Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

foam/gel and soil are rinsed away, again using the

pressurized water supply.

0025 Foam cleaning is particularly useful for cleaning

the outside of complex machinery, walls, and other

large surfaces, as these surfaces can be easily and

quickly covered with a foam layer.

0026 A wide range of detergents from strongly alkaline

to acidic are suitable for use with foam cleaning, so

that most soiling in the food industry can be dealt

with. Foam cleaning is typically not suited for sur-

faces covered with a thick soil layer (> 1 mm), as the

foam will not be able to penetrate thick layers com-

pletely and reach the surface.

Advantages and Disadvantages

0027 Foam cleaning is similar to the presoak approach of

pressure jet cleaning, the only difference being related

to the form of the detergent solution that is used

for presoaking. The foam approach has important

benefits:

.

0028 it is a relatively safe way of applying aggressive,

e.g., caustic based detergents on to open surfaces;

.

0029 it is less likely to cause irritant aerosol problems;

.

0030 it is easy to see where the detergent has been

applied;

.

0031 it strongly appeals to operators.

Against these benefits, it has the following disadvan-

tages:

.

0032 it requires special, although not very expensive,

equipment to produce the foam;

.

0033 it could give a false feeling of security because

everything is covered with a white clean blanket,

also if the soil cannot be attacked effectively.

.

0034 the detergent solution has to be prepared manually.

Disinfection can be done with the same equipment,

except that a small tank (15 l) provided with a tube

and spray-lance with a vee-jet is used. The tank is

filled with 10 l of disinfectant solution and is then

pressurized with 5-bar compressed air. The disinfect-

ant is applied to the surface using the tube and the

spray-pistol. The advantages of this system are its

simplicity and (therefore) low cost, compared with

more advanced systems.

Booster Pump with Satellites

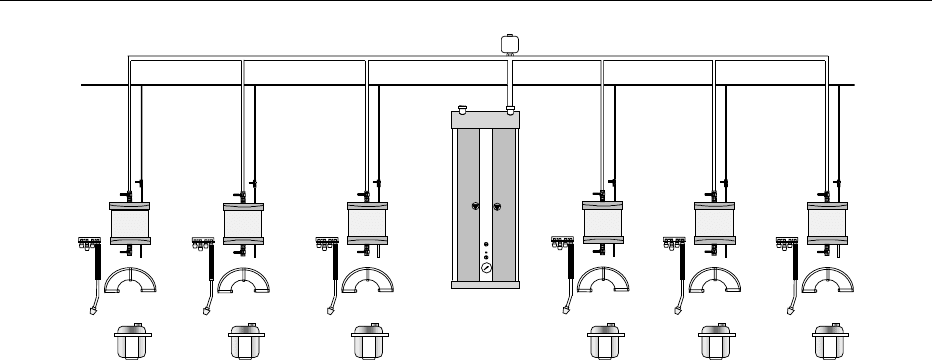

0035A more advanced system consists of a booster pump

(10–25 bar) that provides satellites, with pressurized

(warm) water (Figure 7). The satellite is also con-

nected to a compressed air supply. Using a venturi

system, detergent or disinfectant can be diluted to suit

the application concentration. Because of the connec-

tion with a compressed air supply, the detergent solu-

tion can be applied as a foam. Each satellite can be

used for prerinse, detergent application, rinse, disin-

fectant application, and final rinse. Different satel-

lites, connected to the same booster pump, can carry

out different options (foaming, rinsing, or disinfect-

ing). The advantages of this system are that it uses an

automatic detergent solution make-up and fixed pres-

sure and that there is no mobile equipment floating

around. The disadvantage of this system is the higher

capital investment compared with the previous system.

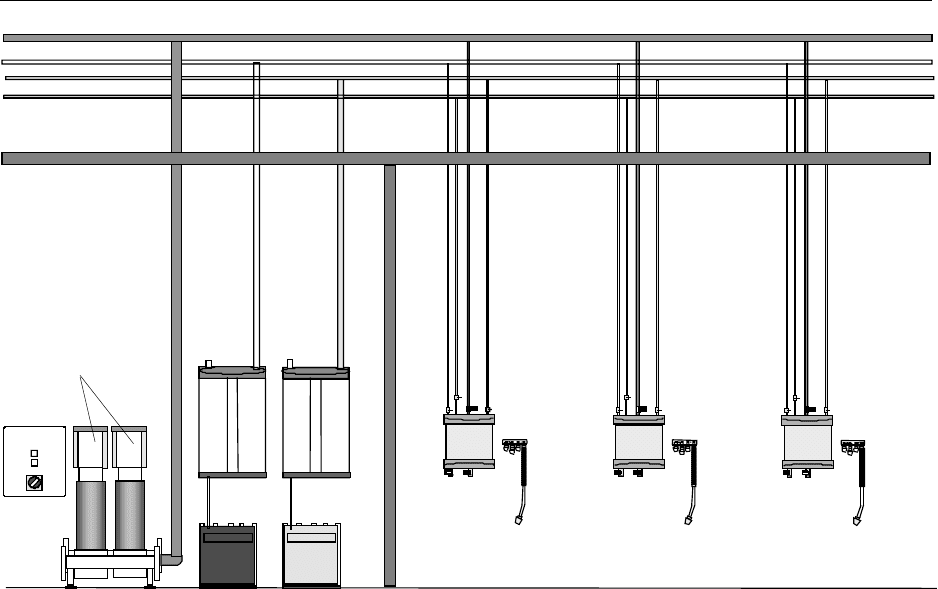

Booster Pump with Central Make-up for Detergent

and Disinfectant

0036For large plants, with many take-off points (Figure 8),

the detergent and disinfectant solution preparation

can be done centrally, using dosing pumps (and flow

meter measurements). Not only pressurized water,

fig0007 Figure 7 Decentralized OPC installation with booster pump and satellites.

1396 CLEANING PROCEDURES IN THE FACTORY/Modern Systems

but also detergent solution, disinfectant solution, and

compressed air flow to each satellite.

0037 The advantages of this system are that it has higher

capacities and does not use concentrated chemicals in

the production area. The disadvantage is that the

same detergent and disinfectant have to be used on

all take-off points.

See also: Cleaning Procedures in the Factory: Types of

Detergent; Types of Disinfectant; Overall Approach;

Factory Construction: Materials for Internal Surfaces

Further Reading

Imholte TJ (1984) Engineering for Safety and Sanitation.

Crystal, MN: Technical Institute of Food Safety.

Karlsson CA-C (1999) Fouling and Cleaning of Surfaces –

The Influence of Surface Characteristics and Operating

Conditions. Lund, Sweden, Lund University.

Lelieveld HLM (2000) Hygienic design of factories and

equipment. In: The Microbiological Safety and Quality,

pp. 1656–1690. Guithersburg, MD: Aspen.

Shapton DA and Shapton NF (eds) (1998) Principles and

Practices for the Safe Processing of Foods. Cambridge,

UK: Woodhead.

Wilson DI, Fryer PJ and Hasting APM (eds) (1999) Fouling

and Cleaning in Food Processing ’98. Proceedings of a

Conference at Jesus College, Cambridge. Brussels: Dir-

ectorate-General Science, Research and Development.

Compressed air

20 bar

Pre-diluted foam product

Pre-diluted disinfectant

Foam product Disinfectant

Pump

fig0008 Figure 8 Central OPC installation with central booster pump, satellites, and central make-up of media.

CLEANING PROCEDURES IN THE FACTORY/Modern Systems 1397

CLOSTRIDIUM

Contents

Occurrence of

Clostridium perfringens

Detection of

Clostridium perfringens

Food Poisoning by

Clostridium perfringens

Occurrence of

Clostridium botulinum

Botulism

Occurrence of

Clostridium

perfringens

R G Labbe

´

, University of Massachusetts at Amherst,

Amherst, MA, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 Clostridium perfringens is probably the most wide-

spread of all pathogenic bacteria. There are several

toxigenic types: A, B, C, D, and E. Type A is primarily

associated with human illness. The other types are

associated with diseases of domestic animals. In very

specific situations, type C is occasionally involved in

human illness. Clostridium perfringens is an anaer-

obic, spore-forming organism commonly found in

fresh meat and poultry products. Spores of the organ-

ism can survive many food processing procedures.

Because of its ability to grow over a wide temperature

range, it is often implicated in human food poisoning.

With regard to human illness in general, it should be

noted that, historically, C. perfringens have been most

closely associated with gangrene and wound infec-

tions. In this article, discussion will be limited to its

role in human food poisoning.

Occurrence in Humans, Foods, and the

Environment

0002 Clostridium perfringens is part of the normal intes-

tinal flora in humans and animals and also occurs

widely in soil. It is the most commonly found

Clostridium in clinical specimens. Because of its

abundance in feces, the organism is also found in

sewage-polluted water. Water authorities in certain

localities use its presence as an index of water quality.

0003 Clostridium perfringens has also been found in the

intestinal tract of virtually every animal examined,

with a wide variation within and between species.

Although the levels of C. perfringens in healthy adults

are relatively small compared with other strict

anaerobes, C. perfringens can be isolated from the

gut of virtually all humans. In infants, adult levels

are established by 6 months of age.

0004Early studies on the incidence of C. perfringens

focused on the isolation of so-called heat-resistant

strains (those whose spores could survive – and be

activated by – heating at 100

C for 60 min) since

it was thought that this group was more likely to

survive cooking than less heat-resistant, i.e., ‘heat-

sensitive’ spore strains. By the mid-1960s, it became

apparent that heat-sensitive strains were equally

capable of causing outbreaks of food poisoning. In

epidemiological investigations, no distinction is now

made between the two groups.

0005There is a wide variation in the total C. perfringens

count in human feces. However, in healthy adults,

the values are usually 10

3

–10

5

per gram (Table 1).

Patients in outbreaks carry 10

6

–10

8

per gram. The

level of spores of this organism in feces is within one

log of the total count. The procedure used to obtain

the spore count – heating the sample at 75–80

C for

10–20 min – also eliminates competing microflora.

The fecal spore count is one of several laboratory

criteria for investigating outbreaks caused by this

organism (see below).

0006It has become apparent that the elderly, although

healthy, often carry relatively high (total or spore)

numbers of C. perfringens, often above 10

6

per

gram. This phenomenon is not attributable to inges-

tion of elevated levels of C. perfringens since surveys

have been conducted in extended-care facilities where

the daily intake was monitored. Such high levels in

asymptomatic elderly limit the usefulness of examin-

ing stools of patients for elevated levels of C. perfrin-

gens. In such situations, other criteria for confirming

outbreaks, discussed below, are available.

0007Early studies on the incidence of C. perfringens in

raw foods focused on heat-resistant strains, thus

understating true levels of the organism. Representa-

tive results of many market and slaughterhouse

surveys, conducted over the years, are presented in

Table 2. No distinction is made between vegetative

1398

CLOSTRIDIUM

/Occurrence of

Clostridium perfringens

cells and spores. The latter would obviously be more

able to withstand subsequent cooking procedures.

The data for meat and poultry were from surveys

conducted in North America and the UK. Results

from Japan are consistently lower. It should also be

noted that such surveys have been carried out using a

variety of methods for enrichment, heat selection,

selective plating, and confirmation. It is clear from

Table 2 that the organism is abundant in raw, protein-

rich foods. The source of the organism is the intestinal

contents of these animals. As noted above, the feces of

all animals examined, domestic and wild, contain

C. perfringens. In the case of fish and shellfish, there

are wide fluctuations in isolation rates, presumably

depending on the degree of water pollution. Such

products are rarely involved in outbreaks of C. per-

fringens food poisoning.

0008The organism is also found in many types of pro-

cessed foods, although at a low level. However, in

some cases, such as soups and sauces, only short

heating times are required for preparation. Other

items, such as herbs and spices (well known for their

high general bacterial spore levels, including C. per-

fringens) are often added to large amounts of cooked

foods. Slow cooling or inadequate reheating of such

foods can result in the large number of C. perfringens

necessary to cause food poisoning. Oxygen is driven

off during cooking, creating ideal conditions for

growth of this organism.

0009Clostridium perfringens is part of the microflora of

soil and is present at levels of 10

3

–10

4

per gram. Even

in Antarctica, moist soil samples examined contained

this organism. In view of its widespread presence in

soil, its presence in air and dust (including kitchen

dust) is not surprising. In the case of marine

sediments, there is a close relationship between the

amount of fecal pollution and the number of C.

perfringens.

Food Poisoning

0010Food poisoning attributable to C. perfringens usually

occurs 8–24 h after the ingestion of temperature-

abused food containing large numbers of vegetative

cells. Symptoms last 1–2 days and generally include

diarrhea and severe abdominal cramps. Vomiting is

not common, and fever is rare. Type A cells are usu-

ally responsible. A more severe type of illness, caused

by type C, occurs among young adults of the

tbl0002 Table 2 Results of surveys of the incidence of C. perfringens in

food and feeds

Raw food types Incidence (%)

Meat and poultry

Poultry carcass 58

Frozen chicken 63

Beef carcass 26

Pork carcass 66

Lamb carcass 85

Ground beef 50–70

Beef liver 26–50

Veal 82

Pork 37

Pork sausages 39

Lamb, mutton 52

Fish and shellfish

Fish, body surface 84

Fish, alimentary tract 82

Vacuum-packed fish 67

a

Oysters 100

Trout 0

Miscellaneous

Spices and herbs 42

Dehydrated soups and sauces 18

Animal feeds 35

a

Incidence of Clostridium; predominant species is C. perfringens.

tbl0001 Table 1 Representative surveys of C. perfringens cells and spores in feces from various population of various countries

Population Country Cell type Levels(pergram)

Healthy adults USA, UK Total viable count 10

3

–10

4

Young patients UK Total viable count 3 of 6, 10

4

0 of 10, 10

6

Elderly adults Japan Total viable count 5 of 30, 10

7

Elderly patients UK Total viable count 10 of 11, 10

4

5 of 11, 10

6

Elderly mental patients UK Total viable count 6 of 10, 10

4

3 of 10, 10

6

Health adults Canada Spore count

a

10

3

–10

4

Food-poisoning patients UK Spore count

a

56 of 66, 10

6

–10

8

Food-poisoning patients USA Spore count

a

2.0 10

4

–4.0 10

8

Mean, 10

7

Food-poisoning patients USA Spore count

a

<10

3

–2.2 10

5b

a

Fecal samples heated at 80

C for 10 min.

b

30 days after illness.

CLOSTRIDIUM

/Occurrence of

Clostridium perfringens

1399

highlands of New Guinea. It is necrotizing (necrosis:

death of areas of tissue surrounded by healthy parts),

hemorrhagic jejunitis (inflammation of the jejunum,

the second portion of the small intestine extending

from the duodenum to the ileum) which is often

called ‘pig-bel’ (enteritis necroticans) because it

follows traditional pig feasting.

0011 It should be noted that ingestion of low levels of

microbial spores, including Clostridium botulinum

and C. perfringens, is a common occurrence and not

a public safety issue for adults. Only when these

spores have been allowed to germinate and grow in

food products do they pose a health threat.

Mechanisms of Entry into the Food Chain

0012 The vegetative cells and spores of C. perfringens are

common surface contaminants of fresh meat and

poultry carcasses. This is not surprising in view of

the common occurrence of the organisms in the intes-

tine of these animals. They can be easily disseminated

during processing steps such as skinning, eviscer-

ation, and scalding. Unlike the case for Salmonella,

the absence of this organism from fresh meat and

poultry is an unreasonable expectation. Furthermore,

the mere presence of C. perfringens (as spores) surviv-

ing cooking will not cause outbreaks of foodborne

illness. For the latter to occur, gross mishandling and

temperature abuse must always be involved. (See

Meat: Eating Quality; Hygiene; Poultry: Chicken;

Ducks and Geese; Turkey.)

Fate During Processing and Storage

0013 Temperature is the single most important determinant

of the survival and multiplication of C. perfringens

subsequent to slaughter and packaging. Generation

times as low as 8–10 min have been reported for this

organism at its optimum growth temperature. Other

considerations affecting growth include absence of

oxygen, water activity, pH, and salt content. How-

ever, alterations of these usually involve further pro-

cessing steps, and epidemiological investigations have

consistently implicated fresh meat and poultry as

sources of the organism. (See Meat: Preservation.)

0014 The fate of C. perfringens during processing and

storage depends on the form of the organism, i.e.,

vegetative cell or spore. Both are present in fresh

meat and poultry, but each requires different consider-

ations with regard to immediate or potential hazard.

0015 Vegetative cells can grow over the temperature

range of 15–50

C, with optima between 43 and

46

C. Even between 60 and 70

C, viability may be

maintained, but vegetative cells are rapidly inacti-

vated at 75

C. Considering the short generation

time of the organism, the slow attainment of a safe

interior temperature can actually increase the initial

number of organisms and permit more cells to sur-

vive. Thus, the rate at which the interior temperature

is attained may also influence the thermal survival of

vegetative cells. For example, rump roast cooked to

an internal temperature of 77

C in 2.25 h has been

shown to retain significant numbers of viable C.

perfringens cells. However, experiments with chicken

breast and thigh have shown complete killing of 10

8

vegetative cells when the pieces were cooked in water

at 82

C, and the internal temperature of 77

C was

attained in 20 min or less. The standard dictum that

cooked meat should be kept above 62.8

C or below

10

C will insure safety of properly heated food.

0016Most C. perfringens spores isolated from meat and

poultry are of the heat-sensitive variety. These are

killed in a few minutes at 100

C. Unfortunately,

spores of the heat-resistant variety are also present

in lower numbers. These have D

100

(decimal reduc-

tion value at 100

C) values of 6–17 min and can

survive cooking procedures (which themselves drive

off oxygen), germinate, and resume vegetative cell

growth given the proper conditions, principally a

suitable temperature.

0017The effect of low-temperature storage on C. per-

fringens cells is important because food safety with

regard to this organism is based largely on proper

refrigerated holding. Clostridium perfringens vegeta-

tive cells are sensitive to low temperature, e.g., re-

frigerated storage. Slow die-off occurs under these

conditions. Similarly, long-term (several weeks) freez-

ing slowly inactivates vegetative cells. The initial

freezing step reduces the population approximately

10-fold. Surprisingly, vegetative cells die more rapidly

at 5

C than at 20

C. As one would expect, spores

are considerably more resistant. They are virtually

unaffected by refrigerated storage and only somewhat

inactivated by freezing. Indeed, frozen storage in the

spore state is routinely used for culture carriage.

0018Before spores can resume vegetative cell growth,

they must germinate. Proper nutrients must be avail-

able, and these are readily available in meat and

poultry products. Viable bacterial spores are trad-

itionally measured by heating a culture at an elevated

temperature (75–80

C, depending upon the strain)

for 10–20 min and performance routine plating pro-

cedures. This procedure ‘activates’ the spore popula-

tion (and inactivates any vegetative cells). In the case

of raw food, this function is effectively achieved by

routine cooking procedures. Optimal temperatures

for germination are similar to those for vegetative

cell growth, in a pH range of 5.5–7.0.

0019It is difficult to specify the time required for cells of

C. perfringens to multiply in foods to attain toxic

1400

CLOSTRIDIUM

/Occurrence of

Clostridium perfringens

numbers, but it has been observed that meats stored

at a ‘warm’ temperature for at least 2 h after cooking

were common factors in many outbreaks. The hazard

is magnified when such food is allowed to cool slowly

for several hours, e.g., overnight at room tempera-

ture, as has occurred with large turkeys or large bulk

of other meats.

0020 The multiplication of bacteria is a logarithmic

function. The rate at which a product may accumu-

late harmful numbers of cells will depend to a large

extend on the size of the inoculum. The temperature

at which cooked foods is held or stored is the other

highly dependent variable. As mentioned above, that

is especially true with C. perfringens in view of its

ability to grow at relatively elevated temperatures.

See also: Beef; Clostridium: Detection of Clostridium

perfringens; Food Poisoning by Clostridium perfringens;

Meat: Preservation; Pork; Poultry: Chicken; Ducks and

Geese; Turkey; Sheep: Meat

Further Reading

Labbe

´

R (2000) Clostridium perfringens. In: Lund B, Baird-

Parker T and Gould G (eds) The Microbiological Safety

and Quality of Food, vol. II, pp. 1110–1135. Gaithers-

burg, MD: Aspen.

Labbe

´

R (2001) Clostridium perfringens. In: Downes FP

and Ito K (eds) Compendium of Methods for the

Microbiological Examination of Foods, 4th edn,

pp. 325–330. Washington, DC: American Public Health

Association.

McClane B (2000) Clostridium perfringens. In: Doyle M,

Beuchat L and Montville T (eds) Food Microbiology:

Fundamentals and Frontiers, 2nd edn. pp. 351–372.

Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology

Press.

Smith L and William B (1984) The Pathogenic Anaerobic

Bacteria, 3rd edn. Springfield, IL: Charles Thomas.

Stringer M (1985) Clostridium perfringens type A food

poisoning. In: Borriello S (ed.) Clostridia in Gastrointest-

inal Disease, pp. 117–141. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Detection of

Clostridium

perfringens

R G Labbe

´

, University of Massachusetts at Amherst,

Amherst, MA, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Laboratory Criteria for Confirming

Outbreaks

0001 Laboratory confirmation of an outbreak of Clostri-

dium perfringens food poisoning is based on one of

five criteria: (1) more than 10

5

of the organism per

gram of food; (2) more than 10

6

spores of the organ-

ism per gram of the feces of ill person; (3) the presence

of the same serotype in most of the ill patients; (4) the

presence of the same serotype in the incriminated

food and feces of the patients; and (5) detection of

enterotoxin in feces. Detailed procedures for sero-

typing are available from citations in the Further

Reading section at the end of the next article.

Detection in Raw and Processed Foods

0002Detection of C. perfringens in raw and processed

foods is performed by similar methods. Such foods,

properly handled, would not normally contain more

than 100 C. perfringens cells or spores per gram,

usually much less. In such situations, most probable

number (MPN) test tube procedures can be used for

enumerating low numbers in foods. Iron-containing

milk (iron milk medium, or IMM, i.e., 10 ml of

homogenized milk containing 0.2 g of iron powder)

has been used for this purpose. When incubated at

46

C, C. perfringens produces a typical ‘stormy fer-

mentation’ in IMM. This is defined as the production

of an acid curd (caused by lactic acid fermentation)

with subsequent disruption of the curd by large

volumes of gas. NonMPN enrichment media (trypti-

case–glucose–yeast extract broth), with incubation

at 37

C followed by selective plating on trypticase–

sulfite–cycloserine (or neomycin blood agar) agar

plating, can also be used for enumeration of very

low numbers. Confirmation (see below) is required

in either method.

Detection of Cells in Suspected Food

Poisoning

0003Foods implicated in outbreaks of human food

poisoning would normally contain large numbers of

vegetative cells and relatively few spores. Such food

should be chilled and processed rapidly because of the

susceptible of the cells to cold shock. For delayed

analyses, the highest counts are obtained when

foods (finely chopped if necessary) are mixed 1:1

with 20% glycerol and kept at 20

C or, if shipping

is necessary, placed in a container of dry ice. (See

Food Poisoning: Tracing Origins and Testing.)

0004Selective plating methods are used for enumeration

of viable cells. Enrichment techniques are unneces-

sary for examination of food containing large

numbers of cells. Most plating media depend on

the ability of C. perfringens to reduce sulfite to sul-

fide, which, in the presence of an iron salt, results in

the formation of black colonies owing to ferrous

sulfide. Collaborative analyses have indicated that

CLOSTRIDIUM

/Detection of

Clostridium perfringens

1401

pour-plated tryptose sulfite cycloserine (TSC) with-

out egg yolk is the medium of choice. More consistent

blackening of surface colonies can be obtained by

overlaying plates with sterile media. TSC is commer-

cially available from Unipath (Oxoid). After anaer-

obic incubation for 24 h at 37

C, representative

black colonies (usually 10) must be confirmed. This

is achieved by inoculating a liquid medium, such as

trypticase peptone glucose yeast extract broth or fluid

thioglycollate medium, and incubating at 46

C for

4 h or overnight at 37

C. Tubes of lactose–gelatin

and motility–nitrate are inoculated from each and

incubated at 37

C for 24 h. Clostridium perfringens

is nonmotile, ferments lactose, liquefies gelatin, and

reduces nitrate to nitrite. The number of C. perfrin-

gens per gram is determined by multiplying the

presumptive plate count by the ratio of colonies con-

firmed as C. perfringens. Fecal spore levels are deter-

mined in the same manner, except that the sample is

heated at 75

C for 20 min. The elevated-temperature

MPN methods mentioned above are not recom-

mended for quantification of C. perfringens in out-

break stools.

0005 Surface-plated neomycin blood agar plates are

often used in the UK and can be prepared well in

advance. This medium also provides information on

the hemolytic activity of isolates. However, because

recovery of certain heat-resistant strains may be no

more than 10% on this medium, its use is limited to

outbreak stools or food samples containing large

numbers of C. perfringens. Neomycin blood agar

is not recommended for examining normal food

samples in which the organism is present in low

numbers.

Detection of Enterotoxin in Suspected

Food Poisoning

0006 The ingestion of large numbers of vegetative cells in

incriminated food is followed by multiplication of the

cells in the small intestine. When they sporulate, there

is an accompanying formation of enterotoxin. Lysis

of the sporangia to release the mature spore also

results in the release of enterotoxin.

0007 Serum values of antienterotoxin are of little value

in the diagnosis of C. perfringens food poisoning, and

enterotoxin detection in foods is not a practical

approach. However, detection of the enterotoxin in

stools is of significant diagnostic importance since the

toxin is not detectable in the feces of healthy adults.

Of the criteria listed above, there are occasions when

only detection of enterotoxin in feces is conclusive;

for example, when no food is available, when the

strains are not typeable, or when the incidents con-

cern geriatric patients who may carry large numbers

of the same serotype or spores without symptoms of

food poisoning. Most fecal specimens from food poi-

sonings incidents have enterotoxin concentrations

exceeding 1 mg per gram of feces.

0008Two procedures for detection of enterotoxin in

feces have found widespread use and are effective

when used within 2 days of onset of symptoms.

They are the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA) and the reversed passive latex agglutinations

assay (RPLA). The latter is available as a kit from

Unipath (Oxoid). Although expensive (if obtained

commercially) for multiple samples, the RPLA

method is the simpler of the two. In this method,

latex beads that have been sanitized (treated) with

enterotoxin antiserum are exposed to serial dilutions

of enterotoxin-containing material. After overnight

incubation, the agglutination titer is determined.

Expensive equipment, such as a microplate reader

(needed for ELISA), is unnecessary. However, non-

specific agglutination can occur at very low (near

the detection limit) dilutions. The ELISA method is

preferable when more than occasional samples are

to be assayed. Some half-dozen different ELISA

procedures have been proposed with sensitivities

of 2–5 ng per gram of feces. (See Immunoassays:

Radioimmunoassay and Enzyme Immunoassay.)

Statistics

0009As mentioned above, meat and poultry products are

most commonly involved in cases of human food

poisoning attributed to C. perfringens. The organism

has complex nutritional requirements that are easily

satisfied by such foods. However, cured meats are

rarely implicated. Bacon and ham, for example, are

seldom involved, presumably owing to the presence

of curing salts and the lowered water activity, both

of which inhibit vegetative cell growth. (See Food

Poisoning: Statistics.)

0010Mass feeding establishments are consistently cited

as the source where implicated food was eaten.

Examples of these have included restaurants, cafe-

terias, prisons, schools, and hospitals. All such sites

prepare large amounts of food well in advance of

serving. Opportunities for mishandling of food in

such setting are plentiful.

Detection of

Clostridium perfringens

0011As with other agents of human food poisoning, the

number of outbreaks of food poisoning attributable

to C. perfringens is greatly underreported. This is

particularly true with C. perfringens because of the

relatively mild and short-lived nature of the symp-

toms. In addition, in some countries, e.g., the USA,

1402

CLOSTRIDIUM

/Detection of

Clostridium perfringens

medical personnel are not required to report inci-

dences of outbreaks to central public health officials.

Thus, the data in Table 1 represent only a fraction of

the true number of cases and outbreaks. In Western

countries, the organism ranks second or third behind

Salmonella, Campylobacter,orStaphylococcus aur-

eus in terms of the number of cases of human food

poisoning caused by bacteria. (See Campylobacter:

Properties and Occurrence; Staphylococcus: Proper-

ties and Occurrence.)

See also: Campylobacter: Properties and Occurrence;

Food Poisoning: Tracing Origins and Testing; Statistics;

Immunoassays: Radioimmunoassay and Enzyme

Immunoassay; Staphylococcus: Properties and

Occurrence

Further Reading

Labbe

´

R (2000) Clostridium perfringens. In: Lund B, Baird-

Parker T and Gould G (eds) The Microbiological Safety

and Quality of Food, vol. II, pp. 1110–1135. Guithers-

burg, MD: Aspen.

Labbe

´

R (2001) Clostridium perfringens. In: Downes FP

and Ito K (eds) Compendium of Methods for the Micro-

biological Examination of Foods, 4th edn, pp. 325–330.

Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

McClane B (2001) Clostridium perfringens. In: Doyle M,

Beuchat L and Montville T (eds) Food Microbiology:

Fundamentals and Frontiers, 2nd edn, pp. 351–372.

Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology

Press.

Smith L and Williams B (1984) The Pathogenic Anaerobic

Bacteria, 3rd edn. Springfield, IL: Charles Thomas.

Roberts D, Hooper W and Greenwood M (1995) Practical

Food Microbiology. London: Public Health Laboratory

Service.

Stringer M, Watson G and Gilbert R (1982) Clostridium

perfringens type A: serological typing and methods for

the detection of enterotoxin. In: Corry J, Roberts D and

Skinner F (eds) Isolation and Identification Methods

for Food Poisoning Organisms, pp. 111–135. London:

Academic Press.

Food Poisoning by

Clostridium

perfringens

R G Labbe

´

, University of Massachusetts at Amherst,

Amherst, MA, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0013Historically Clostridium perfringens is best known

for its role in gas gangrene. During the 1940s and

1950s its association with foodborne illness was sug-

gested. In the 1970s the responsible enterotoxin was

isolated and its general mode of action described. In

recent years work has focused on the subcellular

mode of action of this toxin as well as the molecular

genetics of its production.

tbl0001 Table 1 Incidence of confirmed C. perfringens foodborne illness in selected countries

Canada

a

USA

b

England and Wales

c

Japan

d

Year Outbreaks Cases Outbreaks Cases Outbreaks Cases Outbreaks Cases

1980 18 753 25 1463 55 1054 13 5178

1981 15 399 28 1162 46 918 23 3482

1982 18 1420 22 1189 69 1455 11 896

1983 14 324 5 353 68 1624 16 4571

1984 20 888 8 882 68 1716 9 971

1985 13 390 6 1016 64 1466

1986 21 354 3 202 51 896 22 3258

1987 18 369 2 290 51 1266 9 288

1988 42 456 57 1312 19 2671

1989 13 381 7 436 55 901 24 3316

1990 4 84 11 1240 53 1442 24 2503

1991 10 1213 44 733 21 3691

1992 12 912 36 805 17 1086

1993 15 534 38 562 9 1077

1994 12 517 16 1821

1995 14 455

1996 10 1011

1997 6 255 16 1821

a

Todd (personal communication).

b

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA; yearly annual summaries.

c

R Gilbert (personal communication)

d

T Uemura (personal communication).

CLOSTRIDIUM

/Food Poisoning by

Clostridium perfringens

1403

Clinical Features and Characteristics

0001 It is now well established that an enterotoxin is

responsible for symptoms of Clostridium perfringens

food poisoning. The symptoms are typically diarrhea

and severe abdominal cramps (fever and vomiting are

unusual) which occur 8–24 h after ingestion of food

containing large numbers of vegetative cells. Suffi-

cient numbers of cells survive stomach passage and

sporulate in the small intestine.

0002 The sequence of events can be duplicated in the

laboratory by inoculating vegetative cells into a suit-

able sporulation medium. Many different types of

sporulation media have been developed for this, but

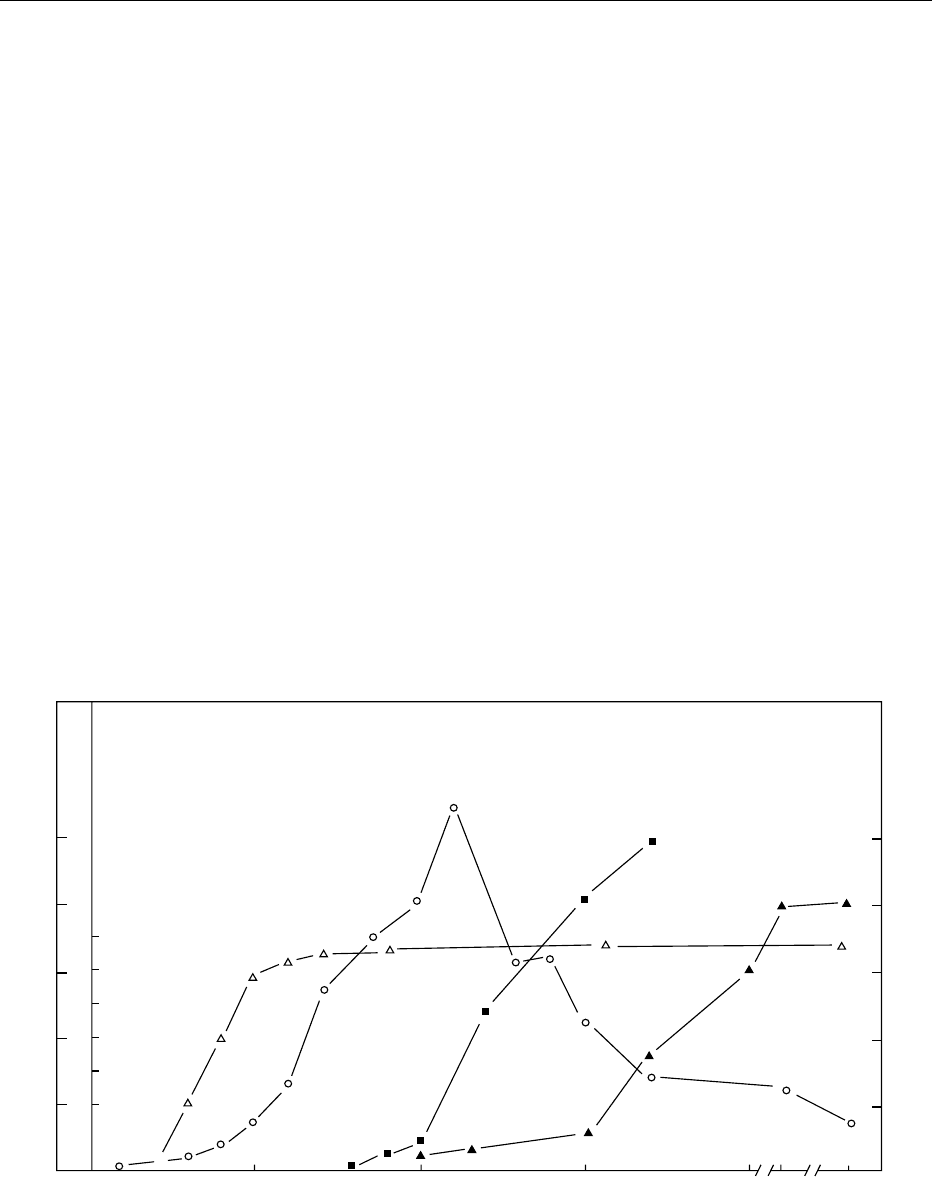

no single one is suitable for all strains. Figure 1 shows

that about 3 h after inoculation of the sporulation

medium, heat-resistant spores develop, followed

closely by the intracellular accumulation of entero-

toxin. Maximum numbers of spores are obtained

after 7 h and free spores can be detected after 10–

12 h. With the liberation of the mature spores from

the sporangia, enterotoxin is released and the con-

centration of enterotoxin in the cell extract there-

fore decreases. The concentration of extracellular

enterotoxin increases in parallel with the increase

in free spores. In humans this corresponds to the

release of enterotoxin into the lumen of the small

intestine.

Site and Mode of Action

0003The enterotoxin of C. perfringens causes fluid accu-

mulation in ligated small intestinal loops (sections),

and overt diarrhea in a large number of experimental

animals. The colon is not affected by the enterotoxin

since, as least in rabbits, there is no change in the

transport of fluid of electrolytes in this tissue. To

determine the mode of action of the toxin, rabbit

small intestines have been perfused with various elec-

trolytes and nutrients after exposure to the toxin. The

effects on intestinal transport and structure were de-

termined. These procedures indicate that the entero-

toxin causes a net secretion of water, sodium, and

chloride. Glucose absorption is inhibited, whereas

potassium and bicarbonate absorption are unaffected.

The sensitivity of the rabbit’s small intestine to the

toxin increases from the upper duodenum down-

ward, with the terminal ileum being the most respon-

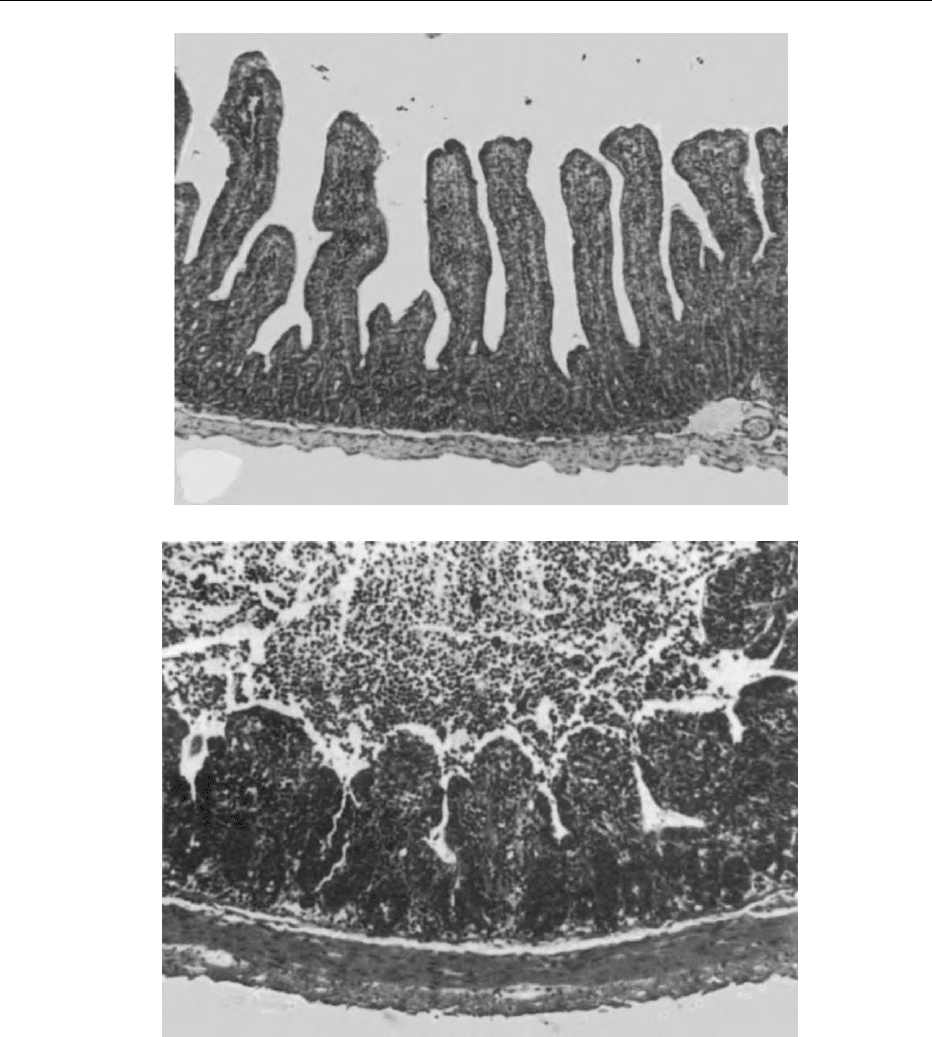

sive. Histological studies have shown that there is

destruction of intestinal epithelial cells at the tips of

20 25 35151050

0

20

40

60

80

100

100

80

60

40

20

Spores log

10

7

6

5

4

3

2

Time (h)

Free spores (%)

Enterotoxin (µg)

fig0001 Figure 1 Time course of intracellular enterotoxin formation and release during sporulation of Clostridium perfringens type A. Open

circles, content (mg) of biologically active enterotoxin per mg of cell protein extract; filled squares, mg of biologically active enterotoxin

per ml of culture filtrate; open triangles, heat-resistant spores per ml; filled triangles, percentage of refractile spores free from

sporangia. Adapted from Labbe

´

R (1989) Clostridium perfringens. In: Doyle M (ed.) Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens, pp. 191–234. New

York: Marcel Dekker.

1404

CLOSTRIDIUM

/Food Poisoning by

Clostridium perfringens

villi (Figure 2). Intestinal brush border membranes

lose their characteristic folded configuration and

large quantities of membrane and cytoplasm are lost

to the lumen. Similar morphological changes occur

after intravenous injection of the enterotoxin. The

brush border (microvillous membrane) of the villus

tip epithelial cells is considered to be the primary site

of action of the enterotoxin.

Food Poisoning by

Clostridium

perfringens

0004In contrast to the effects of cholera toxin and Escher-

ichia coli heat-lable enterotoxin, C. perfringens enter-

otoxin does not increase levels of cyclic adenosine

monophosphate (cAMP) in intestinal mucosa that is

actively secreting fluid.

(a)

(b)

fig0002 Figure 2 Effect of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin on rabbit ileum. (a) Control showing typical villous morphology. (b) Ileum

treated with enterotoxin for 90 min showing shortened villi denuded of epithelial cells. Reprinted from Laboratory Investigation,

Baltimore, USA, with permission.

CLOSTRIDIUM

/Food Poisoning by

Clostridium perfringens

1405