Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Craighead LW, Stunkard AJ and O’Brien RM (1981) Be-

havior therapy and pharmacotherapy for obesity.

Archives of General Psychiatry 38: 763–768.

Dobbing J (ed.) (1989) Dietary Starches and Sugars in Man:

A Comparison. London: Springer-Verlag.

Legg C and Booth DA (eds) (1994) Appetite: Neural and

Behavioural Bases. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stunkard AJ (ed.) (1980) Obesity. Philadelphia: WB Saun-

ders.

Wadden TA, Sternberg JA, Letizia KA, Stunkard AJ and

Foster GD (1989) Treatment of obesity by very low

calorie diet, behaviour therapy, and their combination:

a five-year perspective. International Journal of Obesity

13 (suppl. 2): 39–46.

Sausages See Meat: Sources; Structure; Slaughter; Preservation; Eating Quality; Sausages and

Comminuted Products; Analysis; Nutritional Value; Hygiene; Extracts

Scallops See Shellfish: Characteristics of Crustacea; Commercially Important Crustacea; Characteristics of

Molluscs; Commercially Important Molluscs; Contamination and Spoilage of Molluscs and Crustaceans;

Aquaculture of Commercially Important Molluscs and Crustaceans

Scanning Electron Microscopy See Microscopy: Light Microscopy and Histochemical Methods;

Scanning Electron Microscopy; Transmission Electron Microscopy; Image Analysis

SCURVY

T K Basu, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta,

Canada

D Donaldson, Chemical Pathology Department,

East Surrey Hospital, Redhill, Surrey, UK

Copyright 2001, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Etymology

0001 ‘Scurvy’ is the current word in the English language

for what has at various times in history been referred

to as skurvie, scurvie, skirvye, scurvey, scurby, skyrby,

scorbie, and scorby. The same word, in varied forms,

has also been used to refer to scurf, i.e., dandruff.

Confusion has also arisen because one sign, the

petechiae (small hemorrhages in the skin), that are a

feature of scurvy and many hematological disorders,

has been referred to loosely and quite incorrectly as

scurvy, because they are confused with purpura. In

addition, many of the early references to scurvy are

almost certainly erroneous as only later was it pos-

sible to differentiate this clinical disorder from other

diseases of close or superficial resemblance. Further

confusion and lack of clarity were caused by reference

to patients with mixed disorders such as rickets as a

comorbidity as scurvy, when the disease might in

reality have been just a portion of the whole clinical

presentation. Scurvy is a clinical syndrome caused by

vitamin C deficiency which is associated with a de-

rangement of collagenous protein synthesis; this is

rapidly reversed with vitamin C supplementation.

History

0002The Ebers Papyrus from Ancient Egypt (c. 1500 bc)

contains a reference to what could well be scurvy. In

Ancient Greece Hippocrates referred to a disease oc-

curring in soldiers and comprising pain in the legs,

gangrene of the gums, and the consequent loss of

teeth. During the Middle Ages ‘land scurvy’ was

SCURVY 5107

recognized to be both commonplace and seasonal

throughout the whole of Europe, usually being seen

in the winter months, long after the cessation of

availability of summer fruits and vegetables.

0003 ‘Land scurvy’ became ‘sea scurvy’ during the 14th

and 15th centuries at the time of a rising spirit of

adventure, catalyzed by new technical developments

in ship design and advancements in navigational

instrumentation, and compounded by growing and

powerful commercial interests in the trading of silk

and spices. These factors cleared the way for longer

sea voyages of weeks or months in duration, without

the opportunity for the crew to land at ports where

fresh vegetables and fruits would be available. The

diaries of Commodore George Anson’s voyage of

1740–44, during which he attempted unsuccessfully

to circumnavigate the world and on which 1051 of

his 1955 men died – the majority from scurvy –

referred to the fact that ‘the scars of old wounds,

healed for many years, were forced open again’ and

stated ‘many of our people, though confined to their

hammocks, ate and drank heartily and were cheerful,

yet having resolved to get out of their hammock, died

before they could well reach the deck.’

0004 Vasco da Gama sailed from Lisbon on 9 July 1497

with about 140 Portuguese sailors. He reached the

south-eastern coast of Africa 7 months later; the

records indicated ‘many of our men fell ill here,

their feet and hands swelling and their gums grown

over their teeth so that they could not eat.’ On 6 April

1498 came the opportunity to purchase oranges from

Moorish traders. Just 6 days later it is stated ‘all our

sick recovered their health for the air of this place is

very good.’

0005 In the winter of 1536, on the frozen St Lawrence

River, the North American Indians taught the French

explorer Jacques Cartier and his men the value of

boiling the bark and leaves of the white cedar tree in

water and then drinking the juice and dregs. Three

doses on alternate days were sufficient ‘miraculously’

to cure their loss of strength and their swollen and

inflamed legs.

0006 The introduction of the potato to Europe from

South America, where it had been cultivated for

nearly 1500 years, was effected in the second half of

the 16th century by the Spaniards who invaded that

country. It is now seen to have provided a ready

means of combating the problem of low vitamin C

status in the winter months.

0007 In 1617 John Woodall, Surgeon-General of the Brit-

ish East India Company, wrote The Surgions Mate,

which contained a 23-page chapter on the subject of

scurvy. He emphasized at that time the necessity of

providing the crews of ships with the juice of oranges,

lemons, or limes. He added a recommendation of two

to three spoonfuls of lemon juice as a medicine

against scurvy, and as a preventive too, if enough

could be spared. This suggestion preceded the work

and publications of James Lind, which did not appear

until the following century.

0008James Lind was born in Edinburgh in 1716 and

eventually became Physician-in-charge of the 2000-

bed Haslar Hospital near Portsmouth, the largest and

newest of the naval hospitals, in which there was the

opportunity to study 300–400 cases of scurvy at a

time. The famous experiment of his earlier days, in

1747, involved six groups of two men each, treated as

follows: group 1 with cider, group 2 with elixir vitriol,

group 3 with vinegar, group 4 with sea water, group 5

with two oranges and one lemon each day over 6

days, and group 6 with garlic, mustard seed, balsam

of Peru, dried radish root and gum myrrh, together

with barley water, tamarinds and cremor tartar. All

received the same diet apart from the above ‘medi-

cines.’ The best response was from group 5 by the

sixth day, and group 1 came second at 2 weeks; the

other ‘remedies’ proved to be of no value. Lind pub-

lished his famous book A Treatise of the Scurvy in

1753, in Edinburgh. Nevertheless, it was not until

1804 that the Royal Navy decreed that lemon or

lime juice must be provided daily; limes were later

substituted for lemons as they were cheaper and could

be obtained from the new West Indian colonies, al-

though they are now known to contain less vitamin

C. Hence the origin of the term ‘limeys’ for British

sailors. In retrospect, one can now say that James

Lind made one major error in preparing his ‘rob of

oranges’ by evaporating juice down to 10% of its

original volume, as heat is now known to destroy

vitamin C; moreover, further storage following the

preparative procedures permits yet greater deterior-

ation in the vitamin C content.

0009The history of vitamin C is strewn with anecdotes

such as these. Others should be briefly mentioned;

they include Captain James Cook’s 1768 voyage to

the South Pacific in which his crew avoided scurvy by

his insistence on the consumption of various fresh

vegetables. An outbreak of scurvy at the National

Penitentiary at Millbank in London in February

1825, following drastic reduction of the diet of the

inmates, responded to the simple prescription of three

oranges a day; however, neither the kitchen staff nor

the prison officers suffered!

0010The Great Potato Famine of 1845–48 involved not

only the UK and Ireland but also France and Belgium;

many cases of scurvy were being reported in the Brit-

ish medical literature from 1847 onwards. Scurvy, not

surprisingly, was seen in the general population and

in the prisons and hospitals, too. The Royal Navy’s

Arctic expedition, which returned in 1876, suffered

5108 SCURVY

badly from scurvy in spite of the availability of lime

juice. However, lime juice had not been supplied on

sledging expeditions, and even when it had been

taken, the bottles had frozen solid, causing them to

break on thawing over the evening fire.

0011 In 1928 Albert Szent-Gyo

¨

rgyi isolated a sugar from

cabbage and lemon juice, and also from the adrenal

gland. He was not permitted by the editor of the

Biochemical Journal to call it ‘ignose’ or ‘godnose’

and had to call it ‘hexuronic acid’ instead. In 1932

CG King and WA Waugh identified the antiscorbutic

factor from lemon juice to be the same as hexuronic

acid; the name ascorbic acid was adopted. In 1933 Sir

Norman Hawarth and his colleagues in Birmingham,

UK, established the chemical structure of ascorbic

acid. Also in 1933 both Sir Norman Hawarth’s team

and the team led by Tadeus Reichstein in Switzerland

succeeded in synthesizing vitamin C.

0012 During the latter part of World War II, at the time

when many of those captured in the Far East were in

Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, it was accepted that

deficiency of vitamins A and B was commonly seen;

however, deficiency of vitamin C did not occur. The

reason for this was that the prisoners themselves pre-

pared and drank ‘jungle juice,’ a mixture of the green

leaf tops of sweet potatoes, kang kong (a vegetable

eaten by the local natives in Borneo), leaves of

the tapioca tree, and onion leaves for flavoring, all

boiled up quickly in water. Grass, which was in abun-

dance, and which is now known to contain weight-

for-weight more vitamin C than citrus fruits, was

never used as it was thought to have no nutritional

value.

Species-sensitivity

0013 Most animals do not develop scurvy since they are

able to synthesize vitamin C from glucose by the

reactions in eqns (1–3).

D-Glucose D-Glucuronic acid D-Glucuronolactone

D-Glucuronolactone L-Gulonolactone + O

2

2-Ketogulonolactone

2-Ketogulonolactone

L-ascorbic acid

gulonolactone

oxidase

+ H

2

O

2

NADPH.H

+

(2)

(1)

(3)

0014 The only known species unable to synthesize vitamin

C are the primates (including humans), guinea pigs,

the red-vented bulbul, the fruit-eating bat (Pteropus

medius), the rainbow trout and the coho salmon.

They lack the enzyme gulonolactone oxidase, which

is necessary for the conversion of l-gulonolactone to

l-ascorbic acid. Hence, these species are dependent

on dietary sources (Table 1) for the vitamin. (See

Ascorbic Acid: Physiology.)

Pathophysiology

0015Vitamin C deficiency causes failure to maintain the

cellular structure of the supporting tissues of

mesenchymal origin, such as bone, dentine, cartilage,

and connective tissues. As a consequence, vitamin C

deficiency is characterized by weakness and fatigue,

hyperkeratosis of the hair follicles, perifollicular

hemorrhages, petechiae and ecchymoses, swollen

bleeding gums, delayed wound healing, and the

easy fracturing of bone. These are the characteristic

clinical features of scurvy.

0016The clinical manifestations of scurvy are the result

of complete vitamin C deprivation of 100–160 days’

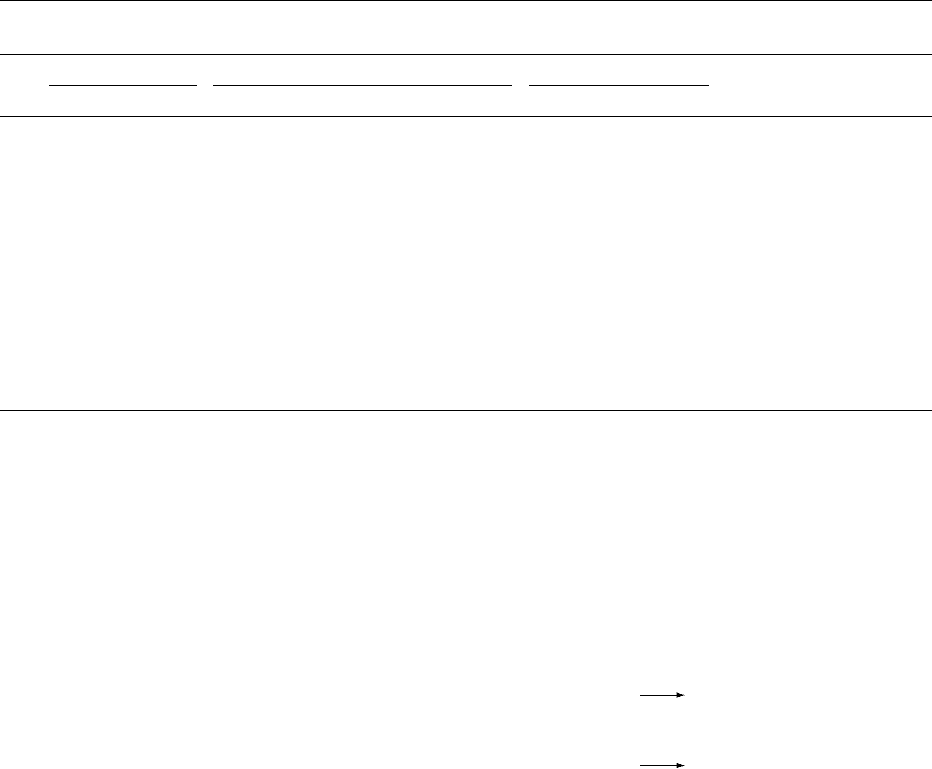

tbl0001Table 1 Vitamin C content of foods and plants

Food or plant Vitamin C content

(mg per 10 0 g or 10 0 ml)

Fruits

Apples 4

Banana with peel 7

Citrus fruits 25–60

Gooseberries, fresh 60–65

Strawberries 58

Vegetables

Broccoli 90

Cabbage

Fresh 45–60

Boiled 24–30

Peas

Sprouting 25–50

Dried 0

Potatoes

Uncooked 10–30

Baked in skin 15

Boiled 5–15

Boiled and reheated 2–8

Sauerkraut

Stored 1 month 10–15

Tomatoes 20

Animal origin

Adrenal glands 100–200

Eggs Trace

Meat or fish, well cooked Trace

Milk

Cows’, pasteurized 1

Human breast milk 30–55

Botanical

Scurvy grass 66–100

Spruce pine needles 65–200

Gramineae (grasses) 140–173

Liquids

Apple cider, fresh unpasteurized 4–5

Blackcurrant syrup 60

Lemon juice, fresh 45

Lime juice, fresh 30

Orange juice, fresh 48

Rosehip syrup 150–200

SCURVY 5109

duration (Table 2). During deficiency the vitamin C

pool of the body is depleted at a daily rate of about

2.6% of the existing pool; 92% is lost after 100 days

and symptoms of mild scurvy are evident when the

pool is less than about 300 mg.

0017 Fibroblasts play a central role in the wound-healing

process. In vitamin C deficiency the fibroblasts pro-

liferate but in an unimpeded manner. These prolifer-

ating cells generally remain immature, however, and

fail to synthesize collagen molecules, which are the

‘building blocks’ of tissue repair. The impaired fibro-

blastic activity is essentially responsible for the

delayed wound healing in vitamin C deficiency.

Moreover, in vitamin C deficiency cartilage cells of

the epiphyseal plate, at the end(s) of the diaphysis of

long bones, continue to proliferate and line up in

rows. The cartilage between these rows is calcified

where osteoblasts do not migrate, resulting in the

development of compressed and brittle bone.

0018 Ultrastructural studies in scurvy show distinct al-

terations of the ribosomal and polyribosomal pattern.

The endoplasmic reticulum shows considerable dila-

tion and loss of ribosomal granules. The polyribo-

somes are disaggregated, unbeaded fibrillar material

being seen in the extracellular space.

Biochemical Aspects

0019 The characteristic feature of scurvy is an inability of

the supporting tissues to maintain the synthesis of

collagen, the intercellular substance. The collagen

molecule consists of three linked popypeptide chains

of amino acid residues. For the collagen molecule

to aggregate into its triple helix configuration, the

proline and lysine residues of newly synthesized col-

lagen must be hydroxylated. Formation of the triple

helix is important because it is in this configuration

that the procollagen is secreted from the fibroblast.

Hydroxylation of both proline and lysine occurs after

the amino acids have been incorporated into the pep-

tide chain; vitamin C is required in these reactions.

The essential process mediated by vitamin C is the

formation of hydroxyproline from proline and of

hydroxylysine from lysine, as shown in the following

reactions:

Proline + ascorbate +O

2

OH-proline + Dehydroascorbate

Lysine + ascorbate + O

2

OH-lysine + Dehydroascorbate

proline hydroxylase

lysine hydroxylase

(5)

(4)

+ H

2

O

+ H

2

O

0020Vitamin C appears to act as a cofactor for peptidyl

proline and lysine hydroxylases, possibly by keep-

ing copper and iron in a reduced state. Defective

hydroxylation within the synthesizing fibroblast

gives rise to the formation of an abnormal collagen

precursor called protocollagen. Unlike the normal

precursor (tropocollagen), this substance may not be

extruded from the cell. If it is extruded it polymerizes

into an abnormal collagen which lacks tensile

strength. In addition to its requirement for collagen

synthesis, vitamin C is believed to be an essential

cofactor in forming the intercellular cement substance

which binds the lining cells of blood vessels not only

to their basement membrane but also to each other.

(See Coenzymes.)

Occurrence of Scurvy

0021Scurvy is now a rare condition but isolated cases can

still be seen in certain population groups. The at-risk

groups are often the elderly (not so much in North

America), food faddists, alcoholics, those living in

institutions, and patients with psychiatric disorders.

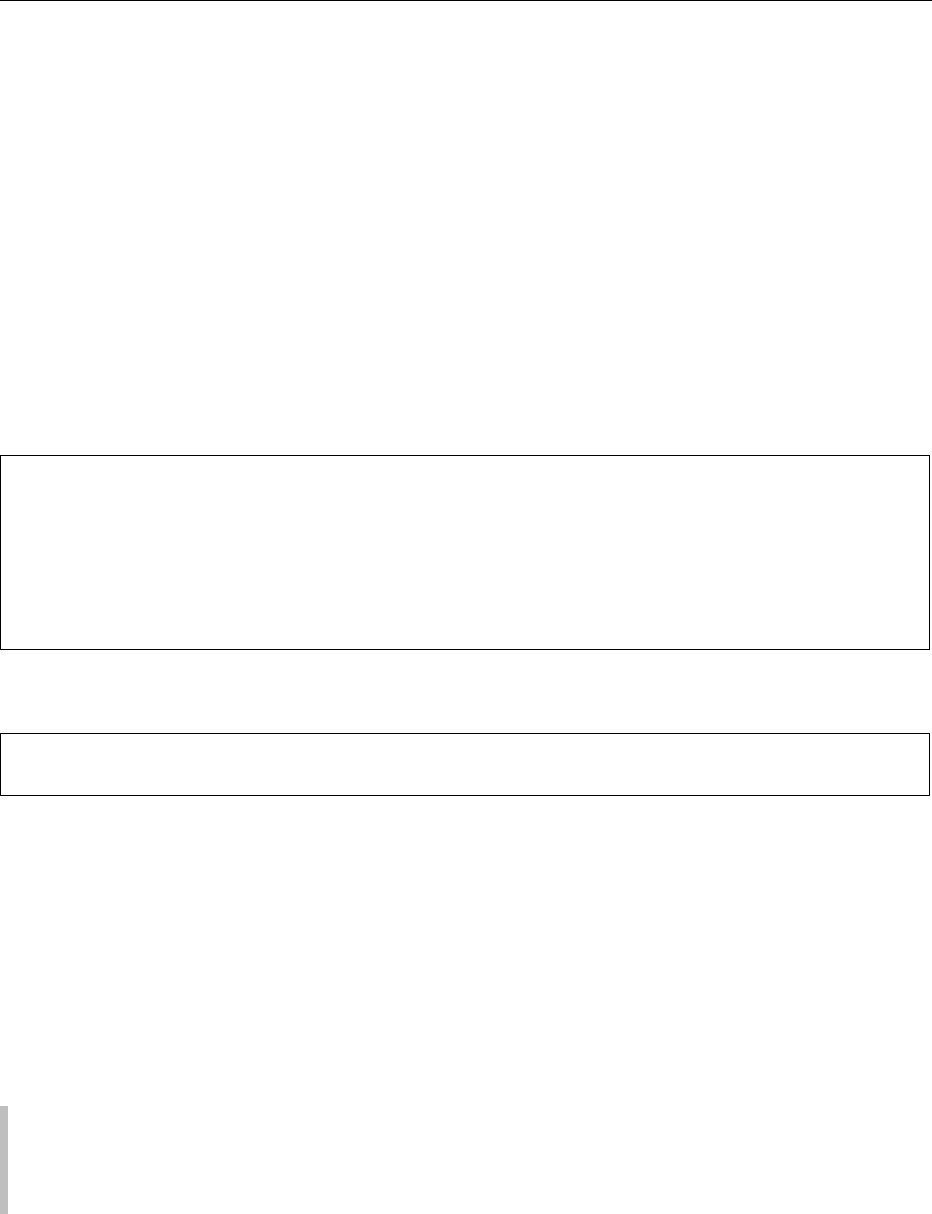

tbl0002 Table 2 The consequences of withdrawing vitamin C from the diet

Day

Plasma ascorbic acid Buffy coat ascorbic acid ^ inleukocytes (WC) Body poolof ascorbic acid

Clinical statemg l

1

mmol l

1

mg10

8

WC nmol 10

8

WC g nmol

0 8–15 45–85 21–57 119–323 0.6–1.5 3.4–8.5 Adults

20 3 17 10–38 57–216

40 1–3 6–17 2–10 11–57 0.3–0.6 1.7–3.4 Subclinical deficiency

60 <1 <6 <5 <28 0.3–0.6 1.7–3.4

80 <1 <6 <5 <28 0.3–0.6 1.7–3.4

100 <1 <6 <5 <28 0.3–0.6 1.7–3.4

120 <1 <6 <2 <11 <0.3 <1.7 Perifollicular hyperkeratosis

140 <1 <6 <2 <11 <0.3 <1.7

160 <1 <6 <2 <11 <0.3 <1.7 Petechiae and ecchymoses

of the skin and failure of

wounds to heal

180 <1 <6 <2 <11 <0.1–0.3 0.6–1.7 Gingival changes

200 <1 <6 <2 <11 <0.1 <0.6 Dyspnea, edema, and very

rapid progression

5110 SCURVY

Outbreaks of scurvy occur in poor nomadic popula-

tions in arid or semidesert districts when there is a

threat of famine or a long-standing drought. There is

also isolated evidence that long-term administration

of large doses of vitamin C could lead to adaptation

which might be responsible for developing scurvy,

following sudden cessation of the extra vitamin

intake. The conditioning effect is more pronounced

during intrauterine life than either following birth or

in adults. Overdosing with vitamin C during preg-

nancy may thus be contraindicated.

See also: Ascorbic Acid: Properties and Determination;

Physiology; Coenzymes

Further Reading

Basu TK (1985) The conditioning effect of large doses

of ascorbic acid in guinea pigs. Canadian Journal of

Physiology and Pharmacology 63: 427–430.

Basu TK and Schorah CJ (1982) Vitamin C in Health and

Disease. London: Routledge.

Carpenter KJ (1986) The History of Scurvy and Vitamin C.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Irwin MA (1976) A conspectus of research on vitamin C

requirements of man. Journal of Nutrition 106:

823–879.

Lind J (1976) A Treatise on the Scurvy. Republished (1953)

by Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

Vilter RW (1978) Nutrient deficiencies in man: vitamin C.

CRC Handbook Series (Nutrition and Food) 3: 91–103.

Seafood See Fish: Introduction; Catching and Handling; Fish as Food; Demersal Species of Temperate

Climates; Pelagic Species of Temperate Climates; Tuna and Tuna-like Fish of Tropical Climates; Pelagic Species of

Tropical Climates; Demersal Species of Tropical Climates; Important Elasmobranch Species; Processing;

Miscellaneous Fish Products; Spoilage of Seafood; Dietary Importance of Fish and Shellfish; Fish Farming; Fish

Meal; Shellfish: Characteristics of Crustacea; Commercially Important Crustacea; Characteristics of Molluscs;

Commercially Important Molluscs; Contamination and Spoilage of Molluscs and Crustaceans; Aquaculture of

Commercially Important Molluscs and Crustaceans; Marine Foods: Production and Uses of Marine Algae; Edible

Animals Found in the Sea; Marine Mammals as Meat Sources

Seaweed See Marine Foods: Production and Uses of Marine Algae; Edible Animals Found in the Sea; Marine

Mammals as Meat Sources

SELENIUM

Contents

Properties and Determination

Physiology

Properties and Determination

G F Combs Jr, Grand Forks Human Nutrition Research

Center, Grand Forks, ND, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 The chemical properties of the trace element selenium

are similar to those of sulfur; however, unlike sulfur,

which tends to be oxidized in biological systems,

selenium tends to undergo reduction in the tissues of

microbes, plants, and animals. Selenium is present in

most biological tissues at very low concentrations

where it is almost exclusively bound to proteins,

mostly as analogs of the sulfur-amino acids. Several

methods are available for the analysis of selenium;

the most commonly used ones are electrothermal

atomic absorption spectrophometry, and a chemical

procedure based on the formation of a fluorescent,

SELENIUM/Properties and Determination 5111

piazoselenol derivative. These methods are useful for

the quantitation of total selenium in tissues; however,

more sophisticated methods, such as those involving

high-performance liquid–liquid partition chromatog-

raphy linked with mass spectrometry, are required for

the chemical speciation of tissue selenium.

Chemical Forms of Selenium

0002 Selenium is in group IVa of the periodic table of

elements. This group includes the nonmetallic elem-

ents sulfur and oxygen in the periods above selenium

and the metallic elements tellurium and polonium in

the periods below. By period, selenium lies between

the group Va metal arsenic and the group VIIa non-

metal bromine. Thus, selenium is considered a metal-

loid, having both metallic and nonmetallic properties.

Its atomic properties are listed in Table 1.

0003 Elemental selenium shows allotropy; that is, it can

exist in either an amorphous state or in one of three

crystalline states. Amorphous selenium in a hard,

brittle glass at temperatures below 31

C, is vitreous

at 31–230

C, and is a free-flowing liquid above

230

C. The increased viscosity of amorphous selen-

ium at temperatures less than 230

C results from the

formation of polymeric chains. Crystalline selenium

can take several forms: flat, polygonal (often hex-

agonal) crystals called g-monoclinic or red selenium;

needle-like, prismatic crystals called g-monoclinic or

dark red selenium; or spiral polyatomic chains vari-

ously called metallic, gray or black selenium. Of these

forms, the most stable is the hexagonal, crystalline

form to which both monoclinic forms convert at tem-

peratures above 110

C and to which amorphous sel-

enium converts spontaneously at 70–120

C.

0004Elemental selenium can be reduced to the 2 (sel-

enide, Se

2

) oxidation state or oxidized to the þ4

(selenite, Se

þ4

)orþ6 (selenate, Se

þ6

) oxidation

states. Hydrogen selenide (H

2

Se) is a fairly strong

acid with a pK

a

of 3.8 in aqueous systems. It is a

colorless gas with an unpleasant odor. The gas is

highly toxic (the LC50 for 30 min exposure for guinea

pigs is 6 p.p.m.); however, Se

2

is also a pivotal

metabolite in animals and at least some microbes,

being the obligate precursor to selenocysteine at the

active centres of a number of physiologically im-

portant selenoenzymes. Hydrogen selenide can be

produced by heating elemental selenium (Se

0

) to tem-

peratures above 400

C, but it decomposes in air to

form the element and water. It is fairly soluble in

water (270 ml per 100 ml of water at 22.5

C). It

reacts directly with most metals to form insoluble

metal selenides. Organic selenides are ready electron

donors; thus, they are readily converted to higher

oxidation states.

0005In the þ4 oxidation state, selenium can exist as

selenium dioxide (SeO

2

), selenious acid (H

2

SeO

3

), or

selenite (SeO

3

2

). Selenium dioxide is formed by

burning elemental selenium in air, or by reacting it

with nitric acid. It is readily reduced to the elemental

state by ammonia, hydroxylamine, sulfur dioxide,

or a number of organic compounds. It is soluble in

water (38.4 g per 100 ml at 14

C) and forms seleni-

ous acid when dissolved in hot water. Selenious acid is

weakly dibasic (pK

a

2.6), and dissolved selenite salts

exist as biselenite ions in aqueous solutions at pH

3.5–9. In contrast to the organic selenides, selenites

readily accept electrons from their environments

and are, therefore, easily reduced. At low pH, selenite

is readily reduced to the elemental state by such

tbl0001 Table 1 Atomic properties of selenium

Atomic number 34

Atomic weight 78.96

Stable isotopes (natural abundance)

74

Se (0.87%),

76

Se (9.03%),

77

Se (7.58%),

78

Se (23.52%),

80

Se (49.82%),

82

Se (9.19%)

Radioisotopes (emission;

a

half-life)

70

Se (g

þ

, EC; 44 months);

71

Se (g

þ

, EC; 5 months),

72

Se (EC; 8.4 days),

73

Se (g

þ

, EC; 7.1 h),

75

Se (g-; 120.4 days),

77 m

Se (IT; 17.5 s),

79

Se (g-; 6.5 10

4

years),

81 m

Se (IT; 57 months),

81

Se (g-; 18.6 months),

83 m

Se (g-; 70 s),

83

Se (g-; 23 months),

84

Se (g-; 3.3 months),

85

Se

(g-; 39 s)

Electronic configuration Ar3d

10

4s

2

2p

4

Atomic radius 1.40 g

Covalent radius 1.16 g

Ionic radius 1.98 g

Common oxidation states 2, 0,

þ

4,

þ

6

M-M bond energy 44 kcal mol

1

M-H bond energy 67 kcal mol

1

Ionization potential 9.75 eV

Electron affinity 4.21 eV

Electronegativity 2.55 (Pauling’s scale)

a

emission codes: g

þ

, positron emission; g, negative beta emission; IT, isomeric transition; EC, orbital electron capture.

5112 SELENIUM/Properties and Determination

reducing agents as ascorbic acid and sulfur dioxide.

Selenites in soils are strongly bound by hydrous

oxides of iron, forming insoluble complexes at

moderate pH.

0006 In its highest oxidation state (þ6), selenium can

exist as selenic acid (H

2

SeO

4

) or selenate (SeO

4

2

)

salts. Selenic acid is a strong acid. It is formed by the

oxidation of selenious acid or elemental selenium

with strong oxidizing agents in the presence of

water. It is very soluble in water, as are most selenate

salts. Selenates tend to be rather inert and are very

resistant to reduction.

0007 Six stable isotopes of selenium exist in nature and

13 radioisotopes of the element can be produced by

neutron activation or radionuclear decay (Table 1).

The stable isotopes

74

Se,

76

Se, and

80

Se have been

employed in the study of the metabolism of selenite

and selenomethionine by humans; these can be de-

tected by mass spectrometry or neutron activation

analysis. The short-lived radioisotope

77m

Se (half-

life 17.5 s) has been used in the neutron activation

analysis of the element in biological materials. Due to

its emission of g-radiation and to its relatively long

half-life (120 days),

75

Se has proven widely employed

in biological experimentation and in medical diagnos-

tic work.

0008 Selenium is a semiconductor that exhibits photo-

conductivity; that is, excitation with electromagnetic

radiation can increase its conductivity. This property

has made selenium compounds useful in photovoltaic

cells and in xerography. As a result of the many

practical utilities conferred by this property, the

literature on the chemistry of inorganic and organic

selenium compounds is large.

0009 The selenium compounds of greatest relevance in

biology are listed in Table 2. It should be noted that,

whereas some dietary supplements and fortificants

of foods and livestock feeds include selenium com-

pounds of higher oxidation states (e.g., selenate

[Se

þ4

]), the major metabolites are in the reduced

(Se

2

) state.

Chemical Properties of Selenium

0010The chemical properties of selenium, like its physical

properties, are very similar to those of sulfur. The two

elements have similar outer valence shell electronic

configurations and similar atomic sizes in both

the covalent and ionic states. Their bond energies,

ionization potentials, and polarizabilities are virtually

the same. Despite these similarities, the chemistry of

selenium differs from that of sulfur in two important

respects which distinguish the elements in biological

systems: their oxyanions are not similarly reduced,

and their hydrides have different acid strengths. For

these reasons, selenium behaves very differently from

sulfur in biological systems.

0011In biological systems, selenium compounds tend to

be metabolized to more reduced states while sulfur

compounds tend to be metabolized to more oxidized

states. For example, quadrivalent selenium (Se

þ4

)in

selenite tends to undergo reduction to Se

2

, being

metabolized first to H

2

Se and, ultimately, being meth-

ylated to a variety of excretory forms. In contrast,

quadrivalent sulfur in sulfite tends to undergo oxida-

tion. This difference is demonstrated by the ability of

selenious acid to oxidize sulfurous acid: H

2

SeO

3

þ

2H

2

SO

3

!Se

0

þ2H

2

SO

4

þ H

2

O.

0012Although the oxyacids of selenium and sulfur have

comparable acid strengths (pK

a

2.6 versus pK

a

1.9,

respectively, for the quadrivalent species; pK

a

3 for

both of the hexivalent species), the hydride H

2

Se is

much more acidic than H

2

S (pK

a

3.8 versus 7.0,

respectively). This difference in acid strengths is

tbl0002 Table 2 Biologically important selenium compounds

Oxidation state Compound Biologicalrelevance

Se

2

H

2

Se Obligate metabolic precursor to selenoproteins

Methyl selenol, CH

3

SeH Excretory form (lung) shown to be anticarcinogenic

Dimethyl selenide, (CH

3

)

2

Se Excretory form (lung)

Trimethyl selenonium, (CH

3

)

3

Se

þ

Excretory form (kidney)

Selenomethionine Common food form; form in nonspecific Se-containing proteins (e.g., albumin);

metabolized to selenocysteine

Selenocysteine Common food form; form in selenoproteins; metabolized to H

2

Se

Se-methylselenomethionine Form found in some foods; metabolized to CH

3

SeH

Se-methylselenocysteine Form found in some foods; metabolized to CH

3

SeH

Selenobetaine Metabolic precursor of CH

3

SeH

Selenotaurine Form found in some foods

Se

0

Selenodiglutathione Reductive metabolite of selenite/selenate with anticarcinogenic activity

Se

þ4

Na

2

SeO

3

Commonly used feed supplemental form

Se

þ6

Na

2

SeO

4

Potential food/feed supplement form

SELENIUM/Properties and Determination 5113

reflected in the different dissociation behaviors of the

selenohydryl group (–SeH) of selenocysteine (pK

a

5.24) and the sulfhydryl group (–SH) of cysteine

(pK

a

8.25). This, while thiols such as cysteine are

mainly protonated at physiological pH, selenols

such as selenocysteine are predominantly dissociated

under the same conditions.

0013 Selenite (Se

þ4

) can readily react with nonprotein

thiols and with protein-sulfhydryl groups to undergo

reduction to Se

0

with the concomitant formation of

1,3-dithio-2-selane products of the form RS-Se-SR,

called ‘selenotrisulfides.’ In this reaction, 4RSH þ

H

2

SeO

3

!RS-Se-SR þ3H

2

O, four sulfhydryl sulfur

atoms (S

2

) are oxidized to the disulfide state (S

1

)

with the concomitant reduction of a single selenium

atom from the selenite state (Se

þ4

) to the zero

oxidation state. However, because the electrone-

gativities of selenium and sulfur are very similar, the

–2 charge may be distributed across the seleno-

trisulfide bridge, yielding an effective oxidation

number of –2/3 for each of its members. A similar

reaction can occur between selenite and free sulfhy-

dryl groups of proteins to yield selenodisulfide (RS-

SeH) and selenotrisulfide-type oxidation products

that, in some cases, can inhibit enzymatic activity.

Indeed, such reactions are thought to play a role in

selenium toxicity.

Analysis of Selenium

0014 The analytical challenge for determining selenium in

biological samples, i.e., plant and animal tissues, is to

detect quantitatively the element over at least three

orders of magnitude of concentration. The nutritional

assessment of selenium status calls for analytical pro-

cedures capable of measuring plasma/serum selenium

levels in individuals who may be adequately nour-

ished (> 80 p.p.b. selenium), marginally nourished

(40–80 p.p.b.), frankly deficient (< 40 p.p.b.), or po-

tentially intoxicated (> 1000 p.p.b.). The analysis of

selenium in foods and feedstuffs calls for methods

capable of measuring the element in the range of

20–500 p.p.b., while the detection of selenium in

nonprotein-bound fractions of animal/human tissues

calls for detection capability of 1–5 p.p.b.

0015 Several procedures are available for the quantita-

tive determination of selenium; however, some that

have industrial utility do not lend themselves to bio-

logical applications due to their relatively low sensi-

tivities. Such methods include both gravimetric (e.g.,

after reduction and quantitative precipitation with

acid or electrolytic deposition with copper) and col-

orimetric ones (e.g., titration with oxidizing agents

after reduction with thiocyanate; measurement of

selenium hydrosols after reduction by hydrazine,

stannous chloride, or ascorbic acid; measurement of

azo-compounds formed by the reaction of aromatic

amines with diazonium salts produced by the oxida-

tion of organic compounds by selenite; measurement

of complexes of Se

2

with phenyl-substituted thicar-

bazides or semicarbazide after reduction of selenium).

The limit of detection of none of these methods is less

than 0.5 p.p.m. and, for the gravimetric methods,

they can be several parts per million. None of these

procedures is free of interferences that can give false-

positive results; other elements can coprecipitate with

selenium to affect the results of gravimetric methods,

and other oxidizing agents that can affect the colori-

metric methods.

0016Other methods have been found to be more useful

for the determination of selenium in plant and animal

tissues. These include: (1) fluorimetric measurement

of selenium, after nitric-perchloric acid digestion and

conversion to Se

þ4

, using diaminonaphthalene (DAN)

to form benzopiazselenol; (2) atomic absorption spec-

trophotometry; (3) instrumental neutron activation

analysis; (4) mass spectrometry; (5) atomic fluores-

cence spectroscopy; (6) inductively coupled plasma

emission spectroscopy; and (7) proton-induced X-

ray emission spectrometry. Each of these approaches

can yield sensitivity less than 5 p.p.b. Of these,

the methods most widely employed in biomedical

applications have been the DAN-fluorimetric and

electrothermal atomic absorption methods.

0017The chemical determination of selenium by the

DAN-fluorimetric method is of lower cost with com-

parable sensitivity (2–5 p.p.b.) compared to most

other methods. This method necessitates the quanti-

tative conversion of the selenium in the sample to

Se

þ4

. Because most, if not all, selenium in biological

tissues occurs as Se

2

compounds, this is achieved

using nitric-perchloric acid digestion to oxidize or-

ganic matter and form Se

þ6

. This is followed by

treating the sample with hydrochloric acid to reduce

any Se

þ6

that may be present to the þ4 oxidation

state. Se

þ4

is reacted with DAN, yielding benzopiaz-

selenol which is extracted into cyclohexane and meas-

ured fluorimetrically (excitation 390 nm; emission

520 nm). The DAN-fluorimetric method has two

points of vulnerability: effect that impairs the conver-

sion of selenium to Se

þ4

, and factors that produce

fluorescence interference. One potential source of

the first type of error is the loss of volatile H

2

Se

formed in the transition, particularly in the presence

of large amounts of organic matter such that sample

charring can occur (e.g., fatty materials such as egg

yolk or adipose tissue). Because H

2

Se is volatilized

from acid solutions by reducing agents, this loss can

be avoided by maintaining strongly oxidizing condi-

tions during digestion and by using low heat such that

5114 SELENIUM/Properties and Determination

the oxidation of Se

þ4

to Se

þ6

proceeds relatively

slowly (this can be achieved by gradually raising the

temperature of the perchloric acid solution to

210

C). When the nitric-perchloric acid digestion is

controlled and carefully attended, it produces satis-

factory conversion to Se

þ4

, even of such forms as

trimethylselenonium which is resistant to oxidation

by nitric acid alone. The second type of problem

involves fluorescence interference caused by degrad-

ation products of DAN. This can be avoided by puri-

fying DAN prior to use either by recrystallization

from water in the presence of sodium sulfite and

activated charcoal, or by hexane extraction after

hydrochloride stabilization.

0018 Although conventional atomic absorption spectro-

photometry (AAS) does not yield satisfactory sensi-

tivity for most biological applications, two variant

methods do so. The best results are obtained using

electrothermal AAS which avoids the problems asso-

ciated with wet digestions by employing high-

temperature oxidation and antomization in a graphite

furnace. This reduces interferences due to nonspecific

absorption of organic compounds and nonselenium

salts, but introduces the problem of selenium volatil-

ity under such conditions and can also be prone to

‘matrix’ effects, particularly due to phosphate. These

sources of interference can be effectively reduced by

using a palladium-based matrix modifier to reduce

the volatility and, thus, permit the vaporization of

nonselenium compounds at lower furnace tempera-

tures than those used to vaporize and quantitate sel-

enium. Also effective is background correction by the

Zeeman effect, in which a magnetic field is used to

split the resonance line into its Zeeman components,

converting a single beam into a double one, the wings

of which can be monitored with polarizers to assess

the background while the central portion is moni-

tored to assess the analyte. In practice, electrothermal

AAS with the use of automatic Zeeman-effect back-

ground correction can achieve a sensitivity of 2 p.p.b.

A less sensitive AAS technique involves the pretreat-

ment of the sample with sodium borohydride and

acid to convert selenium to H

2

Se. This method re-

quires selenium to be in solution as Se

þ4

, which can

be achieved by nitric-perchloric acid digestion of the

sample, after which the hydride generation step can

be automated. This approach yields a limit of detec-

tion of only 50–100 p.p.b. and is subject to interfer-

ences due to other elements that can also form

hydrides, particularly copper.

0019 Investigators with access to research atomic react-

ors have found instrumental neutron activation an-

alysis of selenium to be very useful, as it offers the

advantages of applicability to small samples, ease of

sample preparation, and nondestruction of sample.

The greatest sensitivity, about 20 p.p.b., by this

method is obtained by measuring

75

Se; however, the

use of that radioisotope requires relatively lengthy

periods of irradiation (100 h), postirradiation holding

(60 days) and counting (2 h), making it relatively

expensive. Greater economy and increased sample

throughput are achieved through the use of the

short-lived

77 m

Se which can be produced by only 5 s

of irradiation, and counted (25 s) after only 15 s

of decay using an automated system. Nevertheless,

this fast method is limited by its relatively low sensi-

tivity, rendering it unsuitable for accurate quan-

titation of such low amounts of selenium as are

found in tissues of animals chronically deficient in

the element.

0020Selenium can be measured by mass spectrometry,

which method offers the distinct advantage of being

able to distinguish between the major stable isotopes

of the element. There is, therefore, great interest in

developing mass spectrometric techniques for use in

metabolic studies in which

74

Se,

76

Se, or

82

Se are used

as tracers. Mass spectrometric procedures have been

developed for determining selenium in biological

samples by isotope dilution. These involve the analy-

sis of the naturally abundant

80

Se in addition to

82

Se

which is used as an internal standard. Samples spiked

with known amounts of the internal standard are

treated by nitric-perchloric acid digestion to convert

all of the selenium in the sample to Se

þ4

. The latter

can be chelated using o-nitrophenylenediamine, ex-

tracted into an organic solvent, and subjected to gas–

liquid partition chromatography–mass spectrometry

to determine the ratios of

82

Se to

80

Se, comparing that

ratio to the ratio of the one naturally occurring in the

sample. Mass spectrometry can yield limits of detec-

tion for selenium as low as 1 p.p.b. The technique

known as inductively coupled plasma mass spect-

rometry (ICP-MS) involves coupling using mass

spectrometry inline after ionizing the sample in a

high-temperature plasma.

0021Selenium can be measured by emission spectropho-

tometry using either a flame or high-temperature

plasma to atomize selenium. A very sensitive atomic

flame fluorescence spectrophotometric method uses

automated hydride generation of a predigested

sample. This method has not been widely used, but

offers very good specificity, in as much as only a few

elements can form volatile hydrides and as the fluor-

escence emission wavelength can be measured select-

ively. The method offers impressive sensitivity with

limits of detection on the order of 2–5 p.p.t.; the

sample dilution usually required for hydride gener-

ation reduces the working limit of detection to the

20–50 p.p.t. range, which is still superior to other

methods. Selenium can be measured by inductively

SELENIUM/Properties and Determination 5115

coupled plasma emission spectrometry, which offers

the advantage of the simultaneous determination

of other elements. This method can yield limits of

detection of about 1 p.p.b., but is limited by spectral

interferences of the dimeric argon formed in the

plasma.

0022 The measurement of selenium by proton-induced

X-ray emission (PIXE) spectroscopy offers the poten-

tial advantage of simultaneous analysis of other elem-

ents. This method involves proton bombardment of

target atoms to cause loss of the latters’ inner-shell

electrons which are consequently replaced by elec-

trons from the outer shell. The X-rays emitted during

that transition are characteristic of the energy differ-

ences between the respective electron shells and are,

therefore, identifiable and quantifiable. The sensitiv-

ity of the PIXE procedure for the determination of

selenium is about 10 p.p.b., making it useful for some

biological purposes but not sufficiently sensitive for

the accurate determination of very low tissue levels of

the element.

Chemical Speciation of Selenium

0023 Most selenium naturally present in biological mater-

ials appears to be in the reduced (selenide) state, Se

2

.

There is, however, little information available con-

cerning the various chemical forms in which that

Se

2

occurs in plant and animal tissues. Studies have

shown that the selenium in wheat and corn grown on

seleniferous soils is predominantly protein-bound; in

wheat half or more occurs as the selenium analog of

methionine, selenomethionine. Because plants cannot

synthesize the cysteine analog selenocysteine, it is

generally thought that selenomethionine is the pre-

dominant form of the element in plant tissues in

which it acts as a methionine mimic in general protein

metabolism. This is not the case for animals and at

least some microorganisms, which can biosynthesize

selenocysteine from H

2

Se. In fact, it is as selenocys-

teine in specific selenoenzymes that selenium serves

its nutritionally essential metabolic functions. There-

fore, the tissues of selenium-fed animals and humans

typically contain both selenocysteine from the biosyn-

thesis of selenoproteins as well as selenomethionine

derived from the diet and used nonspecifically in

general protein synthesis. In addition to these two

main forms, it is clear that plant tissues can contain

smaller amounts of certain derivatives, including

Se-methylselenomethionine and Se-methylselenocys-

teine, and that animals produce metabolically both

H

2

Se as well as a number of methylated excre-

tory metabolites thereof (methylselenol, dimethylse-

lenide, and trimethylselenonium); however, there are

virtually no data currently available concerning the

amounts of these metabolites in animal or human

tissues.

0024The chemical determination of selenium species

is the next frontier in the analytical chemistry of

selenium. Recent efforts in this area have involved

the use of gas–liquid partition chromatographic sep-

aration techniques coupled with atomic plasma emis-

sion detection methods for the simultaneous

detection and quantitation of selenoamino acids; of

ethylation derivatization to separate volatile organo-

selenium compounds; and of ion-pair, reverse-phase,

high-performance liquid–liquid partition chromatog-

raphy couple to ICP-MS for the determination of

selenoamino acids, selenoxides, and other selenium

derivatives. Future efforts in this field are likely to

employ molecular mass spectrometry.

See also: Chromatography: High-performance Liquid

Chromatography; Mass Spectrometry: Principles and

Instrumentation; Applications

Further Reading

Alfthan G and Kumpalainen J (1982) Determination of

selenium in small volumes of blood plasma and serum

by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry.

Analytical Chemica Acta 140: 221.

Kotrebai M, Birringer M, Tyson JF, Block E and Uden PC

(2000) Selenium speciation in enriched and natural

samples by HPLC-ICP-MS and HPLC-ESI-MS with per-

fluorinated carboxylic acid ion-pairing agents. Analyst

125: 71.

Kumpalainen J (1990) Summary of new analytical tech-

niques and general discussion. In: Tomita H (ed.) Trace

Elements in Clinical Medicine, p. 451. New York:

Springer.

Kumpalainen J, Raittila AM, Lehto J and Koivisoinen P

(1983) Electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometric

determination of selenium in foods and diets. Journal of

the Association of Official Analytical Chemists 66:

1129.

Olson OE, Palmer IS and Cary EE (1975) Modification of

the official fluorimetric method for selenium in plants.

Journal of the Association of Official Analytical Chem-

ists 58: 117.

Reilly C (1996) Selenium in Food and Health. New York:

Blackie Academic & Professional.

Spate VL, Mason MM, Reams CL et al. (1994) Determin-

ation of total, and bound Se in sera by INNA. Journal of

Radiological and Nuclear Chemistry 179: 315.

Uden PC, Bird SM, Kotrebai M et al. (1998) Analytical

selenoamino acid studies by chromatography with inter-

faced atomic mass spectrometry and atomic emission

spectral detection. Fresenius’ Journal of Analytical

Chemistry 362: 447.

5116 SELENIUM/Properties and Determination