Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

explained simply as being due to the reduction in the

concentration of free bile acid, because bile acids

assist lipid absorption. Low concentrations of free

bile acids would also impair the efficiency of lipid

absorption and presumably affect the absorption of

fat soluble vitamins. Thus, there may also be a signifi-

cant metabolic effect within the animal as well as in

the digestive tract.

Effects on Growth

0018 When lucerne saponin was added at high levels to the

diets of monogastric animals, reduced feed efficiency

and growth rates were observed. It is clear that

species differ considerably in their responses to diet-

ary saponin, e.g., poultry are more sensitive than rats.

In contrast, soya bean saponins had little effect on the

growth rate of experimental animals. Some saponins

increase the permeability of the small intestinal muco-

sal cells, thereby inhibiting the active transport of

some nutrients, but at the same time, they facilitate

the uptake of materials to which the gut would nor-

mally be impermeable.

0019 The biochemical mechanism that accounts for the

growth-depressing effects has not been fully identi-

fied. In at least one experiment, the addition of 1%

cholesterol to the diets of chicks completely overcame

growth depression produced by 0.3% saponin.

0020 It is possible that, in addition to their effects on

lipid absorption, saponins also affect chymotrypsin

and trypsin activity, which would affect the absorp-

tion of protein. (See Protein: Digestion and Absorp-

tion of Protein and Nitrogen Balance.)

0021 In addition to observing reduced intestinal uptake

of cholesterol in rat intestinal perfusates on the

addition of soy saponin extracts, some workers have

also observed a significant reduction in cholate and

glucose uptakes. It was observed that the saponins

could be washed out of the intestinal lumen, suggest-

ing that inhibition, at least in the short term, was not

caused by modification of, or damage to, the intes-

tinal mucosa.

Metabolism of Saponins

0022 Toxicity studies indicate that only very low levels of

saponin absorption occur. Saponins are between 10

and 1000 times more toxic when administered intra-

venously than when given orally. Destruction of sap-

onins in the digestive tract of both ruminants and

monogastric animals has been observed. Saponins

are degraded by rumen bacteria and by microflora

found in the cecum of rats, mice, and chicks. Since

saponin in the cecum is past the major sites of absorp-

tion, the release of sapogenins and sugars is con-

sidered to be insignificant.

Conclusions

0023The substantial evidence that saponins from a

number of plant species can reduce plasma choles-

terol levels in man is likely to encourage further inter-

est in these plant foods. It is generally recognized that

the overall nutritional value of many Western type

diets would be considered improved if more legumes

or legume-based products were consumed regularly.

The acceptance of more legumes in Western type diets

is limited by undesirable taste characteristics, some of

which may be due to the higher levels of saponin

found in many legume seeds.

0024There is little doubt that saponins can be incorpor-

ated into human diets at levels that can give a benefi-

cial effect and would not entail a risk of acute

toxicity. The fact that saponins can increase the

permeability of intestinal mucosa raises the possibil-

ity of interesting nutritional and pharmacological

uses.

See also: Beans; Bile; Cereals: Dietary Importance;

Cholesterol: Role of Cholesterol in Heart Disease;

Chromatography: Principles; Fats: Digestion,

Absorption, and Transport; Legumes: Legumes in the

Diet; Protein: Digestion and Absorption of Protein and

Nitrogen Balance; Pulses; Sensory Evaluation: Taste

Soy (Soya) Beans: Properties and Analysis

Further Reading

Anderson JO (1957) Effect of alfalfa saponin on the per-

formance of chicks and laying hens. Poultry Science 36:

873–876.

Birk Y (1969) Saponins. In: Liener IE (ed.) Toxic Constitu-

ents of Plant Food Stuffs, pp. 169–210. New York:

Academic Press.

Birk Y, Bondi A, Gestetner B and Ishaaya I (1963) A

thermostable haemolytic factor in soybeans. Nature

197: 1089–1090.

Calvert GD, Bligh L, Illman RJ, Topping DL and Potter JD

(1981) A trial of the effects of soya bean flour and soya-

bean saponins on plasma lipids, faecal bile acids and

neutral sterols in hypercholesterolaemic men. British

Journal of Nutrition 45: 277–281.

Cheeke PR (1971) Nutritional and physiological implica-

tions of saponins: a review. Canadian Journal of Animal

Science 51: 621–632.

Fenwick DE and Oakenfull D (1983) Saponin content of

food plants and some prepared foods. Journal of the

Science of Food and Agriculture 34: 186–191.

Gestetner B, Birk Y and Tencer Y (1968) Soybean saponins.

Fate of ingested soybean saponins and the physiological

aspects of their hemolytic activity. Journal of Agricul-

tural and Food Chemistry 16: 1031–1035.

Heaton KW (1972) Bile Salts in Health and Disease. Edin-

burgh: Churchill Livingstone.

SAPONINS 5097

Johnson IT, Gee JM, Price K, Curl C and Fenwick GR

(1986) Influence of saponins on gut permeability and

active nutrient transport in vitro. Journal of Nutrition

116: 2270–2277.

Malinow MR, McLaughlin P, Kohler GO and Livingston

AL (1977) Prevention of elevated cholesterolemia in

monkeys by alfalfa saponins. Steroids 29: 105–110.

Malinow MR, Connor WE, McLaughlin P et al. (1981)

Cholesterol and bile acid balance in Macaca fascicularis

– effects of alfalfa saponins. Journal of Clinical Investi-

gation 67: 156–162.

Oleszek WA (2002) Chromatographic determination of

plant saponins. Journal of Chromatography A 967(1):

147–162.

Pathirana C, Gibney MJ and Taylor TG (1980) Effects of

soy protein and saponins on serum, and liver cholesterol

in rats. Atherosclerosis 36: 595–599.

Pistelli L, Bertoli A, Lepori E, Morelli I and Panizzi L (2002)

Antimicrobial and antifungal activity of crude extracts

and isolated saponins from Astragalus verrucosus.

Fitoterapia 73(4): 336.

Potter JD, Illman RJ, Calvert GD, Oakenfull DG and Tap-

ping DL (1980) Soya saponins, plasma lipids, lipopro-

tein and fecal bile acids. Nutrition Reports International

22: 521–528.

Price KR, Curl CL and Fenwick GR (1986) The saponin

content and sapogenol composition of the seed of 13

varieties of legume. Journal of the Science of Food and

Agriculture 37: 1185–1191.

Sidhu GS and Oakenfull DG (1986) A mechanism for

hypocholesterolaemic activity of saponins. British

Journal of Nutrition 55: 643–649.

Sirtori CR, Agradi E, Conti F, Mantero O and Gatti E

(1977) Soybean protein diet in the treatment of type II

hypercholesterolaemia. Lancet I: 275–277.

Yayla Y, Alankus-Caliskan O, Anil H, Bates R, Stessman C

and Kane V (2002) Saponins from Styrax officinalis.

Fitoterapia 73(4): 320.

Sardines See Fish: Introduction; Catching and Handling; Fish as Food; Demersal Species of Temperate

Climates; Pelagic Species of Temperate Climates; Tuna and Tuna-like Fish of Tropical Climates; Demersal Species

of Tropical Climates; Pelagic Species of Tropical Climates; Important Elasmobranch Species; Processing;

Miscellaneous Fish Products; Spoilage of Seafood; Dietary Importance of Fish and Shellfish; Fish Farming; Fish

Meal

SATIETY AND APPETITE

Contents

Food, Nutrition, and Appetite

The Role of Satiety in Nutrition

Food, Nutrition, and Appetite

D A Booth, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston,

Birmingham, UK

This article is reproduced from Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Copyright 1993, Academic Press.

Introduction

0001 Appetite for food and drink is the momentary dispos-

ition of an individual to seek and ingest edible or

potable materials. The concept of having an appetite

for food and drink has been widely misunderstood.

Appetite has often been assumed to be a subjective

phenomenon, private to a person’s consciousness.

The view has been held that appetite can be measured

by a rating procedure, such as marking a visual

analog scale (a line labeled at each end, e.g., with

the phrases, ‘extremely hungry’ and ‘not at all

hungry’), or magnitude estimation (assigning

numbers to the strengths of a named aspect of

awareness).

0002A measure of appetite, whether based on ratings,

behavioral patterns, or intakes, is an objective

5098 SATIETY AND APPETITE /Food, Nutrition, and Appetite

estimate of the strength of influence of specified cur-

rent determinants on the disposition to seek and con-

sume food. Appetite is a publicly observable

relationship between the tendency to ingest and the

sensed food composition, the culturally interpreted

context, and the bodily state of the eater or drinker.

0003 Appetite has also been restricted to facilitatory

influences that come from food, or at least from

outside the skin. In such terminology, facilitation

from under the skin is often called hunger (and only

the inhibition of eating from truly physiological

sources is called satiety). Alternatively, appetite is in

the mind, and hunger in the body.

0004 However, appetite is not one sort of influence on

eating behavior – external, mental, or other. Ingestive

appetite is the causal structure by which all influences

are momentarily affecting eating and drinking. It is

sometimes necessary to distinguish appetite for food

(hunger) from appetite for drink (thirst). The subject-

ive experience of hunger can be referred to external

sources, as in a food craving or the desire to eat at the

usual time, not just to bodily sensations such as the

epigastric pang.

Aspects of Appetite

0005 The immediate causes of eating and drinking might

be crudely divided into three categories, which can

be dubbed sensory, somatic, and social. This subdiv-

ision is not entirely coherent, however, because appe-

tite is an integral whole. Not only do sensed food

factors interact among themselves in the consumer’s

mind but also the sensory configuration interacts with

physiological factors and economic, cultural, and

interpersonal factors, in determining a momentary

decision to accept an item of food or drink.

0006 It is therefore scientifically and practically unwise

to study one factor by itself, especially out of the

normal context of eating (or of food purchase or

preparation). Moreover, it cannot be assumed that

sensory, social, and somatic groups of factors inde-

pendently add into the disposition to eat or purchase

a food. Thus neither theory nor application is sound if

based solely on economics or physiological or sensory

research. (See Food Acceptability: Affective Methods.)

Sensory Aspects of Appetite

0007 The influences on eating or drinking that arise imme-

diately from the sensing of the food or drink have

traditionally been called palatability. However, incor-

rect assumptions are made in many uses of this term;

one such assumption is that palatability is an invari-

ant property of the food or drink itself. Palatability is

not inherent to the food; it is an effect of the food on

the eater. This effect can vary, not just between

people, but within a person in different contexts

of eating.

0008The ordinary person regards foods as having con-

stant palatabilities, even if varying from person to

person. It is natural to deny that one stopped eating

because the food became less palatable; cessation of

eating is generally attributed to feeling full or to

having had an appropriate amount to eat.

0009Many scientific investigations and theories have

also treated palatability as a constant sensory effect.

In physiological psychology, for example, the stand-

ard account of the control of meal size is that accu-

mulating satiety subtracts from constant palatability

until insufficient facilitation of eating exists to con-

tinue the meal. It is more likely, however, that the

sensory facilitation differs between the contexts of

starting and ending a meal. When the sensory facili-

tation of eating is actually measured during or from

before to after meals, it typically decreases to a min-

imum at the end of eating and for some while after-

wards. Moreover, at the anecdotal level, a savoury

course is not expected to be as palatable after a sweet

dessert as it would be before the dessert.

0010Measurement of sensory preferences Any measure

of the sensory aspect of appetite must compare the

responses to two or more foodstuffs differing in

known sensed characteristics, unconfounded by any

other differences that might affect the responses.

Whether the responses are concrete (such as selection

among the foods) or symbolic (such as numerical or

line rating of liking, pleasantness, or likelihood of

choice), and whether the food samples are presented

simultaneously (e.g., triadic test) or successively (i.e.,

monadically), the relative acceptances give an esti-

mate of the sensory preference of that assessor in the

context of testing.

0011Attention must be given to the basic psychological

mechanisms operative in sensory effects on food

choice. The most preferred version of a food for a

consumer in a given context is always a particular

physicochemical configuration of its sensed charac-

teristics. In fact, the individual’s ideal point is a more

precise sensory level than a descriptive verbal anchor

(such as ‘extremely strong’) and is often no worse

than a familiar physical standard. Taken with a

second sensory anchor, such as apparent absence of

the characteristic or perhaps a presence so weak (or

so strong) as to be unacceptable, the ideal point de-

fines a sensory scale as objectively and precisely as

any purely descriptive rating. The crucial require-

ments are that each tested sensory level is described

by the assessor or identified by the investigator as

above or below the ideal level and that the prefer-

ence-anchored responses are scored according to

SATIETY AND APPETITE /Food, Nutrition, and Appetite 5099

sensory level, not for degree of preference. (See

Sensory Evaluation: Sensory Characteristics of

Human Foods; Food Acceptability and Sensory

Evaluation.)

0012 The raw sensory preference scores and the slopes of

plots of these scores against physical levels are as

meaningful as conventional descriptive scores and

slopes (or psychophysical power function exponents).

They can be averaged across a panel and tested stat-

istically for differences between samples. This

amounts merely to data analysis, however; it is not

scientific measurement of the strength of influences

on food perception or appetite. The most direct step

towards efficient design of palatable foods, rather, is

to use the effect of levels on score to measure causal

strength: the sensitivity of each assessor’s preference

to a physically measured factor should be calculated

from the slope and residual variance of a linear plot of

responses against sensory levels, using general psy-

chological theory of the mechanisms by which differ-

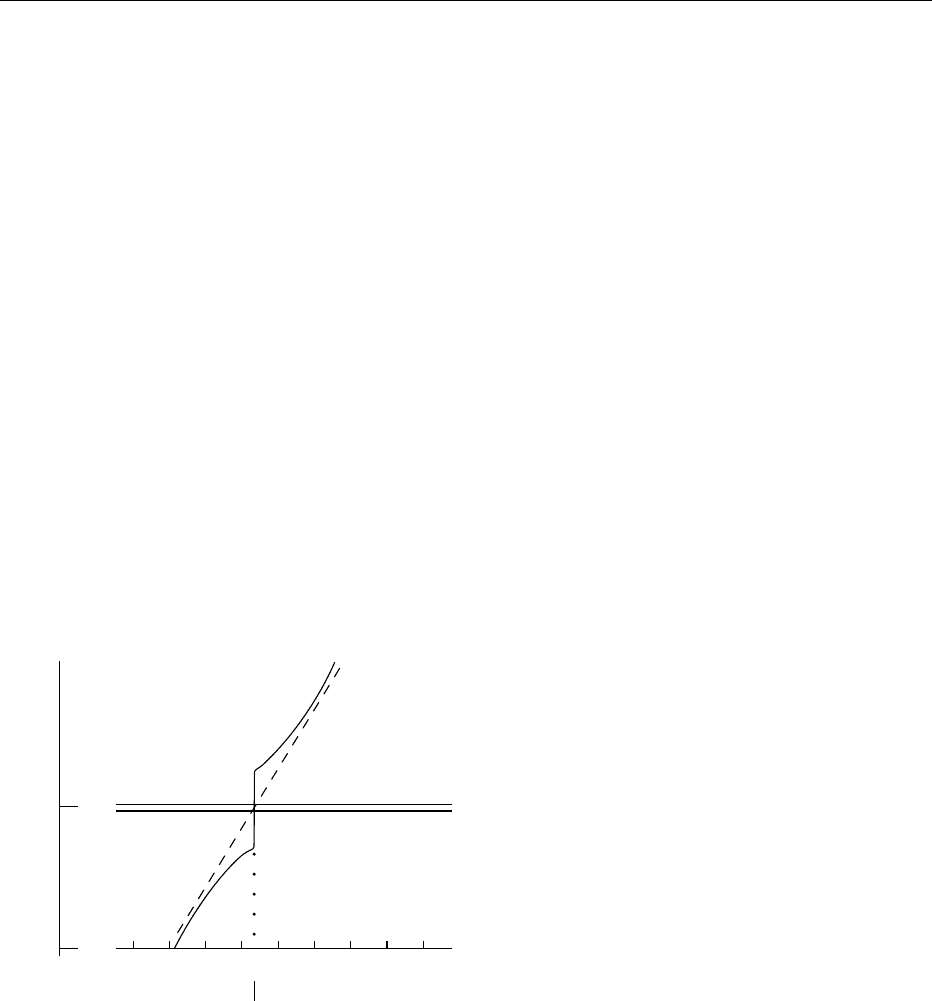

ent responses are given to different signals (Figure 1).

(See Sensory Evaluation: Sensory Rating and Scoring

Methods.)

0013A great advantage of this approach is that sensitiv-

ity of perception or preference to each investigated

factor can be estimated when the other foods, or

the social and somatic contexts of the test, depart

moderately from the combination in which the tested

food is normally eaten or purchased. If tolerably

low and high levels of a factor are well and equally

represented among the responses, the ideal level and

the sensitivity can be interpolated with fair accuracy.

Moderate inappropriateness in the context of testing

creates a Euclidean discontinuity which is virtually

confined to the midrange of the theoretical linear

function (Figure 1).

0014The sensitivities of a preference response to differ-

ent factors can be used to identify how those factors

interact in the individual’s mind in the test situation,

potentially enabling understanding of how a food

works in dietary habits. Preference characteristics

can also be aggregated across a panel of representa-

tive consumers. This could be used to give a physic-

ally and behaviorally objective market-response

surface from which one or more popular products

could be designed.

Somatic Aspects of Appetite

0015Somatic influences on appetite include physiological

signals of hunger, thirst, and satiety from the digestive

tract or from tissues such as the liver or the brain

itself, as well as these and other postingestional

effects of foods that induce sensory preference or

aversion.

0016As already indicated, even a physiological signal of

hunger or satiety (such as gastric motility or disten-

sion) is likely to operate through particular sensory

configurations when the eating situation is familiar.

There is evidence that appetite from an empty stom-

ach is stronger for an entre

´

e than a dessert, and vice

versa for a partly filled stomach. Similarly, we should

expect conventions about foods that are appropriate

to particular times of day (such as breakfast) to affect

hunger from an empty upper intestine or the satisfac-

tion of appetite arising from stimulation of the in-

testinal wall or hepatic metabolism, although such

hypotheses remain to be tested physiologically. Inves-

tigation of behavior at ordinary meals is necessary to

elucidate the normal operation of somatic factors in

appetite. Evidence for particular physiological signals

has been obtained with unusual foods at imposed

times but that leaves open the role of a signal in

everyday eating and drinking.

0017Those physiological factors which alter food pref-

erences by associative conditioning or other forms of

learning are interacting with sensory factors. It must

be noted that they are interacting quite differently

X Just

right

No X

at all

Equally discriminable levels of X

Ideal

p

oint

fig0001 Figure 1 Effect of equally discriminable differences in level of a

described sensory or other influence on appetite on the strength

of that factor, rated from too weak to be recognized to ideal

strength, in a context where other factors are at inappropriate

levels. The response line is in the Euclidean distance of the factor

level from ideal, i.e., the square root of the sum of the square of

the difference of a test sample from the influence’s ideal level and

a constant that represents the square of the size of the contextual

defect; its discontinuity around the ideal point is the truncation of

the preference peak by this defect. Reproduced from Satiety and

Appetite, Food, Nutrition, and Appetite, Encyclopaedia of Food

Science, Food Technology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK

and Sadler MJ (eds), 1993, Academic Press.

5100 SATIETY AND APPETITE /Food, Nutrition, and Appetite

from the contemporaneous mixing of factors con-

sidered elsewhere in this article. Indeed, a preference

acquired by the association of certain sensory charac-

teristics with a physiological consequence might be

unaffected if the conditioning physiological event

recurs when the conditioned food stimuli are also

present. In psychology, this distinction in mechanisms

is referred to as the difference between reinforcement

and motivation, or between learning and perform-

ance. The distinction is crucial to the understanding

of learned behavior such as normal appetite.

0018 The same metabolic signals that inhibit appetite

may also induce preferences for food flavors and

textures presented shortly beforehand. This is the

main basis for the desire for familiar foods, ranging

from the appetite for a staple food, such as potatoes

or bread, to the craving for an indulgence item such as

chocolate. Association with these reinforcers enables

bodily states (such as a partly full stomach) and

external situations (such as lunchtime, or a party

atmosphere) to acquire a learned power to motivate

or de-motivate eating or drinking.

0019 The temporal pattern of appetite suppression

following the consumption of a particular type of

menu also appears to be learnt. Such expectations

of satisfaction may be at least as important as physio-

logical signals in the sensation of fullness and in the

rise of appetite before the next meal.

0020 Additional physiologically mediated psychological

effects of foods are suspected to condition sensory

preferences or to create functional expectations of

sensorily identified foodstuffs or beverages, although

conclusive evidence is lacking. These appetite-

reinforcing somatic factors include the stimulant

action of caffeine and the sedating action of a heavy

meal or of alcohol. However, cultural stereotypes and

personal experience can create stimulant, soothing, or

cheering effects from consumption of a drink or food,

without any specific physiological basis.

0021 A somatic factor in appetite can only be identified

if the study disconfounds variations in the physio-

logical effect from variations in both social and sens-

ory effects. Neglect of this point has led to ill-founded

claims of measuring physiologically specific aspects

of appetite, such as carbohydrate craving, protein

selection, protein- and fiber-induced postingestional

satiety signals, and gastric distension satiety. The

technical difficulties are daunting, but there is no

gain in knowledge from neglecting these variations.

0022 All relevant sensory and social factors, as well as

somatic factors, must be specifically manipulated

and/or measured as perceived by the individual, and

shown to be uncorrelated with the physiological

effect(s) of interest. Only then can the sensitivity of

appetite to that somatic factor in that context be

estimated, or indeed even a qualitative effect of the

factor be established.

Social Aspects of Appetite

0023Interpersonal, cultural, and economic factors in ap-

petite appear to influence food choices by modulating

the effects of sensory factors. It may be feasible to

investigate a range of foods or drinks for general

effects of factors such as price, declared sweetener

type, or use by children, on appetite at the point of

purchase, serving, or ingestion. However, effects may

be specific to a food.

0024Social influences on appetite are often present in a

symbolic form, e.g., the category of eating occasion

or type of company at the meal, a brand logo, an

advertising picture, compositional information, or

the price label attached to a food item. Social factors

do not differ from rated sensations generated by

foods or in the body: descriptive scores that relate to

physical factors can be used to model sensory and

somatic aspects of appetite; hence the procedure for

scaling a social factor and estimating its strength of

influence on appetite is the same in principle as that

for other factors.

Psychology, Society, and Nature

0025Appetite is a psychological phenomenon, an aspect of

the mental processes organizing an individual’s be-

havior. Hence the cognitive approach to food con-

sumption should be capable of yielding general

explanations of the anthropology of cuisine and the

microeconomics of the food market. The constructs

about cooking and eating held in common among

individuals from a social group are evidence of their

shared culinary culture. The effects of price, pack

label, and shelf display on the personal disposition

to purchase a food item will aggregate across con-

sumers into sales of that brand in the shops. The

performance of selective eating behavior provides

challenges to scientific explanation that go beyond

the physics and chemistry of foods and their biochem-

ical and physiological effects. Each individual has his

or her own causally structured behavior beyond the

food materials, the nutritional physiology, and the

socioeconomic systems.

0026Development of the quantitative behavioral science

of food choice and intake is needed. With fundamen-

tal understanding of the determinants of eating habits

at the level of the causal processes in the mind of the

consumer, we would be able to bring together know-

ledge of the socioeconomic, physicochemical, and

biochemical–physiological processes into a coherent

SATIETY AND APPETITE /Food, Nutrition, and Appetite 5101

science and effective practice of food design and diet-

ary health.

See also: Food Acceptability: Affective Methods;

Sensory Evaluation: Sensory Characteristics of Human

Foods; Food Acceptability and Sensory Evaluation;

Sensory Rating and Scoring Methods

Further Reading

Axelson ML and Brinberg D (1989) A Social–Psychological

Perspective on Food-Related Behavior. New York:

Springer-Verlag.

Barker LM (ed.) (1982) The Psychobiology of Human

Food Selection. Westport, Connecticut: AVI Publishing.

Bennett GA (1988) Eating Matters: Why We Eat What We

Eat. London: Heinemann Kingswood.

Berthoud H-R and Seeley RJ (eds) (2000) Neural and Meta-

bolic Control of Macronutrient Intake. Boca Raton:

CRC Press.

Boakes RA, Burton MJ and Popplewell DA (eds) (1987)

Eating Habits: Food, Physiology and Learned Behav-

iour. Chichester: John Wiley.

Bolles RC (1980) Historical note on the term ‘appetite’.

Appetite 1: 3–6.

Booth DA (ed.) (1978) Hunger Models: Computable

Theory of Feeding Control. London: Academic Press.

Booth DA (1994) Psychology of Nutrition. Bristol, PA &

London: Taylor & Francis.

Booth DA, Mobini S, Earl T and Wainwright CJ (2003)

Consumer-specified instrumental quality of short-

dough cookie texture using penetrometry and break

force. Journal of Food Science (in press).

Chivers DJ, Wood BA and Bilsborough A (eds) (1984) Food

Acquisition and Processing in Primates. New York:

Plenum Press.

Dobbing J (ed.) (1987) Sweetness. London: Springer-Verlag.

Farb P and Armelagos G (1980) Consuming Passions: the

Anthropology of Eating. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Fieldhouse P (1986) Food and Nutrition: Customs & Cul-

ture. London: Croom Helm.

Freeman RPJ, Richardson NJ, Kendal-Reed MS and Booth

DA (1993) Bases of a cognitive technology for food

quality. British Food Journal 95(9): 37–44.

Logue A (1991) The Psychology of Eating and Drinking,

2nd edn. New York: WH Freeman.

Meiselman HL (ed.) (2000) Dimensions of the Meal. The

Science Culture, Business and Art of Eating. Aspen, CO:

Aspen Publishers Inc.

Murcott A (ed.) (1983) The Sociology of Food and Eating.

Cardiff: Gower Press.

Ramsay DJ and Booth DA (eds) (1991) Thirst: Physio-

logical and Psychological Aspects. London: Springer-

Verlag.

Solms J and Hall RL (eds) (1981) Criteria of Food Accept-

ance: How Man Chooses What he Eats. Zurich: Forster.

Solms J, Booth DA, Pangborn RM and Raunhardt O (eds)

(1987) Food Acceptance and Nutrition. London:

Academic Press.

The Role of Satiety in Nutrition

D A Booth, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston,

Birmingham, UK

This article is reproduced from Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Copyright 1993, Academic Press.

Introduction

0001Satiety, a transient lack of interest in further inges-

tion, is a dispositional state of the individual. This

state may limit how much food and drink is con-

sumed on one occasion. It may also delay the next

occasion of consumption. The satiating effect of a

food is thought to contribute to that food’s accept-

ability, by serving as part of the satisfaction to be

gained from eating it. However, there are few relevant

hard data, and thinking on this matter is confused.

Scientific Concept of Satiety

0002Satiety is specifically the inhibitory effect of dietary

consumption on appetite. The decrease in hunger or

thirst must, by definition, have been caused by some

consequence of ingestion. In studies of satiety it is not

sufficient to record satiety ratings alone. These may

be graded expressions of the sensation of abdominal

fullness, the wish to eat only a small amount, an

awareness of how much was eaten and how recently,

or some other measure of the disposition to refuse

food. The origins of the lack of appetite must be

shown to include an effect of eating for the rating to

be a true measure of satiety. (See Satiety and Appetite:

Food, Nutrition, and Appetite.)

0003Scientific analysis of satiation requires identifica-

tion of the influence(s) from eating that reduce appe-

tite. Satiety is not a response but the operation of a

type of mechanism.

What Role does Satiety have in Food

Acceptability?

0004It is reasonable to expect that short-term satisfaction

of hunger by particular foods increases the accept-

ability of those foods. Another attraction of a food

or meal could be a longer postponement of the need

to eat. Understanding satiety mechanisms could be

considered to have broad relevance to the formula-

tion and marketing of foods.

0005However, there has so far been little scientific in-

vestigation in humans of the role of satiety in palat-

ability and choice of foods. A considerable body of

data in experimental animals has shown that the

satiating effect of eating food carbohydrate induces

sensory preferences for foods eaten shortly before

5102 SATIETY AND APPETITE /The Role of Satiety in Nutrition

absorption of the carbohydrate begins. Sensory pref-

erences are also acquired by association with the

effects of absorption of amino acids and of digested

fat, under conditions where it is less clear that these

nutrients are contributing to satiety. Experiments in

humans on the acquisition of sensory preference by

association with carbohydrate or protein also indi-

cate that satiety may influence the learning of palat-

ability. (See Sucrose: Dietary Importance.)

What Role does Satiety have in Weight

Control?

0006 Satiety is widely assumed to play a major role in

weight control. However, there is a dearth of data

on the mechanisms by which satiety can inhibit food

consumption in the short term, or on how such effects

influence energy intake and long-term energy bal-

ance. Research methods are not generally attuned to

the concept of satiety as a disposition integrated from

sensory, physiological, and cultural mechanisms, or

to daily energy intake as an epiphenomenon of di-

verse sequences of complex dietary selection deci-

sions. (See Obesity: Treatment.)

0007 As a result, satiety mechanisms are not effectively

exploited in established ways of attempting weight

control. This is a potential explanation for the fact

that obesity has not been prevented, and generally

reliable procedures have not been found to reduce

unhealthy overweight. There are sound reasons for

expecting satiety to have some part to play in weight

control. The satiating effects of foods or meals could

operate within the framework of certain patterns of

eating in ways that help to reduce habitual daily

intake, making excess energy intake over expenditure

less likely.

0008 Understanding satiety mechanisms is crucial for

extrapolating to common eating patterns in order to

identify foods and drinks that support successful

long-term weight control. Unfortunately, most fre-

quent research on human satiety has attempted only

to test foods and food components for effects on

appetite ratings and nutrient intake, without measur-

ing the foods’ mechanisms of action or their effects on

eating habits. As a result, the role of satiety in weight

control remains largely a matter of speculation.

Food-Specific Satiety Mechanisms

0009 Satiety is essentially sensory: it is a disposition to

reject foods or to accept them in limited amounts. In

principle, inhibition of eating could be similarly

strong for all foods. Alternatively, it is conceivable

that the strength of inhibition may vary with the

sensed identity of the food. Such satiety with a degree

of specificity to a food is called sensory-specific sati-

ety. The Greek form of this term was applied to a

taste-selective satiety that is claimed to depend on the

nutrient consumed: negative alliesthesia (literally, a

change in sensation – negative in the sense that the

food is less attractive). The sensory impression does

not necessarily change; the loss of interest is not be-

cause the taste seems weaker or different in gustatory

quality. The change is in the reaction to the taste (or

other sensory characteristics of the foodstuff).

0010There is evidence from experimental animals that

hypertonic sugar solutions (which can be nauseating

in people) cause a temporary loss of the sensual pleas-

ure obtained from sweetness. In humans, however,

suppression of a pleasurable reaction to foods has

yet to be distinguished from a reduced disposition to

consume them. Whether eating is motivated only by

pleasures and pains, or by other things as well, is an

empirical issue for cognitive psychology.

0011There are at least two sorts of food-specific satiety.

One is caused by immediately preceding exposure to

food having the consequently satiated sensory char-

acteristics. The other is a learnt reaction to those

sensory characteristics in conjunction with a particu-

lar physiological signal, such as a partly filled stom-

ach: it is not necessary for the particular food to have

been ingested previously in that meal; the reaction is

acquired from experience at one or more earlier

meals.

Habituation Satiety

0012Satiation for a food induced by recent exposure to

that food meets the basic criteria for the behavioral

change known as habituation. This is a decline in a

specific response (eating) during and shortly after

repeated or continuous exposure to a specific stimu-

lus (the food). The decline is not fatigue in the sensory

pathways or in the eating movement circuits but in-

volves a decline in effectiveness of central connections

between these two neural systems. At the sensory end

the rated strength of the sensation of, for example,

flavor does not decrease, at least not by as much as

the decrease in the rated pleasantness of eating the

food.

0013Introduction of a new stimulus disrupts habitu-

ation and the original response reemerges, an effect

called dishabituation. In the case of satiety, this dis-

ruption is known as the variety effect. Presenting a

food that was not in the preceding meal can reactivate

eating and its rated pleasantness. Switching foods can

provoke eating a larger meal than switches between

samples of the same food in experiments with rats

and with human subjects.

0014If the larger meal is compensated by omission of a

subsequent snack or by a smaller following meal,

SATIETY AND APPETITE /The Role of Satiety in Nutrition 5103

body weight should not be affected. There is no con-

clusive evidence that marketing a wide variety of

flavor variants contributes to obesity.

0015 The mental processes involved in habituation sati-

ety remain to be elucidated. Boredom with a food

seems to be more complex than mere fatigue in a

central neuronal connection; yet it could still be

based on a subconscious decline in a particular sens-

ory facilitation of eating.

0016 Habituation in invertebrates is mediated by a de-

cline in effectiveness of synapses on the motor

neurons from the repeatedly stimulated sensory path-

way. Similarly, taste-specific satiation in monkeys in-

volves no changes in the taste pathways through to

the cerebral cortex: changes in line with the satiated

behavior occur only beyond the sensory cortex, to-

wards the food-selection pathways.

0017 Habituation also has a long-term component. The

short-term habituated response recovers completely

within an hour or so of the end of repeated stimula-

tion. When the same stimulus is repeatedly presented

on a later occasion, the decline in response is more

rapid. Long-term habituation (i.e., more rapid reha-

bituation) may contribute to boredom with the same

meal presented day after day.

0018 There are indications of the more complex pro-

cesses in the attractions of long-term variety. While

the main item that characterizes a course in a meal

might have to be varied, the same staple food (such as

potatoes or bread) can be eaten day after day. In

addition, drinks seem to show less item-specific sati-

ation than many foods. Conventions about menus or

personal dietary habits may contribute to cessation of

eating one food or to starting to eat a different food.

0019 Famine relief may provide only two or three food-

stuffs, albeit in ample quantities. This diet might

become tedious even to the chronically hungry

who are being offered culturally appropriate staples.

There is some evidence that intake increases when

a variety of flavorings is provided with the basic

commodities.

Conditioned Satiety

0020 The second known type of food-specific satiety has

been learned from experiences in the past. Satiety

learning processes have the basic form of associative

conditioning – stimuli elicit a reaction that they have

not previously evoked, because they have been asso-

ciated with consequent stimuli. Repetition is not

enough; the stimuli must be paired with conditioning

consequences.

0021 The Russian behavioral physiologist Pavlov demon-

strated conditioning of appetite when the ringing of a

bell in hungry dogs was paired with feeding or a food

taste; after that, ringing the dinner bell when the dogs

had empty stomachs elicited salivation and orienta-

tion to the food provider or food bowl before the food

was presented. The bell and the empty stomach pre-

dict the taste of food. The dog associated this cue or

conditioned stimulus (CS) with the consequence or

unconditioned stimulus (US).

0022The conditioning of satiety follows the same prin-

ciples. A food stimulus and a partly filled stomach

(the CS) are paired with subsequent strong satiation,

such as a mildly bloated sensation (the US). When

the food or flavor is presented again later, while the

stomach is just as full, the food flavor has become less

attractive or even slightly repulsive. To the extent that

this loss of interest comes to consciousness, it will

be expected that particular foods or meals will be

regarded as satisfying.

0023A key difference from habituation satiety is that

conditioned satiety does not depend on the sensory

characteristics of the food that has just been eaten.

The loss of interest can apply to a food that had not

been presented before on that particular occasion,

because the satiety had been learned on earlier occa-

sions. All foods to which satiety has been previously

conditioned will become less attractive when the

stomach begins to fill.

Integration of Satiety Processes

0024Conditioned elicitation of loss of interest in eating by

cues from food and from the digestive tract suggests

that satiety in familiar situations is a learnt response.

If internal signals can become part of the food-specific

satiating pattern, external cues such as emptied plates

may also come to suppress appetite.

0025Experiments on satiety risk missing the normal

mechanisms of satiety when they impose unfamiliar

or extreme conditions. Eating would stop when

visceral or social discomfort is strong enough, inde-

pendently of prior learning. Therefore, to elucidate

postingestional and social satieties, the role of any

one satiety mechanism must be examined in its

normal range and within the learnt complex a person

has established for his or her dietary habits.

Postingestional Satiety Mechanisms

0026The effects of food arise in sequence as the ingested

food passes down the digestive tract, from sight and

aroma, through texture, temperature, irritation,

taste, and retronasal aroma in the mouth, to stimula-

tion of the gut wall, and the stimulation of tissues

such as the liver and the brain itself as the food is

absorbed. The traditional assumption in the physi-

ology of ingestion has been that inhibitory stimuli

subtract from facilitatory stimuli. Intake of sugar

solutions in rats has an intestinal effect which

5104 SATIETY AND APPETITE /The Role of Satiety in Nutrition

subtracts from the palatability of the sweetness;

however, these fluids are not familiar parts of the

subjects’ diet.

0027 Linear or additive interactions are not the norm in

neurophysiological studies, or in experiments on the

interactions of mechanisms in the ingestion or rating

of ordinary foods and drinks. There is no convincing

evidence for interactions among satiety mechanisms

that justify the use of the term cascade. The evidence

is consistent with satiety arising from recognition of

the accustomed pattern of eating, postingestional

stimulation, and social constraints, with reduced sati-

ety in the absence of any one element in that learnt

pattern.

Cultural and Interpersonal Satiety Mechanisms

0028 Appropriate proportions of food items on a plate

(e.g., meat and vegetables) and the total amount

(e.g., for a man or at the price) are subject to cultural

variation, although these in turn may be influenced by

average physiological requirements.

0029 The process of eating in company can influence

food intake. For example, a dieter may inhibit eating.

This social satiety for food is likely to have been

integrated with physiological and sensory satiety, at

least in situations about which sufficient has been

learned from personal experience.

Satiety Disruption in Dieting

0030 Reducing dietary intake may evoke desires for more

food and, possibly, cravings for forbidden foods. Cog-

nitive bases for food cravings are more likely than

hormonal imbalances or nutrient deficiencies.

0031 Small meals are less likely to create satiety and will

allow the hunger pattern in the viscera and within the

memory of that meal to form sooner than after a

larger meal. Sufficiently severe restriction of food at

meals, even when the gut and the tissues adapt, will

activate innate mechanisms of distress, readily

labeled hunger by the dieter. The temptation to look

for food will be increased, as will the temptation to

eat when food is available.

Satiety Manipulation in Weight Control

0032 Permanently successful weight control will depend on

keeping satiety as normal as possible in the new life-

style required to maintain target weight.

Satiety Synapses and Antiobesity Drugs

0033 The pathways in the brain over which the inhibitory

effects of food on eating are transferred are poorly

understood. Satiety signals, such as distension of the

stomach, chemical stimulation of the upper intestine,

and oxidation of energy substrates in the liver, have

been investigated in isolation from stimuli from food.

Reactions to these food stimuli constitute the dispos-

ition to eat that satiety suppresses. Neural signals

from the viscera and sensors of the circulation at the

surface of the brain have their first relay at the back of

the brainstem. It is not known where or how they

interact there and higher in the brain with the sensory

control of eating in the inhibition of appetite.

0034Visceral signals are relayed to the hypothalamus at

the head of the brainstem; this has complex connec-

tions with the forebrain, where incoming and past

information from different sources is put together.

For example, gastric distension affects neuronal ac-

tivity in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Yet

this is not evidence that this region mediates satiety,

because the hypothalamus has many autonomic and

endocrine functions to perform. These are liable to

affect eating behavior indirectly (via neural circuitry

elsewhere in the brain). In fact, it has been found that

the ventromedial hypothalamic region is not crucial

to any of the appetite-suppressant effects of food that

have been tested.

0035These tests were carried out to evaluate the theory

that the obesity seen after destruction of this region of

the hypothalamus arises from a defect in satiety

resulting from destruction of ‘the satiety center.’

Since satiety mechanisms operate normally in rats

made fat by lesions in this area, the hypothalamus is

unlikely to contain any such center.

0036The effects of drugs on the sizes of meals in experi-

mental animals have inspired theories that particular

monoamine neurotransmitters operate in the path-

ways on the brain that mediate satiety. A region of

the hypothalamus forward from, and above, the ori-

ginally supposed satiety and appetite centers appears

to contain some of the synapses at which transmission

alters meal sizes.

0037Norepinephrine (noradrenaline) appears to be the

transmitter at synapses in this region that increases

meal sizes and even restarts eating in a satiated

animal. Analysis of the different possible mechanisms

implicates a disruption of conditioned satiety.

0038However, it may be a localized effect of the arousal

system that has norepinephrine (noradrenaline) syn-

apses in many brain regions. This may be experimen-

tal isolation of the effect of distraction or excitement

on normal moderation of eating. Conceivably, there-

fore, disruption of learnt satiety is related to emo-

tional eating. This is amenable to psychological

management and does not need drug treatment.

0039Drugs that activate synapses using serotonin (5-

hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) decrease the size of the

first meal that a rat takes after it has been deprived

SATIETY AND APPETITE /The Role of Satiety in Nutrition 5105

of food for a while. This has been interpreted as an

augmentation of satiety. However, starved rats tend

to eat fast and long at this initial meal. Serotonin is

a transmitter in the brainstem circuits that organize

chewing and other tactually guided movements.

Hence these drugs may simply be slowing move-

ment or making chewing and swallowing more diffi-

cult; they have been shown to alter the effects of food

textures on preference and intakes in rats. Serotonin

is also important in sleep circuits; indeed, when these

drugs are having their greatest impact on people’s

eating, they are also having their strongest sedative

effect. The classic meal-size decrease in these circum-

stances may have nothing to do with satiety.

0040 Serotonergic drugs that have been used to aid rapid

weight reduction may exert part of their effect per-

ipherally. Serotonin is one of the most important

transmitters in local neural control of the contrac-

tions that pass food down the digestive tract. These

and other drugs therefore slow gastric emptying

under some conditions, prolonging the satiating

action of food and reducing the temptation to

snack. They may even postpone the next meal.

Satiety in Dietary Treatment and Advice

0041 There is a medical consensus that energy from starchy

foods should not be decreased. Where energy is

needed to replace that removed by reduction in fat

intake, starch intake should be increased. Readily

assimilated carbohydrate, particularly in the earlier

stages of meals, is likely to play a major role in

immediate satisfaction following the meal. This func-

tion and its training of expectations and palatability

are important for acceptability of the diet.

0042 In addition, intake of low-energy bulky foods, such

as pulses, grains, and vegetables and fruit that provide

nonstarch polysaccharides, is recommended. The sa-

tiating effect of normal amounts of fiber is probably

mediated by learning by association with intestinal

and metabolic effects such as those of glucose and

fructose from the starch and sugar present in high-

fiber foods. Therefore the sugar that is often required

to make high-fiber foods edible also has a role in their

satiating effects. Alternatively, some of the starch may

be rapidly assimilated. However, much of the starch

will be in slowly assimilable forms, potentially delay-

ing the return of hunger.

0043 Enthusiasm for a nutrient, a diet product, or a

dietary regimen by a professional or in another dieter

can convey itself to the dieter or at least lead to it

being tried in desperation. For example, it seems ob-

vious that high-fiber foods are filling, and these foods

have acquired a nutritious image. This sensory satiety

can suggest visceral satiety, and these expectations

may be fulfilled as long as sufficient energy is included

with the fiber. The assumption is that sufficiently high

doses of fiber augment satiety by postingestional

mechanisms such as slower gastric emptying and

slower absorption of nutrients through soluble fiber

gels in the small intestine. These theories remain to be

critically tested, by studies of normal eating with

sensory factors dissociated out.

Satiety in Psychological Weight Therapy

0044Eating slowly is a standard part of behavior modifi-

cation for weight reduction, although its effectiveness

has not been evaluated.

0045Part of the rationale has been to ‘satisfy the taste

buds.’ Perhaps savoring all the food that is eaten helps

to ward off the sense of restriction that makes forbid-

den eating more tempting. Another idea is that more

prolonged sensing would augment food-specific

satiety.

0046A different rationale for slow eating has been that it

would fill the stomach more effectively and so satiate

with less food. However, there is no evidence that

gastric distension plays such a precise or dominant

role in meal termination. Furthermore, if the eating

were as slow as gastric emptying, the stomach would

not begin to fill.

0047A variety of other suggestions have been made as to

how to strengthen the influence of satiety but none

has yet been taken up seriously, let alone tested for

efficacy.

See also: Obesity: Treatment; Sucrose: Dietary

Importance

Further Reading

Bennett GA (1986) Behavior therapy for obesity: a quanti-

tative review of the effects of selected treatment charac-

teristics on outcome. Behavior Therapy 17: 554–562.

Berthoud H-R and Seeley RJ (eds) (2000) Neural and Meta-

bolic Control of Macronutrient Intake. Boca Raton:

CRC Press.

Bolles RC (ed.) (1991) The Hedonics of Taste. Hillsdale,

New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Booth DA (1994) Psychology of Nutrition. London: Taylor

& Francis.

Booth DA (1998) Promoting culture supportive of the least

fattening patterns of eating, drinking and physical activ-

ity. [Prevention of Obesity: Berzelius Symposium and

8th International Congress of Obesity Satellite.] Appe-

tite 31: 417–420.

Booth DA, Rodin J and Blackburn GL (eds) (1988) Sweet-

eners, Appetite and Obesity (supplement to Appetite).

London: Academic Press.

Capaldi ED and Pawley TL (1990) Taste, Experience, and

Feeding. Washington, DC: American Psychological

Association.

5106 SATIETY AND APPETITE /The Role of Satiety in Nutrition