Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Zhu J-G 1989 Interactive phenomena in magnetic thin films.

Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California at San Diego,

pp. 24–35

Zhu J-G 2001 Micromagnetic modeling of domain structures in

magnetic thin films. In: De Graef M, Zhu Y (eds.) Magnetic

Imaging and Its Applications to Materials. Academic Press,

pp. 1–26

Zhu J-G, Zheng Y 2002 The micromagnetics of magnetoresis-

tive random access memory. In: Hillebrands B, Ounadjela K

(eds.) Spin Dynamics in Confined Magnetic Structures I.

Springer, pp. 89–325

J.-G. Zhu

Dept of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Carnegie

Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3890, USA

Magnetocaloric Effect: From Theory

to Practice

It is known that as an external magnetic field is ap-

plied to a magnet under adiabatic conditions (i.e.,

under the conditions of constant total entropy of the

body, S ¼constant), the initial temperature T of the

body may vary due to the magnetocaloric effect

(MCE) by the value DT. It can result in an increase or

in a reduction of the original temperature of a mag-

netic material. This is a consequence of the variation,

under the field, of the internal energy under the in-

fluence of an external field of the material possessing

a magnetic structure. In 1881 Warburg first discov-

ered MCE as a heat evolution in iron under a mag-

netic field. In principle, the term MCE should be

considered more widely as a description of the pro-

cesses of entropy variation of the magnetic subsystem.

MCE investigations were shown to yield the kind of

information that can hardly be obtained by other

techniques. In recent years the interest in investiga-

tions of the MCE and the influence of the magnetic

field on the entropy has become renewed due to the

possibility to obtain information on magnetic phase

transitions and the prospects of using some of these

materials in magnetic refrigerators (Tishin 1999). The

thermodynamic approach is most elaborate for the

understanding of the observed phenomena. Also often

used are Landau’s theory of second-order phase tran-

sitions and the mean-field approximation (MFA).

In general, the heat generation and absorption in

magnetic materials during adiabatic processes include

not only MCE but also elastocaloric effects (ECE).

The ECE is a heat emission or absorption at a con-

stant applied magnetic field (in a simple case at zero

field) and changing external pressure. If a pressure

change takes place under adiabatic conditions then

the ECE (like MCE) manifests itself as heating or

cooling of a magnet.

1. Elements of Thermodynamic Theory

Considering the total entropy of the system, S(T, H,

p), the total differential can be written as:

dS ¼ð@S=@T Þ

H;p

dT þð@S=@HÞ

T;p

dH

þð@S=@pÞ

T;H

dp ð1Þ

where p is the pressure, H is the magnetic field.

For an adiabatic-isobaric process (dp ¼0) one can

obtain from Eqn. (1) with Maxwell’s relations the

following expression for the temperature change due

to the change of the magnetic field (the MCE):

dT ¼ðT=C

H;p

Þð@M=@TÞ

H;p

dH ð2Þ

where C

H,p

denotes the specific heat at constant field

and pressure (see Magnetic Systems: Specific Heat).

The thermodynamic equations obtained above are

sufficiently general, since no assumptions as to the

structure of the considered system were made. To

obtain more concrete results one should know the

form of the functions of the free energy of a specific

system, which requires some model assumptions. It is

known that in ferromagnets normally a second-order

phase transition takes place at the Curie point, T

C

.

Belov (1961) adopted the Landau theory of second-

order phase transitions to magnetic transitions. Ac-

cording to this theory, the values of the MCE of a

ferromagnet which is brought into a magnetic field,

H, near the Curie temperature as well as an expres-

sion describing the MCE field dependence near the

Curie temperature can be calculated.

Above we have considered the MCE in relation to

a reversible process of magnetization. Nonreversible

magnetothermal effects can arise due to such proc-

esses of magnetization as displacement of domain

walls and nonreversible rotation of the saturation

magnetization, first-order magnetic phase transitions,

and Foucalt currents. The nonreversible effects can

decrease the sample cooling under adiabatic demag-

netization.

The constancy of the total entropy in studies of

MCE means (in the case when the total entropy of the

magnet can be represented as the sum of three parts:

S

L

, S

M,

S

E

—the lattice, magnetic, and electronic en-

tropy, respectively), that as the field is increased from

zero up to H it is possible to write:

S

L

ðTÞþS

M

ð0; TÞþS

E

ðTÞ

¼ S

L

ðT þ dT

1

ÞþS

M

ðH

1

; T þ dT

1

Þ

þ S

E

ðT þ dT

1

Þ¼y ¼ S

L

ðT

i1

þ dT

i

Þ

þ S

M

ðH

i

; T

i1

þ dT

i

ÞþS

E

ðT

i1

þ dT

i

Þ¼y

¼ S

L

ðT þ DTÞþS

M

ðH; T þDTÞþS

E

ðT þ DTÞð3Þ

where dT

i

is the infinitesimal gain in the MCE

value as the field increases from H

i1

up to H

i

,

760

Magnetocaloric Effect: From Theory to Practice

T

i

¼dT

i

þT

i1

. If the value of S

E

(T) has a small

change then the Eqn. (3) can be rewritten as:

DS

M

ðH; TÞ¼ðS

M

ðH; T þDTÞS

M

ð0; TÞÞ

¼S

L

ðT þ DTÞS

L

ðTÞ¼DS

L

ðTÞð4Þ

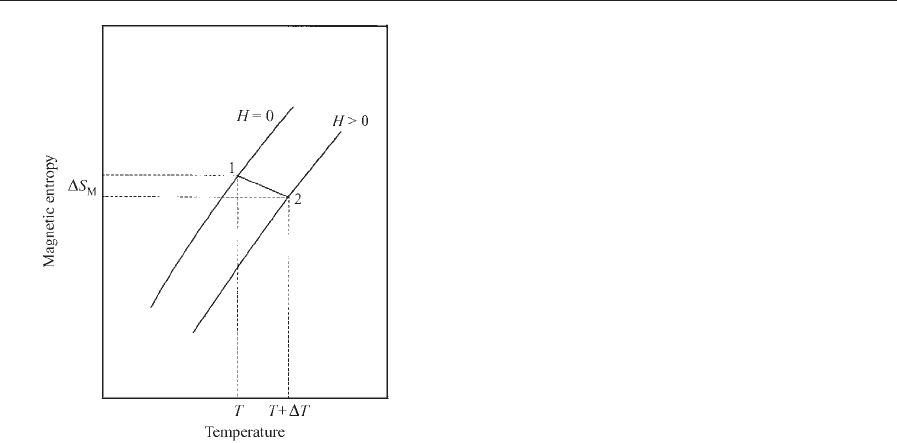

Thus, as the magnetic entropy is changed by the

value DS

M

(H, T) (in this case the value of S

M

is de-

creased from point 1 to 2 as shown in Fig. 1) the

lattice entropy is decreased by the same amount but

with the opposite sign. It should be noted that, as one

can see from Eqn. (3), as the field changes, the sum of

entropies of the magnetic and lattice subsystems re-

mains constant (at each particular moment of time).

At the same time, it seems that the specific part of

each contribution to the total entropy of the magnet

may vary. In simple one-domain isotropic collinear

magnetic structures the field effect is known to result

in a stricter alignment of the atomic magnetic mo-

ments in the magnetic field direction. Thus, a de-

crease in magnetic entropy as the field increases (the

positive MCE) is usually associated with an increas-

ing order of the magnetic subsystem.

The maximum possible variations in the magnetic

entropy for one mole of free ions, as predicted by the

theory, is DS

max

¼R ln(2J þ1), where R is the uni-

versal gas constant and J is the total angular moment.

From the classic point of view, the change of S

M

is

usually related to the rotation of the magnetic mo-

ment vectors under influence of the magnetic field

(i.e., the S

M

decreases with increasing magnetization

in classic magnetic materials). In reality, the magnetic

entropy (and consequently the sample temperature)

continues to change even in the high field region, just

because the probability of atomic magnetic moment

deflection from the field direction (due to the thermal

fluctuations) remains nonzero even in high magnetic

fields.

The magnitude of the isothermal magnetic entropy

change, DS

M

, as well as the total entropy change, DS,

with the change of magnetic field DH ¼H

2

H

1

can

be calculated from the Maxwell relation on the basis

of magnetization data as:

DS

M

¼

Z

H

2

H

1

ð@MðH; TÞ=@TÞ

H

dH ð5Þ

The magnetic entropy S

M

(H, T) can be also calcu-

lated as:

S

M

¼

Z

T

0

ðC

M

ðH; TÞ=TÞdT ð6Þ

where C

M

(H, T) is the magnetic heat capacity.

2. Methods of MCE Measurements

At present, there are two main practical methods for

the determination of the DT value. The first method

involves direct measurement of the temperature

change DT( H, T) ¼T

f

T (where T

f

is the final tem-

perature) of the sample placed in adiabatic conditions

under the influence of an external field. The second

way is indirect and based on the calculation of the

MCE value on the basis of experimental data on the

heat capacity and/or magnetization.

The method of direct measurements of the change

in material temperature during the application or re-

moval of a magnetic field by an electromagnet

(switch-on technique) has been used for MCE exper-

iments since the 1930s. When the field is produced by

an electromagnet the rise time has a maximum value

of about a few seconds, while it can be several min-

utes for a superconducting solenoid. During the field

rise a dissipation of heat produced in the sample by

the MCE can occur. Estimations show that the field

rising time must not be greater than 10 seconds for

temperatures above 30 K. This implies that MCE

measurements made by a switch-on technique are

difficult when using a superconducting solenoid.

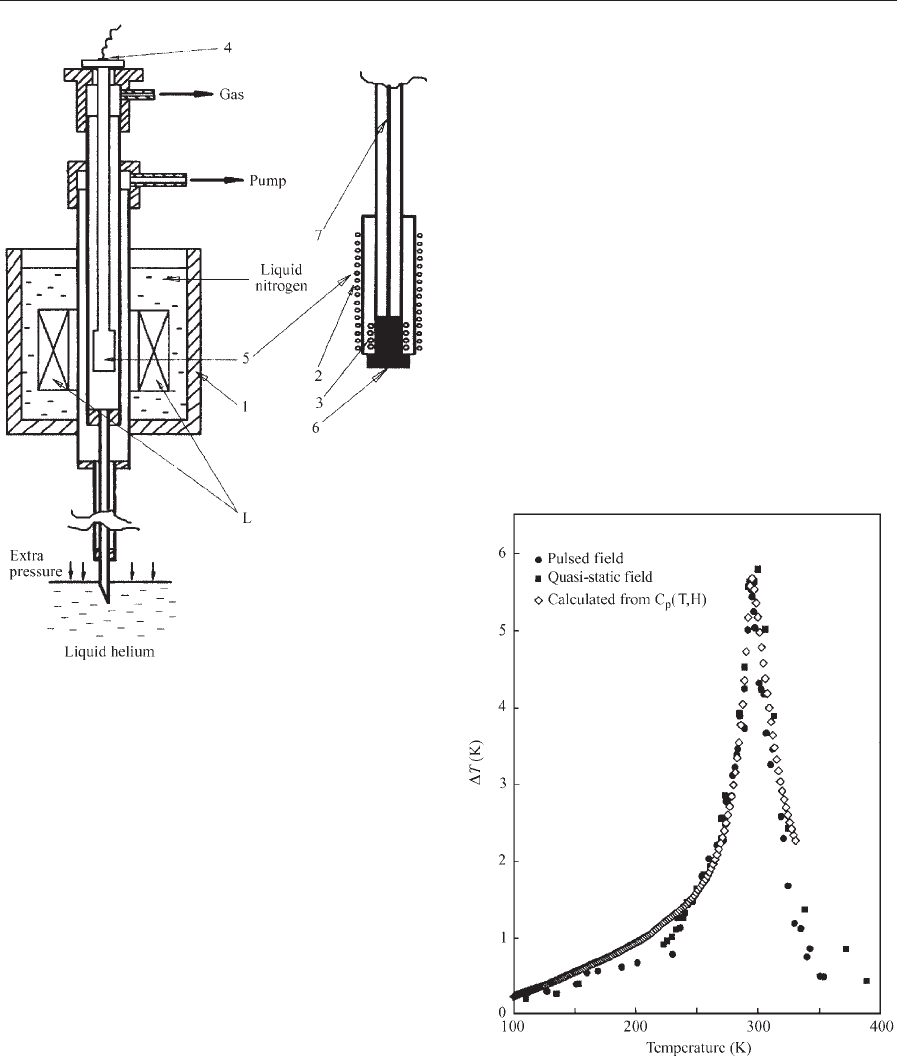

Consider as an example the pulsed field setup, as

described by Dan’kov et al. (1997). The principal

scheme of this setup is shown in Fig. 2. Changes of

the sample temperature were measured by a copper-

constantan thermocouple made of small diameter

wires (B0.05 mm). This provides a small mass of

thermocouple (typical weight of the sample is about

1 g) and, consequently, a negligible heat load, which

significantly reduces the heat that leaks through the

electrical wires. The gadolinium sample, measured by

Figure 1

The example of the magnetic entropy curves without

magnetic field and at magnetic field H ¼constant.

761

Magnetocaloric Effect: From Theory to Practice

Dan’kov et al. (1997) was shaped as a parallelepiped

with the dimensions 4 4 10 mm and cut into two

equal parts along the long axes. The thermocouple

was placed between the parts in the center of the

sample. The magnetic field was created by the sole-

noid L under the discharge of a battery of capacitors

C. This technique made it possible to determine the

sample temperature change due to the change of the

magnetic field, i.e., the MCE at a given field and

temperature.

Experimental data on the magnetic field depend-

ence of the magnetization at constant temperatures

allows calculation of the magnetic entropy change by

means of Eqn. (5) and the MCE by Eqn. (2).

Another method for the evaluation of DS

M

is based

on the fact that the temperature dependence of the

total entropy in the presence of a magnetic field

S(H, T) is shifted on the temperature axis relative to

the zero-field total entropy S(0, T)tohighertemper-

atures by the value of MCE for a magnetic material

under adiabatic conditions. This method is based on

the heat capacity measurements and has been pro-

posed by Brown (1976). It allows determination of all

parameters required for magnetic refrigeration design.

3. MCE in Different Magnetic Materials

The heavy rare-earth metals (REM) gadolinium to

lutetium (except ytterbium) and yttrium have hexa-

gonal close-packed (h.c.p.) crystalline structures. In

the magnetically ordered state they display complex

magnetic structures (except gadolinium) (see Alloys of

4f (R) and 3d Elements (T): Magnetism, Localized 4f

and 5f Moments: Magnetism). The MCE and heat

capacity of single crystal and polycrystalline samples

of heavy REMs have been studied by many authors.

The temperature dependence of the MCE of gado-

linium obtained by various experimental methods is

presented in Fig. 3. A negative MCE is characteristic

Figure 2

Low temperature part of the experimental pulsed-field

setup: (1) liquid nitrogen cryostat, (2) sample heater, (3)

field measuring coil, (4) vacuum tight feed through

connector, (5) sample holder, (6) sample inside the

holder, (7) electrical wiring, and L pulsed solenoid (after

Dan’kov et al. 1997).

Figure 3

The MCE temperature dependencies of high purity

polycrystalline Gd measured directly by quasi-static and

pulsed techniques (closed symbols) compared with those

determined from the heat capacity (open symbols) for

DH ¼20 kOe (after Dan’kov et al. 1997).

762

Magnetocaloric Effect: From Theory to Practice

of antiferromagnets (e.g., terbium and dysprosium in

low magnetic fields), in which the external field re-

duces the magnetic order rather than enhances it,

thus increasing the magnetic entropy.

MCE studies of iron, cobalt, and nickel in fields up

to 30 kOe have shown that the magnitude of the

MCE near T

C

is well described by Eqn. (2). Unlike

REMs, in 3d ferromagnets in the same field the max-

imum of the MCE is fairly sharp. The MCE in iron

and cobalt exceeds that of nickel by several fold.

MCE at the first-order transitions (e.g., from ferri-

(FI) or ferromagnetism to antiferromagnetism

(AFM)) has also been widely studied. Magnetic fields

can induce a transition from an AFM structure

present below the transition point, to a ferromagnetic

one. This is accompanied by sample cooling. In high

magnetic field, at the transition from a helicoidal an-

tiferromagnetic state to the ferromagnetic state a

positive MCE is observed.

The MCE and magnetic entropy change induced

by a magnetic field in thin films prepared on the basis

of 3d elements was also measured. MCE is due to the

uniform rotation of the spontaneous magnetization.

Experimental MCE measurements were made on po-

lycrystalline ferromagnet and single crystalline ferri-

magnetic dielectric films.

Investigation of some of oxides showed that the

MCE suddenly changes its sign in the low tempera-

ture region. An analogous behavior was observed in

rare-earth garnets. Such a behavior is related with

changes of the ferrimagnetic structure of the rare-

earth iron garnets.

The magnetothermal properties of gadolinium gal-

lium garnet (GGG), dysprosium gallium garnet

(DGG), and dysprosium aluminum garnet (DAG)

were also studied. GGG and DGG have antiferro-

magnetic ordering below T

N

¼0.8 K and 0.373 K,

respectively. Above T

N

they display simple paramag-

netic behavior. Rare-earth orthoaluminates (REOA),

RAlO

3

, have an orthorhombically distorted perovs-

kite structure. The magnetic entropy change DS

M

in-

duced by a field in GdAlO

3

, ErAlO

3

, and DyAlO

3

was calculated by Kuz’min and Tishin (1991) in the

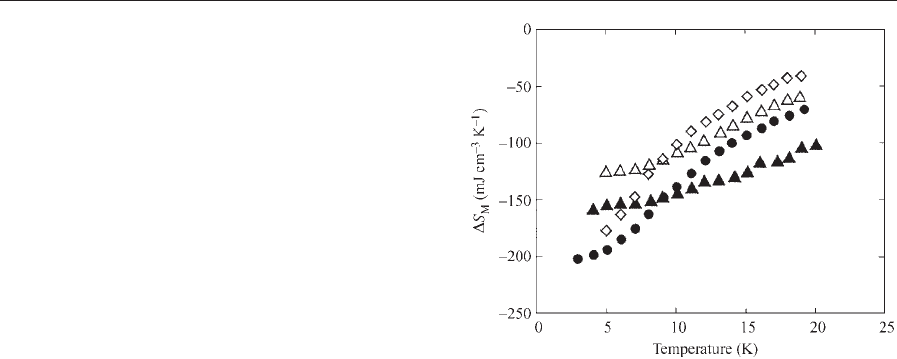

framework of MFA. Kimura et al. (1997) determined

experimental values of DS

M

for RAlO

3

on the basis

of magnetization measurements (see Fig. 4). The ex-

perimental results for DyAlO

3

and ErAlO

3

along the

easy axes are in good agreement with the previous

calculations. This supports the conclusion that

DyAlO

3

and ErAlO

3

are promising materials for

magnetic refrigeration below 20 K as proposed by

Kuz’min and Tishin (1991) on the basis of theoretical

calculations.

Modern experimental investigations in high mag-

netic fields of 5MOe and higher are nowadays noth-

ing extraordinary—the MCE value in such fields can

be extremely high. Therefore, the possibility of its

influence on the obtained experimental results needs

to be accounted for. A computer simulation analysis

of the MCE was developed for calculating peak val-

ues of the MCE in rare-earth magnets using a mean-

field approximation. The study concentrated on the

variation of the key thermodynamic parameters such

as magnetic field, temperature, and Curie and Debye

temperatures of the magnetic materials in a wide

range of values. The results of the numerical simu-

lation agree quite well with the experimental data for

the heavy lanthanides only for large magnetic fields.

The calculations reveal the fact that if the temper-

ature is high (near 1000 K), saturation of the MCE

and magnetic entropy is absent even in the highest

magnetic fields (up to 40 MOe), while near the tem-

perature of the phase transition to the paramagnetic

state the value of the magnetic entropy saturates in a

field of about 10 MOe. The analysis shows that the

DT

max

value in the vicinity of the transition point in

the series of heavy REMs is directly proportional to

the product g

J

JT

ord

and can reach, for example,

254 K in the case of terbium. For more details see

Tishin (1999).

4. Magnetic Refrigeration

The MCE is utilized in magnetic refrigeration ma-

chines. At the beginning of the century Langevin

(1905) demonstrated that changes in the paramagnet

magnetization generally resulted in a reversible tem-

perature change. The first experiments to put this

idea into practice were carried out in 1933–1934. In-

vestigations in the wide temperature region (from

Figure 4

Comparison of DS

M

temperature dependencies in

DyAlO

3

(closed triangles) measured along b-axis and in

ErAlO

3

(closed circles) along c-axis with that in

Gd

3

Ga

5

O

12

(open diamonds) and Dy

3

Al

5

O

12

(open

triangles) measured along [111] direction with a

magnetic field change of 50 kOe (after Kimura et al.

1997).

763

Magnetocaloric Effect: From Theory to Practice

4.2 K to room temperature and even higher) were

started by Brown (1976). Technologically, the current

interest in the MCE is connected with the real pos-

sibility to employ materials with large MCE values in

the phase transition in magnetic refrigerators. The

current extensive interest aims to demonstrate that

magnetic refrigeration is one of most efficient method

of cooling at room temperatures and higher. For in-

stance, the Ames Laboratory (Iowa State University,

USA) and the Astronautics Corporation of America

have been collaborating and developing an advanced

industrial prototype of such a magnetic refrigerator

(Zimm et al. 1998). In principle, these refrigerators

could be used in hydrogen liquefiers, large building

air conditioning, vehicle passenger coolers, IR detec-

tors, high-speed computers, and SQUIDs.

At present only REM materials are recognized as

appropriate for these purposes. According to Barclay

(1994), the REM materials can be used in gas cycle

refrigerators as passive regenerators. In magnetic re-

frigerators they can be applied as working materials

(bodies) in externally regenerated or nonregenerative

cycles. They can also serve as active magnetic regen-

erative refrigerators (AMRR).

A regenerator serves to expand a refrigerator tem-

perature span, since the temperature span produced

by the adiabatic process itself is insufficient to achieve

the desired temperature (especially in the case of

magnetic materials). With the help of a regenerator

the heat is absorbed from, or returned to, the work-

ing material at the various stages of a regenerative

thermodynamical cycle.

In the low-temperature region the heat capacity of

conventional regenerators in cryogenic refrigerators

essentially decreases, since the lattice heat capacity of

a solid is proportional to T

3

and the electronic heat

capacity in metals is proportional to T. In the refrig-

erators used for cooling helium gas this leads to a

rapid decrease of the refrigerator effectiveness be-

cause below about 10 K the volume heat capacity of

compressed helium increases. Buschow et al. (1975)

proposed rare-earth compounds as a possible solu-

tion of this problem. The statement was based on the

fact that in rare-earth compounds the low magnetic

ordering temperatures and the associated heat ca-

pacity peaks offer relatively high magnetic contribu-

tions to the volume heat capacity. Practical

constructions of passive magnetic regenerators using

Er

3

Ni appeared after investigations of the heat ca-

pacity of various R–Ni compounds made by Hashi-

moto and co-workers (1986). The use of passive

magnetic regenerators allowed it to reach 4.2 K and

to increase the cooling power.

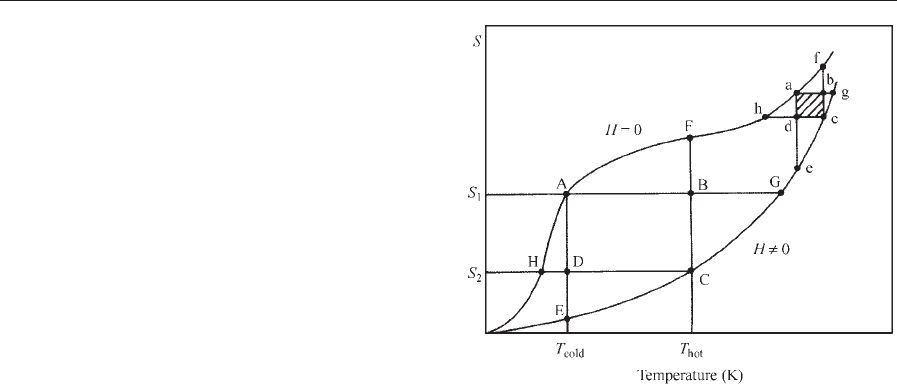

In magnetic refrigerators a nonregenerative Carnot

cycle is used in conjunction with magnetic type re-

generative Brayton and Ericsson cycles and with ac-

tive magnetic regenerator (AMR) cycles (Barclay

1994). A Carnot cycle with a temperature span from

T

cold

to T

hot

is shown by the rectangle ABCD in the

total entropy—temperature (S–T) diagram in Fig. 5.

The heat Q, corresponding to the load during one

cycle of refrigeration is equal to T

cold

DS

M

. Increasing

the temperature span beyond a certain optimal value

leads to a significant loss of efficiency as point C in

Fig. 5 tends to approach point G and the cycle area

becomes narrow. The temperature span of the Carnot

cycle for a given T

cold

and H is limited by the distance

AG (i.e., by the MCE at T ¼T

cold

and the field

change from 0 to H), when Q becomes zero. At tem-

peratures above 20 K the lattice entropy of solids

strongly increases, which leads to a decrease of the

Carnot cycle area (see rectangle ABCD in Fig. 5).

That is why applications of Carnot-type refrigerators

are restricted to temperatures region below 20 K.

Magnetic refrigerators operating at higher temper-

atures have to employ other thermodynamic cycles,

including processes at constant magnetic field. Such

cycles, as distinct from the Carnot cycle, allow the use

of the area between the curves H ¼0 and Ha0 in the

S–T diagram more fully. The rectangles AFCE and

AGCH present the Ericsson and Brayton cycles, re-

spectively. The two cycles differ in the way the field

change is accomplished, isothermally in the Ericsson

cycle and adiabatically in the Brayton cycle. Reali-

zation of isofield processes in both of these cycles

requires heat regeneration.

The first room temperature magnetic refrigerator

using a regenerative magnetic Ericsson cycle is the

device proposed by Brown (1976). The regenerator

consists of a vertical column with fluid (0.4 m

3

, 80%

water and 20% alcohol). The magnetic working ma-

terial immersed in the regenerator consists of 1 mol of

Figure 5

S–T diagram of thermodynamic cycles used for

magnetic refrigeration. Two isofield curves are shown:

for H ¼0 and H40 (after Kuz’min and Tishin 1991).

764

Magnetocaloric Effect: From Theory to Practice

1 mm thick Gd plates, separated by screen wire to

allow the regeneration fluid to pass through in the

vertical direction. The working material is held sta-

tionary in a magnet while the tube containing the

fluid oscillates up and down. If initially the regener-

ator fluid is at room temperature, after about 50 cy-

cles the temperature at the top can reach þ46 1C and

the temperature at the bottom can reach 1 1C. The

temperature gradient in this device is maintained in

the regenerator column.

In the AMR refrigerator the magnetic working

material and regenerator are joint in one unit. In this

case the temperature gradient exists inside the work-

ing material and such a cycle cannot be described by

a conventional gas cycle analogue. Consider the

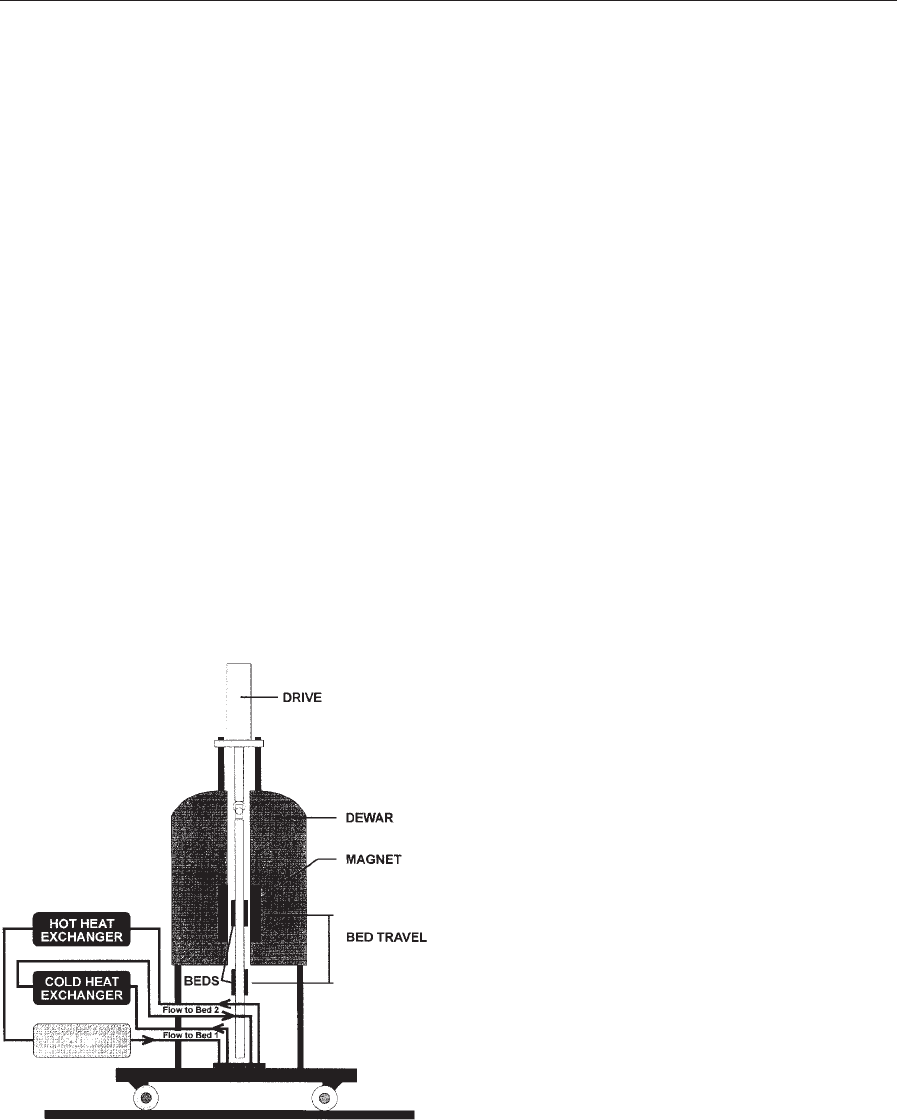

AMRR construction proposed by Zimm et al. (1998),

which is shown in Fig. 6. A magnetic field up to

50 kOe is provided by a helium cooled superconduct-

ing solenoid working in the persistent mode. Two

beds, each composed of 1.5 kg of gadolinium spheres,

are used as the AMR. The spheres have a diameter of

150–300 mm and are made by a plasma-rotating elec-

trode process. The beds are, by turns, moved in and

out of the Dewar bore with a magnetic field. Water is

used as a heat transfer fluid. The working cycle of the

device started with water cooling by blowing it

through the demagnetized bed located inside the

magnetic area (bottom position in Fig. 6).

Then the water passes through the cold heat ex-

changer picking up the thermal load from the cooling

object. After this the water is blown through the

magnetized bed located in the magnetic field area

where it absorbs the heat evolved due to the MCE.

Next the water passes through the hot heat exchang-

er, releasing the heat absorbed from the magnetized

bed. The cycle is finished by removing the magnetized

bed from the magnet and replacing it by the demag-

netized one. Such a device, working at 0.17 Hz with a

field of 50 kOe in the room temperature range with a

temperature span of 5 K, provides a cooling power of

600 W (which is about 100 times better than in pre-

vious constructions) with a maximum efficiency of 60

% that of a Carnot process.

The suggestion to use binary and more complicat-

ed rare-earth alloys as working bodies for the room

temperature region was made by Tishin in 1990. For

the application in an ideal Ericsson magnetic regen-

erator cycle a magnetic working material should have

a magnetic entropy change DS

M

that is constant in

the cycle temperature span. The use of terbium–

gadolinium and dysprosium–gadolinium alloys as

magnetic refrigerators near room temperature is

more effective than the use of pure gadolinium.

Hashimoto et al. (1986) proposed for a magnetic

Ericsson cycle with a temperature span from 10 K to

80 K the use of complex magnetic materials consist-

ing of RAl

2

intermetallic compounds (R ¼heavy

REM). Pecharsky and Gschneidner (1997) proposed

the use of the unique behavior of the alloys

Gd

5

(Si

x

Ge

1x

)

4

to improve the efficiencies of the

magnetic refrigerators.

As mentioned above, refrigerators without regen-

eration and working with a Carnot cycle can be used

below 20 K. Among various oxide compounds

Gd

2

Ga

5

O

12

, DyAlO

3

, and ErAlO

3

are the most suit-

able working materials for magnetic refrigerators in

the temperature range between 2 K and 20 K.

Thus, we have considered the passive and active

magnetic refrigerators and materials that can be used

for their operation. In conclusion, it is evident that

magnetic cooling is a promising technology for the

refrigeration industry and may become an important

market for the rare-earth industry in the future.

See also: Demagnetization: Nuclear and Adiabatic;

Magnetic Refrigeration at Room Temperature

Bibliography

Barclay J A 1994 Active and passive magnetic regenerator in

gas/magnetic refrigerators. J. Alloys Comp. 207/208, 355–61

Belov K P 1961 Magnetic Transformations. Consultant Bureau,

New York

Brown G V 1976 Magnetic heat pumping near room temper-

ature. J. Appl. Phys. 47, 3673–80

Buschow K H J, Olijhoek J F, Miedema A R 1975 Extremely

large heat capacity between 4 and 10 K. Cryogenics 15, 261

Dankov S Y, Tishin A M, Pecharsky V K, Gschneidner K A Jr.

1997 Experimental device for studying the magnetocaloric

Figure 6

Construction of an AMR refrigerator operating at near

room temperature (after Zimm et al. 1998).

765

Magnetocaloric Effect: From Theory to Practice

effect in pulse magnetic fields. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 68,

2432–7

Hashimoto T 1986 Recent investigations of refrigerant for

magnetic refrigerators. Adv. Cryog. Eng. Mater. 32, 261–78

Kimura H, Numazawa T, Sato M, Ikeya T, Fukuda T, Fujioka

K 1997 Single crystals of RAlO

3

(R: Dy, Ho and Er) for use

in magnetic refrigeration between 4.2 and 20 K. J. Mater. Sci.

32, 5743–7

Kuz’min M D, Tishin A M 1991 Magnetic refrigerants for the

4.2–20 K Region: Garnets or Perovskites? J. Phys. D 24,

2039–44

Langevin M P 1905 Magnetisme et theorie des electrons. Ann.

Chim. Phys. 5, 70–113

Pecharsky V K, Gschneidner K A Jr. 1997 Giant magneto-

caloric effect in Gd

5

(Si

2

Ge

2

). Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 4494

Tishin A M 1999 Magnetocaloric effect in the vicinity of phase

transitions. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Handbook of Magnetic

Materials. North-Holland, Amsterdam, Vol. 12, Chap. 4,

pp. 395–524

Warburg E 1881 Magnetische untersuchungen. I. Uber einige

wirkungen der coercitivkraft. Ann. Phys. 13, 141–64

Zimm C, Jastrab A, Sternberg A, Pecharsky V, Gschneidner K

Jr., Osborn M, Anderson I 1998 Description and perform-

ance of a near-room temperature magnetic refrigerator. Adv.

Cryog. Eng. 43, 1759

A. M. Tishin

M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia

Magnetoelastic Phenomena

Magnetoelasticity is a mutual influence of the mag-

netic and the elastic properties of materials. It orig-

inates from the fact that all main interactions

between the atomic magnetic moments in solids de-

pend on the distance between them (e.g., exchange

interaction, dipole–dipole interaction, interaction of

magnetic moments with crystal electric field). The di-

mensions, shape, and elastic properties of a sample

are influenced by its magnetic state. This is the direct

magnetoelastic effect or the magnetostriction (MS).

The magnetic properties (magnetization, magnetic

ordering temperature, magnetic anisotropy energy)

are influenced by the applied and internal mechanical

stresses (inverse magnetoelastic effects).

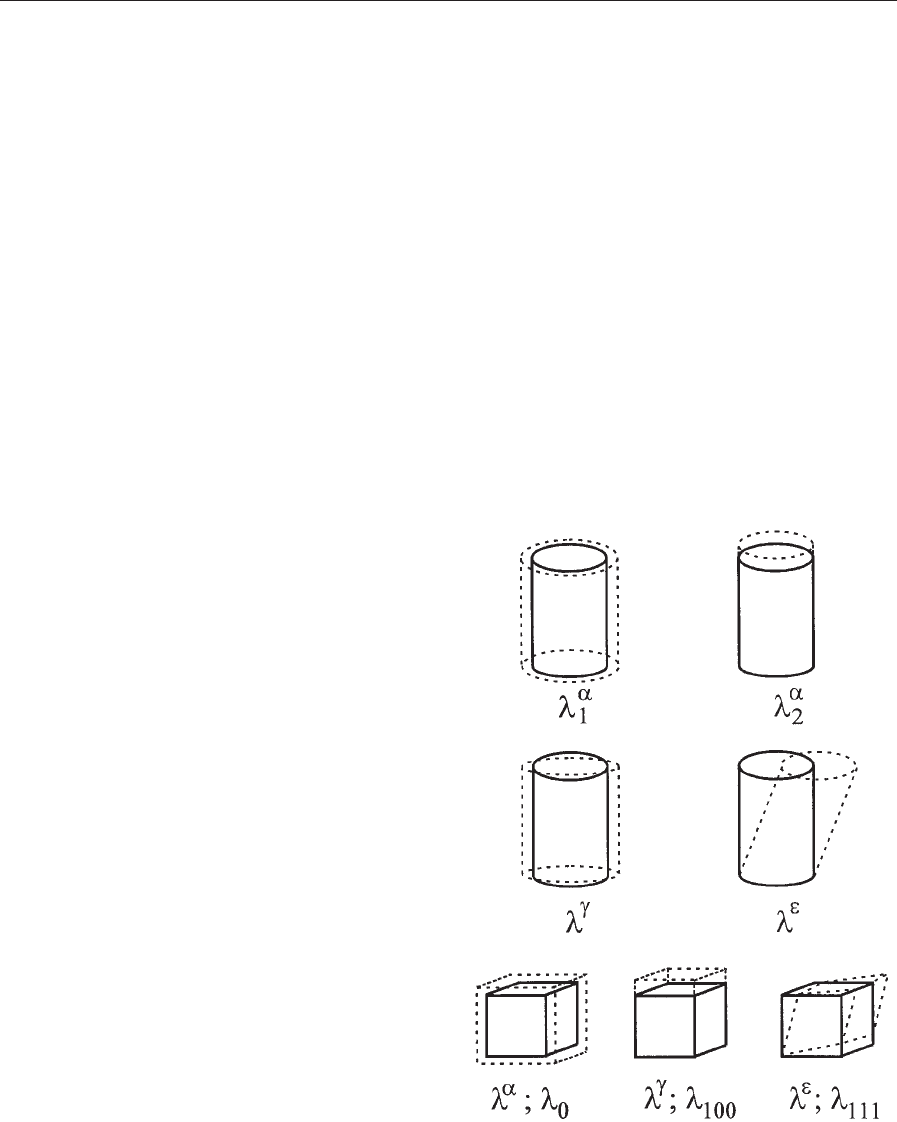

The dependence of a magnetostrictive strain, l,on

the direction of its measurement and the orientation

of the magnetization vector (M) in a crystal is des-

cribed by phenomenological formulas specific to a

certain crystal symmetry (Clark 1980, Belov et al.

1983). For a hexagonal crystal, e.g., cobalt, rare earth

(R) metals, and many intermetallic compounds:

l ¼l

a;0

1

ðb

2

x

þ b

2

y

Þþl

a;0

2

b

2

z

þ l

a;2

1

ðb

2

x

þ b

2

y

Þða

2

z

1=3Þ

þ l

a;2

2

b

2

z

ða

2

z

1=3Þþl

g;2

½0:5ðb

2

x

b

2

y

Þða

2

x

a

2

y

Þ

þ 2a

x

b

x

a

y

b

y

þ2l

e;2

ða

x

b

x

þ a

y

b

y

Þa

z

b

z

ð1Þ

where a

i

are the cosines of the magnetization direc-

tion, b

i

are the cosines of the strain measurement di-

rection, and l

i

are the MS constants. The constants

with index a describe the changes in interatomic dis-

tances within the basal plane (l

a

1

) and along the c-axis

(l

a

2

) and do not reduce the lattice symmetry. As seen

from Eqn. (1), the terms with zero-order constants,

l

a;0

i

, do not depend on the magnetization direction

and describe the isotropic part of this type of MS,

while the terms with second-order constants, l

a;2

i

,

correspond to the anisotropic part. A reduction of

symmetry is described by the constants with index g

(an orthorhombic distortion in the basal plane) and e

(a deviation from the orthogonality between the basal

plane and the c-axis). The MS which reduces the

symmetry is essentially anisotropic. The MS modes

for hexagonal and cubic crystals are shown in Fig. 1.

For a cubic crystal (e.g., iron and nickel and their

alloys, ferrites, RFe

2

):

l ¼l

a;0

þ l

g;2

ða

2

x

b

2

x

þ a

2

y

a

2

y

b

2

y

þ a

2

z

b

2

z

1=3Þ

þ 2l

e;2

ða

x

a

y

b

x

b

y

þ a

y

a

z

b

y

b

z

þ a

x

a

z

b

x

b

z

Þð2Þ

Figure 1

Magnetostriction modes for hexagonal and cubic

symmetries.

766

Magnetoelastic Phenomena

where l

a,0

is the isotropic strain which does not de-

pend on the orientation of M, l

g,2

describes the te-

tragonal distortion, and l

e,2

the rhombohedral

distortion of the cubic crystal. Instead of l

a,0

, l

g,2

,

and l

e,2

, the constants l

0

¼l

a,0

, l

100

¼2l

g,2

, and

l

111

¼2l

e,2

are generally used.

1. Magnetovolume Effects

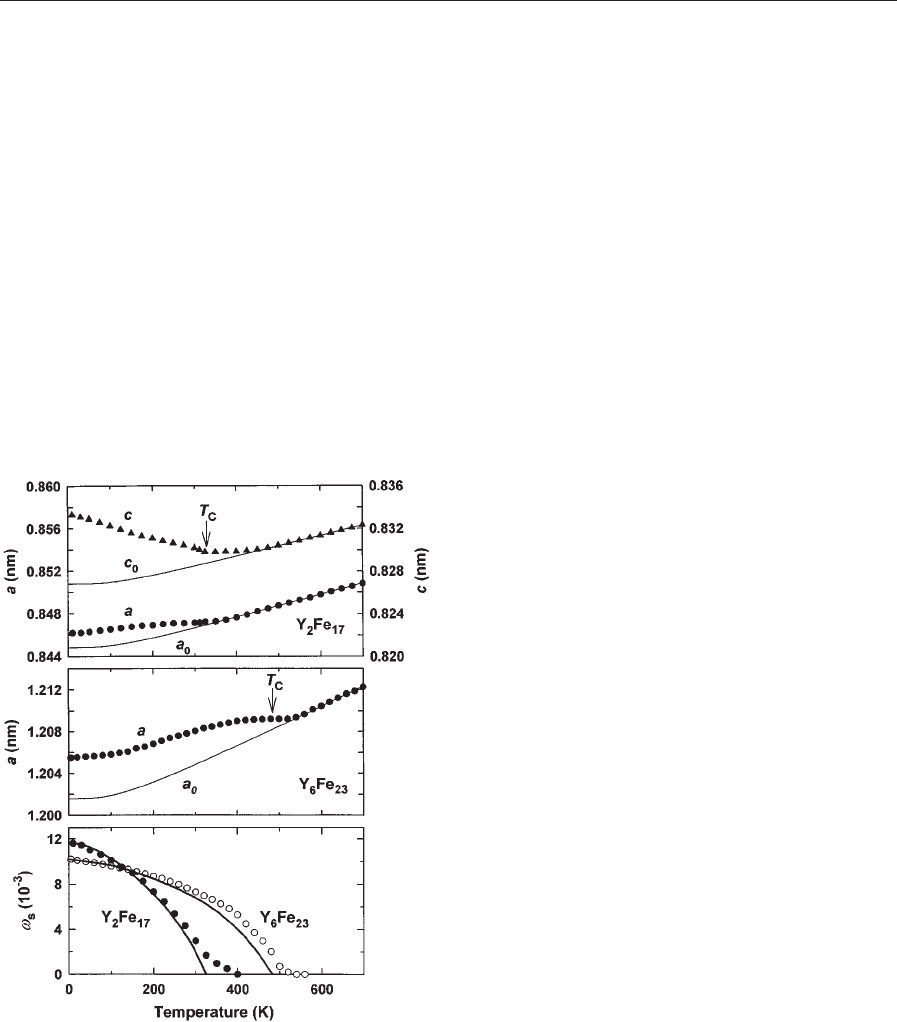

Figure 2 shows the temperature dependence of lattice

parameters of Y

2

Fe

17

(hexagonal crystal structure)

and Y

6

Fe

23

(cubic crystal structure) (Givord et al.

1971, Andreev 1995 and references therein). The

curves in Fig. 2 represent the phonon contribution to

the thermal expansion obtained by extrapolation of

the paramagnetic behavior into the ferromagnetic

range. Below the Curie temperature, T

C

, the exper-

imental curves deviate from the extrapolated ones.

The differences between the measured and the ex-

trapolated values of the respective lattice parameters

correspond to the spontaneous linear MS. Both com-

pounds have a negligible anisotropic MS compared

to a large isotropic MS. Therefore, the total values of

the basal-plane strain, l

a

, and uniaxial strain, l

c

,in

Y

2

Fe

17

correspond to the l

a;0

1

and l

a;0

2

MS constants,

respectively. In cubic Y

6

Fe

23

, the spontaneous MS is

described only by l

a,0

. Usually, the spontaneous MS

is considered in terms of a volume effect o

s

¼

2l

a;0

1

þl

a;0

2

(crystals with a unique axis) and o

s

¼3l

a,0

(cubic crystal).

The volume MS has two main origins: the volume

dependence of the magnetic moment and the volume

dependence of the exchange interactions (du Tremo-

let de Lacheisserie 1993 and references therein). The

first is important in itinerant ferromagnets, where the

3d electron states responsible for magnetism generally

form an energy band (see Itinerant Electron Systems:

Magnetism (Ferromagnetism)). The magnetization

arises as a result of splitting of sub-bands owing to

the exchange interaction (spontaneous effect) or to

application of the external magnetic field H (forced,

or field-induced effect). The 3d-band polarization

causes an increase in the kinetic energy of electrons.

This is compensated by a volume expansion. The in-

crease in kinetic energy is proportional to M

2

to a

first approximation. The corresponding volume

change can be expressed as:

o ¼ DV=V ¼ kCM

2

ð3Þ

where k is the compressibility and C is the magneto-

volume coupling constant.

This formula describes the magnetovolume effect

in itinerant ferromagnets both in zero field (sponta-

neous volume MS, o

s

, in this case M ¼M

s

, the spon-

taneous magnetization) and in magnetic field (forced

volume MS). In Fig. 2 the temperature dependence of

o

s

for Y

2

Fe

17

and Y

6

Fe

23

is compared with M

2

S

.A

good agreement with Eqn. (3) is seen for a wide tem-

perature range. However, 15–20% of low-tempera-

ture o

s

value persists at T

C

where M

s

becomes zero.

Finally, o

s

vanishes at temperatures considerably

higher than T

C

. Such behavior, typical for com-

pounds with a large magnetovolume effect, is attrib-

uted to the existence of a short-range magnetic order

in a wide temperature interval above T

C

.

The value of o

s

in itinerant ferromagnets is usually

positive and sometimes very large. As seen in Fig. 2, it

exceeds 1% in Y

2

Fe

17

and Y

6

Fe

23

. Even larger o

s

values, up to 3%, are observed in some R

2

Fe

14

B and

La(Fe,Al)

13

compounds (Andreev 1995 and referenc-

es therein). The o

s

value can be larger than the pho-

non contribution below T

C

. In such a case the total

thermal expansion coefficient becomes very small or

even negative (see Invar Materials: Phenomena). It is

observed in many compounds with low ordering tem-

peratures (o100K) owing to a relatively low phonon

contribution. Even a moderate value of o

s

(B10

3

)

is sufficient to exceed the phonon contribution and

Figure 2

Temperature dependence of lattice parameters a and c of

Y

2

Fe

17

and a of Y

6

Fe

23

. The curves are the phonon

contribution to the thermal expansion. The arrows

indicate the Curie temperature. Bottom: temperature

dependence of spontaneous volume magnetostriction o

s

;

the lines represent the o

s

(T) ¼o

s

(0)M

2

s

(T)/M

2

s

(0)

dependence.

767

Magnetoelastic Phenomena

produce the Invar-like anomaly in a narrow temper-

ature interval. In some rare cases the Invar effect over

a wide temperature interval (including room temper-

ature) can be observed. Besides the above-mentioned

iron-rich intermetallics, it occurs also in iron-rich

f.c.c. alloys. Other typical examples of systems with

large magnetovolume effects are weak itinerant ferro-

magnets (ZrZn

2

, MnSi) and some antiferromag-

netic (AF) alloys and compounds (Cr–Mn, YMn

2

)

(Nakamura 1983).

The second origin of volume MS, the volume de-

pendence of the exchange interactions, dominates in

ferromagnets with a weak volume dependence of the

magnetic moment. The isotropic MS constant is then

proportional to the magnetic Gru

¨

neisen coefficient

G ¼(d lnT

C

/d lnV):

l

a;0

BGM

2

ðH; TÞð4Þ

where M is a volume-independent magnetic moment.

The Gru

¨

neisen coefficient is usually negative and of

the order of unity for most ferromagnets, but some-

times is large and positive for weak itinerant ferro-

magnets. The absolute value of o

s

in these materials

is always much smaller than in Invar alloys. Typical

values of o

s

are 1.1 10

3

for nickel, 2.7 10

3

for iron, and þ2.6 10

3

for gadolinium (du Tremo-

let de Lacheisserie 1993).

The forced volume MS (o

f

) has the same physical

origins as the spontaneous volume MS. For moderate

magnetic fields and temperatures sufficiently lower

than T

C

, the forced volume MS is associated with the

paraprocess and o

f

is a linear function of the applied

magnetic field after technical saturation has been

achieved. The o

f

values are small for strong ferro-

magnets at low temperatures (dl

a,0

/dH ¼4.5

10

6

T

1

for pure iron at 1.5–300 K (du Tremolet de

Lacheisserie 1993)) and o

f

usually has a maximum

around T

C

. Large o

f

values at low temperatures are

characteristic of weak itinerant ferromagnets.

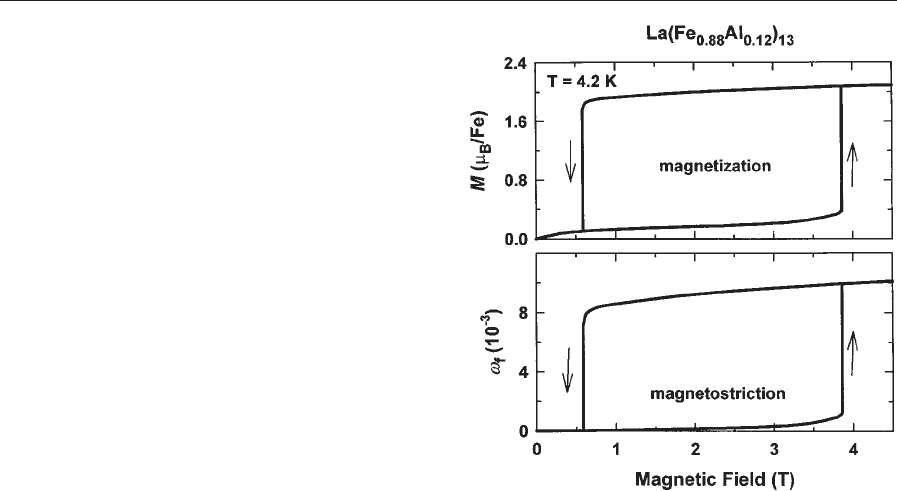

A very large o

f

(up to 2%) may be observed at

field-induced changes of magnetic structure. This oc-

curs first of all at first-order metamagnetic phase

transitions. The field-induced state is ferromagnetic,

whereas the initial state can vary. An AF–F transi-

tion with large o

f

is observed, for example, in FeRh

(Levitin and Ponomarev 1966) and La(Fe

0.88

Al

0.12

)

13

(Palstra et al. 1985). The transition from a low-mo-

ment to a high-moment state is observed in

Sc

0.25

Ti

0.75

Fe

2

(Kido et al. 1988), and from the par-

amagnetic to the F state in the YCo

2

- and LuCo

2

-

based alloys (see Metamagnetism: Itinerant Elec-

trons). Figure 3 shows the magnetization and MS

curves for a polycrystal of La(Fe

0.88

Al

0.12

)

13

at 4.2 K.

The metamagnetic transition with a wide field hys-

teresis is accompanied by positive o

f

¼1%. However,

the large o

f

is not a universal feature of a metamag-

netic transition. For example, despite the relatively

large longitudinal and transverse magnetostrictions

accompanying the metamagnetic transition in a single

crystal of UNiGa (observed when the magnetic field

is applied along the c-axis of the hexagonal struc-

ture), o

f

¼2l

a

þl

c

is negligible due to the mutual

cancellation of the linear effects (Andreev et al. 1995).

When external pressure is applied to a magnetically

ordered material, two magnetoelastic effects occur:

changes of the magnitude of magnetic moments and

of the energies of moment coupling. For details

see Magnetic Systems: External Pressure-induced

Phenomena.

2. Anisotropic MS

Whereas isotropic (volume) MS depends on the mag-

nitude of magnetic moments and the coupling be-

tween them, anisotropic MS describes the changes of

dimensions and shape of a sample depending on the

orientation of the magnetic moments. Also, the an-

isotropic MS can be spontaneous or field induced.

The thermal expansion in the magnetically ordered

range is affected both by isotropic and by anisotropic

MS. The anisotropic MS always causes a reduction of

symmetry in the cubic structure. For the hexagonal

structure a component of anisotropic MS exists, de-

scribed by the constants l

a;2

i

in Eqn. (1), which has no

influence on symmetry. Usually, the linear spontane-

ous strains l

a

and l

c

, which are combinations of

l

a;0

i

and l

a;2

i

, cannot be separated. However, in the

Figure 3

Magnetization and forced volume magnetostriction

isotherms for La(Fe

0.88

Al

0.12

)

13

at 4.2 K.

768

Magnetoelastic Phenomena

case of a spontaneous spin reorientation each contri-

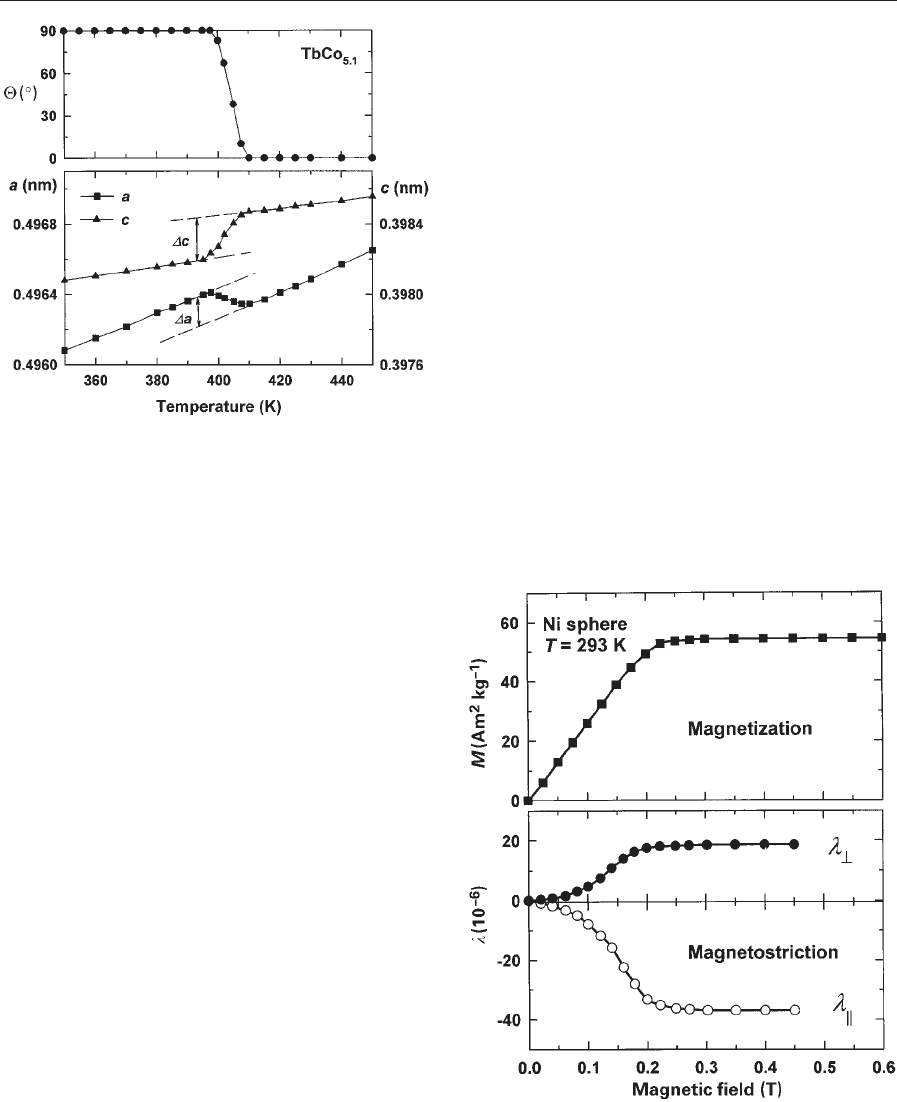

bution can be clearly distinguished. Figure 4 shows

the temperature dependence of lattice parameters of

TbCo

5.1

in the vicinity of the spin reorientation from

the basal plane (Y ¼901) to the c-axis (Y ¼0). The

corresponding steps Da/a and Dc/c are equal to

l

a;2

1

E0.3 10

3

and l

a;2

2

E0.6 10

3

, respectively.

The volume effect Do

s

¼2l

a;2

1

þl

a;2

2

is thus negligible.

For further details see the review of Andreev (1995).

The crystal symmetry is conserved at the magnetic

ordering only in the case of uniaxial magnetic aniso-

tropy (the easy magnetization direction is the c-axis

in the hexagonal, tetragonal, and rhombohedral

structures, or a principal axis in the orthorhombic

structure, or the b-axis in the monoclinic structure).

Magnetic order with any type of multiaxial aniso-

tropy (in particular, any possible anisotropy in the

cubic structure) yields reduced symmetry, which is

manifested as a spontaneous distortion. The easy

magnetization direction parallel to the /100S axis

in a cubic crystal yields a tetragonal distortion

c/a1 ¼l

a,2

¼3/2l

100

. In the case of the /111S easy

direction, the resulting rhombohedral distortion is

characterized by a change of the angle a from 901 to a

value given by cosa ¼2l

e,2

/3 ¼l

111

. The orthorhom-

bic distortion in the basal plane of hexagonal crystals

as well as the rhombohedral distortion in cubic crys-

tals of the rare earth and actinide compounds can

reach values of 10

3

–10

2

which exceeds by several

orders the corresponding values observed in conven-

tional materials based on metals of the iron group.

Note that this so-called ‘‘giant MS’’ is still rather

small from a structural viewpoint (e.g., l

111

¼10

3

corresponds to only 3.5 minutes of nonorthogonality

between the /100S axes).

If a magnetic field is applied on a ferromagnet, an

anisotropic deformation MS occurs. This effect was

discovered by Joule in 1842. Since l is an even function

of H (Eqns. (1) and (2) contain only even degrees of the

direction cosines of M), l ¼0 in the case of pure ro-

tation of 1801 domains. In a saturated (single-domain)

sample, as well as in a uniaxial multidomain sample

containing 1801 domains only, the Joule MS is caused

by a rotation of M from the easy direction towards the

field direction. The value of l gradually increases with

H and saturates above the anisotropy field H

a

.

In materials with multiaxial magnetic anisotropy

(e.g., in cubic crystals) the Joule MS is caused first

of all by a domain wall displacement leading to re-

distribution of magnetic phases with noncollinear

mutual orientation of M and to corresponding reori-

entation of spontaneous distortions. Since the do-

main walls are usually moving in relatively low H, the

anisotropic MS in samples with multiaxial anisotropy

is much more field sensitive and the MS saturates at

the field of technical saturation. Such a field depend-

ence is shown in Fig. 5 for annealed pure nickel.

Figure 4

Temperature dependence of the angle Y between the

easy magnetization direction and the c-axis and of the

lattice parameters of TbCo

5.1

in the vicinity of spin

reorientation from the basal plane (Y ¼901) to the

uniaxial anisotropy (Y ¼0).

Figure 5

Field dependence of magnetization, M, and longitudinal

(l

8

) and transverse (l

>

) magnetostriction of a nickel

polycrystal at room temperature.

769

Magnetoelastic Phenomena