Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

produced in net shape or near-net shape. Even fairly

complicated shapes may be involved, as in injection

molding. Another advantage is their superior mechan-

ical properties. Bonded magnets are mainly manufac-

tured from ferrite powder or coercive NdFeB-based

powders. Bonded magnets based on NdFeB, owing to

their superior intrinsic magnetic properties, offer sub-

stantial advantages in terms of size, weight, and per-

formance over bonded ferrite magnets and even over

sintered ferrite magnets.

2. The Permanent Magnet Materials

The most common types of magnets used at present

are hard ferrite magnets, rare earth-based magnets

such as SmCo or NdFeB, and alnico-type magnets.

Of these the alnico magnets have only a modest co-

ercivity which leads to nonlinear demagnetization

characteristics. For this reason their applicability is

very limited compared with the other two types. The

hard ferrites have higher coercivities than the alnico

magnets and their demagnetizing characteristics are

linear. However, the remanence and the concomitant

maximum energy product are already low and are

further decreased by bonding. Because of their low

cost, ferrite magnets are still widely applied, al-

though most of the corresponding magnetic devices

are rather bulky and often give far from optimal

performance. Ferrite permanent magnets currently

dominate automotive and many other applications

due to their low cost and proven long-term stability

(see Alnicos and Hexaferrites).

The rare earth based magnets have high values of

coercivity which gives them linear demagnetization

characteristics (see Rare Earth Magnets: Materials).

They have high remanences and typical values of the

energy products reached in sintered magnets are 150

kJ m

3

for SmCo

5

, and 300 kJ m

3

for Nd

2

Fe

14

B.

The first types of magnets are frequently used in high-

temperature applications, which possibility is lost in

bonded magnets (see Magnets: High-temperature).

SmCo

5

type magnets are expensive owing to the high

price of both samarium and cobalt. The situation is

more favorable for NdFeB magnets because neo-

dymium is cheaper than samarium and iron is much

cheaper than cobalt, the powder metallurgical

processing arts being comparable with those of

SmCo

5

. Hence the performance/price ratio for

Nd

2

Fe

14

B is better than for SmCo

5

. For this reason

the market for sintered Nd

2

Fe

14

B magnets has flour-

ished and is still growing (see Magnets: Sintered).

Although bonded magnets can be manufactured

from all of the materials mentioned above, only

bonded ferrite magnets and bonded Nd

2

Fe

14

B mag-

nets have penetrated into the market to an appreci-

able extent. The ferrites can be easily obtained in

powder form (see Alnicos and Hexaferrites). A some-

what special processing of the ferrite powders leads to

hexagonal platelets that can be easily aligned me-

chanically during the formation process of flexible

bonded magnets. The situation is more difficult in the

case of Nd

2

Fe

14

B, because a simple powder metal-

lurgical route from cast or annealed Nd

2

Fe

14

B ingots

does not generally lead to powders of sufficiently high

coercivity for use in bonded magnets. Coercive

NdFeB powders can be obtained though by melt

spinning. In this technique a fine stream of molten

alloy is sprayed onto the outer surface of a rapidly

spinning wheel, leading to thin rapidly quenched rib-

bons or flakes. During the melt spinning the material

is protected from oxidation by performing this proc-

ess in a protective atmosphere or in vacuum. The

quenching rate is of the order of 10

5

Ks

1

and can be

varied by changing the rotational speed of the spin-

ning wheel. Different quenching rates lead to differ-

ent microstructures which in turn determine the

magnetic properties of the melt spun material. Opti-

mum melt spinning conditions lead to a nanocrystal-

line alloy consisting of fine grains (typically 30 nm) of

the compound Nd

2

Fe

14

B, surrounded by a thin layer

of a neodymium-rich eutectic phase. In practice,

more reliable and reproducible results can be ob-

tained by using a slightly higher quenching rate and

subsequently annealing the melt spun material under

carefully controlled conditions. The melt spun mate-

rial is fairly brittle and can be ground to a fine pow-

der suitable for manufacturing bonded magnets.

Because the Nd

2

Fe

14

B grains have a random orien-

tation, these bonded magnets are isotropic. Powder

particles of spherical shape flow better in the injection

molding process, which allows a higher loading fac-

tor. Such powder can be prepared by an inert gas

atomization process with typical values for the mean

particle diameter of 45 mm. An additional advantage

of the atomization process is the high production rate

and low processing costs of the powders (Ma et al.

2002).

A different route leading to coercive NdFeB pow-

ders consists of the so-called HDDR process (see

Magnets: HDDR Processed). This process involves

essentially four steps: hydrogenation of Nd

2

Fe

14

Bat

low temperatures, decomposition of Nd

2

Fe

14

BH

x

in-

to NdH

2.7

þFe þFe

2

B, desorption of H

2

gas from

NdH

2.7

, and recombination of Nd þFe þFe

2

B into

Nd

2

Fe

14

B. This process profits from the fact that the

formation of Nd

2

Fe

14

B grains in the last step is a

solid-state reaction and hence proceeds at a rate con-

siderably lower than during solidification from the

melt during a normal casting process. The average

Nd

2

Fe

14

B grain size remains in the nanometer range

and gives rise to sufficiently large coercivities.

A further advantage is the fact that the HDDR

process can successfully be used to obtain anisotropic

particles. Takeshita and Nakayama (1992) discovered

that additives of zirconium, hafnium, and gallium, in

particular, are very effective in producing anisotropic

HDDR powder. The amount of additive required is

860

Magnets: Bon ded Permanent Magnets

surprisingly small (for instance, Nd

12.5

Fe

69.9

Co

11.5

B

6

Zr

0.1

). Microscopic investigations described by

Harris (1992) revealed that large facetted HDDR

grains had formed within the original as-cast grain of

the alloy. These facetted grains have a common ori-

entation, which is probably the same as that of the

original grain. The anisotropic nature of HDDR

powders of alloys like Nd

12.5

Fe

75.9

Co

11.5

B

8

Zr

0.1

can

thus be visualized by assuming that the HDDR

grains have nucleated and grown within an original

as-cast grain region from submicron grains, the latter

having a common orientation (Harris 1992).

Evidently the effect of the additive is to bring about

nucleation centers for nucleation and growth of the

HDDR grains, the latter grains having kept the ori-

entation of the original cast grain.

Tomida et al. (1996) have used x-ray diffraction to

establish a correlation between the anisotropic nature

of the ultimate HDDR powder and the amount of

Nd

2

Fe

14

B phase remaining unreacted in the hydro-

genation process. TEM studies made by Tomida

et al. on powder hydrogenated under optimum ener-

gy product conditions showed that after hydrogena-

tion the powder consists mainly of coarse-grained

a-Fe and Fe

2

B, with nanocrystalline particles embed-

ded in between. These particles were identified by

electron diffraction as NdH

2

particles. However,

many of the particles were identified as Nd

2

Fe

14

B

particles having a crystallographical orientation al-

most the same as that of the original cast Nd

2

Fe

14

B

grains. Energy-dispersive spectra furthermore

showed that these particles are of higher cobalt and

gallium concentration than corresponding to the av-

erage concentration of the starting alloy. These re-

sults have led Tomida et al. to propose that this type

of nanocrystalline Nd

2

Fe

14

B particles serve as initi-

ation centers in the recombination process and are

the origin of the orientational memory effect in

HDDR powders.

A different category of materials that appears to be

promising is nanocrystalline rare earth-based com-

posite magnets. Under special circumstances, two-

phase composite materials can demonstrate a most

interesting coercivity behavior. Such a behavior has

been described by Kneller and Hawig (1991), who

investigated the combined effect of two finely dis-

persed and mutually exchange-coupled magnetic

phases. One of these phases has a large uniaxial an-

isotropy constant and is able to generate a high

coercivity. By contrast, the second phase is magnet-

ically soft. It has a larger magnetic ordering temper-

ature and concomitantly a larger average exchange

energy than the hard phase. It is the comparatively

high saturation magnetization of the soft phase that,

when the latter is exchange coupled to the hard phase,

provides a high remanence to the composite magnet.

The possibility to prepare magnets showing reman-

ence enhancement has triggered extensive research in

this area (see Magnets: Remanence-enhanced ).

In most of the systems for which remanence en-

hancement has been reported, the magnetically soft

phase is a-Fe or an iron-rich or cobalt-rich alloy.

Examples of magnetically hard phases are Nd

2

Fe

14

B,

Sm

2

Fe

17

N

3

,Sm

2

Co

17

, and Nd(Fe,Mo)

12

N

x

. The

microstructures of all these composite magnets have

in common that they consist of a very fine distribu-

tion of the magnetic particles, falling into the nano-

meter range. In order to reach this fine distribution

various techniques are employed, including melt

spinning and mechanical alloying (see Magnets: Me-

chanically Alloyed). This group of materials is re-

ferred to as lean rare earth permanent magnets. Their

advantages compared with the standard alloys are

their excellent corrosion resistance and the fact that

they reach saturation in a comparatively low applied

field. A disadvantage is their relatively low coercivity.

The possibility of using these materials in resin-bond-

ed magnets has been described by Croat (1997).

Another interesting group of materials are inter-

stitially modified R

2

Fe

17

compounds. Although the

low Curie temperatures and comparatively low mag-

netocrystalline anisotropies make the R

2

Fe

17

com-

pounds less attractive for applications as permanent

magnet materials, considerable improvements with

respect to Curie temperature anisotropy and co-

ercivity have been reached by forming interstitial

solid solutions obtained by combining these materials

with carbon or nitrogen. The composition of

the corresponding ternary nitrides and carbides

R

2

Fe

17

C

x

and R

2

Fe

17

N

x

is generally believed to be

restricted to the range 0pxp3. More details about

the formation ranges and location of the interstitial

atoms the lattice are described in the review of Fujii

and Sun (1995).

Resin-bonded magnets from nitrogenated Sm

2

Fe

17

powders have been prepared with BH

max

¼

136 kJm

3

, B

r

¼ 9:0T, and m

oB

H

c

¼ 6:5T. In order

to explore the favorably low temperature coefficient

of the coercivity in magnet bodies suitable for high-

temperature applications Rodewald et al. (1993) and

Kuhrt et al. (1993) have investigated tin- and zinc-

bonded magnets. In these cases, however, the ob-

tained remanences were fairly low (B

r

o0.7 T).

3. Applications of Bonded Magnets

Bonded ferrite magnets are commercially available in

isotropopic and anisotropic grades (see Table 1). The

calendered material is commonly called sheet. Sheet

magnets are mainly used by screenprinters for adver-

tising specialties, novelties, and picture frames. Sign

manufacturers use it for vehicle signs, but there are

also medical applications such as needle counters.

Extruded profile flexible magnets are called strip.

They are used for a variety of gasket applications such

as for refrigerator doors, shower doors, and remov-

able storm windows. Other applications are in small

861

Magnets: Bonded Permanent Magnets

motors and stereo speakers. Injection-molded ferrite

magnets are mainly used in automotive applications,

office automation, and in small motors. A great ad-

vantage of the ferrite magnets is that they are inex-

pensive and the raw materials are readily available.

Bonded SmCo-type magnets are used in applica-

tions where the temperature coefficients of remanence

and coercivity have to be low and where a high cor-

rosion resistance is required. Compared to bonded

ferrite and NdFeB magnets their market share is low

because of the high price of the raw materials.

The majority of bonded NdFeB magnets are used

in personal computers but they are also used in a

fairly wide range of automotive, consumer, and office

products including VCRs, camcorders, and printers,

and in smaller appliances such as watches, clocks,

timer switches, and cameras. Most of the bonded

NdFeB magnets go into various types of electric mo-

tors. The most prominent types of electric motors are

spindle motors and stepper motors. Stepper motors

have fairly small sizes and are characterized by their

ability for precise incremental position or speed

adjustment with electric pulses from digital control-

lers. In modern stepper motors, the stators consist of

the coils system and the rotors are made of rare earth

permanent magnets. The advantage of using rare

earth permanent magnets is their high coercivity,

which makes it possible to axially magnetize the rotor

through the thickness with a large number of poles on

the circumference. This allows fairly low step angles.

The number of spindle motors produced is lower than

the number of stepper motors. Spindle motors are

much larger than stepper motors. This is the reason

why they still consume a relatively large percentage of

bonded NdFeB magnets. The largest application of

electric motors is in computer peripherals, where they

serve, for instance, as hard disk drive spindle motors,

CD-ROM pick-up motors, CD-ROM spindle mo-

tors, floppy disk drive spindle motors, and floppy

disk head actuators.

For a more detailed discussion of bonded mag-

net manufacturing, their performance, and their

applications the reader is referred to the review ar-

ticles of Croat (1997), Ormerod and Constantinides

(1997), and Ma et al. (2002).

See also: Magnetic Materials: Domestic Applica-

tions; Textured Magnets: Deformation-induced

Bibliography

Buschow K H J 1997 Magnetism and processing of permanent

magnet materials. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Magnetic

Materials. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, Vol. 10. Chap. 4

Croat J J 1997 Current status and future outlook for bonded

neodymium permanent magnets. J. Appl. Phys. 81, 4804–9

Fujii H, Sun H 1995 Interstitially modified intermetallics of rare

earth and 3d elements. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Handbook of

Magnetic Materials. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, Vol. 9.

Chap. 3

Harris I R 1992 The use of hydrogen in the production of

Nd-Fe-B-type magnets and in the assessment of Nd-Fe-B-

type alloys and permanent magnets—an update. Proc. 12th

Int. Workshop Rare Earth Magnets and their Applications,

Canberra, 1992, pp. 347–71

Kneller E F, Hawig R 1991 The exchange spring magnet: a new

material principle for permanent magnets. IEEE Trans.

Magn. 27, 3588–600

Kobayashi K, Iriyama T, Imaoka N, Suzuki T, Kato H,

Nakagawa Y 1992 Permanent magnet material of Sm

2

Fe

17

N

x

compounds obtained by reaction in NH

3

-H

2

mixture gas at-

mosphere. Proc. 12th Int. Workshop Rare Earth Magnets and

their Applications, Canberra, 1992, 32–43

Kuhrt C, Schnitzke K, Schultz L 1993 Development of

coercivity in Sm

2

Fe

17

(N,C)

x

magnets by mechanical alloy-

ing, solid–gas reaction, and pressure-assisted zinc bonding. J.

Appl. Phys. 73, 6026–8

Ma B M, Herchenroeder J W, Smith B, Suda M, Brown D N,

Chen Z 2002 Recent developments in bonded NdFeB mag-

nets. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 239, 418–23

Ormerod J, Constantinides S 1997 Bonded permanent magnets:

current status and future opportunities. J. Appl. Phys. 81,

4817–20

Rodewald W, Wal B, Katter M, Veliscescu M, Schrey P 1993

Microstructure and magnetic properties of Zn- or Sn-bonded

Sm

2

Fe

17

N

x

magnets. J. Appl. Phys. 73, 5899–901

Table 1

Maximum energy products (kJ m

3

) of commercially available bonded magnets (from Ormerod and Constantinides

1997).

Magnet powder Manufacturing route Magnetic isotropic Magnetic anisotropic

Ferrite Calendered 4.0–5.0 11.2–12.8

Extruded 3.2–4.8 9.6–12.0

Injection molded 4.0–6.4 12.0–13.6

SmCo Injection molded 68–76

Compression 104–136

NdFeB Calendered 39–41

Injection molded 40–42 76–88

Compression 64–88 112–128

862

Magnets: Bon ded Permanent Magnets

Takeshita T, Nakayama R 1992 Magnetic properties and

microstructures of the Nd-Fe-B magnet powders produced

by HDDR process. Proc. 12th Int. Workshop Rare Earth

Magnets and their Applications, Canberra, 1992, pp. 670–81

Tomida T, Choi P, Maehara Y, Uehara M, Tomizawa H,

Hirosawa H 1996 Origin of magnetic anisotropy formation

in the HDDR-process of Nd

2

Fe

14

B based alloys. J. Alloys

Compds. 242, 129–35

K. H. J. Buschow

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam

The Netherlands

Magnets: HDDR Processed

The HDDR (hydrogenation–disproportionation–des-

orption–recombination) process is a method for pro-

ducing magnetically highly coercive rare-earth (RE)

transition-metal (TM) materials by applying a re-

versible chemical reaction with hydrogen gas (Takes-

hita and Nakayama 1989, McGuiness et al. 1990). In

magnets made from rapidly quenched or mechani-

cally alloyed magnets, the high coercivity is achieved

by reducing the average grain size of the anisotropic

ferromagnetic phase (see Magnets: Mechanically

Alloyed). The average grain size for the HDDR ma-

terial is around 0.3 mm which is approximately an

order of magnitude greater than those of rapidly

quenched or mechanically alloyed material. The cru-

cial difference, however, between the HDDR and

melt-spun or mechanically alloyed materials is that in

the former case it is possible to produce anisotropic

powders without applying mechanical deformation.

This article starts with a general description of the

HDDR process including the thermodynamic and

kinetic aspects. Emphasis will be given in the discus-

sion of possible origins for the anisotropic character

of HDDR-treated Nd–Fe–B-based powders, and to

technical and economical aspects of preparing mag-

nets from HDDR powders. Finally, an outlook on

further prospects of HDDR magnets will be given.

1. General Description of the HDDR Process

Hydrogen is already used very successfully for the

hydrogen decrepitation process, which is most effec-

tive in terms of producing powders, e.g., for sintered

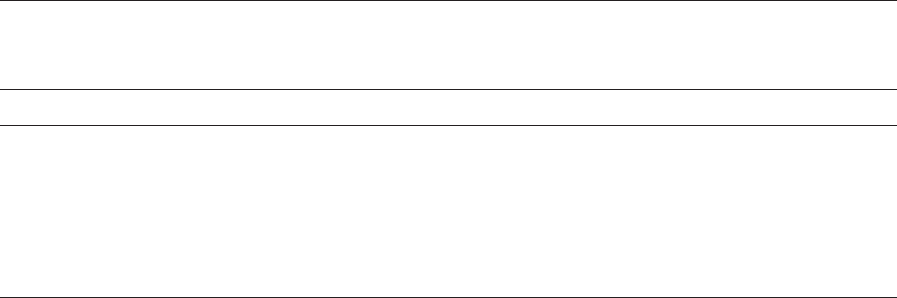

Figure 1

Schematic representation of the HDDR process. Microstructural changes are illustrated by SEM and TEM images of

Nd–Fe–B material (I: starting powder after hydrogen decrepitation; II: disproportionated material (TEM); IV:

particle fracture surface after HDDR).

863

Magnets: HDDR Processed

magnets (see Magnets: Sintered). Another potential

application of hydrogen is in the HDDR process. A

general schematic representation of this process is

given in Fig. 1. In the first step, an AB

n

compound

(where A is a hydride former, e.g., a RE element) is

heated in hydrogen. In many cases, an interstitial

hydrogen absorption takes place at lower tempera-

tures, which results in the hydrogen decrepitation

of the ingot material and this is predominantly an

intergranular fracture process. This decrepitation can

be avoided by heating under vacuum and introducing

the hydrogen at a temperature where the dispropor-

tionation takes place spontaneously. This ‘‘solid’’-

HDDR process is a useful tool for investigations

which demand compact samples such as for TEM

observations and electric resistivity measurements

(Gutfleisch et al. 1994). The simplest representation

of the exothermic disproportionation reaction is

given by:

AB

n

þð17

1

2

xÞH

2

-AH

27x

þ nB þ DH ð1Þ

where DH is the enthalpy, þDH being an exothermic

reaction and DH an endothermic reaction.

The value of x depends on the precise processing

conditions. The second step of the HDDR process is

the recombination reaction under vacuum or low

hydrogen pressure. The hydrogen is desorbed during

stage III and the remaining A-rich regions act as

nuclei for the recombination of the original AB

n

phase:

AH

27x

þ nB-AB

n

þð17

1

2

xÞH

2

DH ð2Þ

By carefully controlling the process parameters of

the recombination reaction, grain sizes of a few hun-

dred nanometers can be obtained. This is of the same

order of magnitude as the single domain particle size

of magnetically highly anisotropic RE–TM com-

pounds such as Nd

2

Fe

14

B and SmCo

5

.

2. Thermodynamics and Kinetics

In principle, the HDDR process is applicable to a

large number of AB

n

-type compounds, e.g., with a

RE element as a very strong hydride former A, and a

TM and/or another element as nonhydride former B.

This is especially true for those compounds with a

high RE content and with a relatively low thermo-

dynamic stability.

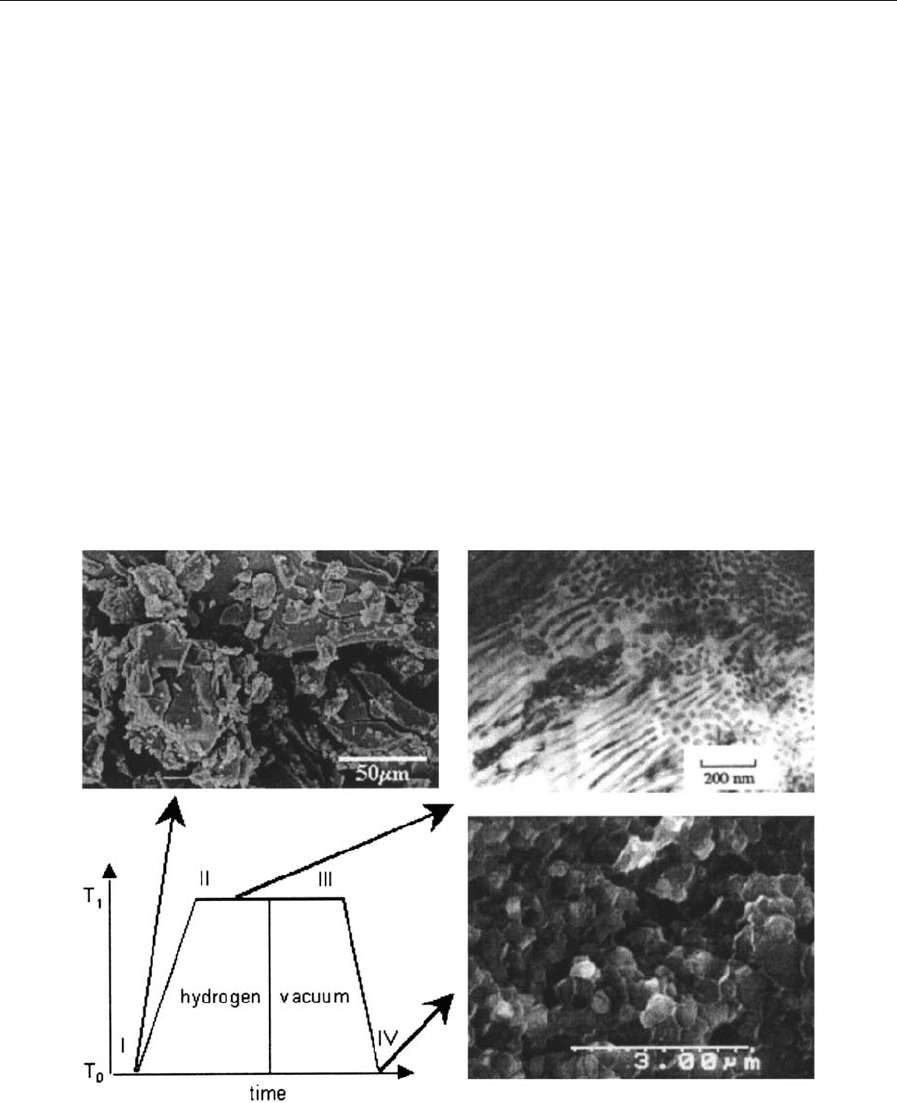

Figure 2 shows a phase diagram of the hydrogen–

AB

n

system. It can be seen that, at a sufficient

hydrogen pressure p (H

2

), the AB

n

phase is in a me-

tastable state at room temperature (T ¼T

0

). The dis-

proportionated state is the thermodynamically stable

state, but the reaction does not take place because of

insufficient diffusion of the large A and B atoms.

Only when the temperature is raised will the kinetic

barrier (dashed line in Fig. 1) be passed and dispro-

portionation into AH

27x

and B take place. The ki-

netic barrier can be lowered by increasing

the surface-to-volume ratio of the AB

n

material

(smaller particles/grains) or by mechanical activation

(e.g., reactive milling in hydrogen). A more stable

AB

n

compound will lead to a narrowed processing

window. A higher hydrogen pressure leads to an

increased stability of the AH

27x

hydride and hence

the disproportionation of more stable compounds

becomes possible (see Fig. 3). The recombination re-

action will be initiated by lowering p(H

2

) which

makes the AB

n

phase the preferred thermodynamic

choice.

For the RE–TM phases with attractive intrinsic

magnetic properties, the phases Nd

2

Fe

14

B and

Sm

2

Fe

17

N

x

have a relatively low thermal stability

and the HDDR process can be applied easily. The

Figure 3

Schematic free enthalpy diagram for the hydrogen–AB

n

system at T ¼T

1

according to Fig. 2. A

disproportionation of the AB

n

compound into AH

27x

and B is only possible for an increased hydrogen

pressure p

2

4p

1

.

Figure 2

Phase diagram of the hydrogen–AB

n

system. The

disproportionation reaction is given by I-II, the

recombination by II-III. No disproportionation will

take place for an insufficient hydrogen pressure p

1

(I

0

-II

0

).

864

Magnets: HDDR Processed

most important example is the HDDR process of

Nd

2

Fe

14

B:

Nd

2

Fe

14

B þð27xÞH

2

-2NdH

27x

þ 12a-Fe þ Fe

2

B þ DH ð1Þ

0

2NdH

27x

þ 12a-Fe þ Fe

2

B -Nd

2

Fe

14

B

þð27xÞH

2

DH ð2Þ

0

Typical conditions for the disproportionation reac-

tion (Eqn. (1)

0

) are TE800 1C and pE100 kPa. The

recombination is normally carried out at comparable

temperatures under continuous pumping.

The HDDR process is also applicable to the rel-

atively low stability RE(Fe, X)

12

and RE

3

(Fe, X)

29

materials (e.g., RE ¼Nd, Sm; X ¼Ti, V). However,

in these cases the formation of other phases during

recombination is a serious problem. It has been

shown that the HDDR process can also be applied to

more stable compounds such as SmCo

5

and Sm

2

Co

17

when high hydrogen pressure or reactive milling is

applied (Kubis et al. 1998).

3. Anisotropic Character of HDDR-treated

Nd–Fe–B-based Powders

An apparently unique feature of Nd

2

Fe

14

B is the

preservation of the anisotropic character of the pow-

der after the HDDR process. A ‘‘memory-cell’’ model

suggests nanoscale 2:14:1 phase regions rich in addi-

tives such as Co, Ga, or Zr which stabilize the phase.

Therefore these regions remain unaffected during the

disproportionation reaction and can act as nucleation

sites for the recombination reaction. This model is

supported by thermodynamic arguments as well as by

extensive microstructural investigations. However,

there is some evidence that this model is not suffi-

cient: (i) it has, so far, not been possible to maintain

the anisotropic character of Sm

2

Fe

17

-type powders

after the HDDR process by using additions that sta-

bilize the 2:17 phase in the same manner as the 2:14:1

phase; and (ii) it is possible to obtain anisotropic

HDDR powders from ternary Nd–Fe–B materials

without the presence of stabilizing additions by ap-

plying ‘‘solid’’ disproportionation and recombination

in a low hydrogen pressure (‘‘slow’’ recombination).

As neodymium hydride and a-iron have a cubic

crystal structure and do not exhibit preferred cry-

stallographic axes, only the grains of the noncubic

iron boride phase remain as possible ‘‘memory cells.’’

The absence of the boride phase in the dispropor-

tionated state of Sm

2

Fe

17

supports this assumption.

A ‘‘one-to-one’’ crystallographic relation between a

metastable tetragonal Fe

3

B phase and the original

2:14:1 matrix phase has been found in an alloy con-

taining cobalt, gallium, and zirconium (Tomida et al.

1999). This Fe

3

B phase can also be found in solid-

disproportionated ternary Nd–Fe–B materials. The

elemental additions appear to stabilize the Fe

3

B

phase and also to depress excessive grain growth

during recombination. Anisotropic powders are

harder to obtain from ternary materials probably

because the Fe

3

B phase is only an intermediate phase

in the disproportionation reaction and the subse-

quent Fe

3

B-Fe

2

B þFe reaction is not slowed down

by the presence of alloying additions. The ‘‘slow’’

recombination at low hydrogen pressures, e.g.,

10 kPa at 900 1C, enables a better control of grain

growth, which is essential for obtaining a high co-

ercivity in ternary Nd–Fe–B materials together with a

high degree of texture.

4. Technical and Economical Aspects

The HDDR process is an environmentally friendly

and simple method of powder preparation. The com-

bination of hydrogen decrepitation and the HDDR

process makes it possible to produce highly coercive

Nd–Fe–B-type powders from the ingot starting ma-

terial in ‘‘one run.’’ Additionally, the amount of free

a-Fe in cast Nd–Fe–B materials, which has a signif-

icant detrimental effect on the magnetic properties, is

reduced by the HDDR treatment.

The most sensitive part of the HDDR process is the

recombination stage. A scaling up to larger batch sizes

leads to the formation of an inhomogeneous micro-

structure after both processing steps, because of large

temperature gradients caused by the strongly exo-

thermic/endothermic character of the disproportion-

ation/recombination reactions. The inhomogeneous

microstructure of disproportionated material does

not appear to have a great effect on the magnetic

properties of isotropic HDDR powders and hence

batch sizes of 15 kg are applicable. On the other hand,

the batch size for the recombination step has to be

limited to about 2 kg in order to avoid large variations

in grain size which lead to poor magnetic properties.

The application of the slow recombination method

could make a significant contribution to solving this

technological problem.

The possibility of producing highly coercive pow-

ders consisting of nanoscaled grains with a preferred

crystallographic orientation is a special feature of the

HDDR process that makes it extremely interesting

for the cost-effective production of anisotropic hard

magnetic powders. However, the degree of texture of

HDDR materials is limited as there is always a cer-

tain loss of anisotropy after the HDDR treatment of

an anisotropic powder. The best properties of HDDR

magnets are remanences of about 1.2 T combined

with coercivities of m

0J

H

C

41 T, leading to (BH)

max

values of about 250 kJm

3

.

There is a large variety of processing routes for

isotropic and anisotropic HDDR magnets (for more

865

Magnets: HDDR Processed

details see Gutfleisch and Harris 1998). For example,

anisotropic Nd–Fe–B magnets can also be produced

by hot pressing and hot deformation of isotropic

nanoscaled materials (see Textured Magnets: Defor-

mation-induced). It is somewhat harder by this

processing route to obtain high coercivities and re-

manences from HDDR materials compared with the

properties obtained from melt-spun and mechanically

alloyed materials and this can be attributed to the

larger average grain size of the HDDR materials.

However, the addition of grain growth inhibiting

elements such as zirconium and the integral optimi-

zation of HDDR, hot pressing, and deformation still

give room for improvements.

5. Future Prospects of the HDDR Process

Applications at moderate temperatures (B120 1C)

depend, amongst other things, on low irreversible

magnetic losses at these temperatures. There is a

question mark over the long-term magnetic stability

of HDDR magnets at these temperatures which is

much inferior compared with those of melt-spun and

sintered magnets. Work is underway to try and im-

prove the performance of the HDDR material.

Of all the known magnetically highly anisotropic

RE–TM compounds, only the RE

2

Fe

14

B-based ma-

terials have been found to exhibit anisotropic features

after the HDDR process. Magnets with RE ¼Pr ex-

hibit promising properties with more relaxed process-

ing conditions compared with those characteristic of

Nd

2

Fe

14

B. HDDR magnets based on Pr

2

Fe

14

Bor

(Nd

1x

Pr

x

)

2

Fe

14

B could be possible alternatives to

neodymium-based anisotropic HDDR magnets.

The application of high hydrogen pressures opens

the way to preparing a wider range of hard magnets

by the HDDR process from highly stable materials

such as Sm–Co based compounds. These studies

might also help to find new insights into the mech-

anisms of the HDDR process.

Another way of extending the applications of the

HDDR process is the combination with other prep-

aration methods such as ball milling. Reactive milling

in hydrogen can lead, after recombination at low

temperature, to powders with grain sizes of only a

few tens of nanameters. Such materials can exhibit

remanence enhancement due to the effect of magnetic

exchange coupling (see Magnets: Mechanically

Alloyed and Textured Magnets: Deformation-

induced).

See also: Magnetic Materials: Hard; Magnets:

Bonded Permanent Magnets

Bibliography

Gutfleisch O, Harris I R 1998 Hydrogen assisted processing of

rare earth permanent magnets. In: Schultz L, Mu

¨

ller K H

(eds.) Proc. 15th Int. Workshop on Rare-earth Magnets and

their Applications. Dresden, Germany, pp. 487–506

Gutfleisch O, Martinez N, Verdier M, Harris I R 1994 Phase

transformations during the disproportionation stage in the

solid HDDR process in a Nd

16

Fe

76

B

8

alloy. J. Alloys

Compds. 215, 227–33

Kubis M, Handstein A, Gutfleisch O, Gebel B, Mu

¨

ller K H,

Schultz L 1998 HDDR in Sm–Co—a new method for mag-

netic hardening of Sm–Co permanent magnets. In: Schultz L,

Mu

¨

ller K H (eds.) Proc. 15th Int. Workshop on Rare-earth

Magnets and their Applications. Dresden, Germany, pp.

527–36

McGuiness P J, Zhang X J, Yin X J, Harris I R 1990 Hydro-

genation, disproportionation and desorption (HDD): an ef-

fective processing route for Nd–Fe–B-type magnets. J. Less

Common Met. 162, 359–65

Takeshita T, Nakayama R 1989 Magnetic properties and

microstructure of the NdFeB magnet powder produced by

hydrogen treatment. In: Shinjo M (ed.) Proc. 10th Int. Work-

shop on Rare-earth Magnets and their Applications. Kyoto,

Japan, pp. 551–7

Tomida T, Sano N, Hanafusa K, Tomizawa H, Hirosawa S

1999 Intermediate hydrogenation phase in the hydrogena-

tion–disproportionation–desorption–recombination process

of Nd

2

Fe

14

B-based anisotropic powders. Acta Mater. 47,

875–85

I. R. Harris and M. Kubis

University of Birmingham, UK

Magnets: High-temperature

High-temperature permanent magnets with an oper-

ating temperature of over 450 1C are required for fu-

ture advanced power systems. Precipitation-hardened

2:17 Sm(Co

bal

Fe

w

Cu

y

Zr

x

)

z

magnets have large an-

isotropy fields and a high Curie temperature which

make them optimal candidates for such high-temper-

ature applications (Ray 1984). The Sm(Co

bal

Fe

w

Cu

y

Zr

x

)

z

magnets are characterized by a complex

microstructure consisting of a cellular structure

superimposed on a lamellar structure, which is

formed after a lengthy aging at 800–850 1C followed

by a slow cooling to 400 1C (Hadjipanayis 1996). The

cellular/lamellar microstructure is formed during

the aging period. Upon slow cooling copper diffu-

sion takes place to the cell boundaries leading to

the right microchemistry for optimum domain wall

pinning.

The magnets represent a complicated system with

four compositional (x, y, w, z) and five heat treating

variables. Comprehensive and systematic studies

were undertaken on bulk and nanocrystalline rare-

earth cobalt-based magnets to understand their

behavior and improve their high-temperature per-

formance. These studies led to the development of

new high-temperature magnets and to the discovery

of some new effects in these magnets (Liu et al. 1999,

866

Magnets: High-temperature

Tang et al. 2000). Also the studies helped to under-

stand further the effects of composition and process-

ing on the magnetic hardening behavior of the

magnets, particularly on the coercivity and its tem-

perature dependence. In the following the recent

studies on Sm–Co-based high-temperature magnets

in both the cast and nanograined powder form are

summarized.

1. Bulk Sm(CoFeCuZr)

z

Magnets

1.1 Effect of Composition and Processing

In principle, high-temperature magnets must have a

high Curie temperature, a high anisotropy field H

A

with a small temperature dependence, and high mag-

netization. In addition the magnets must have the

right microstructure for optimum magnetic harden-

ing. Comprehensive studies by Hadjipanayis and co-

workers (Liu et al. 1999, Tang et al. 2000) on the

microstructure and the magnetic properties of the

precipitation-hardened 2:17 Sm(Co

bal

Fe

w

Cu

y

Zr

x

)

z

high-temperature magnets showed that the magnets

must not only have a small (70–100 nm) and uniform

cellular structure (2:17 cells surrounded by 1:5 cell

boundaries) but also the right microchemistry, with a

large gradient of copper at the cell boundaries. This is

made possible by the presence of a thin lamellar

phase (zirconium-rich Z phase), which facilitates the

diffusion of copper to the 1:5 cell boundary phase

during the slow cooling.

The large difference in copper content across the

cell boundaries leads to a steep gradient in domain

wall energy, which causes domain wall pinning, and

gives rise to high coercivity. The microstructure and

microchemistry strongly depend on the composition

and processing of the magnets. Lower-ratio z mag-

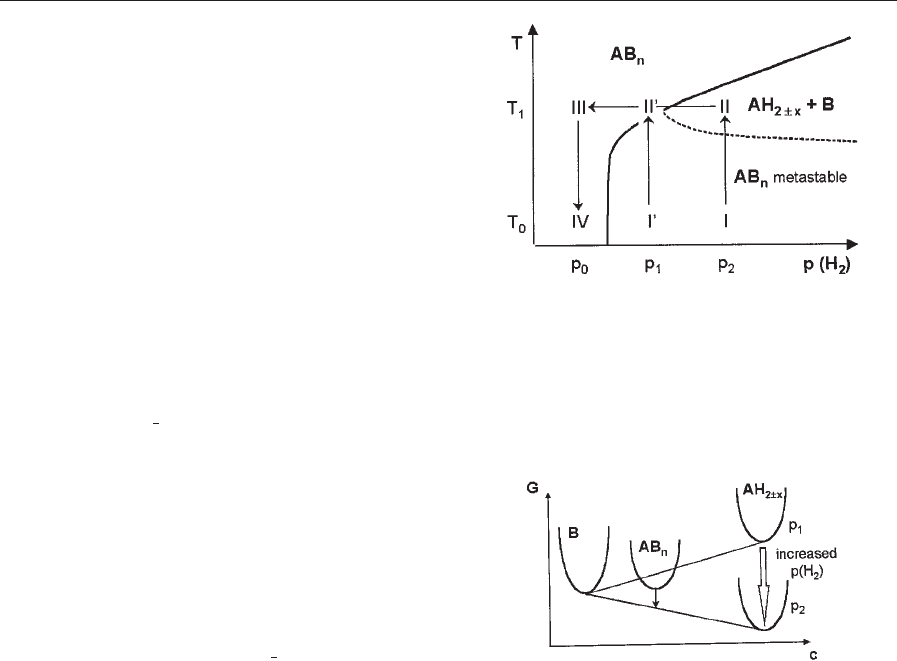

nets have a smaller cell size (Fig. 1) because of the

small percentage of 2:17 phase. A smaller cell size

results in a lower coercivity at room temperature with

improved temperature dependence (Hadjipanayis

1999). Since copper is concentrated at the 1:5 cell

boundaries, an increase in copper content y results in

the formation of a greater amount of 1:5 cell bound-

ary phase (and therefore smaller cells) with higher

copper content and thus higher room-temperature

coercivity. An increase in iron content w results in an

increase of the cell size because iron mainly goes into

the 2:17 cells.

This leads to higher saturation magnetization mag-

nets, but with a greater temperature dependence of

coercivity because of the decrease in both the aniso-

tropy and the Curie temperature of the iron-substi-

tuted 2:17 phase (Strnat 1988). The addition of

zirconium promotes the formation of the lamellar

microstructure, which leads to the optimum uniform

microstructure (Tang et al. 2000), as explained be-

fore. The aging temperature controls the cell size with

a higher aging temperature leading to a larger cell

size. For a fixed copper content any change in the cell

size will alter the copper content in the cell bound-

aries and therefore drastically affect the coercivity of

the magnets and its temperature dependence.

The information derived from the above studies

can be used to fine-tune the microstructure and

microchemistry of the Sm–Co magnets through ad-

justments in the composition and processing para-

meters, and allows the designing of magnets for

high-temperature applications.

1.2 New Magnets with a Record High Coercivity of

10 kOe at 500 1C

By changing the ratio z and using an appropriate

copper content, new magnets with a coercivity of

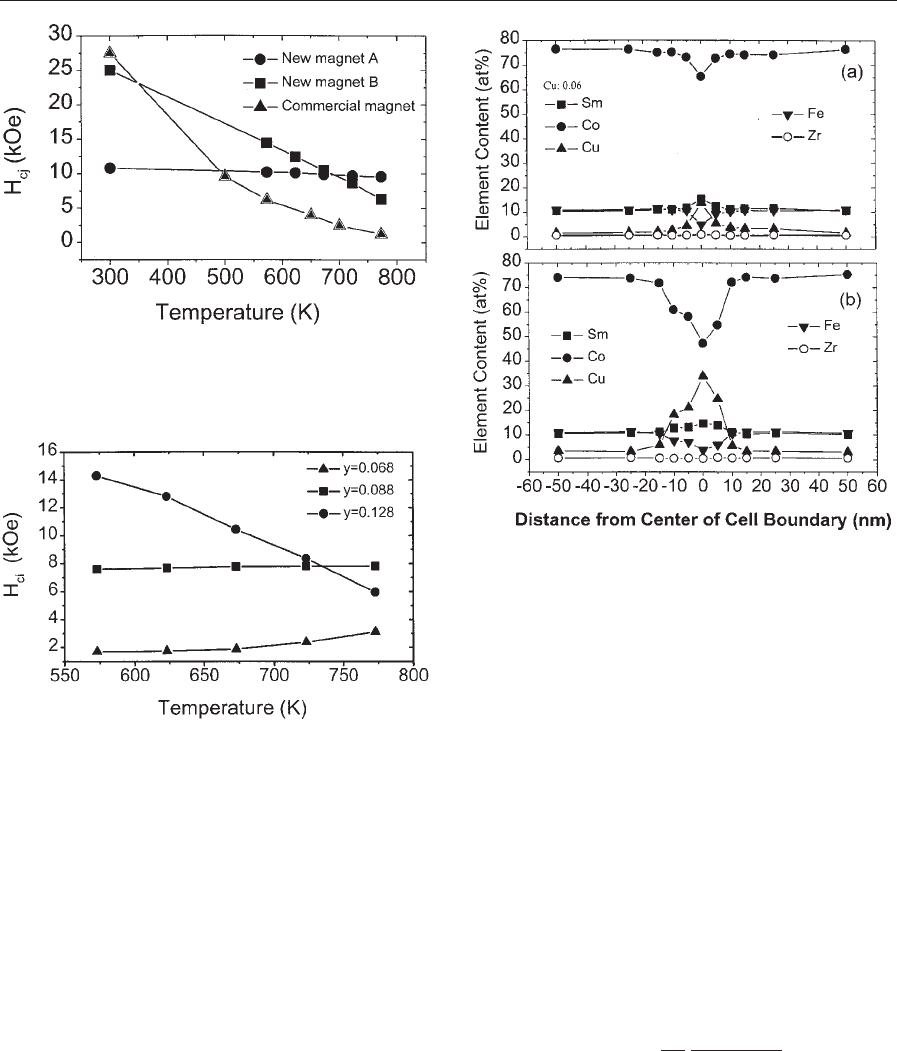

10 kOe at 500 1C were developed. Figure 2 shows the

temperature dependence of coercivity for the new

magnets (A and B) compared with a typical old com-

mercial magnet. For magnet B, with a high ratio z of

8.5 and a copper content of 0.088, the coercivity at

room temperature is about 40 kOe. For magnet A,

with a low ratio z of 7.0 and a copper content of up to

0.128, a record high coercivity of 10.8 kOe at 500 1Cis

Figure 1

Dependence of cell size on ratio z: (a) and (b) z ¼7.0;

(c) and (d) z ¼8.5. The left and right figures are

microstructures perpendicular and parallel to the c axis

of the 2:17 phase, respectively.

867

Magnets: High-temperature

obtained. The temperature coefficient of coercivity for

magnet A is –0.03% 1C

1

, which is more than eight

times smaller than that of magnet B. The new magnets

have a better temperature dependence of coercivity

than the old commercial magnets. The micro-

structural data show that the cell size of magnet B is

larger than that of magnet A (88 nm vs. 108 nm).

These are smaller than the size of commercial magnets

which is generally above 120 nm.

1.3 Temperature Dependence of Coercivity

Controlled by the Copper Content

The effect of composition on the temperature de-

pendence of coercivity was studied systematically.

Figure 3 shows the temperature dependence of co-

ercivity for Sm(Co

bal

Fe

0.1

Cu

y

Zr

0.02

)

7.5

magnets with

different copper content. The temperature coefficient

of coercivity changes from a small positive to a large

negative value with increasing copper content from

y ¼0.068 to 0.128. The microstructure of the copper-

substituted magnets is similar showing a small de-

crease in cell size with increasing copper content

(from 100 to 80 nm). However, a nanoprobe analysis

(Fig. 4) shows that most of the copper goes into the

Sm(Co,Cu)

5

cell boundary phase. When the copper

content in the magnets changes from 0.06 to 0.126,

the copper content at the cell boundaries increases

from 13.7 to 33.8 at.%.

The difference in the copper content at the cell

boundaries leads to a large domain wall energy gra-

dient (associated with the chemical composition gra-

dients) along the cell boundaries and thus to a

different intrinsic coercivity, H

c

,

m

o

H

c

¼ m

o

1

2J

s

ðg

1:5

g

2:17

Þ

d

where g is the domain wall energy, J

s

the spontaneous

magnetization, and d the 1:5 cell boundary thickness

(see Coercivity Mechanisms). Moreover, the domain

wall energy gradient and effective pinning area in

the case of low copper content are much smaller than

Figure 2

Temperature dependence of coercivity in different

magnets.

Figure 3

Temperature dependence of coercivity for

Sm(Co

bal

Fe

0.1

Cu

y

Zr

0.02

)

7.5

with different Cu content.

Figure 4

Nanoprobe analysis of Sm(Co

bal

Fe

0.1

Cu

y

Zr

0.02

)

7.5

magnets: (a) y ¼0.06; (b) y ¼0.12.

868

Magnets: High-temperature

in the high-copper-content magnets. Chui (1999)

explained the latter behavior in terms of repulsive

pinning which leads to the positive temperature co-

efficient of coercivity. This abnormal temperature

dependence of coercivity is of great practical impor-

tance, because the temperature coefficient of co-

ercivity can be manipulated by controlling the copper

content.

2. Nanograined RE–Co Powders Made by

High-energy Mechanical Milling

An alternative way to produce high-performance

RE–Co (RE ¼rare-earth element) high-temperature

magnets is to develop a nanoscale microstructure in

these magnets. The motivation originates from the

well-known size dependence of coercivity which goes

through a maximum value at the single-domain size,

which is a fraction of a micron for most magnets such

as Nd

2

Fe

14

B, Sm

2

Fe

17

(NC)

x

and Sm

2

Co

17

(Manaf

et al. 1993, Hadjipanayis 1999). Therefore, high co-

ercivity is expected to develop in magnets with

a nanoscale grain size. Furthermore, an enhanced

M

r

/M

s

ratio (40.5) is also expected in nanoscale iso-

tropic magnets due to the exchange coupling between

neighboring nanograins (Fischer and Kronmu

¨

ller

1999) (see Magnets: Remanence-enhanced). The

mechanical properties of consolidated nanograin

magnets are expected to be greatly improved. In

general, the nanostructure can be obtained by using

melt-spinning (Coehoorn et al. 1989, Manaf et al.

1993) and mechanical alloying (Schultz et al. 1991,

McCormick et al. 1998) (see Magnets: Mechanically

Alloyed).

2.1 Sm–Co-based Nanograined Magnets

Chen et al. (2000) carried out systematic studies on the

development of nanocrystalline Sm

2

Co

17

-based mag-

nets using mechanical milling. They found that a

nanoscale 2:17 phase with an average grain size of

about 30 nm is developed within the powders which

have an average particle size of about 5 mm. Optimum

magnetic properties of M

s

¼110.5 emu g

1

, M

r

¼66.2

emu g

1

, M

r

/M

s

¼ 0.60, H

c

¼9.6 kOe, and (BH)

max

¼

10.8 MGOe have been obtained in stoichiometric

Sm

2

Co

17

powders. The observed magnetic hardening

is believed to arise from the high anisotropy of the

Sm

2

Co

17

phase and its nanoscale grain size.

A small amount of substitution of zirconium for

cobalt significantly increases the coercivity by in-

creasing the anisotropy field of the Sm

2

Co

17

phase. A

copper substitution in Zr-containing samples further

increases the coercivity by introducing a nanoscale

1:5 phase which forms a uniform mixture with the

2:17 nanograins. This is different from the cellular/

lamellar structure observed in bulk magnets with

the same composition. The highest coercivity of

20.6 kOe has been obtained in the Sm

12

(Co

0.92

Cu

0.06

Zr

0.02

)

88

powders. Substituted iron enters the

cobalt sublattice sites of the 2:17 structure, leading to

an increase of the magnetization but a decrease of the

coercivity. An optimum maximum energy product of

14.0 MGOe is obtained in the Sm

12

(Co

0.7

Fe

0.3

)

88

powders.

2.2 PrCo

5

Nanograined Magnets

On the basis of the above results, the studies were

extended to the PrCo

5

system. PrCo

5

is known to

have a high magnetization and a strong uniaxial

magnetocrystalline anisotropy, and because of this it

has attracted much attention as a promising candi-

date for less-expensive permanent magnets for high-

temperature applications since its discovery in

the 1960s (Strnat 1967). However, the coercivity de-

veloped in PrCo

5

-based sintered magnets is only

4–7.4 kOe (Velu et al. 1989), which is rather low

compared with the anisotropy field of 145–170 kOe

(Strnat 1988) of the PrCo

5

phase. It has been estab-

lished that magnetically hard nanograined PrCo

5

-

based powders can be successfully synthesized by

mechanical milling and subsequent annealing (Chen

et al. 1999).

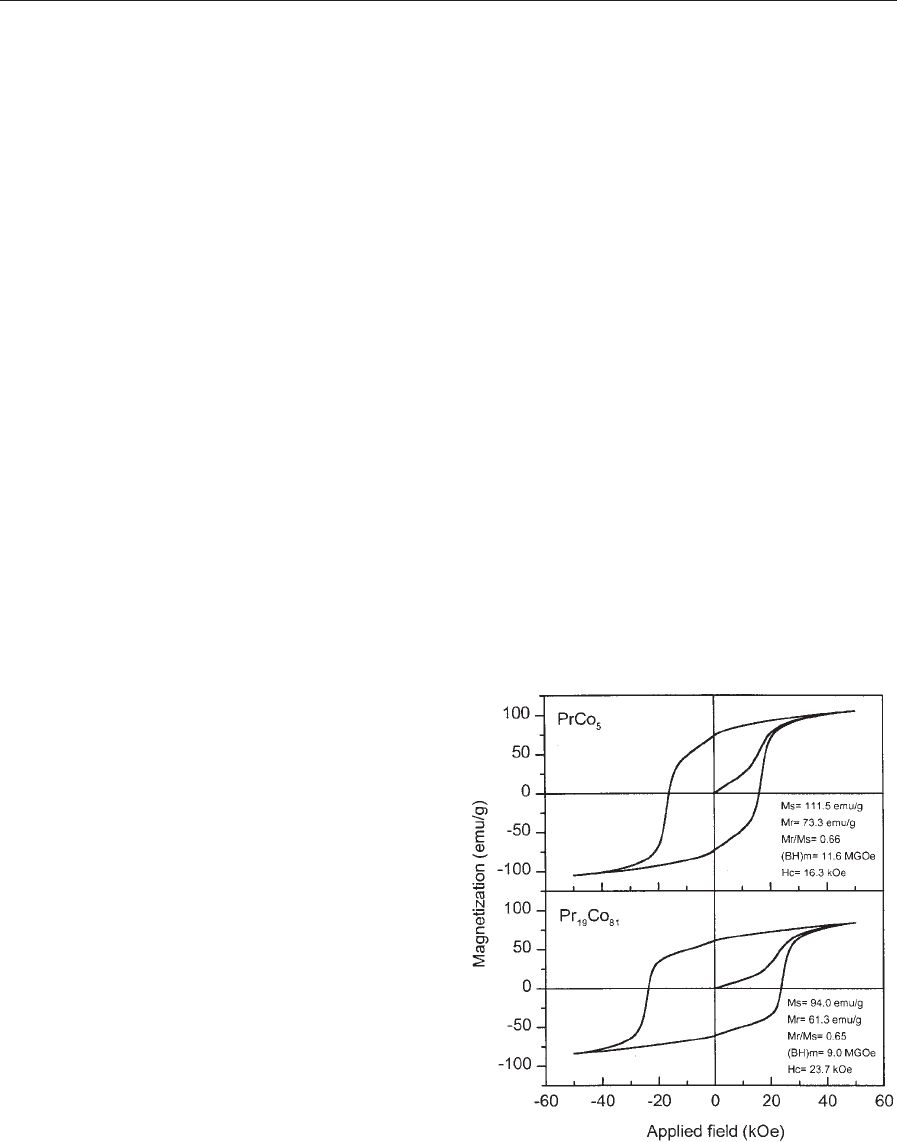

As shown in Figs. 5 and 6, a high coercivity of

16.3 kOe along with a high M

r

/M

s

ratio of 0.66 and

medium-strength maximum energy product of 11.6

MGOe has been obtained in stoichiometric PrCo

5

powders. A coercivity of 23.7 kOe has been obtained

Figure 5

Hysteresis loops of PrCo

5

powders.

869

Magnets: High-temperature