality, and to

take into account the relative humidity and tem-

perature. If the relative humidity is low, the bread

will lose too much moisture and may have no uni-

form crust. If the relative humidity is high, the crust

of the bread will not be crunchy. This step is very

important to maintain the bread quality when

bread needs to be sliced and packed.

.

0033 Slicing: The bread must be cold for slicing; if not, it

will crumble.

.

0034 Packing: Packing maintains the product quality by

reducing crumb drying, minimizes the risk of con-

tamination, and gives an appealing and informative

package to the consumer.

Description of Breadmaking Processes

0035 The different breadmaking systems are related to the

diverse methods for making the dough. Although

there are numerous variations, the major processing

methodologies or breadmaking process are as

follows:

Straight Dough Method

0036 Flour, water, yeast, salt, and all other ingredients are

added at the same time by single-stage mixing into a

dough of optimum physical properties (i.e., the soft-

ness and appearance required, as well as the elasti-

city). The amount of water required depends on the

water adsorption capacity of the flour determined by

the farinograph. Usually, the amount of water is

about 55–60% of the flour weight. (See Bread:

Dough Mixing and Testing Operations.)

0037 The kneading time depends on the speed and type

of mixers used as well as the flour characteristics.

Strong flours need more kneading time than soft

flours. The speed differs, and energy imparted to the

dough has repercussions on the efficiency of mixing

of ingredients. (See Bread: Dough Mixing and Testing

Operations.)

0038 The dough is removed from the mixer, which may

have a temperature between 26 and 28

C, and is kept

in the proof cabinet to ferment for 2–4 h, depending

on the concentration of the yeast used. Afterwards,

the dough is divided, rounded, molded, fermented

(final proof), and baked.

.

0039Advantage: It requires less processing time, labor,

power, and equipment. Fermentation losses are

smaller than with other processes.

.

0040Disadvantage: Relatively small variations in pro-

cessing may lead to noticeable variations in the

final quality of breads. It is less flexible than the

sponge dough, requires limited fermentation time,

and does not permit correction of overfermenta-

tion.

0041Straight dough breads have a blander flavor than

sponge dough breads. They do not have a soft texture,

and the bread volume is lower, but this depends on the

quantity of additives used.

Sponge and Dough Process

0042This method is the most common manufacturing

commercial process used in the USA. In this indirect

process, the flour, water, and a portion of the yeast are

first mixed into a sponge or predough (temperature

25

C). When the predough has fully fermented, it is

mixed with the remaining flour, water, and other

ingredients to make the final dough (temperature

26–28

C), which is then given a short fermentation.

Afterwards, the dough is divided, rounded, molded,

fermented (final proof), and baked. (See Bread: Sour-

dough Bread.)

0043This method permits the use of strong and soft

(weak) flour, using the strong flour to make the

sponge and the soft in the final dough. Usually, the

amount of strong flour is about 50%.

0044For rich dough high in fat or sugar, the fermenta-

tion time is often only 20–30 min. In this case, all the

yeast is used with one-fourth to one-third of the flour

and water to form a warm, soft predough. This causes

better swelling and acclimatizes the yeast to the con-

ditions of the dough.

.

0045Advantage: It permits greater variations in the op-

erations of the process and improves the volume,

texture, and shelf-life of the bread. In addition, the

longer fermentation time improves the aroma.

.

0046Disadvantage: It requires more fermentation time

and labor than the straight dough method, and it is

more difficult to control. Sometimes, the dough has

more tenacity, and it is difficult to divide, laminate,

and mold.

Liquid Fermentation Process (Poolish)

0047The principle of this process is essentially the same as

the sponge and dough method, except that it uses a

BREAD/Breadmaking Processes 631

liquid instead of solid sponge. Its origin is Poland,

hence the name Poolish, or liquid sponge. This

method has been used since the 1920s with some

variation in Vienna (for the production of Viennese

bread); and in France (for the production of French

bread). It has been used in American bakeries since

the 1950s. (See Bread: Sourdough Bread.)

0048 These preferments contain flour, water, and yeast.

Usually, the amount of water is 1 l per kilogram of

flour, and the amount of yeast depends on the fermen-

tation time (12–15 g of yeast to 3 h; 7–8 g of yeast to

6 h; and 5 g of yeast to 8 h). The temperature of

fermentation is 23–31

C. The fermented liquid is

stirred slowly to prevent foaming. After the desired

fermentation time (the liquid triples its volume), the

liquid is cooled by a heat exchanger to 8–10

C

and kept in a refrigerated storage tank until used. It

may be stored for a 24-h period without any loss of

activity.

0049 The second step is the addition to this preferment

liquid of the remainder of the flour, water, and salt

(1%) and the other ingredients in the formulation.

Afterwards, the final dough is fermented for 1 h,

and then the remaining operations in the breadmak-

ing process continue: dividing, rounding, molding,

fermentation (1 h), and baking.

.

0050 Advantage: The same as the sponge and dough

process, and also the consistency of the liquid

sponge permits its transfer by pumping and better

control of the production process. It permits work

with weak flours, increasing its energy and elasti-

city, a cause of better starch gelatinization, and

it has a good machinability. It requires less pressed

yeast, and a single preferment may be used for

the production of a variety of breads and baked

goods.

.

0051 Disadvantage: It requires more fermentation time

and labor than the straight dough method.

Continuous Bread Process

0052 The development of continuous mix processes started

in 1926 with the observation that the enzymatic and

oxidative changes in dough structure during fermen-

tation may be replaced by intensive mixing of dough

at a high rpm. This process, introduced in the USA in

the 1950s, was represented by two systems: the ‘Do-

Maker’ process, based on patents granted to John

C. Baker, and the ‘Amflow’ process, introduced by

the American Machine and Foundry Co. It was

observed that high-speed mixing could not replace

the development of CO

2

and the aroma substances

during fermentation. High-speed mixing was used

with a liquid preferment to insure a desirable aroma

in the final bread.

0053Do-Maker system (preferment liquid without

flour) All operations are automatic. The first phase

consists of preparations of the preferment liquid,

which is a solution with all ingredients except the

flour and shortenings (sugar, yeast, and nutrients to

yeast and water). The development of the dough is

due to the high degree of mechanical work, and not to

floortime. It is also necessary to add higher levels of

oxidants. The fermentation requires 1–4 h (usually

2.5 h) at 30–32

C, with constant slow stirring in a

vertical tank. The liquid preferment is then cooled

(4

C) and can be stored for a long time. During the

fermentation, the pH decreases, so liquid preferment

buffer substances like soya flour and powdered milk

are added.

0054The second phase involves mixing the liquid prefer-

ment with the flour, shortening, and oxidants for 30–

60 s and then pumping it to the developer. Usually, the

rate of addition of the ingredients is 18–19 kg min

1

for flour and 14 kg min

1

for the preferment. The

dwell time in the developer is only about 60 s. It is

then extruded into pans.

.

0055Advantages: The bread has a very uniform and fine

grain, with a very soft crumb and a thin crust. It

requires less time than the other systems with bulk

fermentation.

.

0056Disadvantages: The taste of the bread is different

from that of the conventional sponge and dough

bread.

0057Amflow system (liquid preferment with flour) This

system is similar to the Do-Maker, except that the

preferment is formed with flour, and the tank is

horizontal.

0058Obtaining the preferment is a double step. In the

first step, water, yeast, yeast nutrient, and a portion of

sugar are mixed and kept in a holding tank to ferment

for 1 h, and the aroma is developed. In the second

step, salt, skim-milk powder, additional sugar, and

12% of flour are added. This viscous liquid is pumped

to another tank for a second fermentation for 1 h with

slow stirring at 30–32

C. Finally, the preferment

(sponge liquid) is pumped into a horizontal tank and

cooled. The sponge liquid is pumped into the pre-

mixer, where the remaining ingredients (flour, water,

sugar, fat, and oxidant) are mixed. This mixture is

then developed in the mixer-developer. It is necessary

to decrease the pressure created in the dough in order

to avoid excess air, and directly extrude into baking

pan. The bread has a very fine grain.

No-time Doughs (Short-time Doughs)

0059Dough fermentation and dough maturing may be

accelerated by the addition of reducing and oxidant

632 BREAD/Breadmaking Processes

substances. This has led to the development of ‘no

time dough’ in which dough maturation is obtained

by mechanically and chemically decreasing the

fermentation stage.

0060 Chorleywood process This system is also known as

‘mechanical dough development’ and ‘intensive

kneading.’ This process originated in the UK and is

used extensively throughout the world. The character-

istic of this process is mixing of the dough intensively

in a batch, high-speed mixer (Tweedy kneader) for 3–

5 min with a controlled energy input. The optimum

work input is 11 Watt-hours per kilogram of dough

(40 J g

1

). However, the energy requirements differ

for flours of varying quality (soft flour needs less

energy than strong flour) and the type of bread. This

energy is five to eight times the energy used in conven-

tional kneading. The mixing is generally done under

vacuum, so the dough must contain ascorbic acid (75

p.p.m.). In this process, it is necessary to add high-

melting-point fat (0.7% of flour), more water (3.5%)

to soften the dough, since it has to support excessive

mechanical work, and more yeast (50–100%).

.

0061 Advantages: This process saves time and space. The

bread may be ready in 1.30 h. The production of

bread is increased through the addition of extra

water, and wastage is reduced by absence of bulk

fermentation. Less, but more skilled, labor is neces-

sary. More conservation and less staling of bread

and soft flour may be used.

.

0062 Disadvantages: There is a reduction in the crumb of

bread, flavor, and aroma because of the shorter

processing times. For this reason, preferments

may be added.

0063 Activated dough development (ADD) This system

was developed after research carried out on the Chor-

leywood system. It was found that good bread could

be made with classic kneading, with a low-speed

kneader, and a similar time to kneading but with the

addition of chemical substances to eliminate the first

fermentation or bulk fermentation. In this system, it is

necessary to use fat and greater quantities of yeast

and water.

0064 Chemicals must be added before kneading, and are

as follows: l-cysteine hydrochloride (35 p.p.m. based

on flour) with ascorbic acid (35 p.p.m.) and potas-

sium bromate (25 p.p.m.). Some legislation does not

permit these oxidants. (See Legislation: Additives.)

.

0065 Advantages: This system is similar to the Chorley-

wood system, with the additional advantage of not

requiring a high-speed mixer. The cost of chemicals

is similar to the cost of the supplementary energy of

the high-speed mixer.

.

0066Disadvantages: The bread ADD crumb flavor and

aroma are worse than that of traditional bread

(straight dough) or Chorleywood bread.

0067In relation to fermentation, recent work has sought

to control fermentation, which permits the regulation

of bread production, and ultrafrozen dough. Con-

trolled fermentation is one of the new techniques

used to apply cold to stop or to decrease the extent

of fermentation. (See Bread: Dough Fermentation.)

0068In ultrafrozen dough, the fermentation is inter-

rupted for some time to renew it afterwards. The

prefermentation time must not be more than 15 min,

so as to avoid any type of fermentation. After

molding, the dough is ultrafrozen (35 to 40

C),

packed to avoid dry surface during conservation, and

stored at 20 or 18

C, until it is defrosted to go on

to fermentation and baking.

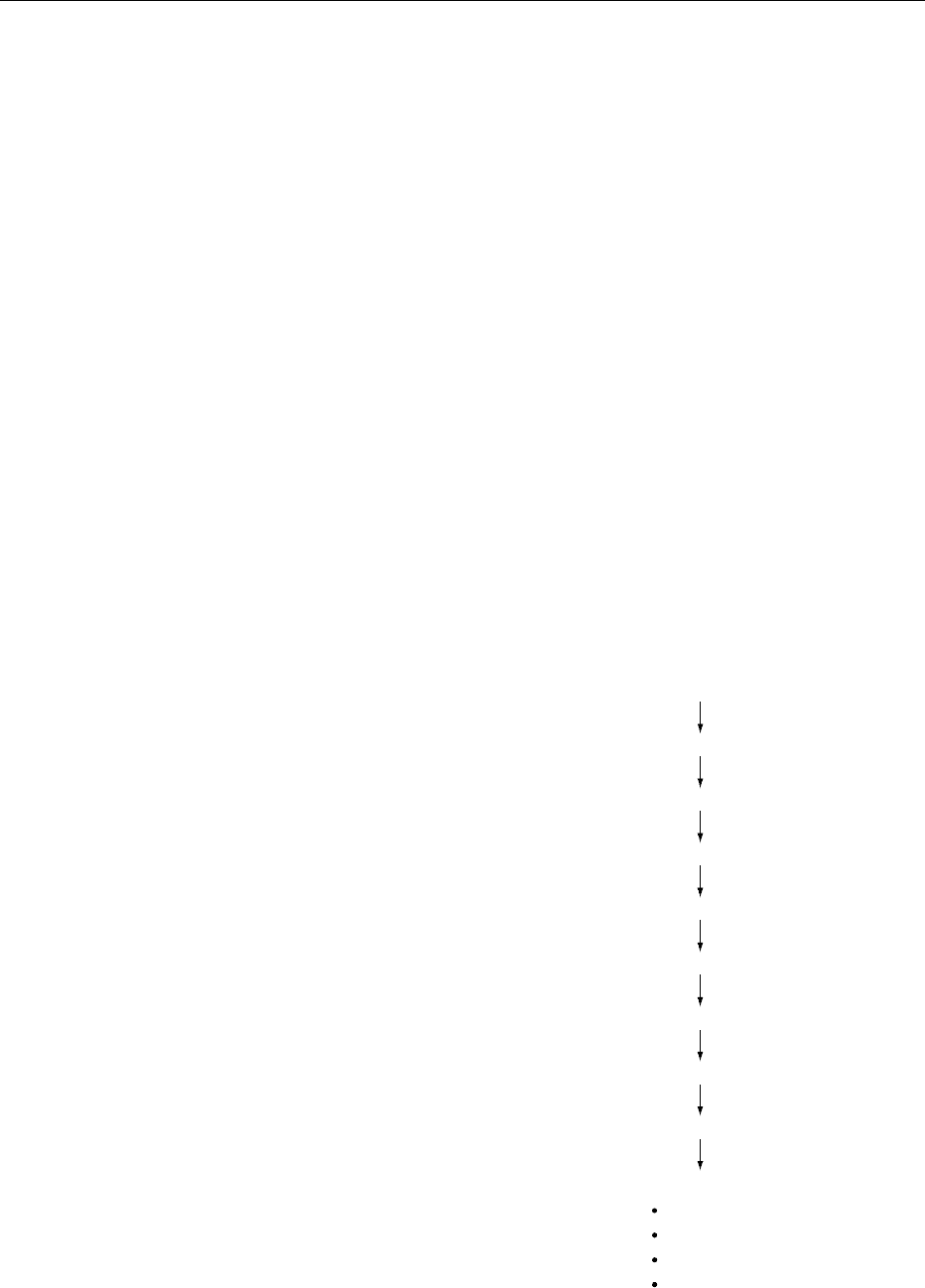

0069In relation to baking, recent research has investi-

gated prebaked bread. Prebaked bread is bread for

which baking has been interrupted and may be con-

tinued afterwards. The baking is divided into two

steps. The dough is prepared by the traditional

method and is placed into an oven for 10 or 15 min

until the starch has coagulated and the bread has

gained structure, and then the bread is taken out of

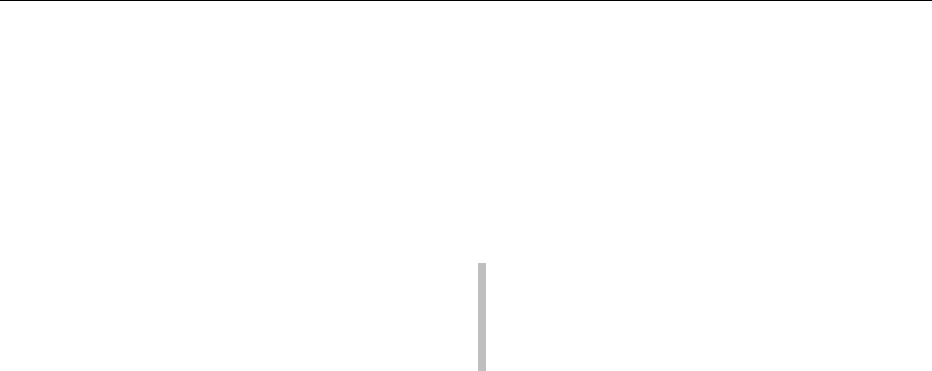

Ingredients (flour, water, salt, yeast, sour dough)

Mixing

Kneading

Dividing

Rounding

Molding

Fermentation

Prebaking (12 min)

Cooling (35−40 ⬚C)

Packing at modified atmosphere

Storing

Freezing (−40 ⬚C)

Storing (−15 ⬚C)

Defrosting

Baking (10−14 min)

fig0002Figure 2 Different steps in the prebaked bread process.

BREAD/Breadmaking Processes 633

the oven. After prebaking, the bread must be cooled

down for an hour to a temperature of 35–40

C,

without any draughts so as to avoid cracking the

crust, and packed in a modified atmosphere or frozen.

This bread has a white color, contains more moisture,

and is denser. The second phase is to finish the baking,

and then the bread looks exactly like traditional

bread.

.

0070 Advantages: Fresh bread can be obtained in a few

minutes without having to ferment previously.

.

0071 Disadvantages: The bread has less volume, the

crust is rougher and the crumb denser, and it stales

more rapidly compared with the traditional system

(straight dough).

See also: Bread: Dough Mixing and Testing Operations;

Chemistry of Baking; Sourdough Bread; Dietary

Importance; Dough Fermentation; Enzymes: Functions

and Characteristics; Fats: Uses in the Food Industry;

Flour: Analysis of Wheat Flours; Legislation: Additives;

Sensory Evaluation: Aroma; Yeasts

Further Reading

Cauvain SP and Young LS (1998) Technology of Breadmak-

ing, 1st edn. London: Blackie Academic & Professional.

Code of Federal Regulations (2000) Requirements for

Specific Standardized Bakery Products. Food and

Drugs Title 21 Part 136.110, pp. 347–349. Washington,

DC: Office of Federal Register, National Archives and

Records Administration. US Government Printing

Office.

Council of European Communities 89/107/CE (1989) Rela-

tiva a la aproximacio

´

n de las legislaciones de los estados

miembros sobre aditivos alimentarios autorizados en los

productos alimenticios destinados al consumo humano.

Official Journal of the European Communities Doce-n

049/1989 serie L.

Hoseney RC (1994) Principles of Cereal Science and Tech-

nology, 2nd edn. St. Paul, MN: American Association of

Cereal Chemists.

Kent N and Evers AD (1994) Technology of Cereals: an

Introduction for Students of Food Science and Agricul-

ture, 4th edn. Oxford: Pergamon.

Kulp K and Ponte JG (2000) Handbook of Cereal Science

and Technology, 2nd edn. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Lorenz KJ and Kulp K (1991) Handbook of Cereal Science

and Technology. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Pomeranz Y (1987) Modern Cereal Science and Technol-

ogy. New York: VCH.

Pomeranz Y (1988) Wheat: Chemistry and Technology, 3rd

edn. St. Paul, MN: American Association of Cereal

Chemists.

Quaglia G (1992) Scienza e tecnologia della panificazione.

Pinerolo: Chiriotti Editori.

Real Decreto 145/1997 (1997) Lista Positiva de Aditivos

distintos de Colorantes y Edulcorantes para su uso en la

elaboracio

´

n de productos alimenticios, ası

´

como sus

condiciones de utilizacio

´

n. In: Boletin Oficial del Estado

n

70, 22 de marzo, pp. 9378–9418. Madrid: Ministerio

de la Presidencia.

Rehm HJ and Reed G (1983) Baked goods. In: Biotechnol-

ogy: a Comprehensive Treatise, Vol. 5: Food and Feed

Production with Microorganisms, pp. 1–83. Weinheim:

Verlag Chimie.

Chemistry of Baking

M Collado-Ferna

´

ndez, University of Burgos, Burgos,

Spain

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001Baking is the last stage of the breadmaking process, in

which there are several physical–chemical and bio-

logical changes as the result of the action of heat.

These changes transform the dough into an edible

final product with excellent organoleptic and nutri-

tive characteristics – bread.

0002At this stage of baking, it is very important to

control the baking temperature and time, which

depend on the type of oven used, as well as the size

of pieces and the kind of bread desired (the formula-

tion used). All these possible variations may have

repercussions on the different quality of bread

depending on the bakery. The transfer of heat to

dough may be by conduction, convection, and radi-

ation. The different temperatures reached inside and

outside the dough cause the formation of the crust

and crumb of bread. The different phases during

baking are as follows: oven spring (enzyme active

zone), gelatinization of starch, and browning and

aroma formation.

Baking

Working Conditions

0003During baking, the following highly correlated

factors need to be controlled: the temperature of

baking, the type of baking oven, the relative humidity,

and the duration of baking.

Temperature of Baking

0004Usually, the baking temperature of 200–275

Cisa

function of the type of baking oven, the duration of

baking, and the size and type of bread desired (for-

mulation used). Generally, the small items require a

higher temperature and a shorter time, whereas large

items need a lower temperature and a longer time.

634 BREAD/Chemistry of Baking