Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

At H P Bulmer’s plant in Hereford, UK, the world’s

largest storage container for alcoholic beverages

holds some 7.3 10

6

l (1.6 10

6

gallons) of product.

0027 The fermentation typically continues with or with-

out control of temperature, pH, or other parameters

until all fermentable sugar has been metabolized into

alcohol. This process can take from 10 days to 12

weeks, depending upon conditions! The modern cider

fermentation plant generally has a facility to control

the temperature, although ambient temperature fer-

mentation still occurs widely (e.g., in farmhouse cider

making). There is no doubt that good control of

temperature can give a more rapid and more consist-

ent fermentation. In France, cider is often fermented

at temperatures below 15

C. (See Fermented Foods:

Origins and Applications.)

Maturation

0028 When fermented to dryness, the cider is frequently

left for a few days on the lees to permit the yeasts to

autolyze, thereby adding cell constituents such as

enzymes, amino and nucleic acids, etc. to the brew.

However, if it is left for too long on the lees, there is a

serious risk of development of off-flavors in the cider.

The cider is separated from the lees (or tank bottoms)

and transferred either directly, or after centrifugal

clarification or filtration, into storage vats (tradition-

ally made of oak). The actual process of maturation

is generally uncontrolled, although, increasingly,

modern commercial cider makers seek to control the

storage temperature and the secondary malolactic

fermentation. The maturation process is only slowly

being understood: malolactic fermentation (carried

out by various lactic acid bacteria) reduces the acidity

by conversion of malic acid to lactic acid. Many other

microbial and biochemical conversions also take

place including modification of the tannins and ester-

ification, e.g., of lactic acid to form ethyl lactate.

Some of the chemical markers of maturation are

now being identified, although judgment as to the

extent of maturation and the suitability of the cider

for use is still an art vested in the cider maker, who

will have many years of experience in judging the

quality of the product.

Final Processing

0029 When required for use, different batches of cider,

generally made from juices of different apple culti-

vars, will be blended by the cider maker to provide

specific flavor attributes. The raw cider may be fined

using agents such as bentonite, gelatin, or chitin and

filtered to give a bright product with no haze. Modern

processing refinements include the use of microfiltra-

tion systems to obviate the need for fining and to

speed the process.

0030If the cider has a high alcohol content, it may be

‘broken back’ to final product strength using water or

dilute apple juice. Other permitted ingredients may be

added such as sugars, intense sweeteners (e.g., sac-

charin), color and/or additional preservative (nor-

mally limited to sulfite, although in some countries,

benzoic or sorbic acids may be used). The finished

blend may be treated with filter aids, such as kiesel-

guhr (diatomaceous earth), to give an optically bright

product or it may again be microfiltered. The most

modern commercial plants use computer-controlled

automated blending and microfiltration to convert

the strong raw cider into commercial product blends.

Cider Packaging

0031Although a small market exists for ‘live’ cask-

conditioned cider, i.e., cider in a wooden or plastic

barrel, to which a small quantity of sugar has been

added, together with a further yeast inoculum, the

majority of commercial cider is carbonated and

pasteurized, or sterile filtered, prior to filling into

kegs, bottles, or cans. (See Packaging: Packaging of

Liquids.)

Keg Cider

0032The cider is carbonated and pasteurized in line,

through a continuous-flow plate heat exchanger. It

is filled into stainless steel kegs in a plant that rinses,

washes, and sterilizes the kegs prior to filling. The

cider is dispensed in on-trade outlets using either

carbon dioxide, or carbon dioxide and nitrogen,

over-pressure through a cooling system designed to

deliver the product into a glass at a temperature of

10 + 0.5

C. This process is similar to that used for

dispensing keg beer.

Bottled Ciders

0033Cider to be filled into glass bottles may either be

carbonated and flash pasteurized, or carbonated and

then in-pack-pasteurized after filling. Since it is

generally not possible to pasteurize PET bottles, the

product will be flash-pasteurized prior to filling.

Bottles will be sealed using either crown closures or

tamper-evident metal or plastic screw caps. Glass

bottles range in size from 25 cl to 1.13 l and PET

bottles from 25 cl to 5 l. Carbonation pressures

generally range from 2.5 to 3.5 bar, the higher initial

pressures being used in PET bottles, which, due to

gaseous diffusion, lose carbonation during storage.

Glass bottled ciders have a shelf-life in excess of 2

years (provided that they are not opened!), whereas

PET bottled ciders generally have a shelf life of 9–12

months, because of loss of carbonation.

1316 CIDER (CYDER; HARD CIDER)/The Product and its Manufacture

Can Cider

0034 The inside of cans for cider is always lacquered to

prevent the product from attacking the metal. Cans

are either of extruded aluminum or of mild steel,

generally with a retained tag. Since sulfur dioxide is

very corrosive to metal, especially if minute pinholes

occur in the lacquer, cider for canning is generally

prepared with little (< 35 mg l

1

total) sulfite. Such

products must, of necessity, be prepared in much

more controlled conditions than general blend

ciders, since at these low sulfite levels, microbial

contamination can lead to the formation of undesir-

able flavours. Cider filled into cans is always bed-

pasteurized, generally at a process level of 30–40

pasteurization units (PUs). Control of dissolved

oxygen levels for can ciders is also most important

to prevent the development of oxidation off-flavors.

Can ciders generally have a shelf-life of 9 months or

less. (See Canning: Principles.)

Secondary Packaging

0035 Bottles and cans are increasingly packaged using trays

and shrink wraps, although the higher-value products

(e.g., vintage and high-strength cider in glass bottles)

are frequently packaged in carboard boxes with or

without dividers.

Labeling of Cider Products

0036 Throughout Europe, cider packs are required to con-

form to EU legislation on food labeling. At the

present time, ingredient and nutritional labeling of

alcoholic products is not required within the EU,

although certain ingredients (e.g., intensive sweeten-

ers) must be labeled. All alcoholic products, including

cider, must display the alcohol content (as % abv) and

the volume. The labeling requirements in other coun-

tries are dependent upon the national legislation.

Special Ciders

Vintage and Single Cultivar Ciders

0037 Vintage ciders are made only from fresh juice from a

named year. Some vintage and other ciders are made

from the juice of a single named apple cultivar.

Sparkling Ciders

0038 Sparkling cider is generally carbonated to a level of

3.5–4 bar pressure. Such products are filled into

‘champagne-style’ bottles with wired closures (gener-

ally plastic-mushroom stoppers). The product is nor-

mally sterile-filtered prior to bottling. Traditionally,

sparkling cider received a secondary ‘in-bottle’ yeast

fermentation (me

´

thode champanoise), but such

processing is rarely seen nowadays. A process used

sometimes is that of cuve

´

e close, in which a secondary

yeast fermentation is done within a sealed tank,

thereby developing a natural carbonation in the cider

prior to bottling. Under EU legislation, it is illegal to

refer to sparkling ciders as ‘champagne cider.’

White cider

0039White cider is prepared by fermenting decolorized

apple juice, or the fermented cider is itself decolor-

ized by treatment with activated charcoal or other

suitable decolorizing agent (e.g., PVPP) prior to final

blending. The term ‘white’ merely indicates that the

product has little or no color – it is not ‘white’ in the

sense that gin or vodka is ‘water white.’

De-alcoholized and Low-Alcohol Ciders

0040De-alcoholized ciders are prepared by removing the

alcohol from strong cider, by thermal evaporation,

reverse osmosis, or other suitable technology to give

a product with an alcohol content not in excess of

0.5% abv. De-alcoholized cider lacks body and flavor

and is not sold commercially. Low-alcohol cider

(< 1.2% abv) is prepared either using a stopped fer-

mentation or by fortification of de-alcoholized cider

with apple juice and/or other ingredients to provide a

product with a flavor and aroma close to that of

normal alcoholic cider.

Organic cider

0041Following consumer interest in organic foods, a

number of cider makers now offer cider made only

from fruit grown in accordance with EU Regulations

governing organic horticultural practices. The fruit is

pressed separately from nonorganic fruit, and at

present, it can be treated only with gaseous sulfur

dioxide. The other ingredients included in the prod-

uct must also conform with current legislation on

organic products.

See also: Alcohol: Properties and Determination; Barrels:

Wines, Spirits, and Other Beverages; Canning:

Principles; Lactic Acid Bacteria; Preservatives:

Classifications and Properties; Tannins and

Polyphenols; Yeasts

Further Reading

AICV (2000) Code of Practice for the Production of Cider,

Perry and Fruit Wine in the EU. Revised 2000. Brussels:

AICV.

Beech FW (1972) English cidermaking: technology, micro-

biology and biochemistry. In: Hockenhull DJD (ed.)

Progress in Industrial Microbiology, vol. 11, pp. 133–

213. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

CIDER (CYDER; HARD CIDER)/The Product and its Manufacture 1317

Beech FW and Davenport RR (1983) New prospects and

problems in the beverage industry. In: Roberts TA and

Skinner FA (eds) Food Microbiology: Advances and Pro-

spects (S.A.B. Symposium Series No. 11), pp. 241–256.

London: Academic Press.

Charley VLS (1949) The Principles and Practice of Cider-

making. London: Leonard Hill.

Jarvis B (2001) Cider, perry, fruit wines and other alcoholic

beverages. In: Arthey D and Ashurst PR (eds) Fruit Pro-

cessing, 2nd edn. pp. 111–148. Gaithersburg, MA:

Aspen Publishers Inc.

Jarvis B, Forster MJ and Kinsella WP (1995) Factors

affecting the development of cider flavour. In: Board

RG, Jones D and Jarvis B (eds) Microbial Fermentations:

Beverages, Foods and Feeds (SAB Symposiuim Series

No. 24) Journal of Applied Bacteriology 79 (supple-

ment): 5S–18S.

Lea AGH (1995) Cidermaking. In: Lea AGH and Piggott JR

(eds) Fermented Beverage Production, pp. 66–

96.London: Blackie Academic & Professional.

Williams RR (ed.) (1991) Cider and Juice Apples: Growing

and Processing. Bristol: University of Bristol.

Chemistry and Microbiology of

Cidermaking

B Jarvis, Ross Biosciences Ltd, Ross-on-Wye, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 The fermentation of apple juice to cider can occur

naturally through the metabolic activity of the yeasts

and bacteria present on the fruit at harvest, which are

then transferred into the apple juice on pressing.

Other organisms, arising from the milling and press-

ing equipment and the general environment, can also

contaminate the juice at this stage. Unless such organ-

isms are inhibited, e.g., through the use of sulfur

dioxide, the resulting mixed fermentation will yield

a product that varies considerably from batch to

batch, even if the composition of the apple juice for

fermentation is identical.

0002 Hence, control of the indigenous and adventitious

microorganisms, followed by deliberate inoculation

with a selected strain of yeast, is the preferred com-

mercial route for the production of cider. Transfer of

the fermented juice into (traditionally oak) matur-

ation vessels will result in a secondary malolactic

fermentation by microorganisms that occur naturally

in these vats. Such organisms may produce beneficial

or detrimental changes in the chemical and organo-

leptic properties of the final cider.

Microbiology of Apple Juice and Cider

0003Freshly pressed apple juice will contain a variety of

yeasts and bacteria, many of which will be incapable

of growth at the acidity of the juice. Examples of

organisms often present in juice are shown in Table 1,

together with an indication of their susceptibility to

sulfur dioxide and ability to grow at the pH of the

juice. (See Microbiology: Detection of Foodborne

Pathogens and their Toxins.)

Role of Sulfur Dioxide in Apple Juice

0004The use of sulfur dioxide as a preservative in cider

making is controlled by legislation, in most countries

the maximum level permitted in the final product

being 200 mg kg

1

.

0005The addition of sulfur dioxide to apple juice results

in the formation of so-called sulfite addition com-

pounds through the binding of sulfite to carbonyl

compounds. The extent of sulfite binding is depend-

ent upon the nature and origin of the carbonyl com-

pounds present in the juice (see below). Similarly, if

sulfur dioxide is added to an actively fermenting

juice, there is a rapid combination with yeast metab-

olites such as acetaldehyde. Such juices will require a

higher quantity of sulfite addition, if wild yeasts and

other microorganisms are to be controlled effectively.

Consequently, all additions of sulfur dioxide must

be completed immediately after pressing the juice,

tbl0001Table 1 Typical microorganisms of freshly pressed apple juice

Type Typicalspecies Ability to

growat the

acidity of

applejuice

a

Sensitivity to

sulfite

b

Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae þþþþ + or

S. uvarum þþþþ + or

Saccharomycodes ludwigii þþþþ

Kloeckeraapiculataþþþþþþþ

Candidamycodermaþþþþ

c

þþþþ

Pichiaspp.þþþþ

c

þþþþ

Torulo p si s f a ma t a þþþþ þþ

Aereobasidium pullulans þþþþ þþþ

Rhodotorulaspp.þþþþþþþþ

BacteriaAcetobacterspp.þþþþ

c

þþ

Pseudomonas spp. þ þþþþ

Escherichia coli /þ þþþþ

Salmonella spp. þþþþ

Micrococcus spp. þ þþþþ

Staphylococcus spp. þ þþþþ

Bacillus spp. (cells) (spores)

Clostridium spp. (cells) (spores)

a

þþþþ, capable of good growth; þ, capable of some growth; /þ, strain-

dependent; , no growth.

b

, insensitive; +, relatively insensitive; þþ, þþþ, þþþþ, increasingly

sensitive.

c

Only in the presence of air (e.g., on the surface of the cider).

1318 CIDER (CYDER; HARD CIDER)/Chemistry and Microbiology of Cidermaking

although, provided the initial fermentation by ‘wild’

yeasts is inhibited, further additions to give a desired

level of free sulfur dioxide can be made during the

following 24h.

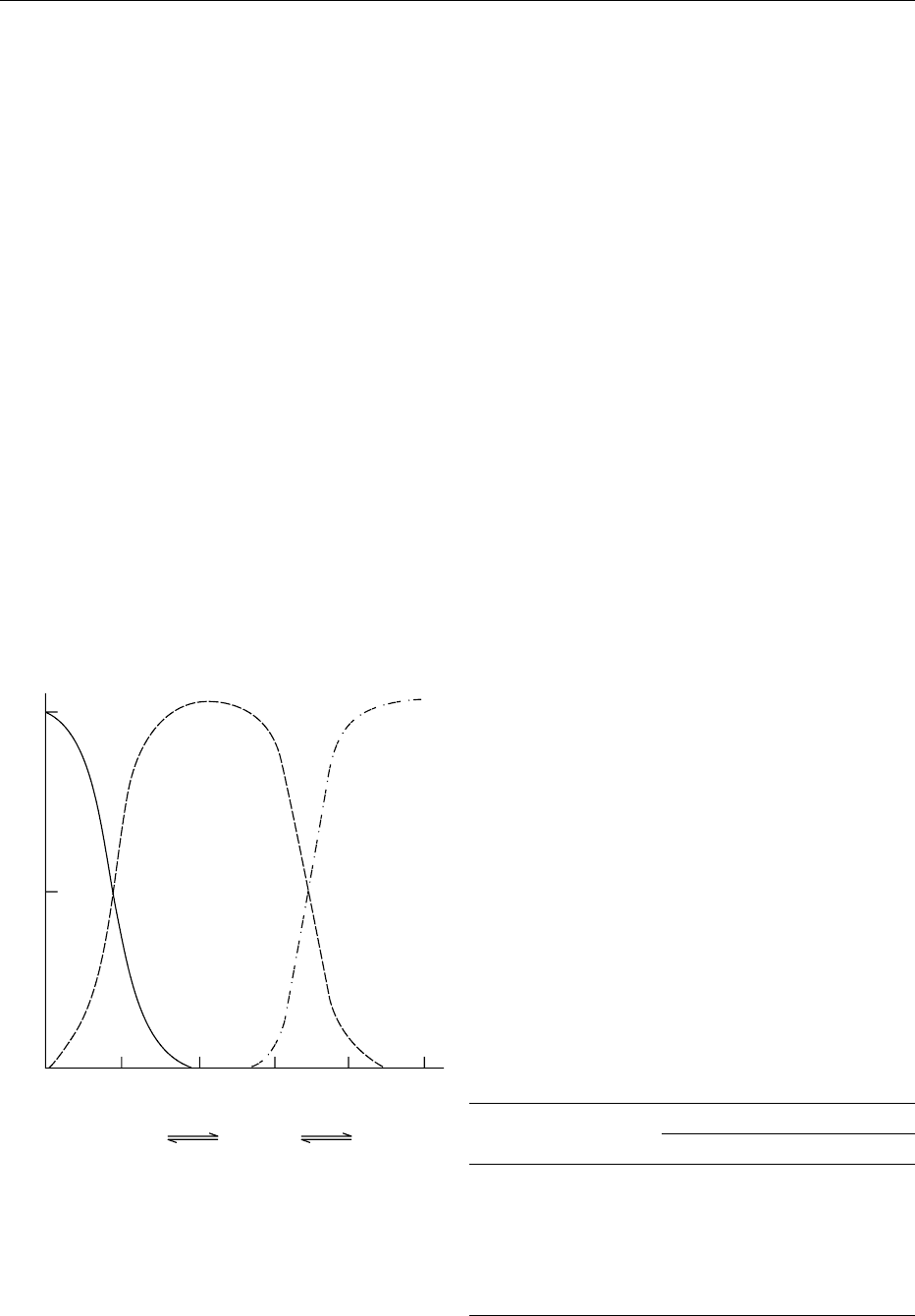

0006 When dissolved in water, sulfur dioxide and its

salts set up a pH-dependent equilibrium mixture of

‘molecular sulfur dioxide,’ bisulfite and sulfite ions

(Figure 1). The antimicrobial activity of sulfur diox-

ide is believed to be due to the molecular sulfur

dioxide moiety of that part which remains unbound

(the so-called ‘free’ sulfur dioxide). Less sulfur diox-

ide is needed in juices of high acidity, for instance

15 mg l

1

of free sulfur dioxide at pH 3.0 has the

same antimicrobial effect as 150 mg l

1

at pH 4.0.

Fermentation Yeasts

0007 The fermentation process is carried out by strains

of Saccharomyces spp., especially S. cerevisiae and

S. uvarum, which are added to the sulfite-treated

juice as a pure culture. The starter culture will be

prepared in the laboratory from freeze-dried or liquid

nitrogen frozen cultures, which are resuscitated in

broth and then cultivated through increasing volumes

of a suitable culture medium to give an inoculum for

use in a starter propagation plant. The nature of the

cultivation medium used will vary but is often based

on sterile apple juice supplemented with appropriate

nitrogenous substrates (e.g., yeast extract) and some-

times with vitamins such as pantothenate and thia-

mine. In order to insure that the starter culture has

both a high viability and a high vitality, it is normal to

aerate the yeast culture during the propagation stage.

0008Increasingly, commercial dried or frozen yeast cell

preparations are used, either for direct vat inocula-

tion or as inocula for the yeast propagation plant. The

availability of such preparations enables the cider

maker to use different strains of yeast for different

cider fermentations without the need to maintain a

wide range of cultures in the laboratory. They also

reduce the risks from mutation and/or contamination

of the starter culture.

0009The choice of culture is dependent upon many

criteria, such as flocculation characteristics, ability

to ferment efficiently at a range of temperatures,

alcohol- and sulfur dioxide tolerance, lack of ability

to produce hydrogen sulfide, etc. One desirable

characteristic is the ability to produce fusel oils (e.g.,

higher alcohols), which affect both the flavor and

aroma of the cider (Table 2).

0010Dependent upon temperature, the fermentation

process typically takes some 10 days to 12 weeks to

proceed to dryness (i.e., specific gravity (SG) 0.990–

1.000) at which time all fermentable sugars will have

been converted to alcohol, carbon dioxide and other

metabolites (Tables 2 and 3). After inoculation, the

starter yeast together with any sulfite-resistant wild

yeasts from the juice will increase in numbers from an

initial level of about 2–5 10

5

colony-forming units

(CFU) ml

1

to 1–5 10

7

CFU ml

1

. Following an

initial aerobic growth phase, the resulting oxygen

limitation and high carbohydrate levels in the media

trigger the onset of the anaerobic fermentation

process.

0011In controlled fermentations, a maximum tempera-

ture of 25

C will generally be tolerated, although

fermentations controlled at 15–18

C are not uncom-

mon in many countries. Because of the exothermic

100

50

0

246810

SO

2

SO

3

2−

HSO

3

−

Percentage of total sulfur dioxide

pH value

Molecular

(SO

2

)

Bisulfite

(HSO

3

)

sulfite

(SO

3

)

−

2−

fig0001 Figure 1 Percentage of sulfite, bisulfite and molecular sulfur

dioxide as a function of pH in aqueous solution. From Hammond

SM and Carr JG (1976) The antimicrobial activity of SO

2

– with

particular reference to fermented and non-fermented fruit juices.

In: Skinner FA and Hugo WB (eds) Inhibition and Inactivation of

Vegetative Microbes (S.A.B. Symposium Series No. 5), pp. 89–110.

London: Academic Press, with permission.

tbl0002Table 2 Higher alcohols in apple juices and ciders

Concentration range (mg l

1

)

Applejuices Ciders

n-Propanol 0.2–2 4–200

n-Butanol 3–24 4–32

iso-Butanol 14–74

iso-Pentanol 0.1 42–196

sec-Pentanol 0.1–2 16–39

n-Hexanol 1–2 2–17

2-Phenylethanol 7–260

CIDER (CYDER; HARD CIDER)/Chemistry and Microbiology of Cidermaking 1319

nature of the initial stages of fermentation, it is

normal to cool the fermentation base to a tempera-

ture < 18

C prior to inoculation, otherwise excessive

temperatures (30

C or above) can be reached. In

tropical countries, it is not uncommon for tempera-

tures as high as 35–40

C to occur in the fermentation

vat in the absence of effective temperature control.

0012 Such high temperatures are undesirable since

activity of the starter yeast strain may be inhibited –

leading to ‘stuck’ fermentations and the growth of

undesirable thermoduric yeasts and spoilage bacteria.

Stuck fermentations can sometimes be restarted by

‘rousing’ (bubbling carbon dioxide through the vat),

and/or addition of glucose, a nitrogen source (10–

50 mg l

1

), usually diammonium phosphate, and thia-

mine (0.1–0.2 mg l

1

); yeast ‘hulls’ may also be added.

0013 At the end of fermentation, the yeast cells will

flocculate and settle to the bottom of the vat. During

this process, a certain amount of cell autolysis occurs,

which liberates cell constituents into the cider. The

raw cider will be drawn (racked) off the lees as

a cloudy product and transferred to storage vats

for maturation. In some plants, the cider may be

centrifuged or rough filtered at this time. If the cider

is left too long on the lees, the extent of autolysis may

become excessive leading to a build-up of nitrogenous

materials that will act as substrates for subsequent

undesirable microbial growth and the development

of off-flavors in the product. (See Yeasts.)

Maturation and Secondary Fermentation

0014 The maturation vats are filled with the racked-off

cider and either provided with an ‘over-blanket’ of

carbon dioxide or sealed to prevent ingress of air,

which would stimulate the growth of film-forming

yeasts (e.g., Brettanomyces spp., Pichia membrane-

faciens, Candida mycoderma) and aerobic bacteria

(e.g., Acetobacter xylinum). Growth of such yeasts

will produce precursors of an unpleasant flavor

compound, believed to be 1,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2-

aceto-pyridine, which is responsible for a ‘mousey’

flavor defect. Growth of Acetobacter spp. will pro-

duce acetic and other volatile acids, which impart a

vinegary note. Of course, deliberate acetification of

cider can be used to produce cider vinegar.

0015 During the maturation process, growth of lactic

acid bacteria (LAB) (e.g., Lactobacillus pastorianus

var. quinicus, L. mali, L. plantarum, Leuconostoc

mesenteroides, etc.) causes a malolactic fermentation

(see below). (See Lactic Acid Bacteria.)

Spoilage and Other Microorganisms in Cider

0016 Bacterial pathogens, such as Salmonella spp., Esc-

herichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus, may

occasionally occur in apple juice, having been derived

from the orchard soil, farm, and factory process

equipment or human sources. Normally, the acidity

of the product prevents growth, and such organisms

do not survive for long in the fermenting product. In

recent years, there have been several reports of food

poisoning in the USA due to E. coli O157:H7 in ‘cider’.

These references to ‘cider’ refer not to fermented (or

‘hard’ cider) but to fresh pressed apple juice. It has been

established that although these highly acid-tolerant

strains of E. coli, associated with the US outbreaks,

can survive for long periods, and may even grow, in

apple juice, they are extremely sensitive to alcohol and

die within 1–2 h in fermenting cider.

0017In 1994, a report of a serious outbreak of crypto-

sporidiosis in the USA from consumption of ‘cider’

was again associated with freshly pressed apple juice,

not fermented cider. However, the report highlights a

potential risk of contamination of apples, juice and

cider by oocysts of Cryptosporidium spp. if apples are

harvested from an orchard sward following grazing

by animals. Crytosporidium oocysts are sensitive to

pasteurization; furthermore, the filtration processes

used in commercial cider production would remove

any contaminant oocysts.

0018Bacterial spores from species of Bacillus and

Clostridium can survive for long periods and are

frequently found in cider but do not create a spoilage

threat, because of the acidity, although their presence

may be indicative of poor plant hygiene.

0019The juice from unsound fruits and juice contamin-

ated within the process plant may show extensive

contamination by microfungi, such as Penicillium

expansum, P. crustosum, Aspergillus niger, A. nidu-

lans, A. fumigatus, Paecilomyces varioti, Byssochla-

mys fulva, Monascus ruber, Phialophora mustea, and

by species of Alternaria, Cladosporium, Botrytis,

Oospora,andFusarium. None are of particular direct

concern in cider making, except that heat-resistant

species (e.g., Byssochlamys spp.) can survive pasteur-

ization and grow in cider if it is not adequately

carbonated. (See Microbiology: Classification of

Microorganisms; Food Poisoning: Classification.)

0020The occurrence of the mycotoxin ‘patulin’ in apples

infected with Penicillium expansum may result in

carry-over of patulin in the apple juice base used for

cider fermentation. Although patulin initially inhibits

growth of the fermentation yeasts, the organisms rap-

idly become tolerant to patulin, and once growth is

initiated, the patulin is rapidly metabolized to form

ascladiol and smaller amounts of other metabolites.

Hence, if apple juice is contaminated with patulin, the

fermentation may be slow to start, but the patulin will

be destroyed within a few hours. Claims from France

that patulin has been found in fermented cider are

1320 CIDER (CYDER; HARD CIDER)/Chemistry and Microbiology of Cidermaking

believed to be associated with post-fermentation

sweetening of the cider by addition of patulin-con-

taminated apple juice. (See Mycotoxins: Occurrence

and Determination; Toxicology.)

0021 In addition to Brettanomyces spp. and Acetobacter

spp., which can cause oxidative spoilage of cider

during fermentation and maturation, the yeast

Saccharomycodes ludwigii can be a major spoilage

organism. Sacc. ludwigii, which is often resistant to

sulfite levels as high as 1000–1500 mg l

1

, can grow

slowly during all stages of fermentation and matur-

ation and is often an indigenous contaminant of cider-

making premises. Its presence in bulk stocks of cider

does not cause overt problems. However, if it is able

to contaminate ‘bright’ cider at bottling, its growth

will result in a butyric flavor and the presence of flaky

particles that spoil the appearance of the product.

Although the organism is sensitive to pasteurization,

it is not unknown for it to contaminate products at

the packaging stage, either as a low level contaminant

of clean but nonsterile bottles or from the packaging

plant and its environment.

0022 Environmental contamination of final products

can occur also with wild strains of yeasts such as

S. cerevisiae, Zygosaccharomyas bailii, and S.

uvarum, which will metabolize any residual or

added sugar to generate further alcohol and, more

importantly, to increase the concentration of carbon

dioxide. Process-plant strains of these organisms are

frequently resistant to low levels of sulfite. In bottles

of cider inoculated with such fermentative organisms,

carbonation pressures of up to 9 bar have been

recorded. For this reason, it is essential to maintain

an adequate level of free sulfite (typically 30–50 mg

l

1

) in the final product, particularly in multiserve

containers that may be opened and then stored with

a reduced volume of cider; alternatively, a second

preservative such as benzoic or sorbic acid can be

used, where permitted by legislation. This precaution

is not necessary for products packaged in single-serve

cans and small bottles that are in-pack pasteurized

after filling.

Special Secondary Fermentation Processes

0023 Conditioned draught cider Traditional ‘condi-

tioned’ draught cider results from a live secondary

fermentation process. After filling into barrels, a

small quantity of fermentable carbohydrate is added

to the cider, followed by an active inoculum of

alcohol-resistant yeasts. The subsequent growth is

accompanied by a low-level fermentation, during

which sufficient carbon dioxide is generated to pro-

duce a ‘pettilance’ in the cider together with a haze of

yeast cells. Such products have a relatively short shelf-

life in the barrel.

0024Double fermented cider The cider is initially fer-

mented to a lower than normal alcohol content

(e.g., 5% abv) by restricting the total amount of

sugar present. The liquor is racked off as soon as the

cider has fermented to dryness and either sterile-

filtered or pasteurized prior to transfer to a second

sterile fermentation vat. Fermentation sugar and/or

apple juice is added, and a secondary fermentation

is induced following inoculation with an alcohol-

tolerant strain of Saccharomyces spp. Such a process

permits the development of very complex flavors in

the cider.

0025Sparkling ciders Sparkling ciders are normally pre-

pared nowadays by artificial carbonation to a pres-

sure of 3.5–4 bar. Traditionally, sparkling ciders were

prepared according to the ‘methode champagnoise.’

After bright filtration, the fully fermented dry cider is

filled into bottles containing a small amount of sugar

and an appropriate Champagne yeast culture. The

bottles are corked and wired and laid on their side

for the fermentation process, which will last from

1 to 2 months at 15–18

C. Following this stage, the

bottles are placed in special racks with the neck in a

downwards position. The bottles are gently shaken

each day to move the deposit down towards the cork,

a process that can take up to 2 months. The disgor-

ging process involves careful removal of the cork and

yeast floc but without loss of any liquid (sometimes

the neck of the bottle is frozen to aid this process).

The disgorged product is then topped up using a

syrup of alcohol, cider, and sugar prior to final

corking, wiring, and labeling. It is not difficult to

understand why this process is rarely used nowadays!

An alternative process, known as ‘cuve

´

e close,’

involves a secondary fermentation using champagne

yeast in a sealed vat. The naturally produced carbon

dioxide is retained in the cider, which is filtered and

bottled under a positive pressure.

Chemistry of Cider

0026The chemical composition of cider is dependent upon

the composition of the apple juice, the nature of the

fermentation yeasts, malolactic bacteria, microbial

contaminants, and their metabolites, and the nature

of any additives used in the final product.

Composition of Cider Apple Juice

0027Apple juice is a mixture of sugars (primarily fructose,

glucose, and sucrose), oligosaccharides, and polysa-

charides (e.g., starch) together with malic, quinic, and

citromalic acids, tannins (i.e., polyphenols), amides

and other nitrogenous compounds, soluble pectin,

vitamin C, minerals, and a diverse range of esters

CIDER (CYDER; HARD CIDER)/Chemistry and Microbiology of Cidermaking 1321

that give the juice a typical apple-like aroma (e.g.,

ethyl- and methyl-iso-valerate). The relative propor-

tions will be dependent upon the variety of apple, the

cultural conditions under which it was grown, the

state of maturity of the fruit at the time of pressing,

the extent of physical and biological damage (e.g.,

mold rots), and, to a lesser extent, the efficiency

with which the juice was pressed from the fruit.

0028 Treatment of the fresh juice and/or cider with sul-

fite results in the complexing of carbonyl compounds

to form stable hydroxy sulfonic acids. If the apples

contained a high proportion of mold rots, then appre-

ciable amounts of carbonyls such as 2,5-dioxogluco-

nic acid and 2,5-d-threo-hexodiulose will occur,

which bind sulfite effectively. Sulfite-binding also

occurs with sugars, such as glucose and xylose, and

with yeast metabolites such as acetaldehyde and

pyruvate. Sulfur dioxide is important also as an

antioxidant that prevents enzymic and nonenzymic

browning reactions of the polyphenols.

Products of the Fermentation Process

0029 The primary objective of fermentation is the produc-

tion of ethyl alcohol from fruit sugars with the asso-

ciated formation of carbon dioxide. The biochemical

pathways that govern this process are well recognized

(Embden–Meyerhof–Parnass pathway).

0030 The various intermediates in this metabolic path-

way can also be converted to form a diverse range of

other metabolites, including glycerol (up to 0.5%).

Diacetyl and acetaldehyde may also occur, particu-

larly if the conversion of pyruvate to ethanol is in-

hibited by excess sulfite and/or if uncontrolled lactic

fermentation occurs. Other metabolic pathways

operate simultaneously with the formation of long-

and short-chain fatty acids, esters, lactones, etc.

Methanol will be produced in small quantities

(10–100 mg l

1

) as a result of demethylation of pectin

in the juice. Table 3 illustrates some of the volatile

compounds found in a normal and spoiled cider

blend.

0031 If LAB are also present in the fermentation, these

can convert malic and quinic acids to lactic and dihy-

droshikimic acids, respectively, thereby reducing the

acidity of the cider. These reactions are accompanied

by further diverse, but not widely understood, chem-

ical and biochemical changes that result in subtle, yet

important, flavor changes in the final product. Lactic

and acetic acids can also be formed by metabolism of

residual sugars and ethanol; great care needs to be

taken to avoid excessive production of volatile acids

in cider.

0032 It has long been believed that most tannins in cider

do not change significantly during fermentation,

other than the reduction of the chlorogenic, caffeic

and p-coumaryl quinic acids to dihydroshikimic acid

and ethyl catechol, respectively. However, recent work

has shown that several other very important quanti-

tative and qualitative changes occur, especially during

the malolactic fermentation. Such changes modify the

organoleptic perception of bitterness and astringency

in cider.

0033The nitrogen content of cider juice includes a range

of amino acids, the most important of which are

asparagine, aspartic acid, glutamine, and glutamic

acid; small amounts of proline and 4-hydroxy-

methyl-proline also occur. Aromatic amino acids

are virtually absent from apple juices. With the ex-

ception of proline and 4-hydroxy-methyl-proline, the

amino acids are largely assimilated by the yeasts

tbl0003Table 3 Volatile compounds in a normal and a diacetyl-spoiled

cider

Compound Normalizedpeak area

a

Normal cider Spoiled cider

Ethyl acetate 86.1 89.2

Diacetyl 0 3.4

Ethyl-2-methylbutyrate 10.3 12.9

2-Methylpropanol 35.4 97.3

iso-Amyl alcohol 305 213

2- and 3-Methyl-butan-1-ol 503 456

Ethyl hexanoate 233 179

Hexyl acetate 2 6.3

Octanol 0.7 1.2

Ethyl lactate 45.9 37.9

Hexan-1-ol 35.7 29.5

Nonanol 0.8 0.9

Unknown ester or acetal

(relative molecular mass 172)

25.6 77.7

Ethyl octanoate 280 226

Heptan-1-ol 1.3 0.8

Ethyl octanoate 3.4 11.5

Decan-2-one 3.6 0.9

Benzalaldehyde 1.4 1.4

Ethyl-2-hydroxy-4-methyl

pentanoate

4.2 7

Ethyl decanoate 57.6 53.4

Decanal 7.5 0.4

Ethyl benzoate 4.7 5.7

Diethyl succinate 5.2 2.9

Unknown ester 3.2 4.9

Methionol 1.3 0.6

Undecanal 2.2 1.2

2-Phenylethyl acetate 11.4 6.4

Hexanoic acid 12.6 12.6

Ethyl dodecanate 2.1 1

2-Phenylethanol 69 61.6

Heptanoic acid 0 3.4

d-Decalactone 4.4 3.4

Ethyl guaiacol 2.5 4.5

Octanoic acid 34.6 29.4

Nonanoic acid 1 1.2

a

Based on gas chromatography–mass spectroscopy analysis of

headspace volatiles.

1322 CIDER (CYDER; HARD CIDER)/Chemistry and Microbiology of Cidermaking

during fermentation. However, leaving the cider on

the lees for an appreciable length of time will signifi-

cantly increase the amino nitrogen content as a con-

sequence of the release of cell constituents during

autolysis.

0034 Inorganic compounds in cider are derived largely

from the fruit and will depend upon the conditions

prevailing in the orchard. These levels do not change

significantly during fermentation. Small amounts of

iron and copper may occur naturally, but the presence

of more than a few milligrams per liter will result in

significant black or green discolorations and flavor

deterioration. The discolorations are due to the for-

mation of iron or copper tannates from traces of

metal ions derived from equipment and/or from the

use of rotten fruit.

Cider Maturation

0035 The aroma and flavor of freshly fermented cider are

quite harsh. During maturation, significant changes

occur in the composition of the cider that are due to

microbial and biochemical activity, producing diverse

compositional changes. More than 200 metabolites

have been identified in mature cider; some produce

desirable aroma and flavor characteristics, whereas

others may be responsible for undesirable character-

istics, especially if present in excessive amounts. The

‘malolactic fermentation’ causes a reduction in the

acidity of the cider and imparts subtle flavor changes

that generally improve the flavor. Much of the lactic

acid, produced by decarboxylation of malic acid, is

esterified with the formation of ethyl-lactate and

other esters, which impart a smooth ‘creamy’ flavor

to the product. Malolactic fermentation also results

in the production of important volatile metabolites

such as 1-hexanol, 2- and 3-methyl-butanol, and

2-phenyl-ethanol. The occurrence in mature cider of

a compound with molecular mass 172 has been at-

tributed variously to the occurrence of 1-ethoxyoct-5-

en-1-ol, ethenylthio-octane, 5-chloro-salicylic, and

other metabolites. It has been suggested that this

compound may be responsible for the typical ‘cider’

flavor and aroma. Changes to the polyphenols

(tannins) result in subtle changes to the perception

of astringency and bitter characteristics.

0036 However, in certain circumstances, metabolites

of the lactic acid bacteria may damage the flavor

and result in spoilage, e.g., excessive production of

diacetyl (and its vicinyl-diketone precursors), the

‘butterscotch-like’ taste of which can be detected in

cider at a threshold level of about 0.6 mg l

1

.

Commercial Ciders

0037A final blending of ciders is made to attain specific

characteristics of sweetness, dryness, alcohol content,

flavor, and aroma. Sugars or intense sweeteners, such

as saccharin (which increases the perception of asrin-

gency), may be added. Artificial colors, ascorbic acid

(as an antioxidant), and additional chemical preser-

vatives (e.g., sulfur dioxide or sorbic acid) may also

be added. Prior to final packaging, the cider is car-

bonated to give the product a petillance or sparkle.

See also: Cider (Cyder; Hard Cider): The Product and its

Manufacture; Lactic Acid Bacteria; Mycotoxins:

Classifications; Preservatives: Classifications and

Properties; Spoilage: Bacterial Spoilage; Yeasts in

Spoilage; Tannins and Polyphenols; Yeasts

Further Reading

Beech FW (1972) English cidermaking: technology, micro-

biology and biochemistry. In: Hockenhull DJD (ed.)

Progress in Industrial Microbiology, vol. 11, pp.

133–213. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Beech FW and Davenport RR (1983) New prospects and

problems in the beverage industry. In: Roberts TA and

Skinner FA (eds.) Food Microbiology: Advances and

Prospects (S.A.B. Symposium Series No. 11), pp.

241–256. London: Academic Press.

Charley VLS (1949) The Principles and Practice of Cider-

making. London: Leonard Hill.

Hammond SM and Carr JG (1976) The antimicrobial

activity of SO

2

– with particular reference to fermented

and non-fermented fruit juices. In: Skinner FA, Hugo WB

(eds) Inhibition and Inactivation of Vegetative Microbes

(S.A.B. Symposium Series No. 5), pp. 89–110. London:

Academic Press.

Jarvis B (2001) Cider, perry, fruit wines and other alcoholic

beverages. In: Arthey D and Ashurst PR (eds) Fruit Pro-

cessing, 2nd edn. pp. 111–148. Gaithersburg, MA:

Aspen Publishers Inc.

Jarvis B, Forster MJ and Kinsella WP (1995) Factors

affecting the development of cider flavour. In: Board

RG, Jones D and Jarvis B (eds) Microbial Fermentations:

Beverages, Foods and Feeds (SAB Symposium Series No.

24). Journal of Applied Bacteriology 79(supplement):

5S–18S.

Jarvis B and Lea AGH (2000) Sulphite binding in ciders.

International Journal of Food Science and Technology

35: 113–127.

Lea AGH (1995) Cidermaking. In: Lea AGH and Piggott JR

(eds.) Fermented Beverage Production, pp. 66–96.

London: Blackie Academic & Professional.

Williams RR (ed.) (1991) Cider and Juice Apples: Growing

and Processing. Bristol: University of Bristol.

CIDER (CYDER; HARD CIDER)/Chemistry and Microbiology of Cidermaking 1323

CIRRHOSIS AND DISORDERS OF HIGH

ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION

I Bitsch, Institut fu

¨

r Erna

¨

hrungswissenschaft der

Justus-Liebig Universit, Giessen, Germany

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 It is well documented that heavy drinking of alcoholic

beverages carries an increased risk of morbidity and

mortality from diseases affecting many organs and

may lead to psychic and physical dependence on

alcohol. The risks depend on the amount of alcohol

consumed, the drinking pattern, and the individual

sensitivity. For these reasons, no generally valid

threshold value for safe alcohol consumption can be

given. Most authors agree that an upper limit of 80 g

of ethanol per day should not be exceeded. A moder-

ate drinker is considered as one who consumes 5–25 g

of ethanol per day and a light drinker as one who

consumes 0.2–5 g per day. Definitions of moderate

drinking vary among studies. The US Department of

Agriculture and the US Department of Health and

Human Services define moderate drinking as not

more than 24 g pure alcohol per day for men and

not more than 12 g per day for women. Women

appear to be more vulnerable than men to many

adverse consequences of alcohol use. Women achieve

higher concentrations of alcohol in the blood and

become more impaired than men after drinking

equivalent amounts of alcohol. Research also sug-

gests that women are more susceptible than men to

alcohol-related organ damage. Compared with men,

women develop alcohol-induced liver disease over a

shorter period of time and after consuming less alco-

hol. In addition women are more likely than men to

develop alcoholic hepatitis and to die from cirrhosis.

Alcoholism

0002 Three main patterns of chronic alcohol abuse are

described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric

Association (1994):

.

0003 regular drinking of large amounts

.

0004 regular heavy drinking but limited to weekends

.

0005 episodic bingesof heavydaily drinkinglasting weeks

or months, interrupted by long periods of sobriety

0006 These criteria for the diagnosis of alcoholism also

include an impairment in social or occupational

functioning. Alcoholism is further distinguished

from alcohol abuse by tolerance and physical depend-

ence. Tolerance is defined as the ‘need for markedly

increased amounts of alcohol to achieve the desired

effect, or a markedly diminished effect with regular

use of the same amount.’ Dependence is defined as

‘the development of alcohol withdrawal syndrome

after cessation of or reduction in drinking.’ (See Alco-

hol: Metabolism, Beneficial Effects, and Toxicology;

Alcohol: Alcohol Consumption.)

0007Excessive alcohol intake is often associated with

malnutrition. This results from the limited intake of

nutritionally adequate foods and from the impairment

of digestion, absorption, transport, storage, metabol-

ism, and excretion of many nutrients by direct or

indirect action of ethanol. The role of nutrient defi-

ciencies in the initiation and progression of the med-

ical complications of alcoholism is still controversial.

0008Protein malnutrition (kwashiorkor-like) and pro-

tein-energy malnutrition (marasmus-like) are fre-

quent in alcoholic patients with liver disease and, in

some studies, the prevalence of the malnutrition cor-

relates closely with the severity of organ failure. On

the other hand, many patients who drink to excess are

clearly not protein-energy-malnourished. Ethanol has

appreciable effects on amino acid metabolism. Intes-

tinal absorption and transport of isoleucine, arginine,

and methionine are impaired by high concentrations

of ethanol. Branched-chain amino acids and a-amino-

N-butyric acid are increased in the plasma of alcohol-

ics. (See Protein: Deficiency.)

0009Vitamin deficiencies are frequent in alcoholics and

especially in those with liver disease. Most common is

an insufficient folate supply, characterized by mega-

loblastic anemia and macrocytosis of the intestinal

epithelium. Many factors contribute to folate defi-

ciency in alcoholics. These include dietary deficiency,

intestinal malabsorption, impairment of uptake and/

or storage in the liver, and increased urinary excre-

tion. Also ethanol metabolism perturbs folate metab-

olism through inhibition of methionine synthase,

resulting in dysregulation of nucleotides and en-

hanced cancer risk. Also, the acetaldehyde product

of ethanol metabolism was shown in vitro to trigger

oxidative catabolism of the folic acid molecule. Poor

dietary intake is undoubtedly the major cause, with

the exception of heavy beer drinkers: 2 l of beer con-

tain nearly 50% of the recommended daily allowance

of folate for an adult man. The combined effect of

low folate concentration in the diet and heavy alcohol

1324 CIRRHOSIS AND DISORDERS OF HIGH ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION

drinking leads to damage of intestinal mucosal epi-

thelial structures, often associated with diarrhea,

and results in malabsorption of folates and other

nutrients. Symptoms of vitamin B

12

deficiency are

much less common than those of folate deficiency in

alcoholics. This is probably attributable to the large

stores of vitamin B

12

in the body and the reserve

capacity for absorption. In most studies the circulat-

ing levels of vitamin B

12

in alcoholics are not different

from normal controls. (See Cobalamins: Physiology;

Folic Acid: Physiology.)

0010 As with folate, poor dietary intake and an impair-

ment of absorption are the main causes for insuffi-

cient thiamin supply in alcoholics. Alcohol inhibits

active transport of thiamin across the intestinal

mucosa, due to inhibition of Na,K-ATPase at the

basolateral membrane of enterocyte, whereas the pas-

sive transport remains unimpaired. In addition, hep-

atic storage of thiamin may be reduced owing to fatty

infiltration of the liver, hepatocellular damage, or

cirrhosis in chronic alcoholic patients. Extreme thia-

min deficiency is responsible for the Wernicke–

Korsakoff syndrome, beriberi, and polyneuropathy

in alcoholics. (See Thiamin: Physiology.)

0011 The incidence of pyridoxine deficiency in alcoholic

patients, as defined by low plasma levels of its circu-

lating form, pyridoxal-5-phosphate (PLP), is more

than 50% in different studies. Clinical data indicate

that malnutrition, rather than the amount and dur-

ation of alcohol abuse, is the major determinant of

pyridoxine deficiency. Pyridoxine absorption is pri-

marily passive and is affected only by very high con-

centrations of ethanol. PLP in erythrocytes and liver

is more rapidly destroyed in the presence of acetalde-

hyde, the first metabolite of ethanol oxidation, per-

haps by displacement of PLP from protein and its

exposure to phosphatases. This results in high pyri-

doxic acid excretion in the urine. Clinical signs of

pyridoxine deficiency in alcoholics are infrequent.

Sideroblastic bone marrow changes often occur in

alcoholics with low plasma PLP values, but most of

these patients also suffer from liver disease and folate

deficiency. (See Vitamin B

6

: Properties and Determin-

ation.)

0012 Studies of vitamin A deficiency in alcoholism have

mainly concerned patients with established cirrhosis,

who may have impaired storage or transport of vita-

min A because of an inadequate synthesis of retinol-

binding protein. Most of them also have inadequate

dietary intake. Other complications of alcoholism,

e.g., pancreatic and biliary insufficiency, lead to mal-

absorption of vitamin A because this fat-soluble vita-

min requires for its absorption adequate quantities of

pancreatic lipases and bile salts in the small intestine.

Another possible mechanism for low hepatic vitamin

A level is increased hepatic metabolism of retinoic

acid to polar metabolites through the action of micro-

somal enzymes, which are inducible by ethanol con-

sumption. The clinical consequences of insufficient

vitamin A supply in alcoholics are increased incidence

of night blindness, follicular keratosis, and corneal

ulcerations. Vitamin A deficiency may compromise

immune function and may be procarcinogenic through

effects on epithelial cell metaplasia in the orophar-

ynx. Alcoholics with these complications often re-

quire both vitamin A and zinc treatment to correct

visual dysfunction, because of an association between

zinc and vitamin A metabolism. Zinc is an essential

cofactor in the conversion of retinol to retinaldehyde

in the retina. Alcohol appears to stimulate the release

of zinc from hepatic stores, and its urinary excretion.

Zinc levels in plasma and red blood cells are often

reduced in humans after chronic alcohol ingestion.

Also zinc pools are redistributed with greater tissue

binding in response to various cytokine mediators of

alcoholic liver injury. The potential consequences of

zinc deficiency include acrodermatitis, altered taste

and smell, and night blindness. (See Retinol: Physi-

ology; Zinc: Physiology.)

0013Vitamin D intake, absorption, and metabolism

seem to be impaired in alcoholics, and there are ab-

normalities of phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium

homeostasis. Alcoholic patients often suffer from

decreased bone mass and an increased incidence of

fractures. (See Calcium: Physiology; Cholecalciferol:

Physiology; Magnesium.)

Alcoholic Cirrhosis

0014Alcohol is the most common cause of cirrhosis in

western countries. The incidence of this disease in

alcoholics depends upon the mean daily intake of

alcohol and the mean duration of alcohol consump-

tion. However, only about 20% of heavy drinkers

develop cirrhosis, and liver disease may progress to

cirrhosis after cessation of ethanol ingestion. This fact

suggests that other factors superimposed on alcohol

drinking are involved in the pathogenesis of this

severe form of liver injury. These include gender,

genetic or immunological variables, other hepatotox-

ins, nutrition, viral hepatitis, and others. Individual

predisposition is an important physiological factor

in the development of this disease. Understanding

the mechanism of the differences in susceptibility to

cirrhosis may help clinicians to identify and treat

patients at increased risk. (See Liver: Nutritional

Management of Liver and Biliary Disorders.)

0015Morphologically, cirrhosis of the liver is a diffuse

process, characterized by an excessive proliferation of

connective tissue and the deposition of structurally

CIRRHOSIS AND DISORDERS OF HIGH ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION 1325