Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

equivocal evidence suggests a potential role for vita-

mins A, C, E, and niacin and the minerals chromium

and vanadium in diabetes. Alternative sweeteners,

e.g., sorbitol and saccharin, are accepted in diabetes

management but their value is unclear. The control of

hyperglycemia by diet and medication is associated

with reduced risk of some of the long-term compli-

cations of diabetes.

Obesity

0025 The determination of obesity in the elderly is prob-

lematic since few body weight standards specific to

this age group are in use. The prevalence of obesity

appears to increase with age. Weight gain normally

occurs during the adolescent growth spurt and again

during middle age. Basal metabolic rate and energy

expended for physical activity decline during adult-

hood so that fewer calories are required to maintain

energy balance; however, many middle-aged and

older adults often do not adjust their caloric intake

to compensate for their reduced energy requirements

and gain weight even though they do not eat more

than before. Body weight generally peaks between 35

and 55 years in men and between 55 and 65 years in

women; body weight decreases thereafter in both

sexes. Obesity aggravates many health conditions

found among the elderly including arthritis, cardio-

vascular diseases and hypertension, and type 2

diabetes.

Osteoporosis

0026 Primary osteoporosis is an age-related disorder char-

acterized by decreased bone mass and increased

susceptibility to fractures in the absence of other

recognizable causes of bone loss. Postmenopausal

osteoporosis (type 1) occurs in women within 15–20

years after menopause and is thought to result from

factors related to or exacerbated by estrogen defi-

ciency. Age-related osteoporosis (type 2) occurs in

men and women over 75 years of age and may be

more directly related to the aging process. Whites are

at higher risk of osteoporosis than blacks. Other risk

factors include dietary factors, cigarette smoking,

physical inactivity, alcohol abuse, being underweight,

and family history of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is

more than six times as common among women than

men due to their smaller peak bone mass, earlier

onset of bone loss, longer life expectancy, and lower

calcium intake.

0027 Substantial evidence supports a role for calcium as

a protective agent against osteoporosis. High calcium

intake during early years contributes to greater peak

bone mass and during later years prevents negative

calcium balance and reduces the rate of bone loss.

Poor calcium nutriture is common among the elderly

due to inadequate intake, an age-related decline in the

capacity for calcium absorption, and the presence of

diseases associated with reduced calcium absorption

and/or increased calcium excretion. Vitamin D is

essential for the efficient absorption of calcium but

vitamin D status is quite low among the elderly due to

inadequate intake and age-related impairments in the

metabolic conversion of vitamin D to its biologically

active form, including lower precursor concentra-

tions of 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin. Less

well-established dietary risk factors for osteoporosis

include low intakes of vitamin K or boron and high

consumption levels of caffeine, protein, or alcohol.

The principal measures employed in the prevention

of osteoporosis include estrogen replacement in

postmenopausal women, elemental calcium intakes

of 1000–1500 mg day

1

, vitamin D intakes of

10–20 mg cholecalciferol day

1

, and a program of

modest weight-bearing exercise. These measures may

retard further bone loss in the elderly but will not

restore lost bone or reverse the loss in height or col-

lapsed vertebrae characteristic of osteoporosis.

See also: Anemia (Anaemia): Other Nutritional Causes;

Anorexia Nervosa; Cancer: Epidemiology; Diet in

Cancer Prevention; Coronary Heart Disease: Etiology

and Risk Factor; Prevention; Dehydration; Dietary Fiber:

Effects of Fiber on Absorption; Lipoproteins; Obesity:

Etiology and Diagnosis; Epidemiology; Osteoporosis

Further Reading

Bendich A and Deckelbaum R (1997) Preventive Nutrition,

The Comprehensive Guide for Health Professionals.

Totowa, NJ: Humana Press.

Chernoff R (1999) Geriatric Nutrition. Rockville, MD:

Aspen.

Graham I, Refsum H, Rosenberg IH and Ueland PM (1997)

Homocysteine Metabolism: From Basic Science to

Clinical Medicine. Boston: Kluwer Academic.

Harman D, Holliday R and Meydani M (1998) Towards

Prolongation of the Healthy Life Span. New York, NY:

New York Academy of Sciences.

Holliday R (1995) Understanding Ageing. New York, NY:

Cambridge University Press.

Rosenberg IH (1995) Nutritional Assessment of Elderly

Populations: Measure and Function. New York, NY:

Raven Press.

Rowe JW and Kahn RL (1998) Successful Aging. New

York: Pantheon Books.

Schneider EL and Rowe JW (1996) Handbook of the Biol-

ogy of Aging. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Sies H (1997) Antioxidants in Disease Mechanisms and

Therapy. San Diego: CA: Academic Press.

Taylor A (1999) Nutritional and Environmental Influences

on the Eye. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

ELDERLY/Nutritionally Related Problems 2027

Nutritional Management of

Geriatric Patients

M S J Pathy, Cyncoed, Cardiff, UK

A Bayer, Llandough Hospital, Penarth, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 At all ages, adequate nutrition is critical for maintain-

ing health and quality of life. In general, dietary pro-

tein and energy requirements are substantially less in

the over 85s than those aged 65–74 years, and there is

an increased need for certain vitamins and minerals.

However, individual requirements are influenced

greatly by lifestyle and by disease. Maintenance of

physical fitness and strength in old age largely

depends on continued physical and mental activity,

with enough to eat and a diet that is sufficiently

varied. Elderly people in low socio-economic groups,

those in institutions, and the housebound who are

receiving home care are especially vulnerable to

undernutrition, through underprovision and inad-

equate intake. Drugs and disease may also interact

with the complex metabolic processes necessary for

breaking down and absorption of food. Increasingly,

calorie overconsumption is a problem in Western

society, with 25% of men and 35% of women in the

65–74 age range being reported as overweight and

10% being severely overweight.

0002 In the UK, the Committee on the Medical Aspects

of Food and Nutrition Policy (COMA) laid down

general guidelines for dietary requirements of older

people together with modifications in disease states.

Table 1 summarizes the dietary reference values

(DRVs), which replace the earlier recommended diet-

ary allowances (RDA). The reference nutrient intake

(RNI) represents the sum of the estimated average

requirement (EAR) and two standard deviations.

Energy

0003 A reduction in physical activity and lean body mass in

old age lead to a decline in energy requirements by

about one-third. However, there is no reduction in

basal metabolic rate relative to the metabolically

active cell mass. Infection, trauma (accidental or sur-

gical), and the ergonomic impact of disability on daily

living tasks all serve to increase energy demands.

Dyspnea at rest or exertion (commonly seen in pa-

tients with chronic pulmonary obstructive airways

disease) and impaired immunological response to

infection also require increased energy intake as part

of therapeutic management.

0004COMA recommends that 50% of food energy is

derived from carbohydrate – a term that embraces

starch and nonstarch polysaccharides. The main

source of starch is influenced by ethnicity and culture,

with bread, potatoes, breakfast cereals, rice, and

pasta predominant in the UK. Distinction is made

between intrinsic sugars (milk sugar, and sugar in-

corporated in the cellular structure of fruit and vege-

tables) and extrinsic nonmilk sugars (extracted from

the fruit stem and roots of plants and added to food,

confectionery, and soft drinks). A high extrinsic sugar

intake may reduce the dietary quality and in the den-

tate increases the risk of caries.

0005Different carbohydrates have different glycemic

indexes (Table 2). This is the area of the blood sugar

curve produced by a food, compared with the equiva-

lent amount of glucose. Glucose has an arbitrary

glycaemic index of 100. Previously, white bread was

taken as the standard. Excess high glycemic index

carbohydrates are associated with a low high-

density-lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol concentration,

tbl0001Table 1 Dietary reference values for older men and women

(based on COMA recommendations)

Nutrition Sex/age (years) Estimated

average

requirements

(EAR)

Reference nutrient

intake (RNI)

Energy

a

M 65–74 9.71 MJ

M75þ 8.77 MJ

F 65–74 7.96 MJ

F75þ 7.61 MJ

Protein M 50þ 53.3 g

F50þ 46.5 g

Vitamin A M 700 mg

F 600 mg

Vitamin D M/F 10 mg

Vitamin C M/F 40 mg

Thiamin M 1.0 mg

F 0.8 mg

Riboflavin M 1.3 mg

F 1.1 mg

Niacin M 16 mg

F12mg

Vitamin B

12

M/F No recommendation

Vitamin E M/F No recommendation

Phosphorus M/F 500 mg

Magnesium M 300 mg

F 270 mg

Iron M/F 8.7 mg

Potassium M/F 350 mg

Zinc M/F 9 mg

Copper M/F 1.2 mg

Sodium M/F 6 g

Fluid M/F 1.5 l

a

No RNI for fat/carbohydrates (expressed as EAR due to the close

correlation between energy requirement and expenditure).

M, male; F, female.

2028 ELDERLY/Nutritional Management of Geriatric Patients

rapid absorption, and a high postprandial glucose

and insulin response, ultimately giving rise to

decreased insulin sensitivity. Total cholesterol and

low-density-lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol are not in-

fluenced. One community study has confirmed that

low-glycemic-index diets are associated with raised

HDL cholesterol levels and the longitudinal Nurse

Health Study reports that diets with a high glycemic

index are associated with an increased risk of coron-

ary heart disease (CHD). Increasing prominence is

being given to the role of high-glycemic diets and

the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

0006 Fat is the most concentrated calorie nutrient. In

the USA, it is recommended that 30% or less of

calories should be derived from fat, of which no

more than 10% should be saturated. The UK Health

of the Nation aims to reduce average percentages of

food energy derived from fat by at least 12% by

2003 and that derived from saturated fat by 35%

by 2005. The chief source of saturated fat is meat,

butter, cheese, and cream. Unsaturated fats are de-

rived mainly from plant sources, especially nuts,

olive oil, rapeseed oil, some margarines, and fish.

Evidence supports the role of saturated fats and

trans-fats (hydrogenated polyunsaturates) in athero-

matous vascular disease, although infection may be

the initial trigger. COMA recommended a reduction

of saturated fat and total fat contribution to the diet.

However, there is no correlation between polyunsat-

urated fat intake and LDL levels. Indeed, the unsat-

urated fat in fish and in olive oil – about 70%

monounsaturated – enhances the plasma concentra-

tion of the vascular-protective HDL cholesterol. The

Nurse Health Study showed that women taking at

least one ounce (15 g) of nuts five times or more a

week had a greater reduction in risk of CHD than

those who took them less frequently. Experimental

diets replacing animal fats with nuts lowered LDL

cholesterol and raised HDL cholesterol. Walnuts are

high in linoleic acids, but most nuts are rich in argin-

ine, a precursor of nitric oxide. A major longitudinal

study showed that an increase in polyunsaturated fat

intake accompanied by a reduced consumption of

trans-fats diminishes the risk of type 2 diabetes mel-

litus. Studies based on Mediterranean diets (charac-

terized by abundant fruit and vegetables, especially

garlic and onions, cereals, beans, nuts, seeds, olive

oil, fish and poultry) have reported a reduced risk of

CHD and cancer.

0007Although a reduction in total dietary fat has no

affect in reducing blood pressure, increasing the diet-

ary polyunsaturated : saturated ratio or changing to

diets rich in linoleic acids produces a moderate blood-

pressure reduction. However, one study reported that

attempts to enhance compliance with dietary recom-

mendations in the over-70s was only half as successful

as in the 60–69-year age group.

Protein

0008By age 70, skeletal muscle may have lost an average of

40% of its cell mass. Protein synthesis decreases as

body cell mass falls with age and is associated with a

decline in function. Functional decline is not irrevers-

ible and maintenance of physical activity or physical

training may increase muscle strength and cardiac

output. Protein malnutrition is associated often with

profound muscle loss and weakness, and impaired

immunological competence. However, this stage is

usually compounded by other nutritional deficiencies

and by serious disease.

0009Debate continues about protein requirements in

old age. Studies on free-living and institutionalized

older people suggest that the daily protein require-

ment should be about 1.0 g kg

1

and about 12–14%

total calories. Inflammatory conditions and tissue

necrosis (e.g., pressure sores) increase the protein

turnover and requirement, and pressure-sore healing

rates are influenced greatly by dietary protein intake.

Protein malnutrition may follow major surgery or

severe acute illness in elderly people and can seriously

impair subsequent rehabilitation if left untreated.

Vitamins and Minerals

0010Vitamin and mineral supplements are necessary to

treat well-defined deficiency disorders, but their role

is less certain in the absence of obvious clinical

tbl0002 Table 2 Glycemic index of selected foods (mean values)

Food Glycemic index

Glucose 100

Instant rice 91

Baked potato 85

Cornflakes 84

White bread 70

Wholemeal bread 69

Sucrose (table sugar) 65

White rice (basmati) 58

Boiled potato 56

Banana 55

Baked beans (canned) 48

Orange 43

Pasta (spaghetti) 41

Apple 36

Milk 27

Kidney beans 27

Fructose 23

Derived from 600 entries in Foster-Powell K and Miller J (1995)

International Table of Glycemic Index. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

62: 8715–8935.

ELDERLY/Nutritional Management of Geriatric Patients 2029

abnormality. Many older people fail to make the

reference values for vitamin D, but the synthesis of

vitamin D

3

(cholecalciferol) by the action of sunlight

(UVL with a wavelength of 290–310 nnm) on the skin

contributes some two-thirds of the vitamin D stores.

Standard household glass prevents the passage of any

therapeutic wavelength of UVL, and housebound and

institutionalized patients are particularly susceptible

to vitamin D deficiency. Subtle degrees of vitamin D

deficiency lead to secondary hypoparathyroidism, in-

creased bone turnover and osteoporotic fractures.

Common dietary sources of vitamin D include eggs,

cheese, margarine (fortified with vitamins D and A),

and oily fish. Randomized controlled trials of dietary

supplementation with 17.5 mg (700 IU) and 20 mg

(800 IU) of vitamin D and 500 mg of calcium per

day show a reduced incidence of hip and other

nonvertebral fractures, whereas 10 mg (400 IU) of

vitamin D does not reduce the fracture rate. There is

considerable evidence for using vitamin D and cal-

cium supplements in the vulnerable elderly, provided

overdosage is avoided. Exposure to sunlight, even

diffuse sunlight, is also to be encouraged.

0011 Water-soluble vitamin C is readily destroyed during

food preparation and storage, and the COMA recom-

mendation of 40 mg does not take this into account.

The delay between preparation and delivery to the

patient in hospital or nursing home or of meals on

wheels to the person at home is often sufficient

to substantially reduce the vitamin C content. Meals

on wheels are reported to have lost some 90% of the

vitamin C content by the time of delivery. Older

people eat vegetables more regularly than young

adults, but elderly men who live alone have diets

poor in vitamin C-rich foods such as fresh green vege-

tables and fruit. Scurvy is uncommon, but chronic

mild deficiency is not infrequent and may play a role

in atherogenesis and stroke. The inverse correlation

between plasma fibrinogen concentration and serum

ascorbate levels suggests that vitamin C supplemen-

tation may be cardioprotective.

0012 Vitamin A intake is very variable, but needs tend to

decrease with age, as absorption may be increased,

whilst plasma clearance is delayed. However, it is

often difficult to be certain whether homeostasis is

achieved, or whether subclinical vitamin A states are

common and unrecognized. Failure of dark adapta-

tion is a well-recognized vitamin A deficiency phe-

nomenon, but dryness of the eyes and perifollicular

hyperkeratosis are uncommon deficiency manifest-

ations in the Western World. In some third world

countries, vitamin A deficiency is the commonest

cause of blindness. The potential benefit of the anti-

oxidant properties of vitamin A and the closely related

b-carotene have yet to be established.

0013Thiamin (vitamin B

1

) intake is closely related to

energy consumption. Older people generally eat

breakfast (‘something to eat within 2 hours of rising’),

and this commonly includes cereals and fortified

cereals containing adequate thiamin. If disease or

institutionalization impairs energy consumption,

thiamin intake may be deficient. Alcoholism may

give rise to confabulation and short-term memory

impairment (Korsakoff’s psychosis) due to associated

thiamine deficiency or, more rarely, Wernicke’s

encephalopathy – acute confusion, ataxia, and

opthalmoplegia. Acute postoperative delirium is not

improved by large parenteral doses of the vitamin B

group of vitamins. Any associated low plasma thia-

mine concentration may be an epiphenomenon.

0014Pyridoxine (vitamin B

6

) and folate are important

cofactors for the metabolism of homocysteine, and

both vitamins independently lower raised homocys-

teine levels, thought to play a key role in atherogen-

esis. The Nurse Health Study found that a long-term

intake of 3 mg of vitamin B

6

and/or at least 400 mgof

folate per day have a favorable impact on CHD. In

the Framingham Study, 20% of elderly subjects had

folate and vitamin B

6

levels below the recommended

intake.

0015Folic acid in its conjugated form (predominantly

polyglutamate) is present in a wide variety of food,

especially green leafy vegetables, kidney, and liver.

Hydrolysis of the polyglutamate to monoglutamates

is necessary for absorption in the small intestine.

Folate deficiency may be due to several causes, with

inadequate intake the most common, often aggra-

vated by prolonged cooking, which destroys the

vitamin. Disease that impairs absorption (e.g., gluten

enteropathy or ileal resection) or increases metabolic

demand (e.g., vitamin B

12

deficiency, the leukemias,

myelofibrosis, hemolytic anemia, sideroblastic ane-

mia) may result in deficiency. A number of drugs (e.g.,

trimethoprim, methotrexate, triamterene) inhibit con-

version of folate to tetrahydrofolate, which is the main

storage and metabolically active form of the vitamin.

The anticonvulsants, phenytoin, primidone, and

phenobarbitone, and the antibiotic, nitrofurantoin,

may also result in folate deficiency, but the underlying

mechanism has not been firmly established. Defective

DNA synthesis through the purine and pyrimidine

pathways following chronic dietary folic acid defi-

ciency or drug-induced activity gives rise to a megalo-

blastic anemia. Provided that vitamin B

12

deficiency is

not present, treatment with as little as 200 mg daily of

oral folic acid is rapidly effective. In practice, pharma-

cological doses of 1–5 mg daily are used. Folinic acid

(Leukovorin), a form of tetrahydrofolate, is preferable

if the deficiency is due to folate antagonist drugs. The

COMA recommendation of 200 mg per day isadequate

2030 ELDERLY/Nutritional Management of Geriatric Patients

forred cell formationbut may notbeoptimal forhomo-

cysteine metabolism and vascular wall integrity.

0016 Dietary deficiency vitamin of B

12

is rare, except

in strict vegans. This is predominantly due to the

efficient recirculation of the vitamin and a reported

half-life of 480–1360 days. The predominant cause

vitamin B

12

deficiency is loss of intrinsic factor pro-

duction by the gastric parietal cells, most often due to

autoimmune disease giving rise to pernicious anemia.

Antibodies against parietal cells and less commonly

against intrinsic factor may be found in the gastric

juice or serum. The inability to separate vitamin B

12

from its dietary binding protein may also cause vita-

min B

12

deficiency; lack of gastric acid and pepsin

contribute, but an unequivocal explanation has yet to

be established. Bacterial overgrowth as in blind loop

syndrome competes for available vitamin B

12

and

reduces the amount available from absorption. Gas-

tric surgery by removing some or all intrinsic factor

producing cells leads eventually to a low serum

vitamin B

12

concentration.

0017 Because the liver stores large amounts of vitamin

B

12

, evidence of deficiency does not occur for about 5

years, even after total gastrectomy. Ileal disease or

surgery often gives rise to vitamin B

12

deficiency.

The gradual but progressive development of anemia

and the well-hemoglobinized red cells often results in

minimal symptoms until an advanced anemic state.

The common symptoms of anemia – fatigue, breath-

lessness, and poor exercise tolerance, occur. Acute

onset of heart failure and angina is not uncommon

because of associated CHD and responds well to

vitamin B

12

treatment. Much has been written on

the relationship of dementia to vitamin B

12

defi-

ciency. Although low serum vitamin B

12

concentra-

tions are not uncommon in demented elderly patients

living in the community, there is little evidence of any

improvement in cognitive function following B

12

dosage. When some improvement does occur, it can

better be ascribed to concurrent treatment of other

comorbid states and correction of impaired total diet-

ary intake and improvement of restricted functional

and social activities. However, some neuropsychiatric

states are improved by vitamin B

12

therapy. Neuro-

logical symptoms are relatively rare. Symmetrical

peripheral neuropathy usually involving the lower

limbs is associated with paraesthetic symptoms and

evidence of ataxia and posterior column involvement

leading to lower-limb weakness and spasticity.

0018 Reduced plasma vitamin B

12

concentration is an

early feature of deficiency, though initially, the blood

picture may be normal. Later, macrocytosis and

megaloblastic bone marrow changes are character-

istic, with low white blood counts and multisegmen-

ted polymorphs. When diagnosis is equivocal, the

Schilling test is justified. In the presence of anemia, it

is useful to measure the reticulocyte response to vita-

min B

12

administration, which reaches its peak on

the 4th or 5th day. Treatment of confirmed deficiency

with 1000 mcg of intramuscular vitamin B

12

daily for

2 weeks rapidly replenishes body stores. Subsequently,

lifetime intramuscular injections every 3 months is

a cost-effective treatment schedule. Absorption of

1–3% of an oral dose of 1 mg of vitamin B

12

daily

generally satisfies the daily requirement of 2–5 mg.

0019The latest recommended vitamin E requirement is

15 mg per day. Vitamin E deficiency may result from

fat malabsorption or defects in the gene for the

a-tocopherol transfer protein and may give rise to

the insidious onset of peripheral neuropathy. A

possible influence of vitamin E (and vitamin C and

b-carotene) on excess free radical formation has led

the media to speculate on an antiageing effect. Al-

though no benefit has been seen in patients with

Parkinson’s disease, a placebo-controlled trial of vita-

min E 2000 IU daily in people with Alzheimer’s

disease has suggested a possible slowing of the rate

of disease progression. The antiadhesive effect of

vitamin E combined with the platelet antiaggregatory

effect of aspirin increases the risk of bleeding, and

caution is appropriate with supplementary vitamin E

in a dose greater than 500 IU per day.

0020Insufficient iron intake is mainly found in house-

bound and institutionalized older people. Meat and

cereals are the major sources of iron in the diet; fruit

and vegetables have much lower proportions. Some

flour and cereals are fortified with additional iron.

Vitamin C enhances, and phytates or tannins in tea

interfere with, iron absorption. Early iron store

reduction is demonstrated by low serum ferritin

concentrations. As iron deficiency progresses, anemia

may develop. Moderate to severe iron-deficiency

anemia is mostly due to chronic gastrointestinal

bleeding due to drugs (e.g., aspirin, anticoagulants,

nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs) or disease.

Symptoms of iron deficiency may follow the onset

of anemia and include fatigue, shortness of breath

or exacerbation of concomitant ischemic arterial dis-

ease, e.g., angina, congestive heart failure, and inter-

mittent claudication. Treatment of iron deficiency is

usually with ferrous sulfate, 200 mg two to three

times daily until the hemoglobin and iron stores are

replaced. Concomitant administration of ascorbic

acid as fruit juice or as a 50-mg vitamin C tablet

increases absorption and reduces gastrointestinal

side-effects. In the presence of a malabsorption

state, iron may have to be given parenterally, but the

potential risk of anaphylactic response requires super-

vision. Dietary advice on foods rich in available iron

is an essential part of the long-term strategy, but for

ELDERLY/Nutritional Management of Geriatric Patients 2031

some elderly people, a small dose of oral iron may be

a permanent requirement.

Dietary Fiber

0021 Dietary fiber keeps bowel movements regular and

prevents constipation when taken with a good fluid

intake and adequate exercise. Long-term intake of

dietary fiber decreases the risk of CHD and diverticu-

lar disease and helps management of diabetes mellitus

and hyperlipidemia. Its role in the prevention of col-

orectal cancer is still under debate. Only a minority of

older people consume the recommended daily intake

of 25–35 g of dietary fiber. This may be achieved

by eating more fruit and vegetables (preferably

unpeeled) by substituting whole-grain breads and

cereals for white bread and sugary cereals and adding

wheat bran and beans to soups, stews, and other

dishes. Excess fiber intake should be avoided, as it

may impair the absorption of trace minerals.

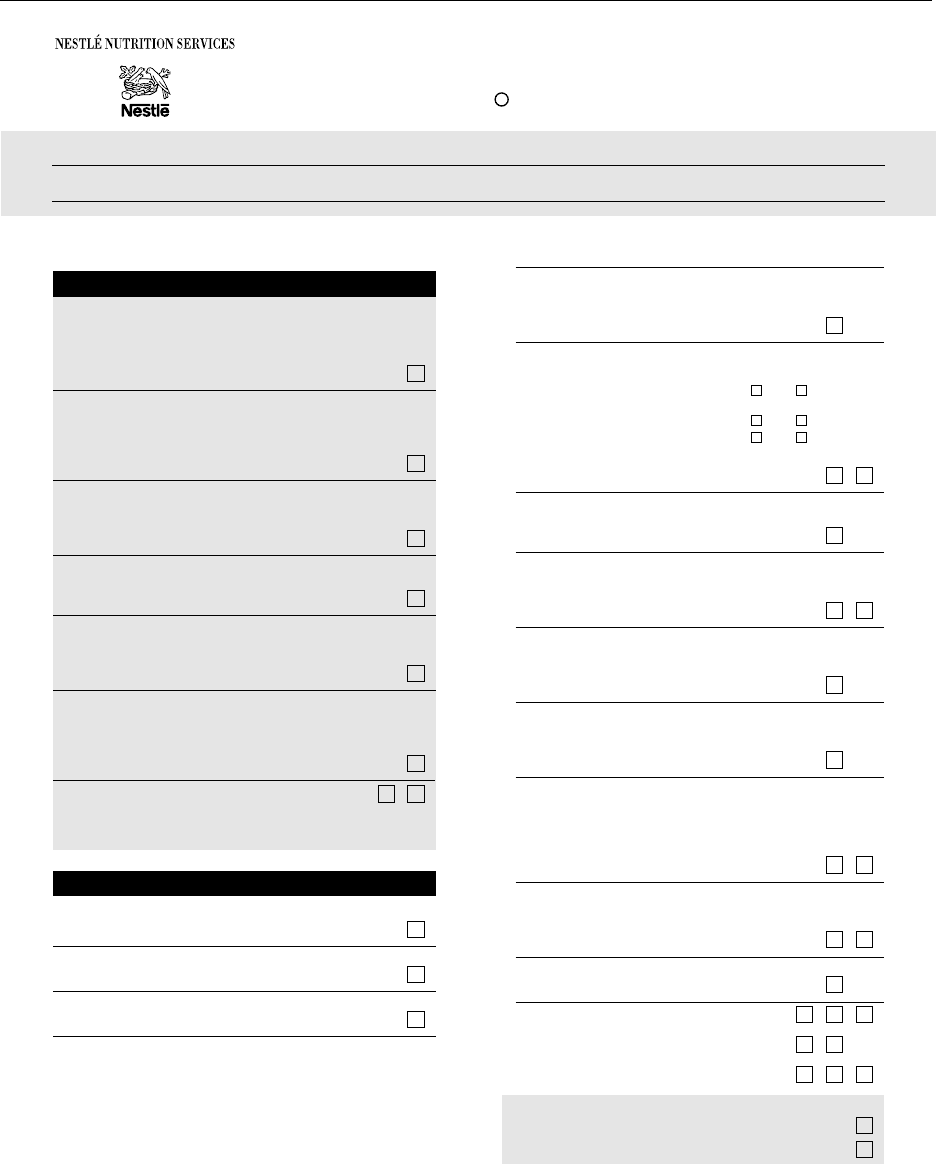

Clinical Evaluation

0022 Once clinical symptoms and signs appear, nutritional

impairment is firmly established. The Mini Nutri-

tional Assessment (MNA; Figure 1) can be under-

taken in 15 min and has been used successfully in

free-living older people, in residents of nursing

homes, and in hospital inpatients. A Danish 5-year

longitudinal study showed an increased mortality in

subjects with an MNA score of less than 23.5. Sub-

jects in a New Mexico Study with a high MNA score

of 27 or greater were classified as having very good

health.

0023 Weight is the traditional simple measure of nutri-

tional state and often goes unrecorded in medical and

nursing-home case notes. The body mass index (BMI)

(weight in kilograms/height, in meters, squared) is not

always feasible in disabled and bed-bound persons,

but the height can be calculated using the sitting knee

height (knee to floor or heel) or the demispan (sternal

notch to finger web in the outstretched arm). People

aged over 65 years are recommended to have a BMI

between 24 and 29. A BMI under 20 indicates under-

nutrition. Mortality rates increase in the very elderly

with low BMIs (under 20).

0024 Body fat distribution changes with age, and in both

sexes there is an increase in abdominal fat distribu-

tion and an increase of omental fat. In women, a

waist/hip ratio over 0.9 is associated with a threefold

risk of CHD when compared with a ratio of less than

0.7. Waist circumference is an independent risk

factor, and women with a waist circumference of

greater than 97 cm (38 inches) have a threefold risk

of CHD. Men with a waist circumference of greater

than 100 cm (40 inches) have a 2.5- to 4.5-fold

increase in one or more cardiovascular risks. Gall

bladder disease, cancer, and osteoarthritis are more

common in the overweight, and obesity, particularly

abdominal obesity, is a significant independent risk

factor for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

0025In older underweight persons, the cornerstone of

management is to identify and treat aggressively the

cause of weight loss. Poor appetite may improve with

treatment of depression or review of drugs, such

as digoxin, dopaminergic agents, and anticholines-

terases. Treatment of poor oral hygiene, swallowing

disorders, or malabsorption syndromes will increase

food intake and absorption. Good management of

systemic diseases such as cancer, chronic organ fail-

ure, infection, and inflammatory disorders, and rele-

vant metabolic diseases such as hyperthyroidism, all

require attention to the nutritional state. Attention to

social and economic factors and to countering phys-

ical disabilities may also be necessary. Highly restrict-

ive ‘medically indicated’ diets, for example, for

lowering cholesterol or managing diabetes, may also

lead to unintentional weight loss and nutritional

deficiencies, and a more relaxed, well-balanced, and

varied diet is likely to be preferable.

0026Intentional weight loss in obese older people may be

associated with functional and health benefits, though

some studies indicate that being overweight later in

life does not pose a significant health risk. Weight

reduction is a partnership between patient and med-

ical advisors. Without this approach, it is difficult to

maintain motivation and trust on the part of the pa-

tient. Randomized controlled studies firmly establish

that low-fat diets produce weight loss. A slowly pro-

gressive increase in exercise levels has only a small

impact on weight but has a more substantial benefit

on function and improves insulin sensitivity.

Nutritional Management in Specific

Medical Conditions

0027Pain and discomfort from inflammation of the gums,

mouth, or tongue and missing or illfitting dentures

will hinder adequate chewing and decrease food

intake. Preventive dental care (from an early age) is

the best management, and maintaining active dental

health policies is especially important for those in

institutions. When maintaining adequate nutrition

becomes a problem, high-protein–energy liquids and

soft nonacidic foods may be best tolerated, and a mild

topical local anesthetic mouthwash before meals may

help to relieve pain. Inadequate saliva production

arising from infection, anticholinergic drugs, radi-

ation therapy, or Sjogren’s syndrome will interfere

with taste and swallowing and may be partially

2032 ELDERLY/Nutritional Management of Geriatric Patients

relieved by spraying the mouth with artificial saliva

solution. Normal age-related changes in taste result in

older people being more sensitive to bitter and sour

flavors and less sensitive to sweet and salt. A declining

sense of smell means that food aromas that stimulate

the appetite must be several times stronger than usual.

0028Problems with swallowing (dysphagia) may be due

to inflammatory, traumatic (e.g., postintubation),

Complete the screen by filling in the boxes with the appropriate numbers.

Add the numbers for the screen. If score is 11 or less, continue with the assessment to gain a Malnutrition Indicator Score.

A Has food intake declined over the past 3 months due to loss of appetite,

digestive problems, chewing or swallowing difficulties?

0 = severe loss of appetite

1 = moderate loss of appetite

2 = no loss of appetite

B Weight loss during the last 3 months

0 = weight loss greater than 3 kg (6.6 lbs)

1 = does not know

2 = weight loss between 1 and 3 kg (2.2 and 6.6 lbs)

3 = no weight loss

C Mobility

0 = bed or chair bound

1 = able to get out of bed/chair but does not go out

2 = goes out

D Has suffered psychological stress or acute disease

in the past 3 months

0 = yes 2 = no

E Neuropsychological problems

0 = severe dementia or depression

1 = mild dementia

2 = no psychological problems

F Body Mass Index (BMI) (weight in kg) / (height in m)

2

0 = BMI less than 19

1 = BMI 19 to less than 21

2 = BMI 21 to less than 23

3 = BMI 23 or greater

J How many full meals does the patient eat daily?

0 = 1 meal

1 = 2 meals

2 = 3 meals

K Selected consumption markers for protein intake

At least one serving of dairy products

(milk, cheese, yogurt) per day?

yes no

Two or more servings of legumes

or eggs per week?

yes no

•

•

•

Meat, fish or poultry every day

yes no

0.0 = if 0 or 1 yes

0.5 = if 2 yes

1.0 = if 3 yes .

L Consumes two or more servings

of fruits or vegetables per day?

0 = no 1 = yes

M How much fluid (water, juice, coffee, tea, milk…) is consumed per day?

0.0 = less than 3 cups

0.5 = 3 to 5 cups

1.0 = more than 5 cups .

N Mode of feeding

0 = unable to eat without assistance

1 = self-fed with some difficulty

2 = self-fed without any problem

O Self view of nutritional status

0 = views self as being malnourished

1 = is uncertain of nutritional state

2 = views self as having no nutritional problem

P In comparison with other people of the same age,

how does the patient consider his/her health status?

0.0 = not as good

0.5 = does not know

1.0 = as good

2.0 = better .

Q Mid-arm circumference (MAC) in cm

0.0 = MAC less than 21

0.5 = MAC 21 to 22

1.0 = MAC 22 or greater .

R Calf circumference (CC) in cm

0 = CC less than 31 1 = CC 31 or greater

Assessment (max. 16 points)

.

Screening score

Total Assessment

(max. 30 points)

.

Screening

Screening score (subtotal max. 14 points)

12 points or greater Normal – not at risk – no need to complete assessment

11 points or below Possible malnutrition – continue assessment

Malnutrition Indicator Score

17 to 23.5 points at risk of malnutrition

Less than 17 points malnourished

Assessment

G Lives independently (not in a nursing home or hospital)

0 = no 1 = yes

0 = yes 1 = no

Takes more than 3 prescription drugs per dayH

0 = yes 1 = no

Pressure sores or skin ulcersI

Ref.:

© Nestlé, 1994, Revision 1998. N67200 12/99 10M

Mini Nutritional Assessment

MNA

R

Last name:

First name: Sex: Date:

Age: Weight, kg: Height, cm: I.D. Number:

Guigoz Y, Vellas B and Garry PJ. 1994. Mini Nutritional Assessment: A practical assessment tool

for grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Facts and Research in Gerontology. Supplement

#2:15-59.

Rubenstein LZ, Harker J, Guigoz Y and Vellas B. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) and

the MNA: An Overview of CGA, Nutritional Assessment, and Development of a Shortened Version

of the MNA. In: “Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA):Research and Practice in the Elderly”. Vellas

B, Garry PJ and Guigoz Y, editors. Nestlé Nutrition Workshop Series. Clinical & Performance

Programme, vol.1. Karger, Bâle, in press.

fig0001 Figure 1 Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA).

ELDERLY/Nutritional Management of Geriatric Patients 2033

and neoplastic causes in the mouth or esophagus,

mechanical or neuromuscular causes, or a pharyngeal

diverticulum. Management is primarily directed to

resolution of the causative factors, but there will be

an intervening period of a need for nutritional main-

tenance, or, where the underlying cause cannot be

treated, long-term nutritional support may be re-

quired. Stroke, motor neurone disease, and, less com-

monly, Parkinson’s disease may be associated with

severe swallowing problems. Following an acute

stroke, swallowing difficulties are generally transient

and resolve within a week. However, in 15% of pa-

tients, swallowing impairment with risk of aspiration

excludes oral nutrition. Dehydration leads to rapid

deterioration, and intravenous fluids are required

in the first few days. Three options are available

for nutritional maintenance until safe swallowing

returns. Parenteral nutrition is only practical for a

few days and has a very limited role in poststroke

management. Fine-bore nasogastric tube feeding is

commonly the interim measure for nutritional provi-

sion. In the first week or so, emphasis is on energy and

protein intake, but a balanced nutrient provision with

attention to micronutrients and mineral content

becomes essential for longer-term management. Per-

cutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is well tolerated

and is the method of choice for long-term manage-

ment. The benefits of early PEG feeding have yet to be

established, but ongoing randomized trials should

provide evidence-based guidance.

0029 In motor neurone disease, the early stages of

dysphagia are managed by thickening all fluids and

liquidizing and adapting solid food to a thick custard

consistency. Unfortunately, food consumption can

easily take on an ‘eat to live’ meaning with the loss

of social and pleasurable aspects of eating.

0030 Alzheimer’s disease is the commonest cause of de-

mentia in later life. Weight loss is usual, sometimes

even early in the disease, and vitamin deficiencies and

disturbed eating behavior are common. Where the

cognitively impaired individual lives alone and has

difficulty in buying or preparing an adequate diet or

forgets meals, the cause of the weight loss is readily

apparent. In later stages, restlessness and agitation

may result in excessive energy expenditure, or aver-

sion to food may develop. Often, however, there is no

obvious cause of weight loss. Carers may be able to

provide accurate dietary information to enable moni-

toring of the patient’s nutritional status using the

MNA. There is current interest in the possible role of

inadequate intake of folate and raised homocysteine

in the etiology of cognitive impairment. However, it is

also likely that vitamin deficiencies may develop as a

result dementia. Antioxidant vitamins may have neu-

roprotective effects and, in the experimental animal,

can improve cognitive function. High-saturated-fat

diets are reported to be associated with an increased

likelihood of cognitive impairment, whereas polyun-

saturated fats have a negative influence. Tube feeding

of people with advanced dementia has no measurable

influence on survival and raises important practical

and ethical concerns.

0031Decline in glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes

mellitus is increasingly common in old age. A raised

2-h postprandial glucose test is associated with in-

creased mortality. Dietary management has changed

considerably over recent years. From the early 1990s,

reducing dietary fat intake, particularly saturated fat,

has been recommended. Currently, a reduction in

saturated and trans-fats is advised, but no restriction

on monosaturated and polyunsaturated fats. Increas-

ing emphasis is also placed on replacing high-with

low-glycemic-index foods. A change in lifestyle is

important in both prevention and treatment, and it

is inappropriate to consider diabetes in isolation from

other risk factors. Hypertension affects at least 50%

of older diabetics, and reduced sodium intake

enhances the overall management of high blood

pressure.

Undernutrition in Institutionalized

Patients

0032Many hospital patients and residents of long-term

care facilities cannot feed themselves, and many are

malnourished. Since the serving and checking of

meals have become a ‘nonnursing duty’ in the UK,

awareness of the patient’s nutrient intake may be

limited. Meals are often kept for some time in heated

wagons before serving, and some nutrients are largely

destroyed. Older people are more likely to eat food

provided when it is served warm, with portion size

individualized, and the eating environment is con-

sidered. In one study, in which plated meals were

weighed before and after serving, elderly patients

were shown often to have inadequate time or ability

to cut and eat their meals. When all food was cut up

into bite-sized pieces, food consumption improved

significantly. Food must also be placed within reach

of disabled patients. An uncluttered, well-lit dining

room with minimal distractions, providing consist-

ent seating at mealtimes and attractive table settings

will enhance eating. Attention to poor hearing en-

hances enjoyment of mealtime conversation. People

with physical disabilities may benefit from feeding

aids such as nonskid place mats, weighted cutlery

with thick handles, plates with wide, curved lips

that help keep food on the plate, and cups with

easy-grip handles and special lids for sipping. Cyclical

menus should be available, recognizing individual

2034 ELDERLY/Nutritional Management of Geriatric Patients

preferences and offering properly prepared and appe-

tizing meals. Dividing up the daily food ration into

lighter, more frequent snacks may be more acceptable

than the traditional three meals a day. Special events

such as picnics and family dinner parties and special

menus for festive occasions such as birthdays will

encourage an interest in eating. Patients requiring a

softer or liquid diet would benefit by having their

food presented creatively.

0033 Water is an important nutrient that is often over-

looked. Thirst lessens with age, so older people need

to adopt the habit of drinking fluids regularly, or

dehydration can occur easily. This is a particular

problem in the physically or mentally frail and the

institutionalized, who are especially susceptible to the

dehydrating effects of fever, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Undernutrition in People at Home

0034 The elderly person living alone is at especial risk of

malnutrition. Grief from the loss of a spouse or family

and friends, loneliness and depression, greater use

or abuse of alcohol, which may substitute for an

adequate food intake, lack of sufficient money for

food, and disability affecting shopping or preparation

of food may all contribute. Poor vision is also an

independent determinant of poor eating, leaving

people less confident in their ability to cook and less

able to get out for groceries. Support from relatives,

neighbors, and homecare assistants providing and

preparing food deserves recognition. Eating should

be a social event, and older people should be encour-

aged to eat with family and friends whenever

possible.

0035 Relevant community services for older people in-

clude meals on wheels, which provide hot meals up to

7 days per week to homebound people in their own

homes. However, arrangements are often inflexible,

and there is limited ability to conform to special diet-

ary needs. Frozen meals delivered weekly and which

can then be easily reheated in a microwave oven may

be a more appropriate and palatable alternative. Day

centers and luncheon clubs have a useful role in sup-

plementing the diet and reinforce the social aspects of

feeding. An emergency store of essential food items in

case of unexpected illness or bad weather is a useful

precautionary measure.

See also: Aging – Nutritional Aspects; Ascorbic Acid:

Properties and Determination; Carotenoids: Occurrence,

Properties, and Determination; Cholecalciferol:

Properties and Determination; Cobalamins: Properties

and Determination; Dietary Reference Values; Dietary

Requirements of Adults; Elderly: Nutritional Status;

Nutritionally Related Problems; Energy: Intake and

Energy Requirements; Folic Acid: Properties and

Determination; Iron: Properties and Determination;

Malnutrition: The Problem of Malnutrition; Minerals –

Dietary Importance; Protein: Requirements

Further Reading

Cummings JH and Bingham SA (1998) Diet and the

prevention of cancer. British Medical Journal 317:

1636–1640.

Department of Health (1992) The Nutrition of Elderly

People. Great Britain Committee on Medical Aspects

of Food Policy Working Group on the Nutrition of

Elderly People. Report on Health and Social Subjects.

No. 43. London: Stationery Office.

Ebrahim S and Davey-Smith G (1996) Health Promotion

in Old People for the Prevention of Coronary Heart

Disease and Stroke. Health Promotion Effectiveness

Reviews. London: Health Education Authority.

Fiatarone MA, O’Neill EF, Ryan ND et al. (1994) Exercise

training and nutritional supplements for physical frailty

in very elderly people. New England Journal of Medicine

330: 1769–1775.

Finch S, Doyle W, Lowe C et al. (1998) National Diet and

Nutrition Survey: People Aged 65 years and Older.

Volume 1: Report of the Diet and Nutrition Survey.

London: Stationery Office.

Fletcher A and Rake C (1998) Effectiveness of Interven-

tions to Promote Healthy Eating in Elderly People

Living in the Community: A Review. Health Promotion

Effectiveness Reviews No. 8. London: Health Education

Authority.

Gariballa SE and Sinclair AJ (1997) Diagnosing under-

nutrition in elderly people. Reviews in Clinical Geron-

tology 7: 367–371.

Horwitz A, MacFadyen DM, Munro H, Scrimshaw NS,

Steen B and Williams TF (1989) Nutrition in the Elderly.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lilley J and Hunt P (1998) Opportunities for and Barriers

to Managing in Dietary Behaviour in Elderly People.

London: Health Education Authority.

Lipschitz DA (1995) Approaches to the nutritional support

of elderly patients. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 11:

715–724.

McGee M and Jensen GL (2000) Nutrition in the elderly.

Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 30: 372–380.

Roe L, Hunt P, Bradshaw H and Rayner M (1997) Review

of the Effectiveness of Health Promotion Interventions

to Promote Healthy Eating. London: Health Education

Authority.

Seiler WO and Stahelin HB (eds) (1999) Malnutrition in the

Elderly. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Vellas BJ, Garry PJ and Guigoz Y (eds) (1999) Research and

Practice in the Elderly (Nestle

´

Nutrition Workshop

Series. Clinical and Performance Programme, vol. 1.

Basel: Karger.

Walls AW, Steele JG, Sheiham A, Marcenes W and Moyni-

han PJ (2000) Oral health and nutrition in older people.

Journal of Public Health Dentistry 60: 304–307.

ELDERLY/Nutritional Management of Geriatric Patients 2035

Electrical Supplies See Power Supplies: Use of Electricity in Food Technology

ELECTROLYTES

Contents

Analysis

Water–Electrolyte Balance

Acid–Base Balance

Analysis

G R Ahmad, California State University,

San Bernardino, CA, USA

D R Ahmad, University of California, Riverside, CA,

USA

This article is reproduced from Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Copyright 1993, Academic Press.

Electrolytes and their Significance

0001 Electrovalent solids exist as crystal lattices composed

of ions bound together by a strong electrostatic force of

attraction between positive and negative charges. The

solutions of such substances in water conduct electri-

city and are therefore called electrolytes. Electrolytes

are classified as anions or cations, depending upon

their direction of movement in an electric field. If an

electrolyte bears a positive charge, it will migrate to the

cathode (negative pole) and is called a cation. Sodium

and potassium are common examples of cations. If the

electrolyte bears a negative charge, it will migrate to

the anode (positive pole) and is called an anion. Chlor-

ide and bicarbonate are examples of anions.

0002 In body fluids, the major electrolytes exist as free

ions, while the trace metals primarily occur in com-

bination with proteins. The electrolytes play very

important roles in the physiology of living organisms.

In the human body, virtually every metabolic process

is dependent on, or is affected by, electrolytes. Elec-

trolytes are involved in the maintenance of the body’s

osmotic pressure, water distribution in the various

body fluid compartments, maintenance of proper

pH, involvement in oxidation – reduction reactions,

acting as cofactors for enzymes, and regulation

of neuromuscular irritability or excitability. Thus,

abnormal levels of electrolytes could be the cause

or consequence of a variety of physiological dis-

orders, which make the determination of eletrolytes

one of the most important functions of clinical la-

boratories. (See Coenzymes; pH – Principles and

Measurement.)

0003The major electrolytes found in the body are

sodium (Na

þ

), potassium (K

þ

), calcium (Ca

2þ

), mag-

nesium (Mg

2þ

), chloride (Cl

), bicarbonate (HCO

3

),

phosphate (HPO

4

2

), and sulfate (SO

4

2

). In clinical

laboratories, the most common electrolytes requested

in a medical diagnosis are commonly referred to as

the ‘electrolyte profile.’ This panel includes four elec-

trolytes: HCO

3

,Cl

,Na

þ

and K

þ

.(See Calcium:

Physiology; Magnesium; Potassium: Physiology;

Sodium: Physiology.)

Specimens Required for Electrolyte

Analysis

0004Electrolytes can be assayed from many body

fluids, including serum, heparinized plasma, whole

blood, vitreous humor, sweat, urine, gastrointestinal

fluid, and aqueous extract from feces. In clinical la-

boratories, serum and urine are the body fluids from

which electrolyte analyses are most frequently per-

formed. These fluids are easily obtained from the pa-

tient, and the reference levels (normal) for these fluids

are available. When the electrolyte level of body fluid

is required, serum is considered the most practical

specimen. When electrolytes are to be determined

from urine, a timed collection is the preferred method.

Timed-collection specimens are needed to allow a

comparison of values with reference ranges or for the

determination of rates of electrolytes lost from the

body. These specimens can be stored at 2–4

C or can

be frozen for delayed analysis. The average serum

levels of common electrolytes are as follows:

.

0005bicarbonate (expressed as total carbon dioxide),

22–31 mmol l

1

;

.

0006chloride, 98–106 mmol l

1

;

2036 ELECTROLYTES/Analysis