Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

See also: Carbohydrates: Classification and Properties;

Digestion, Absorption, and Metabolism; Requirements

and Dietary Importance; Children: Nutritional

Requirements; Community Nutrition; Energy:

Measurement of Food Energy; Measurement of Energy

Expenditure; Energy Expenditure and Energy Balance;

Food Composition Tables; Growth and Development;

Infants: Nutritional Requirements; Metabolic Rate;

Nutrition Policies in WHO European Member States;

Pregnancy: Metabolic Adaptations and Nutritional

Requirements; World Health Organization

Further Reading

Black AE (1996) Physical activity levels from a meta-analy-

sis of doubly labelled water studies for validating energy

intake as measured by dietary assessment. Nutrition

Reviews 54: 170–174.

Black AE (2000) Critical evaluation of energy intake using

the Goldberg cut-off for energy intake: basal metabolic

rate. A practical guide to its calculation, use and limita-

tions. International Journal of Obesity 24: 1119–1130.

Black AE and Cole TJ (2000) Within- and between-subject

variation in energy expenditure measured by the doubly-

labelled water technique; implications for validating

reported dietary energy intakes. European Journal of

Clinical Nutrition 54: 386–394.

Black AE, Coward WA, Cole TJ and Prentice AM (1996)

Human energy expenditure in affluent societies: an

analysis of 574 doubly-labelled water measurements.

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 50: 72–92.

Black AE, Goldberg GR, Jebb SA et al. (1991) Critical

evaluation of energy intake data using fundamental prin-

ciples of energy physiology. 2. Evaluating the results of

dietary surveys. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition

45: 583–599.

Black AE, Prentice AM, Goldberg GR et al. (1993) Meas-

urements of total energy expenditure provide insights

into the validity of dietary measurements of energy

intake. Journal of the American Dietetic Association

93: 572–579.

Butte NF (1996) Energy requirements of infants. European

Journal of Clinical Nutrition 50 (supplement 1): S24–

S36.

Department of Health (1991) Dietary Reference Values for

Food Energy and Nutrients for the United Kingdom.

London: The Stationery Office.

FAO/WHO/UNU (1985) Report of a Joint Expert Consult-

ation: Energy and Protein Requirements. Technical

Report Series 724. Geneva: WHO.

Finch S, Doyle W, Lowe C et al. (1998) National Diet and

Nutrition Survey: People Aged 65 Years and Over.

Volume 1: Report of the Diet and Nutrition Survey.

London: The Stationery Office.

Fogelholm M, Kolset SO, Rasmussen LB, Sjostrom M and

Yngve A (2000) Physical activity – an essential part of

dietary recommendations? Scandinavian Journal of

Nutrition 44: 69–70.

Goldberg GR, Black AE, Jebb SA et al. (1991) Critical

evaluation of energy intake data using fundamental

principles of energy physiology. 1. Derivation of cut-off

limits to identify under-recording. European Journal of

Clinical Nutrition 45: 569–581.

Gregory JR, Collins DL, Davies PSW, Hughes JM and

Clarke PC (1995) National Diet and Nutrition Survey:

Children Aged 1 to 4 Years. Volume 1: Report of the

Diet and Nutrition Survey. London: The Stationery

Office.

Gregory J, Foster K, Tyler H and Wiseman M (1990) The

Dietary and Nutritional Survey of British Adults.

London: The Stationery Office.

Gregory J, Lowe S, Bates CJ et al. (2000) National Diet and

Nutrition Survey: Young People Aged 4 to 18 Years.

Volume 1: Report of the Diet and Nutrition Survey.

London: The Stationery Office.

Macdiarmid J and Blundell J (1998) Assessing dietary

intake: who, what and why of under-reporting. Nutri-

tion Research Reviews 11: 231–253.

Prentice AM, Spaaij CJK, Goldberg GR et al. (1996) Energy

requirements of pregnant and lactating women. Euro-

pean Journal of Clinical Nutrition 50 (supplement 1):

S82–S111.

Price GM, Paul AA, Cole TJ and Wadsworth MEJ (1997)

Characteristics of the low-energy reporters in a longitu-

dinal national dietary survey. British Journal of Nutri-

tion 77: 833–851.

Roberts SB (1996) Energy requirements of older individ-

uals. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 50 (supple-

ment 1): S112–S118.

Schoeller DA (1990) How accurate is self-reported dietary

energy intake? Nutrition Reviews 48: 373–379.

Shetty PS, Henry CJK, Black AE and Prentice AM (1996)

Energy requirements of adults: an update on basal meta-

bolic rates (BMRs) and physical activity levels (PALs).

tbl0009 Table 9 Summary of physical activity levels (PALs) calculated from doubly labelled water measurements of total energy expenditure

Overall activity PAL

Chair-bound or bed-bound 1.2

Seated work with no option of moving around and little or no strenuous leisure activity 1.4–1.5

Seated work with discretion and requirement to move around but with little or no strenuous leisure activity 1.6–1.7

Standing work (e.g., housewife, shop assistant) 1.8–1.9

Significant amounts of sport or strenuous leisure activity (30–60 min, four or five times per week) þ0.3

Strenuous work or very active leisure 2.0–2.4

Source: Black AE, Coward WA, Cole TJ and Prentice AM (1996) Human energy expenditure in affluent societies: an analysis of 574 doubly-labelled water

measurements. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 50: 72–92.

ENERGY/Intake and Energy Requirements 2097

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 50 (supplement

1): S11–S23.

Starling RD and Poehlman ET (2000) Assessment of energy

requirements in elderly populations. European Journal

of Clinical Nutrition 54 (supplement 3): S104–S111.

Torun B, Davies P, Livingstone M et al. (1996) Energy

requirements and dietary energy recommendations for

children and adolescents 1 to 18 years old. European

Journal of Clinical Nutrition 50 (supplement 1):

S37–S81.

Measurement of Energy

Expenditure

P R Murgatroyd, University of Cambridge,

Cambridge, UK

W A Coward, MRC Human Nutrition Research,

Cambridge, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 The energy that drives endogenous chemical pro-

cesses and the performance of external mechanical

work is released from the macronutrients fat, carbo-

hydrate, and protein by oxidation and ultimately

dissipated as heat. Energy expenditure may thus be

measured either directly, by estimating the energy

dissipated as heat, or indirectly, by measuring the

rates of macronutrient oxidation. The associated

measurement techniques are termed direct and indir-

ect calorimetry, respectively. This article describes the

ways in which measurements of energy expenditure

may be made and discusses the factors influencing

their accuracy and precision.

0002 The most accurate and precise primary energy

measurement techniques impose constraints on the

individual being studied, but these may be turned to

advantage in studies that require closely controlled

conditions. Where an estimate of free-living energy

expenditure is required, secondary indirect tech-

niques, lacking the quality of the primary measure-

ments but relying on them for verification or

standardization, must be used. These include the esti-

mation of carbon dioxide production from the elim-

ination rates of the stable isotopes

2

H and

18

O, and

the estimation of energy expenditure from measure-

ments of heart rate or from records of activity.

Direct Calorimetry

0003 Heat is dissipated from the body by nonevaporative

routes (by radiation, conduction and convection)

and evaporative routes (through respiratory and

perspiratory water loss). These components are esti-

mated, together with the heat generated in external

work, by measuring the fluxes of heat from a calor-

imeter, a ventilated room that contains the subject.

The nonevaporative heat flux is generally measured

by one of two techniques, gradient layer or heat sink

calorimetry. Evaporative heat flux measurements

are made either by condensing the evaporated water

or by measuring the water vapor added to the venti-

lating air.

Nonevaporative Heat-loss Measurement

0004-Gradient-layer calorimetry Gradient-layer calor-

imetry measures the flux of heat through the walls

of the calorimeter. The walls are constructed of a thin,

rigid material such as glass-reinforced epoxy resin. As

heat produced by a subject flows out through the

wall, a temperature gradient is established across the

wall. This is measured by temperature-sensing layers

distributed over the inner and outer wall surfaces.

These layers may be resistance thermometers, formed

by etching copper films bonded to each side of the

wall material, or may be in the form of a thermopile

with ‘hot’ junctions on one side of the wall and ‘cold’

junctions on the other. The relationship between the

mean wall temperature gradient and heat flux is

found empirically by calibration with known heat

inputs to the calorimeter. To ensure that the heat

flux measured arises only from the subject, the rate

of change of the heat content of the calorimeter must

be very much less than the heat flux from the subject.

This is generally achieved by fixing the outside tem-

perature of the wall with a water jacket, the water

temperature being controlled to avoid rates of change

of water temperature exceeding 0.001

C min

1

.

0005-Heat-sink calorimetry A heat-sink calorimeter

measures the nonevaporative heat lost by a subject

in terms of the rate at which heat must be removed

from the calorimeter to prevent air-temperature rise

and associated heat loss through the calorimeter

walls. The heat is removed by recirculating the calor-

imeter air over a water cooled heat exchanger. Ther-

mal insulation makes the temperature gradient across

the walls very responsive to changes in heat produc-

tion within the calorimeter. This gradient is sensed

and used to control the temperature of water entering

the heat exchanger so that it removes heat at a rate

which minimizes heat losses through the walls and

thus equals the heat flux from the subject. The heat

flux is expressed as:

Q

e

¼

t

e

t

s

xQ

s

2098 ENERGY/Measurement of Energy Expenditure

where Q

e

is the heat extracted from the calorimeter,

Dt

e

is the rise in temperature of the water flowing

through the heat exchanger, Dt

s

is the rise in tempera-

ture of the same water passing through a standard

heater, and Q

s

is the heat input to the standard heater.

0006 As with the gradient layer calorimeter, the rate of

change of heat content of the calorimeter must be

minimized, but due to the higher thermal insulation

of the heat sink calorimeter’s walls, this can be

achieved by controlling the temperature of the air

surrounding it to + 0.25

C, avoiding the need for a

water jacket.

Evaporative Heat-loss Measurement

0007 -Condensation measurements Ventilating air is con-

ditioned prior to entering the calorimeter. It is first

saturated, then cooled to a constant dew point tem-

perature by a water-cooled heat exchanger, then

reheated to the calorimeter temperature. Air leaving

the calorimeter is passed over an identical heat ex-

changer to return it to its initial dew point tempera-

ture. The heat extracted from the outgoing air is the

evaporative heat loss plus a nonevaporative compon-

ent, which may be deduced either from measurements

of ventilation air flow rate and temperature or by

measuring the heat added to the air after the ingoing

heat exchanger to bring it to the calorimeter tempera-

ture. Corrections must be made to the evaporative

heat loss measurement for the difference between the

latent heats of evaporation at body temperature and

the condensation temperature.

0008 -Vapor-phase measurements The rate of evapora-

tive heat loss can be expressed as the product of the

rate of vapor production and the latent heat of vapor-

ization. Water-vapor production within the calorim-

eter is calculated from measures of in- and out-going

vapor pressure, total (atmospheric) pressure, and the

flow rate of the calorimeter ventilating air. The vapor

pressure is best deduced from dewpoint temperature,

which can be measured to + 0.1

C using commercial

instruments.

Strengths and Limitations of Direct Calorimetry

0009 Measurements of total heat production in direct calor-

imeters can be of very high quality, certainly yielding

results reproducible to within + 1% of calibration

standards. Response times are also very rapid, particu-

larly for gradient-layer systems using condensation

techniques to measure the evaporative heat compon-

ent. The accurate partition of heat loss into evapora-

tive and nonevaporative components is difficult to

demonstrate, as some of the latent heat of vaporization

may be supplied by the environment rather than the

subject. Direct calorimetry can be something of an

engineering tour de force, which in part explains the

move towards indirect calorimetry in recent years.

There are also operational difficulties. Heat dissi-

pated within the calorimeter from sources other

than the subject must be accurately measured. These

sources, which include radiant heat exchanges

through windows, heat dissipated from meals and

drinks before they are consumed, and heat lost from

excreta, may contribute as much as 15% of the total

measured heat. Direct calorimetry still has an import-

ant role in combination with indirect calorimetry in

the study of heat balance, but this is currently a rela-

tively minor area of research interest. For studies of

energy regulation, indirect calorimetry has displaced

direct calorimetry because of its overriding advantage

of adding to the measurement of energy expenditure

the measurement of the oxidation rates of the individ-

ual energy macronutrients.

Indirect Calorimetry

0010Indirect calorimetry measures energy expenditure by

estimating the oxidation rates of the energy macronu-

trients, fat, carbohydrate, and protein, from rates

of respiratory exchange of oxygen and carbon diox-

ide and from the excretion in urine of incompletely

oxidized nitrogenous compounds. The respiratory

exchanges may be measured in air directly respir-

ed through a mask or mouthpiece, in the air flowing

through a ventilated canopy over the subject’s head or

in the air ventilating a small room in which the sub-

ject may live for some time. The measurements and

calculations required are essentially the same for all

these cases.

Gas-exchange-rate Measurements

0011The variables that must be measured to calculate

oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange rates at standard

temperature and pressure (STP) under dry conditions

are: the ventilation rate of the subject or his enclosure,

the concentrations of oxygen and carbon dioxide in-

spired and expired by the subject or entering and

leaving the enclosure, and the moisture content, tem-

perature, and pressure of the ventilating air at the

point where its flow rate is measured. It is assumed

that the only gaseous variables are oxygen, carbon

dioxide, and water vapor, i.e., that nitrogen and the

minor components of air are not metabolically active.

Rates of gas exchange in directly respired air or in

small ventilated canopies are calculated in terms of

the product of the ventilation rate and the gas concen-

tration changes generated by the subject as:

R

G

¼ F

o

C

o

f

N

2

o

f

Go

=f

N

2

o

f

Gi

=f

N

2

i

ðÞ,

ENERGY/Measurement of Energy Expenditure 2099

where the outgoing ventilation flow rate is measured

and:

R

G

¼ F

i

C

i

f

N

2

i

f

Go

=f

N

2

o

f

Gi

=f

N

2

i

ðÞ

,

where ingoing ventilation flow rate is measured. F is

the ventilation rate, C is the correction to STP dry

conditions, and f is the fractional concentration of a

gas. The subscripts i and o indicate in- and outgoing

samples. N

2

refers to nitrogen and the inert compon-

ents of air, deduced by the difference from O

2

and

CO

2

measurements.

0012 When measurements are made in a room, this

simple approach yields results that do not immedi-

ately reflect the gas exchanges of the subject. An

additional term, the product of the calorimeter

volume and the rate of change of gas concentration,

is needed to account for the rate at which the volume

of oxygen or carbon dioxide stored within the room

air is changed by the subject. With the addition of this

term, and with highly precise determination of

oxygen and carbon dioxide concentrations, useful

measurements of macronutrient oxidation rates and

energy expenditure can be made over periods as short

as 30 min in a room whose volume is 150 times

greater than that of the subject within it.

Measurement of Macronutrient Oxidation Rates

0013 Protein oxidation is an incomplete process yielding

nitrogenous compounds, urea, uric acid, and ammo-

nia, which are excreted in urine. The nitrogen in urine

may be measured by several techniques, but the most

commonly used procedure is the Kjeldahl method

(See Meat: Analysis). Protein oxidation is calculated

as 6.25 nitrogen excretion rate in grams. The

oxygen and carbon dioxide exchanges associated

with protein oxidation can be deduced from the coef-

ficients in Table 1. When these exchanges are sub-

tracted from the total respiratory gas exchanges, the

‘nonprotein’ exchanges remain, and from these, the

rates of fat and carbohydrate oxidation are calcu-

lated. The precisions achievable for fat and carbohy-

drate oxidation measurements made over 30 min

within a room calorimeter are typically + 0.4 and

+ 0.7 g. (Precision is estimated as +1 standard devi-

ation confidence limits from 20 repeated measures of

simulated gas exchange and nitrogen analysis.) The

accuracies are typically +0.2 and + 0.42 g, respect-

ively, for sedentary activity in an adult subject.

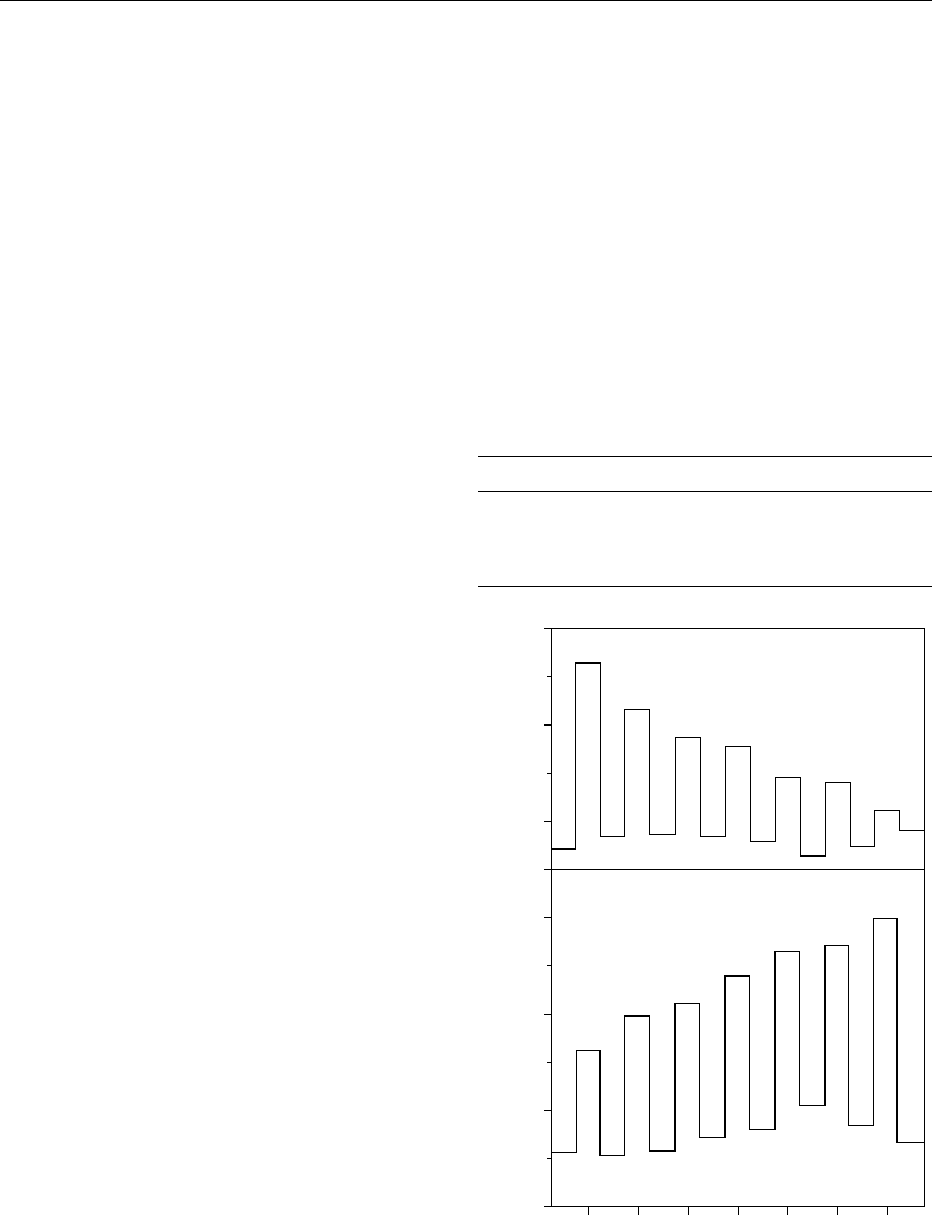

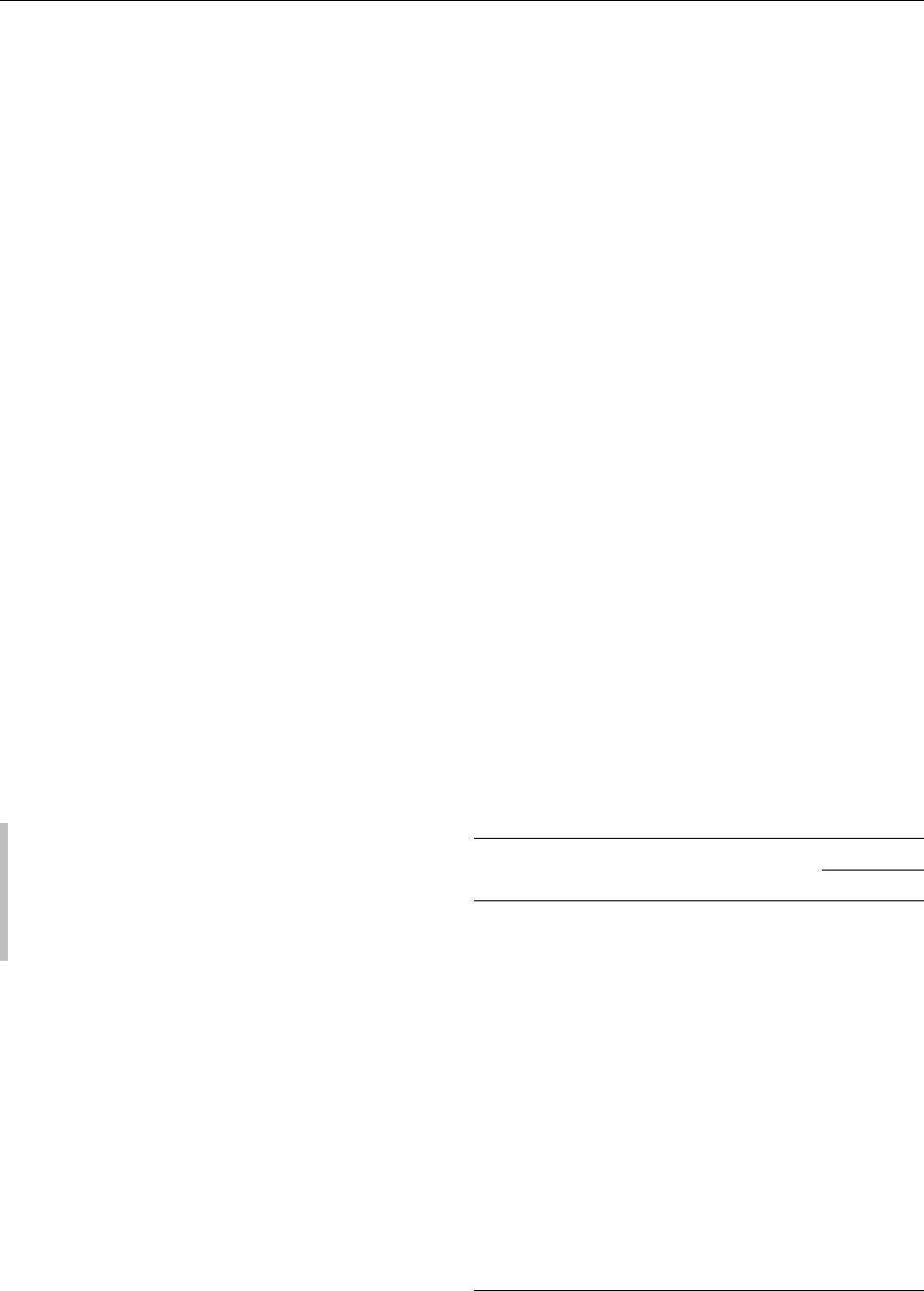

0014 Figure 1 illustrates macronutrient flux measure-

ments made by indirect calorimetry and the oxidation

rates of fat and carbohydrate measured during alter-

nating 30-min periods of exercise and rest. Measure-

ments were made within a whole-body calorimeter

room with an internal volume of 11 m

3

.

Calculation of Energy Expenditure

0015Once the macronutrient oxidation rates are known,

energy expenditure can be calculated from the

summation of the products of the macronutrients

oxidized and their energy densities (Table 1). The

accuracy of energy expenditure measurements

achieved in this way can be + 1% or better. Protein

oxidation often accounts for a small (12–15%) and

relatively constant proportion of total energy expend-

iture, and so energy expenditure may be estimated as:

EE ¼ 15:82 O

2

consumption

þ 5:21 CO

2

production,

where EE is in kJ min

1

, and gas exchanges are in

1 min

1

.

1234

Exercise period

Carbohydrate

Fat

Fat and carbohydrate oxidation (kJ min

−1

)

0

10

20

30

0

10

20

567

fig0001Figure 1 Oxidation rates of fat and carbohydrate measured by

whole body indirect calorimetry during alternating 30-min

periods of exercise and rest.

tbl0001Table 1 Macronutrient oxidation coefficients

Carbohydrate Protein Fat

Energy equivalent

of oxygen (kJ I

1

)

21.12 19.48 19.61

Respiratory quotient 1.0 0.835 0.71

Energy density (kJ g

1

) 15.76 18.56 39.33

2100 ENERGY/Measurement of Energy Expenditure

0016 The respiratory quotient (RQ) is the ratio of

carbon dioxide production to oxygen consumption

and reflects the relative contributions of fat, carbohy-

drate, and protein to the oxidation fuel mixture

(Table 1). The energy equivalent of 1 l of oxygen

consumed by fat, carbohydrate, or protein oxidation

is rather similar (Table 1). By assuming an RQ of 0.85

with 12.5% energy from protein oxidation, energy

expenditure can be estimated from oxygen consump-

tion alone as:

EE ¼ 20:3 O

2

consumption:

This remains accurate to within about + 2.5% over

the range of fat to carbohydrate oxidation ratios

normally encountered.

Measurement of Energy Expenditure in

Free-living Subjects

Doubly Labeled Water

0017 -Principles of the method In the previous section,

it was shown that energy expenditure can be esti-

mated from oxygen-consumption measurements.

Energy expenditure can also be expressed in terms

of measurements of CO

2

production, and this forms

the basis of the doubly labeled water method.

0018 The energy equivalence of carbon dioxide, in con-

trast to that of oxygen, varies significantly with the

mixture of macronutrients being oxidized. RQ could

range from 0.7, if fat were the source of all energy,

to 1.0, if all energy came from carbohydrate (see

Table 1). In practice, sustained average RQ values

outside the range 0.8–0.9 are rare, and for subjects

close to energy balance, RQ may be inferred with

greater confidence than this from knowledge of the

subject’s typical dietary composition. The energy

equivalence of CO

2

for a range of RQ values is

given in Table 2.

0019 Carbon dioxide production may be measured, and

hence energy expenditure estimated, from the differ-

ence between the disappearance rates of labeled

hydrogen and oxygen in body water. The origin of

the difference in isotope disappearance rates is the

carbonic anhydrase catalyzed exchange of oxygen in

water with oxygen in carbon dioxide (CO

2

). Labeled

oxygen can thus leave the body as either water or

carbon dioxide, while hydrogen can leave only as

water.

0020The volume of water in a body may be measured by

the dilution of isotopes in the body water pool, a

technique that has long been used for studies of

body composition. In this procedure, small amounts

of water labeled with stable isotopes of hydrogen or

oxygen (

2

Hor

18

O) are administered, usually orally,

and body-water volume calculated from the equation:

Isotope dilution space ¼ isotope given=

isotope concentration found:

This relationship assumes that isotope instantan-

eously distributes itself in body water in the same

way that a marker dye would distribute itself in a

flask of water. In practice, because body water is

continually being lost and replenished by water

intake, the isotope concentration falls in an exponen-

tial manner from its initial value. Because labeled

oxygen can leave the body as either water or carbon

dioxide, while hydrogen can leave only as water, each

isotope has an individual logarithmic slope for its

disappearance or rate constant (k

H

and k

O

)asmay

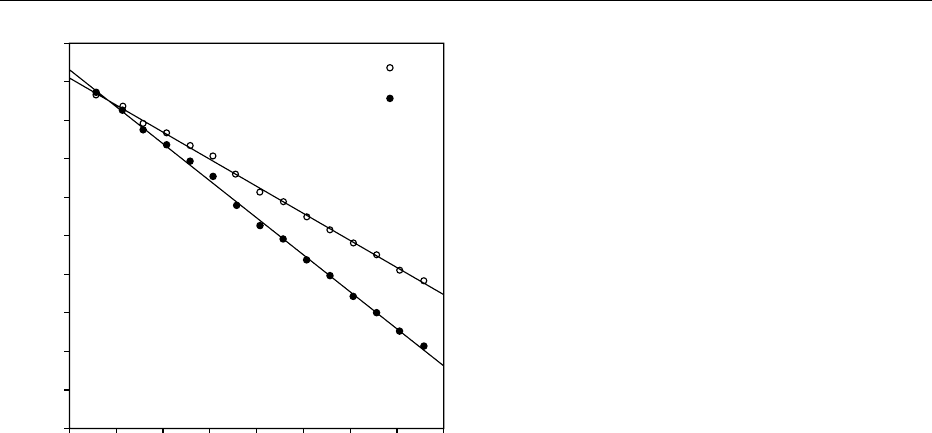

be seen in Figure 2. Furthermore, the isotope distri-

bution spaces (V

H

and V

O

) are slightly different,

principally because the hydrogen atoms in water

exchange rapidly with those in proteins.

0021The difference between the rates of disappearance

of labeled hydrogen and oxygen thus provides a

measure of carbon dioxide excretion or production,

r

CO

2

, which may be expressed as:

r

CO

2

¼ k

O

V

O

k

H

V

H

ðÞ=2 moles:

The factor of 2 arises because 1 mole of CO

2

is

equivalent to 2 moles of water.

0022To calculate CO

2

production rates, this basic equa-

tion is modified to allow for isotope fractionation

when losses occur as water vapor or CO

2

. There are

several ways in which this can be done, but the sim-

plest is to assume that water loss consists of a fraction-

ated component (r

f

) and an unfractionated component

(r

i

), and that r

f

is related to r

CO

2

. For adults in temper-

ate climates, r

f

¼ 2.1 r

CO

2

, in which case:

r

CO

2

¼

k

O

V

O

k

H

V

H

2f

3

þ 2:1 f

2

f

1

ðÞ

,

where f

1

, f

2

, and f

3

are fractionation factors for

2

H

and

18

O in water vapor and

18

OinCO

2

, respectively.

0023-The method in practice The procedure used in the

application of this method is that the subject first

provides a sample of their body water (e.g., a urine

tbl0002 Table 2 Energy equivalence of carbon dioxide for different

values of respiratory quotient

Respiratory quotient E

eq

CO

2

0.75 26.2

0.8 24.9

0.85 23.8

0.9 22.8

1.0 21.0

ENERGY/Measurement of Energy Expenditure 2101

sample) for the measurement of background isotope

levels. The isotope dose is then drunk, and samples of

urine produced over the next few days are retained

for analysis. As few as two samples are required, one

near the start of the experiment and one 2–3 bio-

logical half-lives of the isotopes later, though preci-

sion of the CO

2

production estimate can be improved

by taking more samples during this period. The bio-

logical half-life of a tracer is the time taken for the

isotope concentration to fall to half its original value.

In man, this may vary from 3 days for lactating

women in tropical countries to 14 days in elderly

Western subjects. Average values for the accuracy of

the method in comparison to CO

2

production meas-

urements made during whole-body calorimetry stud-

ies in man range from 8.7 to þ1.9%, and in routine

field use, the precision is better than 5%.

0024 So far, the method has been mainly used to try to

establish recommendations for energy intake of popu-

lations, to test the reliability of food intake measure-

ments, and to assess the significance of energy

expenditure in comparison to energy intake as causes

of obesity.

Heart Rate

0025 The responsiveness of heart rate to changes in activity

level has led to many attempts to relate heart rate

to energy expenditure and thereby to estimate free

living energy expenditure. Generally, this procedure

involves developing an individual relationship be-

tween a subject’s energy expenditure, measured under

laboratory conditions using indirect calorimetry, and

simultaneously measured heart rate. The energy

expenditure is modulated during this calibration

process by varying the subject’s activity from rest

on a bed, through sitting and standing, to cycle or

treadmill work over a range of intensities. The

energy expenditure increases little as heart rate is

increased by postural changes, but energy expend-

iture and heart rate both respond proportionally to

the increasing intensity of dynamic exercise. A var-

iety of techniques have been employed to describe

the relationship between energy expenditure and

heart rate. Many use a piece-wise linear approxima-

tion and attempt to define a point at which to make the

transition from a ‘rest’ line to an ‘exercise’ line. A more

elegant, though mathematically more complex, ap-

proach is to constrain a curve to fit the calibration

data taking lines through the resting and exercising

data as asymptotes.

0026The heart-rate method undoubtedly provides ex-

cellent qualitative information about energy expend-

iture and has been shown to be capable of predicting

the mean 24-h energy expenditure of eight subjects,

measured by whole body calorimetry, to better than

10%, though the accuracy of prediction for individ-

uals varies widely. It is only with the recent develop-

ment of the doubly labeled water technique that the

validity of the extrapolation from laboratory calibra-

tion to field energy expenditure can be effectively

tested, but heart-rate measurement is likely to remain

a useful technique for comparing the relative energy

expenditures of study groups when economics

preclude the use of doubly labeled water.

Activity Recording

0027Energy expenditure may be estimated from the records

in a diary of activities kept by the subject or an obser-

ver. The recordings are used to increment measure-

ments or predictions of resting energy expenditure to

provide energy expenditure estimates for each

recorded activity, which can be summed to give the

total energy expended over a period. As with heart

rate, the estimates yield good qualitative results suit-

able for comparing the relative expenditures of groups.

See also: Energy: Energy Expenditure and Energy

Balance; Meat: Analysis

Further Reading

Black AE, Coward WA, Cole TJ and Prentice AM (1996)

Human energy expenditure in affluent societies: an

analysis of 574 doubly-labeled water measurements.

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 50: 72–92.

Blaxter KL (1989) Energy Metabolism in Animals and

Man. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

0

−9.5

−9.3

−9.1

−8.9

−8.7

−8.5

−8.3

−8.1

−7.9

−7.7

−7.5

2468

Time post-dose (days)

Ln isotope concentration as fraction of dose (mole

−1

)

10 12 14 16

2

H

18

O

fig0002 Figure 2 Disappearance of

2

H and

2

O isotopes from the body

water pool in man.

2102 ENERGY/Measurement of Energy Expenditure

Cole TJ and Coward WA (1992) Precision and accuracy of

doubly labeled water energy expenditure by multipoint

and two-point methods. American Journal of Physiology

263: E965–E973.

Coward WA and Cole TJ (1991) The doubly labeled water

method for the measurement of energy expenditure in

humans: risks and benefits. In: Whitehead RG and Pren-

tice A (eds) New Techniques in Nutritional Research,

pp. 139–176. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Elia M and Livesey G (1992) Energy expenditure and fuel

selection on biological systems: the theory and practice

of calculations based on indirect calorimetry and tracer

methods. In: Simopoulos AP (ed.) Control of Eating,

Energy Expenditure and the Bioenergetics of Obesity,

pp. 68–131. Basel: Karger.

Kalkwarf HJ, Haas DJ, Belko AZ, Roach RC and Roe DA

(1989) Accuracy of heart-rate monitoring and activity

diaries for estimating energy expenditure. American

Journal of Clinical Nutrition 49: 37–43.

Kalkwarf HJ, Haas DJ, Belko AZ, Roach RC and Roe DA

(1998) Human energy balance: what have we learned

from the doubly labeled water method? American Jour-

nal of Clinical Nutrition 68: 409S–516S.

McLean JA and Tobin G (1987) Animal and Human Calor-

imetry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Murgatroyd PR, Shetty PS and Prentice AM (1993) Tech-

niques for the measurement of human energy expend-

iture: a practical guide. International Journal of Obesity

17: 549–568.

Prentice AM (1990) The Doubly-labeled Water Method for

Measuring Energy Expenditure. Vienna: International

Atomic Energy Agency.

Energy Expenditure and Energy

Balance

N G Norgan, Loughborough University, Loughborough,

Leicestershire, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 The origins of energy expenditure lie within the meta-

bolic activities of the body. To maintain an ordered

state, as opposed to randomness and chaos, requires

energy. To preserve the ionic gradients across cell

membranes, and to allow the activity of cells, tissues,

and organs as well as their control by enzymes, hor-

mones, and nerves, requires energy. To maintain res-

piration and circulation, to grow or produce new

tissue, to move and to work, all require energy. The

energy expenditure results from these activities and

functions. However, these are not amenable to indi-

vidual measurement in the free-ranging human being.

Using indirect calorimetry, it is possible to measure

the energy expenditure at various levels of exertion –

sleeping, lying, sitting, standing, walking, occupa-

tional and nonoccupational activities, and under

various influences, such as eating, hot and cold envir-

onments, disease, pregnancy, and lactation. From the

duration and energy cost, the total energy expend-

iture in each activity under specified conditions can

be determined and the total daily energy expenditure

(TDEE) calculated. An example is given in Table 1.

This is a lengthy and laborious procedure and there

are doubts about the precision and accuracy of the

method. The advent of a new technique based on

the disappearance of a dose of doubly labeled water

has enabled a measurement of TDEE with some

degree of confidence in most cases. Basal metabolism

can be measured with relative ease and precision, and

subtraction of the basal metabolism from TDEE gives

the energy expenditure resulting from physical activ-

ity and thermogenesis. Although this model of the

components of energy expenditure is less informative,

it is felt to be more precise and accurate and so better

for investigation of energy balance and imbalance.

0002Energy balance can be described by the energy

balance equation:

Energy intake ðEIÞenergy expenditureðEEÞ¼

change in energy stores ðDESÞ

tbl0001Table 1 Typical time use, energy cost of activity (physical

activity ratio: PAR), and energy expenditure in a group of young

male office workers of median body weight

Activity Time (h) PAR Energy

MJ kcal

In bed 8.00 1.0 2.44 580

Office work

Sitting 4.50 1.4 1.92 460

Standing 1.00 1.7 0.52 125

Sitting

Eating 0.75 1.2 0.27 65

Driving 1.00 1.4 0.43 100

Watching TV 3.75 1.2 1.37 325

Miscellaneous 1.50 1.3 0.59 140

Standing

Personal 1.00 2.0 0.61 145

Washing up 0.25 1.8 0.14 35

DIY 0.50 2.7 0.41 100

Car maintenance 0.50 2.7 0.41 100

Miscellaneous 0.50 2.1 0.32 75

Walking

Slow pace 0.25 2.8 0.21 50

Normal pace 0.50 3.7 0.56 135

Daily total 24.00 PAL ¼ 1.4 10.20 2435

PAR ¼ (energy expenditure of an activity)/(basal metabolic rate, BMR).

Physical activity level (PAL) ¼ (total daily energy expenditure)/(BMR).

ENERGY/Energy Expenditure and Energy Balance 2103

0003 Energy intakes in excess of energy expenditure will

result in increased body energy stores and, conversely,

when energy expenditure exceeds energy intake the

deficit is drawn from the energy stores. As we eat

intermittently but expend energy continuously, we

regularly alternate between positive energy balance

after meals and negative energy balance between or

before meals. Energy balance must then be expressed

over some time period, usually 24 h.

0004 Positive energy balance is the norm over much of

the life cycle as we grow and increase energy stores in

childhood and adolescence, in pregnancy, and during

adulthood. However, the extent of positive energy

balance is quite small in most of us. The energy de-

posited in growth in the newborn may be one-third of

the energy intake but by 6 months it is less than 5%.

The fat gain of 10 kg experienced by many between

the ages of 20 and 50 years requires only 0.001%

of the energy intake.

0005 The existence of energy balance, neither gaining

nor losing energy, fat, and weight, is not by itself a

sign of good energy nutritional status. The obese and

the undernourished are often in a static state of nei-

ther gaining nor losing energy. It is only during the

dynamic phase that the expected perturbations in

energy balance are manifest.

0006 The regulation of energy balance has been a subject

of some controversy. Do we eat to meet the require-

ments for energy expenditure and energy gain, or do

we modify expenditure according to the level of intake

in order to maintain appropriate energy stores and

energy gain? These are questions considered below.

Components of Total Daily Energy

Expenditure

Basal Metabolism, Activity, and Thermogenesis

0007 The basal metabolic rate (BMR) is defined as the

energy expenditure at complete bodily rest, in a ther-

moneutral environment, 12–18 h after the last meal.

These are conditions which rarely exist or persist in

ordinary daily life. They are most commonly met on

waking in the morning, when BMR is best measured.

BMR amounts to about 4.2 kJ (1 kcal) kg

1

body

weight h

1

in men and 3.8 kJ (0.9 kcal) kg

1

h

1

in

women, i.e., about 4.2 kJ min

1

. BMR is not the

lowest rate of energy expenditure of the day but its

ease of measurement, relative precision, and the size

of the existing database of information render it a

suitable index for study. The resting metabolic rate

(RMR) is measured with the less rigorous exclusion

of the effects of previous eating and physical activity

and is 3–5% higher than BMR. It shows a circadian

(daily) rhythm of amplitude 5–10% with a peak at

around 16.00–18.00 h and a trough in the early hours

of the morning. Many women show a 5% variation

over the menstrual cycle, being lowest 1 week before

ovulation and highest 1 week after ovulation.

0008The energy expenditure at rest is determined to a

large extent by the body weight and, in particular, by

the lean body mass (See Body Composition). Men

have higher resting energy expenditures than women

do. The difference persists when energy expenditure

is expressed per kg body weight because men tend to

be leaner and each kg has more lean tissue that is

more metabolically active than adipose (fat) tissue.

Metabolic rate tends to fall with age too as lean body

mass declines associated, in part, with a fall in level

of activity.

0009Size is an important determinant of the energy ex-

penditure in activities too, but to this must be added

the extent to which the body weight is moved, hori-

zontally and, in particular, vertically. The energy ex-

penditure of walking and running can be estimated

reliably from data on body weight, speed, incline, and

the nature of the surface, e.g., tarmac, soft sand. Not

surprisingly, walkers freely choose stride lengths and

step frequencies associated with the lowest net energy

cost of travel. Unfortunately, there are few other

groups of activities where energy costs can be sum-

marized by simple equations.

0010Comparisons of the energy expenditure of activities

can be made by the physical activity ratio (PAR), i.e.,

the energy expenditure of an activity divided by

BMR. This makes an approximate adjustment for

age, sex, body weight and, in some cases, body com-

position so that values are more easily comparable in

the different members of the population. The PAR of

sitting quietly is about 1.2; for standing it is 1.7, but

for walking at 5 km h

1

it is 3–4 and for walking at

5kmh

1

up a 25% incline it is 5 or more. The PARs

of some everyday activities are shown in Table 1.

These are values obtained during continuous activity

but in everyday life we usually interpose pauses and

breaks or a mixture of activities. If a task is hard, e.g.,

PAR 4–6, as in laboring and construction work, rest

pauses are essential if the activity is to be maintained

for any length of time. In the fraction of a second it

takes to jump upwards, the rate of energy expenditure

may be 25–50 times that at complete rest. However,

we are only able to maintain activities of PAR 4–5

over the whole of a working day by introducing more

rest and recovery pauses into the work pattern. (See

Exercise: Metabolic Requirements).

0011The third component of energy expenditure has

been called thermogenesis. This is an unfortunate

term as most of the energy expended (strictly speak-

ing, transduced) appears as heat anyway. Here,

thermogenesis refers to the extra heat production

2104 ENERGY/Energy Expenditure and Energy Balance

arising from energy expenditure associated with the

ingestion and metabolism of food and with the extra

heat required to maintain body temperature constant,

by shivering or other mechanisms, as opposed to the

waste heat which usually has this effect. Each of these

components of thermogenesis have been further sub-

divided, in the case of diet-induced thermogenesis

(DIT), into obligatory and facultative or adaptive

DIT, while cold-induced thermogenesis has been sub-

divided into shivering and nonshivering thermogen-

esis (NST).

0012 Obligatory DIT has several synonyms, e.g., thermic

effect of food, heat increment of food. It represents

the energy cost of digestion and absorption and the

handling of absorbed nutrients, particularly the cost

of synthesis. It is some 5–10% of dietary energy but

may be higher for single food constituents such as

protein. The thermic effect of food is normally in-

cluded in measurements of energy expenditure and

is not assessed separately. Facultative DIT and NST

have been examined closely as possible components

of energy expenditure that could be altered to allow

energy balance to be maintained on widely different

levels of energy intake. This is described more fully

below. Extremes of climates may affect energy ex-

penditure at rest and volitional physical activity. In

everyday life in temperate parts of the world, behav-

ioral and technological adjustments of and to clothing

and control of the built environment ameliorate these

climatic effects. Over the years, views about whether

BMR are lower in the tropics, in particular the South

Asia Indians, and raised in indigenous circumpolar

populations for their body size and composition have

tended to fluctuate more according to the zeal of the

investigators rather than the quantity and quality of

the evidence.

0013 The TDEE is less variable than the daily energy

intake. This is because whereas we may choose to

eat a little or a lot, we can never expend no energy,

and fatigue can reduce the extent to which we can

raise expenditure. With our modern, sedentary life-

styles, resting energy expenditure makes up 70% of

TDEE for most of us. Expressed in another way,

physical activity levels (PAL ¼ TDEE/BMR) for men

and women in light occupations with nonactive

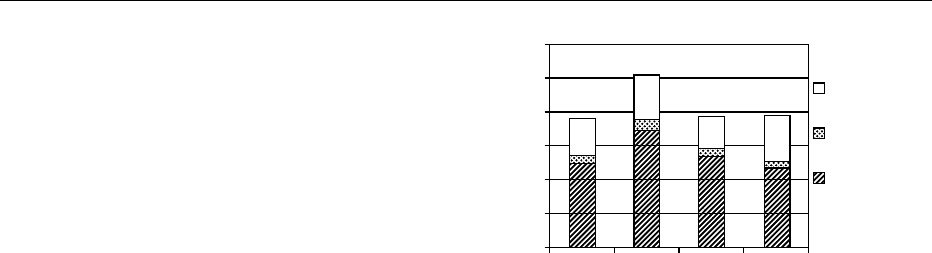

leisure time are 1.4–1.5 (Table 1 and Figure 1). Values

of up to 2.0 have been recorded in some occupations

and 2.5–3.5 in athletes in training and competition,

but to reach values of 4 it is necessary to work at the

level of Tour de France cyclists. In mammals and

birds, the maximum seems to be 7. The existence of

a ceiling is a consequence of the need for increased

mass of energy-supplying organs with high mainten-

ance and operating costs in very active species match-

ing the high levels of activity.

0014High TDEE may be achieved by occupations or

activities performed at a moderate level for many

hours a day or by a shorter period of intensive activ-

ity. The physiological characteristics necessary for

these two activity patterns are very different. Much

higher levels of fitness and work capacity are needed

for intense activity without excessive strain. Con-

versely, fitness improvement and health promotion

require activity above a threshold intensity. More

time at a lower level may not have the conditioning

effect sought. For most of the population, however,

exercise such as brisk walking may be of sufficient

intensity. Common exercise regimes of three to four

times per week for 30–60 min do not alter TDEE

significantly. The benefits of exercise lie elsewhere.

Variation and Trends in Energy

Expenditure

0015Individuals differ in their levels of energy expend-

iture. Much of this may be attributed to their size

and composition (the proportions of actively metab-

olizing lean tissue and the less metabolically active

adipose tissue). Men have higher rates than women

do because of both size and composition differences.

Different patterns of physical activity are the next

most likely or important origin of differences in

TDEE. Even with the same pattern of activity, indi-

viduals may select different rates, unless the activity is

paced, as in treadmill walking.

0016TDEE increases throughout childhood and adoles-

cence. In adulthood, TDEE declines where stable

body weight and falling levels of activity are found.

More commonly, increases in weight may balance

falls in activity such that TDEE may not alter much

Physical

activity

Themogenesis

Basal

metabolism

Grandmother

Father

Mother

kcal day

−1

Son

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

fig0001Figure 1 Total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) and its main

components in a family: the grandmother is 70 years and weighs

65 kg, the father is 40 years and weighs 75 kg, the mother is 40

years and weighs 62 kg and the 10-year-old son weighs 30 kg. The

physical activity levels (TDEE/basal metabolic rate) are 1.52,

1.47, 1.44, and 1.66 respectively.

ENERGY/Energy Expenditure and Energy Balance 2105

between 25–45 years. Thereafter, less child care and

career progression, leading to desk-bound work and

retirement, may further curtail activity. In addition,

BMR falls 2% per decade as lean tissue mass de-

creases. In very old age, incapacity restricts the ability

to be active and PAL levels may be only 1.2. Ill health

at other parts of the life cycle may also affect activity

and TDEE. In many parts of the world, infection not

only causes personal misery but also seriously affects

subsistence and occupational activity. Pregnancy has

the twin characteristics of an increasing body size plus

a customary fall in activity, particularly in the last

trimester. Therefore the total extra cost of pregnancy

may be less than expected, unless the woman does not

reduce activity.

0017 The contribution of genetic factors to differences in

energy expenditure is very difficult to investigate and

whether any genetic differences are actually ex-

pressed in the individual or population depends on a

multitude of factors. Results from twin and other

studies suggest that variations in RMR, thermic effect

of food, level of physical activity, and energy cost of

light exercise have a low to moderate genetic com-

ponent. There are frequent reports in the literature of

low BMR in tropical populations, particularly from

the Indian subcontinent. Whether these arise from

differences in size and composition and nutritional

status, or ethnic differences per se, is controversial.

Some groups have a renowned propensity for fatness,

and a hypothesis of a thrifty genotype has been put

forward to explain massive overweight and obesity

in, for example, Polynesians and the Pima Indians

of Arizona, USA, apparently as they altered their

traditional lifestyle and took up western habits. The

hypothesis suggests that, in response to chronic food

shortages over many generations, individuals with

more efficient energy utilization survived and bred

selectively. Now that high energy intake can be

achieved with low energy expenditure, the superior

efficiency results in high energy stores. To support the

hypothesis, evidence of a lower energy turnover or

increased efficiency is required. In Pima Indians some

families do have lower RMR than others and these

show higher rates of obesity. But, a major problem in

human energetics is how to compare the rates of

energy expenditure in individuals of different sizes,

whether the small, thin individuals in India with ap-

parently low BMR or these large, obese individuals,

where low BMR is also being sought. The problem is

less difficult for physical activity as the net mechan-

ical efficiency (NME ¼ work done divided by energy

expended) is an appropriate index of efficiency. Al-

though NME varies between individuals for reasons

that are not entirely clear, there is no consistent pat-

tern of evidence suggesting that the body can alter

NME in response to varying planes of nutrition in the

short term or over many generations. This attractive

hypothesis of a thrifty genotype spread throughout

the population appears evolutionarily sound but

remains a hypothesis.

0018Owing to the pervasiveness of modern communi-

cation, all societies and populations experienced

changes in lifestyle in the 20th century. For many this

has meant a shift from subsistence lifestyles, where all

material needs were met by 2–3days’ work per week,

to long hours of repetitive, often hard, poorly paid

labor. In the developed economies, the trend has con-

tinued towards increased mechanization, a fall in the

length of the working week, and increased holiday

entitlements, which have reduced the effort in work,

particularly the peak- and high-intensity efforts. The

effect of this on TDEE is difficult to gauge. Surpris-

ingly, analyses suggest there are no differences in levels

of habitual physical activity, as evidenced by PALs,

between the developed and the developing world.

This might be explained, in part, by the curtailment

of physical activity as a behavioral adaptation to the

presence of chronic energy deficiency. It does high-

light, however, the pitfalls of taking as self-evident

beliefs about energy expenditure and physical activity.

There have been few representative national studies of

current-day activity and expenditure patterns, let

alone studies for earlier periods of the last century.

One way round this is to ignore the small effect of

the greater energy stores in modern populations and to

assume that energy intakes reflect energy expenditure.

Again, there are no national representative intake data

from earlier years but the evidence suggests that levels

of energy expenditure have fallen, albeit only in the

last 10–20 years.

Control of Energy Expenditure and

Regulation of Energy Balance

0019There are several types of factors operating at differ-

ent levels. At the primary level, the setting of regula-

tory centers in the brain or mechanisms at the cellular

level may ultimately determine the level of energy

balance. These respond to changes in energy intake

and expenditure, at a secondary physiological, bio-

chemical, or neurophysiological level. Traditionally,

the regulation of energy balance has been seen as

energy intake being controlled to match antecedent

levels of energy expenditure. It has been argued

recently that regulation of energy balance is less ac-

curate when the energy intake is high in fat, as char-

acterizes many contemporary diets, than for diets

with low-fat energy and that this contributes to the

modern rise in the prevalence of obesity. In contrast,

attention has also been paid to the possibility of the

2106 ENERGY/Energy Expenditure and Energy Balance