Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

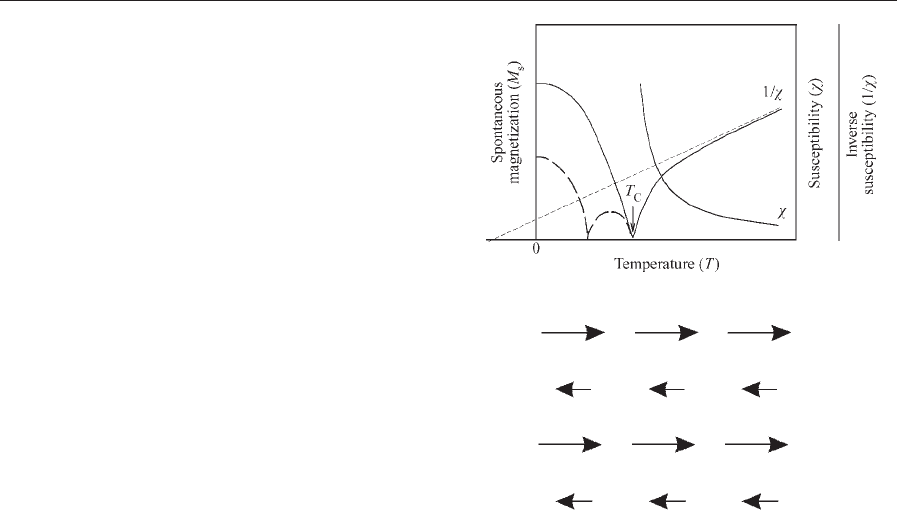

In contrast to ferromagnets, antiferromagnets

exhibit zero spontaneous magnetization (see also

Sect. 3). This is obvious for a simple antiferromagnet

in which pairs of magnetic moments coupled in an

antiparallel manner mutually compensate. The be-

havior of a simple antiferromagnet can be under-

stood within the Ne

´

el model by considering the

antiferromagnet in terms of two interpenetrating

ferromagnetic sublattices A and B with an antipar-

allel coupling of the sublattice magnetizations M

A

and M

B

(7M

A

7 ¼7M

B

7) (Chikazumi 1964, Barbara

et al. 1988).

1.5 Ferrimagnetism

Ferrimagnetism is a term that was originally proposed

by Ne

´

el to describe the magnetic ordering phenomena

in ferrites (see Transition Metal Oxides: Magnetism),

in which Fe ions appear in two different ionic states

and hence bear different magnetic moments with mu-

tual antiferromagnetic coupling. The ferrimagnet can

be considered in a loose analogy as a two-sublattice

antiferromagnet with 7M

A

7 a 7M

B

7. In this context

ferrimagnets appear sometimes in literature under the

name ‘‘uncompensated antiferromagnet’’. As a con-

sequence, a net spontaneous magnetization M

s

( ¼M

A

M

B

) is observed at temperatures below the

ordering temperature T

C

. Various types of M

s

(T)

curves are found for ferrimagnets depending on the

temperature variation of sublattice magnetizations.

Two types of behavior are shown in Fig. 7.

At temperatures well above T

C

, paramagnetic be-

havior is observed with the magnetic susceptibility

following the Curie–Weiss law, usually with a nega-

tive value of Y

p

. At a certain temperature interval

above T

C

, the 1/w vs. T dependence forms a curve as

seen in Fig. 7. This behavior can also be accounted

for within the Ne

´

el sublattice model.

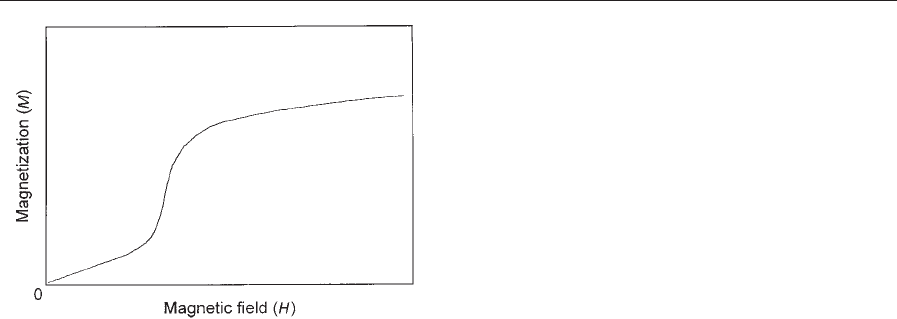

1.6 Metamagnetism

When a sufficient magnetic field is applied to some

materials which exhibit no or a small spontaneous

magnetization an abrupt transition to a high magnet-

ization state may be induced (see Fig. 8) (see also Sect.

5.2). The transition is usually called the metamagnetic

transition (MT) and the high magnetization state is

called metamagnetic because it is a metastable state (it

disappears as soon as the magnetic field is removed).

There are several rather different mechanisms which

cause a MT (see Magnetic Phase Transitions: Field-

induced (Order to Order); Metamagnetism: Itinerant

Electrons; Magnetism: High-field). An important pa-

rameter of metamagnetism is the critical field H

c

at

which the MT occurs (H

c

is usually associated with the

midpoint of the transition). The low field state

(HoH

c

) of a material exhibiting a MT is usually an-

tiferromagnetic, ferrimagnetic, or in some special cases

enhanced paramagnetic.

1.7 Remarks

Note that diamagnetism of filled electronic shells is

an inevitable property of all solids containing atoms

(ions) with some filled electronic shells. In metals

there is also a weak paramagnetic Pauli susceptibility

term (together with the Landau diamagnetic suscep-

tibility) due to conduction electrons that always

contributes to magnetic behavior. These weak sus-

ceptibility contributions are in materials with perma-

nent magnetic moments usually hidden by the much

stronger positive magnetic (paramagnetic, antiferro-

magnetic, ferrimagnetic, ferromagnetic, etc.) re-

sponse. Nevertheless, a proper analysis of magnetic

data requires that the weak diamagnetic and the Pauli

Figure 7

Typical behavior of a ferrimagnet: temperature

dependence of inverse susceptibility at temperatures

above the Curie temperature (T4T

C

) and spontaneous

magnetization M

s

at (ToT

C

). The antiferromagnetically

coupled inequivalent magnetic moments in a

ferrimagnet at ToT

C

are illustrated schematically.

When M

A

bM

B

at all temperatures the M

s

(T) resembles

a ferromagnet (full line). In some materials a special

situation appears due to strongly different temperature

dependencies of sublattice magnetization. In particular,

if 7M

A

7o7M

B

7 for T

comp

oToT

C

, M

A

¼M

B

and

7M

A

747M

B

7 for ToT

comp

(dashed line); at T

comp

,

M

A

¼M

B

, i.e., the sublattice magnetizations

compensate and T

comp

is called the compensation

temperature.

730

Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction

paramagnetic terms are also taken into account when

not completely negligible.

The bulk magnetization is a sum of individual

magnetic moments in the material. Therefore it is

obvious that the knowledge of magnetic field and/or

temperature dependence of the magnetization (sus-

ceptibility) allows only rather limited and frequently

ambiguous conclusions to be reached concerning de-

tails of the arrangement of magnetic moments, their

dynamics, relation to electronic structure, etc. Real-

istic studies of microscopic aspects of magnetism re-

quire the application of methods that use local probes

to sense phenomena in the material on the micro-

scopic scale.

Traditionally, the most frequently used micro-

scopic methods in magnetism, especially powerful in

studies of magnetic structures and magnetic excita-

tions, are based on various aspects of neutron scat-

tering in materials (Bacon 1975, Squires 1978,

Barbara et al. 1988) (see Magnetism: Applications of

Synchrotron Radiation). These experiments are made

possible by intensive stationary or pulsed beams of

thermal or cold neutrons available at large neutron

facilities. Representative examples of reactor based

facilities (most of which are open to the external user

community) are the Institute-Laue-Langevin (ILL),

(http://www.ill.fr), JAERI (http://www.jaeri.go.jp),

NIST Research Center (http://rrdjazz.nist.gov/),

Oak Ridge, Chalk River Laboratories (http://neu-

tron.nrc.ca/), and Hahn-Meitner-Institut (http://

www.hmi.de).

Spallation sources provide high-intensity pulsed

neutron beams at various facilities: ISIS (http://www.

isis.rl.ac.uk/), LANSCE (http://lansce.lanl.gov), IPNS

(http://www.pns.anl.gov/), and SINQ at PSI (http://

www1.psi.ch).

Excellent complementary microscopic tools are of-

fered by rapidly developing methods based on x-ray

scattering in magnetic materials (see Magnetism: Ap-

plications of Synchrotron Radiation). These methods

have developed as a result of the high-intensity x-ray

beams produced at the most powerful synchrotron

facilities, e.g., ESRF (http://www.esrf.fr), NSLS

Brookhaven National Laboratory (http://www.nsls.

bnl.gov/), and SPRING-8 Himeji.

Fundamental microscopic experiments revealing

direct connections between electronic structure and

magnetism can be performed using advanced photo-

emission methods (see Photoemission: Spin-polarized

and Angle-resolved).

Mo

¨

ssbauer spectroscopy and other methods stud-

ying hyperfine interactions, such as NMR, NQR

(nuclear quadrupole resonance), and PAC (perturbed

angular correlations) (Cahn and Lifshin 1993) (see

Perturbed Angular Correlations (PAC)), allow the

study of magnetic systems probed by a hierarchy of

nuclear energy levels which is established partly as a

result of hyperfine interactions between the nucleus

and the electronic system. Methods exploiting muon

spin rotation and relaxation ( mSR) offer unique pos-

sibilities to observe very small magnetic moments

on a level of 10

2

m

B

as well as various aspects of

dynamics of magnetic systems (Schenck and Gygax

1995) (see Muon Spin Rotation (mSR): Applications

in Magnetism).

The rapid development of theoretical methods and

computer codes and the concomitant increase in ca-

pacity and speed of modern computers have made

realistic ab initio calculations of the electronic struc-

ture of magnetic materials widely available. Predic-

tions made by such calculations have motivated new

experiments focused on particular problems (Brooks

and Johanson 1993, Sandratskii 1998) (see Density

Functional Theory: Magnetism).

2. Magnetic Moments of d and f Transition

Elements

An atom (ion) has a net magnetic moment when an

inner d-orf-electron shell is incomplete such that the

individual electronic moments within the shell do not

cancel completely. In the Periodic Table there are five

groups of elements in which this incomplete cancel-

lation occurs: the iron group (3d ), the palladium

group (4d ), the rare earth (or lanthanide) group (4f ),

the platinum group (5d ), and the actinide group (5f ).

Free-atom d and f electrons possess magnetic mo-

ments (Kittel 1976, Ashcroft and Mermin 1988) that

are predicted based on the principles of quantum

mechanics (see Transition Metal Oxides: Magnetism

and Localized 4f and 5f Moments: Magnetism). When

an atom (ion) of a transition element is embedded in

a solid, these moments often disappear when the

electron orbitals overlap and bond, which leads to

delocalization of the d or f electrons—the electrons

become itinerant. Metallic or covalent bonding is

Figure 8

Typical magnetic field dependence of magnetization of a

material exhibiting metamagnetism.

731

Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction

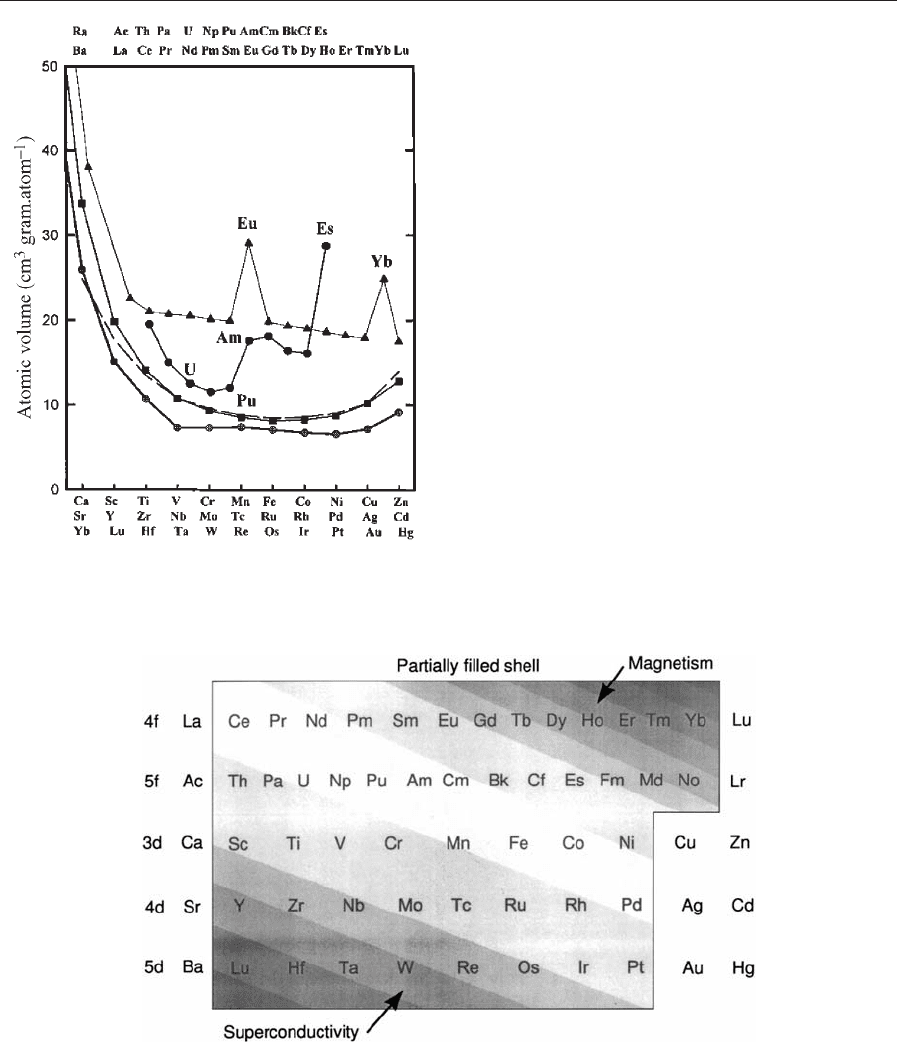

inconsistent with magnetic moments that mostly arise

from localized electrons. Onset of this bonding is

clearly reflected in a decrease in atomic volume. This

effect is well seen in Fig. 9 for transition metals (3d,

4d, and 5d ). In the first part of the respective series

the bonding states are gradually populated and the

ion volume decreases. In the second part the popu-

lation of antibonding states is associated with a grad-

ual increase in volume. The very weak ion volume

variation across the 4f series is consistent with local-

ized behavior of 4f electrons in most of the lanthanide

ions. The actinide series (5f) provides an excellent

natural example of the crossover between the itiner-

ant character of 5f states in elements from thorium to

neptunium and localized behavior for these beyond

plutonium.

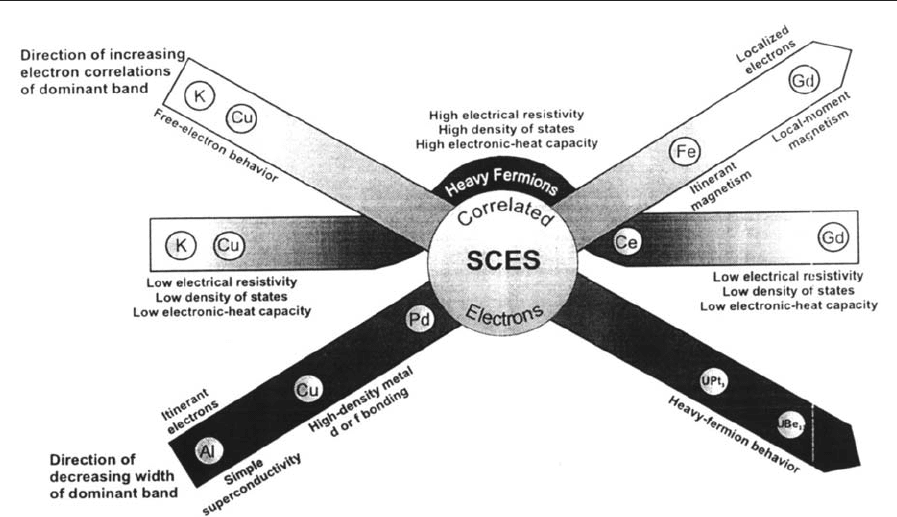

An instructive representation of the evolution of

magnetism within the transition-element series be-

tween the itinerant and localized character of the d

and f electrons has been presented by Smith and

Kmetko (1983) in the ‘‘periodic table of transition

elements’’ (see Fig. 10). Note that the sequence of

rows in the table is different from the Periodic Table

of elements; in particular the series of f elements is

placed above the transition metal series. The lower

left section of the table comprises elements in which

the d and 5f electrons strongly participate in bonding

and are itinerant in character. Most of these materials

are superconducting. In the top right segment the

majority of lanthanides and heavy actinides are lo-

cated which exhibit localized f-electron magnetism.

Figure 9

Evolution of atomic volume across 3d (hexagons), 4d

(squares), 5d (dashed line), 4f (triangles), and 5f (circles)

transition metal series.

Figure 10

A revisited periodic table of the f and d transition element series. The periodic table is rearranged with the rare-earth,

or lanthanide elements on the top row, the actinides in the second row, and the d-electron transition metals below

them. Most metals have predictable ground states and become magnetic or superconducting as the temperature is

lowered below a characteristic temperature of magnetic ordering or superconducting transition. The low-temperature

metallic properties of the elements along the diagonal are difficult to explain because, in the solid-state, their f or d

valence electrons are poised between localization and itinerancy (after Smith and Kmetko 1983).

732

Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction

This together with Fig. 9 suggests that the cross-

over to localized behavior can be roughly marked by

the diagonal white (and nearly white) region. Cross-

ing this region from left to right can be viewed as a

Mott transition from a metallic state to an insulating

magnetic state for the relevant d and f electrons. The

cross-over region can be moved to the left or right by

embedding ions in appropriate compounds (or by

applying external pressure) which yields a reduced or

increased overlap of the d-orf-electron wave-func-

tions. The transition-metal d electrons then appear to

be localized and bear magnetic moments as a rule in

insulators (see Transition Metal Oxides: Magnetism

and Pnictides and Chalcogenides: Transition Metal

Compounds). On the other hand, itinerant nonmag-

netic 4f electrons are found in some specific materials

like CeFe

2

(Ericksson et al. 1988).

The magnetism of localized electron states can be

treated theoretically and the observed magnetic mo-

ments usually compare well with the calculated values.

Nevertheless, the moments of localized electrons in

solids may be considerably reduced, due mainly to

crystal field interaction, which is particularly effective

where there are electrons with larger spatial extensions

of wave-functions (see Localized 4f and 5f Moments:

Magnetism). Also, the itinerant electron states that

form energy bands may, under certain conditions,

yield magnetic moments and magnetic ordering (see

Itinerant Electron Systems: Magnetism (Ferromagnet-

ism),andMetamagnetism: Itinerant Electrons).

One of the important control parameters is the

relevant bandwidth that plays an important role in

determining the type of ground state and the possi-

bility of metamagnetic state of an itinerant electron

system. In the cross-over region between localized

and itinerant behavior narrow-band materials are lo-

cated, which are characterized by strongly correlated

electrons (see Electron Systems: Strong Correlations).

The specific electronic properties of strongly corre-

lated electron systems (SCES) in the context of the

broad spectrum of metallic systems are schematically

summarized in Fig. 11. In the cross-over region a

number of exotic phenomena is also frequently ob-

served, for example, the heavy-Fermion behavior (see

Heavy-fermion Systems) and the intermediate-valence

behavior (see Intermediate Valence Systems).

The variety of observed magnetic phenomena con-

nected with various stages of ‘‘magnetic’’ electron

states between localized and itinerant causes prob-

lems in formulating a unified theory of magnetism

in materials. Reasonable theoretical approaches are

available for the extreme cases: the magnetism of lo-

calized electrons (see Transition Metal Oxides: Mag-

netism) and magnetism of itinerant electrons. The

intimate relationship between magnetism and elec-

tronic structure points to the necessity of applying, in

magnetism, methods based on electronic structure

theories. The density functional theory (Brooks and

Johanson 1993) has been proven to be very successful

in providing realistic ab initio electronic structure

calculations in studies of numerous materials (see

Density Functional Theory: Magnetism).

3. Ordering of Magnetic Moments

In Sect.1 ferromagnetism, antiferromagnetism, and

ferrimagnetism were introduced phenomenologically.

These phenomena are based on long-range ordering

of magnetic moments in materials. There are two

necessary ingredients of magnetic ordering—magnetic

moments and exchange interactions. The latter deter-

mine the intersite correlations of magnetic moments.

3.1 Exchange Interactions

The prototype of exchange interaction is the interac-

tion that correlates spins in the hydrogen molecule.

(The description can be found in most textbooks on

quantum mechanics.) These interactions are electro-

static in origin and lead to a splitting of the energies of

the antisymmetric and symmetric orbital states and

hence the symmetric (mm) and antisymmetric (mk)spin

states. This is the case for all exchange interactions.

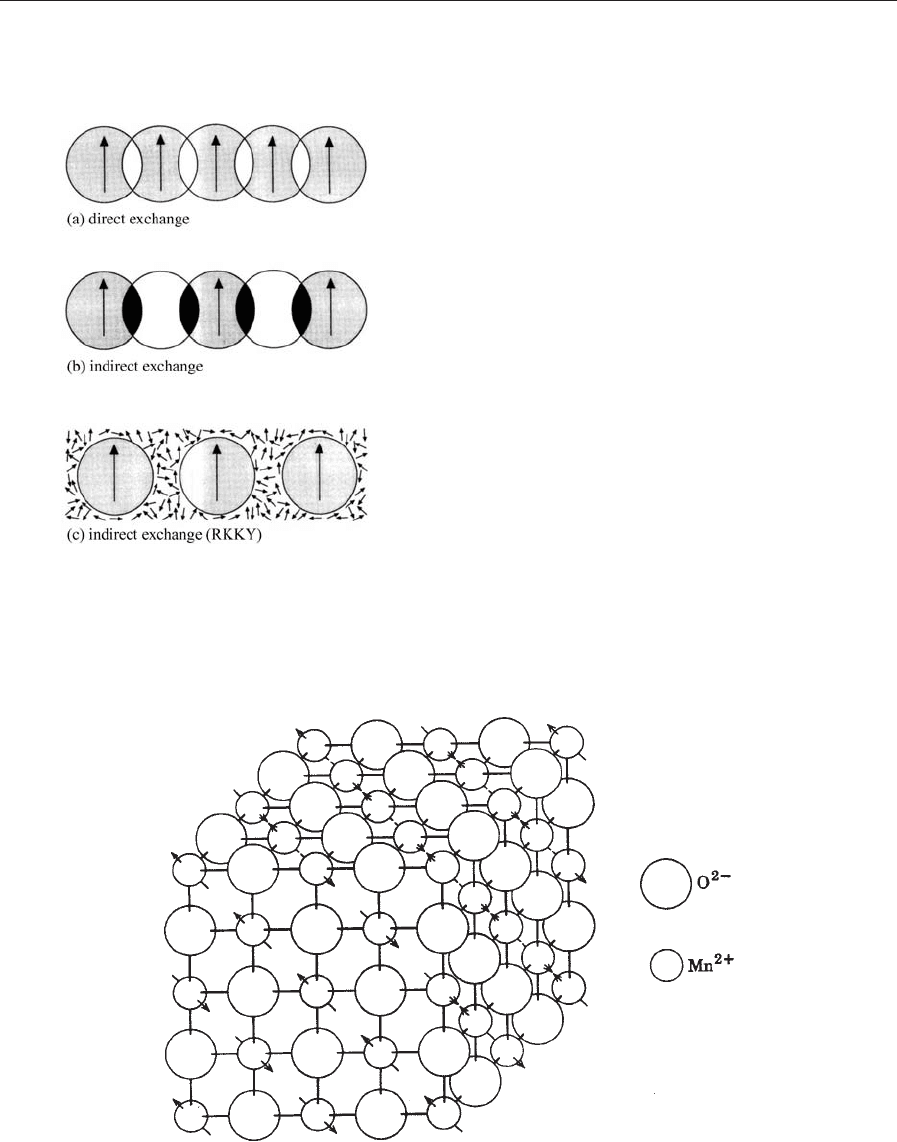

In Fig. 12 the main types of exchange interactions

are reviewed in a schematic illustration. If the

magnetic atoms are nearest neighbors in a lattice

the direct exchange interaction (nearest-neighbor in-

teraction) can be effective in the case of a sufficient

overlap of the relevant d or f orbitals. The best ex-

amples of a direct exchange interaction can be found

in the ferromagnetic 3d metals Fe, Co, and Ni, which

order at high temperatures (see Table 1) but exhibit

magnetic moments that are considerably reduced

compared with the free-ion values.

In alloys and compounds the magnetic moment-

carrying ions are frequently separated by other

atoms, allowing various types of weaker indirect ex-

change interactions to become effective. The weak

RKKY interaction between two magnetic atoms

in metallic materials is mediated by the conduction

electrons polarized when appearing in the vicinity of

a magnetic ion (Jensen and Mackintosh 1991) (see

Localized 4f and 5f Moments: Magnetism). Owing to

properties of the conduction electrons the RKKY

interaction is long-range and oscillates with respect

to the distance from the magnetic ion. As a conse-

quence, the ordered arrangements of magnetic

moments (magnetic structures) determined predom-

inantly by the RKKY interaction are complex and

have long periodicity in some directions. This type of

interaction plays a principal role in the magnetic or-

dering of highly localized electrons bearing magnetic

moments, which are typically found in lanthanides

and their compounds. The 4f moments in these

materials are, as a rule, large and compare well with

the free-ion moments but the relevant ordering

temperatures are rather low (see GdNi

2

in Table 1).

733

Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction

The super-exchange interaction is typical for ma-

terials in which the magnetic atoms are surrounded

by ligands that do not carry permanent magnetic

moments. It has been introduced to describe a situ-

ation in magnetic oxides and can be applied to similar

ionic materials. A typical example is MnO in which

Mn

2 þ

ions are separated by an O

2

ion. The crystal

and magnetic structure of MnO is shown in Fig. 13.

The essential ingredient of super-exchange interac-

tion in oxides is that the spin moments of the metal

ions on opposite sides of an oxygen ion interact with

each other through the p-orbit of the oxygen ion

(Chikazumi 1964, Barbara et al. 1988) (see Transition

Metal Oxides: Magnetism).

A particular analogy of super-exchange is the

indirect exchange in intermetallic materials called

‘‘hybridization-mediated exchange interaction’’

which is frequently reported in actinide intermetal-

lics (Sechovsky´ and Havela 1998). In this case the

interaction between two magnetic ions is mediated by

polarization of the valence states of an ion between

them (ligand) due to hybridization of relevant mag-

netic ion and ligand states. Consequently a non-

negligible magnetic moment is also observed on the

originally nonmagnetic atom (ion).

The idea of a double exchange interaction (Kubo

and Ohata 1972) has been introduced to explain

ferromagnetism in some perovskite systems contain-

ing ions that may possess two different ionic states at

crystallographically equivalent sites. The double ex-

change mechanism became an important issue of the

manganese-containing perovskites exhibiting colossal

magnetoresistance.

Generally the exchange interaction energy between

two ions can be expressed as:

H

ij

¼2J

ij

#

S

i

#

S

j

ð9Þ

Figure 11

Strongly-correlated electron systems (SCES) at a crossover of electronic properties. The figure summarizes some of the

unusual electronic properties of SCES, stemming from the dominant role of their narrow d-orf-band. Along one

diagonal, they stand midway between simple metals, whose conduction electrons are essentially uncorrelated and

which exhibit free-electron behavior, and heavy-fermion materials, whose conduction electrons exhibit very strong

correlations leading to extremely high effective electron masses. Along the other diagonal, SCES stand at the

crossover between materials whose itinerant broad-band electrons form superconducting ground states and magnetic

materials, whose fully localized electrons (infinitely narrow band) form local magnetic moments and magnetic ground

states. Along the horizontal line, SCES materials are distinguished from the elements on either side by their high

resistivity and specific heat, high density of electron states at the Fermi energy, and enhanced electronic mass. Smith

and Boring (2000) have presented such a figure originally to point out the electronically unique Pu (plutonium), an

actinide metal with strongly correlated 5f electrons.

734

Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction

where J

ij

is the exchange integral (10

2

–10

3

K for direct

exchange in 3d metals, 10–10

2

K for indirect ex-

change and super-exchange), and

#

S

i

;

#

S

j

are spin op-

erators of the ith and the jth ion. For the whole

system we have the exchange interaction expressed

by:

H

ij

¼

X

i;j

iaj

J

ij

#

S

i

#

S

j

ð10Þ

A convenient expression for an exchange interac-

tion is obtained in terms of the molecular field H

m

.

The energy of exchange interactions of an ion with

the other ions in a solid can be formally replaced by

the energy of the ion’s magnetic moment in an ex-

ternal magnetic field, H

m

, which is called the molec-

ular field (also mean field). The molecular field is

proportional to the spontaneous magnetization

(domain magnetization or sublattice magnetization)

such that

H

m

¼ lM ð11Þ

where the molecular field constant l is determined by

the strength of the exchange interaction.

For example, the molecular field in iron at room

temperature is 6.8 10

8

Am

1

, which is equivalent to

a magnetic induction of 855 T. Introduction of the

molecular field allows the theory of magnetization

(susceptibility) behavior of ferromagnets, antiferro-

magnets, and ferrimagnets to be developed easily

(Chikazumi 1964, Barbara et al. 1988, Gilles 1994)

(see Localized 4f and 5f Moments: Magnetism). The

Curie temperature for a ferromagnet or ferrimagnet,

as well as the Ne

´

el temperature for an antiferromag-

net, is a measure of the sum of the absolute value of

molecular-field coefficients (Barbara et al. 1988).

Figure 12

Schematic illustration of the main types of exchange

interactions (direct, indirect—super-exchange or

hybridization-mediated exchange interaction, and

RKKY-type indirect exchange interaction mediated by

polarized conduction electrons).

Figure 13

Crystal and magnetic structure of MnO.

735

Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction

3.2 Types of Magnetic Ordering: Magnetic

Structures

The character of long-range ordering of magnetic

moments is reflected in a magnetic structure that has

a certain translational symmetry of equivalent mag-

netic moments (in analogy to the crystal structure).

To determine fully the magnetic structure of a par-

ticular material, four basic facts need to be estab-

lished (Rossat-Mignod 1987):

(i) the ordering temperature below which the mag-

netic moments develop some type of long-range order

(ferromagnetic, or another ordering yielding a spon-

taneous magnetization, below T

C

or antiferromag-

netic below T

N

);

(ii) the wavevector q that characterizes the modu-

lation of magnetic moments within the structure. If q

is equal to the reciprocal lattice vector of the under-

lying crystal structure, or if it is a simple fraction

thereof, the structure is called commensurate. The

other magnetic structures are called incommensurate.

The incommensurate collinear structure is usually

transformed to a commensurate one at low temper-

atures. Magnetic structures that should be described

by more than one q-vector are called ‘‘multi-q’’ struc-

tures (Bacon 1975, Barbara et al. 1988);

(iii) the orientation of magnetic moments with re-

spect to the crystallographic axis and mutual orien-

tation of neighboring magnetic moments. In this

respect a large variety of noncollinear magnetic struc-

tures (in which magnetic moments on at least some

neighboring magnetic sites are neither parallel nor

antiparallel) has been observed besides the collinear

structures (in which magnetic moments on neighbor-

ing magnetic sites are only either parallel or antipar-

allel);

(iv) the magnitude of the magnetic moment on

each ‘‘magnetic’’ site.

The noncollinear structures usually appear as a re-

sult of competition between exchange interactions and

the magnetocrystalline anisotropy. Besides extensive

experimental investigations of noncollinear magnetic

structures using neutron scattering, a theoretical ap-

proach using the density functional theory provides

realistic results for many systems (Sandratskii 1998).

Long-period magnetic structures appear due to the

long-range oscillatory character of exchange interac-

tions, e.g., RKKY-type. The magnetic moments may

be rotating, precessing (helical structure), or collinear

but modulated with a period given by q. Incommen-

surate magnetic structures frequently occur due to

exchange interactions being strong in only two di-

mensions while the exchange interaction along

the third direction is much weaker. In this case the

incommensurate structure emerging below T

N

is re-

placed by a commensurate ordering at lower temper-

atures.

Effects of RKKY-type interaction are illustrated

by the variety of magnetic structures in rare-earth

metals (Barbara et al. 1988, Jensen and Mackintosh

1991), ranging from ferromagnetism, e.g., the ground

state of dysprosium, to various long-period modu-

lated or spiral structures, e.g., erbium (see Localized

4f and 5f Moments: Magnetism ).

4. Magnetic Phase Transitions

A material that exhibits a long-range magnetic or-

dering at low temperatures in zero magnetic field is

characterized by at least two phases: the high-tem-

perature paramagnetic phase and the magnetically-

ordered ground-state phase. In simple systems, the

ground-state phase is established immediately below

the magnetic-ordering temperature (T

C

or T

N

). Fre-

quently, the magnetically ordered phase, which ap-

pears at temperatures below T

C

(or T

N

), is different

from the ground-state phase. Then one or more mag-

netic phase transitions are observed at temperatures

below T

C

(or T

N

).

When applying an external magnetic field new

magnetic phases can be induced. These phases are

usually called metamagnetic and the related mag-

netic phase transitions with respect to the external

magnetic field as the control parameter are called

metamagnetic transitions. These transitions are

observed in various real antiferromagnets and ferri-

magnets (see Magnetic Phase Transitions: Field-

induced (Order to Order)).

Metamagnetic phase transitions from a paramag-

netic state to a magnetically ordered phase can

also be found in nearly magnetic itinerant electron

systems (Fig. 6) (see Metamagnetism: Itinerant Elec-

trons). Further examples can be found in review pa-

pers on magnetism in rare-earth intermetallic

compounds (Gignoux and Schmitt 1991, 1995) and

uranium intermetallics (Sechovsky´ and Havela 1998).

New magnetic phases and magnetic phase transi-

tions may also be induced by applying external pres-

sure (Sechovsky´ and Havela 1998) or by controlled

variation of the material composition (see Magnetic

Systems: External Pressure-induced Phenomena). In

the cross-over region between magnetic ordering and

the nonmagnetic state rather unusual phenomena are

observed at low temperatures (see Heavy-fermion

Systems).

A phase transition between two magnetic phases

can be a first-or second-order type depending on

whether it is connected with a discontinuity of the

first derivative (e.g., magnetization) or the second

derivative (e.g., magnetic susceptibility) of the mag-

netic part of the free energy, respectively. Magnetic

phase transitions in real materials are usually also

reflected in transport properties (Sechovsky´ and

Havela 1998) (see Intermetallics: Hall Effect, Elemen-

tal Rare Earths: Magnetic Structure and Resistance,

Correlation of; Magnetoresistance: Magnetic and

Nonmagnetic Intermetallic; Giant Magnetoresistance:

736

Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction

Metamagnetic Transitions in Metallic Antiferromag-

nets, and Rare Earth Intermetallics: Thermopower of

Cerium, Samarium, and Europium Compounds) and in

thermodynamic and other material properties (see

Magnetic Systems: Specific Heat; Magnetocaloric

Effect: From Theory to Practice; and Magnetoelastic

Phenomena).

4.1 Magnetic Phase Diagrams

A magnetic phase diagram is a schematic represen-

tation of phases adopted by a material over a range

of varying parameters. Parameters are usually tem-

perature (T ) and external magnetic field (H ), exter-

nal pressure (p), or the concentration of a substituting

element (x). These are referred to as H–T, p–T,or

x–T magnetic phase diagrams, respectively. Magnetic

phase diagrams of simple magnetic systems can con-

tain only two phases: the paramagnetic phase and

one magnetically ordered phase. In the case of several

competing interactions, especially long-range inter-

actions, the relevant magnetic phase diagram may be

rather rich on different phases.

In strongly anisotropic magnetic systems a com-

plete description requires up to three different mag-

netic phase diagrams, one each for the magnetic fields

applied along the three principal crystallographic

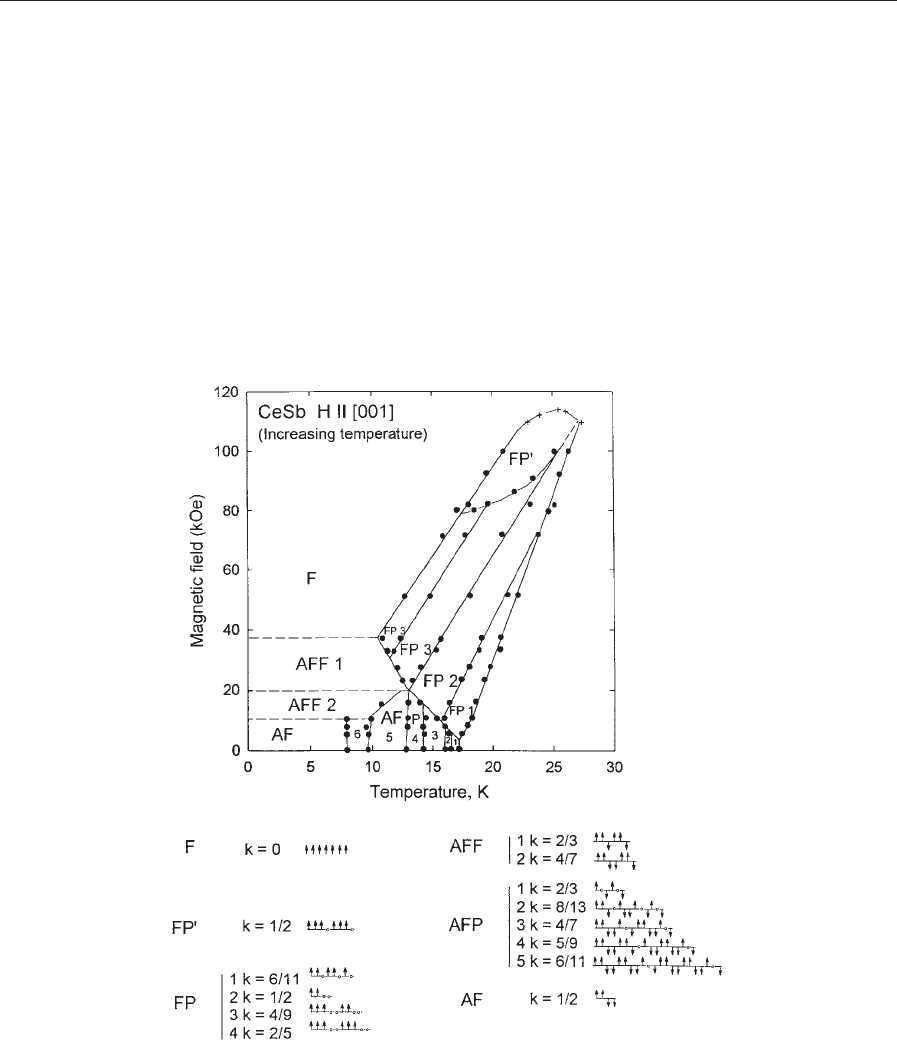

directions. The compound CeSb (Rossat-Mignod

et al. 1983, 1990), which crystallizes in one of sim-

plest crystal structure—the cubic NaCl-type, is an

excellent example of a very complicated magnetic

phase diagram. The enormous number of magnetic

Figure 14

Magnetic phase diagram of CeSb. Orderings in the 15 distinct phases corresponds to commensurate structures which

have been classified in three categories: AFF, AFP, and FP phases. The structures are built of ferromagnetic (001)

planes of magnetic moments oriented perpendicularly to the planes. The actual structures are realized by complex

coupling along the moment direction. Some of the planes sometimes appear frustrated and consequently the moments

within them become paramagnetic and the particular plane behaves nonmagnetically (after Rossat-Mignot et al. 1983,

1990).

737

Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction

phases characterized by a variety of long-period col-

linear magnetic structures (see Fig. 14) demonstrates

the importance of long-range exchange interactions.

Numerous examples of magnetic phase diagrams

of specific materials can be found in other articles

(see: Magnetic Phase Transitions: Field-induced (Or-

der to Order), Figs. 1–3, Metamagnetism: Itinerant

Electrons, Figs. 1 and 6) and in review papers on

magnetism in rare-earth intermetallic compounds by

Gignoux and Schmitt (1991, 1995) and uranium in-

termetallics (Sechovsky´ and Havela 1998).

5. Magnetocrystalline Anisotropy

Magnetocrystalline anisotropy is manifested by lock-

ing magnetic moments in certain crystallographic di-

rections. Anisotropy is one of the most important

characteristics of materials considered for permanent

magnet applications (see Magnetic Anisotropy and

Hard Magnetic Materials, Basic Principles of ). In par-

ticular, the anisotropy energy E

A

(or the anisotropy

field H

A

) is one of the key parameters determining the

coercive field in ferromagnets. The value of E

A

depends

on the orientation of magnetization with respect to the

crystallographic axes and therefore it can be expressed

in terms of directional cosines a

1

, a

2

,anda

3

of the

magnetization vector with respect to the main cry-

stallographic directions [100], [010], and [001], respec-

tively (for a detailed explanation see Chikazumi 1964,

Gilles 1994). For cubic crystals such as iron and nickel

the magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy is given by:

E

A

¼ K

1

ða

2

1

a

2

2

þ a

2

2

a

2

3

þ a

2

1

a

2

3

ÞþK

2

a

2

1

a

2

2

a

2

3

þ y ; ð12Þ

where K

i

is the ith anisotropy constant. For Fe,

K

1

¼4.8 10

4

Jm

3

and K

2

¼75 10

3

Jm

3

,andfor

Ni, K

1

¼4.5 10

3

Jm

3

and K

2

¼2.34 10

3

Jm

3

;in

both cases the values refer to room temperature.

For materials with tetragonal symmetry

E

A

¼ K

1

a

2

3

þ K

2

a

4

3

þ K

3

a

4

1

a

4

2

: ð13Þ

and for hexagonal crystals E

A

is usually expressed

using the description of magnetization direction by

polar angles:

E

A

¼K

u1

sin

2

y þ K

u2

sin

4

y þ K

u2

sin

6

y

þ K

3

sin

6

ycos6f; ð14Þ

where y is the angle with respect to the hexagonal

c-axis and f represents the orientation within the

basal plane. For cobalt at room temperature

K

u1

¼4.1 10

5

Jm

3

and K

u2

¼1 10

5

Jm

3

.

The easy magnetization direction is associated with

the minimum of E

A

whereas the maximum of E

A

determines the hard magnetization direction. For hex-

agonal and cubic crystals, the conditions for various

types of anisotropy are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

In localized electron systems the magnetocrystalline

anisotropy arises from the single-ion crystal-field in-

teraction between the aspherical d-orf-charge cloud

and the charge distribution surrounding the d or f ion

(crystal field) (see Crystal Field Effects in Intermetallic

Compounds: Inelastic Neutron Scattering Results). In

this context, the magnetocrystalline anisotropy is a

consequence of the directional dependence of the en-

ergy of a d-orf-charge cloud in the crystal field. The

crystallographic direction associated with the energy

minimum determines the easy magnetization direction

along which the d or f magnetic moment preferentially

orients with respect to the crystallographic axes. Shape

differences of the d-orf-electron cloud lead to differ-

ent easy magnetization directions among analogous

materials where the d or f ions experience the same

crystal field (Legvold 1980).

The involvement of delocalized 5f states in light ac-

tinide intermetallics in anisotropic covalent bonding

implies an essentially different interaction, the two-ion

(5f–5f) interaction, which plays a major role in the

magnetocrystalline anisotropy of actinide materials.

An analogous mechanism may account for the mag-

netocrystalline anisotropy in metallic 3d electron

magnets (Gignoux and Schmitt 1991). Generally, the

existence of an orbital magnetic moment and a strong

spin–orbit interaction is a necessary prerequisite for

the magnetocrystalline anisotropy mechanisms. In the

case of new observations of strong orbital magne-

tism and consequently very strong magnetocrystalline

Table 2

Summary of magnetocrystalline anisotropy parameters for cubic systems.

Easy magnetization direction [100] [010] [001]

E

A

0 1/4 K

1

1/3 K

1

þ1/27 K

1

Conditions for K

1

, K

2

K

1

40, K

1

41/9K

2

0oK

1

44/9K

2

0oK

1

o1/9K

2

Table 3

Summary of magnetocrystalline anisotropy parameters

for hexagonal systems.

Easy magnetization direction [001] Basal plane

E

A

0 K

u1

þK

u2

Conditions for K

u1

, K

u2

K

u1

þK

u2

0 K

u1

þK

u2

o0

738

Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction

anisotropy in itinerant electron systems the sophisti-

cated electronic structure calculations (Brooks and

Johanson 1993) played a principal role.

6. Basic Models of Magnetism

For the interpretation of magnetic phenomena rele-

vant microscopic models are frequently used. The

basic three models are discussed in this section.

Equation (9) defines the Heisenberg Hamiltonian

of the isotropic exchange interaction between two

S-state ions (characterized by spin angular momen-

tum S) that is the basis of the Heisenberg model. This

model is most applicable to materials where the iso-

tropic exchange interaction dominates the crystal-

field interaction and there are possible anisotropic

exchange interactions.

At the same time, together with the Ising model, it

has been one of the standard models for cooperative

phenomena and phase transitions. The Ising model is

described by the Hamiltonian

H

ij

¼2J

ij

#m

i

#m

j

ð15Þ

where m

i

is a variable with a value of þ1or1. This

Hamiltonian can be regarded as a limiting case of

Eqn. (9) in which S is assumed to be 1/2 and the

exchange coefficient of the transverse component

S

ix

S

jx

þS

iy

S

jy

is negligible. The model is useful for

systems where strong uniaxial anisotropy locks the

magnetic moments along one crystallographic axis

(usually the z-axis). On the other hand, the opposite

limit of dominating transverse components leads to

the XY model expressed by the Hamiltonian

H

ij

¼2J

ij

ð

#

S

ix

#

S

jx

þ

#

S

iy

#

S

jy

Þð16Þ

A possible application of the XY model can be found

in materials with strong easy-plane anisotropy.

See also: Alloys of 4f (R) and 3d (T) Elements:

Magnetism; Magnetic Excitations in Solids

Bibliography

Ashcroft N W, Mermin N D 1988 Solid State Physics. Saunders

College Publishing, New York Chap. 31–3

Bacon G E 1975 Neutron Diffraction. Oxford University Press,

Oxford

Barbara B, Gignoux D, Vettier C 1988 Lectures on Modern

Magnetism. Springer, Berlin

Boring A M, Smith J L 2000 Plutonium condensed-matter

physics: a survey of theory and experiment. Los Alamos Sci.

26, 42–80

Brooks M S S, Johanson B 1993 Density functional theory of

the ground state magnetic properties of rare earths and ac-

tinides. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Handbook of Magnetic

Materials. North Holland, Amsterdam, pp. 139–230 Vol. 7

Buschow K H J, Wohlfarth E P (eds.) 1993 Handbook of Mag-

netic Materials. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Cahn R W, Lifshin E 1993 Concise Encyclopedia of Materials

Characterization. Pergamon, Oxford

Chikazumi S 1964 Physics of Magnetism. Wiley, New York

Cracknel A P 1975 Magnetism in Crystalline Solids. Pergamon

Press, Oxford

Eriksson O, Nordstrom L, Brooks M S S, Johansson B 1988 4f-

band magnetism in CeFe

2

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 2523–6

Fisher M E 1962 Relation between the specific heat and sus-

ceptibility of an antiferromagnet. Phil. Mag. 7, 1731

Gignoux D, Schmitt D 1991 Rare earth intermetallics. J. Magn.

Magn. Mater. 100, 99–125

Gignoux D, Schmitt D 1995 Metamagnetism and complex

magnetic phase diagram of rare earth intermetallics. J. Alloys

Compds. 225, 423–31

Gilles J 1994 Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. Chapman &

Hall, London

Hurd M 1983 Varieties of magnetic order in solids. Contemp.

Phys. 23, 469–98

Jensen J, Mackintosh A R 1991 Rare Earth Magnetism. Claren-

don Press, Oxford

Kittel C 1976 Introduction to Solid State Physics. Wiley, New

York

Kubo K, Ohata N 1972 A quantum theory of double exchange.

J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 33, 21–32

Legvold S 1980 Rare earth metals and alloys. In: Wohlfarth E P

(ed.) Ferromagnetic Materials. North Holland, Amsterdam,

pp. 184–295

Mattis D C 1981 The Theory of Magnetism I. Springer, Berlin

Rossat-Mignod J 1987 Magnetic structures. In: Sko

¨

ld K, Price

D L (eds.) Methods of Experimental Physics. Academic Press,

New York, Vol. 23, part C, pp. 69

Rossat-Mignod J, Burlet P, Quezel S, Effantin J M, Delaconte

D, Bartholin H, Vogt O, Ravot D 1983 Magnetic properties

of cerium monopnictides. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 31–4,

398–404

Rossat-Mignod J, Burlet P, Regnault L P, Vettier C 1990

Neutron scattering and magnetic phase transitions. J. Magn.

Magn. Mater. 90–1, 5–16

Sandratskii L M 1998 Noncollinear magnetism in itinerant-

electron systems: theory and applications. Adv. Phys. 47,

91–160

Schenck A, Gygax F N 1995 Magnetic materials studied by

muon spin rotation spectroscopy. In: Buschow K H J (ed.)

Handbook of Magnetic Materials. North Holland, Amster-

dam, Vol. 9, pp. 57–302

Sechovsky´ V, Havela L 1998 Magnetism of ternary intermetal-

lic compounds of uranium. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Hand-

book of Magnetic Materials. North Holland, Amsterdam,

Vol. 11, pp. 1–289

Smith J L, Bohring A M 2000 Plutonium condensed-matter

physics. A survey of theory and experiment. Los Alamos Sci.

26, 90–127

Smith J L, Kmetko E A 1983 Magnetism or bonding: a nearly

Periodic Table of transition elements. J. Less Common Met-

als 90, 83–91

Squires G L 1978 Introduction to the Theory of Thermal Neutron

Scattering. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Yosida K 1996 Theory of Magnetism. Springer, Berlin

V. Sechovsky´

Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic

739

Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction