Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Moments: Magnetism). On application of a magnetic

field, many R-based compounds exhibit transitions in

the magnetization, usually denoted as metamagnetic

transitions, examples of which are presented below.

For a more detailed survey see Gignoux and Schmitt

(1991).

Antiferromagnetic materials with small magnetic

anisotropy may, at a certain field value which usually

is not very high, exhibit a so-called spin-flop transi-

tion in which the collinear antiparallel magnetic mo-

ments rotate to a direction perpendicular to the

applied field, thereby approximately preserving the

collinear structure. This type of metamagnetic tran-

sition is often encountered in gadolinium com-

pounds, which generally have small magnetic

anisotropy since gadolinium has no orbital moment.

Another type of metamagnetic transition, the spin-

flip transition, is found in antiferromagnetic materials

with stronger magnetic anisotropy. In this transition,

a simple single-step phase transition takes place from

the antiferromagnetic state to the forced-ferromag-

netic (magnetically saturated) state. A beautiful ex-

ample is the orthorhombic compound TbCu

2

in

which the terbium moments form a collinear antif-

erromagnetic structure with the moments aligned

along the a direction. If the field is applied along this

direction, a spin-flip occurs in 2 T (Fig. 2). If the field

is applied along the b direction, a similar transition is

observed at almost 40 T after the antiparallel terbium

moments have been rotated from the a to the b di-

rection. In many cases, the magnetization process of

antiferromagnetic compounds is more complex and

two- (Fig. 3) or multistep metamagnetic processes are

involved in reaching the forced-ferromagnetic state.

The occurrence of metamagnetic transitions is not

limited to magnetically ordered R-based materials. In

Fig. 4, the magnetization of the paramagnetic metal

praseodymium is seen to exhibit a metamagnetic

transition. This transition can be ascribed to the

crossing of two crystal field levels, a singlet which is

the ground state in zero field and a magnetic excited

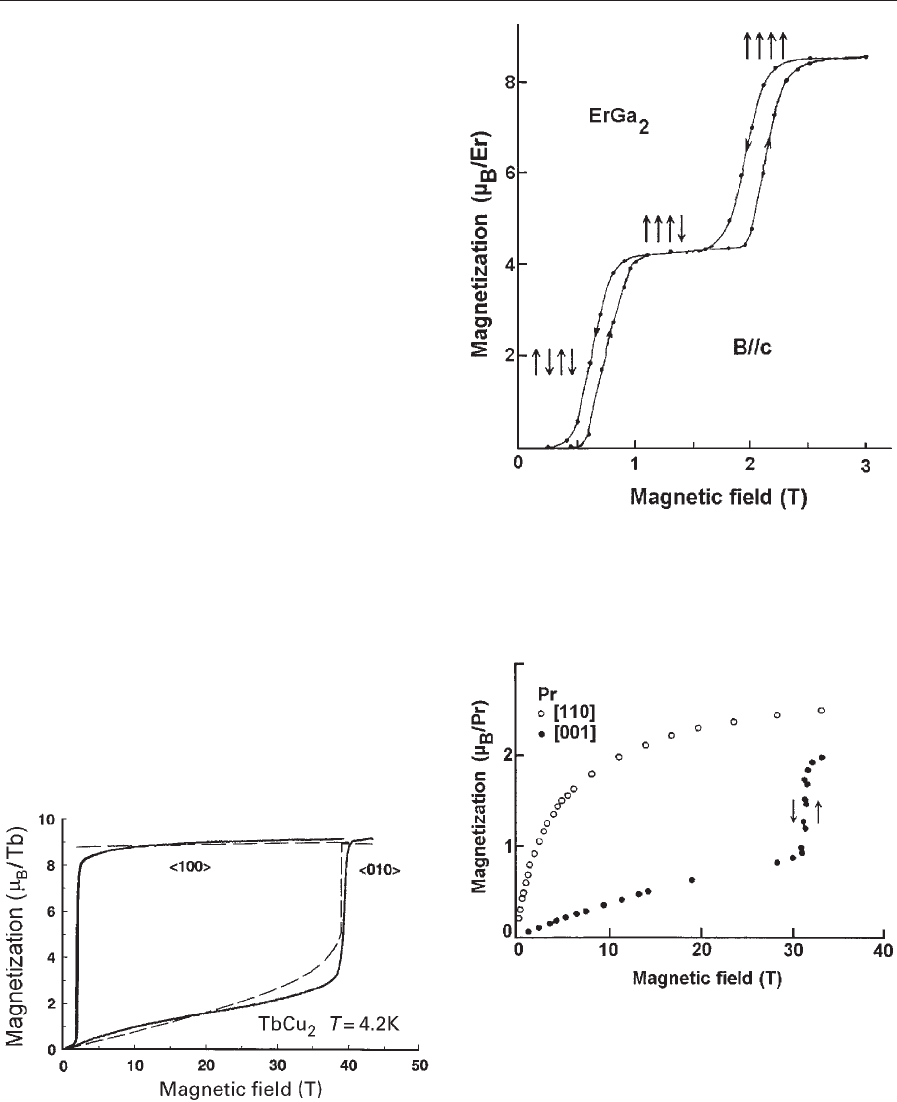

Figure 2

Magnetization of TbCu

2

at 4.2 K in magnetic fields

applied along the a and b axes (after Andreev et al.

1998).

Figure 3

Magnetization of the hexagonal compound ErGa

2

at

different temperatures in a magnetic field applied along

the c axis (after Gignoux and Schmitt 1991).

Figure 4

Magnetization of praseodymium at 4.2 K in magnetic

fields applied along and perpendicular to the c axis

(after Gignoux and Schmitt 1991).

750

Magnetism: High-field

level which has the lowest energy above a certain

value of the applied field.

4. 3d–4f Magnetism

Intermetallic compounds of R metals and the late-3d

transition (T) metals form a very important class of

materials that find numerous applications in e.g.,

permanent magnets, magnetostrictive devices, mag-

neto-optical recording, etc. In the R–T compounds

with T ¼Fe, Co, the strongest interaction is the

3d–3d interaction which primarily determines the

Curie temperature. The 4f–4f interaction is very weak

and can be neglected. The 4f–3d interaction, although

much weaker than the 3d–3d interaction, is of special

importance since by this interaction the strongly an-

isotropic R sublattice magnetization is coupled to the

much less anisotropic T sublattice magnetization.

The interaction between 4f and 3d moments is based

on an indirect interaction between the 4f and 3d

spins, which is antiferromagnetic. This, together with

Hund’s rules, explains why the magnetic order is

ferromagnetic in R–T compounds where R is a lighter

element in the series and ferrimagnetic if R is a heav-

ier element (see Alloys of 4f (R) and 3d (T) Elements:

Magnetism).

The way in which the magnetic moment configu-

ration in R–T compounds is affected by a magnetic

field, applied along the principal crystallographic di-

rections of a single crystal, can generally be well de-

scribed in a molecular-field model with two magnetic

sublattices, the R and T sublattices. From such an

analysis, quantitative information on the magnetic

anisotropy (the crystal field interaction) and on the

strength of the 4f–3d interaction can be obtained.

Evidently, such information is most readily obtained

from magnetization measurements on ferrimagnetic

compounds, in which the strict antiparallel configu-

ration of the moments will be affected by a suffi-

ciently high magnetic field.

Single crystals of various classes of R–T com-

pounds with R ¼Co and Fe have become available,

for instance the R

2

T

17

and R

2

T

14

B series, and their

magnetization behavior has been investigated sys-

tematically in high magnetic fields applied along the

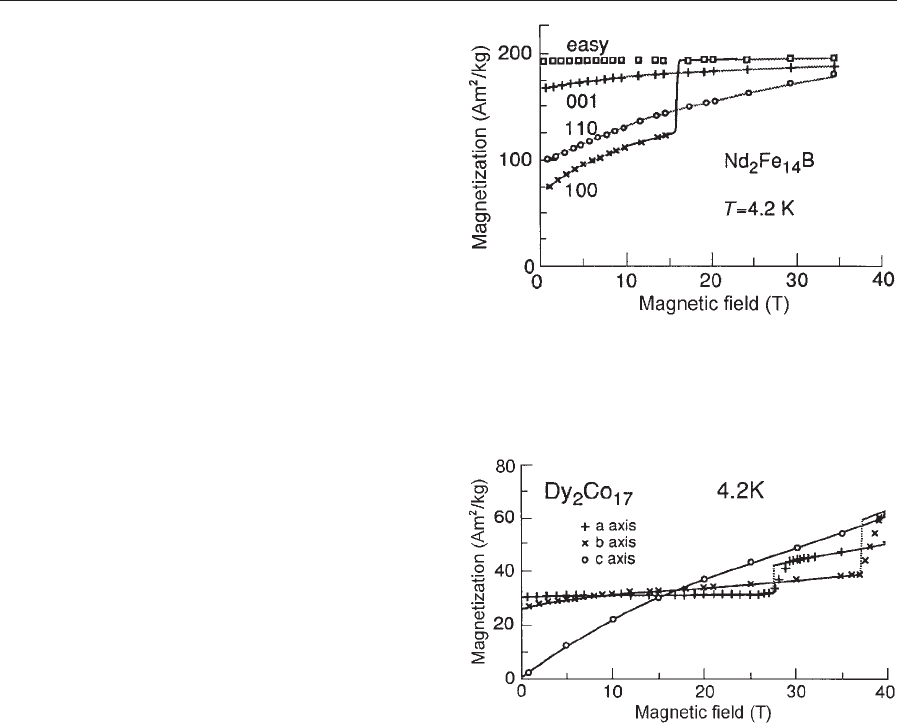

main crystallographic directions. The magnetic iso-

therms at 4.2 K of the ferromagnetic compound

Nd

2

Fe

14

B are shown in Fig. 5. In this compound,

the magnetic moments on the neodymium and the

iron atoms are parallel and the Nd–Fe coupling is

sufficiently strong to keep the moments rigidly cou-

pled in the parallel orientation during the magneti-

zation process. Therefore, the magnetic transition

observed at about 16 T with the field applied in the

[100] direction finds its origin exclusively in the mag-

netic anisotropy. Transitions like this one can be as-

cribed to higher-order terms in the anisotropy or,

equivalently, to higher-order crystal field coefficients

and allow for a rather precise determination of these

parameters. The transition in Nd

2

Fe

14

B is generally

referred to as a first-order magnetization process

(FOMP). In Pr

2

Fe

14

B, two transitions have been

found which are of second-order type (SOMP).

High-field magnetic transitions that are based on

the competition between the strength of the applied

field and the strength of the 4f–3d exchange interac-

tion have been extensively studied on single crystals

of ferrimagnetic R

2

Co

17

and R

2

Fe

17

compounds. As

an example, the magnetization of the hexagonal com-

pound Dy

2

Co

17

is shown in Fig. 6, measured with the

field along the three principal crystallographic direc-

tions. As can be seen, the magnetic anisotropy of

Dy

2

Co

17

is of easy-plane type, the dysprosium mo-

ments lying along the a axis in the basal plane, an-

tiparallel with the cobalt moments, as represented by

Figure 5

Magnetization of Nd

2

Fe

14

B at 4.2 K in magnetic fields

applied along several crystallographic directions

(Buschow 1988).

Figure 6

Magnetization of Dy

2

Co

17

at 4.2 K in magnetic fields

applied along the three main crystallographic directions

(Franse and Radwanski 1993).

751

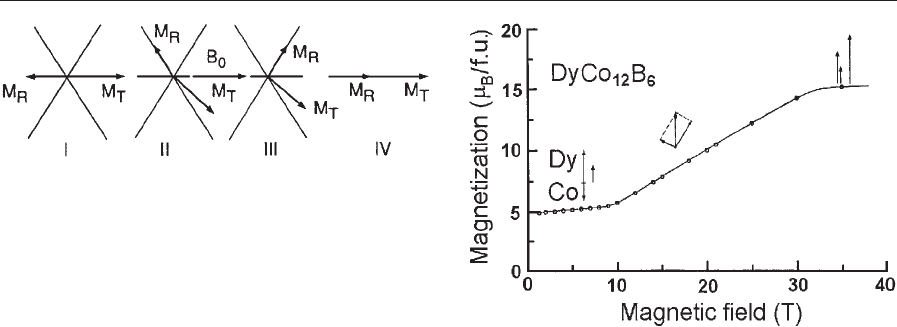

Magnetism: High-field

configuration I in Fig. 7. The resulting magnetization

is constant up to about 28 T and equal to the differ-

ence of the two sublattice magnetizations. At 28 T the

collinear magnetic structure of this ferrimagnet is

broken and a transition takes place to a moment

configuration (II in Fig. 7) in which the dysprosium

moments jump to another easy direction and in which

magnetostatic energy is gained at the expense of ex-

change energy. For the field applied along the b axis,

this transition takes place at a field strength of about

38 T. The solid lines in Fig. 6 correspond to calcu-

lations in terms of a molecular-field model by assum-

ing the existence of two magnetic sublattices, one for

the dysprosium and one for the cobalt moments. On

the basis of the calculations, for the situation with the

field applied along the a axis, in total three transitions

are expected until the parallel, forced-ferromagnetic

arrangement of the two sublattice magnetizations is

reached. When the field is applied along the b axis,

two transitions are expected. Such transitions have

been reported for a large number of compounds of

several series of R–T compounds, such as the R

2

Fe

17

,

R

2

Co

17

, and R

2

Fe

14

B series. Analysis of the magnet-

ization curves has led to knowledge of the crystal field

coefficients for these compounds and has provided

values for the strength of the 4f–3d interaction

(Franse and Radwanski 1993). Also, systematic

trends of these parameters have been established.

An experimental method has also been developed

to measure directly the strength of the 4f–3d inter-

action between the R and the T magnetic moments in

heavy R–T intermetallic compounds. The method

consists of measuring the low-temperature magnetic

isotherms in very high magnetic fields of a single

crystal or of fine single-crystalline powder particles

that can freely rotate in the applied magnetic field.

The free-powder magnetization of DyCo

12

B

6

is

shown as an example in Fig. 8. In this compound,

the breaking of the collinear ferrimagnetic structure

starts at about 10 T. The bending of the sublattice

moments proceeds smoothly up to about 32 T where

the forced ferromagnetic state is reached. The value

of the strength of the Dy–Co exchange interaction

can be obtained by analyzing the observed magnet-

ization during the bending process in terms of a

mean-field description. The very simple magnetiza-

tion process of DyCo

12

B

6

is representative of all R–T

intermetallic compounds, in which the magnetic an-

isotropy of the T sublattice moment is negligible with

respect to the R sublattice anisotropy. For these cas-

es, if the crystal can freely rotate in the applied field,

the R sublattice moment will remain in its easy di-

rection in the crystal during the entire magnetization

process and the magnetization process will be simple.

The magnetization process of DyCo

12

B

6

is very

exceptional in the sense that it is completed in ex-

perimentally accessible fields. In general, even the

value of the field where the bending of the sublattice

moments starts is experimentally inaccessible. How-

ever, because, as the theoretical description tells, this

field is proportional to the difference of the two sub-

lattice moments, the value of this field can be reduced

by carrying out suitable chemical substitutions that

make the values of the two sublattice moments more

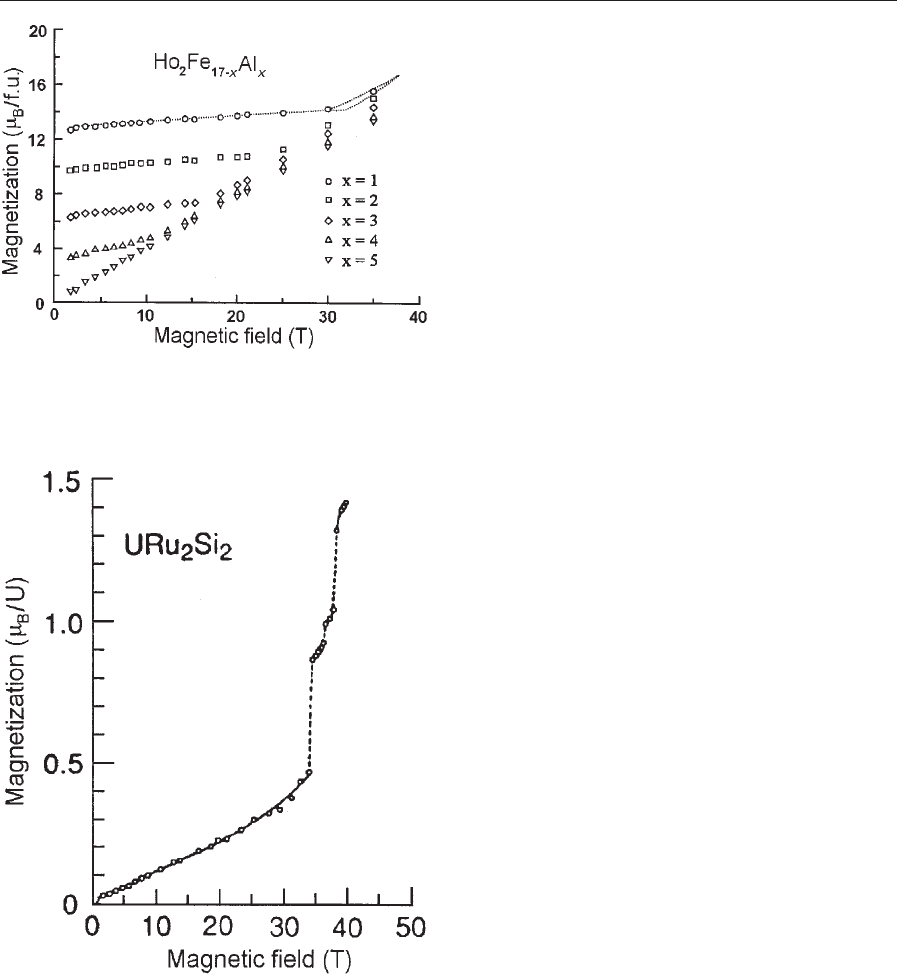

similar. This is illustrated in Fig. 9 for Ho

2

Fe

17

in

which the iron sublattice moment is larger than the

moment of the holmium sublattice and the two sub-

lattice moments can be made more similar by alumi-

num substitution for iron. In this way the bending

process can be brought in an accessible field range,

allowing for the determination of the Ho–Fe

exchange coupling. Systematic trends of the 4f–3d

interaction within and among series of R–T interme-

tallic compounds could be established on the basis of

magnetization measurements on free powders of a

large variety of properly substituted R–T systems

(Liu et al. 1994).

5. 5f Magnetism

Intermetallic compounds that comprise actinides, e.g.,

uranium, are of special interest since the behavior of

Figure 7

Schematic representation of the various moment

configurations in hexagonal ferrimagnetic easy-plane

R

2

T

17

compounds.

Figure 8

Magnetization of free powder of DyCo

12

B

6

at 4.2 K

(after de Boer 1996).

752

Magnetism: High-field

the 5f electrons is intermediate between itinerant

and localized (Sechovsky and Havela 1998). The

magnetism of uranium compounds is characterized

by complex magnetic structures, unstable magnetic

moments, hybridization of the 5f states with d- and

p-electron states of the ligand atoms, and extremely

large anisotropy that can be associated with this hy-

bridization (see 5f Electron Systems: Magnetic Prop-

erties). The magnetization of the antiferromagnet

URu

2

Si

2

(Fig. 10) nicely illustrates the very large an-

isotropy and the richness of field-induced transitions

that are encountered in uranium compounds. More

examples of the high-field behavior of uranium com-

pounds are given in the review of Sechovsky and

Havela (1998).

See also: Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction;

Magnetic Measurements: Pulsed Field; Magnetic

Phase Transitions: Field-induced (Order to Order)

Bibliography

Andreev A V, Bartashevich M I, Goto T, Divis M, Svoboda P

1998 High-field transition in TbCu

2

. In: Clark R G (ed.)

Proc. 5th Int. Symp. on Research in High Magnetic Fields.

North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp. 479–82 (Physica B 246–247,

497–82)

Buschow K H J 1988 Permanent magnet materials based on 3d-

rich ternary compounds. In: Wohlfarth E P, Buschow K H J

(eds.) Ferromagnetic Materials. North-Holland, Amsterdam,

Vol. 4, pp. 1–129

de Boer F R 1996 The magnetization process in free single-

crystalline particles of rare-earth transition-metal com-

pounds. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 159, 64–70

Duc N H, Brommer P E 1999 Formation of 3d-moments and

spin fluctuations in some rare-earth-cobalt compounds. In:

Buschow K H J (ed.) Handbook of Magnetic Materials.

North-Holland, Amsterdam, Vol. 12, pp. 259–394

Franse J J M, Radwanski R J 1993 Magnetic properties of

binary rare-earth 3d-transition-metal intermetallic com-

pounds. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Handbook of Magnetic

Materials. North-Holland, Amsterdam, Vol. 7, pp. 307–501

Gignoux D, Schmitt D 1991 Rare earth intermetallics. J. Magn.

Magn. Mater. 100, 99–125

Gignoux D, Schmitt D 1997 Magnetism of compounds of rare

earths with non-magnetic metals. In: Buschow K H J (ed.)

Handbook of Magnetic Materials. North-Holland, Amster-

dam, Vol. 11, pp. 239–413

Liu J P, de Boer F R, de Chaˆ tel P F, Coehoorn R, Buschow K

H J 1994 On the 4f–3d exchange interaction in intermetallic

compounds. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 132, 159–79

Luong N H, Franse J J M 1993 Magnetic properties of rare

earths Cu

2

compounds. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Handbook

of Magnetic Materials. North-Holland, Amsterdam, Vol. 8,

pp. 415–92

Sechovsky V, Havela L 1998 Magnetism of ternary intermetal-

lic compounds of uranium. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Hand-

book of Magnetic Materials. North-Holland, Amsterdam,

Vol. 11, pp. 1–289

Zvezdin A K 1995 Field induced phase transitions in ferrimag-

nets. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Handbook of Magnetic Ma-

terials. North-Holland, Amsterdam, Vol. 9, pp. 405–543

F. R. de Boer

Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam

The Netherlands

Figure 10

Magnetization of URu

2

Si

2

at 4.2 K in magnetic fields

applied parallel and perpendicular to the c axis

(Sechovsky and Havela 1998).

Figure 9

Magnetization of free powder of Ho

2

Fe

17x

Al

x

compounds at 4.2 K (after Zvezdin 1995).

753

Magnetism: High-field

Magnetization Reversal Dynamics

Many important technological applications involve

reversing magnetic moment in a magnetic material

within a very short time period. For instance, in

computer hard-disk drives, storing a single bit re-

quires reversing the magnetic moments of both the

write transducer and the thin film recording medium

in a fraction of a nanosecond. Understanding mag-

netization reversal dynamics is critical in these appli-

cations (Bertram and Zhu 1992, Mao 2000, Zhu

2001, Zhu and Zheng 2002).

In general, magnetization reversal in a magnetic

material, either of a bulk or thin film, or a particulate

form, is always complex. For studying the reversal

dynamics, there are many experimental means, in-

cluding time-resolved Kerr microscopy field in situ

transmission electron microscopy, field in situ scan-

ning electron microscopy with polarization analysis

(SEMPA), and field in situ magnetic force microscopy

(Hubert and Scha

¨

fer 2000).

Magnetization reversal dynamics can also be stud-

ied via micromagnetic modeling. Combining the

gyromagnetic dynamic equation with the classic mi-

cromagnetic theory (Strikman and Treves 1963,

Brown 1978), the dynamic microscopic magnetiza-

tion reversal process in a ferromagnetic object can be

simulated on a computer or on a cluster of computers

(e.g., Zhu 1989). In the modeling, magnetic energy

density, E, that includes magnetocrystalline aniso-

tropy energy, magnetostatic energy, ferromagnetic

exchange energy, and magnetic potential energy

(Zeeman energy), is calculated at each location of

the object:

E ¼ E

anisotropy

þ E

magneto

þ E

exchange

þ E

Zeeman

ð1Þ

The effective magnetic field exerted on a local

magnetic moment is

H ¼

@E

@M

¼

@E

@M

x

#

e

x

þ

@E

@M

y

#

e

y

þ

@E

@M

z

#

e

z

ð2Þ

1. Gyromagnetic Equations with Energy Damping

Consider a magnetic moment with magnetization M

in a magnetic field H. Due to the fact that magnetic

moment in a magnetic material arises from electron

spin angular momentum and orbital angular mo-

mentum, the magnetic moment precesses around the

field direction, described by the following torque

equation (Landau and Lifshitz 1935):

dM

dt

¼gM H ð3Þ

where g is the gyromagnetic constant. In this process,

the angle between the magnetic moment and the field

remains unchanged. In other words, the energy of

the system is conserved. Any energy dissipation

(or often referred to as energy damping) in the sys-

tem results in a reduction of the angle. To include

energy dissipation, one phenomenological form is the

Gilbert equation:

dM

dt

¼gM H þ

a

M

M

dM

dt

ð4Þ

where M is the magnitude of the magnetic moment

and a is referred to as the damping constant (Gilbert

1955). In this form, the damping motion of the mo-

ment direction towards field direction is viscous. The

above implicit form of the dynamic equation can be

transformed into the following explicit one, known as

the Landau–Lifshitz equation (Landau and Lifshitz

1935):

dM

dt

¼g

L

M H

l

M

M M H ð5Þ

with

g

L

¼

g

1 þ a

2

and l ¼

ga

1 þ a

2

In both Gilbert and Landau–Lifshitz equations,

the magnitude of the magnetic moment is unchanged.

Under the Gilbert equation, if the energy does not

depend explicitly on time, the rate of the energy

change is given by (Zhu 1989)

dE

dt

¼m

0

ag

ð1 þ a

2

ÞM

2

7M H7

2

ð6Þ

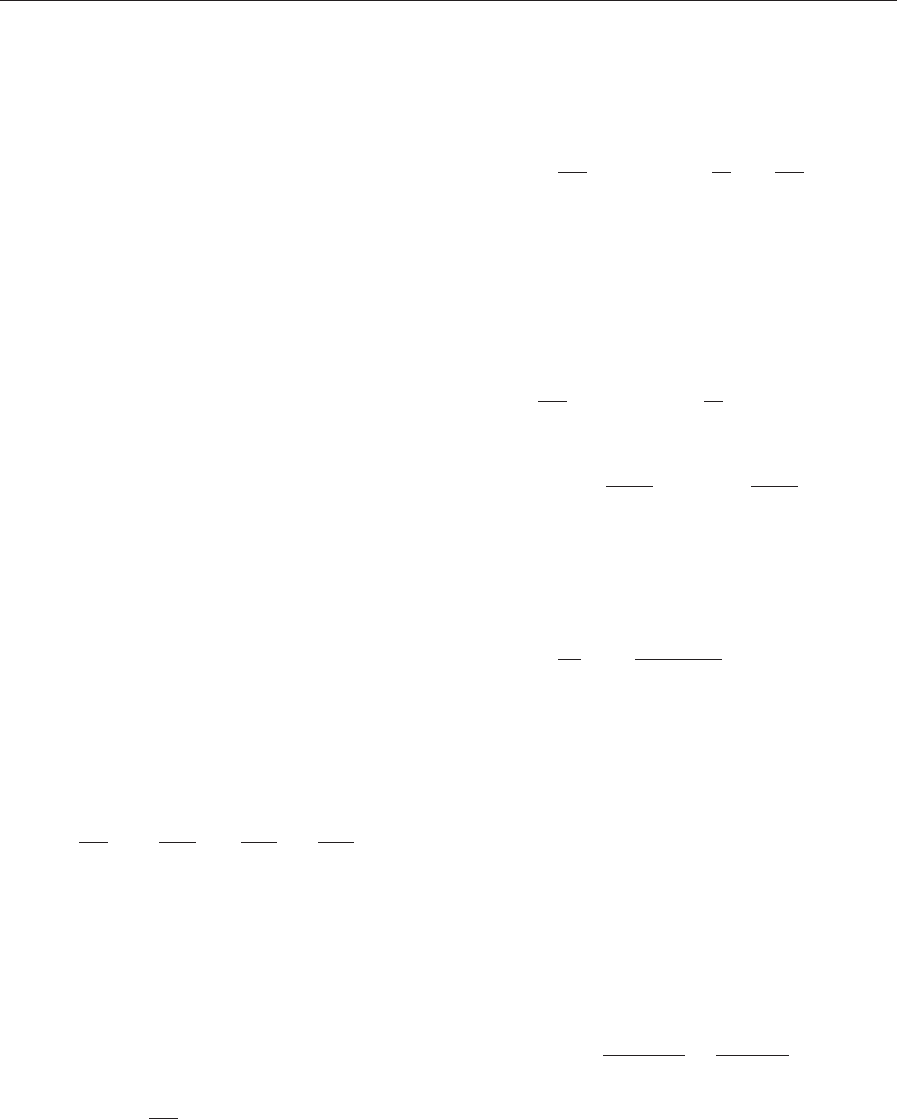

2. Magnetization Reversal of a Uniformly

Magnetized Sphere

Consider a uniformly magnetized single-domain

magnetic sphere in a magnetic field. At nonzero

damping, the magnetic moment of the sphere rotates

towards the field direction while precessing around

the field direction. The smaller the damping constant

a, the greater the number of precession cycles will be

before the magnetic moment aligns with the field di-

rection. Figure 1 shows the calculated trajectories

according to Eqn. (4) for two different values of the

damping constant a. The time duration of the re-

versal, from near antiparallel direction to the parallel

direction, with respect to the field is given by

Dt ¼

1 þ a

2

agðH2H

s

Þ

ln

tanðy

2

=2Þ

tanðy

1

=2Þ

ð7Þ

where y

2

and y

1

are the final and initial angles be-

tween the magnetic moment and the field whose am-

plitude is denoted by H, and H

s

is the switching field

threshold (e.g., the anisotropy field). For a given

magnetic field whose amplitude is greater than the

754

Magnetization Reversal Dynamics

switching field threshold, a ¼1 gives the shortest re-

versal time (Kikuchi 1956).

3. Magnetization Reversal of a Uniformly

Magnetized Thin Film

The dynamic magnetization reversal process in an

always uniformly magnetized magnetic thin film is

quite different than that in an always uniformly mag-

netized sphere. For a magnetization reversal with an

external magnetic field applied in the film plane, the

precession of the magnetic moment around the field

direction causes the magnetization to rotate out of

plane, generating a demagnetization field normal to

the film plane. Subsequently, the magnetization pre-

cesses around this demagnetization field, yielding the

rotation toward the external field direction within

the film plane. Figure 2 shows the trajectories of the

magnetization unit vector for the case of a ¼0 (red

curve) and the case of a ¼0.02 (blue curve). The ro-

tation trajectory of the magnetization vector behaves

very much like a pendulum: at zero damping, the

magnetization swings like an undamped pendulum.

At nonzero damping, the magnetization vector even-

tually rests along the external field direction.

Note that for a uniformly magnetized thin film, it is

the precession of the magnetization that drives the

magnetization reversal in the film plane, in contrast to

the case of uniformly magnetized sphere. The shortest

reversal time for a given external field magnitude

occurs at a relatively small damping constant

depending on the magnitude of the magnetization.

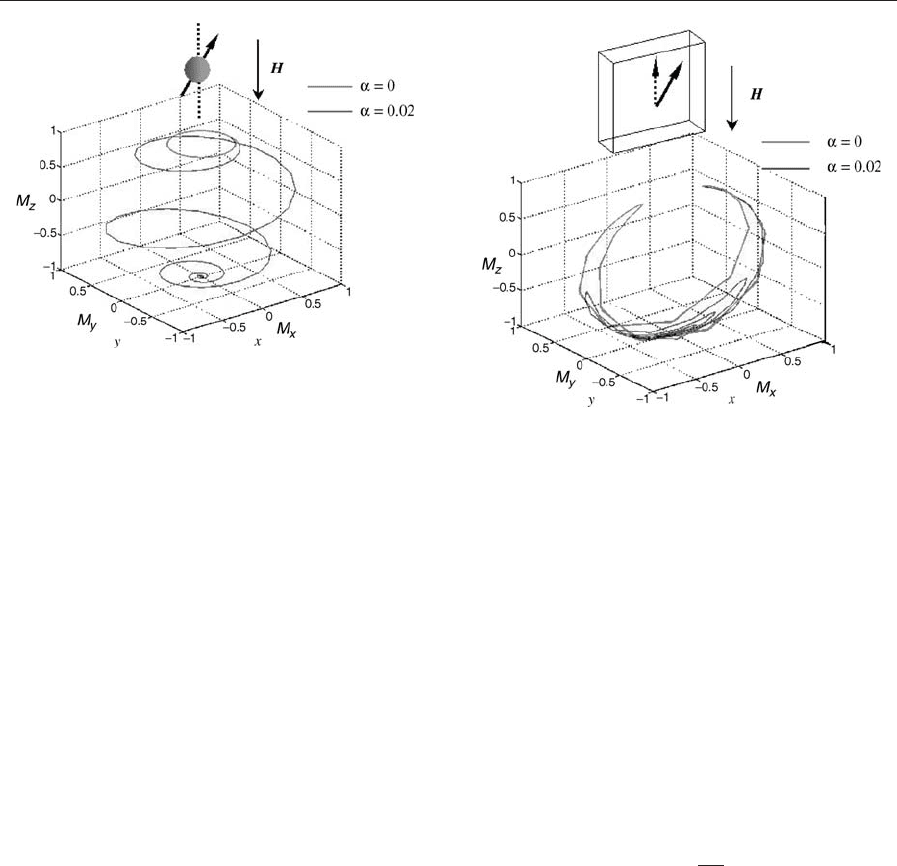

4. Magnetization Reversal of Patterned Mag netic

Thin Film Elements

The two magnetization reversal processes described

in the previous two sections apply only to objects that

have physical dimensions smaller than the exchange

length, defined as the square root of the ratio of

physical dimension significantly greater than the

exchange length:

l

ex

¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

A

M

2

s

s

ð8Þ

where A is the exchange stiffness constant and M

s

is

the saturation magnetization of the material (Brown

1978). For ferromagnetic objects whose physical di-

mensions are greater than the exchange length, the

dynamic magnetization configurations during a mag-

netization reversal are usually spatially nonuniform.

In the case that the ferromagnetic object is a pat-

terned thin film element, the transient reversal pro-

cess becomes almost independent of the damping

constant, except at very final stage of the reversal.

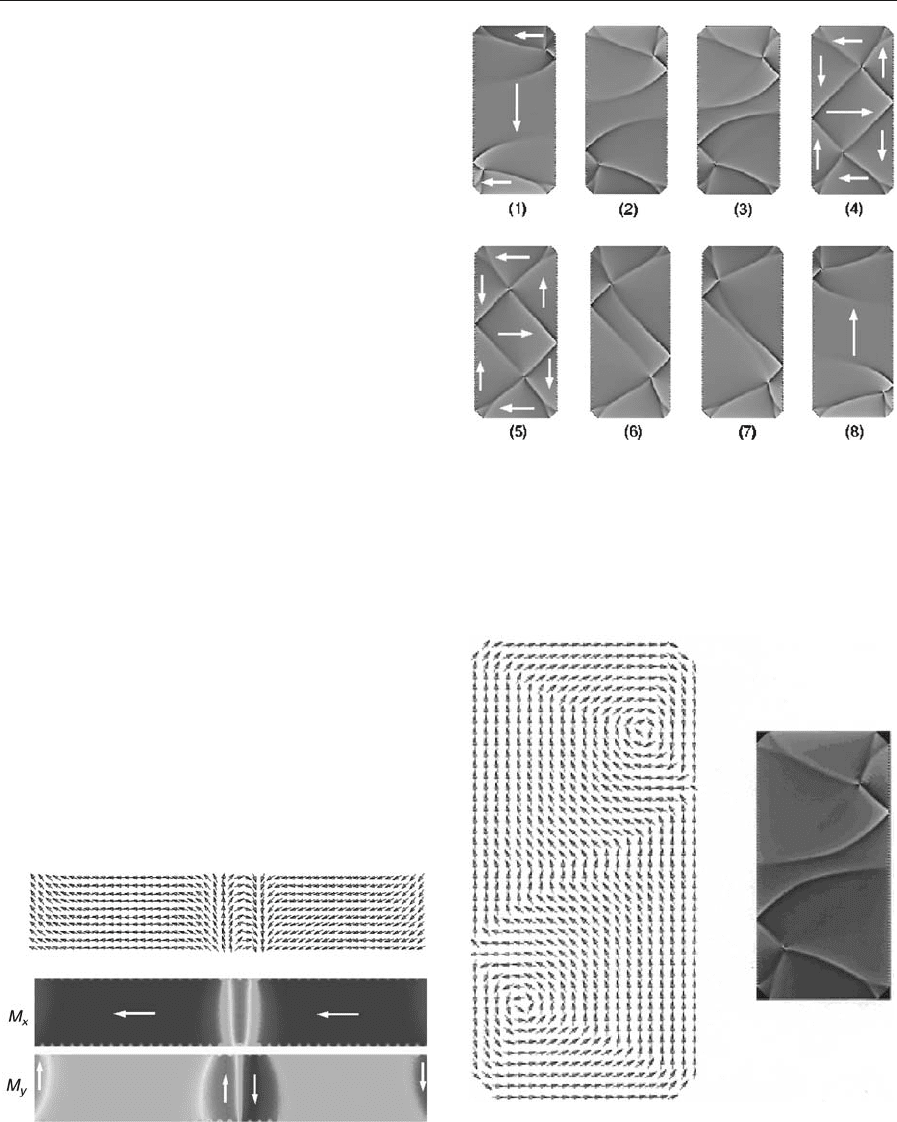

Figure 3 shows a dynamic reversal process for a

Permalloy thin film elliptical element with a length of

0.6 mm, a width of 0.3 mm, and a thickness of 25 nm.

A damping constant a ¼0 has been assumed. The

Figure 1

Magnetization trajectory of a uniformly magnetized

sphere in a magnetic field. With zero damping,

magnetization gyrates around the field direction with a

constant moment-to-field angle, and the energy of

system is unchanged. With the damping constant

nonzero, the magnetization reverses into the field

direction while gyrating around the field direction.

Figure 2

Magnetization reversal of a uniformly magnetized

permalloy (Ni

81

Fe

19

) film for two different values of the

damping constant a. The magnetization reversal is really

driven by the precession motion of the magnetization.

755

Magnetization Reversal Dynamics

external applied field is assumed to rise exponentially

with a rise time t ¼0.1 ns. The reversal starts as

four magnetization vortices nucleate along the edges

of the element, followed by the motion of the vor-

tices transverse to the field direction, across the film

element. As the vortices move out of the opposite

edges of the element, the magnetization of the entire

element has virtually been reversed, except magnet-

ization still precesses, forming a set of spin waves in

the element. Due to the reversal of the magnetization

direction, the Zeeman energy has been reduced.

Since there is no energy damping during the reversal

process, the Zeeman energy has been transformed

into the ferromagnetic exchange energy stored in

the resulted spin waves. The changes of various en-

ergy densities with time during the reversal are plot-

ted in Fig. 4.

The calculation also show that the transient re-

versal process is virtually unchanged if a small energy

damping is introduced during the reversal process

and the reversal time becomes essentially independent

of the damping constant (Fig. 5). The only difference

is that in the case of nonzero energy damping during

the reversal process, no spin wave is generated after

the completion of the reversal.

For a reversal of a thin film element within the film

plane, in the case of zero energy damping, entropy

becomes the driving force of the reversal: the gener-

ation of the spin wave at the end of the reversal re-

sults in an increase of the system’s entropy. Note that

spin wave is an excellent energy reservoir. Further-

more, a spin wave could directly couple to lattice vi-

brations, creating an energy-damping path through

magnon–phonon interactions.

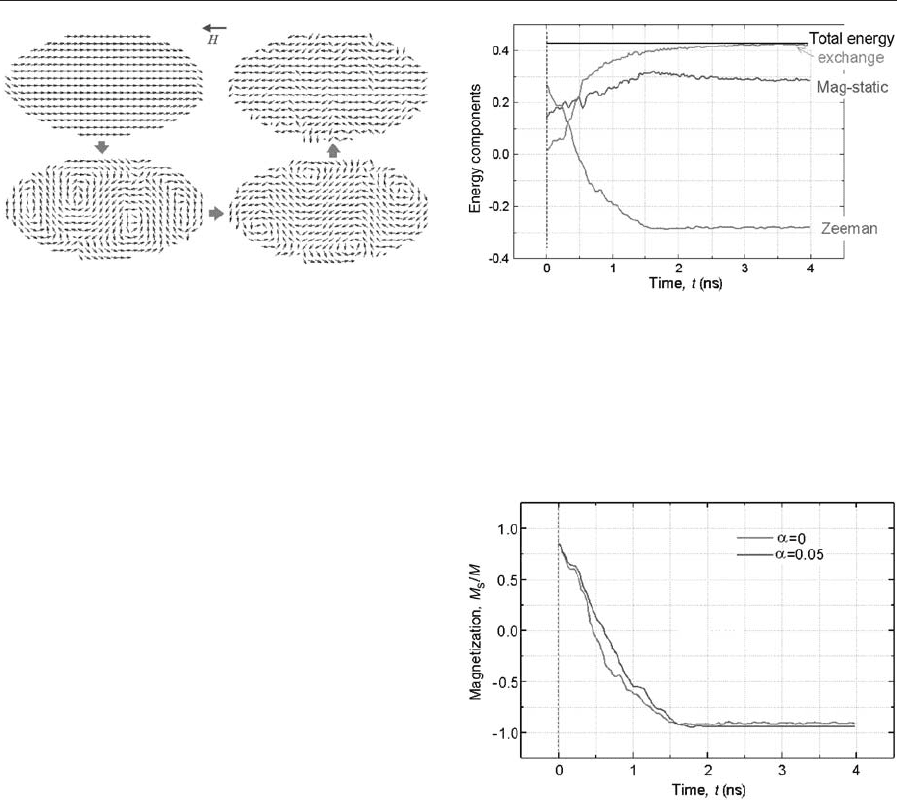

5. Near-uniform Magnetization Switching

The magnetization reversal process described in the

previous section can be characterized as nucleation

and motion of magnetization vortices. The formations

of the vortices are driven by the relatively high mag-

netostatic energy since it is significantly reduced in

a magnetization vortex due to the magnetization flux

closure. When a film becomes sufficiently thin, mag-

netization vortices longer form and the magnetization

reversal becomes near-uniform rotation. Figure 6

shows the magnetization reversal process of a NiFe

film element with a size of 0.5 mm 0.3 mmanda

Figure 3

Calculated magnetization reversal process of an

elliptical permalloy thin film element. The length of the

element is 0.6 mm, width 0.3 mm, and thickness 25 nm.

The reversal starts with the formation of four vortices

along the edges of the element. The four vortices move

across the width of the element, leave magnetization

reversed. At the end, spin waves are generated in the

reversed element.

Figure 4

The dynamic change of various energy densities during

the in-plane magnetization reversal of a patterned

nonsingle domain thin film element with zero energy

damping (a ¼0). The reduction of Zeeman energy

becomes the ferromagnetic exchange energy and

magnetostatic energy stored in the resulted spin waves.

Figure 5

Element-averaged magnetization component along field

direction during a magnetization reversal for two energy

damping constants a ¼0 (red) and a ¼0.05 (blue).

756

Magnetization Reversal Dynamics

Figure 6

Element-averaged magnetization component along field direction during a magnetization reversal for two energy

damping constants a ¼0 (red) and a ¼0.05 (blue).

Figure 7

Formation of a 3601 domain wall during the reversal of a thin NiFeCo film element that is 1.2 mm 0.2 mm in size and

2 nm in thickness. The two rows of color pictures at each stage during the reversal represent the longitudinal and the

transverse magnetization components, respectively (calculated with a ¼0.02).

757

Magnetization Reversal Dynamics

thickness only 6 nm. No vortex is present at any stage

during the reversal.

6. Effect of the Element Ends

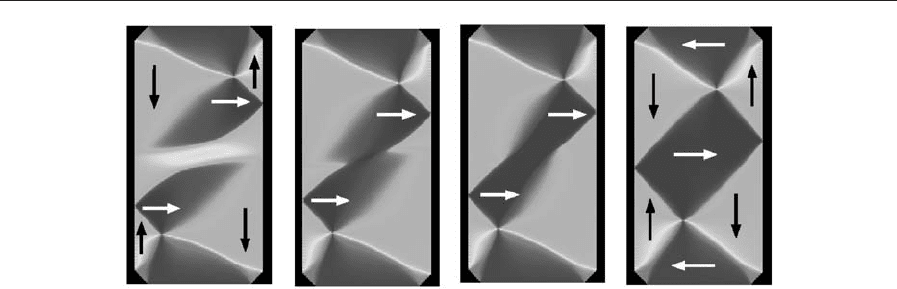

The dynamic magnetization reversal process in a

patterned thin film element strongly depends on

the element’s geometric shape. Reversal of a long

rectangular shaped element is particularly interest-

ing. Figure 7 shows a reversal process in a perm-

alloy element with thickness d ¼2 nm. The length

and the width of the element are 1.2 mm and 0.2 mm,

respectively. The external field is applied along the

element length direction. The magnetizations at

both ends of the element are oriented parallel to

the edges, forming edge domains. The reversal starts

from the two ends and expands into the interior of

the element via motion of the two domain walls.

The magnetization direction within the two domain

walls inherits the magnetization directions of the

two initial edge domains, which are in the opposite

directions in this particular case. As the reversal

progresses, the two domain walls move towards

each other, forming a 3601 domain wall in the mid-

dle of the element. The detailed magnetization con-

figuration of the 3601 domain wall is shown in

Fig. 8. A further significant increase of the field

magnitude is needed to move the 3601 domain walls

out of the side (long) edges. Whereas to reverse the

magnetization back with the presence of the 3601

domain wall, the critical field magnitude becomes

significantly smaller (Fig. 7). The presence of 3601

domain wall in the film element is one of the

important mechanisms causing nonrepeatable mag-

netic switching processes.

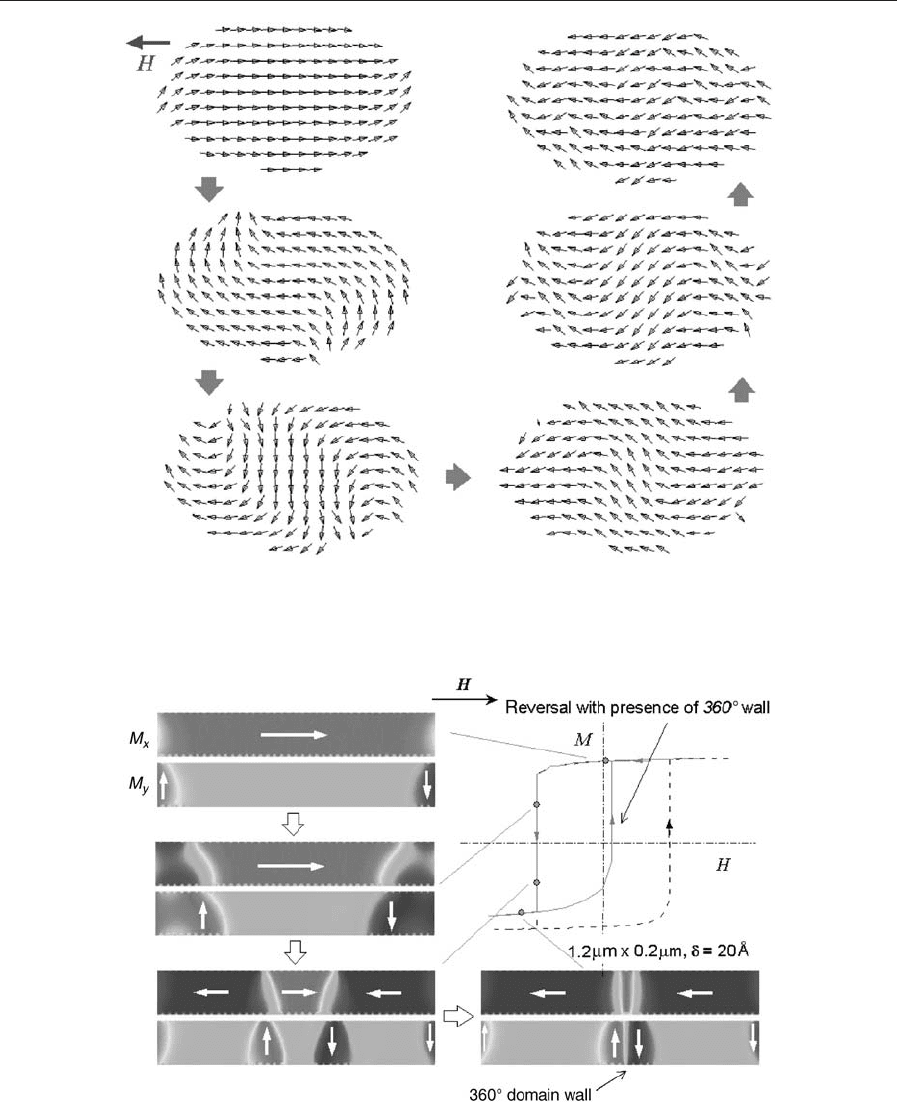

7. Element of Relatively Large Sizes

Figure 9 shows the calculated magnetization reversal

process of a rectangular permalloy thin film element

Figure 8

Detailed magnetization configuration of the 3601

domain wall of Fig. 7.

Figure 9

Simulated magnetization reversal process of a permalloy

film element of size 10 mm 5 mm and thickness 30 nm.

The gray scale represents the magnetization divergence.

An external magnetic field is applied in the element

length direction, opposite to the initial magnetization

(1) in the center of the element.

Figure 10

Magnetization vector configuration of a state during the

reversal shown in Fig. 9 and its corresponding gray scale

representation of the magnetization divergence.

758

Magnetization Reversal Dynamics

with size 10 mm 5 mm and thickness 30 nm. The di-

vergence of the magnetization is plotted in gray scale

to show the domain walls. Figure 10 shows an exam-

ple of the exact magnetization pattern corresponding

to a wall configuration shown in a gray scale plot. As

shown in Fig. 9, from frame (1) to frame (8), the

magnetization of the center of the element is com-

pletely reversed, from pointing down to pointing up.

Prior to the reversal, frame (1) in the figure, there al-

ready exist two triangular domains at the top right and

bottom left whose magnetizations are already in the

reversed (up) direction. As the reversal proceeds, these

two reversed domains expand, forcing the formation

of the diamond transverse domain in the middle of the

element and resulting in the complete flux closure do-

main configuration shown in frame (4). Continued

expansion of the two reverse domains into the entire

central area of the element eliminates the transverse

diamond domain and the reversal is thus completed.

The formation of the closure domain configuration

shown in frame (4) of Fig. 9 is particularly interest-

ing. Figure 11 shows the transient magnetization

configurations from the state shown in frame (3) to

the state shown in frame (4) of Fig. 9. The connection

of the two curved domains forms the central diamond

domain in the closure domain configuration.

8. Summary

Magnetization reversal dynamics can be very compli-

cated even in ferromagnetic objects of simple geometric

shape. The discovery of the giant magnetoresistance,

the advancement of spin-dependent tunneling, and the

exploration of spin in semiconductors have sparked

recent insurgence on the development of many new

types of magnetic devices that utilize magnetic multi-

layer structures patterned into diminutive dimensions.

To facilitate the technological advancements, dynamic

micromagnetic modeling will continue to be a powerful

tool to obtain critically needed understanding of the

magnetization reversal characteristics in these devices

and structures.

See also: Longitudinal Media: Fast Switching; Mi-

cromagnetics: Basic Principles; Micromagnetics: Fi-

nite Element Approach; Magnetic Recording:

Patterned Media; Magnetic Recording Media: Parti-

culate Media, Micromagnetic Simulations

Bibliography

Bertram H N, Zhu J -G 1992 Fundamental magnetization

processes in thin-film recording media. In: Ehrenreich H,

Turnbull D (eds.) Solid State Physics. Academic Press, Vol.

46, pp. 271–371

Brown W F Jr 1978 Micromagnetics. Krieger, Huntington

Gilbert T L 1955 A lagrangian formulation of the gyromagnetic

equation of the magnetization field. Phys. Rev. 100, 1243–53

Hubert A, Scha

¨

fer R 2000 Magnetic Domains. Springer,

pp. 11–104

Kikuchi R 1956 On the minimum of magnetization reversal

time. J. Appl. Phys. 27, 1352–7

Landau L, Lifshitz E 1935 On the theory of dispersion of mag-

netic permeability in ferromagnetic bodies. Physik. Zeitsch.

D. Sowjetunion 8, 153–69

Mao C Y 2000 Micromagnetic modeling of thin film write

heads for magnetic recording. Ph.D. Dissertation, Carnegie

Mellon University, pp. 72–80

Strikman S, Treves D 1963 Micromagnetics. In: Rado G T,

Suhl H (eds.) Magnetism. Academic Press, Vol. 3, pp. 395–414

Figure 11

The transient magnetization configurations showing the dynamic formation of the closure domain pattern during the

magnetization reversal in Fig. 9. The initial (the extreme left) and the final (the extreme right frame) magnetization

states correspond to the states shown in frames (3) and (4) in Fig. 9, respectively. The spectrum of natural light is used

to represent the magnetization component in the horizontal direction, with blue indicating the magnetization pointing

to right and red to the left.

759

Magnetization Reversal Dynamics