Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

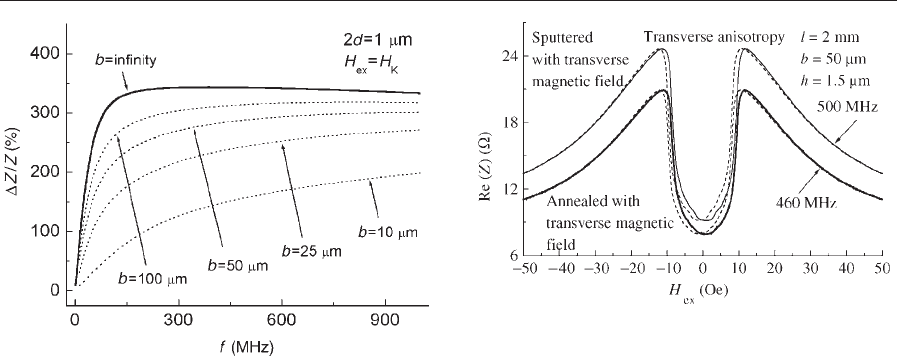

(Makhnovskiy et al. 2000) and the in-plane dimen-

sions (Panina et al. 2001). Figure 1 shows the GMI

ratio versus frequency for a transverse configuration:

the easy axis of the magnetic anisotropy is transverse

with respect to the a.c. current, the d.c. magnetic field

H

ex

is applied in parallel with the current. The GMI

ratio, defined as a maximal impedance change ratio is

expressed as DZ=Z ¼ ZðH

K

ÞZð0Þ

jj

= Zð0 Þ

jj

100%,

where H

K

is the anisotropy field. The function

ZðH

ex

Þ

jj

has a maximum at H

ex

EH

K

, associated

with that for the rotational permeability. Therefore,

the GMI ratio introduced gives the maximum imped-

ance change. The magnetic and electric parameters

taken for the calculations correspond to amorphous

CoFeSiB and Cu sputtered multilayers. For a wide

film (film width b4100 mm, thickness 2d ¼1 mm), the

GMI is B300% in a wide frequency range above

50 MHz, agreeing well with the experimental data.

The GMI ratio is higher for thicker films reaching

600–700% for 2d45 mm and becomes only B20% for

2d ¼0.1 mm. With decreasing b below some critical

value (depending on the transverse permeability and

the thickness of the layers M and F), DZ=Z decreases

substantially. This degradation in the GMI behavior

is related with the flux leakage across the inner lead

(a sort of a.c. demagnetizing). This process is similar

to that resulting in a drop in the efficiency of inductive

recording heads (Paton 1971).

Figure 2 presents the experimental results for im-

pedance versus field behaviour in a sandwich film

with F ¼Ni

80

Fe

20

and M ¼Au. The films are depos-

ited on a glass substrate in the presence of the

d.c. transverse field of B100 Oe. After the deposition,

the films were annealed to release the stress and fi-

nally establish the transverse anisotropy. The field

characteristics have two symmetrical maximums

when the external field equals the anisotropy field

(B10 Oe). The maximal GMI ratio is in the range of

240% for a frequency of 500 MHz. It is smaller than

for the case shown in Fig. 1, since the conductivity

ratio using NiFe films is also smaller. Yet, the sen-

sitivity is very high (24%/Oe) and using NiFe is

practically more preferable.

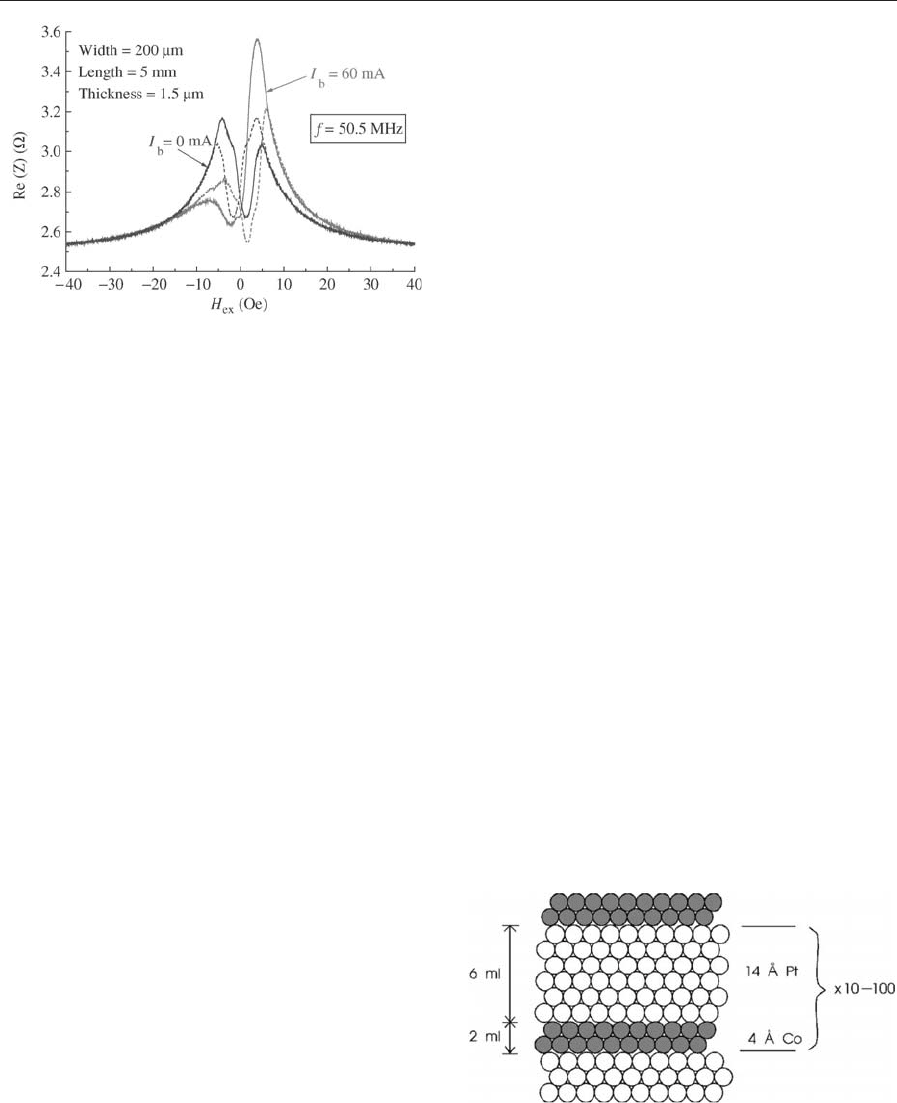

For application in magnetic sensors, not only high

sensitivity but linearity is also important. On the

other hand, the characteristics shown in Fig. 2 are not

only nonlinear but shaped in a way that the operation

near zero field point presents considerable difficulties.

A linear response can be obtained using AGMI char-

acteristics. It was proven that in structures with an

asymmetric arrangement of the static magnetization

(with respect to H

ex

), the impedance also shows an

asymmetric behavior (Panina et al. 1999), for exam-

ple, in multilayers with a cross-anisotropy in the

presence of a d.c. bias current I

b

(Ueno et al. 2000).

Here, we present results for NiFe/Au/NiFe multilay-

ers, in which the upper and bottom magnetic films

were deposited in cross magnetic fields (by rotating

the substrate). Releasing the stress by annealing, a

cross-anisotropy film was finally produced. The

AGMI characteristics obtained in the presence of

the d.c. bias current are given in Fig. 3.

In summary, the GMI effect in multilayers having

in principle two soft ferromagnetic films (F) sand-

wiching a highly conductive lead (M) has significant

advantages over that in a single layer. First, the GMI

ratio is several times higher ranging within 100–600%

for films of 1–10 mm thick. Second, AGMI charac-

teristics needed for linear sensing can be realized us-

ing cross-anisotropy films. The application of GMI

multilayers in establishing new sensitive and quick

response micromagnetic sensors is at an early stage of

its development. However, it can be expected that

Figure 2

Real part of the impedance vs. field in NiFe/Au/NiFe

films with a transverse anisotropy, f ¼450–500 MHz.

Figure 1

GMI ratio vs. frequency in a sandwich with a transverse

anisotropy with the width as a parameter. The total film

thickness 2d ¼1 mm.

780

Magneto-impedance Effects in Metallic Multilayers

significant technical achievements in this field will be

made in the foreseeable future.

See also: Amorphous and Nanocrystalline Materials;

Magnetic Microwires: Manufacture, Properties and

Applications; Magnets Soft; Nanocrystalline Materi-

als: Magnetism

Bibliography

Makhnovskiy D P, Panina L V, Lagar’kov A N, Mohri K 2000

Effect of antisymmetric bias field on magneto-impedance in

multilayers with crossed anisotropy. Sensors and Actuators A

81, 106–10

Mohri K, Panina L V, Uchiyama T, Bushida K, Noda M 1995

Sensitive and quick response micro magnetic sensor utilizing

magneto-impedance in Co-rich amorphous wires. IEEE

Trans. Magn. 31, 1266–75

Morikawa T, Nishibe Y, Yamadera H, Nonomura Y, Takeuchi

M, Taga Y 1997 Giant magneto-impedance effects in layered

thin films. IEEE Trans. Magn. 33, 4367–72

Panina L V, Mohri K, Bushida K, Noda M 1994 Giant mag-

neto-impedance and magneto-inductive effects in amorphous

alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 76, 6198–203

Panina L V, Makhnovskiy D P, Mohri K 1999 Mechanism of

asymmetrical magneto-impedance in amorphous wires. J.

Appl. Phys. 85, 5444–6

Panina L V, Zarechnuk D, Makhnovskiy D P, Mapps D J 2001

2-D analysis of magneto-impedance in magnetic/metallic

multilayers. J. Appl. Phys. 89, 7221–3

Paton A 1971 Analysis of the efficiency of thin-film magnetic

recording heads. J. Appl. Phys. 42, 5868–70

Ueno K, Hiramoto H, Mohri K, Uchiyama T, Panina L V 2000

Sensitive asymmetrical MI efffect in crossed anisotropy sput-

tered films. IEEE Trans. Magn. 36, 3448–50

L. V. Panina and D. P. Makhnovskiy

University of Plymouth, UK

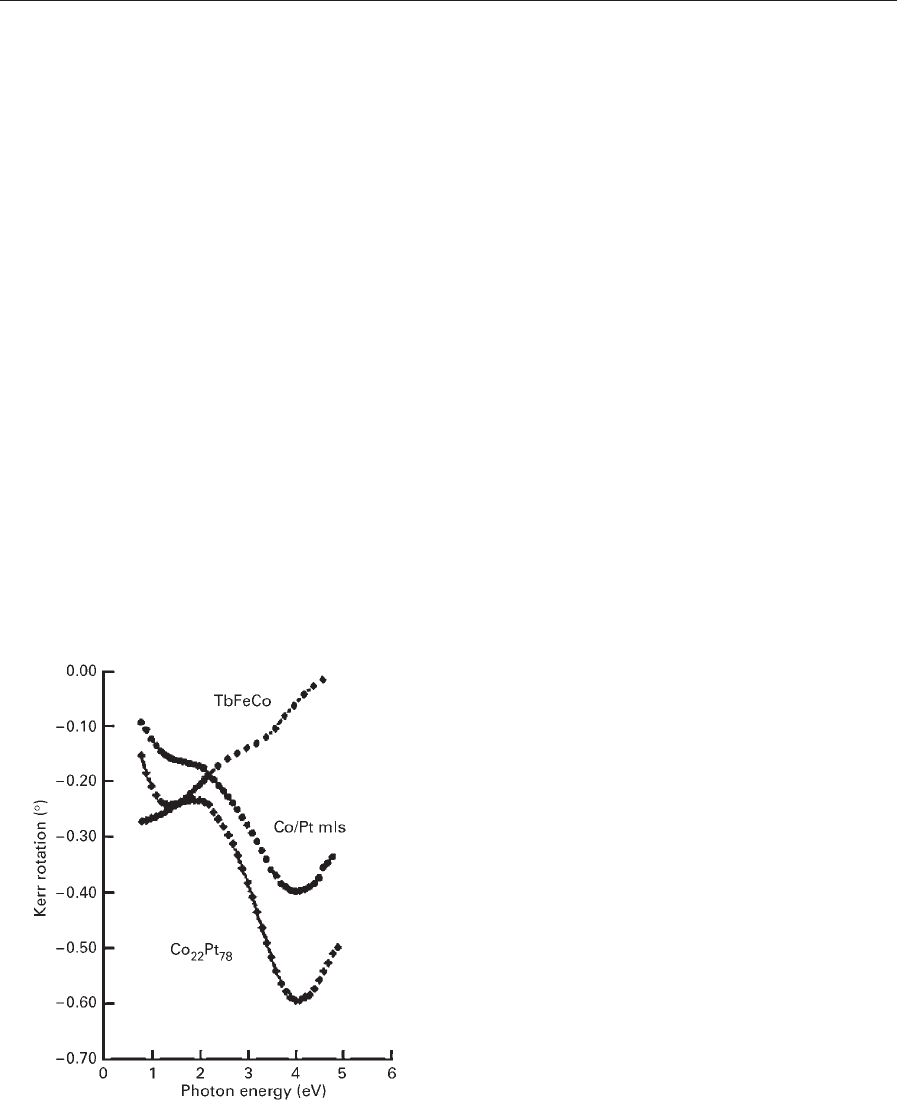

Magneto-optic Multilayers

The performance of magneto-optic (MO) media de-

creases when the wavelength is reduced, and therefore

alternatives with high MO output at short wave-

lengths are needed. Multilayers consisting of very

thin cobalt or CoNi and platinum or palladium layers

have been developed for this kind of application. A

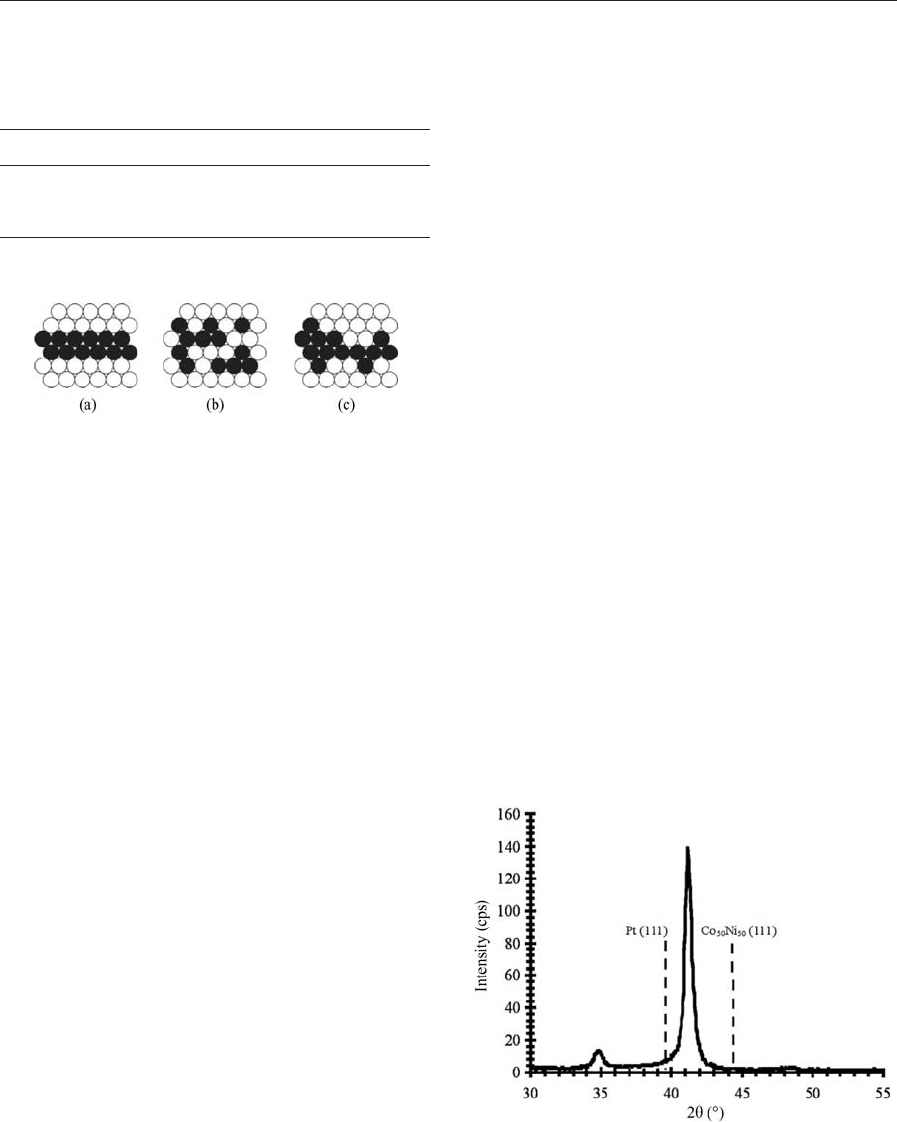

part of a typical multilayer structure is depicted in

Fig 1. The circles represent atoms, and the two

monolayers of cobalt (4 A

˚

) that are drawn are con-

sidered thick layers for application purposes. The

stacking in a real multilayer is not perfect, and differs

from this schematic representation.

Since the early 1980s elements from large sections

of the periodic system have been combined to pro-

duce multilayers, which has resulted in a large

number of publications. A nonmagnetic interlayer

with even better Kerr enhancing properties has been

found: platinum. Co/Pt multilayers have a Kerr ro-

tation of up to 0.51 at about 300 nm (4.2 eV), are

insensitive to corrosion, and owing to the high re-

flectivity they have a higher figure of merit than the

rare-earth (RE) element/transition metal (TM) layers

applied in contemporary MO drives. The rewritabil-

ity is smaller than for RE/TM layers, owing to the

higher Curie temperature of Co/Pt multilayers. This

Curie temperature is between 300 1C and 400 1C for a

good Co/Pt medium. Owing to the high writing tem-

perature that is required, the layers are annealed

during each writing process, which can result in a

decreasing figure of merit when the material is re-

written many times. Magnetic multilayers have been

actively investigated since a perpendicular magnetic

anisotropy was found in Co/Pd and Co/Pt multilay-

ers (Carcia et al. 1985a). MO applications of Co/Pt

and Co/Pd multilayers arose at the end of the 1980s

(Zeper et al. 1989b, Ochiai et al. 1989), with the study

of CoNi/Pt multilayers following (Mes et al. 1993,

Hashimoto et al. 1993, Van Drent 1995).

Figure 3

Real part of the impedance in NiFe/Au/NiFe

multilayers with cross-anisotropy for a d.c. bias current

I

b

¼0 mA and 60 mA.

Figure 1

Schematic of part of a multilayer structure. The bilayer

consisting of a cobalt and a platinum layer is repeated N

times with typically 10pNp100.

781

Magneto-optic Multilayers

The Co/Pd, Co/Pt, and CoNi/Pt multilayers dis-

cussed in this article meet most of the requirements of

the next generation of MO media. MO media use

wavelengths from about 820 nm to 680 nm. At shorter

wavelengths, the detection of smaller bits is possible

as the size of the smallest light spot depends on this

wavelength. Reducing the wavelength by a factor of

two will increase the density by a factor of 4. Reduc-

tion of the wavelength can be achieved with a laser

generating blue–green light or by frequency doubling.

The Curie temperature is an important system pa-

rameter, but the media should also have a large Kerr

rotation, perpendicular anisotropy, square hysteresis

loop for maximum read signal, and a large coercivity

to preserve the written information and allow stable

small domains/bits. By tailoring the deposition pro-

cess, selecting the materials, and designing the layer

structure it is possible to make multilayers that feature

a high MO output at short wavelengths, good mag-

netic properties, and a Curie temperature between

250 1C and 300 1C. A comparison between an RE/TM

MO recording medium and a Co/Pt one is shown in

Fig. 2 by plotting the Kerr rotation. It can be clearly

seen that the rotation at smaller wavelengths is much

better for the multilayer configuration.

The potential application of Co/Pt and Co/Pd

multilayers has motivated numerous studies on their

fundamental magnetic, MO, and practical MO re-

cording properties. Co/Pt multilayers are more at-

tractive for MO recording than Co/Pd multilayers

because the Kerr effect of the former is larger. The

perpendicular magnetic anisotropy (PMA) obtained

in magnetic multilayers is mainly attributed to the

interface anisotropy. A large Kerr rotation of Co/Pt

multilayers at short wavelengths is attributed to po-

larization of platinum (Weller et al. 1993). A large

coercivity, H

c

(e.g., 3 kOe), with a square hysteresis

loop can be obtained in Co/Pt multilayers by many

deposition techniques, e.g., using an etched SiN

x

un-

derlayer (Suzuki et al. 1992). The T

c

for Co/Pt mul-

tilayers is higher than that of RE/TM media, which

leads to a requirement for a higher writing temper-

ature, and results in a smaller number of write/erase

cycles before film degradation occurs (Carcia et al .

1991a, 1991b). Therefore, it is important to reduce

the Curie temperature without significantly reducing

the PMA and Kerr rotation. This can be achieved by

adding nickel into the cobalt layer to produce a

CoNi/Pt multilayer that shows a lower Curie tem-

perature and improved MO recording properties

(Mes et al. 1993, Hashimoto et al. 1993, Hashimoto

1994). Furthermore, a key attribute of MO disks

based on RE/TM alloys is their lower optical noise

because of their amorphous properties. In contrast,

Co/Pt multilayers are crystalline with an average

grain size of about 5–10 nm, which causes disk noise

as much as 5–7 dB higher than that for RE/TM me-

dia (Hashimoto et al. 1993). One of the sources of the

disk noise is attributed to polarization variations ow-

ing to surface roughness and dispersion of the mag-

netization axis (Hashimoto et al. 1993). Therefore, to

reduce disk noise, multilayers must be prepared with

a smooth surface and small grains having high ho-

mogeneity and high degree of the texture along the

growth direction.

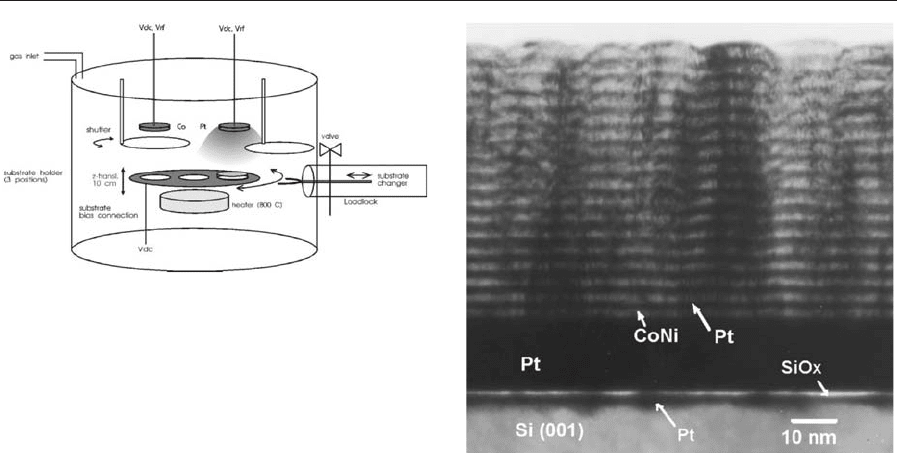

1. Deposition of Multilayers

Multilayer systems as mentioned above can be pre-

pared by vacuum deposition technologies such as

e-beam deposition and sputtering. Because for com-

mercialization a cost-effective manufacturing process

is necessary the sputtering process is the most com-

mon technology.

Figure 3 shows a schematic of a (magnetron) sput-

tering system that has been used for the deposition of

Co(Ni)/Pt(Pd) multilayers. There are more (at least

two) ‘‘sputtering guns’’ mounted in a vacuum cham-

ber. The sputtering guns can be operated using either

radio-frequency (RF) or d.c. power. The target ma-

terial is eroded from the target surface by the incom-

ing positive inert gas ions such as argon, krypton, or

xenon (purity 99.999%). Using a different sputter gas

has an influence on the structure especially the inter-

face structure of the multilayer. Heavier gas (xenon)

reduces the chemical interdiffusion between the mag-

netic and platinum layer but increases the roughness

at the interface compared with using lighter argon gas

Figure 2

Kerr rotation spectra of a 100 nm thick Co

22

Pt

78

alloy, a

77 (3 A

˚

Co/10 A

˚

Pt) multilayer, and a 100 nm thick

Tb

23.5

(Fe

90

Co

10

)

76.5

film (Weller et al. 1992a).

782

Magneto-optic Multilayers

(Carcia et al. 1990, Donnet et al. 1996). In this system,

RF sputtering leads to slow erosion compared with

d.c. sputtering and gives more stable and reproducible

results than d.c. sputtering. Therefore, RF sputtering

has been used for thin magnetic targets (cobalt or

CoNi, 1.5 mm) and d.c. sputtering for thick nonmag-

netic targets (platinum and palladium, 3 mm). In most

cases, a rather low power of 50 W or 100 W is applied

for both RF and d.c. sputtering. For the system in

Fig. 3 the frequency of the RF power supply is

13.56 MHz and the reflected power is tuned to be as

low as possible (o1 W). The deposition pressure dur-

ing sputtering varies from system to system. For the

system in Fig. 3 most of the samples are deposited at

P

Ar

¼1.6 10

2

mbar and 4.0 10

2

mbar. During

sputtering the substrates can be heated to a few hun-

dred degrees. Also a d.c. bias can be applied to the

substrate table to realize a bias sputter deposition that

influences the thin-film growth. Moreover the subst-

rate can be sputtered, etched and cleaned before it is

deposited. A base pressure of 10

9

mbar can be ob-

tained by warming the chamber with the substrate

heater. The substrate can be transferred through a

load-lock without breaking the vacuum of the process

chamber. As a result, the process chamber can be

pumped down to a base pressure better than 5

10

8

mbar. For sputtering as well as for e-beam evap-

oration the deposition rates (measured on the subst-

rate) are 1–6 A

˚

s

1

. Furthermore, the shutter time, the

table rotation, and sputtering pressure are fully con-

trolled by a computer.

2. Thin-film Growth by Sputtering

A transmission electron microscopy (TEM) cross-

section of a typical CoNi/Pt multilayer is shown in

Fig. 4. This multilayer structure is prepared on a sili-

con substrate. The first layer is a relatively thick

platinum seed layer to obtain a good crystallographic

orientation. For this particular purpose the multilayer

is made much thicker to demonstrate the growth more

clearly. At the bottom, the layers are smooth and flat

owing to the smooth and flat surfaces of the substrate

and the platinum seed layer. A native SiO

x

layer

(a bright line) can be seen on the surface of the silicon

substrate. The platinum atoms can also be seen in the

silicon substrate as indicated in the dark area (plati-

num silicide formation). Moreover, it clearly shows

that the whole stack is composed of individual CoNi

(bright) and platinum layers (dark).

In the sputtering process the kinetic energy of the

incident atoms plays an important role in the growth

of the thin-film microstructure. Consideration of the

incident flux energy should include both the sputtered

atoms and the gas neutrals reflected from the target.

The latter arise from ions, which are accelerated

through the plasma sheath and are neutralized on

reflection at the target. On their way from the target

to the substrate both types of atom are thermalized in

the sputtering gas. Their incident energy is therefore

considerably lower than their initial kinetic energy.

The degree of thermalization is strongly dependent

on the deposition pressure, target to substrate dis-

tance, target composition, and sputtering gas. Fol-

lowing the calculations of Somekh (1984), the kinetic

energy of the incident atoms has been estimated for

the case of sputtering of platinum and CoNi. The

results are shown in Table 1. Because there is only a

small difference in the energies of sputtered platinum

with respect to Co/Ni atoms, no discrimination has

Figure 4

Typical structure of Co(Ni)/Pt multilayers. A cross-

sectional TEM image of a Co

0.5

Ni

0.5

/Pt multilayer with

a composition of (Si/24 nm Pt/(3.8 nm CoNi/1.5 nm

Pt) 17).

Figure 3

Schematic of the magnetron sputtering system used for

the deposition of multilayers.

783

Magneto-optic Multilayers

been made between these two. Clearly, the energetic

bombardment of the reflected argon neutrals is dom-

inant when depositing platinum but drastically de-

creases with increasing argon pressure. The energy of

the deposited atoms decreases as well, by as much as

two orders of magnitude over this range of argon

pressure. Owing to the large variation in the energy of

the incident atoms, thin-film growth can be expected

to be strongly dependent on the deposition pressure,

especially in the case of platinum.

In the case of CoNi/Pt multilayers, Bijker et al.

(1996) have reported strong effects of the deposition

pressure on the microstructure of the multilayers. At

high deposition pressure, voids appear in the thin

film. The cause of void formation is the high degree

of scattering of the sputtered atoms combined with

their very low kinetic energy. Obviously, the state of

the interfaces in such multilayers will also depend on

deposition pressure. Under high-energy bombard-

ment at low argon pressure or at low deposition en-

ergies at high argon pressure, alloyed rough interfaces

may be expected (see Fig. 5).

The interface conditions between the ferromagnetic

layer (Co, CoNi) and nonferromagnetic layer (Pt, Pd)

are also strongly dependent on crystallographic struc-

ture. In the case of Co

50

Ni

50

and platinum they are

both f.c.c. metals, but have a lattice mismatch of ap-

proximately 10%. Although epitaxial growth cannot

be expected, a strong correlation between the textures

of the two layers may exist. The interface will then be

incoherent and both layers have different and/or in-

homogeneous (in-plane) lattice spacing. For Co/Pt

multilayers where f.c.c. to h.c.p. phase transitions

may occur in the cobalt layer, several interesting

growth features have been revealed by x-ray diffrac-

tion (XRD) and high-resolution electron microscopy.

Both the interface structure and the crystallographic

phase are also highly dependent on the designed layer

geometry (i.e., number of bilayers, individual layer

thickness, with or without underlayer, etc.). The mul-

tilayer structure always exhibits additional superlat-

tice peaks in the diffraction patterns. The periodicity

is not related to the crystallographic lattice param-

eters but to the artificial modulation of the multilayer

itself. The structures are always analyzed by both

low- and high-angle XRD measurements. The low-

angle patterns refer more to the chemical modulation

of the multilayers owing to their longer length scale.

Carcia (1988) provides information about the inter-

diffusion of Co/Pd and Co/Pt from low-angle XRD

patterns and concludes that Co/Pd sputtered layers

do have a sharper chemical interface than Co/Pt lay-

ers. The multilayers (Co/Pt, Co/Pd, and CoNi/Pt)

grow preferentially with 111 f.c.c. planes normal to

the direction of growth. Figure 6 shows a typical

high-angle XRD pattern of a Co

50

Ni

50

/Pt multilayer

deposited at an argon pressure of 12 mbar. Two peaks

are observed. The largest peak is present between the

Pt(111) and Co

50

Ni

50

(111) lattice positions and indi-

cates a good (111) texture in both the platinum and

Co

50

Ni

50

layer. Since (111) texture is absent in single

Co

50

Ni

50

thin films, it may be concluded that the

platinum promotes (111) texture in the Co

50

Ni

50

layer. The origin of the ‘‘multilayer’’ peak is the arti-

ficial layer modulation and its position corresponds

to the average lattice spacing in the multilayer.

The dependence of the texture on the deposition

conditions can be discussed by analyzing various

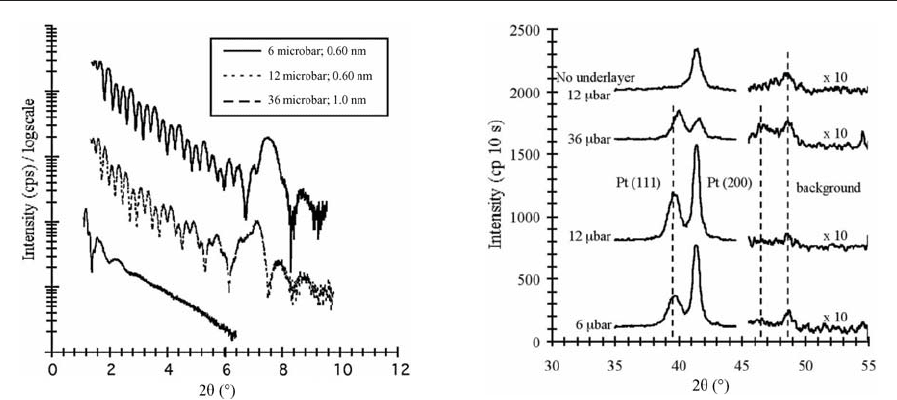

multilayers by XRD. Figure 7 shows the low-angle

Figure 5

Schematic of three different types of interfaces in

multilayers: (a) atomically sharp and smooth;

(b) (non-ordered) alloyed; (c) atomically rough.

Table 1

Estimated energies of argon neutrals reflected from the

targets, E

Ar,Pt

and E

Ar,CoNi

, and of the sputtered atoms

themselves, E

atoms

, bombarding the substrate as a

function of deposition pressure.

p (mbar) E

Ar,Pt

(eV) E

Ar,CoNi

(eV) E

atoms

(eV)

690610

12 50 4 6

36 8 0.5 0.1

Figure 6

High-angle XRD pattern of a Pt (0.8 nm)/(Co

50

Ni

50

(0.7 nm)/Pt (0.8 nm)) 26 multilayer.

784

Magneto-optic Multilayers

XRD patterns of three Co

50

Ni

50

/Pt multilayers

deposited at different argon sputter pressures. For

multilayers deposited at 6 mbar and 12 mbar, the first-

order Bragg peak owing to the layer modulation is

clearly present. The surface roughness obtained from

GIXA simulations (the glancing incidence x-ray anal-

ysis (GIXA) program is commercial software from

Philips Analytical, Almelo, The Netherlands) follows

the trend observed for single platinum thin films.

Figure 8 shows high-angle XRD patterns of four

different multilayers with a CoNi thickness of 0.6 nm

and platinum thickness of 0.7 nm and consisting of 17

multilayers. They are prepared at three different ar-

gon pressures of 6 mbar, 12 mbar, and 36 mbar on a

10 nm seed layer. The upper figure is for a sample

deposited at 12 mbar, prepared without a seed layer,

and consists of nine multilayers.

The diffraction patterns of multilayers deposited

on platinum underlayers at 6 mbar and 12 mbar are

very similar. The platinum underlayers show good

(111) texture and no (200) texture is observed. The

multilayers deposited on top of these underlayers also

show good (111) texture. The underlayer, multilayer,

and satellite peaks have approximately equal inten-

sity. Apparently, microstructural features such as the

local variations in thickness (interface roughness) and

strain of the individual layers are similar in both

conditions. The texture of the platinum underlayer

for multilayers deposited at 36 mbar is poor and sim-

ilar to that of single platinum thin films. The Pt(111)

peak of the underlayer is reduced and also the Pt(200)

peak is observed. Moreover, the intensity of the

multilayer peak is reduced and no satellite peaks are

present. This might point to a simple reduction of

(111) texture of the multilayers, but also to the pres-

ence of larger interface roughness and/or different

intralayer strain may contribute to this effect.

The main peak in the diffraction pattern of the

multilayer without underlayer is considerably smaller

than that of multilayers with underlayer. Probably,

the (111) texture is less owing to the bad initial

growth as reported for single platinum thin films.

This may also explain why the satellite peaks are less

sharp. Then, after several bilayers, the interface

roughness and interlayer strain seems to be not

much different from multilayers deposited with thick

underlayers.

3. Magnetic Properties of Multilayers

The most import magnetic properties are magnetiza-

tion, anisotropy, switching characteristics, coercivity,

and the Curie temperature. These are discussed

below.

3.1 Magnetization

Certain materials that are not ferromagnetic in their

bulk state can become ferromagnetic if placed in

close contact with a magnetic ‘‘host’’ material. This

happens for platinum and palladium combined with

cobalt. Consequently, it has been shown that the

magnetization of Co/Pt and Co/Pd multilayers is

Figure 7

Low-angle XRD patterns of Co

50

Ni

50

/Pt multilayers

deposited at different pressures (6 mbar, 12 mbar, and

36 mbar and various thickness of CoNi layer as indicated

in the legend).

Figure 8

High-angle XRD patterns of Co

50

Ni

50

/Pt multilayers

with t

CoNi

¼6A

˚

. The platinum textures (1110) and (200)

are indicated around 401 and 461 (for more details see

text).

785

Magneto-optic Multilayers

enhanced relative to the value of pure cobalt. This is

not a new phenomenon because the ferromagnetic

polarization of platinum and palladium in diluted

alloys with cobalt and iron is well known. It has been

reported that e-beam deposited Co (0.3 nm)/Pt (1 nm)

layers (Lin et al. 1991) have 30% higher magnetiza-

tion (1850 kAm

1

) than the pure cobalt value

(1422 kAm

1

). Up to 0.6 m

B

induced magnetization

to interface palladium is explained in Broeder et al.

(1987) and 0.9 m

B

in Carcia et al. (1985a). The in-

duced magnetization depends strongly on how per-

fect is the interface from a structural as well as from a

chemical point of view. The polarization in multilay-

ers seems to be lower than in the alloys, which can be

understood by defining the multilayer as a two-di-

mensional structure. Being magnetic, platinum and

palladium also may contribute to the MO activity.

The Kerr effects measured at short wavelengths

(around 300 nm or 4 eV) for Co/Pt multilayers are

much larger than expected, larger even than the Kerr

effects measured for a single infinitely thick cobalt

layer. The enhancement cannot be attributed to mul-

tiple reflections (in the way that dielectric coatings

enhance a MO layer (Gamble et al. 1985)) because

this would result in a noticeable reduction of the re-

flectivity of the multilayer. Typically the reflectivity is

high (R ¼0.4–0.7 (Zeper 1991)). Another explanation

could be that the cobalt layers are so thin that the

effect of the reduced number of neighbors becomes

apparent. The average magnetic moment per cobalt

atom in the bulk is about 1.9 m

B

, but it might be in-

fluenced by the reduced symmetry. Freeman and Wu

(1991) calculated enhancements of magnetic mo-

ments at the metal surfaces of cobalt, nickel, and

iron. The maximum enhancement found for nickel is

23% for a f.c.c. Ni(001) surface, while for cobalt it is

13% for a f.c.c. Co(001) surface. Because very large

enhancements are observed (up to a factor of 5 more

rotation and ellipticity than is expected from the co-

balt alone) the MO activity of platinum should also

be considered.

3.2 Magnetic Anisotropy

The origin of perpendicular coercivity is found in the

magnetic anisotropy. For the magnetic anisotropy

representation a phenomenological formula (Carcia

et al. 1985a, Draaisma et al. 1987) can be written:

K

eff

¼ K

v

þ 2K

s

=t

m

where K

eff

is the measured effective anisotropy (in-

cluding the shape anisotropy,

1

2

m

0

M

2

s

), K

v

and K

s

are

the contributions of the volume and interfacial an-

isotropy of the Ne

´

el type, and t

m

is the individual

layer thickness of the magnetic layers. The result

K

eff

4 0 indicates the easy magnetization axis is per-

pendicular to the film surface, while K

eff

o 0 indicates

the easy magnetization axis is in the film plane.

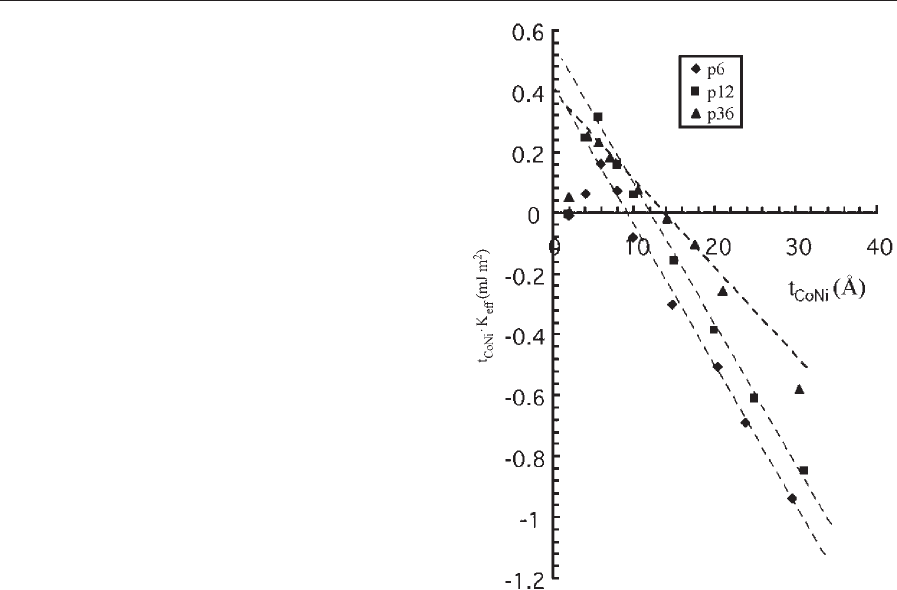

Figure 9 shows the effective anisotropy of three types

of CoNi/Pt multilayers deposited at various argon

sputter pressures. They all have a platinum thickness

of about 0.7 nm, a platinum seed layer thickness of

10 nm, and consist of 17 bilayers.

Compared to multilayers deposited at intermediate

pressure, the interface anisotropy decreases for lower

deposition pressures. This may be explained by con-

sidering the more energetic bombardment of the

multilayer during growth at lower pressure (Carcia

et al. 1990). This is in agreement with the XRD ana-

lysis where no differences between the crystallo-

graphic structure of both series is revealed. For mul-

tilayers deposited at 36 mbar the interface anisotropy

seems to increase with t

CoNi

. A likely explanation is

the presence of significant interface roughness owing

to the low deposition energies of the sputtered atoms

(see Table 1). The consequence is that the effective

interface area increases with t

CoNi

and that the meas-

ured interface anisotropy should be corrected for

this area. Unfortunately, this is not possible. Assum-

ing that for t

CoNi

¼30 A

˚

the measured interface

Figure 9

Effective magnetic anisotropy (expressed as) t

CoNi

K

eff

vs. t

CoNi

for multilayers sputtered with an argon

pressure of 6 mbar, 12 mbar, and 36 mbar.

786

Magneto-optic Multilayers

anisotropy is ‘‘saturated,’’ it may be concluded that

for pressures larger than 12 mbar the true interface

anisotropy still increases with pressure. Apparently,

this effect dominates the expected reduction of inter-

face anisotropy owing to the presence of (200) grains.

Note that the interface roughness is (at least) around

the thickness of the platinum layer, i.e., 8 A

˚

. There-

fore, the interface anisotropy should also be corrected

for the effective platinum coverage, which would give

an even larger value. The interface roughness may

also explain the apparent decrease of magneto-elastic

anisotropy for larger t

CoNi

. Owing to the large inter-

face roughness and thin platinum layer, the growth of

the Co

50

Ni

50

layer may be inhomogeneous. There-

fore, also strain effects may be inhomogeneous in the

Co

50

Ni

50

layer. Quantification of these effects is very

difficult. The interface structure as a function of

deposition pressure has been further characterized

(Kirilyuk et al. 1998) with magnetization-induced

second harmonic generation (MSHG). In general the

magnitudes of K

v

and K

s

depend on the degree of

(111) f.c.c. texture of the multilayer. This texture is

promoted by using platinum seed layers between the

multilayer and the substrate. The explanation of the

origin of the perpendicular anisotropy in this type of

multilayer is still a matter of debate, although in-

depth discussions have been published (Chappert and

Bruno 1988, Draaisma et al. 1987).

3.3 Coercivity, Nucleation, and Saturation Field

In the case of our multilayers, where the magnetiza-

tion is reversed by domain wall motion, the origin of

coercivity is presumably the imperfection of the lay-

ers (Honda et al. 1991, Suzuki et al. 1992). Magnet-

ically inhomogeneous regions act as pinning centers

for the domain walls and thereby hamper their move-

ment through the layer. Suzuki et al. (1992) estimated

the size of these pinning sites for Co/Pt multilayers

with high coercivity and squareness by measurement

of H

c

, K

u

, and M

s

as function of temperature (T ¼

5–400 K). Using the temperature-dependent data in a

simple model, Kronmu

¨

ller et al. (1986) found a pin-

ning site diameter of 4 A

˚

for a sample with well-

defined [111] orientation and good interfacial sharp-

ness (determined by low- and high-angle XRD) while

this diameter increased to 16 A

˚

and 31 A

˚

for less per-

fect structures. As the magnetic polarization of plat-

inum decays quickly with the distance from the

interface, the pinning sites must be located in and

nearby the cobalt layers. Therefore, the values of 4 A

˚

and 16 A

˚

are not surprising. The 31 A

˚

diameter pin-

ning site estimate might be due to inhomogeneity in

the film plane, in addition to the variation along the

film normal (Suzuki et al. (1992). When the nuclea-

tion field, H

N

, is large it can hide both coercivity, H

C

,

and saturation field, H

S

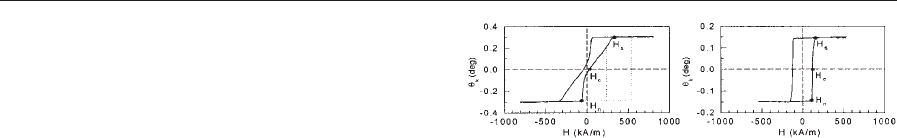

(Zeper et al. 1991). On the

left-hand side of Fig. 10 the nucleation can be clearly

seen as large shoulders occur. At the shoulders the

nucleation energy delays the creation of reversed do-

mains. At field H

N

a steep transition occurs as here

the field is high (low) enough to create the first do-

mains, which immediately stripe out to achieve the

energy balance between applied field, part of the layer

that is reversed, and the corresponding demagnetiz-

ing field. The dotted lines illustrate that first H

C

and

then H

S

will be increased when the nucleation field

becomes larger. When the perpendicular anisotropy

is high, and the layer is very thin, the hysteresis loop

is almost rectangular, as shown on the right-hand

side of Fig. 10. Here the coercivity is about the same

as the nucleation field. A small tail is found just be-

fore H

S

and therefore it is assumed that H

S

is not

‘‘hidden’’ in this case.

For MO recording, where most of the disk is mag-

netized in one direction, H

N

(not H

C

) has to be larger

than the writing field. The rectangular ratio r ¼H

N

/

H

C

should be as close to unity as possible, while H

C

should be large. The small pinning sites that are re-

sponsible for the coercivity are generated during the

sputtering process. Extensive literature about practi-

cal rules of thumb to control coercivity is available

for Co/Pt multilayers. Initial experiments produced

layers with too low a coercivity (300–500 Oe or

25–40 kA m

1

), but several ways have been found to

enhance coercivity such as by tailoring the argon

pressure during deposition, growing the right seed

layer, optimizing the multilayer thickness, etc. As

mentioned above, the multilayers should have a per-

pendicular anisotropy, which means an easy axis of

magnetization perpendicular to the film surface. The

perpendicular anisotropy only occurs if the cobalt or

CoNi layers are very thin (Carcia 1988, Carcia et al.

1985a, Draaisma et al. 1987, Meng 1996, Van Drent

1995).

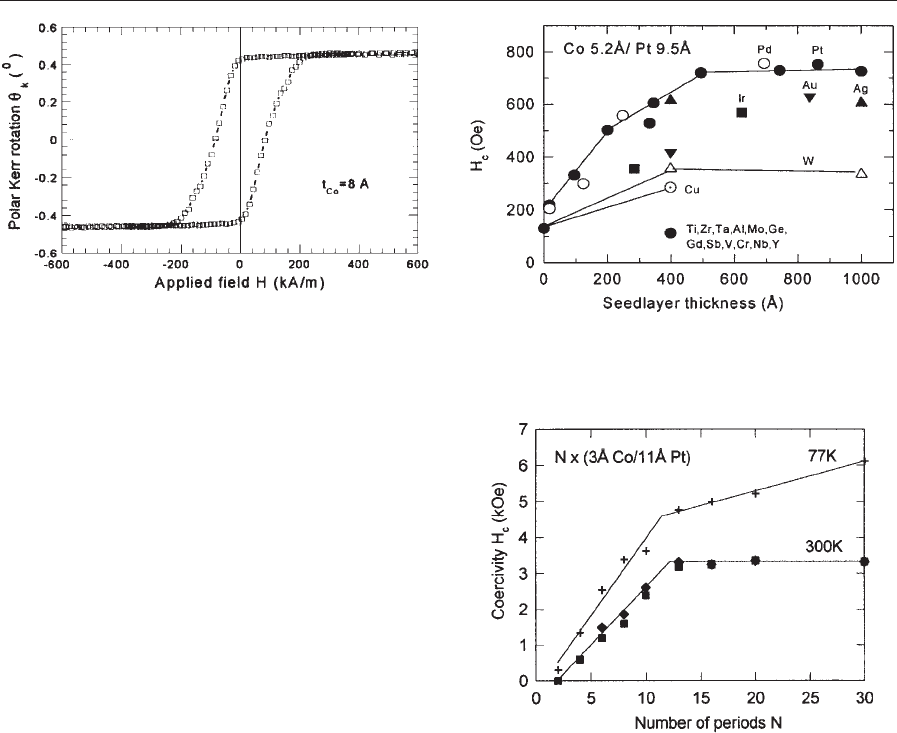

Figure 11 shows the Kerr rotation hysteresis loops

of one series of Co/Pt multilayers with varying cobalt

layer thickness, t

Co

, from 2 A

˚

to 12 A

˚

. The platinum

layer thickness and number of bilayers are kept con-

stant, i.e., t

Pt

¼7A

˚

and N ¼9. As shown in the loops,

the magnetic properties of Co/Pt multilayers are very

Figure 10

Kerr hysteresis loops of two multilayer samples. Left:

sputtered Co/Pt multilayer with clear nucleation field,

H

N

, coercivity, H

C

, and saturation field, H

S

. The dotted

lines illustrate how H

C

and H

S

can be hidden when the

nucleation field is higher. Right: sputtered Co

50

Ni

50

/Pt

multilayer with unity squareness, where H

C

is hidden.

787

Magneto-optic Multilayers

sensitive to t

Co

, which relies on the sensitivity of the

PMA on t

Co

. For thin cobalt layers the loops are

square and the remanent magnetization is equal to

the saturation magnetization. The perpendicular co-

ercivity becomes smaller. Similar observations have

been made for CoNi/Pt layers (Meng et al. 1996c).

(a) Effects of the platinum seed layer on the

coercivity

The platinum seed layer contributes to the important

effects that increase the perpendicular magnetic

anisotropy and the perpendicular coercivity of the

multilayers because of the improvement of the f.c.c.

/111S texture (see Fig. 12) (Meng et al. 1996b).

Furthermore, a platinum seed layer (thicker than

the Kerr information depth) is required for the meas-

urement of the Kerr spectra in order to avoid any

influence from the substrates. However, with disks for

MO applications, the platinum seed layer must be as

thin as possible in order to allow the light to be trans-

mitted through the seed layer without a significant

decrease in the light power on the multilayers. Much

research has been devoted to the selection of the best

seed layer material (Hashimoto and Ochiai 1990), and

the seed layer thickness dependence of virtually every

multilayer parameter (Zeper 1991). Deposition of the

seed layer at elevated temperatures (Shiomi et al.

1993b), applying a bias voltage to the substrate table

(Honda et al. 1991], the influence of soft etch steps on

both substrates (Chang and Kryder 1994) and seed

layers (Suzuki et al. 1992), and the application of

transparent ZnO or SiN

x

seed layers (Carcia et al.

1993, Suzuki et al. 1992) have been reported. Trans-

parent seed layers such as ZnO (refractive index nB2)

enable MO recording from the substrate side, and,

when the seed layer thickness is properly chosen, they

can act as enhancement layers.

(b) Multilayer thickness and coercivity

When the number of bilayers is increased the co-

ercivity will generally also increase. A good example

is given by Weller et al. (1992b) where they present

the coercivity as a function of the number of bilayers,

N (Fig. 13) for N (3 A

˚

Co/11 A

˚

Pt) multilayers

sputtered with argon at a pressure of 20 mbar on a

80 nm underlayer of SiN

x

sputtered at 4 mbar.

Obviously the coercivity increases fast with in-

creasing N when No13, while it stays constant

(300 K) or increases more slowly (77 K) for N413.

An attempt has been made to relate the sharp kink in

coercivities around N ¼13 to the average grain size

Figure 11

Polar Kerr loops of Co/Pt multilayers with varying

cobalt layer thicknesses (series C). The compositions of

films are (Si/16 nm Pt/(t

Co

/7 A

˚

Pt) 9). The

measurements are carried out at room temperature and

l ¼300 nm.

Figure 12

Dependence of coercivity on seed layer material and

seed layer thickness (after Hashimoto and Ochiai 1990).

Figure 13

Thickness-dependent coercivity at 77 K and 300 K.

Series of sputtered N (3 A

˚

Co/11 A

˚

Pt) multilayers as a

function of the number of bilayers N (2 [N] 30) measured

in the perpendicular direction with polar Kerr and/or

AGFM (300 K data) and VSM (77 K data) loops (Weller

et al. 1992a).

788

Magneto-optic Multilayers

(determined from the width of the f.c.c. (111) central

Bragg peak in y–2y XRD) and to the degree of ori-

entation (measured by the width, Dy, of the rocking

curve of the same f.c.c. (111) peak). The average grain

size increases smoothly from D ¼7nm at N ¼6to

D ¼15 nm at N ¼30 and therefore there is no rela-

tionship with the grain size. Dy does decrease with

increasing N, and shows a weak kink between N ¼8

and N ¼10. Here too the correlation with H

C

is not

very convincing. In a study of Zeper et al. (1991) the

slope of the coercivity vs. N also flattened above

N ¼10, but a sharp kink was not found. Also, Meng

(1996) found for CoNi/Pt multilayers an increasing

H

C

until N ¼16.

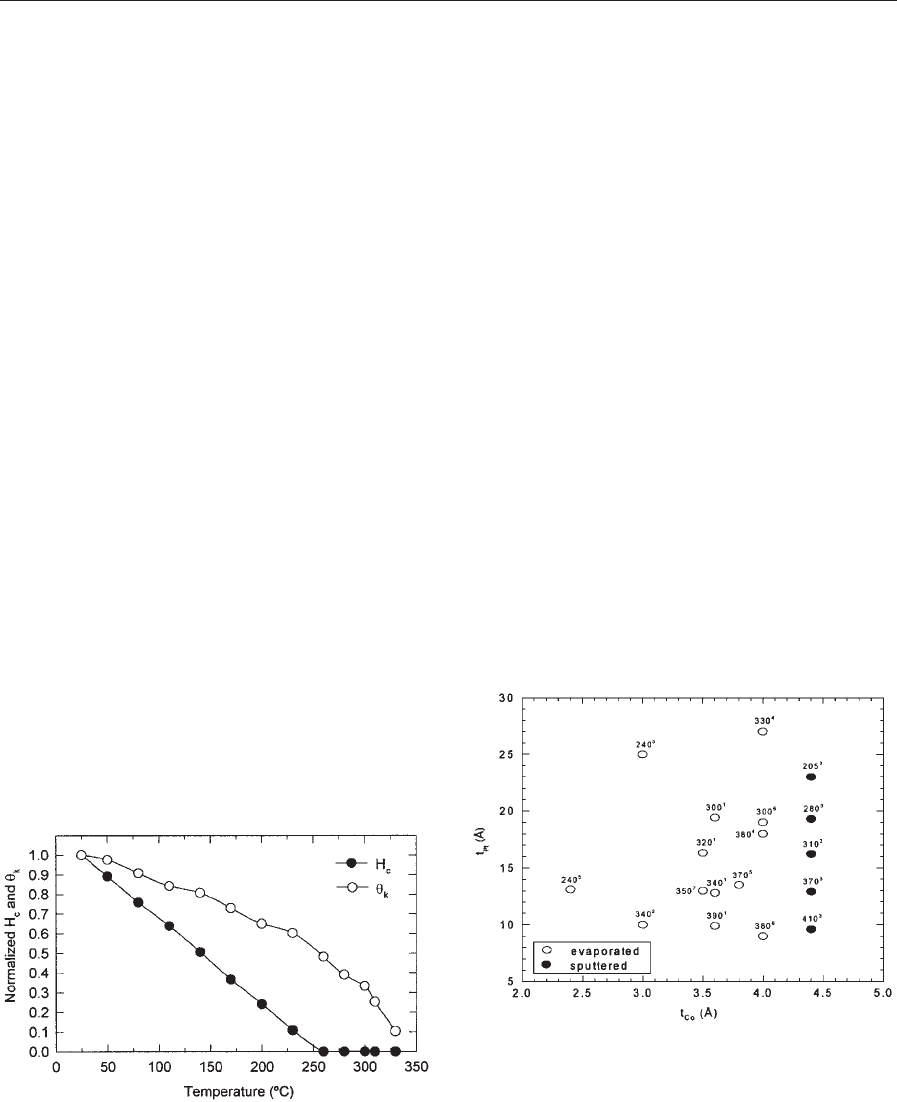

3.4 Curie Temperature

In the thermo-optic writing process a small spot of

the medium is heated (by irradiation of laser light) to

such a temperature that the coercivity is low enough

that the magnetization can be switched by a small

magnetic field. In ferromagnetic materials this tem-

perature is close to the Curie temperature (T

c

) and

therefore T

c

is taken as a design parameter, although

it might be useful to define a temperature where co-

ercivity becomes zero. A striking example is given by

Lin and Do (1990) for a 23 (3 A

˚

Co/10 A

˚

Pt) mul-

tilayer (see Fig. 14), where T

c

is about 330 1C while

the coercivity becomes zero at about 260 1C, a dif-

ference of 70 1C!

Zeper et al. (1989a) reported differences of 15–

30 1C for Co/Pt multilayers with comparable thick-

ness, while this difference increased to 70 1C for a

21 (3.6 A

˚

Co/16.3 A

˚

Pt) multilayer. Carcia et al.

(1991b) found a decrease of 30 1C for a (4 A

˚

Co/9 A

˚

Pt) multilayer and 50 1C for (4 A

˚

Co/19 A

˚

Pt). Ap-

parently this difference increases with increasing in-

terlayer thickness, so it might be attributed to a

decreasing ferromagnetic coupling between the layers.

The Curie temperature should preferably be about

450–500 K (180–230 1C). At the lower end it is limited

by the environment temperature range to which the

medium is subjected and at the upper end by inter-

diffusion, and thus medium degradation (measured

by write–erase cyclability experiments) becomes im-

portant. A lower T

c

also decreases power require-

ments for the diode laser in the recorder. Bulk cobalt

has a T

c

of 1388 K, which is much too high for any

type of thermomagnetic recording. The Curie tem-

peratures that are reported for Co/Pt multilayers de-

pend strongly on the layer thickness involved. The

dependence on the number of bilayers, N (by cou-

pling through the interlayers), becomes small above

N ¼8, according to a model calculation for Co/Pt

multilayers (Bruno 1991). Figure 15 shows various

Curie temperatures reported in the literature for

Co/Pt multilayers. Here sputtered and evaporated

layers with high and low N (where N48) are all

shown on the same graph.

The agreement between the different data sets is

generally good and apparently the different prepara-

tion methods do not influence T

c

strongly. The Curie

temperatures reported by Bloemen et al.(1991)are

extrapolated from temperature-dependent measure-

ments. These extrapolated values are much higher

than the values reported by other authors. The re-

ported T

c

increases with increasing cobalt thickness.

Very thin cobalt layers may not be continuous, there-

by lowering M

s

and thus T

c

. These layers also suffer

Figure 15

Curie temperatures (1C) reported in the literature for

Co/Pt multilayers with varying cobalt and platinum

thickness. The small figures above the temperatures

denote the following references: 1, Zeper et al. (1989b);

2, Lin and Do (1990); 3, Hashimoto (1994); 4, Bloemen

et al. (1991); 5, van Kesteren and Zeper (1993); 6, Carcia

et al. 1991a); 7, Mes et al . (1993).

Figure 14

Temperature dependence of normalized coercivity and

saturated Kerr rotation for a 23 (3 A

˚

Co/10 A

˚

Pt)

multilayer (after Lin and Do 1990).

789

Magneto-optic Multilayers